Abstract

To overcome the inherent weakness of polylactic acid (PLA), used as scaffolding materials, multiple samples of Mg/PLA alloy composite materials was made by plastic injection molding. To enhance the interfacial interaction with PLA, magnesium alloy was treated with microarc oxidation (MAO) at four different frequencies, resulting in an improvement in mechanical strength and toughness. The microarc oxidation films consisted mainly of a porous MgO ceramic layer on the Mg rod. Based on the phenomenon of micro-anchoring and electrostatic interaction, a change in frequency during MAO showed considerable improvements in the ductility of the composite materials. The presence of the ceramic layer enriched the interfacial bonding between the Mg rod and outer PLA cladding, resulting in the PLA-clad Mg rod showing a higher tensile strength. In vitro degradation test was carried out in Hank’s solution for different time periods. Surface-treated Mg alloy-based composite samples displayed a lower degradation rate as compared to untreated Mg alloy samples. The surface-treated sample at a 800 Hz pulse frequency showed the best degradation resistance and mechanical properties after being immersed in Hank’s solution as compared to other samples. Mg-reinforced PLA composite rods are promising candidates for orthopedic implants.

1. Introduction

Recently, a surge in demand for biodegradable implants has created a huge interest in fast production of quality bone repair biomaterials.1 Cobalt-chromium alloys, titanium alloys, and stainless steels are some of the candidates employed for internal bone repair, leading to their higher strength.2 Moreover, temporary implantation, which does not limit progressive bone growth and prevents stress shielding, is suggested for patients less than 40 years old. However, a second surgery is often required for its retention and removal.3 Biodegradable and biocompatible materials are suitable for helping in the recovery of tissues damaged without transient loss of mechanical support. These materials eventually dissolve in the body after a certain period of time without giving the need for a second surgery. Various forms of biodegradable polymers have been utilized for such purposes, which include polyglycolic acid (PGA), poly(α-hydroxy acid)s, polydioxanone (PDS),4 and polylactic acid (PLA).5 Polylactic acid plays an important role in bioabsorbable or biocompatible materials and medical applications due to hydrolyzing its essential α-hydroxy acid on the localized tissue having no carcinogenic effects. Furthermore, polylactic acid has several benefits, i.e., derived from natural resources and better thermal processing capability than other biopolymers. Despite its useful features, polylactic acid has some drawbacks to be a complete substitute to improve load-bearing bone ability due to its poor toughness. Various methods have been explored to improve the mechanical properties of polylactic acid. In a study by Weiler et al., pure PLA rods fabricated by the extrusion process exhibited an enhanced bending strength of 200 MPa and modulus of 9 GPa as compared to conventional injection molding showing a bending strength of 140 MPa and modulus of 5 GPa.6

Currently, permanent and long-lasting metallic implants due to their influential high strength and corrosion resistance are used to fix the bone damage and fracture. They have been widely used as the load-bearing implants for bone healing and repair of damaged tissues.7 Despite the advantages of permanent implantation, they have two key problems. First, they cause stress shielding leading to the reduction of load borne by the bone by the implant results in osteopenia.8 This effect is produced by a mechanical mismatch in elastic modulus between the surrounding bone (10–45 GPa) and implant (100–200 GPa).9 Second, when the tissues heal sufficiently for a certain period of time, the metallic implant must be taken out from the body by using a secondary surgical intervention, which causes an increase in cost to the health care system and emotional stress to the patient. Several studies have been reported that focus on adding different filler materials as reinforcements to PLA to enhance mechanical properties. These include bioactive glass, chitosan, magnesium alloy rod, and titania nanoparticles.10−14

Incomplete dissolution of these materials in the body can leave a lasting effect in the living tissue; therefore, fully degradable bio-materials are required. Amongst the fully biodegradable implants, Mg-based implants have become an incipient material having high specific strength and low density notably in biomedical application due to their exceptional biocompatibility for the repairing of bone and coronary arterial stents.15−17 Magnesium is necessary for human metabolism and is the fourth most abundant cation in the human body, around 25 g of Mg stored in the human body and about half of it contained in the bone tissue. Furthermore, Mg is a cofactor for various enzymes, which stabilizes the structure of RNA and DNA. Gu et al.18,19 found that the corrosion product layer formed on the surface of AZ31 Mg alloys during immersion in the simulated body fluid results in an improvement in the alloy’s corrosion resistance, which basically depends on the thickness of the compact layer. However, chemically aggressive environments that include chloride ions can accelerate the degradation rate, fast deteriorating the mechanical properties of Mg alloys.20−24 Another issue arises with the formation of hydroxide ions and release of hydrogen during Mg degradation. This leads to tissue damage in the vicinity of the implant while also decreasing the implant’s mechanical strength due to rapid gas evolution and an increase in pH to the alkaline region.25,26 Surface treatments have shown to decrease degradation rates in the case of Mg alloys.27 A common surface modification includes laser surface alloying,28 conversion coatings,29 alkaline treatment,30 microarc oxidation,31 and sol–gel coating.32 From the listed possible treatments, microarc oxidation presents a more convenient and economical route to enhanced surface behavior.33−38 The microarc oxidation (MAO) technique of Mg alloys has been subject to extensive research in the past few years. Wilke et al.39 reported that MAO-coated AZ31 Mg alloys considerably enrich the corrosion resistance in the simulated body fluid. Sankara Narayanan et al. found that MAO treatment could improve the bonding strength of the Mg alloy substrate.40−44 Therefore, microarc oxidation is an appropriate technique to achieve corrosion-resistant bio-ceramic coatings. According to the research reported, the main focus has been toward an improvement in degradation rate. Porosity in the outer structure of the alloy, obtained through MAO, improves the mechanical interlocking while also increasing the bonding area, which in turn improves stress distribution at the surface interface of the joints. Therefore, the microstructure of the porous layer may directly influence the adhesion property and load-bearing capacity of the Mg rod. The MAO layers depend on the electrolyte concentration and experimental factors such as voltage applied, current density, and time. NaCl solution has been used to reveal the influence of oxidation time on degradation resistance of MAO coatings on Mg alloys.45,46 Hank’s solution is used to study the effect of coated Mg alloys in biological conditions. However, the influence of oxidation time on MAO-coated AZ31 alloys in Hank’s solution has not been reported. Considering the adaptability of the MAO process in a chemical solution and topographic amendments of the implant surface and its significant positive role in bone regeneration, we hypothesized that the MAO may be a favorable candidate in the fabrication of the necessary designs as mentioned above. In the present study, our research is focused on the in vitro degradation and surface treatment of the Mg alloy rod-reinforced PLA composites. The study tried to explain the external effect of the Mg rod treated with MAO at different frequencies and the influence on the mechanical properties of PLA composites, morphology change, porosity, and degradation resistance of Mg/PLA composites, which help to apprehend the substantial effects of the Mg rod on the degradation and biocompatibility of the PLA matrix.

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Materials Preparation

Industrial grade Ingeo 3251D polylactic acid (Shenzhen Esun Industrial Co., Ltd., China) was purchased (density: 1.24 g/cm3, molecular weight: 60,000 g/mol, and melt flow index: 160 °C) and was reinforced with AZ31 rod (diameter: 2.44 mm, and height: 60 mm; elemental composition: 96% Mg, 3% Al, and 1% Zn in wt %).

2.2. Coating Preparation

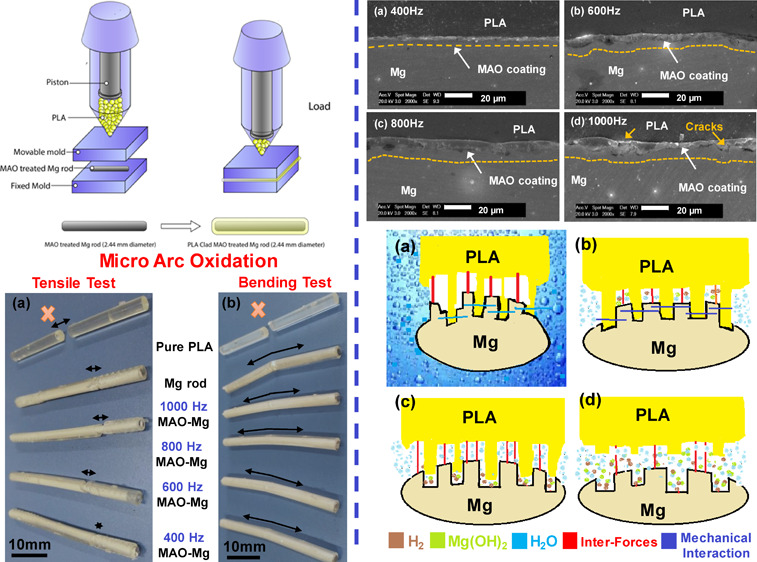

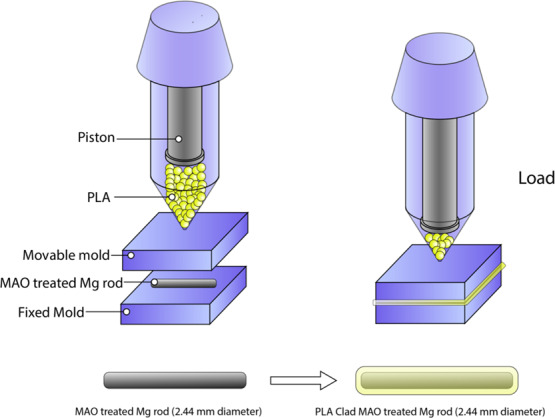

Prior to the MAO treatment, AZ31Mg rods were ground to 1000 grit size with SiC sandpaper for higher surface roughness, then they were washed with ethanol in an ultrasonic cleaner for 20 min. Microarc oxidation treatments were performed in the solution containing Na2SiO3 (13 g/L), Na3PO4 (5 g/L), and NaOH (2.5 g/L). Potential was applied at frequencies of 400, 600, 800, and 1000 Hz with the same duty cycle as shown in Table 1. Macroscopic pictures of the pure Mg rod, pure PLA, and MAO-treated surface were taken. As can be seen in Figure 1a, the Mg rod is surface treated at 400, 600, 800, and 1000 Hz. The coating thickness and surface roughness can be seen to increase as the pulse frequency increases.

Table 1. Microarc Oxidation Process Parameters.

| material | pulse frequency (Hz) | applied voltage (V) |

|---|---|---|

| Mg rod (2.44 mm) | 400 | 280 |

| Mg rod (2.44 mm) | 600 | 280 |

| Mg rod (2.44 mm) | 800 | 280 |

| Mg rod (2.44 mm) | 1000 | 280 |

Figure 1.

Demonstration of the preparation process of PLA-clad MAO-treated Mg composite rods.

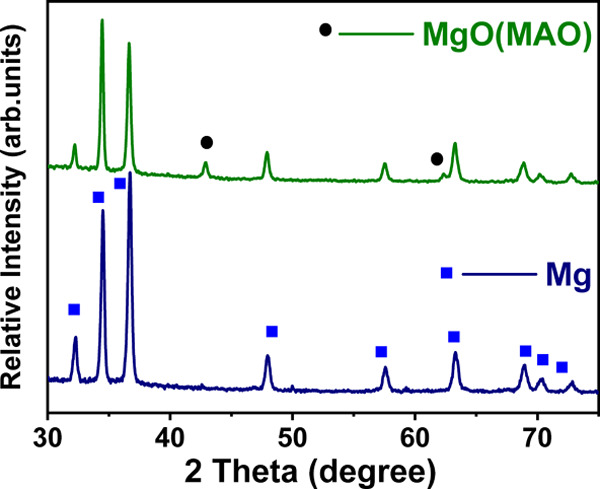

2.3. Fabrication of Composites by Injection Molding

Mg rods were used to fabricate composite rods by plastic injection molding (PIM) as shown in Figure 1b. The untreated Mg rods and those treated with microarc oxidation were inserted in the die prior to the introduction of PLA pellets into the hopper. Composite samples were finally cooled to room temperature before being taken out of the die. Pure PLA samples were also made by plastic injection molding. Schematic demonstration of PLA-clad MAO-treated Mg-composite rods preparation is illustrated in Figure 1.

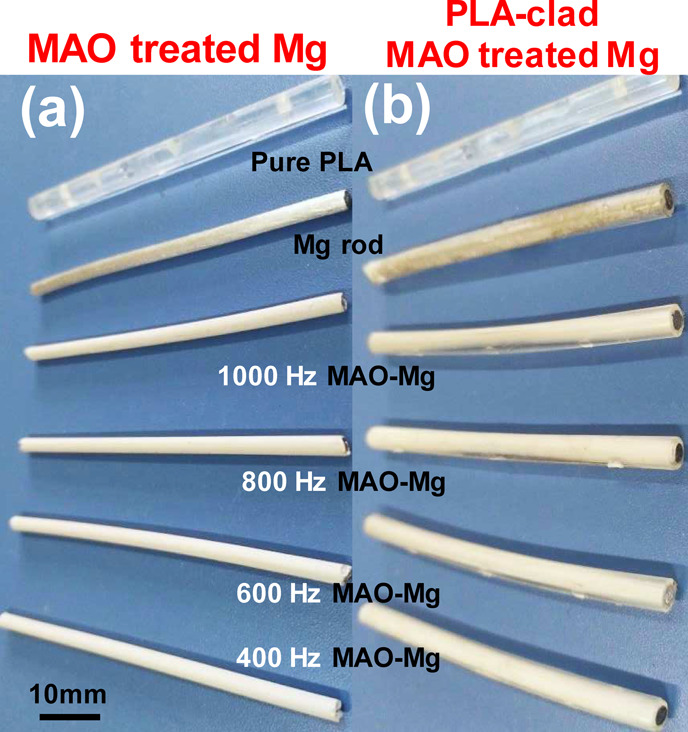

2.4. Coating Characterization

Surface morphologies were carried out by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The cross-sectional SEM micrographs were used to calculate the sample thickness. The phase structure was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (D8-Discover, Bruker) using the following conditions: Cu Kα radiation (wavelength λ = 0.154 nm) in the range of 5–70°, acceleration voltage of 40 kV, current of 30 m/A, scanning step of 0.02 (C°)/step, and scanning speed of 2 s/step.

2.5. Mechanical Properties

Three-point bend and tensile tests using MTS’s universal testing machine (UTM, model CMT4503) were carried out at room temperature with a strain rate of 1 mm/min. For the tensile test, the PLA-clad Mg rod was used with a diameter of 4 mm and height 40 mm. For the bend test, the PLA-clad Mg rod was used with a diameter of 4 mm and height 7 mm. In order to analyze the degradation kinetics, samples were immersed in Hank’s solution. The amount of H2 released was measured with immersion time. To measure the H2 release in Hank’s solution, a 20:1 solution of media volume (mL) to specimen surface (cm2) was used. An inverted glass funnel was used with a burette to capture H2. The levels of burettes were measured three times a day in relation to the area of the sample.

2.6. In Vitro Immersion Testing

A PE bottle containing 15 mL of Hank’s solution was made to study the degradation rate and corrosion resistance. The sample was put in the bottle and placed in the thermostat oscillating slot at (37.5 ± 0.5) °C. The bare surfaces of PLA-clad rods were inserted into the epoxy resin on both sides. ISO 10993-12 was followed for in vitro tests.34 Treated and untreated rods were soaked in the solution for 3, 7, 14, and 30 days. After that, treated and untreated rods were washed with distilled water and then dried in air. Pre- and post-immersion cross-sectional and surface microstructures and morphologies were characterized by SEM.

2.7. Weight Loss Test

The weight loss method is usually considered to be the most basic and reliable method to analyze the corrosion degree to study the change in composites during the soaking process. The coated and uncoated specimen was soaked for different days and was measured at a different time period to calculate the corrosion rate of weight loss. The weight loss rate formula is presented as follows:

where m is the mass of the samples after immersion (g), ω is the weight loss rate (%) and m0 is the initial mass of the sample before soaking (g).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure and Surface Morphology

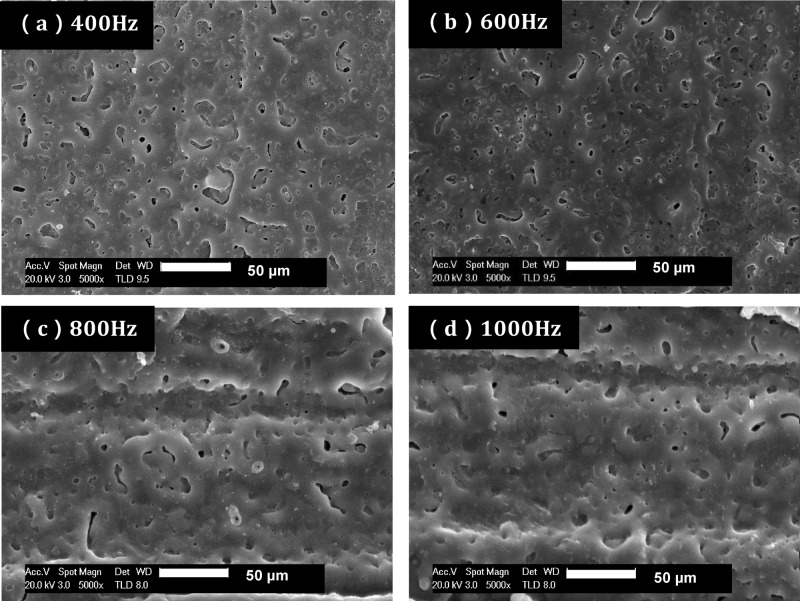

Macroscopic photos of PLA-clad MAO-treated Mg rods, PLA-clad Mg rods, and pure PLA rods are shown in Figure 2. The surface morphology for the coatings produced at different frequencies as observed by SEM. As seen in Figure 3a, at a low frequency of 400 Hz, the oxidation coatings showed round shrinkage pores in the center of some dense crater-like areas. A developed melt network was also formed at 400 Hz. As seen in Figure 3b, at a slightly higher frequency of 600 Hz, the pore size can be observed to increase a little. Some of the pores can be seen to have merged, leading to large elliptical shapes. At a frequency of 800 Hz (Figure 3c), the trend for an increase in pore size continued. The pores have now changed from being more round in shape to more elliptical. This is because the fraction of smaller, round pores may have eliminated or agglomerated, leading to a larger number of large, elliptical pores. Finally, as shown in Figure 3d, a loose grained, larger pore morphology can be observed at 1000 Hz. The pore size increased with an increase in arc frequencies. Higher frequencies during microarc oxidation seem to have merged small pores, resulting into larger ones that can be classified as small craters present on the surface. These larger pores extend hardly up to a micron beneath the surface of Mg.

Figure 2.

Photographs of (a) prepared samples at various surface-treated MAO process, Mg sample, and pure PLA sample and (b) PLA-clad MAO-treated Mg rods, PLA-clad Mg rod, and pure PLA rod.

Figure 3.

Surface morphology of MAO coatings produced at various pulse frequencies: (a) 400 Hz, (b) 600 Hz, (c) 800 Hz, and (d) 1000 Hz.

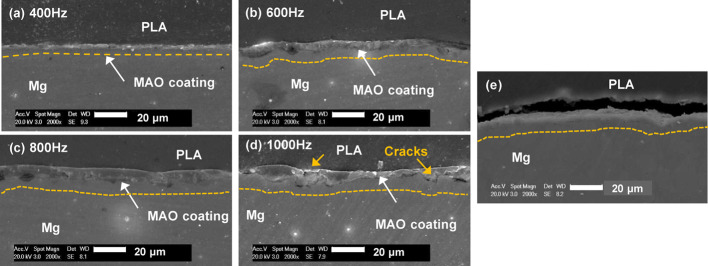

In Figure 4, the cross-sectional morphologies of the MAO coatings treated at various pulse frequency times are illustrated. The thickness (approximately 5 μm at 400 Hz) increases with pulse frequency till 800 Hz (10 μm). A 400 Hz frequency showed the thinnest coating as in Figure 4a. A higher coating frequency of 600 Hz results in a slightly thicker MAO coating. The surface of the magnesium alloy has good wetting with PLA. Good wetting can effectively avoid the formation of voids at the interface due to poor infiltration, thus avoiding cracks caused by stress concentration. Figure 4c shows the sample with the thickest layer having a relatively smooth and uniform thickness, and this sample was coated at 800 Hz. The average coating thickness was measured to be around 10 μm. However, at 1000 Hz, the uniformity in coating thickness changes and the surface becomes rough. Some areas can be seen to have a coating thicker than 10 μm, while other surfaces have a coating thickness of 5 μm or even lesser. This results in the formation of more local voids caused by portions of the disintegrated surface. At higher pulse frequencies, there is a high temperature and pressure generated by a longer discharge length, causing the coating to undergo local melting and deterioration as shown in Figure 4d. By comparison, the untreated surface of a PLA-clad Mg rod shows an observable gap between Mg and PLA (Figure 4e), which arises due to a lower wettability of Mg with PLA. Mechanical stresses, such as tensile and shear, will cause material failure at low values due to a relatively weak interfacial bonding strength.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of the cross section of composites rod: (a) PLA-clad MAO-treated Mg rod at 400 Hz, (b) PLA-clad MAO-treated Mg rod at 600 Hz, (c) PLA-clad MAO-treated Mg rod at 800 Hz, (d) PLA-clad MAO-treated Mg rod at 1000 Hz, and (e) PLA-clad Mg rod.

The interfacial strength between the metal and the polymer is based on the morphology and chemical composition of the surfaces in contact. Many studies have shown that oxidation of metal surfaces can significantly improve the binding energy between the metal and the polymer.47 It is generally believed that this increase in interface binding is mainly due to the intercalation of O– and the H+ ions of the polymer. In addition, the O– and Mg+ ions in the film forming MgO can also significantly improve the interface binding.

After the microarc oxidation process on the Mg rod, a micro-porous structure is uniformly distributed on the oxide film as shown in Figure 3. During fabrication of composite rods, polylactic acid enters into these pores, resulting in the mechanical locking effect, thereby improving the adhesion between polylactic acid and magnesium alloy. In addition, the presence of O atoms in the film also can cause intermolecular forces between the two, which are the main factors in the improvement of the interfacial bonding strength.45 Thus, the interfacial forces between the microarc oxidized magnesium alloy and polylactic acid are provided by intermolecular forces and mechanical locking effect. Figure 5 shows the results of XRD patterns of the MgO-coated and non-coated Mg rods. The observed peaks in the XRD of coated rods were known as MgO, signifying the formation of MgO ceramic porous coating due to AO treatment.

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the surface of pure and MAO-treated Mg rod.

3.2. Mechanical Properties

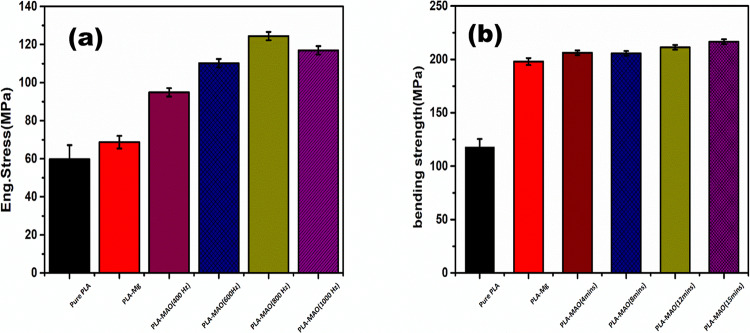

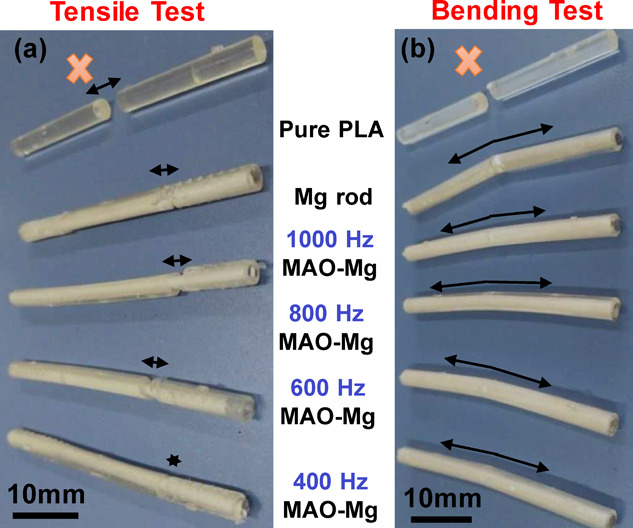

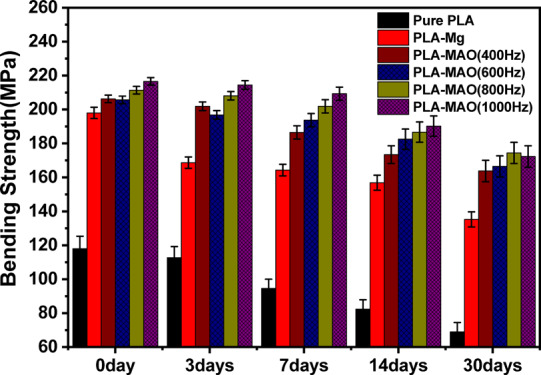

Tensile and bend tests of PLA and Mg were performed to determine the binding strength. The tensile strength of pure PLA and composite rods is shown in Figure 6a. The tensile strength of the pure PLA sample was measured to be ∼60 MPa. The composite rod showed that the external PLA layer fractured before the internal Mg rod, leading to failure of the material, as shown in Figure 7a. The ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of the Mg-PLA rod was 69 and Mg-MAO-PLA rod at 400, 600, 800, and 1000 Hz corresponds to the bars, which show values of 95, 110, 124, and 117 MPa, respectively. The strength of the composite rod showed a significant increase in strength as compared to pure PLA. Furthermore, the MAO-treated Mg rod showed higher values of UTS as compared to the untreated rod. This implies that the intermediate MgO layer plays a crucial part in the improvement of physical properties as it enhances the interfacial adhesion between the PLA and Mg interfaces. The tensile strength of the composite samples increases with an increase in MAO frequency, reaching a maximum for samples treated at 800 Hz. This effect can be attributed directly to the thickness and morphology of the MgO film, as discussed previously in Figure 4. During the bend test as shown in Figure 6b, the pure PLA rod showed an ultimate strength of ∼118 MPa. However, only the outer PLA fractured for the composite rod, as shown in Figure 7b. The ultimate bending strength values of the Mg-PLA rod and Mg-MAO-PLA rod at 400, 600, 800, and 1000 Hz were around 198 and 206, 206, 211, and 216 MPa, respectively. However, for the bend test, a significant increase in the ultimate strength values for MAO-treated samples is not seen. It can be inferred that the Mg-PLA adhesion makes a significant role in enhancing the tensile strength of the composites as compared to the bend strength. Figure 4 shows the results of XRD patterns of the MgO-coated and non-coated Mg rods. The observed peaks in the XRD of coated rods were known as MgO, signifying the formation of MgO ceramic porous coating due to AO treatment.

Figure 6.

Tensile and bending strength of composite rods and pure PLA sample.

Figure 7.

(a) Post-tensile and (b) bending test pictures of pure PLA and composite rods.

3.3. Post-immersion in Hank’s Solution

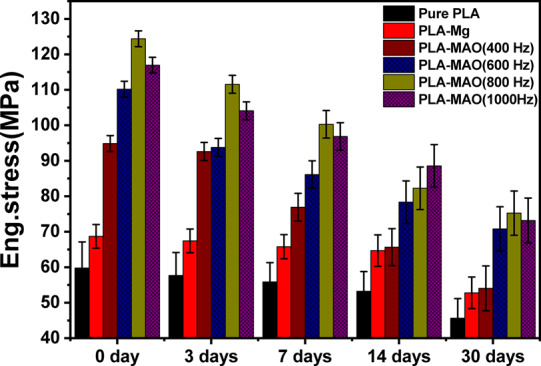

3.3.1. Tensile Strength

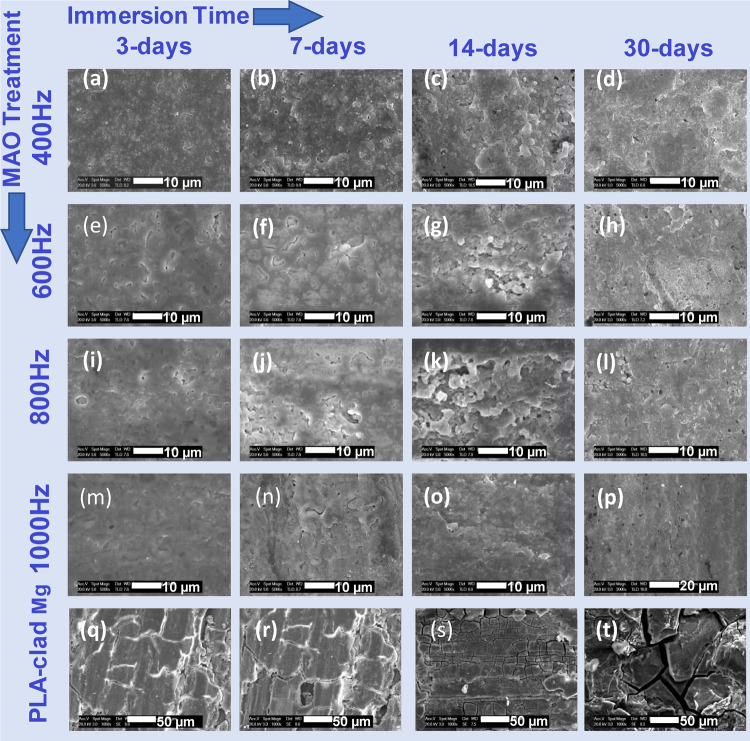

To evaluate the mechanical stability of six different samples when soaked in Hank’s solution, the tensile and bend tests were carried out after 3, 7, 14, and 30 days of immersion. Figure 8 shows the tensile test results as a function of number of days immersed in solution. An overall decrease in the tensile strength values with increasing immersion time can be observed. The tensile strength values of 400 Hz MAO-treated Mg composite rods become equal to Mg-PLA when measured on the 14th and 30th day. With prolonging the immersion time, the micro-anchoring mechanism between the MgO and PLA layer weakens and may disappear entirely as shown in Figure 11a–d, eventually resulting in a drastic decrease in their binding strength. Therefore, the UTS of the pure Mg-MAO-PLA rod treated at 400 Hz is eventually reduced from ∼95 to 55 MPa after 14 days of immersion. The UTS of the pure Mg-MAO-PLA rod treated at 600, 800, and 1000 Hz decreases relatively slower, from ∼111 to 71 MPa, ∼125 to 76 MPa, and ∼117 to 74 MPa after 30 days, respectively. Immersion also leads to severe cracking and roughening of the surface of PLA-clad Mg samples as seen in Figure 11q–t, implying that corrosion decreases the binding capacity between the Mg/PLA interface. The tensile strength of pure PLA-clad Mg samples decreases from ∼69 to 53 MPa after 30 days. The tensile strength reduction is gradual for pure PLA as the degradation for it is slower in Hank’s solution. It still has the lowest UTS throughout the immersion period due to its low mechanical properties at only ∼46 MPa after immersion for 30 days.

Figure 8.

Ultimate strength of five kinds of composite rods and pure PLA as a function of immersion time until 30 days.

Figure 11.

Surface morphologies of the composite rods as a function of coating type and immersion time.

3.3.2. Bend Strength

Figure 9 shows the plot between bend strength verses immersion time. In the presence of the MgO layer made by the MAO-treated Mg substrate, the bend strength was found to be higher as compared to non-treated composite samples and pure PLA rod post-immersion. As shown in Figure 11b–p, it shows that the porous MAO process smoothens with increased immersion time, while the micro-anchoring between the interface of PLA and MgO degrades until it disappears completely, leading to a very high reduction in the interfacial strength. The ultimate strengths of composite rods (treated and non-treated) display a slower reduction in bend strength even after 30 days of immersion as compared to tensile strength reduction. However, the decrease in bend strength of pure PLA is more significant, from ∼120 to ∼70 MPa after 30 days. When comparing MAO-treated and non-treated samples, strength retention in the treated samples was observed to be higher than that in non-treated samples. Hence, MAO treatment shows better strength retention properties. Furthermore, the MAO coating prevents pitting corrosion on the Mg rod during immersion (Figure 11h–p).

Figure 9.

Ultimate bending strength of five kinds of composite rods and pure PLA rod as a function of immersion time until 30 days.

3.4. Immersion Degradation Behavior

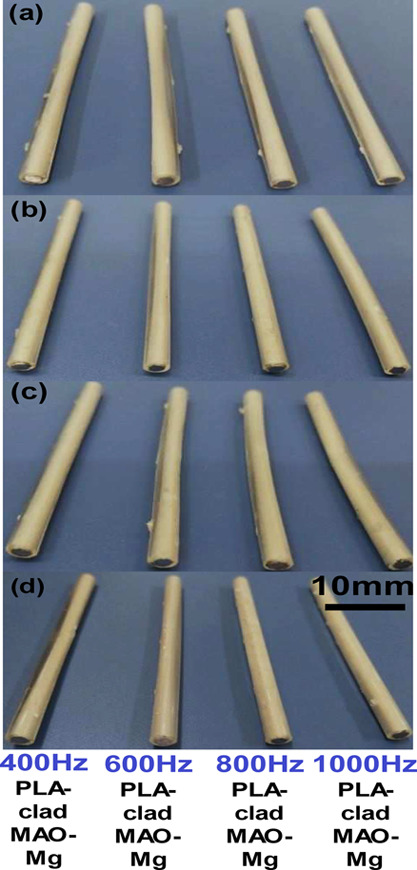

3.4.1. Immersion Degradation Morphologies

Hank’s solution was performed to test the long-term degradation treatment of coated Mg rods. Figure 10a–d shows pictures of the treated sample at different frequencies at different immersion times. Degradation of samples was directly proportional to immersion time; however, it was much slower in all the PLA-clad composite rods. However, as shown in Figure 10, all samples look the same when seen from the naked eye, but when the composites rods were exposed to dichloromethane solution, the PLA claddings were separated from the Mg rod surface.

Figure 10.

Composite rods after immersion in Hank’s solution for (a) 3 days, (b) 7 days, (c) 14 days, and (d) 30 days.

The surface morphologies as revealed by SEM are shown in Figure 11, where the column leads to immersed treated samples at different pulse frequencies and the untreated samples stripped of PLA, respectively; the row shows sample surfaces as a function of immersion time. From Figure 11, after just 3 days of immersion of the untreated sample, cracks begin to show up on the Mg surface. Increased immersion time results in higher degradation and shows more cracks, fractures, holes, and pits. On day 7, the composite sample surfaces show numerous small pinholes. Pits and corrosion products are formed gradually. Overall, the 1000 Hz samples, as shown in Figure 11m–p, display a relatively uniform and smooth surface with little pitting, endowing the Mg alloy rod with greatly enhanced resistance to corrosion.

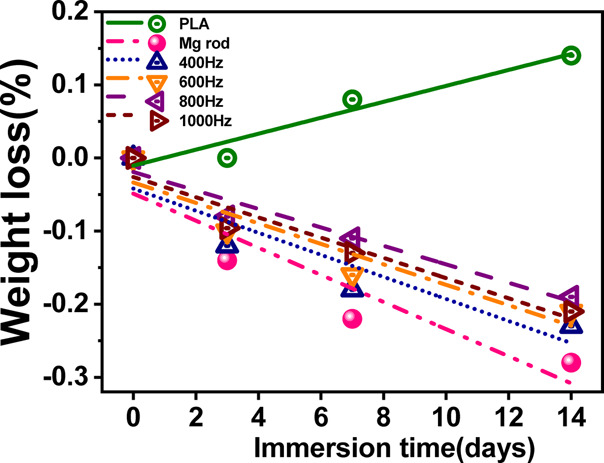

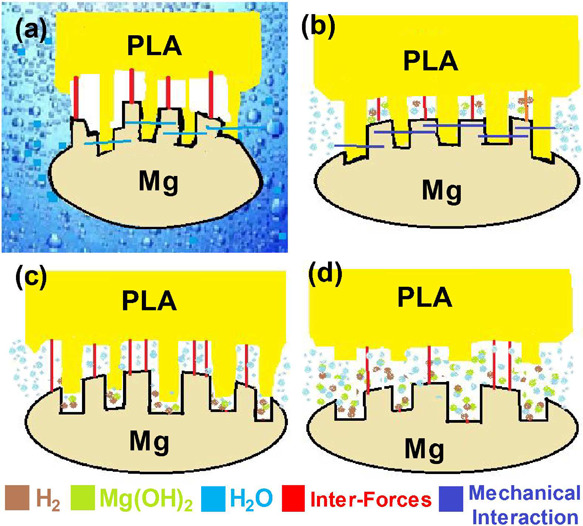

3.4.2. Weight Loss Test

Figure 12 shows the mass variation of the four composites and pure PLA after 3, 7, and 14 days of immersion in Hank’s solution. For pure polylactic acid (PLA), the weight decreased during the degradation process, but the weight change was little, and the weight loss rate was only 0.14% when soaked for a total of 14 days. The degradation and corrosion behavior of the composites prepared with treated and untreated magnesium alloy was also observed. The schematic diagram of the degradation process of PLA/MAO/Mg is shown in Figure 13. When the etching solution through the PLA enters the interface between the MgO and PLA (Figure 13b), the solution preferentially enters the pore film and start to dissolve the film from the pores (Figure 13c). Due to the prolongation of soaking time, the PLA at the pores is degraded and destroyed, and the corrosion products of Mg(OH)2 accumulate at the pores, due to which the pore becomes clogged by the corrosion product, causing the pore diameter to expand (Figure 13d). Finally, the mechanical locking between the PLA and layer is weakened, resulting in the decrease in the mechanical properties and interfacial bonding strength of the composite material. In the whole process of failure, the interface adhesion plays a significant role, and there is no serious corrosion of Mg alloys.

Figure 12.

Mg loss as a function of immersion time in Hank’s solution.

Figure 13.

Schematic illustration of the degradation mechanism in four different stages.

4. Conclusions

In this study, plastic injection molding was utilized to make PLA-clad Mg composite rods for bone fracture fixation applications. The following conclusions can be drawn from this research:

-

1.

Microarc oxidation films with different morphologies were prepared at different frequencies. It was seen that a higher frequency resulted in increased film porosity.

-

2.

The microarc oxidation films consisted mainly of a porous MgO ceramic layer on the Mg rod. The presence of the ceramic layer enriched the interfacial bonding between the Mg rod and outer PLA cladding, resulting in the PLA-clad Mg rod showing a higher tensile strength and degradation resistance in Hank’s solution as compared to the uncoated PLA-clad Mg rod.

-

3.

It was found that Mg samples, surface treated at a 800 Hz pulse frequency, showed the best degradation resistance and mechanical properties after being immersed in Hank’s solution as compared to other samples.

-

4.

An overall reduction in strength of the samples was perceived after immersion in Hank’s solution. However, PLA-clad Mg samples had retained their strength more as compared to untreated samples.

-

5.

Non-treated PLA-clad Mg samples showed the highest weight gain after immersing in Hank’s solution as compared to other treated PLA-clad Mg composites.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Higher Education Commission/Sector H-9/Islamabad-Pakistan (no. 21-2101/SRGP/R&D/HEC/2018) research project under SRGP.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Iaquinta M. R.; Mazzoni E.; Manfrini M.; D’Agostino A.; Trevisiol L.; Nocini R.; Trombelli L.; Barbanti-Brodano G.; Martini F.; Tognon M. Innovative Biomaterials for Bone Regrowth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 618. 10.3390/ijms20030618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliaz N. Corrosion of Metallic Biomaterials: A Review. Materials 2019, 12, 407. 10.3390/ma12030407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu B.; Karau A.; Wood A.; Dadsetan M.; Liedtke H.; DeWitt T.. Bioresorbable Materials for Orthopedic Applications(Lactide and Glycolide Based). In Orthopedic Biomaterials; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp 287–344, 10.1007/978-3-319-89542-0_13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baji A.; Mai Y.-W.. Polymer Nanofiber Composites. In Nanofiber Composites for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: 2017; pp 55–78, 10.1016/B978-0-08-100173-8.00003-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Ortiz O.; Goyal R.; Kohn J.. Biodegradable Polymers. In Principles of Tissue Engineering; Elsevier: 2014; pp 441–473, 10.1016/B978-0-12-398358-9.00023-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler W.; Gogolewski S. Enhancement of the Mechanical Properties of Polylactides by Solid-State Extrusion. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 529–535. 10.1016/0142-9612(96)82728-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi F.; Lang N. P.; De Santis E.; Morelli F.; Favero G.; Botticelli D. Bone-healing pattern at the surface of titanium implants: an experimental study in the dog. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2014, 25, 124–131. 10.1111/clr.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinomi M.; Nakai M. Titanium-based biomaterials for preventing stress shielding between implant devices and bone. Int. J. Biomater. 2011, 2011, 836587. 10.1155/2011/836587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger M. P.; Pietak A. M.; Huadmai J.; Dias G. Magnesium and its alloys as orthopedic biomaterials: a review. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 1728–1734. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä T.; Niiranen H.; Kellomäki M. Self-Reinforced Composites of Bioabsorbable Polymer and Bioactive Glass with Different Bioactive Glass Contents. Part II: In Vitro Degradation. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 156–164. 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F.; Li Q. F.; Gu B.; Liu K.; Shen G. X. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of a Biodegradable Chitosan-PLA Composite Peripheral Nerve Guide Conduit Material. Microsurgery 2008, 28, 471–479. 10.1002/micr.20514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W.; Yang F.; Seyednejad H.; Chen Z.; Hennink W. E.; Anderson J. M.; van den Beucken J. J. J. P.; Jansen J. A. Biocompatibility and Degradation Characteristics of PLGA-Based Electrospun Nanofibrous Scaffolds with Nanoapatite Incorporation. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6604–6614. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt M. S.; Bai J.; Wan X.; Chu C.; Xue F.; Ding H.; Zhou G. Mechanical and Degradation Properties of Biodegradable Mg Strengthened Poly-Lactic Acid Composite through Plastic Injection Molding. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 70, 141–147. 10.1016/j.msec.2016.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. B.; Birbilis N.; Abbott T. B. Review of Corrosion-Resistant Conversion Coatings for Magnesium and Its Alloys. Corrosion 2011, 67, 035005-1–035005-16. 10.5006/1.3563639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song G.-L.Corrosion Behavior and Prevention Strategies for Magnesium (Mg) Alloys. In Corrosion Prevention of Magnesium Alloys; Elsevier: 2013; pp 3–37, 10.1533/9780857098962.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R.-G.; Zhang S.; Bu J.-F.; Lin C.-J.; Song G.-L. Recent Progress in Corrosion Protection of Magnesium Alloys by Organic Coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2012, 73, 129–141. 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2011.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gnedenkov A. S.; Sinebryukhov S. L.; Mashtalyar D. V.; Gnedenkov S. V. Features of the Corrosion Processes Development at the Magnesium Alloys Surface. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 225, 112–118. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2013.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y.; Bandopadhyay S.; Chen C.-f.; Ning C.; Guo Y. Long-term corrosion inhibition mechanism of microarc oxidation coated AZ31 Mg alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Des. 2013, 46, 66–75. 10.1016/j.matdes.2012.09.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y.; Chen C.-f.; Bandopadhyay S.; Ning C.; Zhang Y.; Guo Y. Corrosion mechanism and model of pulsed DC microarc oxidation treated AZ31 alloy in simulated body fluid. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 6116–6126. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi S.; Kuwabara K.; Fukuta Y.; Kubota K.; Matsubara E. Formation of Self-Repairing Anodized Film on ACM522 Magnesium Alloy by Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation. Corros. Sci. 2013, 73, 188–195. 10.1016/j.corsci.2013.03.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X.-j.; Liu C.-h.; Yang R.-s.; Fu Q.-s.; Lin X.-z.; Gong M. Duplex-Layered Manganese Phosphate Conversion Coating on AZ31 Mg Alloy and Its Initial Formation Mechanism. Corros. Sci. 2013, 76, 474–485. 10.1016/j.corsci.2013.07.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witte F. The History of Biodegradable Magnesium Implants: A Review. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1680–1692. 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paital S. R.; Dahotre N. B. Calcium Phosphate Coatings for Bio-Implant Applications: Materials, Performance Factors, and Methodologies. Mater. Sci. Eng., R 2009, 66, 1–70. 10.1016/j.mser.2009.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.; He Y.; Tao H.; Zhang Y.; Jiang Y.; Zhang X.; Zhang S. Biocompatibility of Magnesium-Zinc Alloy in Biodegradable Orthopedic Implants. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 10.3892/ijmm.2011.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealy M. P.; Guo Y. B. Fabrication and Characterization of Surface Texture for Bone Ingrowth by Sequential Laser Peening Biodegradable Orthopedic Magnesium-Calcium Implants. J. Med. Devices 2011, 5, 011003 10.1115/1.4003117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; Wang G. Preparation and Corrosion Resistance of Cerium Conversion Coatings on AZ91D Magnesium Alloy by a Cathodic Electrochemical Treatment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 254, 42–48. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2014.05.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X. N.; Zheng W.; Cheng Y.; Zheng Y. F. A Study on Alkaline Heat Treated Mg–Ca Alloy for the Control of the Biocorrosion Rate. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 2790–2799. 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C. L.; Han X.; Bai J.; Xue F.; Chu P. K. Fabrication and Degradation Behavior of Micro-Arc Oxidized Biomedical Magnesium Alloy Wires. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 213, 307–312. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2012.10.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojaee R.; Fathi M.; Raeissi K. Controlling the Degradation Rate of AZ91 Magnesium Alloy via Sol–Gel Derived Nanostructured Hydroxyapatite Coating. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 3817–3825. 10.1016/j.msec.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P.; Ng W. F.; Wong M. H.; Cheng F. T. Improvement of Corrosion Resistance of Pure Magnesium in Hanks’ Solution by Microarc Oxidation with Sol–Gel TiO2 Sealing. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 469, 286–292. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.01.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng R.; Kainer K. U.; Blawert C.; Dietzel W. Corrosion of an Extruded Magnesium Alloy ZK60 Component—The Role of Microstructural Features. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 4462–4469. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.01.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laleh M.; Rouhaghdam A. S.; Shahrabi T.; Shanghi A. Effect of Alumina Sol Addition to Micro-Arc Oxidation Electrolyte on the Properties of MAO Coatings Formed on Magnesium Alloy AZ91D. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 496, 548–552. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.02.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Candan S.; Unal M.; Koc E.; Turen Y.; Candan E. Effects of Titanium Addition on Mechanical and Corrosion Behaviours of AZ91 Magnesium Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 1958–1963. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.10.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durdu S.; Aytaç A.; Usta M. Characterization and Corrosion Behavior of Ceramic Coating on Magnesium by Micro-Arc Oxidation. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 8601–8606. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.06.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfoori A.; Mirdamadi S.; Khavandi A.; Raufi Z. S. Biodegradation Behavior of Micro-Arc Oxidized AZ31 Magnesium Alloys Formed in Two Different Electrolytes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 261, 92–100. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.07.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong K.; Song Y.; Shan D.; Han E.-H. Corrosion Behavior of a Self-Sealing Pore Micro-Arc Oxidation Film on AM60 Magnesium Alloy. Corros. Sci. 2015, 100, 275–283. 10.1016/j.corsci.2015.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. M.; Shin K. R.; Namgung S.; Yoo B.; Shin D. H. Electrochemical Response of ZrO2-Incorporated Oxide Layer on AZ91 Mg Alloy Processed by Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, 3779–3784. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2011.01.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnev V. S.; Ustinov A. Y.; Vaganov-Vil’kins A. A.; Nedozorov P. M.; Yarovaya T. P. Fabrication of Polytetrafluoroethylene- and Graphite-Containing Oxide Layers on Aluminum and Titanium and Their Structure. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 87, 1021–1026. 10.1134/S0036024413060228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke B. M.; Zhang L.; Li W.; Ning C.; Chen C.-f.; Gu Y. Corrosion performance of MAO coatings on AZ31 Mg alloy in simulated body fluid vs. Earle’s Balance Salt Solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 363, 328–337. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sankara Narayanan T. S. N.; Park I. S.; Lee M. H. Strategies to improve the corrosion resistance of microarc oxidation (MAO) coated magnesium alloys for degradable implants: Prospects and challenges. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 60, 1–71. 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2013.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hakimizad A.; Raeissi K.; Santamaria M.; Asghari M. Effects of pulse current mode on plasma electrolytic oxidation of 7075 Al in Na2WO4 containing solution: From unipolar to soft-sparking regime. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 284, 618–629. 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.07.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maqbool A.; Hussain M. A.; Khalid F. A.; Bakhsh N.; Hussain A.; Kim M. H. Mechanical characterization of copper coated carbon nanotubes reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Mater. Charact. 2013, 86, 39–48. 10.1016/j.matchar.2013.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem M.; Hwan L. D.; Kim I.-s.; Kim M.-S.; Maqbool A.; Nisar U.; Pervez S. A.; Farooq U.; Farooq M. U.; Khalil H. M. W.; Jeong S.-J. Revealing of core shell effect on frequency-dependent properties of Bi-based relaxor/ferroelectric ceramic composites. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14146. 10.1038/s41598-018-32133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem M.; Butt M. S.; Maqbool A.; Umer M. A.; Shahid M.; Javaid F.; Malik R. A.; Jabbar H.; Khalil H. M. W.; Hwan L. D.; et al. Percolation phenomena of dielectric permittivity of a microwave-sintered BaTiO3–Ag nanocomposite for high energy capacitor. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 822, 153525. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.153525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y.; Bandopadhyay S.; Chen C.-f.; Guo Y.; Ning C. Effect of Oxidation Time on the Corrosion Behavior of Micro-Arc Oxidation Produced AZ31 Magnesium Alloys in Simulated Body Fluid. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 543, 109–117. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.07.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blawert C.; Heitmann V.; Dietzel W.; Nykyforchyn H. M.; Klapkiv M. D. Influence of Process Parameters on the Corrosion Properties of Electrolytic Conversion Plasma Coated Magnesium Alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 200, 68–72. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2005.02.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. G.; Zhu X. P.; Lei M. K. Electrochemical Properties of Microarc Oxidation Films on a Magnesium Alloy Modified by High-Intensity Pulsed Ion Beam. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 206, 874–878. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2011.04.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]