Abstract

Background

Barrier dysfunction is recognized as a pathogenic factor in ulcerative colitis (UC) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but it is unclear to what extent the factors related to barrier dysfunction are disease-specific. The aim of this study was to compare these aspects in UC patients in remission, IBS patients, and healthy controls (HCs).

Methods

Colonic biopsies were collected from 13 patients with UC in remission, 15 patients with IBS-mixed, and 15 HCs. Ulcerative colitis patients had recently been treated for relapse, and biopsies were taken from earlier inflamed areas. Biopsies were mounted in Ussing chambers for measurements of intestinal paracellular permeability to 51chromium (Cr)-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). In addition, biopsies were analyzed for mast cells and eosinophils by histological procedures, and plasma tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α was assessed by ELISA.

Results

Ussing chamber experiments revealed an increased 51Cr-EDTA permeability in UC and IBS (P < 0.05). The 51Cr-EDTA permeability was higher in UC compared with IBS (P < 0.005). There were increased numbers of mucosal mast cells and eosinophils in UC and IBS and more eosinophils in UC compared with IBS (P < 0.05). Also, increased extracellular granule content was found in UC compared with HCs (P < 0.05). The 51Cr-EDTA permeability correlated significantly with eosinophils in all groups. Plasma TNF-α concentration was higher in UC compared with IBS and HCs (P < 0.0005).

Conclusions

Results indicate a more permeable intestinal epithelium in inactive UC and IBS compared with HCs. Ulcerative colitis patients, even during remission, demonstrate a leakier barrier compared with IBS. Both eosinophil numbers and activation state might be involved in the increased barrier function seen in UC patients in remission.

Keywords: eosinophils, intestinal permeability, irritable bowel syndrome, mast cells, ulcerative colitis

Main results from this study indicate a more permeable intestinal epithelium in inactive UC and IBS compared with HCs. Moreover, UC patients, even during remission, demonstrate a leakier barrier compared with IBS, which seems to be associated with eosinophils.

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are 2 chronic gastrointestinal (GI) entities with incompletely understood pathophysiology. Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by intermittent flares of bloody stools and increased stool frequency. Unlike IBS, UC features macroscopic mucosal inflammation during active disease. Irritable bowel syndrome is one of the most common functional bowel disorders characterized by recurring abdominal pain and associated with disturbed bowel habits.1 In terms of mucosal barrier function studies, the majority of abnormalities found in UC and IBS are based on the comparison of healthy controls (HCs) with either UC patients2–4 or IBS patients.5–7 However, to evaluate if the barrier function disturbances demonstrated in UC and IBS are disease-specific or generalizable for both disorders, control studies are needed. Today, there are only few such studies directly comparing barrier function of UC and IBS.8, 9 It is well known that there also exists a clinical overlap between UC and IBS because patients with UC in remission often report IBS-like symptoms that do not necessarily correspond to a low-grade inflammation, even though increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines have been reported.10

A low-grade mucosal inflammation is often present in the colon and ileum of IBS patients, characterized by mast cells, T cells, and pro-inflammatory cytokines.11, 12 Ahn et al13 showed that patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) had significantly more colonic mast cells and T cells in relation to HCs but had similar counts when compared with UC patients in remission. Nevertheless, colonic tissue from IBS-D patients had significantly fewer immune cells than the colon from patients with mildly activated UC.

A barrier dysfunction is well recognized as an important pathogenic factor in UC,2–4 and an impaired barrier function has become evident also in IBS.5–7 There are few studies comparing gut barrier function in IBS and UC in remission. Gecse et al8 found that intestinal permeability was elevated in patients with IBS-D and inactive UC compared with HCs by measuring 24-hour urine excretion of orally administered 51Chromium (Cr)-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). In another study by Vivinus-Nébot et al,9 both IBS (all subtypes) and quiescent UC patients with IBS-like symptoms showed higher paracellular permeability compared with HCs, as measured using fluorescein isothiocyanate-sulfonic acid in Ussing chambers, but they found no difference between HCs and quiescent UC patients with no IBS-like symptoms. To our knowledge, there is to date no study directly comparing the colonic barrier function between IBS, UC in remission, and HCs by using biopsies and permeability markers in Ussing chambers—a gold standard technique for the assessment of intestinal permeability ex vivo.

There is substantial evidence for an elevated number and increased degranulation of mast cells and secretion of mediators in UC14–16 and IBS.5, 17, 18 In addition, some studies have implicated mast cells in the regulation of intestinal permeability.19–21 Our group previously found an increased number of mast cells and their activation in the colonic mucosa in IBS compared with HCs and an increased permeability in colonic biopsies of IBS patients, which was significantly diminished after stabilizing the mast cells with ketotifen.5 In addition, we recently demonstrated higher amounts of mast cells in the colonic mucosa of UC and Crohn’s disease patients compared with HCs.16 Together, this indicates that mast cells have an important role in both IBS and IBD, including UC, and are also important regulators of barrier function. The intestinal mucosa contains moderate amounts of active eosinophils.22 However, it is known that the numbers of activated eosinophils are increased in patients with active and inactive UC.23 Furthermore, the numbers have shown to be higher in the mucosa of inactive UC compared with the inflamed mucosa,23 suggesting that eosinophils may play diverse roles in the pathophysiology of IBD—both pro-inflammatory and mediating tissue repair. Moreover, a close interaction between eosinophils and mast cells, potentially leading to a disrupted mucosal barrier and increased permeability, has been demonstrated in IBD.24, 25 For IBS, colon studies have shown inconsistent results with both increased26, 27 and unaltered eosinophil counts.28

A better knowledge about the differences between IBS and UC in remission are important for a deeper understanding of the disease-specific barrier function disturbances in these disorders. The present study was designed to search for similarities and differences in epithelial barrier function and related immune cells between UC in remission and IBS. Colonic biopsies from patients with inactive UC, IBS, and HC patients were mounted in Ussing chambers to assess paracellular permeability. Mucosal mast cells and eosinophils were quantified; intracellular and extracellular tryptase and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), respectively, were analyzed; and plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α were measured.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The material included 13 patients with inactive UC, 15 patients with IBS, and 15 HCs, recruited from the Gastroenterology Department, University Hospital, Linköping, Sweden. Inclusion criteria for the UC group was clinical and endoscopic remission and treatment for relapse within the last year. Biopsies were taken from the earlier inflamed area. Inclusion criteria for the IBS group was that patients were classified in the IBS-mixed (IBS-M) subgroup based on the predominant stool consistency according to the Rome III questionnaire.29 The HCs were recruited by advertisement, and inclusion criteria was that patients had no medical history of chronic GI symptoms or disorders and no medication intake. Exclusion criteria for all groups included metabolic or neurological disorders. The Committee of Human Ethics, Linköping, approved the study, and all subjects gave their written informed consent.

Collection of Biological Samples

A flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed in all participants, and colonic biopsies were taken from the sigmoideum, rectosigmoidal junction, or rectum. All biopsies were taken with forceps without a central lance and directly put in ice-cold oxygenated Krebs buffer (115 mM NaCl, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM KH2PO4, and 25 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.35). Before sigmoidoscopy, venous blood samples were collected in EDTA-treated tubes, blood was centrifuged at 3400g for 15 minutes in 4°C, and plasma was redrawn and frozen in −80°C until analysis of TNF-α concentration.

Ussing Chamber Experiments

Colonic biopsies were mounted in Ussing chambers (Harvard Apparatus Inc., Holliston, MA, USA) as previously described.30 After 40 minutes of equilibration, 34 µCi/mL of the paracellular probe 51Cr-EDTA (Perkin Elmer, MA, USA) was added to the mucosal side of each chamber. Serosal samples were collected at 0, 60, and 120 minutes, and 51Cr-EDTA passage was measured by gamma-counting (1282 Compugamma, Sweden). The 51Cr-EDTA permeability was calculated during the 60 to 120 minute period, and results are presented as Papp (apparent permeability coefficient; cm/s ×10-6). The transepithelial potential difference (PD) and the transepithelial resistance (TER) across the tissues were monitored throughout the experiments to ensure tissue viability.

Measurements of TNF-α Concentration in Plasma

An ultrasensitive human TNF-α ELISA kit was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lund, Sweden). Undiluted plasma, positive and negative controls, and standard points were added in duplicates. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm in VERSAmax Tunable Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) using Softmax pro 5 (Molecular Devices).

Staining of Mast Cells and Eosinophils in the Colonic Mucosa

Immediately after collection, colonic biopsies were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline for 24 hours at 4°C and further embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 µm. Upon use, slides were hydrated according to standard procedures.

Mast cells

Sections were incubated with background sniper (Histolab, Gothenburg, Sweden) for 5 minutes. Slides were rinsed and incubated over night at 4°C with mouse monoclonal-antihuman mast cell tryptase 1:200 (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Slides were rinsed and incubated with 1:400 secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated rabbit-antimouse (Life Technologies, Stockholm, Sweden) for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were rinsed and mounted with Prolong Gold-DAPI (Life Technologies).

Eosinophils

Slides were incubated in Harris hematoxylin (Casa Alvarez, Madrid, Spain) for 4 minutes. After brief rinsing in tap water, slides were immersed in 1% hydrochloric alcohol for 10 seconds, re-immersed in tap water, and immersed in tap water with 2 to 3 ammonia drops for 1 minute. Finally, slides were incubated in eosin (Casa Alvarez) for 1 minute and mounted with Pertex mounting media (Histolab).

Quantification of Mast Cells and Eosinophils

The total number of mucosal mast cells and eosinophils was quantified in a blinded fashion by 2 independent researchers in a Nikon E800 fluorescence microscope connected to software NIS elements (Nikon Instruments Inc. Tokyo, Japan). The number of cells positive for tryptase or eosin were quantified manually at 400x magnification, and negative controls were included in all experiments. A minimum of 8 areas/sections was counted. Every area had the same size, and only areas that were covered completely by the biopsy were used. The mean value for each section was estimated for mast cell tryptase expression or eosin and a median value of the number of mast cells and eosinophils from patients with UC, IBS, and HCs, respectively.

Distribution of mast cell tryptase and eosinophil-ECP and cell ultrastructure

To study the granule distribution and activation levels of eosinophils and mast cells, biopsies from randomly selected subjects, 4 UC patients in remission, 4 IBS-M patients and 4 HCs, were processed for immunofluorescence and evaluated with confocal microscopy. Mast cells were identified using antihuman tryptase following the protocol described previously for mast cell quantification. Similarly, eosinophils were identified with antihuman ECP 1:200 (Diagnostic Development, Uppsala, Sweden), an eosinophil activation marker. Slides were stained using the same protocol described previously for mast cells quantification, with an additional antigen retrieval step with citrate buffer at 60°C for 30 minutes. One transversal section/individual was used for each staining, and negative controls were included in all experiments. From 8 to 14 images of single mast cells or eosinophils (single when possible) were acquired with LSM800 Zeiss Inverted Confocal with a 60X oil immersion objective. Images were processed in ImageJ Fiji software (NIH, Bethseda, MD), followed by the analysis with Cell Profiler 2.2.0 software. Nuclei signal was used, together with tryptase or ECP signal, to delimit and segment the cell limits of mast cell and eosinophils, respectively. All the granules detected inside those limits were defined as intracellular; the granules localized outside the cellular limits were defined as extracellular content and interpreted as an indicative of degranulation levels. After threshold, the average of integrated intensity per cell and the extracellular content surrounding the cell were measured. Finally, a median value was calculated from all the averages to create a median of intensity expressed with arbitrary units (AUs).

To further identify and illustrate signs of mast cell and eosinophil activation, biopsies were processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Biopsies from all groups were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 24 to 72 hours, postfixed, dehydrated, and further processed according to standard protocols for TEM. Representative photographs of mast cells and eosinophils were achieved using a Hitachi H-1400 electron microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 7 Software (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). All data, except electrophysiology data, were confirmed as normally distributed and given as mean ±SEM. Comparisons between these groups were done with Student t or ANOVA test. Electrophysiology data (TER) was given as median (25th to 75th percentile), and comparisons between groups were done with the Mann-Whitney U test when there were 2 groups or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn multiple comparisons test when there were multiple groups. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered significant. Correlation testing was done with 2-tailed Pearson correlation test. Influence on the results of different parameters related to patient’s characteristics (as indicated in Table 1) was analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U and Spearman correlation tests (continuous variable and stratification).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics of the 13 Patients with UC in Remission and 15 Patients with IBS-mixed and 15 Healthy Controls Included in the Study

| UC | IBS | HCs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 36 (21–72) years | 31 (19–52) years | 27 (21–61) years |

| Sex | 7 women, 6 men | 15 women | 11 women, 4 men |

| Biopsy location | Sigmoideum (n = 7) | Sigmoideum (n = 15) | Sigmoideum (n = 10) |

| Rectum (n = 6) | Rectosigmoidal junction (n = 5) | ||

| Endoscopic Mayo score | 0 (n = 12) | 0 (n = 15) | 0 (n = 15) |

| 1 (n = 1) | |||

| Anti-inflammatory medication | 5-ASA (n = 12) | None | None |

| Steroids (n = 1) | |||

| Infliximab (n = 1) | |||

| Azathioprine (n = 3) | |||

| Allergy/smoking | Pollen (n = 2) | None | None |

| Pollen & fur (n = 1) | |||

| Smoking (n = 2) |

Biopsies were taken in October-December that is outside pollen season in Sweden.

RESULTS

Patients and HCs

The material included 13 patients with inactive UC, 15 patients with IBS-M, and 15 HCs (Table 1). All UC patients were in clinical and endoscopic remission (Full Mayo score ≤2).31 At the day of endoscopy, UC patients graded the presence of abdominal pain for the previous day, (none, mild, moderate, or severe). Four patients reported mild abdominal pain, and 1 reported moderate abdominal pain. All IBS patients were classified in the IBS-M subgroup and had moderate-severe symptoms with median symptom severity score (SSS)32 of 343 (range 167–462), and none of the patients related the onset of their symptoms to infectious gastroenteritis. Measurements of plasma-C-reactive protein (p-CRP) showed that all UC patients had p-CRP <10 mg/mL (median 2.1, range 0.2–7.1) when biopsies were achieved. Analyses showed that biopsy location (rectum/rectosigmoidal junction/sigmoideum) had no significant impact on any of the results.

Decreased TER in UC and IBS Compared With HCs

Ussing chamber experiments showed a stable PD after equilibration in all biopsies, indicating a good tissue viability throughout the experiments (data not shown) and ensuring that differences observed were not due to differences in viability between biopsies.

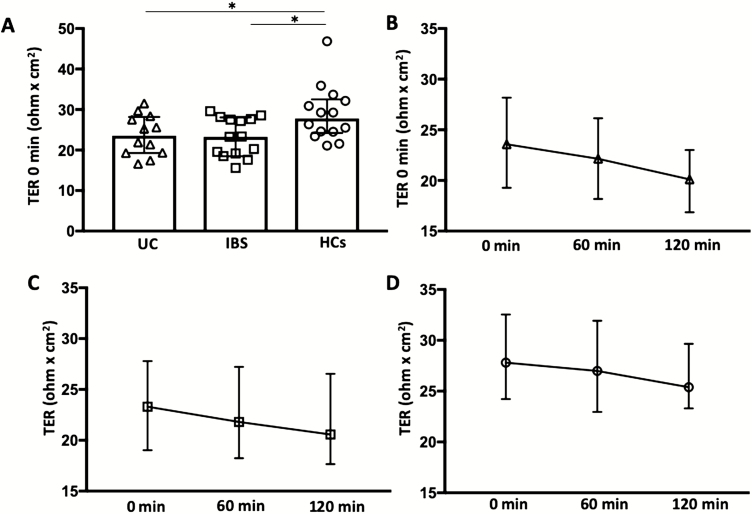

Ussing chamber experiments revealed a lower TER in biopsies from both UC and IBS patients compared with HCs already at time 0 (P < 0.05; Fig. 1A). Transepithelial resistance remained lower after both 60 and 120 minutes from start, both in UC (60 min, 22.1 [18.2–26.1] ohm × cm2, P < 0.05; 120 min, 20.1 [16.9–23.0], P < 0.005) and IBS (60 min, 21.8 [18.2–27.2], P < 0.05; 120 min, 20.6 [17.7–26.5], P < 0.05) compared with HCs (60 min, 27.0 [23.0–31.9]; 120 min, 25.4 [23.3–29.7]). Changes of TER over time, 0 to 120 minutes, are shown in Figs. 1B–D.

FIGURE 1.

A, Transepithelial resistance (TER) measured at start, 0 min, in colonic biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis in remission, irritable bowel syndrome, and healthy controls. Bars represent median (25th–75th percentile). B–D, Changes of TER over time in UC (B), IBS (C), and HCs (D). Graphs show median TER values and the variability at each time point (25th–75th percentile). Comparisons between 2 groups were done with Mann-Whitney U test. *P < 0.05.

Increased Paracellular Permeability in UC and IBS

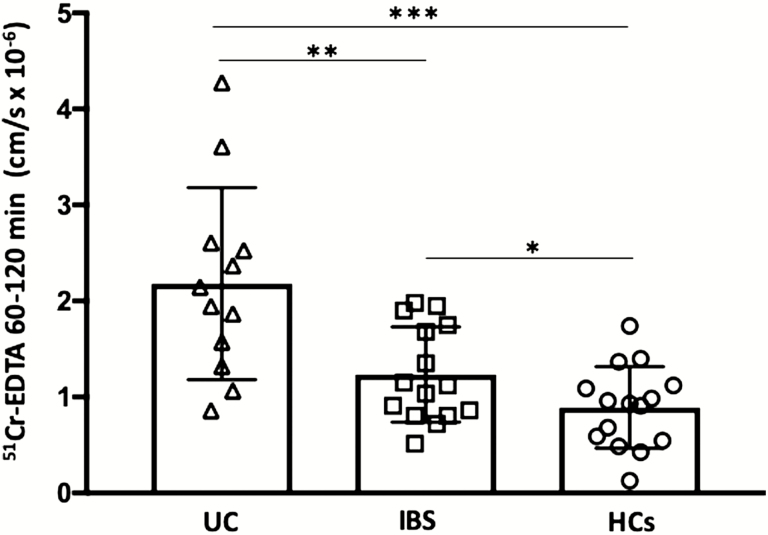

Permeability to 51Cr-EDTA over time (60–120 min) was higher in both UC (P < 0.0005) and IBS (P < 0.05) compared with HCs. Moreover, paracellular permeability was significantly higher in UC biopsies compared with IBS (P < 0.005; Fig. 2). A higher paracellular permeability was not correlated to a higher grade of abdominal pain in UC patients (r = 0.34, P = 0.27), but notably, the highest permeability of 51Cr-EDTA (4.3 cm/s ×10-6) was recorded in the single UC patient who graded the presence of abdominal pain as moderate. In line with this, there was no correlation between 51Cr-EDTA permeability and IBS SSS (r = 0.15, P = 0.31); however, the 2 IBS patients displaying the 2 highest SSS values displayed the 2 highest 51Cr-EDTA permeability measurements (1.75 and 1.95 cm/s ×10-6, respectively).

FIGURE 2.

Paracellular permeability to 51Chromium (Cr)-EDTA in colonic biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis in remission, irritable bowel syndrome, and healthy controls. Biopsies were mounted in Ussing chambers, and permeability to 51Cr-EDTA was measured over the 60–120 min period after start. Bars represent median (25th–75th percentile), and comparisons between 2 groups were done with Mann-Whitney U test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005.

Increased TNF-α in Plasma of UC Patients in Remission

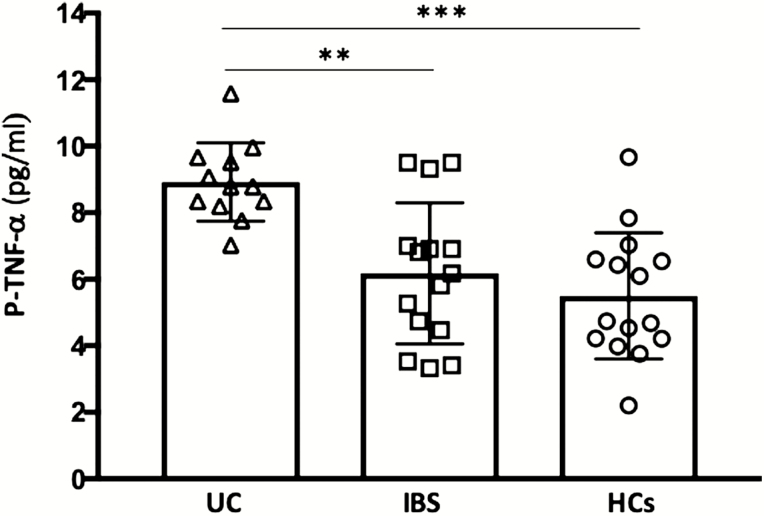

ELISA revealed higher TNF-α levels in plasma of UC compared with both IBS (P < 0.005) and HCs (P < 0.0005), whereas there was no significant difference between IBS and HCs (Fig. 3). There was no significant correlation between plasma TNF-α concentrations and 51Cr-EDTA permeability.

FIGURE 3.

Concentrations of TNF-α in plasma from patients with ulcerative colitis in remission, irritable bowel syndrome, and healthy controls. Bars represent median (25th–75th percentile), and comparisons between 2 groups were done with Mann-Whitney U test. **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005.

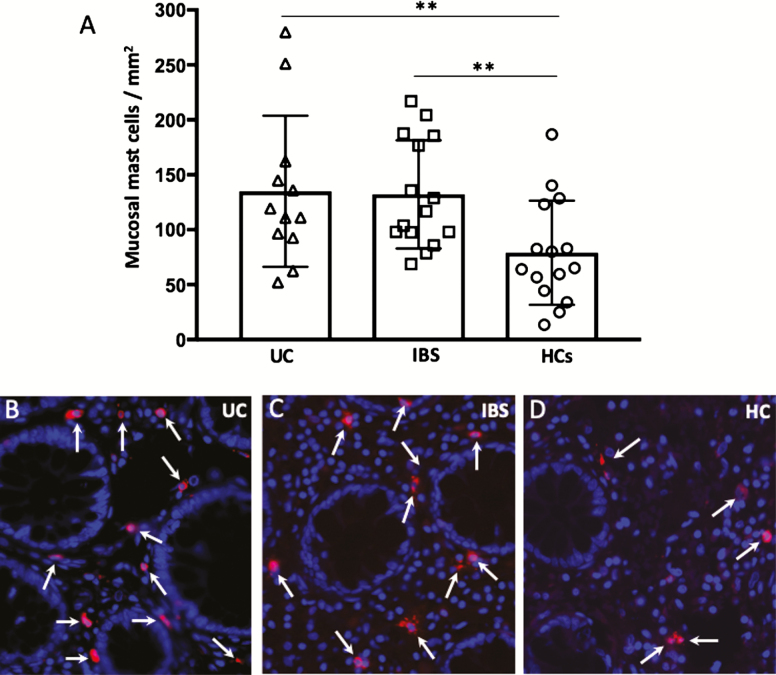

Increased Number of Mucosal Mast Cells in UC and IBS Compared With HCs

Colonic biopsies from both UC and IBS patients showed increased number of mast cells compared with HCs (P < 0.05; Fig. 4A). However, there was no difference in the number of mast cells between UC (144.7 ± 19.2 cells/mm2) and IBS (132.1 ± 12.7 cells/mm2). Representative photomicrographs of tryptase-positive cells are shown in Figure 4B–D.

FIGURE 4.

A, Mucosal mast cells quantified by immunofluorescence in colonic biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis in remission, irritable bowel syndrome, and healthy controls. B–D, Representative photographs of mast cell tryptase-positive cells (red, arrows) in the colonic mucosa of UC, IBS, and HC, respectively. Blue, nuclei staining by DAPI. Magnification 600X. Bars represent median (25th–75th percentile), and comparisons between 2 groups were done with Mann-Whitney U test. **P < 0.005.

The majority of both UC (85%) and IBS (85%) had higher mast cell numbers compared with the mean of HCs. This indicates recruitment of mast cell progenitors from the circulation into tissues of almost all IBS and UC patients.

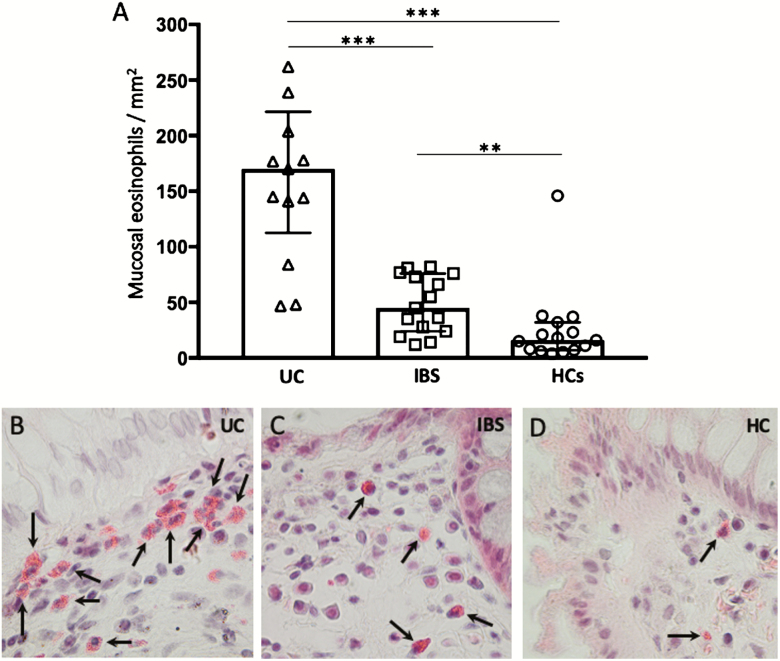

Increased Number of Mucosal Eosinophils in UC Compared with IBS and HCs

Eosin staining revealed an increased number of eosinophils in both UC (P < 0.0005) and IBS (P < 0.005) compared with HCs (Fig. 5A). In contrast to mast cells, the number of eosinophils was significantly elevated in UC mucosa compared with IBS (P < 0.0005). Representative photographs of cells identified as eosinophils are shown in Figure 5B–D. Eosinophils were often found just beneath the epithelial cell border; in UC, they were often found in clusters, as illustrated in Figure 5B. When comparing microscopy results patient by patient, it was shown that 100% of the UC patients and approximately 69% of the IBS patients had elevated eosinophil numbers compared with the mean of HCs. This indicates that a mucosal immune activation seems to be present in almost all patients.

FIGURE 5.

A, Graph showing mucosal eosinophils quantified by hematoxylin and eosin staining in colonic biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis in remission, irritable bowel syndrome, and healthy controls. B–D, Photographs illustrating cells positive for eosin (arrows) in the colonic mucosa of UC, IBS, and HC, respectively. Magnification 600X. Bars represent median (25th–75th percentile), and comparisons between 2 groups were done with Mann-Whitney U test. **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005.

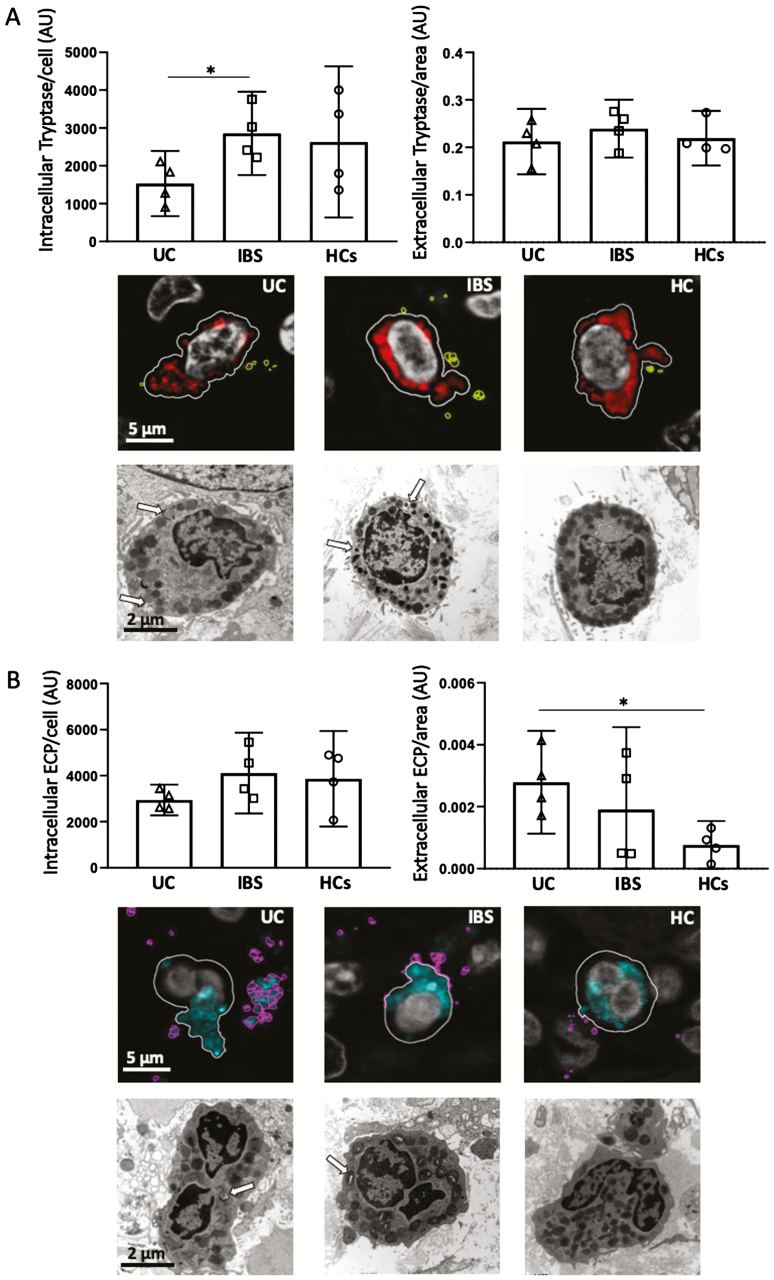

Decreased intracellular tryptase in mast cells in UC

Intracellular and extracellular tryptase were quantified in single mast cells with confocal microscopy in biopsies from 4 UC patients (mean ±SD, 39.2 ± 9.2 years; 2 women), 4 patients with IBS-M (30.8 ± 6.2 years; 4 women) and 4 HCs (36 ± 7.9 years; 4 women). Intracellular measurements showed significant decreased tryptase content in mast cells of UC patients compared with IBS (P < 0.05), but no difference was found in extracellular tryptase surrounding the cells (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Mast cell tryptase and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) distribution in colonic biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis in remission, irritable bowel syndrome, and healthy controls. A, Quantification of intracellular/extracellular tryptase. Representative images of mast cells with identification of plasma cell membrane (white line), and tryptase located at intracellular (red) and extracellular (green) compartments. Ultrastructural analysis identifies partial degranulation of cytoplasmic granules (white arrow) in UC and IBS, indicative of activation, and a more stable phenotype in HC. B, Quantification of intracellular/extracellular ECP. Representative images of eosinophils with identification of plasma cell membrane (white line) and ECP located at intracellular (blue) and extracellular (pink) compartments. Ultrastructural analysis identifies partial degranulation of some cytoplasmic granules (white arrow) in UC and IBS, indicative of activation, and a more stable phenotype in HC. Quantification was done in 600X confocal images and expressed in arbitrary units. Bars represent median (25th–75th percentile), and comparisons were done with Mann-Whitney U test. *P < 0.05.

Ultrastructural visual analysis identified signs of activation in mast cells from all samples, with higher heterogeneity in granular electrodensity and pseudopodes in the UC and IBS groups. Representative images are shown in Figure 6A.

Increased extracellular ECP in eosinophils in UC

Intracellular and extracellular ECP were quantified in single or eosinophils (a few clustered) in biopsies from patients with UC, IBS-M, and HC patients as indicated for mast cells. Even though intracellular ECP was not significantly different among groups, measurements showed increased extracellular ECP content in UC compared with HCs (P < 0.05; Fig. 6B).

Ultrastructural visual analysis of eosinophils showed an activated profile, with larger cytoplasmic granules in the UC group and partial degranulation of some cytoplasmic granules in UC and IBS groups as compared with HCs. Representative images are shown in Figure 6B.

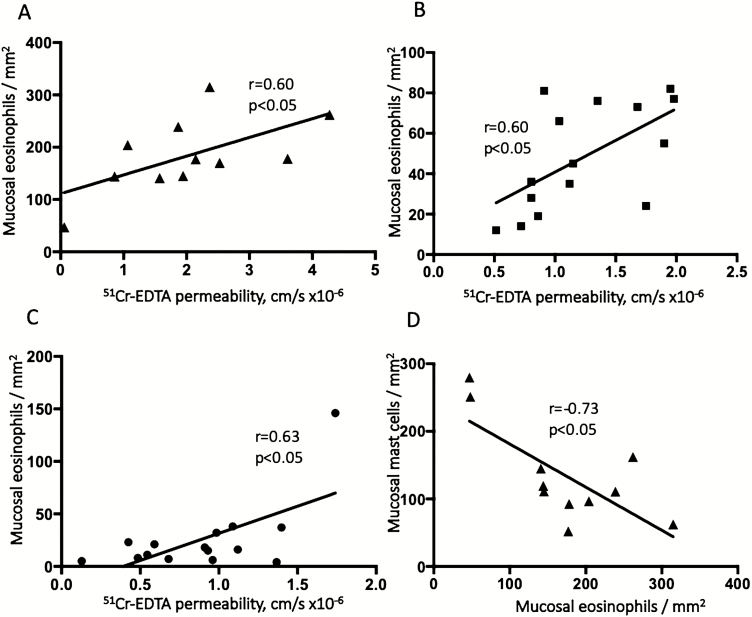

Increased Paracellular Permeability Correlated to Number of Eosinophils

Correlation analysis of the measured parameters (TER, 51Cr-EDTA permeability, mast cells, eosinophils, and plasma TNF-α concentrations) showed significant associations between paracellular permeability to 51Cr-EDTA and the number of eosinophils in all groups: UC (r = 0.60, P < 0.05), IBS (r = 0.60, P < 0.05), and HCs (r = 0.63, P < 0.05) (Fig. 7A–C). However, no significant correlation was found between 51Cr-EDTA and the number of mast cells in any of the groups. Interestingly in UC patients, the number of mast cells was negatively correlated to the number of eosinophils (r = −0.73, P < 0.05; Fig. 7D). In HCs, there was a correlation between 51Cr-EDTA permeability and TNF-α concentrations in plasma (r = 0.66, P < 0.05), though no significant correlations could be found in UC or IBS patients. Transepithelial resistance did not correlate with any of the other parameters (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

A–C, The correlation between eosinophil numbers and paracellular permeability to 51Chromium (Cr)-EDTA in colonic biopsies from patients with inactive ulcerative colitis (A), patients with irritable bowel syndrome (B), and healthy controls (C). The correlation between the number of eosinophils and mast cells in colonic biopsies from ulcerative colitis patients is illustrated (D). Correlation testing was done with 2-tailed Pearson correlation test.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that intestinal paracellular permeability was increased in both patients with inactive UC and IBS-M patients and that this increase was more evident in UC patients in remission in comparison with IBS-M patients. In addition, both inactive UC and IBS-M patients had significantly more mucosal mast cells and eosinophils than HCs, but only the number of eosinophils was significantly higher in UC in remission compared with IBS-M. Also, a significantly increased level of eosinophil degranulation, identified by higher amounts of extracellular ECP, could only be observed in UC. Furthermore, there was a significant positive correlation between eosinophil numbers and paracellular permeability to 51Cr-EDTA in all groups.

There is a realization that among other factors such as low-grade inflammation and genetic susceptibility, increased intestinal permeability also contributes to the pathophysiology of both IBS5–7 and UC.2–4 Moreover, it is known that a great percentage of patients with quiescent UC present IBS symptoms.33 Our findings suggest that increased paracellular permeability might be a pathophysiological feature typical for both diseases. The electrophysiological measurements monitored throughout the Ussing chamber experiments demonstrated a lower TER in both UC and IBS biopsies as compared with HCs. This difference was detected from the start of experiments, suggesting structural changes in the integrity of the paracellular pathways. Ussing experiments further showed an increased paracellular permeability in both UC and IBS compared with HCs. This is in line with a previous study,8 showing an increased colonic permeability to orally administrated 51Cr-EDTA measured by 24-hour urine excretion in both inactive UC and IBS-D compared with HCs. Interestingly, the increase in permeability was correlated to stool frequency in IBS patients—but not in UC patients. We previously showed25 an increased transcellular passage but an unaltered paracellular permeability in biopsies from quiescent UC patients. However, these patients were in deep remission and had not had a relapse in several years, in comparison with the UC patients of the present study.

There was a higher number of mucosal mast cells in colonic biopsies of both UC patients in remission and IBS-M patients in remission compared with HCs, as revealed by immunofluorescence. The fact that the amount of mast cells seems to follow the same pattern both in inactive UC and IBS could indicate that mast cells are a contributing factor to the increased paracellular permeability and, therefore, to the pathogenesis of these diseases, as is also shown previously.14 Though, there was neither a correlation between 51Cr-EDTA permeability and mast cell quantity nor a difference in mast cell numbers between UC and IBS, which indicates that mast cell amounts may not be responsible for the increased paracellular permeability observed in UC compared with IBS. It might be that despite an unaltered number, there could be a difference in the granular content or activation status of the mast cells. Even though our results showed similar release of tryptase in both IBS and UC compared with HCs, it could still be a difference in granular content. There is a different mucosal environment that is of higher inflammatory degree in UC compared with IBS and HCs.18 Mast cells adapt their granular content to external factors; therefore, it would be of interest in future studies to identify which mediators are differentially produced in each entity. Previously, it was shown that the content of mast cells differs not only between healthy controls and IBD but also between UC and CD patients.34 Furthermore, Lloyd et al showed already in 1975 that there was a marked degranulation of intestinal mast cells in CD compared with healthy controls.35 This was confirmed later on by Dvorak et al who described in more detail, using transmission electron microscopy, an enhanced degranulation of intestinal mast cells in patients with both CD36 and UC.37 Other studies showed similar results in both CD and UC, using antibody specific immunohistochemistry against human mast cell markers tryptase and chymase.38

In the present study, histological staining with eosin revealed significantly more eosinophils in both inactive UC and IBS-M colonic biopsies compared with HCs. Interestingly, the number of eosinophils was significantly elevated in UC compared with IBS, and degranulation analysis revealed significantly more degranulated eosinophils in UC compared with both IBS-M and HCs. Moreover, when looking at the data, it was indicated that the number of eosinophils seemed to correlate to the extracellular ECP levels in UC patients. Even though there were too few subjects to draw any conclusion, this preliminary observation might suggest that the function of ECP is the key to the role of eosinophils. In line with this, Bystrom et al39 previously reported that ECP levels in patients with other conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, lung disease, and various autoimmune conditions robustly correlated with the number of eosinophils present.

The reason for the increased number of eosinophils might be due to a higher recruitment of eosinophils during UC compared with IBS. During active bowel inflammation, eosinophils are known to migrate to the GI tract in response to chemokines (eg, RANTES and eotaxin, both constitutively expressed throughout the gut). Eotaxin binds to the CCR-3 receptor on eosinophils, which is required for their homing to the GI tract.40 It is, however, known that other cytokines are needed as well, among them interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-13 and TNF-α, which all increase the circulating number of eosinophils and prime them to enhance their response to eotaxin.40 Pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to be elevated during active disease compared with inactive disease; 41 however, during both active and inactive phases of UC, significant levels of eotaxin has been reported in serum.42 It might be that, compared with IBS, there is a different cytokine milieu in the mucosa of patients with UC—even during remission—with somewhat enhanced levels of cytokines promoting the recruitment of eosinophils. The eotaxin CCL11 and IL-5 were increased in both active and inactive UC, and CCL11 was positively correlated to eosinophil numbers,43 supporting its contribution to eosinophil recruitment. Moreover, Carlson et al44 showed increased release of eosinophil granule proteins in the noninflamed mucosa of patients with UC compared with controls, and Lampinen et al showed more activated eosinophils in the colon of inactive UC patients compared with active disease patients.23 Further, the early activation marker CD69 showed to be more expressed in inactive UC compared with active,45 and in addition, monocyte chemotactic factor‐4 and IL-33, known to activate human eosinophils, were increased compared with controls in both active and inactive UC.45 These findings indicate eosinophil activity in the noninflamed colon, which could refer to the cytokines in the microenvironment. In addition, there might be other stimulus of eosinophil recruitment and activation present during remission; however, this needs to be further investigated.

An interesting observation was that eosinophils appeared to concentrate just beneath the epithelium, and in UC, they were often found in clusters. In contrast, mast cells were more seldom found this close to the epithelial cell lining—and especially not in UC. One might speculate that the proximity of clustered eosinophils and the epithelial barrier could contribute to increased permeability in UC. Eosinophil quantity was positively correlated to paracellular permeability in all groups, which is noteworthy because no correlation could be found between 51Cr-EDTA permeability and mast cells. This might be interpreted at first that the eosinophil number could have a higher impact on paracellular permeability than mast cells in the colonic mucosa. However, it could also be inferred that the increased amount and/or activation of eosinophils give rise to an enhanced secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), for example.24 As we previously described,25 CRH can activate mast cells, and upon activation, mast cells start secreting a wide variety of bioactive mediators such as TNF-α, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-16, and IFNγ. Several of these mediators have effects on mucosal barrier function (eg, chymase, tryptase,46 IFNγ, and TNF-α).47 In this study, TNF-α levels were higher in plasma of UC patients compared with both IBS and HC patients. This, together with the correlation observed between paracellular permeability and eosinophil numbers, suggests an indirect involvement of mast cells, even though the effect on the barrier might be due to activation state rather than amount of mast cells.

One of the HCs had a very high number of eosinophils, 146 cells/mm2, in comparison with the mean of HCs that was 25.8 cells/mm2. This HC did not report any allergies, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or any other known diseases that could otherwise explain the enhanced eosinophil count.48 However, there could be a nonsymptomatic parasite infection49 or disease (eg, vasculitis),50 where eosinophils are involved, of which the HC was not aware. Colonic eosinophilia is known to be caused by conditions such as allergies, parasitic infections, or drugs, and it is also a hallmark of IBD and eosinophilic colitis.50, 51 In the present study, the presence or absence of allergies did not have any impact on any of the results; however, we do not have enough data to confidently exclude other conditions, as mentioned previously, that could influence the results as far as colon eosinophils are concerned.

Surprisingly, we found that the number of mast cells was negatively correlated to the number of eosinophils in UC in remission. This could be partly explained by ongoing treatment with aminosalicylate (5-ASA) in the UC patients, as it has been shown (at least in IBS patients) that this treatment causes downregulation of mast cells.52 To our knowledge, data on the effect of 5-ASA on mast cells in UC are lacking; however, it seems reasonable to extrapolate the results of the previous study also to UC patients in remission. Whether 5-ASA could cause proportional increase of mucosal eosinophils is not known, although several cases of 5-ASA–induced eosinophilic disorders have been described.53 The specific increase in eosinophils seen in UC is probably related to other factors, as well. For example, it could be speculated that 5-ASA can have effects on cell maturation and progenitors. In contrast to our findings, in asthma and eosinophilic esophagitis, the levels of eosinophils and mast cells generally mirror each other.54 However, 5-ASA treatment is generally not used in these conditions. In addition, our finding of a negative correlation between eosinophils and mast cells in UC might seem contradictory to our previous data25 regarding eosinophils secreting CRH, which activates mast cells to secrete mediators affecting the barrier. Our degranulation analyses showed no difference in extracellular tryptase in UC. This could either indicate that eosinophils have a more prominent role compared with mast cells in UC barrier dysfunction or that the 5-ASA treatment drastically downregulates mast cell activation levels. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanism behind this.

Our findings of significantly higher TNF-α levels in UC plasma compared with IBS and HC—and comparable TNF-α levels in IBS and HCs—are consistent with previous studies55 and in line with common knowledge that IBS does not seem to be a TNF-driven disease, in contrast to UC. There was no correlation between TNF-α levels in plasma and paracellular permeability in UC or IBS patients; however, a correlation was found in HCs. This might simply be explained by the fact that the levels of 51Cr-EDTA permeability, and especially TNF-α, are overall low in healthy controls which might give rise to the observed correlation between them.

In conclusion, our findings indicate a more permeable mucosa in patients with inactive UC and patients with moderate to severe IBS compared with HCs. Ulcerative colitis patients, even during remission, display a leakier mucosal barrier compared with IBS, where eosinophils might be involved. Results further suggest a generalizable association between eosinophils and paracellular permeability; however, because of the cross-sectional design of the study, we were not able to demonstrate causality. This was also true for patients with IBS and HCs. The present results contribute to a better understanding of colonic paracellular permeability in patients with UC in remission and IBS, though more studies are needed to confirm this in a larger material.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all the patients for participating in this study. They also thank Mr. Martin Winberg, Linköping University, for assistance in the Ussing laboratory and Mrs. Lena Svensson, Linköping University, for the embedding and sectioning of samples. Further, they acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Alejandro Sánchez-Chardi and Francisca Cardoso, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, for technical assistance and excellent performance in electron microscopy procedures.

Author Contribution: GK contributed to the inclusion of HC and UC patients, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and the drafting of the article and approved the final version. MCB contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data, the drafting of the article, and approved the final version. SAW contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, and the drafting of the article and approved the final version. MV contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data and the drafting of the article and approved the final version. AMGC contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data and the drafting of the article and approved the final version. OB contributed to the inclusion of HC and IBS patients and the drafting of the article and approved the final version. JDS contributed to the interpretation of data, revised it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version. HH contributed to the interpretation of data, revised it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version. ÅVK contributed to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, and was mainly responsible for drafting the final version of the article before approval.

Supported by: This work was supported by grants from Bengt Ihre research Scholarship (ÅVK), AFA research foundation (SAW); Bengt-Ihre fonden, County Council of Östergötland (SAW), the Swedish Research Council (VR-Medicine and Health, 2017-02475) (JDS, ÅVK), and the Swedish Foundation For Strategic Research (RB13-016). It was upported in part by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (PI16/00583, MV), and Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Spain (CIBER-EHD CB06/04/0021, MV).

REFERENCES

- 1. Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1393–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jenkins RT, Ramage JK, Jones DB, et al. Small bowel and colonic permeability to 51Cr-EDTA in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Invest Med. 1988;11:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arslan G, Atasever T, Cindoruk M, et al. (51)CrEDTA colonic permeability and therapy response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22:997–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Teahon K, Somasundaram S, Smith T, et al. Assessing the site of increased intestinal permeability in coeliac and inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1996;38:864–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bednarska O, Walter SA, Casado-Bedmar M, et al. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and mast cells regulate increased passage of colonic bacteria in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:948–960.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dunlop SP, Hebden J, Campbell E, et al. Abnormal intestinal permeability in subgroups of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1288–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piche T, Barbara G, Aubert P, et al. Impaired intestinal barrier integrity in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: involvement of soluble mediators. Gut. 2009;58:196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gecse K, Róka R, Séra T, et al. Leaky gut in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and inactive ulcerative colitis. Digestion. 2012;85:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vivinus-Nébot M, Frin-Mathy G, Bzioueche H, et al. Functional bowel symptoms in quiescent inflammatory bowel diseases: role of epithelial barrier disruption and low-grade inflammation. Gut. 2014;63:744–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jonefjäll B, Öhman L, Simrén M, et al. IBS-like symptoms in patients with ulcerative colitis in deep remission are associated with increased levels of serum cytokines and poor psychological well-being. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2630–2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohman L, Isaksson S, Lindmark AC, et al. T-cell activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1205–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. An S, Zong G, Wang Z, et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in mast cells contributes to the regulation of inflammatory cytokines in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1083–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ahn JY, Lee KH, Choi CH, et al. Colonic mucosal immune activity in irritable bowel syndrome: comparison with healthy controls and patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1001–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Winter BY, van den Wijngaard RM, de Jonge WJ. Intestinal mast cells in gut inflammation and motility disturbances. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. He SH. Key role of mast cells and their major secretory products in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Casado-Bedmar M, Heil SDS, Myrelid P, et al. Upregulation of intestinal mucosal mast cells expressing VPAC1 in close proximity to vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in inflammatory bowel disease and murine colitis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31:e13503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guilarte M, Santos J, de Torres I, et al. Diarrhoea-predominant IBS patients show mast cell activation and hyperplasia in the jejunum. Gut. 2007;56:203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cremon C, Gargano L, Morselli-Labate AM, et al. Mucosal immune activation in irritable bowel syndrome: gender-dependence and association with digestive symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Neunlist M, Toumi F, Oreschkova T, et al. Human ENS regulates the intestinal epithelial barrier permeability and a tight junction-associated protein ZO-1 via VIPergic pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G1028–G1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bakker R, Dekker K, De Jonge HR, et al. VIP, serotonin, and epinephrine modulate the ion selectivity of tight junctions of goldfish intestine. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:R362–R368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Conlin VS, Wu X, Nguyen C, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide ameliorates intestinal barrier disruption associated with Citrobacter rodentium-induced colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G735–G750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Winterkamp S, Raithel M, Hahn EG. Secretion and tissue content of eosinophil cationic protein in Crohn’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lampinen M, Rönnblom A, Amin K, et al. Eosinophil granulocytes are activated during the remission phase of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54:1714–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zheng PY, Feng BS, Oluwole C, et al. Psychological stress induces eosinophils to produce corticotrophin releasing hormone in the intestine. Gut. 2009;58:1473–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wallon C, Persborn M, Jönsson M, et al. Eosinophils express muscarinic receptors and corticotropin-releasing factor to disrupt the mucosal barrier in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Park KS, Ahn SH, Hwang JS, et al. A survey about irritable bowel syndrome in South Korea: prevalence and observable organic abnormalities in IBS patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Silva AP, Nandasiri SD, Hewavisenthi J, et al. Subclinical mucosal inflammation in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in a tropical setting. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Sullivan M, Clayton N, Breslin NP, et al. Increased mast cells in the irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2000;12:449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keita AV, Gullberg E, Ericson AC, et al. Characterization of antigen and bacterial transport in the follicle-associated epithelium of human ileum. Lab Invest. 2006;86:504–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fukuba N, Ishihara S, Tada Y, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome-like symptoms in ulcerative colitis patients with clinical and endoscopic evidence of remission: prospective multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:674–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sasaki Y, Tanaka M, Kudo H. Differentiation between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease by a quantitative immunohistochemical evaluation of T lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes and mast cells. Pathol Int. 2002;52:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lloyd G, Green FH, Fox H, et al. Mast cells and immunoglobulin E in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1975;16:861–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dvorak AM, Monahan RA, Osage JE, et al. Crohn’s disease: transmission electron microscopic studies. II. Immunologic inflammatory response. Alterations of mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, and the microvasculature. Hum Pathol. 1980;11:606–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dvorak AM, McLeod RS, Onderdonk A, et al. Ultrastructural evidence for piecemeal and anaphylactic degranulation of human gut mucosal mast cells in vivo. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1992;99:74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bischoff SC, Wedemeyer J, Herrmann A, et al. Quantitative assessment of intestinal eosinophils and mast cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Histopathology. 1996;28:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bystrom J, Amin K, Bishop-Bailey D. Analysing the eosinophil cationic protein–a clue to the function of the eosinophil granulocyte. Respir Res. 2011;12:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Filippone RT, Sahakian L, Apostolopoulos V, et al. Eosinophils in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:1140–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Inoue S, Matsumoto T, Iida M, et al. Characterization of cytokine expression in the rectal mucosa of ulcerative colitis: correlation with disease activity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2441–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mir A, Minguez M, Tatay J, et al. Elevated serum eotaxin levels in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1452–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lampinen M, Waddell A, Ahrens R, et al. CD14+CD33+ myeloid cell-CCL11-eosinophil signature in ulcerative colitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carlson M, Raab Y, Peterson C, et al. Increased intraluminal release of eosinophil granule proteins EPO, ECP, EPX, and cytokines in ulcerative colitis and proctitis in segmental perfusion. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1876–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lampinen M, Fredricsson A, Vessby J, et al. Downregulated eosinophil activity in ulcerative colitis with concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;104:173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wilcz-Villega EM, McClean S, et al. Mast cell tryptase reduces junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A) expression in intestinal epithelial cells: implications for the mechanisms of barrier dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1140–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li Q, Zhang Q, Wang M, et al. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha disrupt epithelial barrier function by altering lipid composition in membrane microdomains of tight junction. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jiménez-Sáenz M, González-Cámpora R, Linares-Santiago E, et al. Bleeding colonic ulcer and eosinophilic colitis: a rare complication of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:84–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Al Samman M, Haque S, Long JD. Strongyloidiasis colitis: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Alfadda AA, Storr MA, Shaffer EA. Eosinophilic colitis: epidemiology, clinical features, and current management. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4:301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lucendo AJ. Cellular and molecular immunological mechanisms in eosinophilic esophagitis: an updated overview of their clinical implications. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:669–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V, Cremon C, et al. Effect of mesalazine on mucosal immune biomarkers in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled proof-of-concept study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bartal C, Sagy I, Barski L. Drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia: a review of 196 case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e9688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Galdiero MR, Varricchi G, Seaf M, et al. Bidirectional mast cell-eosinophil interactions in inflammatory disorders and cancer. Front Med (Lausanne). 2017;4:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chang L, Adeyemo M, Karagiannides I, et al. Serum and colonic mucosal immune markers in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:262–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]