Abstract

The objective of this study was to compare the virulence of 3 major Korean porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) genotypes in terms of clinical signs, PCV2 viremia and antibody titers, lymphoid lesions, and PCV2-antigen within lymphoid lesions in experimentally infected pigs. Pigs were infected at 7 weeks with PCV2a, PCV2b, and PCV2d strains and necropsied at 28 days post-infection. No statistical differences were observed in clinical signs, PCV2 viremia and antibody titers, lymphoid lesions scores, and numbers of PCV2 antigens among the 3 major Korean PCV2 genotypes. The results of this study indicate that the 3 major Korean PCV2 genotypes, PCV2a, PCV2b, and PCV2d, have similar virulence.

Résumé

L’objectif de la présente étude était de comparer la virulence de trois génotypes majeurs de circovirus porcine de type 2 (PCV2) coréens en termes de signes cliniques, virémie de PCV2 et titres d’anticorps, lésions lymphoïdes et antigènes de PCV2 à l’intérieur des lésions lymphoïdes chez des porcs infectés expérimentalement. Les porcs furent infectés à 7 semaines d’âge avec les souches PCV2a, PCV2b et PCV2d et soumis à une nécropsie 28 jours post-infection. Aucune différence significative ne fut observée dans les signes cliniques, la virémie de PCV2 et les titres d’anticorps, les pointages de lésions lymphoïdes et les nombres d’antigènes de PCV2 pour les trois génotypes majeurs de PCV2 coréens. Les résultats de cette étude indiquent que les trois génotypes majeurs de PCV2 coréens, PCV2a, PCV2b et PCV2d ont une virulence similaire.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) is the smallest non-enveloped, single-stranded, circular deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) virus belonging to the genus Circovirus and the family Circoviridae (1). It is the most common etiological agent associated with several syndromes and diseases that are now collectively referred to as porcine circovirus-associated disease (PCVAD) (2).

Today, PCV2 is prevalent worldwide with 5 different genotypes recognized so far based on the sequence identity in open reading frame 2 (ORF2). The genotypes have been designated with lowercase letters (a, b, c, d, and e) based on the order of the first identification, with PCV2a, PCV2b, and PCV2d being the major genotypes. Porcine circovirus type 2c (PCV2c) has only been isolated from Danish tissues archived in the late 1990s (3) and in feral pigs in Brazil (4). The 5th genotype, PCV2e, has been reported in the USA and China, but so far has a very low prevalence (5).

Currently, PCV2d has become the predominant genotype in North America, Asia, and Europe. While all 3 major genotypes (a, b, and d) are considered virulent and etiological agents of PCVAD, the degree of virulence is somewhat controversial. A previous study concluded that Chinese PCV2d strains caused a more serious disease than PCV2a or PCV2b (6). In contrast, a North American PCV2d strain exhibited similar virulence to PCV2a and PCV2b strains in cesarean-derived, colostrum-deprived pigs (7). So far, no comparison studies have been done on the virulence of the Korean genotypes. The objective of this study was to compare the virulence of 3 major Korean PCV2 genotypes in terms of clinical signs, PCV2 viremia and antibody titers, lymphoid lesion scores, and PCV2-antigen present within lymphoid lesions in experimentally infected pigs.

The strains used in this study were: PCV2a strain SNUVR000032 (GenBank no. KF871067), which shares 98.8% to 99.1% and 99% nucleotide sequence identity of the full genome with 3 US PCV2a strains (GenBank no. AY099499, AF264041, and AJ223185) and 1 European PCV2a strain (GenBank no. AJ293868), respectively; PCV2b strain SNUVR000463 (GenBank no. KF871068), which shares 99.3% to 99.5% and 99.6% to 99.8% nucleotide sequence identity of the full genome with 2 US PCV2b strains (GenBank no. HQ713495 and GU799576) and 3 European PCV2b strains (GenBank no. AY484416, DQ233257, and AF055393), respectively; and PCV2d strain SNUVR140004 (GenBank no. KJ437506), which shares 99.70% and 96.5% to 98% nucleotide sequence identity of the full genome with 2 US PCV2d strains (GenBank no. JX535297 and JX535296) and 2 European PCV2d strains (GenBank no. AY484410 and AY713470), respectively.

Forty clinically healthy, colostrum-fed conventional pigs from sows that had not been previously vaccinated against PCV2 were purchased at 14 d old from a commercial farm that was free of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). It was also determined that the farm was free of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae based on serological testing and long-term clinical and slaughter history. Pigs were also tested with commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (PRRSV: HerdChek PRRS X3 Ab Test; IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, Maine, USA; PCV2: Synbiotics, Lyon, France; M. hyopneumoniae: M. hyo. Ab Test; IDEXX Laboratories) and were seronegative for PRRSV, PCV2, and M. hyopneumoniae.

For the study, pigs were allocated into 4 groups (10 pigs per group) using the random number generation function from Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) (Table I). Pigs in each group were randomly assigned into 4 separate rooms. On the day of infection (7 wk old), pigs in the PCV2a-infected group were inoculated intranasally with 2 mL (1 mL/nostril) of tissue culture supernatant containing 105 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50)/mL of PCV2a (SNUVR000032, GenBank no. KF871067, 5th passage in PCV-free PK-15 cell lines) (8). Pigs in the PCV2b-infected group were inoculated intranasally with 2 mL (1 mL/nostril) of tissue culture supernatant containing 105 TCID50/mL of PCV2b (SNUVR000463, GenBank no. KF871068, 5th passage in PCV-free PK-15 cell lines) (8). Pigs in the PCV2d-infected group were inoculated intranasally with 2 mL (1 mL/nostril) of tissue culture supernatant containing 105 TCID50/mL of PCV2d (SNUVR140004, GenBank no. KJ437506, 5th passage in PCV-free PK-15 cell lines) (9). Pigs in the negative control group were inoculated intranasally with 2 mL (1 mL/nostril) of uninfected cell culture supernatant. Blood samples were collected from each pig by jugular venipuncture at −28, 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28 d post-infection (dpi). All pigs were euthanized for necropsy at 28 dpi after sedation by intravenous (IV) azaperon (Stersnil; Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium). All experimental protocols were approved before the study by the Seoul National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Table I.

Average daily weight gain and pathology data (mean ± standard deviation) of 10 pigs in each of 4 groups at 28 d post-infection.

| Groups | PCV2a-infected | PCV2b-infected | PCV2d-infected | Negative control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average daily weight gain (49 to 77 d old) | 533.21 ± 37.80 | 534.29 ± 37.47 | 531.43 ± 32.16 | 569.64 ± 29.17 |

| Lymphoid lesion scores | 1.40 ± 0.23a | 1.52 ± 0.19a | 1.42 ± 0.27a | 0.00 ± 0.00b |

Different superscripts (a and b) indicate significant (P < 0.05) difference among 4 groups.

Pigs were monitored daily for clinical signs and scored weekly. Briefly, scoring was defined as follows: 0 = normal; 1 = rough hair coat; 2 = rough hair coat and dyspnea; 4 = severe dyspnea and abdominal breathing; 5 = rough hair coat with severe dyspnea and abdominal breathing; and 6 = death. The live weight of each pig was measured at 49 and 77 d old. The average daily weight gain (ADWG; gram/pig/day) was analyzed over the time period from 49 to 77 d old and was calculated during the different production stages as the difference between the starting and final weight, divided by the duration of the stage. Data for dead or removed pigs were included as well in the calculation.

Serum samples were collected at −28, 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28 dpi and DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genomic DNA copy numbers for PCV2a, PCV2b, and PCV2d were quantified by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (10–12). The detection limit of the assay was 1.2 × 102 genomic copies for each of the 3 PCV2 genotypes. Serum samples were also tested for antibodies against PCV2 (PCV2 Ab Mono Blocking; Synbiotics). Samples were considered positive for PCV2 antibodies if the reciprocal ELISA titer was greater than 350 according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For the morphometric analysis of histopathological changes in superficial inguinal lymph nodes, 3 sections of that lymph node were examined “blindly” (13). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and morphometric analysis of IHC were carried out as previously described (14). Lymph nodes were evaluated for the presence of lymphoid depletion and inflammation and given a score ranging from 0 to 5 (0 = normal; 1 = mild lymphoid depletion; 2 = mild to moderate lymphoid depletion and histiocytic replacement; 3 = moderate diffuse lymphoid depletion and histiocytic replacement; 4 = moderate to severe lymphoid depletion and histiocytic replacement; 5 = severe lymphoid depletion and histiocytic replacement).

Prior to statistical analysis, RT-PCR data were log-transformed to reduce variance and positive skewness. Statistics were calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Data were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine whether there were statistically significant differences among the 4 groups, for each time point. When a test result from 1-way ANOVA showed a statistical significance, a post-hoc test was conducted for a pairwise comparison with Tukey’s adjustment. If the normality assumption was not met, the Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted. When the result from the Kruskal-Wallis test showed statistical significance, the Mann-Whitney test with Tukey’s adjustment was done to compare the differences among the groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Pigs in the PCV2a-, PCV2b-, and PCV2d-infected groups had significantly more severe (P < 0.05) clinical signs than the negative control group at 21 and 28 dpi. There was no significant difference in clinical signs among PCV2a-, PCV2b-, and PCV2d-infected groups at 7, 14, 21, and 28 dpi. There was no significant difference in ADWG among PCV2a-, PCV2b-, and PCV2d-infected groups over the time period from 49 to 77 d old. There was a numerical, but not statistically significant difference in ADWG between PCV2 (PCV2a, PCV2b, and PCV2d)-infected groups and the negative control group (Table I).

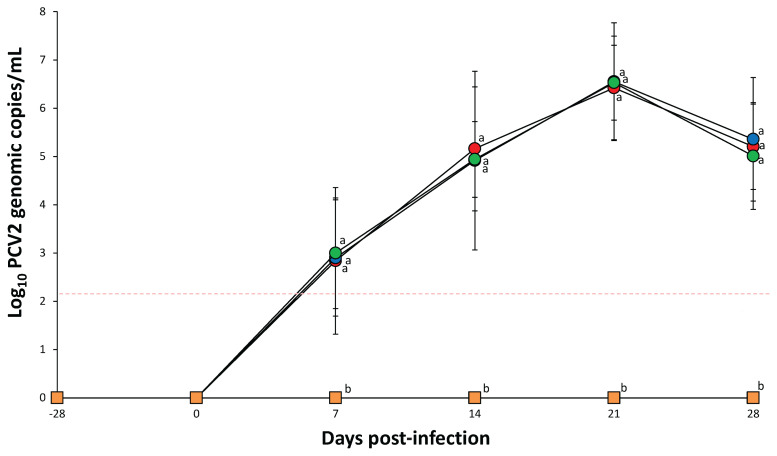

At the time of challenge, no genomic copies of PCV2 could be detected in any of the serum samples collected from all 4 groups. At 7, 14, 21, and 28 dpi, the number of genomic copies of the respective PCV2a, PCV2b, and PCV2d DNA was similar among PCV2a-, PCV2b-, and PCV2d-infected groups (Figure 1). Pigs in the PCV2ainfected group were negative for PCV2b and PCV2d DNA, pigs in the PCV2b-infected group were negative for PCV2a and PCV2d DNA, and pigs in the PCV2d-infected group were negative for PCV2a and PCV2b DNA throughout the experiment. No PCV2a, PCV2b, or PCV2d genomes were detected in the sera of pigs from the negative control group throughout the study.

Figure 1.

Mean values of the genomic copy number of PCV2 DNA in serum from PCV2a-infected (

n = 10 pigs); PCV2b-infected (

n = 10 pigs); PCV2b-infected (

n = 10 pigs); PCV2d-infected (

n = 10 pigs); PCV2d-infected (

n = 10 pigs); and negative control (

n = 10 pigs); and negative control (

n = 10 pigs) groups. The detection limit of the assay was 1.2 × 102 genomic copies for each of the 3 PCV2 genotypes (red dotted line). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to compare the 4 treatment groups. Tukey’s adjustment was used for a post-hoc analysis. For not normally distributed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test and consequently the Mann-Whitney test were used to evaluate differences among the treatment groups. Variation is expressed as the standard deviation. Different superscripts (a and b) indicate significant (P < 0.05) difference among 4 groups.

n = 10 pigs) groups. The detection limit of the assay was 1.2 × 102 genomic copies for each of the 3 PCV2 genotypes (red dotted line). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to compare the 4 treatment groups. Tukey’s adjustment was used for a post-hoc analysis. For not normally distributed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test and consequently the Mann-Whitney test were used to evaluate differences among the treatment groups. Variation is expressed as the standard deviation. Different superscripts (a and b) indicate significant (P < 0.05) difference among 4 groups.

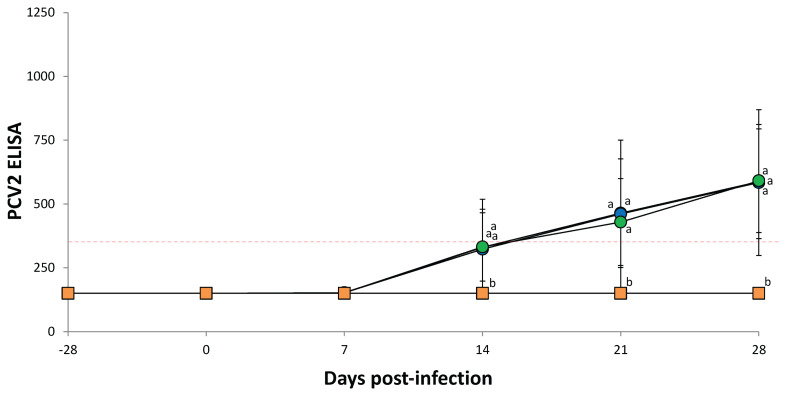

At the time of challenge, serum samples collected from all 4 groups were negative for PCV2 antibodies. At 7, 14, 21, and 28 dpi, pigs from all infected groups exhibited similar PCV2 antibody levels regardless of genotype. Pigs in the negative control group were negative for PCV2 antibodies throughout the study (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PCV2-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody levels in serum from PCV2a-infected (

n = 10 pigs); PCV2b-infected (

n = 10 pigs); PCV2b-infected (

n = 10 pigs); PCV2d-infected (

n = 10 pigs); PCV2d-infected (

n = 10 pigs); and negative control (

n = 10 pigs); and negative control (

n = 10 pigs) groups. Serum samples are considered to be positive for anti-PCV2 antibody if the reciprocal ELISA titer is > 350 (red dotted line). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to compare the 4 treatment groups. Tukey’s adjustment was used for post-hoc analysis. For not normally distributed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test and consequently the Mann-Whitney test were used to evaluate differences among the treatment groups. Variation is expressed as the standard deviation. Different superscripts (a and b) indicate significant (P < 0.05) difference among 4 groups.

n = 10 pigs) groups. Serum samples are considered to be positive for anti-PCV2 antibody if the reciprocal ELISA titer is > 350 (red dotted line). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to compare the 4 treatment groups. Tukey’s adjustment was used for post-hoc analysis. For not normally distributed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test and consequently the Mann-Whitney test were used to evaluate differences among the treatment groups. Variation is expressed as the standard deviation. Different superscripts (a and b) indicate significant (P < 0.05) difference among 4 groups.

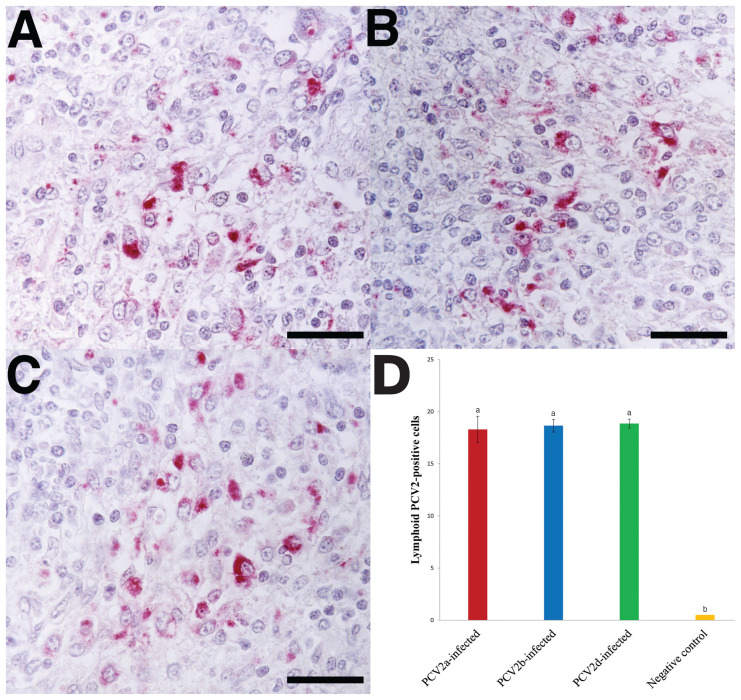

Pigs in the PCV2a-, PCV2b-, and PCV2d-infected groups had significantly higher (P < 0.05) lymphoid lesion scores (Table I). PCV2 antigen positive cells were detected in the PCV2a-infected (Figure 3A), PCV2b-infected (Figure 3B), and PCV2d-infected (Figure 3C) groups. Pigs in the PCV2a-, PCV2b-, and PCV2d-infected groups had a significantly higher (P < 0.05) number of lymphoid PCV2-positive cells than the negative control group (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for detecting PCV2 antigens in lymph node. A — Representative IHC for detecting PCV2 antigens in lymph node from the PCV2a-infected group. Bar = 55 μm. B — Representative IHC for detecting PCV2 antigens in lymph node from the PCV2b-infected group. Bar = 55 μm. C — Representative IHC for detecting PCV2 antigens in lymph node from the PCV2d-infected group. Bar = 55 μm. D — Numbers of lymphoid PCV2 antigen-positive cells in lymph node from PCV2a-, PCV2b-, and PCV2d-infected groups. Numbers of PCV2 antigen-positive cells per unit are (0.25 mm2) of lymph node from 10 pigs per group were counted using an NIH Image J 1.45s program. (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to compare the 4 treatment groups. Tukey’s adjustment was used for a post-hoc analysis. For not normally distributed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test and consequently the Mann-Whitney test were used to evaluate differences among the treatment groups. Different superscripts (a and b) indicate significant (P < 0.05) difference among 4 groups.

The evidence presented in this study demonstrates that there is no significant difference in virulence among the 3 major Korean PCV2 genotypes, PCV2a, PCV2b, and PCV2d. We should be cautious when interpreting these results, however, as even though PCV2 is the primary agent of PCVAD, a single infection with PCV2 does not always reproduce a full manifestation of clinical PCVAD observed on pig farms (15). Thus, a single infection model may not be the most representative when comparing the virulence of PCV2 genotypes. There is evidence that there are both mild and virulent PCV2 strains for each genotype (16,17). In addition, co-infection of PCV2 with other viruses, such as porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), could potentiate the virulence of mild virulent PCV2 strains. Therefore, further studies are needed to accurately compare the virulence of each PCV2 genotype by analyzing both single-infection and co-infection models.

Potential differences in virulence among the various genotypes have been the subject of recent debate. A previous study showed that infection with a Chinese PCV2d strain can result in more severe disease than PCV2a or PCV2b infections (7). In contrast, a study that used North American isolates for all 3 genotypes (a, b, d) reported no significant difference in virulence (8). In our study, we compared Korean isolates for each genotype and observed no significant differences in virulence, similar to the North American isolates. It is interesting to note, however, that even though no significant differences in virulence were observed among the 3 genotypes for Korean and North American isolates, the pattern of PCV2 viremia among genotypes is somewhat different when comparing isolates from Korea and North America. When comparing levels of PCV2 viremia with the North American isolates, the amount of PCV2 DNA in serum samples at 7 dpi was significantly higher in pigs infected with PCV2d than in those infected with PCV2b (8). In contrast, no statistical differences were observed in levels of viremia among all 3 major Korean PCV2 genotypes throughout our study. It should be noted, however, that the route of infection in this study was through intranasal inoculation only, whereas the previous 2 studies (7,8) used both intranasal and intramuscular inoculations. It is possible that the route of infection could have an effect on the virulence. Further studies are needed to directly compare PCV2 genotypes using the same route of infection.

Even though PCV2a or PCV2b are still highly prevalent, the PCV2d genotype has now become the predominant genotype in Korea (18). Severe economic losses to the Korean pig industry due to PCVAD underscore the need for a comparative study of the virulence of the 3 major PCV2 genotypes. Additionally, most of the PCV2 vaccines now available are based on the PCV2a genotype. Cross-protection of the PCV2a vaccines against PCV2d infection is critical because, according to the Korean Animal Health Products Association, about 96.05% of total piglets farrowed in 2017 in Korea were vaccinated with PCV2a-based vaccines. While 2 commercial PCV2a-based vaccines have been shown to protect pigs against experimental challenge with a North American PCV2d strain (19,20), further studies are needed to determine whether the current PCV2a vaccines can provide efficient cross-protection against Korean PCV2d strains.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ research was supported by contract research funds from the Research Institute for Veterinary Science (RIVS) of the College of Veterinary Medicine and by the BK 21 Plus Program (Grant no. 5260-20150100) for Creative Veterinary Science Research.

References

- 1.Mankertz A, Persson F, Mankertz J, Blaess G, Buhk HJ. Mapping and characterization of the origin of DNA replication of porcine circovirus. J Virol. 1997;71:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2562-2566.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chae C. A review of porcine circovirus 2-associated syndromes and diseases. Vet J. 2005;169:326–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupont K, Nielsen EO, Bækbo P, Larsen LE. Genomic analysis of PCV2 isolates from Danish archives and a current PMWS case-control study supports a shift in genotypes with time. Vet Microbiol. 2008;128:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franzo G, Cortey M, de Castro AMMG, et al. Genetic characterisation of Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) strains from feral pigs in the Brazilian Pantanal: An opportunity to reconstruct the history of PCV2 evolution. Vet Microbiol. 2015;178:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies B, Wang X, Dvorak CMT, Marthaler D, Murtaugh MP. Diagnostic phylogenetics reveals a new Porcine circovirus 2 cluster. Virus Res. 2016;217:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo L, Fu Y, Wang Y, et al. A porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) mutant with 234 amino acids in capsid protein showed more virulence in vivo, compared with classical PCV2a/b strain. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opriessnig T, Xiao CT, Gerber PF, Halbur PG, Matzinger SR, Meng XJ. Mutant USA strain of porcine circovirus type 2 (mPCV2) exhibits similar virulence to the classical PCV2a and PCV2b strains in caesarean-derived, colostrum-deprived pigs. J Gen Virol. 2014;95:2495–2503. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.066423-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo HW, Han K, Park C, Chae C. Clinical, virological, immunological and pathological evaluation of four porcine circovirus type 2 vaccines. Vet J. 2014;200:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seo HW, Park C, Han K, Chae C. Effect of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) vaccination on PCV2-viremic piglets after experimental PCV2 challenge. Vet Res. 2014;45:13. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-45-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagnon CA, del Castillo JR, Music N, Fontaine G, Harel J, Tremblay D. Development and use of a multiplex real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay for detection and differentiation of Porcine circovirus-2 genotypes 2a and 2b in an epidemiological survey. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008;20:545–558. doi: 10.1177/104063870802000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Opriessnig T, Xiao CT, Gerber PF, Halbur PG. Emergence of a novel mutant PCV2b variant associated with clinical PCVAD in two vaccinated pig farms in the U.S. concurrently infected with PPV2. Vet Microbiol. 2013;163:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong J, Park C, Choi K, Chae C. Comparison of three commercial one-dose porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) vaccines in a herd with concurrent circulation of PCV2b and mutant PCV2b. Vet Microbiol. 2015;177:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J, Chae C. Expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 in porcine circovirus 2-induced granulomatous inflammation. J Comp Pathol. 2004;131:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim D, Kim CH, Han K, et al. Comparative efficacy of commercial Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) vaccines in pigs experimentally infected with M. hyopneumoniae and PCV2. Vaccine. 2011;29:3206–3212. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harms PA, Sorden SD, Halbur PG, et al. Experimental reproduction of severe disease in CD/CD pigs concurrently infected with type 2 porcine circovirus and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet Pathol. 2001;38:528–539. doi: 10.1354/vp.38-5-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Opriessnig T, McKweon NE, Zhou EM, Meng XJ, Halbur PG. Genetic and experimental comparison of porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) isolates from cases with and without PCV2-associated lesions provides evidence for differences in virulence. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2923–2932. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trible BR, Rowland RRR. Genetic variation of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) and its relevance to vaccination, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Virus Res. 2012;164:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon T, Lee DU, Yoo SJ, Je SH, Shin JY, Lyoo YS. Genotypic diversity of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) and genotype shift to PCV2d in Korean pig population. Virus Res. 2017;228:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opriessnig T, Gerber PF, Xiao CT, Mogler M, Halbur PG. A commercial vaccine based on PCV2a and an experimental vaccine based on a variant mPCV2b are both effective in protecting pigs against challenge with a 2013 U.S. variant mPCV2b strain. Vaccine. 2014;32:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opriessnig T, Xiao CT, Halbur PG, Gerber PF, Matzinger SR, Meng XJ. A commercial porcine circovirus (PCV) type 2a-based vaccine reduces PCV2d viremia and shedding and prevents PCV2d transmission to naive pigs under experimental conditions. Vaccine. 2017;35:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]