Abstract

Genome editing is essential for probing genotype-phenotype relationships and for enhancing chemical production and phenotypic robustness in industrial bacteria. Currently, the most popular tools for genome editing couple recombineering with DNA cleavage by the CRISPR nuclease Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes. Although successful in some model strains, CRISPR-based genome editing has been slow to extend to the multitude of industrially-relevant bacteria. In this review, we analyze existing barriers to implementing CRISPR-based editing across diverse bacterial species. We first compare the efficacy of current CRISPR-based editing strategies. Next, we discuss alternatives when the S. pyogenes Cas9 does not yield colonies. Finally, we describe different ways bacteria can evade editing and how elucidating these failure modes can improve CRISPR-based genome editing across strains. Together, this review highlights existing obstacles to CRISPR-based editing in bacteria and offers guidelines to help achieve and enhance editing in a wider range of bacterial species, including non-model strains.

Keywords: bacteria, nuclease, genome editing, CRISPR, recombineering

Introduction.

Genome editing has become a core “unit operation” when working with bacteria, enabling scientists to interrogate the genetic basis for their physiological and metabolic traits or to develop next-generation microbial chemical factories or probiotics [40, 43, 50, 51, 69, 87]. For bacteria that are culturable and transformable, a suite of traditional genome-editing approaches have been developed [14, 48, 52, 90], although the current state-of-the-art approach is to couple recombineering of a DNA template with DNA targeting by programmable nucleases from CRISPR-Cas systems [29, 39]. Such CRISPR-Cas nucleases, most notably the Cas9 nuclease from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), are directed by guide RNAs (gRNAs) to cleave complementary DNA sequences flanked by a specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [19, 34, 41]. The gRNAs can be encoded in two general forms: within a CRISPR array comprising alternating conserved repeats and targeting spacers that are naturally associated with CRISPR-Cas systems, or as a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) representing the processed form of a transcribed CRISPR array. In the case of Cas9, gRNAs encoded in a CRISPR array require co-expression of a tracrRNA and the presence of RNase III found in most bacteria [15], although the processed crRNA:tracrRNA hybrid can be encoded as a fused single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [34]. The recombineering template contains flanking homology arms and an internal sequence that disrupts the target site (e.g. mutations to the PAM), preventing targeting upon successful recombineering. Cleavage of unedited targets by CRISPR nucleases is often lethal in bacteria, serving as a strong counterselection. Cleavage may also drive editing through homologous recombination (HR) or, in some instances, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [72]. While the precise editing mechanism remains elusive and may vary, CRISPR nucleases have been used to achieve highly efficient genome editing in several bacteria [2, 26, 30, 57, 63]. The relatively simple design and ability to select for any type of edit without introducing a scar site makes genome editing with CRISPR advantageous over previous methods. However, CRISPR-based genome editing methods have been slow to extend beyond model strains of bacteria. This disconnect stands in contrast to the rapid rise of CRISPR-based tools in eukaryotes [16, 31, 54] and their direct relevance to industrial microbes [5, 17, 35].

In this review, we address existing challenges associated with applying CRISPR-based genome editing in bacteria. First, we analyze obstacles associated with the different available methods for CRISPR-based genome editing and emphasize that no predominant editing method currently exists. Then, we discuss why SpCas9 fails to yield colonies for certain bacteria, and we highlight several strategies to reduce cytotoxicity and achieve editing. Finally, we describe different failure modes to CRISPR-based editing in bacteria and underscore the importance of identifying these modes to improve editing methods. Overall, this review should be a useful resource for improving CRISPR-based genome editing efficiencies and for attempting editing in new strains.

Each CRISPR-based editing method has distinct advantages and disadvantages, yet direct comparisons are lacking.

CRISPR-based genome editing in bacteria was first demonstrated in E. coli in 2013 [30]. Since then, the application of CRISPR-based genome editing has been slowly expanding to other species (Table 1). Current editing strategies vary based on the employed CRISPR nuclease, the inclusion of heterologous recombineering machinery, the type of DNA recombineering template, and the number of plasmids utilized. Each parameter was likely chosen based on strain-specific characteristics (e.g. transformation/recombination efficiencies, availability of active recombinases, and consequences of double-stranded DNA breaks) as well as features of the desired edit. Despite this diversity, the reported methods can be classified into three distinct strategies based on the type of recombineering template used. We describe each strategy below, along with the distinct limitations that each possesses.

Table 1. Instances of CRISPR-based genome editing in bacteria.

The methods developed are categorized based on the CRISPR nuclease, inclusion of exogenous recombination machinery, type of recombineering template, and number of plasmids. Studies are noted that utilized either multiple strains (S) or multiple methods (M) to achieve editing.

| # | Species | Strain | CRISPR nuclease | Recombination machinery | Editing Template | Types of edits | # plasmids | Multiple strains (S), methods (M)? | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bacillus subtillis | B. subtilis 168 | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | deletion, SNP | 1 | - | 1 |

| deletion, insertion, SNP | 2 | - | 74 | ||||||

| 2 | Bacillus smithii | B. smithii ET 138 | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | deletion, insertion, SNP | 1 | - | 60 |

| 3 | Bacillus licheniformis | B. licheniformis DW2 | Cas9n | None | Plasmid | deletion, insertion | 1 | - | 44 |

| 4 | Clostridium acetobutylicum | C. acetobutylicum ATCC 824 | Cas9n | None | Plasmid | deletion | 1 | S | 46 |

| SpCas9 | deletion, insertion, SNP | 2 | - | 91 | |||||

| 5 | Clostridium beijerinckii | C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 | Cas9n | None | Plasmid | deletion | 1 | S | 46 |

| None (base editing) | C-T mutations | 1 | - | 47 | |||||

| 6 | Clostridium cellulolyticum | C. cellulolyticum H10 | Cas9n | None | Plasmid | deletion, insertion | 1 | - | 96 |

| 7 | Clostridium difficile | C. difficile R20291 | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | SNP | 1 | - | 57 |

| C. difficile 630 | deletion, insertion | 2 | - | 88 | |||||

| Cas12a | deletion | 1 | - | 24 | |||||

| 8 | Clostridium ljungdahlii | C. ljungdahlii DSM 13528 | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | deletion | 1 | - | 27 |

| 9 | Corynebacterium glutamicum | C. glutamicum ATCC13032 | Cas12a | RecT | ss oligo | SNP | 2 | M, S | 33 |

| C. glutamicum B1 | |||||||||

| C. glutamicum B226 | |||||||||

| C. glutamicum ATCC13032 | None | Plasmid | deletion, insertion | 1 | |||||

| ds linear or Plasmid | deletion | 1 | M | 102 | |||||

| 10 | Corynebacterium acetoacidophilam | C. acetoacidophilam B230 | Cas12a | RecT | ss oligo | SNP | 2 | M, S | 33 |

| C. acetoacidophilam B299 | |||||||||

| 11 | Corynebacterium pekinense | C. pekinense B3 | Cas12a | RecT | ss oligo | SNP | 2 | M, S | 33 |

| 12 | Corynebacterium crenatum | C. crenatum B6 | Cas12a | RecT | ss oligo | SNP | 2 | M, S | 33 |

| 13 | Escherichia coli | E. coli MG1655 | SpCas9 | λ-Red | ds linear | SNP | 2 | S | 30 |

| insertion, deletion, SNP | 2 | - | 49 | ||||||

| Plasmid | insertion, deletion, SNP | 2 | S | 32 | |||||

| Cas9n | none | None | deletion | 2 | - | 78 | |||

| Cas12a | λ-Red | ss oligo | deletion, SNP | 2 | S | 97 | |||

| ds linear | gene replacement | ||||||||

| E. coli BW25113 | dCas9 | none | None (base editing) | C-T mutations | 1 | - | 7 | ||

| 14 | Enterobacter aerogenes | E. aerogenes IAM1183 | SpCas9 | λ-Red | ds linear | deletion | 2 | - | 93 |

| 15 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | K. pneumoniae KP_1.6366 | Cas9n | none | None (base editing) | C-T mutations | 1 | M, S | 89 |

| SpCas9 | λ-Red | ss oligo | deletion | 2 | |||||

| ds linear | |||||||||

| Plasmid | deletion, insertion | ||||||||

| K. pneumoniae KP_3744 | deletion | ||||||||

| K. pneumoniae KP_5573 | |||||||||

| Cas9n | none | None (base editing) | C-T mutations | 1 | |||||

| 16 | Lactobacillus brevis | Lactobacillus brevis ATCC367 | SpCas9 | RecE/T | Plasmid | deletion | 2 | M, S | 28 |

| 17 | Lactobacillus casei | L. casei LC2W | Cas9n | None | Plasmid | deletion, insertion | 1 | - | 75 |

| 18 | Lactobacillus lactis | L. lactis MG1363 | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | deletion | 2 | - | 84 |

| L. lactis NZ9000 | SpCas9 | RecT | ss oligo | SNP, deletion, insertion | 2 | - | 22 | ||

| 19 | Lactobacillus plantarum | L. plantarum WCFS1 | SpCas9 | RecE/T | ds linear or Plasmid | deletion, insertion | 2 | M, S | 28 |

| RecT | ss oligo | SNP | 2 | M, S | 42 | ||||

| L. plantarum WJL | |||||||||

| None | Plasmid | SNP, deletion | |||||||

| L. plantarum NIZO2877 | |||||||||

| 20 | Lactobacillus reuteri | L. reuteri 6475 | SpCas9 | RecT | ss oligo | SNP | 2 | - | 63 |

| 21 | Methylococcus capsulatus | Methylococcus capsulatus Bath | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | SNP | 2 | - | 81 |

| Cas9n | |||||||||

| 22 | Mycobacterium smegmatis | M. smegmatis mc2155 | Cas12a | None | None (NHEJ) | random | 1 | - | 79 |

| gp60, gp61 | ss oligo | SNP, deletion, insertion | 2 | S | 97 | ||||

| 23 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | P. aeruginosa PAK | SpCas9 | λ-Red | Plasmid | deletion, insertion | 2 | M, S | 3 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | deletion | ||||||||

| ss oligo | |||||||||

| ds linear | |||||||||

| Cas9n | None | None (base editing) | C-T mutations | 1 | |||||

| 24 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | P. fluorescens GcM5–1A | Cas9n | None | None (base editing) | C-T mutations | 1 | M, S | 3 |

| 25 | Pseudomonas putida | P. putida KT2440 | SpCas9 | λ-Red | Plasmid | deletion, insertion, SNP | 2 | - | 80 |

| Redβ | ss oligo | deletion, SNP | 2 | - | 94 | ||||

| Ssr | ss oligo | deletion, SNP | 3 | - | 2 | ||||

| None | Plasmid | deletion | 2 | - | 92 | ||||

| 26 | Pseudomonas syringae | P. syringae DC3000 | Cas9n | None | None (base editing) | C-T mutations | 1 | M, S | 3 |

| 27 | Streptomyces albus | S. albus J1074 | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | deletion | 1 | S | 9 |

| 28 | Streptomyces coelicolor | S. coelicolor A3 | SpCas9 | None | None (NHEJ) | deletion | 1 | M | 83 |

| Plasmid | deletion, SNP | ||||||||

| S. coelicolor M145 | Plasmid | deletion, SNP | S | 26 | |||||

| Cas12a | deletion | M, S | 45 | ||||||

| None (NHEJ) | deletion | ||||||||

| 29 | Streotpmyces lividans | S. lividans 66 | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | deletion | 1 | S | 9 |

| 30 | Streptomyces hygroscopicus | S. hygroscopicus SIPI-KF | Cas12a | None | Plasmid | deletion | 1 | M, S | 45 |

| 31 | Streptomyces pristinaespiralis | S. pristinaespiralis HCCB10218 | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | deletion | 1 | S | 26 |

| 32 | Streptomyces viridochromogenes | S viridochromogenes DSM 40736 | SpCas9 | None | Plasmid | deletion | 1 | S | 9 |

| 33 | Staphylococcus aureus | S. aureus ATCC 29213 | SpCas9 | EF2132 | ss oligo | deletion, SNP | 2 | - | 64 |

| S. aureus RN4220 | None | Plasmid | deletion, insertion, SNP | 1 | S | 6 | |||

| S. aureus Newman | deletion | ||||||||

| S. aureus USA300 | |||||||||

| 34 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | S. pneumoniae crR6 | SpCas9 | None | ds linear | SNP | 0 | S | 30 |

| S. pneumoniae R6_8232.5 | |||||||||

| 35 | Tatumella citrea | T. citrea DSM 13699 | SpCas9 | λ-Red | Plasmid | deletion | 2 | S | 32 |

| 36 | Yersinia pestis | Y. pestis KIM6+ | Cas12a | λ-Red | ss oligo | SNP | 2 | S | 97 |

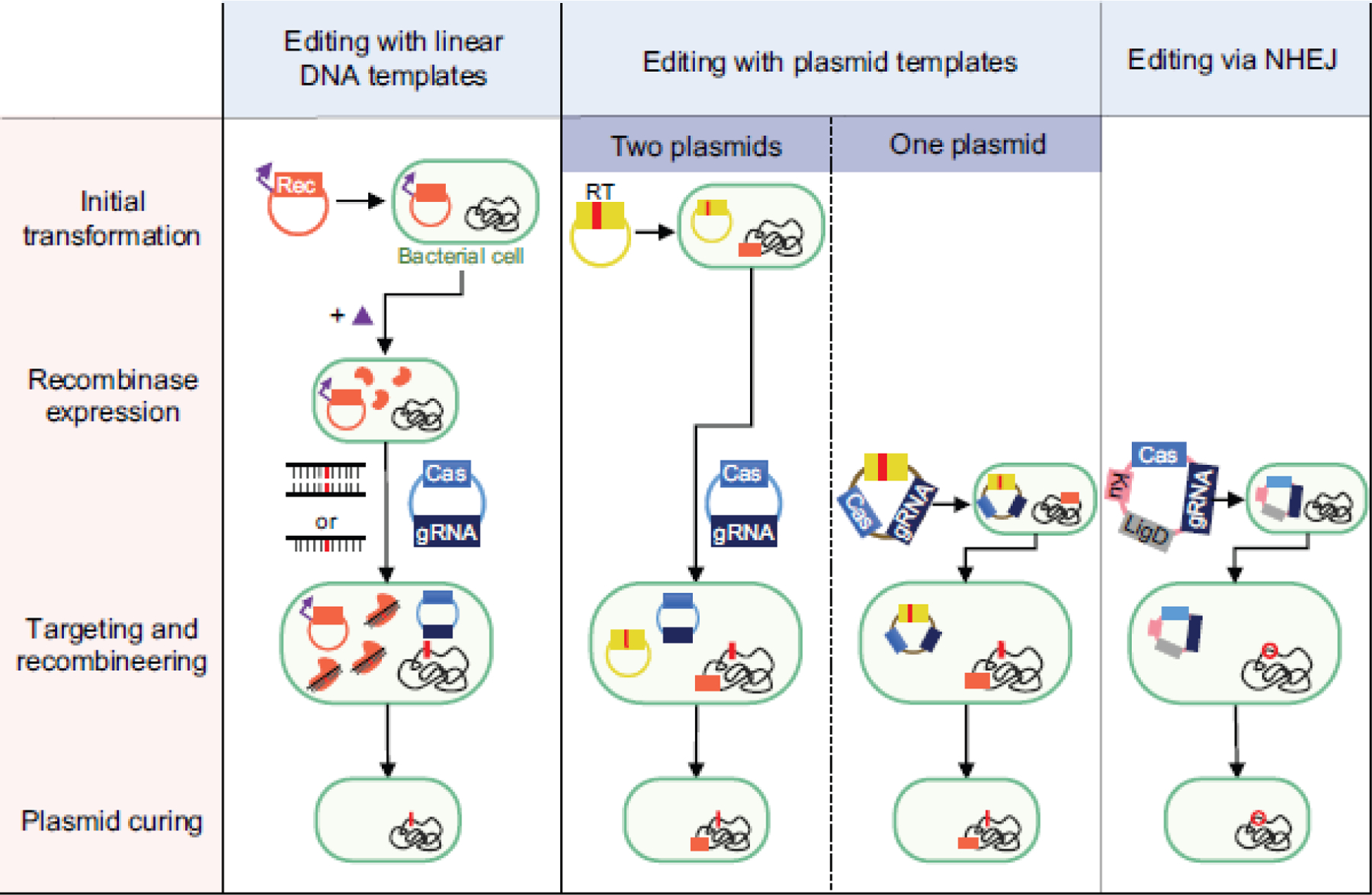

The first strategy uses linear DNA as the recombineering template as well as a phage-derived, heterologous DNA recombinase to drive recombineering before counterselecting with a CRISPR nuclease (Figure 1, Column 1). Briefly, this strategy involves first transforming a plasmid containing the recombinase machinery, then inducing expression of the recombinase, and finally co-transforming the linear DNA template (often a short oligonucleotide but sometimes double-stranded DNA) and plasmid(s) encoding the CRISPR nuclease and targeting gRNA. One key requirement is possessing a heterologous recombinase that yields efficient recombination in the strain of interest. Fortunately, several recombinases are available and have been commonly used in different bacteria. For instance, in the original demonstration of genome editing with SpCas9 in E. coli, the authors used recombinases from the phage-derived λ-Red system to incorporate edits with a linear double-stranded DNA template [30]. Since then, recombination with the λ-Red system has been used to edit other Proteobacteria using linear or double-stranded DNA templates [89, 93, 94, 97], where only the β protein within the λ-Red system is required for recombination [94]. RecT single-stranded DNA recombinases have also been used to incorporate point mutations with high efficiencies in several Gram-positive bacteria [33, 42, 63]. However, these recombinases usually must be derived from related phages, requiring an initial step to identify functional RecT recombinases before attempting CRISPR-based editing. Beyond a functional recombinase, the transformation efficiency of the strain must be sufficiently high to ensure that at least one cell receiving both the linear template and the CRISPR plasmid will undergo successful recombineering. Finally, while CRISPR-based editing with oligonucleotides has been successful for generating point mutations and small deletions, editing efficiencies with this approach have been shown to severely decrease for larger deletions [2] although such larger changes may be more accessible using long single-stranded DNA templates as demonstrated in mammalian cells [10].

Fig. 1. Different strategies for CRISPR-based genome editing in bacteria.

Column 1: Recombineering using a linear DNA template followed by counterselection with CRISPR nucleases. A plasmid encoding a heterologous recombinase (Rec) is introduced into the cell and induced before co-transforming the linear DNA template and CRISPR-nuclease plasmid. Column 2: Recombineering using a plasmid-encoded recombineering template (RT) with or without a heterologous recombinase. The recombineering template can be placed on the plasmid harboring the CRISPR machinery for an all-in-one plasmid system, or it can be placed on a separate plasmid before transforming the CRISPR nuclease/gRNA plasmid. While one-plasmid systems are more streamlined, the larger plasmid could prove harder to transform and co-encoding the nuclease and gRNA could interfere with cloning if the gRNA can target the genome of the cloning strain. If no exogenous recombinase is used, this method relies on the cell’s native recombineering machinery. Column 3: Editing via the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway. Depending on the strain, ku and/or ligD can be encoded on the plasmid harboring the CRISPR machinery and transformed into the strain. All strategies require plasmid curing after recombineering and nuclease targeting to isolate the mutant strain before pursuing downstream applications.

The second strategy uses a plasmid DNA template for recombineering. The template is encoded either on the same plasmid as the CRISPR machinery or on a separate plasmid (Figure 1, Column 2). In either case, heterologous recombinases such as those in the complete λ-Red system have been used to achieve insertions, deletions, and point mutations [32, 80]. However, the cell’s native recombination machinery can also be employed. For instance, genome editing in E. coli with SpCas9 and a plasmid-encoded recombineering template harboring ~1 kb homology arms efficiently generated a point mutation in the lacZ gene without a heterologous recombinase [12]. Instead, editing occurred via the RecA-dependent homologous recombination pathway. Interestingly, a separate study with E. coli reported that a heterologous recombinase was essential when using a plasmid-encoded recombineering template [4], although an entire gene was inserted in this case. Aside from E. coli, several other bacterial species have undergone successful CRISPR-based genome editing with a plasmid-encoded recombineering template but no heterologous recombinase, including members of the genera Bacillus [1], Clostridium [27], Lactobacillus [42, 84], Pseudomonas [92], Streptomyces [26], and Staphylococcus [6]. Relying on the endogenous machinery for homologous recombination simplifies the editing workflow, as it only requires transforming one or two shuttle vectors containing the editing template and CRISPR machinery. However, this machinery may not be available or sufficiently active in some bacteria, requiring the identification and utilization of heterologous recombinases. As homologous recombination of double-stranded DNA requires multiple proteins [11, 61, 95], identifying recombinases which work in every bacterium could prove challenging.

The third strategy for CRISPR-based editing does not use a recombineering template and instead relies on the NHEJ pathway to drive editing upon CRISPR-based cleavage (Figure 1, Column 3). Editing through this strategy therefore avoids challenges associated with using CRISPR for counterselection and could be particularly advantageous when introducing deleterious mutations throughout the genome. In bacteria, the NHEJ pathway depends on two proteins: Ku and LigD. Ku binds the ends of the cleaved DNA and the protein LigD seals the DNA together, often resulting in non-specific mutations, insertions, or deletions (also called indels) [72]. To date, a few groups have achieved CRISPR-based NHEJ using bacteria where both ku and ligD are present and active, where one gene had to be heterologously expressed, or where both genes had to be heterologously expressed. For instance, Sun et. al achieved an indel frequency of up to 70% by transforming a strain of Mycobacterium smegmatis harboring functional copies of both ku and ligD with a plasmid encoding Cas12a from Francisella tularensis (FnCas12a) and a gRNA [79]. Separately, Tong et. al generated various deletions in a strain of Streptomyces coelicolor harboring a functional ku by supplementing the cells with ligD from the closely related Streptomyces carneus [83]. Finally, Li et. al generated small deletions and infrequent large deletions by transforming a different strain of S. coelicolor lacking NHEJ activity with a plasmid containing both ligD and ku as well as FnCas12a and a gRNA [45]. This overall strategy involved transforming only a single plasmid containing CRISPR components and (if required) NHEJ components, even if only smaller, random deletions can be generated. We do note, however, that only a quarter of prokaryotes are estimated to encode Ku proteins [58]. Furthermore, overexpressing ligD and ku can be cytotoxic in bacteria [45] and could lead to off-target mutations due to repair of spontaneous double-stranded DNA breaks. Finally, expressing these genes may not yield successful indel formation, as Cui and Bikard reported that expressing ku and ligD from M. tuberculosis in the E. coli genome did not rescue cells from Cas9-induced cleavage [12]. In general, more studies attempting this strategy are necessary to realize its full potential for genome editing.

Reports of CRISPR-based genome editing typically include a single strategy to create a few edits in a single strain. In contrast, few studies used one strategy across multiple strains, and even fewer compared multiple strategies at one time (Table 1). As one of these few examples, Jiang et. al showed that an oligo-based strategy with a RecT recombinase and FnCas12a could efficiently introduce point mutations in several strains of Corynebacterium glutanicum, but the efficiency of ssDNA recombineering plummeted for larger deletions [33]. Based on this limitation, the authors developed an all-in-one plasmid system containing FnCas12a, the gRNA, and a recombineering template that achieved up to a 7.5-kb deletion and a 1-kb insertion at low efficiencies (10% and 5%, respectively). Separately, Leenay et. al provided (to our knowledge) the only example to compare strategies across multiple strains, using three strains of Lactobacillus plantarum and two separate editing strategies: one using an oligonucleotide recombineering template and a RecT recombinase, and another using a plasmid-encoded recombineering template and the endogenous recombination machinery [42]. The authors found that the oligo-based editing method was far more efficient when generating a point mutation in rpoB, while the plasmid-based editing method was far more efficient when inserting a premature stop codon in ribB. However, for both methods, the success of genome editing was strain-specific. For instance, oligo-mediated recombineering with RecT yielded no colonies, 9% edited colonies, or 100% edited colonies across the three tested strains, while plasmid-based editing yielded colonies only with the intended mutation, creating a premature stop codon, for one strain or colonies only with an unintended ~1.3kb deletion for another strain. Therefore, within the diversity of editing strategies that have been developed in bacteria, no prevailing method currently exists and the ideal method instead likely depends on the desired edit, the target location, and the strain.

Cytotoxicity and lack of colonies with SpCas9 has motivated alternatives to achieve efficient editing.

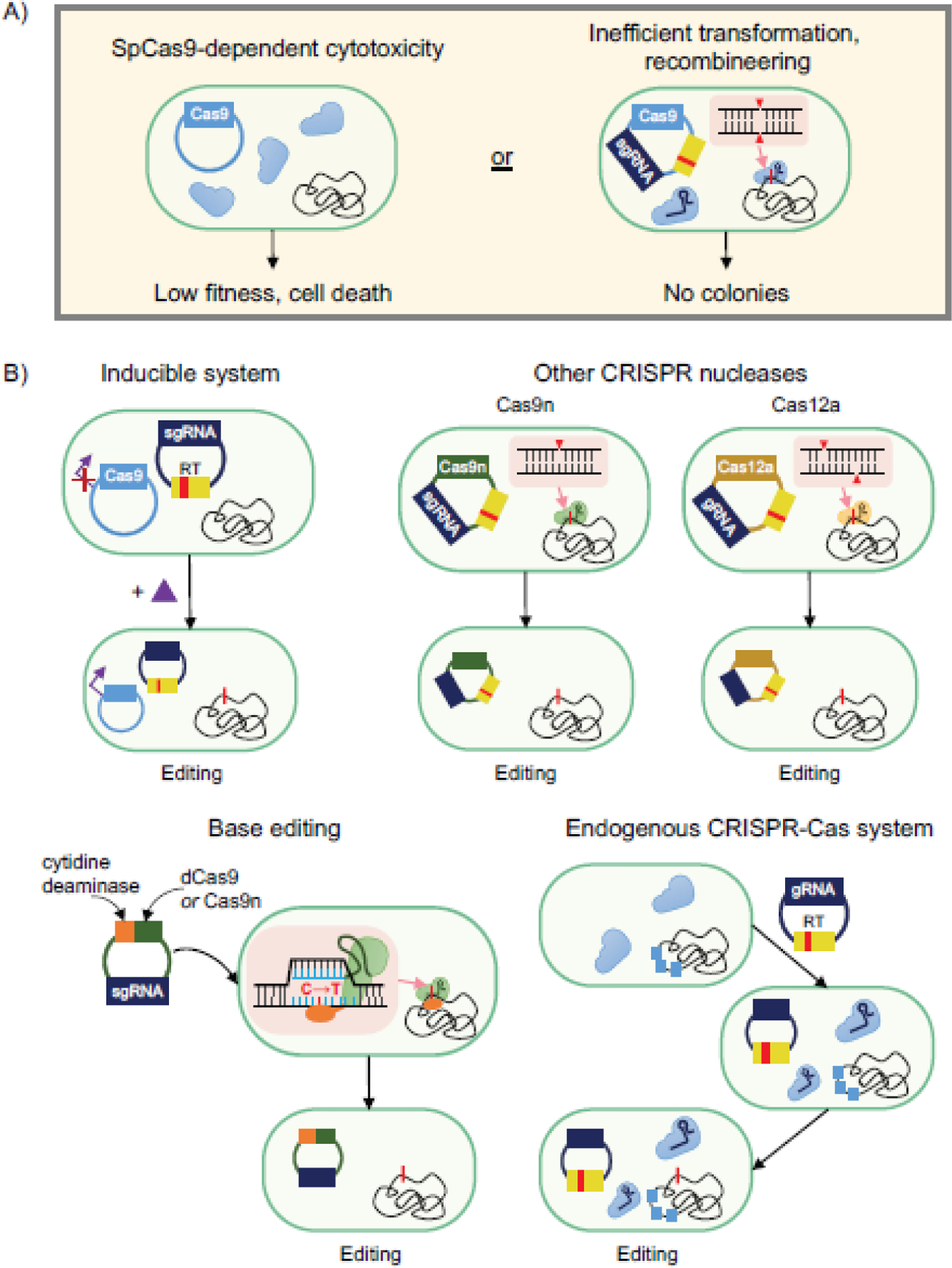

Since the original studies demonstrating programmable DNA cleavage and genome editing in E. coli with SpCas9 [30, 34], this nuclease has been used almost exclusively to perform editing in other bacteria. This trend can be attributed in part to SpCas9 representing one of the first well-characterized single-effector nucleases as well as its relatively simple PAM requirements and its robust expression in many different organisms. However, overexpressing SpCas9 in bacteria can be cytotoxic, posing a potential barrier to its widespread use for genome editing (Figure 2A). One study revealed that overexpressing a catalytically dead version of SpCas9 (dCas9) in E. coli induced abnormal morphology and decreased growth rates, suggesting that SpCas9-cytotoxicity is not solely due to DNA cleavage [8] and instead possibly relates to transient PAM recognition and subsequent DNA binding across the genome. Another study in Corynebacterium glutamicum reported that transforming a plasmid expressing SpCas9 without a gRNA failed to produce any colonies even in the absence of recombination machinery, suggesting that SpCas9 can be cytotoxic on its own [33]. Finally, while multiple studies have reported instances in which SpCas9 can be tolerated in the bacterial cell, genome targeting greatly reduced the number of surviving cells even in the presence of a recombineering template [46, 75, 96]. For bacteria associated with poor transformation efficiencies or weakly active recombinases, this effect can result in no colonies following introduction of SpCas9 and a targeting gRNA. Future studies should aim to elucidate and circumvent the general mechanism(s) of SpCas9 cytotoxicity in bacteria to broadly enhance the use this nuclease for genome editing.

Fig. 2. Circumventing lack of colonies when using SpCas9 in bacteria.

a) Expressing SpCas9 is cytotoxic in some bacteria (left), while other bacteria do not yield any colonies when attempting editing (right). b) Several alternative strategies can be explored to circumvent these issues. Upper left: Utilizing inducible systems to express SpCas9 following transformation and culturing. Via an inducible promoter, SpCas9 expression is strongly repressed without inducer present and only induced after culturing the cells to ensure a large number of cells possess all components necessary for editing. Upper right: Using less toxic nucleases to achieve editing. Cas9n, which only cleaves one strand of DNA, and Cas12a can be less toxic than SpCas9. Lower left: SpCas9-derived base editors eliminate the need to create a double-stranded break to achieve editing. A translational fusion of dCas9 or Cas9n, a cytidine deaminase domain, and a uracil DNA glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) is introduced on a plasmid into the cell. Upon nuclease binding and R-loop formation, cytidines on the non-target strand within a defined window adjacent to the PAM are rapidly converted to uracils. Lower right: Harnessing endogenous CRISPR nucleases for genome editing. For strains harboring native CRISPR nucleases, gRNAs can be introduced along with a recombineering template to achieve editing without expressing a heterologous CRISPR nuclease. One drawback is that native cRNAs can compete with the introduced genome-targeting gRNAs, although preventing crRNA biogenesis can eliminate this barrier.

Utilizing inducible systems for SpCas9 expression represents one of the earliest attempted workarounds (Figure 2B, upper left). In the first example in E. coli, Reisch and Prather used inducible expression of a destabilized and sub-optimally expressed version of SpCas9 to ensure no targeting-dependent lethality in the absence of inducer [67]. Using Bacillus subtilis, Altenbuchner placed a mannose-inducible promoter upstream of the SpCas9 gene to minimize nuclease targeting before the transformed cells were plated on mannose-supplemented agar [1]. In a separate study in Clostridium acetobutylicum, Wasels et. al determined that constitutively expressing SpCas9 failed to produce surviving colonies in the presence of an engineered single-guide RNA (sgRNA) and recombineering template, whereas placing SpCas9 expression under the control of an anhydrotetracycline-inducible promoter resulted in efficient editing [91]. Despite the success of these studies, leaky expression of toxic nucleases could still prevent editing. Therefore, a more elaborate approach used a light-inducible system for CRISPR nuclease expression [103, 65, 62], although these systems have yet to be demonstrated in bacteria. Finally, Mougiakos et. al achieved editing in the thermophile Bacillus smithii by demonstrating that SpCas9 is inactive above 42°C. By delivering an all-in-one plasmid containing SpCas9, an sgRNA, and homology arms, they were able to induce recombineering at higher temperatures before allowing CRISPR selection for edited cells at 37°C [60]. This temperature-inducible approach to genome editing is relevant to bacteria that grow at the elevated temperature but can survive at the lower temperature, although the discovery of CRISPR nucleases with other temperature dependencies [55, 56, 82] could expand this approach to other bacteria.

Using other nucleases instead of wild-type SpCas9 has also been explored to reduce toxicity and obtain edited colonies (Figure 2B, upper right). Mutating one catalytic residue in SpCas9 produces a variant that only cuts one strand of DNA [34]. This “nicking” Cas9 (Cas9n) has been able to achieve genome editing in cases where SpCas9 failed to produce any colonies, likely due to reduced cytotoxicity. In one study, Standage-Beier et. al demonstrated that by transforming a plasmid containing Cas9n and an sgRNA targeting a region between two repeat sequences, 36-kb and 97-kb deletions from the genome were obtained [78]. Genome editing with Cas9n was further exploited in several bacteria [44, 46, 75, 96], where it has proven particularly useful for generating large genomic deletions [44, 78] and for achieving plasmid-based recombineering with shorter homology arms than the typical 1 kb used with Cas9 [46, 96]. However, it has been demonstrated that the reduced lethality of Cas9n may lead to less efficient or a complete lack of editing, especially without sufficient expression of the Cas9n nuclease [57, 75]. More work is therefore needed to understand the mechanistic basis of genome editing with Cas9n and how editing can be further enhanced.

Another alternative to SpCas9 is using the Type V-A Cas12a CRISPR nuclease. These nucleases possess inherent differences compared to Cas9 such as recognizing a T-rich PAM or introducing a 5’ 5-nt overhang upon DNA cleavage [100]. Cas12a nucleases also tend to be smaller than most Cas9’s and are able to process a transcribed CRISPR array into individual crRNAs without any accessory factors. While these differences do not automatically enhance genome editing, Jiang et. al revealed an instance in Corynebacterium glutamicum where a plasmid expressing either SpCas9 or SpCas9n were both unable to transform cells, while a Cas12a nuclease derived from Francisella novicida (FnCas12a) could be successfully transformed and yielded efficient editing [33]. Since then, Cas12a has been used both with and without a heterologous recombinase to achieve high-efficiency deletions, insertions, and mutations in several other bacteria [24, 45, 97]. Taken together, Cas12a represents a promising means of achieving CRISPR-based editing in bacteria, although more studies are needed to more fully understand its advantages and limitations.

A recently-introduced alternative for genome editing involves modified CRISPR nucleases called base editors (Figure 2B, bottom left). Base editors typically comprise translational fusions of dCas9 or Cas9n and a cytidine deaminase domain, and convert cytidines to uracils on the non-target strand in a defined window adjacent to the PAM [38]. Although not completely necessary, fusing a uracil DNA glycosylase inhibitor to the base editor has been shown to improve editing efficiencies by inhibiting uracil removal upon editing [3, 37]. Because no double-stranded breaks are introduced, the cytotoxicity of DNA targeting should be greatly lessened [7]. To date, base editors have been principally employed in bacteria to generate point mutations or insert premature stop codons, with published demonstrations in E. coli [3], P. aeruginosa [7], K. pneumoniae [89], and C. beijerinckii [47]. The workflow is simple as it only requires transforming a single plasmid containing the modified CRISPR nuclease and a gRNA. Base editors typically utilize the nicking version of Cas9 to drive alterations of the uncleaved strand [37, 47]. However, one study reported poor transformation efficiency for the Cas9n base editor [3], and switching to dCas9 reduced cytotoxicity and was able to achieve multiplexed editing [3]. We also note that this base-editing plasmid can be extremely cytotoxic and mutagenic in our hands, especially during cloning (unpublished results). Thus, more work is needed to advance the use of these unique editors in bacteria.

A final strategy to overcome a lack of colonies when using SpCas9 is to utilize a host’s endogenous CRISPR system (Figure 2B, bottom right). It has been estimated that up to half of bacteria contain endogenous CRISPR-Cas systems [21], and re-purposing these systems may enable efficient selection without the need to express a heterologous CRISPR nuclease [23]. Initially, endogenous Type I CRISPR systems were used for gene repression by inactivating effector nuclease Cas3 and delivering self-targeting guides [53]. More recently, they have been utilized to achieve genome editing in several Clostridia [66, 101]. One potential bottleneck is that endogenous crRNAs can completely outcompete heterologously expressed gRNAs, as was shown when attempting gene repression utilizing an endogenous Type I-B CRISPR system in the archaeon Haloferax volcanii [76]. To overcome this issue, the authors deleted the cas6b gene responsible for generating endogenous crRNAs, resulting in efficient gene repression and editing in this microbe [76, 77]. To fully utilize an endogenous system for genome editing, it must be sufficiently characterized, including identifying PAMs and ensuring that the cas genes are actively expressed. While characterizing endogenous CRISPR-Cas systems can be time consuming, utilizing them for subsequent genome editing could potentially reduce cytotoxicity and simplify the editing process by excluding a heterologous CRISPR nuclease. Overall, several alternatives to editing exist in instances where SpCas9 fails to generate colonies, yet each alternative requires further development to improve its widespread application.

Cells can escape CRISPR-based editing, and identifying escape mechanisms can facilitate enhanced editing.

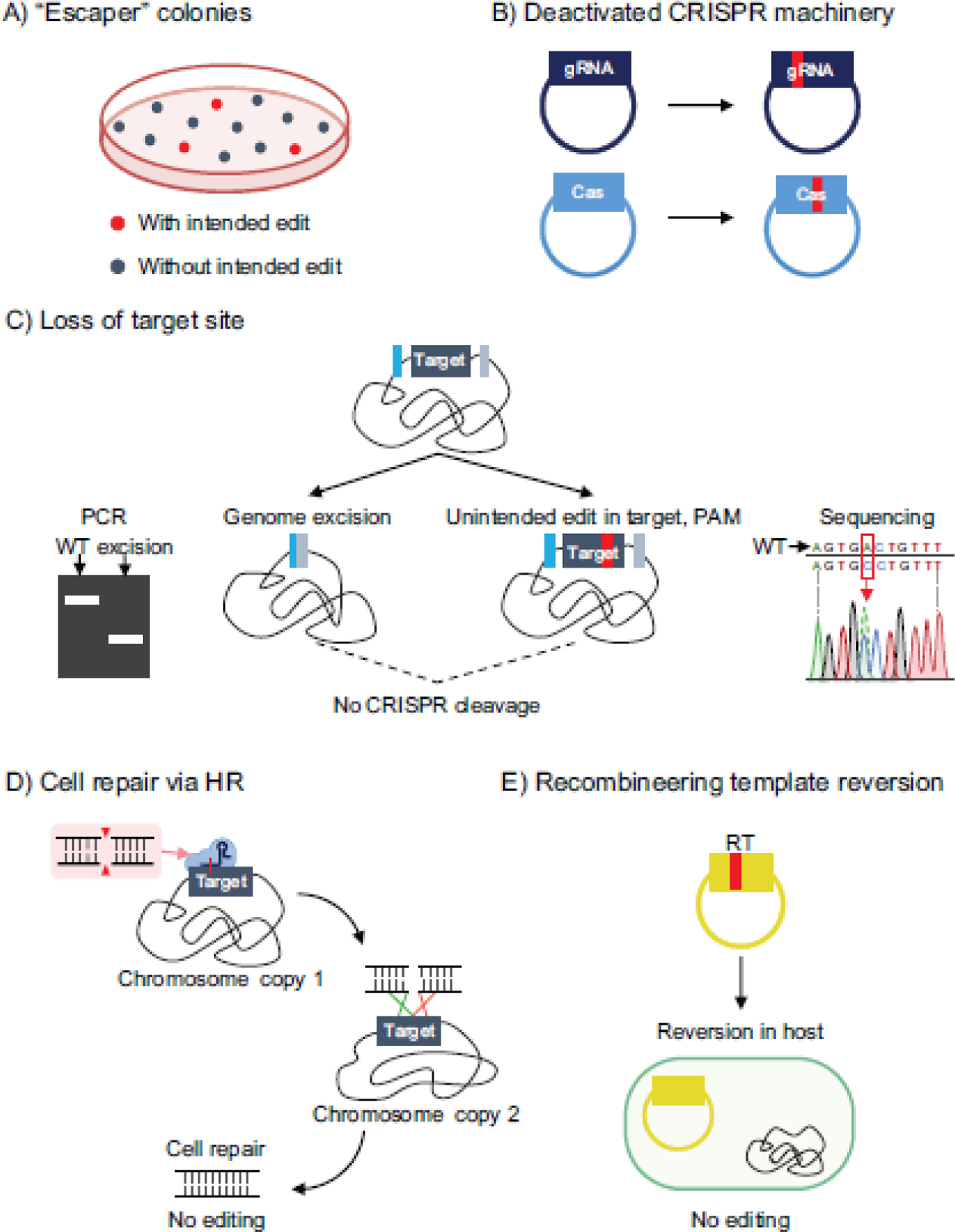

After performing targeting and recombineering transformations, there are often surviving colonies that either contain the wild-type sequence or an unintended edit, making isolation of cells containing the desired edit difficult (Figure 3A). These colonies are often referred to as “escaper colonies.” As most bacteria lack an active NHEJ pathway, they must find another way of avoiding or surviving CRISPR cleavage. Identifying these failure modes could provide insights toward circumventing escape and enhancing editing. However, the mechanisms underlying escaper colonies have been rarely investigated. This section underscores the need to report failure modes and develop workarounds to reduce escapers and improve genome-editing efficiencies across bacteria.

Fig. 3. Reported failure modes of CRISPR-based genome editing in bacteria.

a) Escaper colonies can form that contain either the wild-type sequence or an unintended edit, and make screening for correctly edited cells more difficult. b) Deactivated CRISPR machinery. Bacteria sometimes avoid CRISPR cleavage by mutating the gRNA on the transformed plasmid or mutating the cas genes. c) Unintended genomic excision events and mutations result in loss of target sequence. Bacteria can remove the protospacer sequence targeted by the CRISPR nuclease via genomic excision events driven by homologous recombination with the genome or via mutations to the protospacer. d) Cell repair via homologous recombination with the genome. Upon CRISPR cleavage at the target site, the cell can use another copy of the chromosome to repair itself. e) Reversion of the recombineering template. The recombineering template containing the desired mutation can revert back to the wild-type sequence in the host cell, preventing editing.

Perhaps the most commonly observed reason for escaper colonies is via the bacterium deactivating the CRISPR machinery, by mutating either the nuclease domain or the spacer (Figure 3B). Multiple studies have reported instances where surviving colonies either contained mutations in or completely lost the gRNA targeting sequence on the transformed plasmid, the latter of which could occur through recombination between the outside repeats when using CRISPR arrays to express gRNAs [20, 99]. Furthermore, one study characterizing a type I-B CRISPR system in Haloferax isolated 30 escaper colonies after transforming a self-targeting guide and reported that 77% contained mutations or deletions within the cas gene cluster [18].

In other cases, the cell can modify its genome to disrupt or eliminate the target site, thereby preventing genome targeting by accumulating unintended mutations at the target site (Figure 3C). While inadvertent small mutations in the target sequence are possible (see section NHEJ above), genomic modifications resulting from CRISPR-based genome targeting in bacteria are predominantly large deletions. For instance, Vercoe et. al expressed a gRNA utilized by the native type I-F CRISPR system of Pectobacterium atrosepticum to target a pathogenicity island, resulting in excision of the entire ~98-kb HAI2 island [85]. Other studies have reported genomic excision events when targeting the genome with Cas9 that arise due to recombination between direct repeats or homologous insertion sequences [12, 71, 78]. While these excision events technically are genomic edits and could be useful in some applications [71], such excision events can also represent a significant barrier to achieving a prescribed edit. For instance, Leenay et. al reported the occurrence of a persistent 1.3-kb deletion, including the target sequence, in one strain of L. plantarum when attempting to insert a premature stop codon in the ribB gene using a plasmid-encoded recombineering template [42]. Therefore, unintended edits that remove the target site represent another mode of failure for CRISPR-based genome editing in bacteria.

Another reported mechanism of escape from CRISPR-mediated cleavage is by continuous cell repair via homologous recombination with a sister chromosome (Figure 3D). Cui and Bikard demonstrated that homologous recombination via RecA was able to rescue cells from targeting with different spacers, and thus by deleting the recA gene or inhibiting RecA with the GamS protein from Mu phage, the authors were able to improve counter-selection with Cas9 [12]. Furthermore, Moreb et. al demonstrated that transiently inhibiting RecA could improve gRNA targeting and CRISPR selection on a genome-wide scale, and they used this approach to significantly boost oligo-mediated genome editing efficiencies in E. coli [59]. This study also demonstrated that inhibiting RecA reduces the SOS response of cells, particularly the activity of the error-prone umuDC polymerase, which could be the source of mutations in the guide sequence or those that deactivate Cas9 [59, 73].

Finally, Leenay et. al reported a unique failure mode when attempting editing of the rpoB gene in L. plantarum using a plasmid-encoded recombineering template (Figure 3E). They found that the desired point mutation within the recombineering template reverted to the wild-type sequence inside the host before introducing the SpCas9 plasmid [42]. Interestingly, this failure mode led to an increase in the number of unedited escaper colonies compared to that of a control without a recombineering template. While this observation is likely the result of homologous recombination between the multi-copy plasmid and the chromosome, a more systematic approach (e.g curing the recombineering-template plasmid prior to SpCas9 transformation) is needed to elucidate the mechanism of this failure mode.

Optimizing the expression of the CRISPR nuclease and/or gRNA has proven able to overcome modes of escape in several instances. For example, Sun et. al compared multiple Cas9 and Cas12a variants in targeting M. smegmatis and revealed fewer escaper colonies for FnCas12a than for two Cas9 variants, which the authors attribute to higher measured transcript levels for FnCas12a [79]. Li et. al also optimized the strength of their constitutive promoter for Cas12a expression and increased killing efficiency from 41.5% to nearly 100% [45]. Likewise, using stronger promoters upstream of the gRNA have been demonstrated to improve counterselection in multiple instances [75, 94]. Aside from optimizing promoter strength, placing the CRISPR machinery on a high-copy number plasmid has also been shown to decrease the number of escapers [22]. Finally, codon optimizing the CRISPR and recombineering machinery for the strain of interest can increase editing efficiency [47]. However, more systematic analyses are required to determine the optimal CRISPR nuclease expression level to maximize counter selection while avoiding cytotoxicity. In total, bacteria possess multiple mechanisms of surviving CRISPR-based targeting, underscoring the need to identify and circumvent escape modes to increase genome-editing efficiency across strains.

Future Perspectives.

Genome editing of industrial bacteria remains critical for strain engineering, and several methods for CRISPR-based genome editing have been implemented in a handful of species. However, many unknowns associated with CRISPR-based editing have slowed achievement of CRISPR-based editing in more diverse, non-model strains. This review has focused on several significant barriers to editing that must be elucidated to render a more predictable editing process. Moving forward, several avenues of research should be pursued to enhance CRISPR-based genome editing and help deliver this important tool to a wider range of industrial bacteria.

First, the strategies described above possess distinct limitations and have exhibited varying success based on the strain, intended edit, and target site. As a result, no single approach currently can achieve efficient editing across all strains, and testing multiple editing strategies in parallel represents the most dependable approach when attempting editing in a new strain or for a new desired edit. In the future, in-depth studies are needed that directly compare multiple strategies using similar types of edits across multiple strains. In turn, these studies could elucidate advantages and limitations of each strategy and provide general rules on when to adopt one strategy versus another. In time, these insights could provide a level of predictability that has so far eluded the implementation of many CRISPR-based tools in bacteria.

Second, future studies should focus on directly elucidating and countering how editing fails. Instances of failed editing are present in most demonstrations of CRISPR-based editing; however, these examples are often noted only in passing. We instead hold that these instances should be the starting point for in-depth studies to determine the underlying mechanisms. Critically, the resulting insights can be directly translated into countermeasures that boost editing efficiencies. Efforts that systematically identify and counteract these failure modes would be particularly valuable by providing general trends that can aid others seeking to rapidly boost editing efficiencies. Separately, DNA repair pathways are intimately connected with genome editing with CRISPR in bacteria and thus represent a separate avenue for further exploration [70]. For instance, inhibiting RecA-dependent homologous repair in E. coli was demonstrated to boost counterselection and editing [59], representing an example of how hijacking host’s DNA repair mechanisms can actually improve editing. Therefore, future studies should aim to characterize DNA repair pathways and their interplay with CRISPR-based cleavage. To start, NHEJ pathways are beginning to be utilized to generate random edits, although native NHEJ pathways could also reduce efficiencies for precise edits. Characterizing more ku and ligD variants in bacteria will boost our understanding of these important DNA repair pathways and should drive enhanced workarounds to improve editing. Ultimately, this research should work towards enabling high-efficiency recombineering to drive genome editing.

A third potential avenue involves interrogating the expanding set of CRISPR nucleases beyond the canonical SpCas9. First, SpCas9 is just one of many Cas9 nucleases that can be exploited for editing. One study in particular directly compared Cas9 variants from different bacteria in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, finding that the highest gene repression was achieved not with SpCas9 but a Cas9 derived from Streptococcus thermophilus [68]. Second, many additional nuclease types and sub-types are being discovered that could offer more efficient or robust editing in different bacteria. For instance, a diverse set of type V CRISPR nucleases were recently discovered outside of Cas12a that offer varying domain architectures and catalytic activities [98]. Third, there are increasing efforts to engineer CRISPR nucleases to enhance their overall properties [25, 36]. While these efforts have principally centered on engineering variants with broadened PAM recognition or reduced off-targeting, CRISPR nucleases could be similarly engineered to specifically enhance editing in bacteria (e.g. variants that are less cytotoxic or drive editing through homologous recombination or other repair pathways without killing the cell). Finally, characterizing more endogenous CRISPR nucleases represents a simple and powerful alternative to current strategies of CRISPR-based editing that should be considered in strains harboring native CRISPR-Cas systems. While this strategy is unlikely to be universal given that not all bacteria possess endogenous CRISPR-Cas systems, the presence of an endogenous system should represent a starting point when developing CRISPR-based tools.

As the set of discovered CRISPR nucleases continues to expand, further research is necessary to improve the predictability of target selection for efficient genome editing in bacteria. Even for the well-studied SpCas9, it is often reported that different gRNAs produce different efficiencies of editing or gene regulation in bacteria, yet the mechanism for this observation is rarely explored. For instance, in one study, Bikard et. al performed a high-throughput screen in E. coli using dCas9 and reported unexpected strong fitness defects for certain gRNAs even when targeting non-essential genes [13]. Through machine learning, they realized that several distinct 5-nt seed sequences produced added dCas9-cytotoxicity that could be reduced by decreasing the expression of dCas9. In a more recent study, Zhang et. al improved upon previous genome-editing efficiencies with FnCas12a in C. glutamicum by optimizing the selected PAM sequence as well as the length of the spacer sequence [102].

Finally, we must acknowledge that several important technical capabilities must be in place before CRISPR can be implemented for genome editing. At a minimum, each bacterium must be culturable, transformable, and possess a set of defined selectable plasmids and expression constructs, and unfortunately generalizable means to achieve each of these remain underdeveloped [86]. Further, the transformation efficiency in the strain-of-interest has to be sufficiently high to enable delivery of both CRISPR components and recombineering machinery. Particularly for poorly transformable strains, recombineering efficiency must be maximized while CRISPR nuclease cytotoxicity must be minimized to achieve editing. To this end, finding more highly efficient recombinases as well as tunable promoters in the strain-of-interest should improve editing attempts. Taken together, several important future avenues of research should help overcome several critical barriers to CRISPR-based genome editing in order to systematically deliver this important tool to a wider range of industrial bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (MCB-1452902 to C.L.B.), the National Institutes of Health (5T32GM008776 to J.M.V.) and start-up funds from NCSU (to N.C.C.). We also gratefully acknowledge Jie Sun for assistance with figure preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altenbuchner J (2016) Editing of the Bacillus subtilis Genome by the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:5421–5427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aparicio T, de Lorenzo V, Martínez-García E (2018) CRISPR/Cas9-based counterselection boosts recombineering efficiency in Pseudomonas putida. Biotechnol J 13:e1700161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banno S, Nishida K, Arazoe T, et al. (2018) Deaminase-mediated multiplex genome editing in Escherichia coli. Nat Microbiol 3:423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassalo MC, Garst AD, Halweg-Edwards AL, et al. (2016) Rapid and efficient one-step metabolic pathway integration in E. coli. ACS Synth Biol 5:561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Börner RA, Kandasamy V, Axelsen AM, et al. (2019) Genome editing of lactic acid bacteria: opportunities for food, feed, pharma and biotech. FEMS Microbiol Lett 366: 10.1093/femsle/fny291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W, Zhang Y, Yeo W-S, et al. (2017) Rapid and efficient genome editing in Staphylococcus aureus by using an engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system. J Am Chem Soc 139:3790–3795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, et al. (2018) CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and cytidine deaminase-mediated base editing in Pseudomonas species. iScience 6:222–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho S, Choe D, Lee E, et al. (2018) High-level dCas9 expression induces abnormal cell morphology in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth Biol 7:1085–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobb RE, Wang Y, Zhao H (2015) High-efficiency multiplex genome editing of Streptomyces species using an engineered CRISPR/Cas system. ACS Synth Biol 4:723–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Codner GF, Mianné J, Caulder A, et al. (2018) Application of long single-stranded DNA donors in genome editing: generation and validation of mouse mutants. BMC Biol 16:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Court DL, Sawitzke JA, Thomason LC (2002) Genetic engineering using homologous recombination. Annu Rev Genet 36:361–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui L, Bikard D (2016) Consequences of Cas9 cleavage in the chromosome of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 44:4243–4251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui L, Vigouroux A, Rousset F, et al. (2018) A CRISPRi screen in E. coli reveals sequence-specific toxicity of dCas9. Nature Communications 9:1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis KN (1990) Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gramnegative eubacteria. J Bacteriol 172:6568–6572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deltcheva E, Chylinski K, Sharma CM, et al. (2011) CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature 471:602–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Mali P, et al. (2013) Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res 41:4336–4343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donohoue PD, Barrangou R, May AP (2018) Advances in industrial biotechnology using CRISPR-Cas systems. Trends Biotechnol 36:134–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer S, Maier L-K, Stoll B, et al. (2012) An archaeal immune system can detect multiple protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs) to target invader DNA. J Biol Chem 287:33351–33363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V (2012) Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:E2579–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomaa AA, Klumpe HE, Luo ML, et al. (2014) Programmable removal of bacterial strains by use of genome-targeting CRISPR-Cas systems. MBio 5:e00928–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C (2007) The CRISPRdb database and tools to display CRISPRs and to generate dictionaries of spacers and repeats. BMC Bioinformatics 8:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo T, Xin Y, Zhang Y, et al. (2019) A rapid and versatile tool for genomic engineering in Lactococcus lactis. Microb Cell Fact 18:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Goh YJ, Barrangou R (2019) Characterization and repurposing of type I and type II CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria. J Mol Biol 431:21–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong W, Zhang J, Cui G, et al. (2018) Multiplexed CRISPR-Cpf1-mediated genome editing in Clostridium difficile toward the understanding of pathogenesis of C. difficile infection. ACS Synth Biol 7:1588–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu JH, Miller SM, Geurts MH, et al. (2018) Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 556:57–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang H, Zheng G, Jiang W, et al. (2015) One-step high-efficiency CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in Streptomyces. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin 47:231–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H, Chai C, Li N, et al. (2016) CRISPR/Cas9-based efficient genome editing in Clostridium ljungdahlii, an autotrophic gas-fermenting bacterium. ACS Synth Biol 5:1355–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang H, Song X, Yang S (2019) Development of a RecE/T-assisted CRISPR-Cas9 toolbox for Lactobacillus. Biotechnol J e1800690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang F, Doudna JA (2017) CRISPR-Cas9 structures and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biophys 46:505–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang W, Bikard D, Cox D, et al. (2013) RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Biotechnol 31:233–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang W, Zhou H, Bi H, et al. (2013) Demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA-mediated targeted gene modification in Arabidopsis, tobacco, sorghum and rice. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e188–e188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Y, Chen B, Duan C, et al. (2015) Multigene editing in the Escherichia coli genome via the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:2506–2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang Y, Qian F, Yang J, et al. (2017) CRISPR-Cpf1 assisted genome editing of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Nat Commun 8:15179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, et al. (2012) A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337:816–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaboli S, Babazada H (2018) CRISPR mediated genome engineering and its application in industry. Curr Issues Mol Biol 26:81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleinstiver BP, Pattanayak V, Prew MS, et al. (2016) High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 529:490–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, et al. (2016) Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 533:420–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komor AC, Badran AH, Liu DR (2017) Editing the genome without double-stranded DNA breaks. ACS Chem Biol 13:383–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Zhang F (2017) Diversity, classification and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Curr Opin Microbiol 37:67–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurtz CB, Millet YA, Puurunen MK, et al. (2019) An engineered E. coli Nissle improves hyperammonemia and survival in mice and shows dose-dependent exposure in healthy humans. Sci Transl Med 11:eaau7975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leenay RT, Beisel CL (2017) Deciphering, communicating, and engineering the CRISPR PAM. J Mol Biol 429:177–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leenay RT, Vento JM, Shah M, et al. (2019) Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9 in Lactobacillus plantarum revealed that editing outcomes can vary across strains and between methods. Biotechnol J 14:e1700583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Shen CR, Huang C-H, et al. (2016) CRISPR-Cas9 for the genome engineering of cyanobacteria and succinate production. Metab Eng 38:293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li K, Cai D, Wang Z, et al. (2018) Development of an efficient genome editing tool in Bacillus licheniformis using CRISPR-Cas9 nickase. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02608–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li L, Wei K, Zheng G, et al. (2018) CRISPR-Cpf1-assisted multiplex genome editing and transcriptional repression in Streptomyces. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e00827–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Q, Chen J, Minton NP, et al. (2016) CRISPR-based genome editing and expression control systems in Clostridium acetobutylicum and Clostridium beijerinckii. Biotechnol J 11:961–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Q, Seys FM, Minton NP, et al. (2019) CRISPR-Cas9D10A nickase-assisted base editing in solvent producer Clostridium beijerinckii. Biotechnol Bioeng 116:1475–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li X-T, Thomason LC, Sawitzke JA, et al. (2013) Positive and negative selection using the tetA-sacB cassette: recombineering and P1 transduction in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y, Lin Z, Huang C, et al. (2015) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing. Metab Eng 31:13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang L, Liu R, Garst AD, et al. (2017) CRISPR EnAbled trackable genome engineering for isopropanol production in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng 41:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin J-L, Wagner JM, Alper HS (2017) Enabling tools for high-throughput detection of metabolites: Metabolic engineering and directed evolution applications. Biotechnol Adv 35:950–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu P, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG (2003) A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res 13:476–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo ML, Mullis AS, Leenay RT, Beisel CL (2015) Repurposing endogenous Type I CRISPR-Cas systems for programmable gene repression. Nucleic Acids Res 43:674–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, et al. (2013) RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339:823–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malzahn AA, Tang X, Lee K, et al. (2019) Application of CRISPR-Cas12a temperature sensitivity for improved genome editing in rice, maize, and Arabidopsis. BMC Biol 17:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marshall R, Maxwell CS, Collins SP, et al. (2018) Rapid and scalable characterization of CRISPR technologies using an E. coli cell-free transcription-translation system. Mol Cell 69:146–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McAllister KN, Bouillaut L, Kahn JN, et al. (2017) Using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing to generate C. difficile mutants defective in selenoproteins synthesis. Sci Rep 7:14672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McGovern S, Baconnais S, Roblin P, et al. (2016) C-terminal region of bacterial Ku controls DNA bridging, DNA threading and recruitment of DNA ligase D for double strand breaks repair. Nucleic Acids Res 44:4785–4806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moreb EA, Hoover B, Yaseen A, et al. (2017) Managing the SOS response for enhanced CRISPR-Cas-based recombineering in E. coli through transient inhibition of host RecA activity. ACS Synth Biol 6:2209–2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mougiakos I, Bosma EF, Weenink K, et al. (2017) Efficient genome editing of a facultative thermophile using mesophilic spCas9. ACS Synth Biol 6:849–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murphy KC (1998) Use of bacteriophage lambda recombination functions to promote gene replacement in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 180:2063–2071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nihongaki Y, Otabe T, Sato M (2018) Emerging approaches for spatiotemporal control of targeted genome with inducible CRISPR-Cas9. Anal Chem 90:429–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oh J-H, van Pijkeren J-P (2014) CRISPR-Cas9-assisted recombineering in Lactobacillus reuteri. Nucleic Acids Res 42:e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Penewit K, Holmes EA, McLean K, et al. (2018) Efficient and scalable precision genome editing in Staphylococcus aureus through conditional recombineering and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated counterselection. MBio 9:e00067–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Polstein LR, Gersbach CA (2015) A light-inducible CRISPR-Cas9 system for control of endogenous gene activation. Nat Chem Biol 11:198–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pyne ME, Bruder MR, Moo-Young M, et al. (2016) Harnessing heterologous and endogenous CRISPR-Cas machineries for efficient markerless genome editing in Clostridium. Sci Rep 6:25666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reisch CR, Prather KLJ (2015) The no-SCAR (Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering) system for genome editing in Escherichia coli. Sci Rep 5:15096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rock JM, Hopkins FF, Chavez A, et al. (2017) Programmable transcriptional repression in mycobacteria using an orthogonal CRISPR interference platform. Nat Microbiol 2:16274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ronda C, Pedersen LE, Sommer MOA, Nielsen AT (2016) CRMAGE: CRISPR optimized MAGE recombineering. Sci Rep 6:19452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Selle K, Barrangou R (2015) Harnessing CRISPR-Cas systems for bacterial genome editing. Trends in Microbiology 23:225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Selle K, Klaenhammer TR, Barrangou R (2015) CRISPR-based screening of genomic island excision events in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:8076–8081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shuman S, Glickman MS (2007) Bacterial DNA repair by non-homologous end joining. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:852–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith BT, Walker GC (1998) Mutagenesis and more: umuDC and the Escherichia coli SOS response. Genetics 148:1599–1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.So Y, Park S-Y, Park E-H, et al. (2017) A highly efficient CRISPR-Cas9-mediated large genomic deletion in Bacillus subtilis. Front Microbiol 8: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Song X, Huang H, Xiong Z, et al. (2017) CRISPR-Cas9 nickase-assisted genome editing in Lactobacillus casei. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e01259–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stachler A-E, Marchfelder A (2016) Gene repression in Haloarchaea using the CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats)-Cas I-B system. J Biol Chem 291:15226–15242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stachler A-E, Turgeman-Grott I, Shtifman-Segal E, et al. (2017) High tolerance to self-targeting of the genome by the endogenous CRISPR-Cas system in an archaeon. Nucleic Acids Res 45:5208–5216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Standage-Beier K, Zhang Q, Wang X (2015) Targeted large-scale deletion of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-nickases. ACS Synth Biol 4:1217–1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun B, Yang J, Yang S, et al. (2018) A CRISPR-Cpf1-assisted non-homologous end joining genome editing system of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Biotechnol J 13:e1700588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sun J, Wang Q, Jiang Y, et al. (2018) Genome editing and transcriptional repression in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 via the type II CRISPR system. Microb Cell Fact 17:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tapscott T, Guarnieri MT, Henard CA (2019) Development of a CRISPR/Cas9 system for Methylococcus capsulatus in vivo gene editing. Applied and Environmental Microbiology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Teng F, Cui T, Feng G, et al. (2018) Repurposing CRISPR-Cas12b for mammalian genome engineering. Cell Discov 4:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tong Y, Charusanti P, Zhang L, et al. (2015) CRISPR-Cas9 based engineering of Actinomycetal genomes. ACS Synth Biol 4:1020–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van der Els S, James JK, Kleerebezem M, Bron PA (2018) Versatile Cas9-driven subpopulation selection toolbox for Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02752–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vercoe RB, Chang JT, Dy RL, et al. (2013) Cytotoxic chromosomal targeting by CRISPR/Cas systems can reshape bacterial genomes and expel or remodel pathogenicity islands. PLoS Genet 9:e1003454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Waller MC, Bober JR, Nair NU, Beisel CL (2017) Toward a genetic tool development pipeline for host-associated bacteria. Current Opinion in Microbiology 38:156–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang S, Dong S, Wang P, et al. (2017) Genome editing in Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum N1–4 with the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e00233–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang S, Hong W, Dong S, et al. (2018) Genome engineering of Clostridium difficile using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Clin Microbiol Infect 24:1095–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang Y, Wang S, Chen W, et al. (2018) CRISPR-Cas9 and CRISPR-assisted cytidine deaminase enable precise and efficient genome editing in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e01834–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Warming S, Costantino N, Court DL, et al. (2005) Simple and highly efficient BAC recombineering using galK selection. Nucleic Acids Res 33:e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wasels F, Jean-Marie J, Collas F, et al. (2017) A two-plasmid inducible CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing tool for Clostridium acetobutylicum. J Microbiol Methods 140:5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wirth NT, Kozaeva E, Nikel PI (2019) Accelerated genome engineering of Pseudomonas putida by I-SceI-mediated recombination and CRISPR-Cas9 counterselection. Microb Biotechnol. 10.1111/1751-7915.13396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu Y, Hao Y, Wei X, et al. (2017) Impairment of NADH dehydrogenase and regulation of anaerobic metabolism by the small RNA RyhB and NadE for improved biohydrogen production in Enterobacter aerogenes. Biotechnol Biofuels 10:248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wu Z, Chen Z, Gao X, et al. (2019) Combination of ssDNA recombineering and CRISPR-Cas9 for Pseudomonas putida KT2440 genome editing. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 10.1007/s00253-019-09654-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xin Y, Guo T, Mu Y, Kong J (2017) Identification and functional analysis of potential prophage-derived recombinases for genome editing in Lactobacillus casei. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364:fnx243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xu T, Li Y, Shi Z, et al. (2015) Efficient genome editing in Clostridium cellulolyticum via CRISPR-Cas9 nickase. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:4423–4431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yan M-Y, Yan H-Q, Ren G-X, et al. (2017) CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted recombineering in bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e00947–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yan WX, Hunnewell P, Alfonse LE, et al. (2019) Functionally diverse type V CRISPR-Cas systems. Science 363:88–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zerbini F, Zanella I, Fraccascia D, et al. (2017) Large scale validation of an efficient CRISPR/Cas-based multi gene editing protocol in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact 16:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, et al. (2015) Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 163:759–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang J, Zong W, Hong W, et al. (2018) Exploiting endogenous CRISPR-Cas system for multiplex genome editing in Clostridium tyrobutyricum and engineer the strain for high-level butanol production. Metab Eng 47:49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang J, Yang F, Yang Y, et al. (2019) Optimizing a CRISPR-Cpf1-based genome engineering system for Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb Cell Fact 18:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhou XX, Zou X, Chung HK, et al. (2018) A single-chain photoswitchable CRISPR-Cas9 architecture for light-inducible gene editing and transcription. ACS Chem Biol 13:443–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]