Highlights

-

•

COVID-19 pandemic crisis is dramatically changing all aspects of human interactions, including social trust.

-

•

With unique panel data collected amid the COVID-19 in South Korea, we examined changes in social trust toward various social institutions.

-

•

Trust in society, people, and the government improved, whereas trust in judicature, the press, and religious organizations decreased.

-

•

Improvement in trust was associated with proactive responses to the pandemic crisis, and failure to do so resulted in the deteriorating trust.

-

•

This study contributes to the understanding of relations between risk management and social trust with the COVID-19 situation in South Korea.

Keywords: COVID-19, Social trust, Risk management, South Korea

Abstract

This study aims to exploit the situations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic crisis in South Korea to identify the causal effect of a pandemic crisis and institutional responses on social trust. With unique panel data collected in the course of the COVID-19 in South Korea and the use of individual fixed-effects models, we examined how social trust in various social institutions changed and identified a causal effect of crisis management on social trust. According to the results, trust in South Korean society, people, and the central and local governments improved substantially, whereas trust in judicature, the press, and religious organizations sharply decreased. Improvement in trust in the central and local governments was associated with proactive responses to the pandemic crisis, and failure to take appropriate actions was responsible for the deteriorating trust in religious organizations. These findings illustrate the importance of risk management in trust formation and imply that South Korea may be transforming from a low-trust to a high-trust society.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19, hereafter) were reported in China in late 2019. Since then, COVID-19 has spread around the world and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in early 2020. Governments worldwide promptly took preventive measures against the new virus, and other social and public institutions, such as the press, civic groups, and religious organizations, have also played critical roles in this time of demographic crisis, caused by the worldwide spread of the virus.

In this study, we examined the change in people’s attitudes, namely, the level of social trust in those institutions in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, based on the experience of South Korea (Korea, hereafter). Social trust, a belief in the competence, honesty, or benevolence of the other party (McKnight & Chervany, 2000), is known as a crucial cause and consequence of functioning institutions (Van de Walle & Bouckaert, 2003). Thus, the formation and dissolution of social trust have been of primary interest both for analysts and leaders, and many existing literatures have examined the trends, causes, and consequences of social trust and its relationship with institutional effectiveness (Coleman, 1990; Dalton, 2007; Delhey & Newton, 2005; Fukuyama, 1995; Knack & Keefer, 1997; Moy & Scheufele, 2000; Putnam, 2000).

Studies on social trust have identified 4 major drivers of trust in institutions: culture, institutional setting, economic and social outcomes, and performance of institutions (OECD, 2013). The relationship between institutional performance and trust has been of particular interest to the leaders of organizations because the role of trust has increasingly been identified as the potentially missing element for better crisis management and performance (Győrffy, 2018; James & Wooten, 2010). What is less known, however, is 1) whether effective crisis management could increase the level of institutional trust, particularly in the course of a crisis, and 2) the causal direction between crisis management and trust (Knack, 2002; Van de Walle & Bouckaert, 2003). To the extent that the level of trust in institutions affects both the survival of the organization at the time of crisis and the speed and magnitude of the post-crisis recovery, it is crucial to increase, or at least maintain, the level of trust in the institution by using effective crisis management (James & Wooten, 2010; Nakagawa & Shaw, 2004). Without trust in the government or institutions, support for policy implementation is difficult to mobilize, particularly where short-term sacrifices are demanded but long-term gains are less feasible, for example, in crisis situations (OECD, 2013). Yet the causal relationship between institutional performance and trust is not firmly established; thus, literature has discussed the causal flows from both directions. Because the data requirements to answer these research questions are demanding, accumulating empirical findings and evidence to answer them has been challenging.

In this vein, the COVID-19 experience of Korea since early 2020 provides a unique venue to empirically test the questions on the changes in social trust during a crisis. As of May 2020, COVID-19 is still ongoing in Korea, but both the Korean government and public health authorities believe that the situation is primarily under control and expect to resume everyday life in the near future. Although deemed successful in hindsight, the prevention and containment efforts made by various social institutions, particularly the government, was constantly under suspicion and criticized over the course of the pandemic crisis. Since Korea is known for its low level of trust in public institutions such as the government, the judicial system, and the press (Lee, 1998, 2006; OECD, 2013), the government had to fight against the viruses as well as the public’s suspicion and cynicism from the very beginning.

With a unique dataset collected in the course of COVID-19 in Korea, we demonstrate that the public’s level of trust in various social institutions could substantially change according to their performance in crisis management, and we also identify a causal direction from the performance to the level of social trust. We also investigate the covariates of the changes in the trust and provide potential mechanisms that explain the relationship. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to deepen outside Korea, we aimed to provide empirical evidence of the impact of the institutional (mis-)management during the crisis that could have led to an increased or decreased level of trust toward the institution.

2. Data and methods

We used the Korean Academic Multimode Open Survey (KAMOS) to achieve the goals presented in Section 1. The KAMOS is a nationally representative sample survey conducted annually since 2016. The KAMOS uses 2 modes of data collection: an initial face-to-face household interview and follow-up online surveys. Household surveys were conducted in the spring, and the sample size was 1500 to 2000 per year. Online surveys were administered to the respondents of household surveys once or twice in the same year, and the sample size was approximately 1,000. Hence, the KAMOS is basically a repeated cross-sectional data but has longitudinal features within 1 year.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the operation of baseline household surveys in 2020 because face-to-face household interviews became virtually prohibited during the “Social Distancing Campaign.” Instead of postponing survey operations until the situation stabilized, the KAMOS conducted online surveys by contacting 8500 individuals interviewed in previous years (2016–2019). The online survey was conducted between March 24 and April 25 in 2020, and the response rate was 11.9 % (N = 1011). The low response raised concerns of the representativeness of the 2020 sample, but we justified the use of the 2020 KAMOS data combined with the previous data on the following grounds. First, the cautious analysis of any available information is worthwhile given the swiping influences of pandemic crisis, despite concerns of the representativeness of data. Second, we used longitudinal features of the 2020 KAMOS. By comparing responses before and during or after the pandemic crisis, we identified the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis on social trust.

We analyzed 10 social trust measures (Table 1 ). Each was measured on a 10-point scale, and a higher value meant higher trust. Using these items, we conducted the following analyses. First, we examined how the level of trust in each domain changed over time by using the entire 2016–2020 KAMOS data to demonstrate the general trend in social trust. Next, we examined within-individual changes in social trust before and during or after the crisis to estimate the effect of the pandemic crisis on social trust. In other words, we estimated individual fixed-effects models that control for observed and unobserved confounders to obtain causal estimates. Finally, we examined how the changes in social trust differed by gender, age, education, occupation, income, subjective class, housing ownership, political ideology, and marital status. Political ideology was measured using 5-point scale with higher values meaning more conservative ideology, and age was measured at 1-year intervals. Other variables were dichotomized as described in Table 2 .

Table 1.

Social trust in South Korea (10-point scale).

| Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Korean society | 5.49 | 5.38 | 5.44 | 5.35 | 6.18 |

| Korean people | 5.74 | 5.64 | 5.71 | 5.57 | 6.05 |

| Central government | 4.81 | 5.08 | 5.05 | 4.73 | 5.71 |

| Local government | 5.07 | 5.23 | 4.98 | 4.84 | 5.45 |

| Congress | 3.82 | 4.06 | 3.66 | 3.21 | 3.37 |

| Judicature | 5.09 | 4.90 | 4.82 | 4.44 | 3.95 |

| Private company | 5.28 | 5.37 | 5.16 | 4.88 | 4.85 |

| Press | 5.04 | 5.09 | 4.83 | 4.36 | 3.75 |

| Civic group | 5.46 | 5.48 | 5.24 | 4.73 | 4.63 |

| Religious organization | 5.25 | 5.44 | 4.80 | 4.62 | 2.89 |

| N | 2000 | 2000 | 2010 | 1500 | 1011 |

Table 2.

Correlates for changes in trust (N = 908)a.

| Outcomes |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Korean society | Korean people | Central gov't. | Local gov't. | Congress | Judicature | Private company | Press | Civic group | Relig. Org. |

| Female | −0.069 | −0.044 | −0.122 | −0.073 | 0.237 | −0.063 | −0.348 | 0.085 | 0.183 | −0.056 |

| Age | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.020 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.029 | 0.021 |

| College educated | 0.156 | 0.054 | 0.140 | −0.095 | 0.010 | −0.331 | −0.125 | −0.225 | −0.284 | −0.081 |

| Professional/Managerial | 0.592 | 0.076 | −0.174 | 0.203 | 0.047 | 0.257 | 0.015 | 0.154 | −0.193 | 0.636 |

| Household Income> = 4 million won | 0.092 | 0.178 | −0.058 | 0.094 | −0.063 | 0.007 | −0.067 | 0.023 | 0.228 | 0.043 |

| Subjectively upper- middle class | −0.667 | −0.393 | −0.387 | −0.208 | −0.451 | −0.150 | −0.140 | −0.095 | −0.308 | −0.217 |

| Own house | −0.109 | −0.142 | −0.385 | −0.569 | −0.205 | −0.201 | −0.361 | −0.277 | −0.488 | −0.611 |

| Political ideologyb | −0.478 | −0.257 | −0.486 | −0.380 | −0.148 | −0.062 | −0.209 | −0.113 | −0.104 | −0.029 |

| Never married | −0.244 | −0.145 | −0.275 | −0.227 | −0.339 | −0.432 | −0.420 | −0.508 | −0.070 | −0.355 |

Coefficients with p-value smaller than 0.05 are marked as bold.

Political ideology was measured using 5-point scale with higher values meaning more conservative ideology.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analysis

Table 1 shows how social trust in Korea has changed since 2016. Until 2019, social trust continued deteriorating in all domains. This pattern is consistent with the literature on low generalized trust in Korea (Lee, 2006). However, the pattern diverged in 2020. Although social trust sharply improved in some domains (Korean society, the Korean people, the central government, and the local government), the deterioration accelerated in others (judicature, the press, and religious organizations). The central government and religious organizations experienced the most dramatic change. Although trust in the central government improved by 1.0 points, trust in religious organizations decreased by 1.7 points.

Diverging changes in trust that depend on domains in 2020 should be related to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. The central government’s responses to the pandemic were controversial in the early stage but later gained public support. The Korean government, different from many other countries, did not close the international borders. This policy was heavily attacked by the mass media and opposition party as confirmed COVID-19 cases suddenly increased starting in mid-February. As the domestic situations stabilized in late March, which was in sharp contrast with scary situations in Europe and the United States, positive perceptions prevailed. This dramatic change was also associated with the declining trust in the press that had criticized the government’s initial actions. By contrast, the dramatic decrease in trust in religious organizations is likely to be associated with role in pseudo-religious group New Heaven and Earth (Shin Chun Ji) in the COVID-19 outbreak in mid-February and refusal of some conservative Christian factions to cancel Sunday services. The community-level infection outbreak occurred at a congregational meeting of New Heaven and Earth groups, leading to a negative perception of this group in particular and religion in general. Some conservative Christian churches continued having Sunday congregational service despite the governmental request for substituting online services to reduce the risk of infections because of person-to-person contact. This refusal invoked severe criticisms. Hence, evaluations of the responses of the government and religious groups to this pandemic crisis should be responsible for changes in social trust in these domains.

The trends of social trust presented in Table 1 suggest that the pattern of social trust underwent critical changes in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis; however, sample selection, instead of the pandemic crisis and the responses to it, could be responsible for this change. We found counterevidence against this concern. First, the trend of social trust in each domain was almost identical with that reported in Table 1 after controlling for gender, age, education, occupation, household income, subjective class, marital status, and house ownership status (results are not shown). This finding strongly suggests that the selectivity of the 2020 online sample is not the main reason for a dramatic change in social trust in 2020. Second, analyses of changes within individuals yielded consistent patterns reported in Table 1, which we discuss in section 3.2.

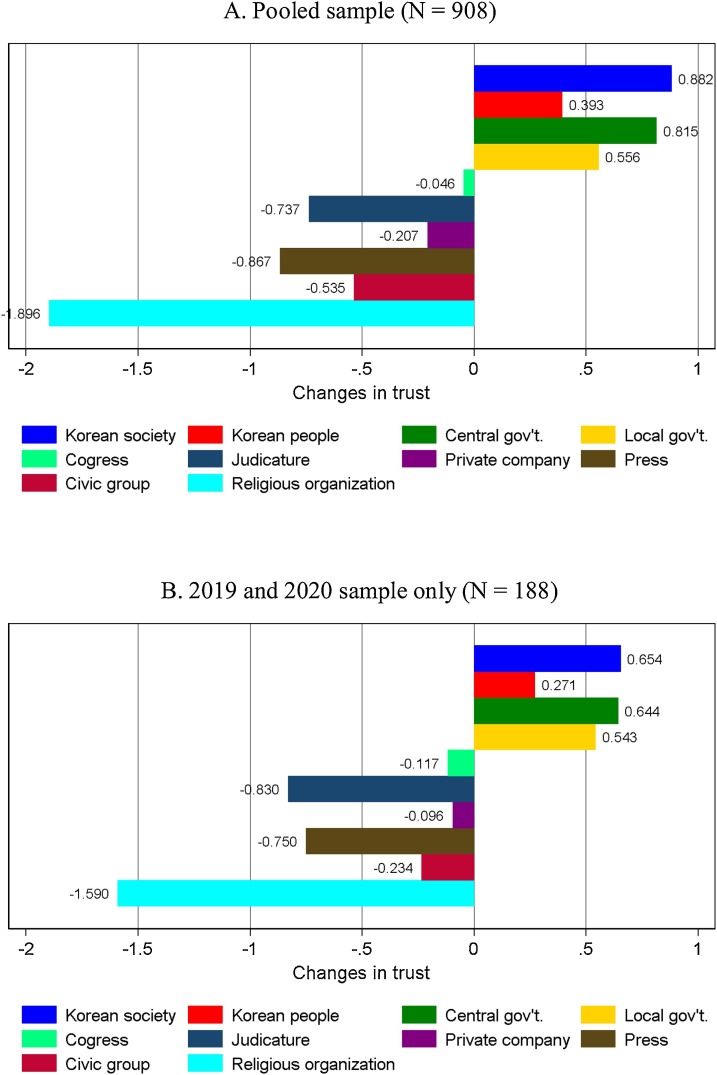

3.2. Changes within individuals

Fig. 1 A presents average within-individual changes in trust in each domain among the respondents interviewed both before and during or after the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Because this analysis used variations in social trust within individuals measured before and during or after the crisis, the estimates can be interpreted as causal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis on social trust. Hence, we can conclude that the crisis and institutional responses substantially increased trust in Korean society and the central government and reduced trust in mass media and religious organizations. This interpretation might be problematic if there were some other changes other than the pandemic crisis affecting social trust in Korea during the observation period. To address this issue, we analyzed the changes in trust by using the 2019 and the 2020 data only (Fig. 1B). The pattern is almost identical, although changes in some domains lost statistical significance because of the small sample size. If social changes other than the COVID-19 pandemic crisis had been primarily responsible for the changing social trust reported in Fig. 1A, B would have different patterns. Hence, we can conclude that the pandemic crisis and the responses to it indeed affected social trust in Korea.

Fig. 1.

Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis on social trust in South Korea.

A. Pooled sample (N = 908)

* The change in trust in congress is not statistically significant.

B. 2019 and 2020 sample only (N = 188)

* The changes in the trust in Korean people, congress, private companies, and civic groups are not statistically significant.

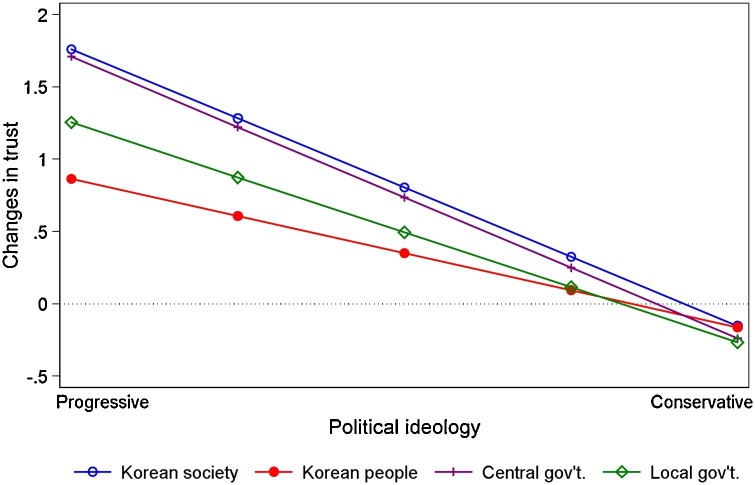

3.3. Differential changes within individuals

Table 2 shows the correlates of trust change. Subjective class and political ideology were observed to moderate the effect of the crisis on trust. Changes in trust in Korean society and people among respondents who regarded themselves as middle class or higher were less positive than those who self-identified as lower class. This finding suggests that generalized trust improved more among the lower class than among the upper class. The most noteworthy contrast was observed regarding political ideology. The conservatives experienced a less positive change in trust in Korean society, the Korean people, the central government, and the local government than did the progressives. Fig. 2 presents the predicted changes in trust in these 4 domains. In these 4 domains, the very progressives’ trust increased approximately 1–2 points. However, the very conservatives experienced even negative changes. This finding suggests that responses to the pandemic crisis bifurcated depending on political ideology although the general trend was positive.

Fig. 2.

Differential effect of COVID-19 pandemic crisis effects on social trust on the basis of political ideology.

4. Summary and discussion

The analysis of the KAMOS demonstrated that social trust in Korea changed dramatically in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Although social trust deteriorated in all domains until 2019, the patterns diverged in 2020. Although trust in Korean society, people, and the central and local governments improved substantially, trust in judicature, the press, and religious organizations sharply decreased. The analysis of changes in trust within individuals confirmed this diverging trend. Using the longitudinal nature of the KAMOS, we identified a causal direction from the institutional performance to the level of social trust. We concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic crisis and institutional responses affected social trust in Korea. Notably, this positive effect of the crisis on trust was greater among the politically progressive than on the conservatives, bifurcating social trust in Korea. We admit that events other than the COVID-19 crisis might be responsible for this change. The observed changes would also reflect a temporary positive evaluation of the government’s crisis management at the time of data collection. Nonetheless, the consistent evidence in our analysis suggests that in Korea, the COVID-19 crisis and responses to this indeed had positive effects on generalized social trust but negative effects on some institutions such as religious organizations.

We examined an aspect of the consequences of a demographic crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Although studies of pandemic crises have mostly demonstrated negative effects, our analysis demonstrated that implications of pandemic crises depend on the responses to the crises. For example, the 1918 influenza caused enormous immediate death tolls worldwide and had long-term health consequences for individuals exposed in utero (Almond, 2006). By contrast, we demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic crisis had mixed impacts on social trust, illustrating the importance of risk management in the formation of social trust. Although the improvement in trust in the central and local governments is associated with the proactive responses to the pandemic crisis, the deteriorating trust in religious organizations is a consequence of their dogmatic approach to the crisis and the involvement of a pseudo religious group in the outbreak of a pandemic. The positive impact of the pandemic crisis on generalized social trust in Korea also has an important implication. It provides an opportunity to transform Korea into a high-trust society in the long run. Of course, this transition depends on many contingent factors; however, positive momentum was certainly created during the pandemic crisis. Improvement in generalized social trust may also have a positive feedback to the risk management process because low social trust can exacerbate the consequences of the crisis (Klinenberg, 2015). These 2 topics, the long-term trend of social trust and the feedback between social trust and risk management in Korea and elsewhere, are noteworthy research agendas for post COVID-19 society.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciated the Center for Asian Public Opinion Research & Collaboration Initiative at Chungnam National University for data provision. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A5A2A03068895).

Contributor Information

Bongoh Kye, Email: bkye@kookmin.ac.kr.

Sun-Jae Hwang, Email: sunjaeh@gmail.com.

References

- Almond D. Is the 1918 influenza pandemic over? Long-term effects of in utero influenza exposure in the post-1940 U.S. Population. The Journal of Political Economy. 2006;114(4):672–712. doi: 10.1086/507154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1990. Foundations of social theory. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton R.J. The social transformation of trust in government. International Review of Sociology. 2007;15(1):133–154. doi: 10.1080/03906700500038819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delhey J., Newton K. Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: global pattern or Nordic exceptionalism? European Sociological Review. 2005;21(4):311–327. doi: 10.1093/esr/jci022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama F. Free Press; New York: 1995. Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. [Google Scholar]

- Győrffy D. Palgrave Macmillan; 2018. Trust and crisis management in the European Union: An institutionalist account of success and failure in program countries. [Google Scholar]

- James E.H., Wooten L.P. Routledge; New York: 2010. Leading under pressure: From surviving to thriving before, during, and after a crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Klinenberg E. second edition. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2015. Heat wave: A social autopsy of disaster in Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Knack S. Social capital and the quality of government: Evidence from the States. American Journal of Political Science. 2002;46(4):772–785. doi: 10.2307/3088433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knack S., Keefer P. Does social capital have an economic payoff?: A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1997;112(4):1251–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Democracy, social capital, and social trust. Gyegan Sasang. 1998;37:65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Trust and civil society: Comparative study of Korea and America. Korean Journal of Sociology. 2006;40(5):61–98. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight D.H., Chervany N.L. What is trust? A conceptual analysis and an interdisciplinary model. AMCIS 2000 Proceedings. 2000 382. [Google Scholar]

- Moy P., Scheufele D.A. Media effects on political and social trust. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 2000;77(4):744–759. doi: 10.1177/107769900007700403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y., Shaw R. Social capital: A missing link to disaster recovery. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters. 2004;22(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . OECD. Government at a glance 2013. OECD Publishing; Paris: 2013. Trust in government, policy effectiveness and the governance agenda; pp. 19–37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R. Simon & Schuster; New York: 2000. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Walle S., Bouckaert G. Public service performance and trust in government: The problem of causality. International Journal of Public Administration. 2003;29(8&9):891–913. doi: 10.1081/PAD-120019352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]