Telehealth or telemedicine, defined as “the use of communications technologies to provide and support health care at a distance,” has become an important part of medical care during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1 , 2 In response to the emergent need to reduce the spread of COVID-19 by limiting physical contact, Medicare’s 1135 Waiver lifted previous limits on patient location, range of providers, and the requirement for patients to reside in designated rural areas or for patients to have established provider relationships to receive medical services through telemedicine. Additionally, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services increased reimbursement for telephone visits on par with video.3

However, given limited telemedicine use pre–COVID-19,4 data on clinician and patient attitudes outside of rural and research settings are lacking. We describe a real-world experience of patient- and clinician-rated acceptability of telephone and video outpatient visits during the initial 4 weeks of the emergency COVID-19 response at a large, diverse gastroenterology (GI)/hepatology practice in an academic health system.

Methods

Our study was approved with an expedited review by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board. We surveyed patients aged ≥18 years who received video or telephone visits in 4 outpatient GI/hepatology practices from March 16 to April 10, 2020. As part of standard of care, the health system encouraged patients to enroll in an online portal to enable provider communication and facilitate the downloading of the technology to enable video visits.

Within 3 to 5 days of completing their telemedicine visits, patients were invited to complete a brief survey adapted from prior literature assessing their experiences.5 This was sent automatically via the patient portal using an online survey or via telephone call with study staff for those with no portal access. Using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied), patients were asked to rate telemedicine ease of use, quality of care received, and overall level of satisfaction with the visits. Patients were asked to compare their telemedicine experience to a face-to-face medical visit, comment on likelihood of future use, and indicate whether they would recommend the service to others (net promoter score). Clinicians (physicians and advanced practice providers) answered similar questions regarding ease of use and quality of visits and care provided.

Patient variables included sociodemographics, type of visit (video vs telephone), and use of the online portal as a measure of digital literacy. Clinician characteristics included provider type (physician or advanced practice provider, age, sex, and years of clinical practice experience). Open-ended feedback regarding the telemedicine experience was obtained from patients and clinicians.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Bivariate comparisons were conducted with χ2 tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests where appropriate. Logistic regression models examined factors associated with video telemedicine.

Results

During the study period, 1718 patients had GI/hepatology visits; of these, 104 (6%) were in person and 1614 (94%) were via telemedicine. By contrast, only 54 of 1177 (5%) visits were conducted via telemedicine in the 2 weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic response. Mean patient age was 60 years (SD, 16 years); 59% were women, 20% were Black, 64% White, and 16% other/unknown. In this early period, 27% of visits were conducted via video and 72% via telephone. In week 1, 7% of telemedicine visits were via video; this increased to 47% by week 4. After adjusting for study week and demographics, Black race (odds ratio, 2.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.6-4.2) and age ≥60 years (odds ratio, 1.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-2.7) were independently associated with having telephone vs video visits. There were notable racial and age differences in online portal use, with 87% portal use among Whites vs 39% of Blacks and 77% among age <60 years vs 48% among age ≥60 years (P < .0001).

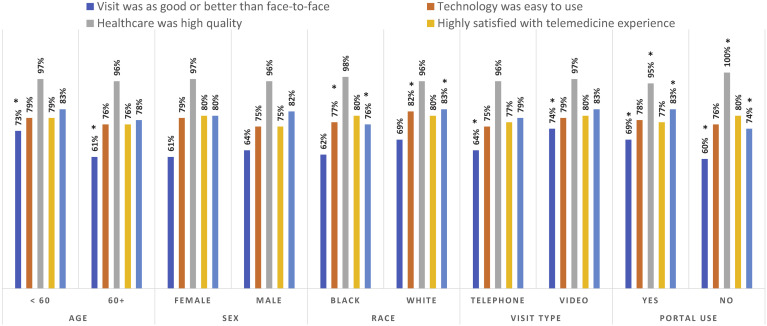

Survey response was 582 (42%) among patients via an online portal and 206 (64%) among those with no portal. Figure 1 shows 2-category responses by notable patient and visit characteristics. A total of 67% rated the telemedicine visit quality “as good/better” than face-to-face, 78% thought technology was easy to use, 96% reported being somewhat/very satisfied with medical care, 78% were somewhat/very satisfied with overall quality of the telemedicine experience, and 80% reported probable/definite future telemedicine use if available. Significant differences in satisfaction were noted by age (older patients less likely to rate telemedicine as good/better than face-to-face), visit method (74% said video was as good/better than face-to-face compared with 64% with telephone), and race (Black patients were less likely to be satisfied with ease of technology use or to report probable/definite future use; P<.0001). Detailed patient survey responses stratified by demographic variables are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 1.

Patient perceptions of telemedicine during the first 4 weeks of COVID-19. Age ≥60 years, telephone visits, and patients with no portal use were less likely to rate visit as good/better than face-to-face. Black patients were less likely to be satisfied with ease of technology or report probable/definite future telemedicine use. Telephone visits were less likely to be rated as good/better than face-to-face. Patients with no portal use less likely to rate visit as good/better than face-to-face, rate care as high quality, or report probable/definite future telemedicine use. ∗P < .05 in bivariate comparisons.

Clinician response was 82% (63 of 77 eligible responded). Clinician responses stratified by years in practice (<20 vs ≥20 years) are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. A total of 88% of clinicians rated video visits as better/as good as face-to-face; this was 41% for telephone. Greater than 80% were somewhat/very satisfied with the care they provided and with conducting telemedicine.

Top patient and clinician concerns were the “lack of physical exam.” Clinicians had concerns about privacy, workflow, and technology. Patients were concerned about fees/charges, privacy, and technology. In general, patients felt the telemedicine experience was “convenient, informative, good, easy, efficient, great, helpful, and professional.”

Discussion

In the first 4 weeks of the COVID-19 response, a large and diverse academic GI/hepatology practice provided 94% of visits through telemedicine. Early feedback from patients was generally positive, with two-thirds of telemedicine visits rated as good/better than face-to-face. Notable differences in telemedicine acceptability, video vs telephone use, and online portal use as a surrogate measure of digital literacy were noted for Black race and older age. We present data that were influenced by early COVID-19 experiences, which may have been the most challenging time for adoption. Future studies can investigate patient and clinician perceptions after more experience with telemedicine, the optimal integration of face-to-face and telemedicine visits, and potential facilitators and barriers of telemedicine.6 Practices should continue work to mitigate disparities in access to technology and low digital literacy.7

Acknowledgements

Dr Serper's time was supported by grant number K23DK115897, and Dr Mehta’s time was supported by grant number K08CA234326 from the National Institutes of Health.

Alex Burdzy, Patrik Garren, and Christopher Snider contributed to the data acquisition and implementation of the study.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Marina Serper, MD, MS (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Lead; Methodology: Equal; Resources: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead). Frederick Nunes, MD (Conceptualization: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting). Nuzhat Ahmad, MD (Conceptualization: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting). Divya Roberts, CRNP (Data curation: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Supporting). David Metz, MD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting). Shivan Mehta, MD, MBA, MSHP (Conceptualization: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.034

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Patient Perceptions of Telemedicine Visits Stratified by Visit Method, Age, and Portal Use

| Variable | Level | Overall (N = 788) | Telephone (n = 573) | Video (n = 215) | P valuea | Age <60 (n = 388) | Age 60+ (n = 400) | P valuea | No portal use (n = 206) | Portal Use (n = 582) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | < 30 | 63 (8.0) | 42 (7.3) | 21 (9.8) | .033 | ... | ... | 14 (6.8) | 49 (8.4) | .053 | |

| 30-39 | 84 (10.7) | 53 (9.2) | 31 (14.4) | ... | ... | 12 (5.8) | 72 (12.4) | ||||

| 40-49 | 83 (10.5) | 60 (10.5) | 23 (10.7) | ... | ... | 22 (10.7) | 61 (10.5) | ||||

| 50-59 | 158 (20.1) | 109 (19.0) | 49 (22.8) | ... | ... | 40 (19.4) | 118 (20.3) | ||||

| ≥60 | 400 (50.8) | 309 (53.9) | 91 (42.3) | ... | ... | 118 (57.3) | 282 (48.5) | ||||

| Sex | Female | 466 (59.1) | 339 (59.2) | 127 (59.1) | >.99 | 228 (58.8) | 238 (59.5) | .88 | 128 (62.1) | 338 (58.1) | .32 |

| Male | 322 (40.9) | 234 (40.8) | 88 (40.9) | 160 (41.2) | 162 (40.5) | 78 (37.9) | 244 (41.9) | ||||

| Visit method | Telephone | 573 (72.7) | ... | ... | 264 (68.0) | 309 (77.3) | .004 | 180 (87.4) | 393 (67.5) | <.001 | |

| Video | 215 (27.3) | ... | ... | 124 (32.0) | 91 (22.8) | 26 (12.6) | 189 (32.5) | ||||

| How did video visit compare to face-to-face | Worse | 139 (18.2) | 111 (20.1) | 28 (13.4) | .007 | 60 (15.8) | 79 (20.6) | .001 | 60 (29.1) | 79 (14.2) | <.001 |

| As good | 396 (52.0) | 286 (51.7) | 110 (52.6) | 206 (54.4) | 190 (49.6) | 93 (45.1) | 303 (54.5) | ||||

| Better | 112 (14.7) | 68 (12.3) | 44 (21.1) | 69 (18.2) | 43 (11.2) | 30 (14.6) | 82 (14.7) | ||||

| Not sure | 115 (15.1) | 88 (15.9) | 27 (12.9) | 44 (11.6) | 71 (18.5) | 23 (11.2) | 92 (16.5) | ||||

| Any concerns about telemedicine | No | 744 (94.4) | 539 (94.1) | 205 (95.3) | .60 | 370 (95.4) | 374 (93.5) | .28 | 197 (95.6) | 547 (94.0) | .48 |

| Yes | 44 (5.6) | 34 (5.9) | 10 (4.7) | 18 (4.6) | 26 (6.5) | 9 (4.4) | 35 (6.0) | ||||

| Ease of software download/use | Very dissatisfied | 16 (2.1) | 16 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | .012 | 5 (1.3) | 11 (2.8) | .67 | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.9) | .002 |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 15 (2.0) | 11 (2.0) | 4 (1.9) | 8 (2.1) | 7 (1.8) | 3 (1.5) | 12 (2.1) | ||||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 25 (3.3) | 15 (2.7) | 10 (4.8) | 12 (3.2) | 13 (3.4) | 10 (4.9) | 15 (2.7) | ||||

| Somewhat satisfied | 97 (12.7) | 63 (11.3) | 34 (16.3) | 47 (12.4) | 50 (13.0) | 37 (18.0) | 60 (10.7) | ||||

| Very satisfied | 612 (80.0) | 451 (81.1) | 161 (77.0) | 307 (81.0) | 305 (79.0) | 156 (75.7) | 456 (81.6) | ||||

| Overall satisfaction with healthcare quality | Very dissatisfied | 21 (2.7) | 20 (3.6) | 1 (0.5) | .078 | 10 (2.6) | 11 (2.8) | .20 | 3 (1.5) | 18 (3.2) | .040 |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 7 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (1.1) | ||||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 2 (2.9) | 18 (3.2) | 4 (1.9) | 9 (2.4) | 13 (3.4) | 12 (5.8) | 10 (1.8) | ||||

| Somewhat satisfied | 90 (11.8) | 61 (11.0) | 29 (13.9) | 51 (13.5) | 39 (10.1) | 23 (11.2) | 67 (12.0) | ||||

| Very satisfied | 625 (81.7) | 452 (81.3) | 173 (82.8) | 308 (81.3) | 317 (82.1) | 167 (81.1) | 458 (81.9) | ||||

| Overall satisfaction with telemedicine experience | Very dissatisfied | 19 (2.5) | 18 (3.2) | 1 (0.5) | .18 | 7 (1.8) | 12 (3.1) | .68 | 1 (0.5) | 18 (3.2) | .046 |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 9 (1.2) | 6 (1.1) | 3 (1.4) | 6 (1.6) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.0) | 7 (1.3) | ||||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 21 (2.7) | 17 (3.1) | 4 (1.9) | 11 (2.9) | 10 (2.6) | 10 (4.9) | 11 (2.0) | ||||

| Somewhat satisfied | 100 (13.1) | 72 (12.9) | 28 (13.4) | 49 (12.9) | 51 (13.2) | 28 (13.6) | 72 (12.9) | ||||

| Very satisfied | 616 (80.5) | 443 (79.7) | 173 (82.8) | 306 (80.7) | 310 (80.3) | 165 (80.1) | 451 (80.7) | ||||

| Would use telemedicine in the future | Probably will not | 60 (8.0) | 52 (9.6) | 8 (3.9) | .006 | 21 (5.7) | 39 (10.3) | .005 | 31 (15.8) | 29 (5.3) | <.001 |

| Not Sure | 54 (7.2) | 36 (6.6) | 18 (8.8) | 26 (7.0) | 28 (7.4) | 12 (6.1) | 42 (7.6) | ||||

| Probably will | 291 (38.9) | 221 (40.7) | 70 (34.1) | 131 (35.5) | 160 (42.2) | 71 (36.2) | 220 (39.9) | ||||

| Definitely will | 343 (45.9) | 234 (43.1) | 109 (53.2) | 191 (51.8) | 152 (40.1) | 82 (41.8) | 261 (47.3) | ||||

| Net promoter scoreb | 49 | 45 | 54 | .099 | 45 | 54 | .21 | 50 | 45 | .57 |

NOTE: Data are presented as number (%) unless noted otherwise.

Bold P values are statistically significant (P < .05).

A score of ≥50 is considered excellent, and ≥40 is considered good.

Supplementary Table 2.

Clinician Attitudes Toward Telemedicine in the First 4 Weeks of COVID-19 Response Stratified by Years in Practice

| Total (N = 63) | In practice <20 years (n = 47) | In practice ≥20 years (n = 16) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider type | .006 | |||

| Advanced practice provider | 16 (25.4) | 16 (34) | 0 (0) | |

| Physician | 47 (74.6) | 31 (66) | 16(100) | |

| Years in practice | <.001 | |||

| 0-5 | 25 (39.7) | 25 (53) | 0 (0) | |

| 6-10 | 11 (17.5) | 11 (23) | 0 (0) | |

| 11-20 | 11 (17.5) | 11 (23) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥20 | 16 (25.4) | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 33 (52.4) | 31 (66) | 2 (13) | <.001 |

| Male | 30 (47.6) | 16 (34) | 14 (88) | |

| Age, y | <.001 | |||

| 30-39 | 29 (46.0) | 29 (62) | 0 (0) | |

| 40-49 | 14 (22.2) | 14 (30) | 0 (0) | |

| 50-59 | 13 (20.6) | 3 (6) | 10 (63) | |

| ≥60 | 7 (11.1) | 1 (2) | 6 (38) | |

| Telephone telemedicine | >.99 | |||

| No | 1 (1.6) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Yes | 62 (98.4) | 46 (98) | 16 (100) | |

| Video telemedicine | >.99 | |||

| No | 4 (6.3) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Yes | 59 (93.7) | 46 (98) | 16 (100) | |

| How did video visit compare to face-to-face | <.001 | |||

| Better | 6 (10.2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| As good | 36 (61.0) | 46 (98) | 16 (100) | |

| Worse | 16 (27.1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Not sure | 1 (1.7) | 46 (98) | 16 (100) | |

| How did telephone visit compare to in-person | .79 | |||

| Better | 4 (6.5) | 4 (9) | 0 (0) | |

| As good | 21 (33.9) | 16 (35) | 5 (31) | |

| Worse | 33 (53.2) | 23 (50) | 10 (63) | |

| Not sure | 4 (6.5) | 3 (7) | 1 (6) | |

| Any concerns about telemedicine prior to starting | .38 | |||

| No | 28 (44.4) | 19 (40) | 9 (56) | |

| Yes | 35 (55.6) | 28 (60) | 7 (44) | |

| Ease of software download | .076 | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 2 (3.3) | 1 (2) | 1 (6) | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 4 (6.6) | 2 (4) | 2 (13) | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 14 (23.0) | 9 (20) | 5 (31) | |

| Very satisfied | 40 (65.6) | 33 (73) | 7 (44) | |

| Overall satisfaction with conducting telemedicine | >.99 | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 1 (1.6) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 7 (11.3) | 5 (11) | 2 (13) | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 28 (45.2) | 21 (46) | 7 (44) | |

| Very satisfied | 26 (41.9) | 19 (41) | 7 (44) | |

| Overall satisfaction with care provided | .057 | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 1 (1.6) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (19) | |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 6 (9.7) | 4 (9) | 2 (13) | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 25 (40.3) | 20 (43) | 5 (31) | |

| Very satisfied | 27 (43.5) | 21 (46) | 6 (38) | |

| Would use telemedicine in the future | .12 | |||

| Probably will not | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |

| Not Sure | 3 (4.9) | 1 (2) | 2 (13) | |

| Probably will | 13 (21.3) | 10 (22) | 3 (19) | |

| Definitely will | 44 (72.1) | 34 (76) | 10 (63) | |

| Net promoter scoreb | 52 | 54 | 44 | NS |

NOTE: Data are presented as number (%) unless noted otherwise.

Bold P values are statistically significant (P < .05); NS, indicates not significant.

A score of ≥50 is considered excellent, and ≥40 is considered good.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet#:∼:text=Telehealth%2C%20telemedicine%2C%20and%20related%20terms,provision%20°f%20healthcare%20is%20increasing

- 2.National Institutes of Health https://www.nibib.nih.gov/science-education/science-topics/telehealth

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-issues-second-round-sweeping-changes-support-us-healthcare-system-during-covid

- 4.Serper M. Hepatology. 2020;72(2):723–728. doi: 10.1002/hep.31276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polinski J.M. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):269–275. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3489-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehta S.J. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16:1014–1017. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.12.msoc1-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nouri S, et al. NEJM Catalyst May 2020