The intestinal microbiota is critical to host physiology, metabolism, and health. However, the fungal community has been often overlooked. Recent studies in humans have highlighted the importance of the mycobiota in obesity and disease, making it imperative that we increase our understanding of the fungal community. The significance of this study is that we revealed the spatial and temporal changes of the mycobiota in the GI tract of the chicken, a nonmammalian species. To our surprise, the chicken intestinal mycobiota is dominated by a limited number of fungal species, in contrast to the presence of hundreds of bacterial taxa in the bacteriome. Additionally, the chicken intestinal fungal community is more diverse in the upper than the lower GI tract, while the bacterial community shows an opposite pattern. Collectively, this study lays an important foundation for future work on the chicken intestinal mycobiome and its possible manipulation to enhance animal performance and disease resistance.

KEYWORDS: mycobiome, bacitracin methylene disalicylate, chickens, microbiome, microbiota, mycobiota, poultry

ABSTRACT

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract harbors a diverse population of microorganisms. While much work has been focused on the characterization of the bacterial community, very little is known about the fungal community, or mycobiota, in different animal species and chickens in particular. Here, we characterized the biogeography of the mycobiota along the GI tract of day 28 broiler chicks and further examined its possible shift in response to bacitracin methylene disalicylate (BMD), a commonly used in-feed antibiotic, through Illumina sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) region of fungal rRNA genes. Out of 124 samples sequenced, we identified a total of 468 unique fungal features that belong to four phyla and 125 genera in the GI tract. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota represented 90% to 99% of the intestinal mycobiota, with three genera, i.e., Microascus, Trichosporon, and Aspergillus, accounting for over 80% of the total fungal population in most GI segments. Furthermore, these fungal genera were dominated by Scopulariopsis brevicaulis (Scopulariopsis is the anamorph form of Microascus), Trichosporon asahii, and two Aspergillus species. We also revealed that the mycobiota are more diverse in the upper than lower GI tract. The cecal mycobiota transitioned from being S. brevicaulis dominant on day 14 to T. asahii dominant on day 28. Furthermore, 2-week feeding of 55 mg/kg BMD tended to reduce the cecal mycobiota α-diversity. Taken together, we provided a comprehensive biogeographic view and succession pattern of the chicken intestinal mycobiota and its influence by BMD. A better understanding of intestinal mycobiota may lead to the development of novel strategies to improve animal health and productivity.

IMPORTANCE The intestinal microbiota is critical to host physiology, metabolism, and health. However, the fungal community has been often overlooked. Recent studies in humans have highlighted the importance of the mycobiota in obesity and disease, making it imperative that we increase our understanding of the fungal community. The significance of this study is that we revealed the spatial and temporal changes of the mycobiota in the GI tract of the chicken, a nonmammalian species. To our surprise, the chicken intestinal mycobiota is dominated by a limited number of fungal species, in contrast to the presence of hundreds of bacterial taxa in the bacteriome. Additionally, the chicken intestinal fungal community is more diverse in the upper than the lower GI tract, while the bacterial community shows an opposite pattern. Collectively, this study lays an important foundation for future work on the chicken intestinal mycobiome and its possible manipulation to enhance animal performance and disease resistance.

INTRODUCTION

The intestinal tract is home to a diverse microbial population consisting primarily of bacteria with smaller populations of fungi, archaea, protozoa, and viruses (1, 2). To date, extensive work has been performed to characterize the intestinal bacterial community. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota is known to be associated with a variety of intestinal and extraintestinal diseases (1, 2). However, very little is known about nonbacterial populations of the intestinal tract. Recently, increased work has been conducted to understand the fungal community of the human intestinal microbiota, known as the mycobiota, and its role in health and disease (3, 4). While large individual variations have been observed, human oral and intestinal fungi are known to belong primarily to the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, with genera such as Saccharomyces, Candida, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Penicillium, Wallemia, Malassezia, Aureobasidium, and Epicoccum being most often observed (3–5). Although fungal species comprise fewer than 1% of the microorganisms in the human intestinal tract, recent work has demonstrated their ability to modulate the innate and adaptive immune systems (6–8). Fungal dysbiosis has been linked to multiple diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, allergic airway disease, atopic dermatitis, and alcoholic liver disease (3, 4, 9).

To date, most of the mycobiota research has focused on humans and mice. Little is known regarding the intestinal mycobiota of livestock animals and nonruminants in particular. Ruminant mycobiome research has primarily focused on anaerobic fungi belonging to the phylum Neocallimastigomycota (10–14). First discovered in the rumen of sheep (15), anaerobic fungi are thought to be the first to attach to fibrous material (16) and contribute more to the degradation of plant material than cellulolytic bacteria (17). In pigs, Kazachstania slooffiae was the most frequently detected species in weaned Landrace pigs in a culture-based study (18), whereas deep sequencing identified Kazachstania telluris as the dominant fungal species in a miniature breed of weaned pigs (19).

In limited poultry mycobiome studies, all but one were culture based, and most were restricted only to the cecum (20–25). Candida or Aspergillus was revealed to be predominant in the chicken cecum in culture-dependent studies. Surprisingly, the study that employed a culture-independent pyrosequencing approach only detected two Cladosporium species in the cecum of broilers fed an unmedicated diet, although another 17 fungal species were detected in animals supplemented with essential oils (20). Therefore, we sought to comprehensively characterize the biogeography of the intestinal mycobiome of broiler chickens by using Illumina deep sequencing of the luminal contents throughout the GI tract.

The intestinal bacterial community undergoes age-dependent changes and eventually becomes stabilized as animals mature (13, 26–28). However, very limited studies were conducted to reveal whether the intestinal fungal community shifts with age. Additionally, antibiotics are well-known to modulate chicken intestinal bacteriome (29–32). It will be important to know whether in-feed antibiotics could potentially alter the intestinal mycobiome. Therefore, we investigated the succession and the effect of subtherapeutic and therapeutic supplementation of bacitracin methylene disalicylate (BMD), a commonly used in-feed antibiotic, on the chicken cecal mycobiome composition in this study.

RESULTS

Biogeography of the chicken intestinal mycobiota.

To characterize the biogeography of chicken intestinal mycobiota, Illumina sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) region was performed with the luminal microbial DNA isolated from eight different segments of the GI tract (crop, ventriculus, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon, and cloaca) of 12 day 28 male Cobb broilers. Following quality control, 30,794,134 high-quality sequencing reads were obtained with an average of 246,353 sequences per sample. Sequences were further denoised using Deblur, and reads present in less than 5% samples were removed, resulting in the identification of a total of 468 features at single-nucleotide resolution.

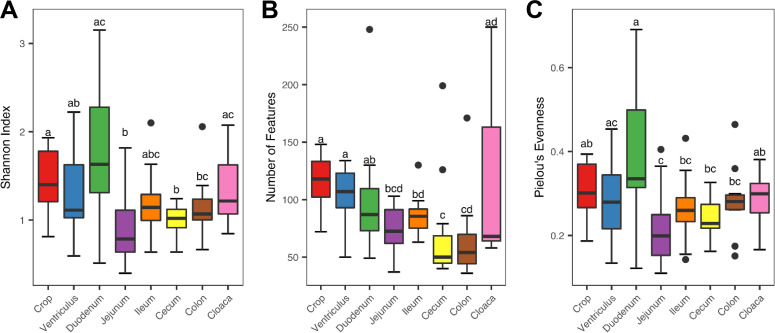

The α-diversity of the intestinal mycobiota was determined using the Shannon index (Fig. 1A), number of observed features (Fig. 1B), and Pielou’s evenness index (Fig. 1C). A significant difference (P < 0.05) in the α-diversity was revealed across the GI tract in all three indices. Overall, the mycobiome in the upper GI tract (the crop, ventriculus, and duodenum) tended to be more diverse than those in the lower GI tract (the jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon) in the Shannon index and richness. In contrast to the microbiome, the mycobiome in the cecum and colon consisted of the lower number of fungi (Fig. 1B), with a minimum overall diversity relative to other GI locations (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the overall mycobiome diversity appeared to be highest in the duodenum and lowest in the jejunum (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

Variation in the α-diversity of the mycobiome along the gastrointestinal tract of day 28 chickens. Newly hatched chicks were fed an unmedicated basal diet for 28 days before the luminal content samples were collected from each gastrointestinal segment. The diversity and richness were calculated from 12 samples of each segment and indicated by the Shannon index (A), number of features (B), and Pielou’s evenness index (C). The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed, and the means were separated with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with the segments not sharing a common superscript being considered significantly different (P < 0.05).

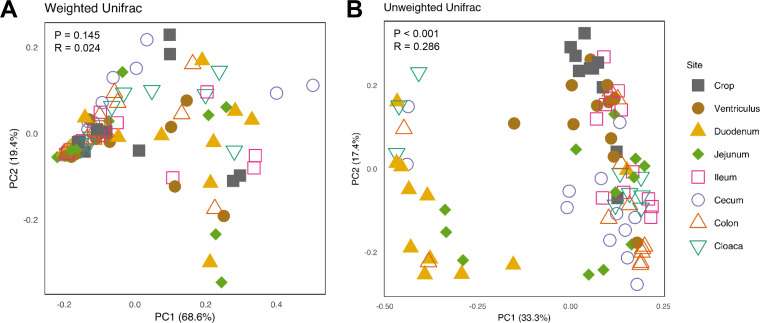

To measure the difference in the mycobiota composition among the GI locations, β-diversity analysis was performed using the weighted and unweighted UniFrac indices. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) revealed no tendency for the data to form obvious clusters for the weighted UniFrac distance matrix (i.e., there was no significant difference [P = 0.145]) based on analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) (Fig. 2A). However, a significant difference (P = 0.001) was observed for the unweighted UniFrac index, with an R value of 0.286 (Fig. 2B). For example, the duodenum and crop formed rather distinct clusters from others (Fig. 2B). Pairwise comparisons of the unweighted UniFrac index indeed revealed clear significant differences in most comparisons (P < 0.05), with a few R values approaching 0.8 (Table S1 in the supplemental material). Overall, these results indicated a distinct biogeographic pattern of the mycobiota throughout the GI tract of broiler chickens.

FIG 2.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the mycobiome along the gastrointestinal tract of day 28 chickens. Newly hatched chicks were fed an unmedicated basal diet for 28 days before the luminal content samples were collected from each gastrointestinal segment. Each data point represents an individual sample. PCoA was calculated from 12 samples of each segment using weighted (A) and unweighted (B) UniFrac indices. Statistical significance was determined using ANOSIM and indicated in each plot.

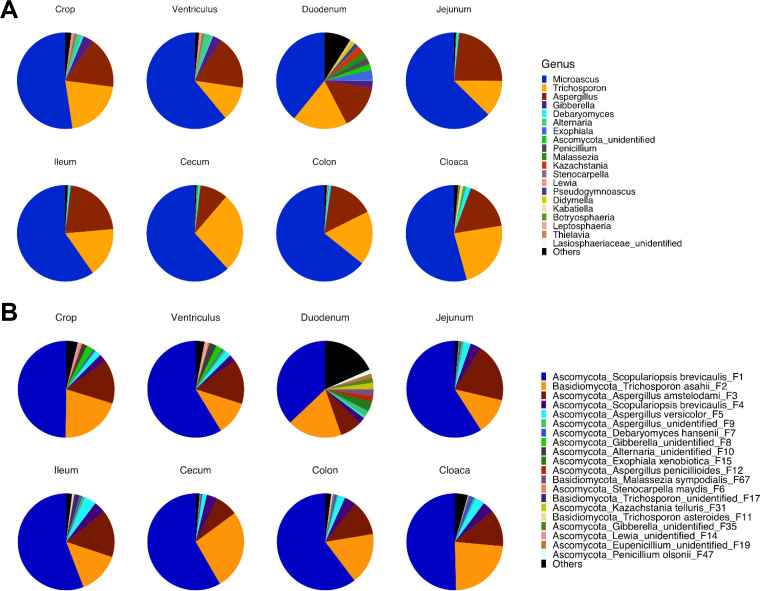

To further reveal the mycobiota composition in different GI segments of broiler chickens, relative abundance was calculated at both the phylum, genus, and feature levels. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were the two most dominant phyla throughout the GI tract, representing 89% to 99.9% of the total fungal population in any given segment (data not shown). While Ascomycota accounted for 73.2% to 88.3% of the fungi, Basidiomycota amounted to 11.7% to 26.8% (data not shown). At the genus level, Microascus and Aspergillus were the two most dominant genera of Ascomycota, with the former representing 39.2% to 64.2% and the latter varying between 9.4% and 23.3% of the total fungal population in different GI segments (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, Basidiomycota was primarily dominated by Trichosporon, which accounted for greater than 99% of Basidiomycota (Fig. 3A). Zygomycota and Glomeromycota were two minor phyla detected at an average of less than 0.1% in each GI location, and approximately 0.02% of fungi failed to be classified.

FIG 3.

The mycobiota composition in different segments of the gastrointestinal tract of day 28 chickens. Newly hatched chicks were fed an unmedicated basal diet for 28 days before the luminal content samples were collected from each gastrointestinal segment. The relative abundance of features was used to determine the fungal composition at the genus (A) and feature (B) levels with 12 samples of each segment. Only the top 20 genera and features are shown, with unidentified and low-abundance fungi being collectively denoted as “Others.”

It is evident that the intestinal mycobiota appeared to be rather limited in diversity, with the top 20 features accounting for 81.7% to 98.7% of the total fungal population in any given intestinal segment (Fig. 3B and Table S2). In fact, the top five features accounted for 89.4% to 96.9% of the total fungal population in all GI locations except for the duodenum, where only 65.4% of the reads were represented by these five features. A BLAST search of the GenBank nucleotide database confirmed that both features F1 and F4 are 100% identical to Scopulariopsis brevicaulis (Scopulariopsis is the anamorph form of Microascus) in the sequenced ITS2 region, while F2 was 100% identical to Trichosporon asahii (data not shown). F3 was 100% identical to Aspergillus amstelodami, Aspergillus cristatus, and Aspergillus chevalieri, whereas F5 was identical to Aspergillus versicolor and Aspergillus sydowii. It is noted that two Microascus features (F1 and F4) only differed by two nucleotides (data not shown), suggesting that they are two closely related strains of S. brevicaulis.

Compositionally, the top four features were constantly present with no significant differences among different GI segments, while a majority of the remaining top 20 features showed significant differential enrichment (false-discovery rate [FDR] < 0.05) (Table S2). For example, Aspergillus F5 was the most abundant in the ileum (3.95%) but with the lowest abundance in the duodenum (0.58%) (Table S2). Interestingly, the remaining features that were significantly differentially enriched showed one of two different expression patterns. While the relative abundance of four features (F6, F8, F10, and F14) was the highest in the crop and ventriculus with an extremely low presence in the remaining GI locations, the other six features (F12, F15, F19, F35, F47, and F67) were marked by preferential enrichment in the duodenum with virtually no presence in any other intestinal segments (Table S2).

Succession of the cecal mycobiota.

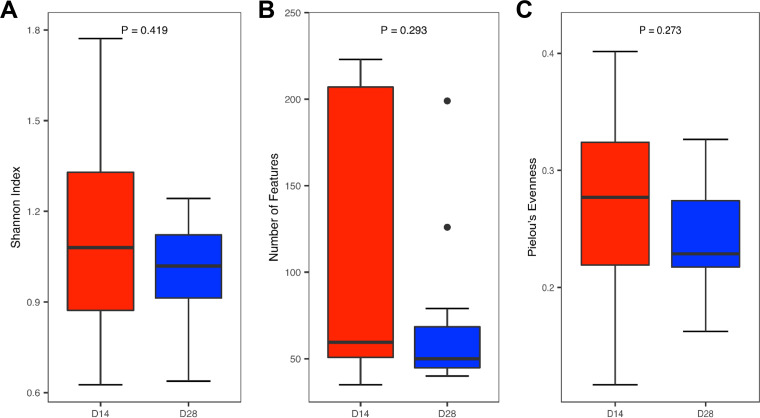

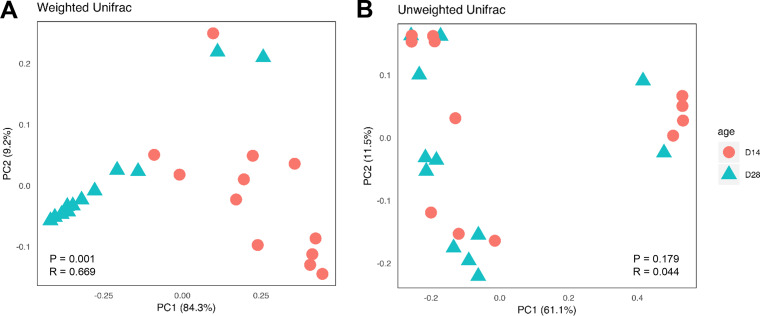

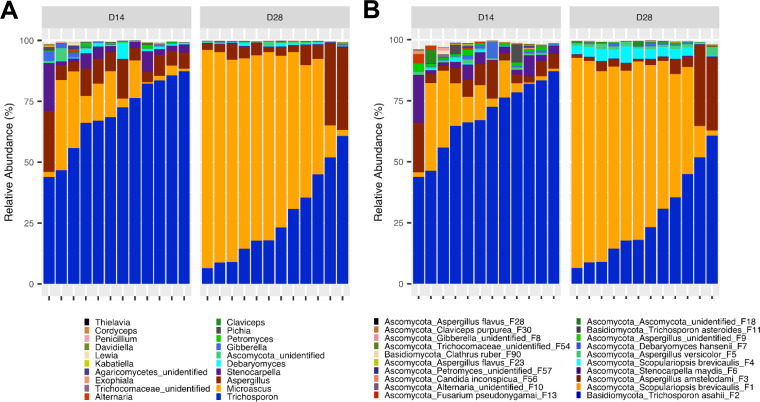

To evaluate developmental changes of the intestinal mycobiota, the cecal contents were collected from 12 healthy male Cobb broiler chickens at 14 and 28 days of age and analyzed for their mycobiota compositions. No significant difference was observed in any of the three α-diversity indices measured (Shannon index, number of features, and Pielou’s evenness) (Fig. 4). However, a larger interindividual variation appeared to be present on day 14 than on day 28. This was especially true for sample richness. Additionally, β-diversity analysis revealed a significant separation between day 14 and day 28 for the weighted (P = 0.001) (Fig. 5A) but not unweighted UniFrac index (P = 0.179) (Fig. 5B). R values of 0.669 for the weighted UniFrac index indicated the separation to be rather substantial.

FIG 4.

Changes in the α-diversity of the cecal mycobiome between day 14 and day 28 chickens. Newly hatched chicks were fed an unmedicated basal diet before the cecal content samples were collected on days 14 and 28. The diversity and richness were calculated from 12 samples on each sampling day and indicated by the Shannon index (A), number of features (B), and Pielou’s evenness index (C). Significant differences were determined using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

FIG 5.

PCoA of the cecal mycobiome in day 14 and day 28 chickens. Newly hatched chicks were fed an unmedicated basal diet before the cecal content samples were collected on days 14 and 28. Each data point represents an individual sample. PCoA was calculated from 12 samples on each sampling day using weighted (A) and unweighted (B) UniFrac indices. Statistical significance was determined using ANOSIM and indicated in each plot.

Compositionally, the cecal mycobiome did appear to undergo a substantial shift. While Trichosporon was the most predominant fungus in the cecum of day 14 broilers, it was replaced by Microascus by day 28 (Fig. 6A). In fact, the day 14 cecal mycobiota was dominated by T. asahii (F2), followed by members of S. brevicaulis (F1 and F4), Aspergillus (F3), and Stenocarpella maydis (F6) (Fig. 6B). On day 28, two S. brevicaulis features (F2 and F4) were drastically increased at the expense of T. asahii. Statistical analysis of the top 20 features using the Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a significant decrease (FDR ≤ 0.05) in T. asahii (F2) and S. maydis features (F6) (Table S3). This was associated with a significant increase (FDR = 0.021) in the S. brevicaulis features (F1 and F4). None of the remaining top 20 features were significantly affected by age (FDR > 0.05) (Table S3).

FIG 6.

The mycobiota composition in the cecum of day 14 and day 28 chickens. Newly hatched chicks were fed an unmedicated basal diet before the cecal content samples were collected on days 14 and 28. Relative abundance of individual features was used to determine the fungal composition at the genus (A) and feature (B) levels with 12 samples on each sampling day. Only the top 20 genera and features are shown.

Effect of BMD on the cecal mycobiome.

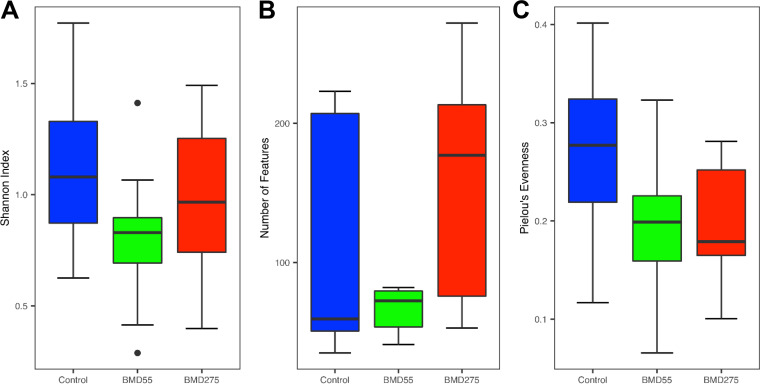

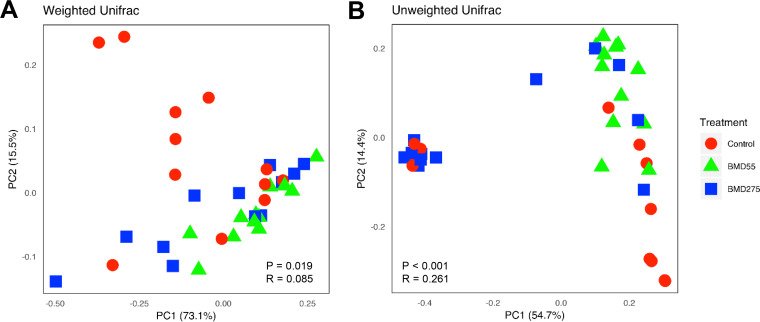

To determine the potential effect of antibiotics on intestinal mycobiota, day-of-hatch male Cobb chicks were fed unmedicated feed or feed supplemented with either a subtherapeutic (55 mg/kg) or therapeutic (275 mg/kg) level of BMD, a commonly used in-feed antibiotic, continuously for 14 days, followed by analysis of the cecal contents from 12 chickens in each of the three groups. Although we failed to observe any significant difference in growth performance of chickens (data not shown), the α-diversity analysis of the cecal mycobiome revealed a strong tendency for a decrease (P = 0.06) in the overall diversity in response to subtherapeutic BMD (Fig. 7A). However, the shift was subtler for the therapeutic group. The cecal mycobiota richness appeared to dose-dependently increase in response to BMD, with the therapeutic group being noticeably greater than both the control and subtherapeutic BMD (P = 0.08). (Fig. 7B). Conversely, evenness appeared to dose-dependently decrease in response to BMD (P = 0.08) (Fig. 7C). It is noted that subtherapeutic BMD also appeared to reduce individual variations in both the diversity and richness of the cecal mycobiota. β-Diversity analysis did reveal a significant difference in the mycobiome composition as measured by both weighted UniFrac (P = 0.019) (Fig. 8A) and unweighted UniFrac (P < 0.001) (Fig. 8B). Pairwise ANOSIM using the weighted UniFrac index revealed subtherapeutic BMD composition to be significantly different from the control (P = 0.005; R = 0.186) but not therapeutic BMD (P = 0.158) (Table S4). Therapeutic BMD was not significantly different from the control either (P = 0.190). For the unweighted UniFrac, the mycobiome composition in the subtherapeutic BMD group was significantly different from both the control (P = 0.001; R = 0.346) and the therapeutic BMD group (P < 0.001; R = 0.426) (Table S4).

FIG 7.

Effect of BMD on the α-diversity of the chicken cecal mycobiota. The cecal content samples were collected 14 days after day-of-hatch chickens were fed an unmedicated diet or the diet supplemented with 55 or 275 mg/kg of BMD. The diversity and richness were calculated from 12 samples in each treatment and indicated by the Shannon index (A), number of features (B), and Pielou’s evenness index (C). Means were separated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and they are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

FIG 8.

Effect of BMD on the β-diversity of the chicken cecal mycobiota. The cecal content samples were collected 14 days after day-of-hatch chickens were fed an antibiotic-free diet or the diet supplemented with 55 or 275 mg/kg of BMD. PCoA was performed with 12 samples in each treatment using weighted (A) and unweighted (B) UniFrac indices. Each data point represents an individual sample. Statistical significance was determined using ANOSIM and indicated in each plot.

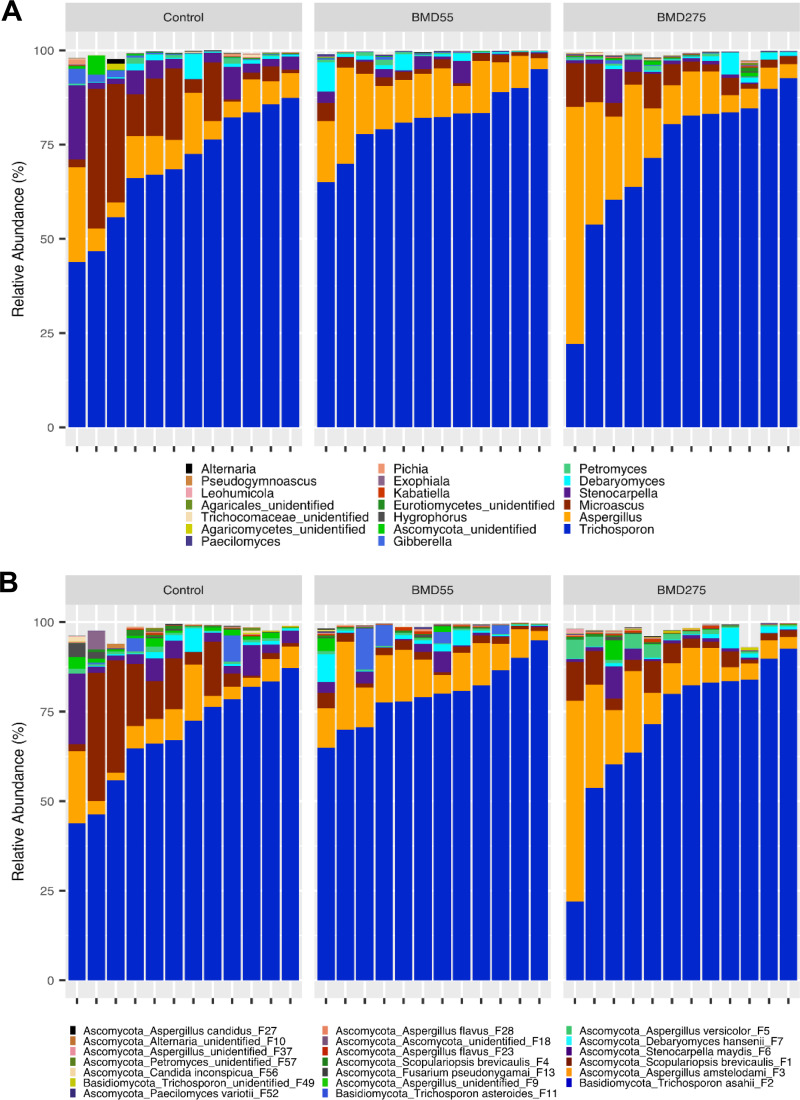

Investigation of the mycobiota composition in the chicken cecum revealed no significant difference (FDR > 0.05) in any of the top 20 fungal features in response to subtherapeutic or therapeutic BMD (Fig. 9; Table S5). However, numerical shifts in the top four features were observed, including an increase in A. amstelodami (F3) and a decrease in S. brevicaulis (F1) and S. maydis (F6) in both BMD groups. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to further elucidate the relationship between relative abundance of individual features and BMD inclusion level. However, none of the features showed a significant correlation (FDR ≤ 0.05) with the BMD levels.

FIG 9.

Effect of BMD on the chicken cecal mycobiota composition. The cecal content samples were collected 14 days after day-of-hatch chickens were fed an unmedicated diet or the diet supplemented with 55 or 275 mg/kg of BMD. The relative abundance of each feature was to determine the fungal composition at the genus (A) and feature (B) levels, with 12 samples on each sampling day. Only the top 20 genera and features are shown.

DISCUSSION

While extensive work has been performed in multiple animal species to characterize the intestinal bacterial population and its relationship with health and disease, very little is known about the intestinal mycobiota, particularly in chickens. The fungal community is estimated to account for approximately 0.02% of the intestinal mucosa-associated microbiota and 0.03% of the fecal microbiota in humans, albeit with large variations among individuals (29). In humans and mice, members of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota predominate, with a low abundance of Zygomycota and Chytridiomycota in the GI tract (3, 30). Culture-dependent studies have long identified members of the genus Candida to be prevalent in the human GI tract (3), while culture-independent techniques have typically revealed the presence of less than 100 fungal genera, with Candida, Penicillium, Wallemia, Cladosporium, Cladosporium, and Saccharomyces being the most prevalent in the stools of healthy individuals (3, 4). To date, at least 50 different fungal genera have been identified in mice, with Candida, Saccharomyces, and Cladosporium being the most common (4). Next-generation sequencing of swine intestinal mycobiota has revealed the presence of three phyla (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Zygomycota) and 67 genera (19). The phylum Ascomycota accounts for more than 97% of the sequence reads, while Kazachstania, a genus of Ascomycota, is represented by over 78% of the sequences (19).

Previous limited investigations into the poultry mycobiome have relied primarily on culture-based techniques. Using culture methods, most studies have reported fewer than 20 fungal species, and Candida has been frequently described as the most abundant genus in the GI tract of chickens and turkeys, although the dominant Candida species varies among studies (21–24). Besides Candida, Trichosporon, Geotrichum, Rhodotorula, and Saccharomyces have been reported in chickens as well (21–23). However, one other culture-dependent study reported the identification of 88 fungal species from over 3,000 cecal samples of broiler and layer chickens, with Aspergillus, Penicillium, Verticillium, and Sporidiobolus being the top four genera (25), whereas a culture-independent 454 pyrosequencing method only revealed two fungal species, Cladosporium sp. and Cladosporium sphaerospermum, in the cecum of broilers fed unmedicated diets (20), presumably due to a lack of sequencing depth.

In this study, among the fungal taxa that are present in at least 5% of 124 samples, we identified a total of 468 unique fungal features that belong to 4 phyla and 125 genera in the chicken GI tract. Consistent with previous studies in chickens and other animal species (3, 4, 19–25, 30), our Illumina deep sequencing revealed a high abundance of Ascomycota throughout the GI tract of broiler chickens, followed by Basidiomycota in day 28 broiler chickens. Both phyla accounted for greater than 89% of all fungal populations in any segment of the GI tract. Among all classifiable fungi, Microascus, Trichosporon, Aspergillus, and Gibberella were the top four most abundant genera. Clearly, because of the depth of our sequencing approach, we have significantly expanded the repertoire of the fungal community in the GI tract of chickens in this study.

Using the Deblur method of denoising in QIIME 2, we were able to achieve a single-nucleotide resolution in differentiating fungal features. Surprisingly, we identified Microascus as the most dominant intestinal fungal genus in day 28 chickens, with two of the top five features belonging to S. brevicaulis. This is in sharp contrast to previous studies (20–25). Furthermore, we observed that Candida only accounts for less than 0.001% of the total fungal population in the GI tract of both day 14 and day 28 chickens, while others found it to be a major genus. Such apparent discrepancies between ours and several previously published studies (20–25) are likely due to the dietary, environmental, and technical differences among different studies. Most poultry studies relied on culture-based methods (21–25), which are known to be biased toward fast-growing and nonfastidious species (3), so it is not surprising that the Candida species are frequently observed. Additionally, it is well-known that the microorganisms, including fungi present in the diet and on the flooring and caging materials, are among major contributors to the intestinal microbiota (31, 32). Furthermore, the age and genetic background of animals used in several studies could be different. Nevertheless, the remaining top features belong to the genera Trichosporon and Aspergillus, both of which have been reported in humans as well as in chickens (21–23).

It is noted that the top features in our study are most commonly associated with soil or cereal grains, so their presence in the GI tract of broiler chickens likely originated from the diet and the surrounding environment such as wood shavings and the floor. For example, the most dominant Microascus member, S. brevicaulis, in our study is a saprophyte and commonly found in soil, plant litter, wood, dung, and animal remains (33). Other dominant Trichosporon and Aspergillus species are also ubiquitous in soil and commonly associated with decaying plants and food material (34–36), while Gibberella is most likely derived from the corn used in the feed, as it often causes Gibberella ear rot, a fungal disease manifested by the red or pink color of the mold starting at the ear tip of corns (37).

Although they are likely to originate from the diet or the environment, most of these fungi appear to be able to survive in the GI tract because the composition of the four most abundant features remains relatively stable throughout the GI tract. In fact, S. brevicaulis has genetic potential to degrade a large variety of plant substrates (38), while T. asahii can assimilate a large variety of carbon and nitrogen sources (34), which may contribute to their ability to survive and thrive in the poultry GI tract. Whether these dominant fungal species play a beneficial role to the host and how they interact with the host remains unknown. Further work is warranted to better understand the role of these intestinal fungi in nutrient digestion, gut health, and disease resistance of poultry. It is worth noting that many of the Microascus, Trichosporon, and Aspergillus species are considered opportunistic pathogens, particularly in immunocompromised humans (34, 35, 39, 40). For example, S. brevicaulis has been isolated from a number of clinical sites, including superficial and deep tissues as well as the upper and lower respiratory tract of human patients (39, 40). Therefore, these dominant intestinal fungi need to be monitored for possible contamination in poultry meat, litter, aerosol, and processing plants in order to ensure food safety and the safety of personnel.

Similar to the biography of animal intestinal bacteriome, different segments of the GI tract harbored a rather distinct fungal community in chickens. However, to our surprise, the upper GI tract (crop, ventriculus, and duodenum) hosted a more diverse mycobiota than the jejunum, ileum, and cecum. Specifically, the chicken duodenum exhibited the highest diversity, while the cecum showed the least diversity in the fungal community. These observations are opposite from the intestinal bacteriome, which is the most abundant and diverse in the lower GI segments of chickens (41). However, our mycobiome results are consistent with a recent culture-based study showing that the fungal population is the lowest in the cecum of broiler chickens, relative to the jejunum and proventriculus, while layers have the highest fungal load in the cecum (21). In turkeys, 50% of all fungal taxa were cultured from the crop, with 31% coming from the beak cavity and 19% from the cloaca (23). The biogeography of the intestinal mycobiota in humans remains elusive, but a direct comparison of the fungal rRNA copy number among the ileum, cecum, and colon of mice showed a gradual increase in the fungal population along the GI tract (6). UniFrac analysis revealed a significant difference in the mycobiome composition between some, but not all, GI locations. Of note, the duodenum composition was obviously different from all other intestinal segments, while the crop was different from every location except ventriculus. This is in agreement with the increased overall diversity in the upper GI tract. Apparently, additional larger-scale studies on the spatial distribution and absolute quantification of the fungal community in the GI tracts of different animal species are warranted to derive a more definitive conclusion, given large variations in the mycobiota among individuals (42) and the paramount role of the diet and environment in shaping the intestinal microbial community (32).

The intestinal bacterial community typically undergoes age-dependent succession and becomes more diversified and stabilized as animals mature (13, 26–28). While a difference in fungal composition was observed between day 14 and day 28 as measured by the UniFrac indices, no significant difference was seen in α-diversity of the cecal mycobiota. This is most likely due to the large variation observed on day 14. A significant difference in fungal composition was observed as birds aged. In particular, day 28 was marked by an increase in Ascomycota, driven by two S. brevicaulis features (F1 and F4) and a concomitant decrease in Basidiomycota, primarily T. asahii (F2).

Human fecal mycobiota compositions are obviously different among healthy individuals of different age groups (43). Specifically, an inverse relationship between the intestinal fungal α-diversity and age was observed in an earlier human study showing that infants and children harbor more fungal species than adults (43). This is consistent with the numerical, though not statistically significant, decrease in the number of features observed on day 28 relative to day 14. Obviously, sampling beyond 28 days of age is needed to determine whether the chicken intestinal mycobiota could eventually become stabilized and reach “maturity.” Additionally, absolute quantification of the fungal population throughout the GI tract of chickens of different ages is also warranted to assess temporal changes of the overall fungal abundance.

Antibiotics are known to significantly alter gut microbiota of chickens (44–47) and other animal species, including humans (48); however, their impact on the fungal community has not been extensively explored. BMD is a common in-feed antibiotic and a derivative of bacitracin that is mainly active against Gram-positive bacteria by interfering with the synthesis of peptidoglycan, a major bacterial cell wall component (49). In this study, BMD tended to decrease in Shannon index and evenness but increase richness of the chicken cecal mycobiota. Interestingly, UniFrac analysis revealed subtherapeutic BMD to have the strongest effect on the cecal fungal community composition, as therapeutic BMD was not significantly different from control in either the weighted or unweighted UniFrac index. However, no features were shown to be significantly altered by BMD inclusion. A study with human patients who received one of five broad-spectrum antibiotics (ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, imipenem-cilastatin, and aztreonam) for 8 to 10 days found an increase in the population of the fecal mycobiome relative to the pretreatment stage (49). Furthermore, an inverse correlation was observed between the fungal abundance and the anti-anaerobic bacterial activity of the antibiotics (50, 51). A 76-day oral treatment of mice with a mixture of broad-spectrum antibiotics (vancomycin, ampicillin, neomycin, and metronidazole) was found to increase the abundance of the fecal mycobiota by 40-fold, which was declined back to their original abundance after cessation of treatment (50, 51). A decrease in fungal richness was seen in a human patient treated prophylactically with antibiotics (52). Additional studies on the temporal and spatial impact of antibiotics on the absolute and relative abundance of the intestinal mycobiota are warranted.

In summary, we comprehensively investigated the biogeography of the chicken intestinal mycobiota by deep sequencing and revealed by surprise that the upper GI tract harbors a more diverse fungal community than the lower GI tract. Furthermore, the chicken intestinal mycobiota is dominated only by a few major fungal species, showing a much reduced complexity and greater individual variations than the bacteriome. Similar to the intestinal bacteriome, the intestinal mycobiome undergoes a compositional shift as chickens age. Additionally, in-feed antibiotics are capable of altering the fungal community structure, although it is currently unknown whether it is a direct or indirect effect. A better understanding of the intestinal mycobiome provides a foundation for future work into the relationship between the mycobiome and gut health and physiology in poultry, making it possible to modulate intestinal mycobiota to improve animal performance and prevent disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal trials.

All animal trials were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Oklahoma State University under protocol number AG-173. Day-of-hatch male Cobb broiler chicks were obtained from Cobb-Vantress Hatchery (Siloam Springs, AR) and randomly assigned to one of three dietary treatments with 12 birds per cage and 6 cages per treatment. Birds were provided ad libitum access to starter feed and tap water for the entire duration of the trial. Dietary treatments included antibiotic-free standard corn-soybean starter mash diet or the starter mash diet supplemented with BMD at subtherapeutic (55 mg/kg) or therapeutic (275 mg/kg) levels for up to 28 days. Birds were raised on floor cages with fresh dry pine wood shavings under standard management in an environmentally controlled room with temperatures starting at 33°C and decreasing 3°C every 7 days. Lighting for this trial included the light-to-dark ratio of 23:1 from days 0 to 7, 16:8 from days 8 to 22, 17:7 on day 23, and 18:6 from days 24 to 28. To minimize cross-contamination, birds in different treatments were housed in separate rows with physical barriers in between. On days 14 and 28, 2 birds per cage and 12 birds per treatment were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation, and the cecal contents were collected to evaluate the effect of BMD on the cecal mycobiome. Additionally, the luminal contents were collected from different segments of the GI tract (crop, ventriculus, midduodenum, midjejunum, midileum, cecum, colon, and cloaca) on day 28 from 12 control birds for characterization of the chicken intestinal mycobiome. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until further processing.

DNA isolation and sequencing.

Microbial DNA was isolated from intestinal contents using the ZR Fecal 96-well DNA isolation kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA quality and quantity were determined using Nanodrop ND-1000, and the absence of degradation was confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis. High-quality DNA was shipped on dry ice to Novogene (Beijing, CA) for next-generation PE250 sequencing of the ITS2 gene using the ITS3 (GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC) and ITS4 (TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) primers on an Illumina HiSeq platform. PCR amplification and library preparation were performed by Novogene using the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA).

Bioinformatic analysis and statistics.

Illumina paired-end reads were analyzed using the deblur program (53) in QIIME 2 (version 2019.7) (54). Deblur is capable of achieving single-nucleotide resolution based on error profiles within samples, and it produces denoised sequences, known as amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or exact sequence variants (ESVs), which can be compared between studies (53). Fungal sequences were processed using the “deblur denoise-other” option with positive alignment-based filtering against the UNITE reference database. Denoised sequences were classified into fungal features using the Warcup v2 fungal ITS database and the Ribosomal Database Projects (RDP) Bayesian classifier (55, 56). A bootstrap confidence of 80% was used for taxonomic classification. Features with a classification of less than 80% were assigned the name of the last confidently assigned level followed by “_unidentified.” Species classification of the top 20 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) was confirmed through a BLASTN search of the nucleotide database of GenBank. Features appearing in less than 5% of samples were removed from downstream analysis. Data were normalized using cumulative sum scaling in the metagenomeSeq package of R (57). Analysis and visualization of the mycobiota composition were conducted in R version 3.5.1 (58). The α- and β-diversities were calculated with the phyloseq package version 1.24.2 (59). Plots were made using ggplot2 version 3.0.0 (60).

Normality of the data was determined using the Shapiro-Wilks test in R. Significant differences in the α-diversity and the relative abundance were determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test, and multiple comparisons were performed using pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The α-diversity was calculated using the Shannon index, number of features, and Pielou’s evenness indices. Results were plotted using box-and-whisker plots, in which the middle line denotes the median value and the lower and upper hinges represent the first and third quartiles, respectively. Whiskers extend from the hinge to the highest or lowest value, no farther than 1.5× the interquartile range. Points outside this range are considered outliers. The β-diversity was calculated using the weighted and unweighted UniFrac indices as dissimilarity measures of diversity and richness, respectively. Significant differences were determined using ANOSIM in QIIME 2 (61). Spearman correlation analysis was performed to identify a possible correlation between individual features and two levels of BMD inclusion using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Features were considered significant if the FDR was ≤ 0.05.

Accession number.

The raw sequencing reads of this study have been deposited in NCBI under the BioProject accession number PRJNA512838.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jiangchao Zhao at the University of Arkansas for his encouragement in using the Deblur program in QIIME 2. We also appreciate Elizabeth Miller at the University of Minnesota for her guidance on the cumulative sum scaling (CSS) normalization.

This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (grant no. 2018-68003-27462), the Ralph F. and Leila W. Boulware Endowment Fund, and the Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station Project H-3025. K.R. was supported by a USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) predoctoral fellowship grant (2018-67011-28041), while S.B. was supported by the Wentz undergraduate research scholarship at Oklahoma State University.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cani PD. 2018. Human gut microbiome: hopes, threats and promises. Gut 67:1716–1725. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durack J, Lynch SV. 2019. The gut microbiome: relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy. J Exp Med 216:20–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huseyin CE, O'Toole PW, Cotter PD, Scanlan PD. 2017. Forgotten fungi-the gut mycobiome in human health and disease. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:479–511. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuw047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limon JJ, Skalski JH, Underhill DM. 2017. Commensal fungi in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 22:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nash AK, Auchtung TA, Wong MC, Smith DP, Gesell JR, Ross MC, Stewart CJ, Metcalf GA, Muzny DM, Gibbs RA, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF. 2017. The gut mycobiome of the Human Microbiome Project healthy cohort. Microbiome 5:153. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0373-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iliev ID, Funari VA, Taylor KD, Nguyen Q, Reyes CN, Strom SP, Brown J, Becker CA, Fleshner PR, Dubinsky M, Rotter JI, Wang HLL, McGovern DPB, Brown GD, Underhill DM. 2012. Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor dectin-1 influence colitis. Science 336:1314–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.1221789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzetto L, De Filippo C, Cavalieri D. 2014. Richness and diversity of mammalian fungal communities shape innate and adaptive immunity in health and disease. Eur J Immunol 44:3166–3181. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Underhill DM, Iliev ID. 2014. The mycobiota: interactions between commensal fungi and the host immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 14:405–416. doi: 10.1038/nri3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iliev ID, Leonardi I. 2017. Fungal dysbiosis: immunity and interactions at mucosal barriers. Nat Rev Immunol 17:635–646. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonty G, Gouet P, Jouany JP, Senaud J. 1987. Establishment of the microflora and anaerobic fungi in the rumen of lambs. J Gen Microbiol 133:1835–1843. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-7-1835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boots B, Lillis L, Clipson N, Petrie K, Kenny D, Boland T, Doyle E. 2013. Responses of anaerobic rumen fungal diversity (phylum Neocallimastigomycota) to changes in bovine diet. J Appl Microbiol 114:626–635. doi: 10.1111/jam.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kittelmann S, Seedorf H, Walters WA, Clemente JC, Knight R, Gordon JI, Janssen PH. 2013. Simultaneous amplicon sequencing to explore co-occurrence patterns of bacterial, archaeal and eukaryotic microorganisms in rumen microbial communities. PLoS One 8:e47879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dill-McFarland KA, Breaker JD, Suen G. 2017. Microbial succession in the gastrointestinal tract of dairy cows from 2 weeks to first lactation. Sci Rep 7:40864. doi: 10.1038/srep40864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liggenstoffer AS, Youssef NH, Couger MB, Elshahed MS. 2010. Phylogenetic diversity and community structure of anaerobic gut fungi (phylum Neocallimastigomycota) in ruminant and non-ruminant herbivores. ISME J 4:1225–1235. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orpin CG. 1975. Studies on the rumen flagellate Neocallimastix frontalis. J Gen Microbiol 91:249–262. doi: 10.1099/00221287-91-2-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akin DE, Borneman WS. 1990. Role of rumen fungi in fiber degradation. J Dairy Sci 73:3023–3032. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(90)78989-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joblin KN, Campbell GP, Richardson AJ, Stewart CS. 1989. Fermentation of barley straw by anaerobic rumen bacteria and fungi in axenic culture and in co-culture with methanogens. Lett Appl Microbiol 9:195–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1989.tb00323.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urubschurov V, Janczyk P, Souffrant WB, Freyer G, Zeyner A. 2011. Establishment of intestinal microbiota with focus on yeasts of unweaned and weaned piglets kept under different farm conditions. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 77:493–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, Nie Y, Chen J, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Fan Q, Yan X. 2016. Gradual changes of gut microbiota in weaned miniature piglets. Front Microbiol 7:1727. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hume ME, Hernandez CA, Barbosa NA, Sakomura NK, Dowd SE, Oviedo-Rondón EO. 2012. Molecular identification and characterization of ileal and cecal fungus communities in broilers given probiotics, specific essential oil blends, and under mixed Eimeria infection. Foodborne Pathog Dis 9:853–860. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shokri H, Khosravi A, Nikaein D. 2011. A comparative study of digestive tract mycoflora of broilers with layers. Iran J Vet Med 5:1–4. doi: 10.22059/IJVM.2011.22662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanya SH, Sharan NK, Baral BP, Hamal D, Nayak N, Prakash PY, Sathian B, Bairy I, Gokhale S. 2017. Diversity, in-vitro virulence traits and antifungal susceptibility pattern of gastrointestinal yeast flora of healthy poultry, Gallus gallus domesticus. BMC Microbiol 17:113. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sokół I, Gaweł A, Bobrek K. 2018. The prevalence of yeast and characteristics of the isolates from the digestive tract of clinically healthy turkeys. Avian Dis 62:286–290. doi: 10.1637/11780-121117-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cafarchia C, Iatta R, Danesi P, Camarda A, Capelli G, Otranto D. 2019. Yeasts isolated from cloacal swabs, feces, and eggs of laying hens. Med Mycol 57:340–345. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrd JA, Caldwell DY, Nisbet DJ. 2017. The identification of fungi collected from the ceca of commercial poultry. Poult Sci 96:2360–2365. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danzeisen JL, Calvert AJ, Noll SL, McComb B, Sherwood JS, Logue CM, Johnson TJ. 2013. Succession of the turkey gastrointestinal bacterial microbiome related to weight gain. PeerJ 1:e237. doi: 10.7717/peerj.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oakley BB, Kogut MH. 2016. Spatial and temporal changes in the broiler chicken cecal and fecal microbiomes and correlations of bacterial taxa with cytokine gene expression. Front Vet Sci 3:11. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2016.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao Y, Xiang Y, Zhou W, Chen J, Li K, Yang H. 2017. Microbial community mapping in intestinal tract of broiler chicken. Poult Sci 96:1387–1393. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ott SJ, Kuhbacher T, Musfeldt M, Rosenstiel P, Hellmig S, Rehman A, Drews O, Weichert W, Timmis KN, Schreiber S. 2008. Fungi and inflammatory bowel diseases: alterations of composition and diversity. Scand J Gastroenterol 43:831–841. doi: 10.1080/00365520801935434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Chen D, Yu B, He J, Zheng P, Mao X, Yu J, Luo J, Tian G, Huang Z, Luo Y. 2018. Fungi in gastrointestinal tracts of human and mice: from community to functions. Microb Ecol 75:821–829. doi: 10.1007/s00248-017-1105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kers JG, Velkers FC, Fischer EAJ, Hermes GDA, Stegeman JA, Smidt H. 2018. Host and environmental factors affecting the intestinal microbiota in chickens. Front Microbiol 9:235. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong TS, Gupta A. 2019. Influence of early life, diet, and the environment on the microbiome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 17:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbott SP, Sigler L, Currah RS. 1998. Microascus brevicaulis sp. nov., the teleomorph of Scopulariopsis brevicaulis, supports placement of Scopulariopsis with the Microascaceae. Mycologia 90:297–302. doi: 10.2307/3761306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colombo AL, Padovan AC, Chaves GM. 2011. Current knowledge of Trichosporon spp. and Trichosporonosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 24:682–700. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00003-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugui JA, Kwon-Chung KJ, Juvvadi PR, Latgé J-P, Steinbach WJ. 2014. Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5:a019786. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubka V, Kolarik M, Kubatova A, Peterson SW. 2013. Taxonomic revision of Eurotium and transfer of species to Aspergillus. Mycologia 105:912–937. doi: 10.3852/12-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munkvold GP. 2003. Cultural and genetic approaches to managing mycotoxins in maize. Annu Rev Phytopathol 41:99–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052002.095510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar A, Henrissat B, Arvas M, Syed MF, Thieme N, Benz JP, Sorensen JL, Record E, Poggeler S, Kempken F. 2015. De novo assembly and genome analyses of the marine-derived Scopulariopsis brevicaulis strain LF580 unravels life-style traits and anticancerous scopularide biosynthetic gene cluster. PLoS One 10:e0140398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwen PC, Schutte SD, Florescu DF, Noel-Hurst RK, Sigler L. 2012. Invasive Scopulariopsis brevicaulis infection in an immunocompromised patient and review of prior cases caused by Scopulariopsis and Microascus species. Med Mycol 50:561–569. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.675629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandoval-Denis M, Sutton DA, Fothergill AW, Cano-Lira J, Gené J, Decock CA, de Hoog GS, Guarro J. 2013. Scopulariopsis, a poorly known opportunistic fungus: spectrum of species in clinical samples and in vitro responses to antifungal drugs. J Clin Microbiol 51:3937–3943. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01927-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi JH, Kim GB, Cha CJ. 2014. Spatial heterogeneity and stability of bacterial community in the gastrointestinal tracts of broiler chickens. Poult Sci 93:1942–1950. doi: 10.3382/ps.2014-03974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hallen-Adams HE, Suhr MJ. 2017. Fungi in the healthy human gastrointestinal tract. Virulence 8:352–358. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1247140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strati F, Di Paola M, Stefanini I, Albanese D, Rizzetto L, Lionetti P, Calabro A, Jousson O, Donati C, Cavalieri D, De Filippo C. 2016. Age and gender affect the composition of fungal population of the human gastrointestinal tract. Front Microbiol 7:1227. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crisol-Martínez E, Stanley D, Geier MS, Hughes RJ, Moore RJ. 2017. Understanding the mechanisms of zinc bacitracin and avilamycin on animal production: linking gut microbiota and growth performance in chickens. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:4547–4559. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park SH, Lee SI, Kim SA, Christensen K, Ricke SC. 2017. Comparison of antibiotic supplementation versus a yeast-based prebiotic on the cecal microbiome of commercial broilers. PLoS One 12:e0182805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pourabedin M, Guan L, Zhao X. 2015. Xylo-oligosaccharides and virginiamycin differentially modulate gut microbial composition in chickens. Microbiome 3:15. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pourabedin M, Xu Z, Baurhoo B, Chevaux E, Zhao X. 2014. Effects of mannan oligosaccharide and virginiamycin on the cecal microbial community and intestinal morphology of chickens raised under suboptimal conditions. Can J Microbiol 60:255–266. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2013-0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becattini S, Taur Y, Pamer EG. 2016. Antibiotic-induced changes in the intestinal microbiota and disease. Trends Mol Med 22:458–478. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Butaye P, Devriese LA, Haesebrouck F. 2003. Antimicrobial growth promoters used in animal feed: effects of less well known antibiotics on gram-positive bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 16:175–188. doi: 10.1128/cmr.16.2.175-188.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samonis G, Gikas A, Anaissie EJ, Vrenzos G, Maraki S, Tselentis Y, Bodey GP. 1993. Prospective evaluation of effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics on gastrointestinal yeast colonization of humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 37:51–53. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dollive S, Chen YY, Grunberg S, Bittinger K, Hoffmann C, Vandivier L, Cuff C, Lewis JD, Wu GD, Bushman FD. 2013. Fungi of the murine gut: episodic variation and proliferation during antibiotic treatment. PLoS One 8:e71806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Rosenvinge EC, Song Y, White JR, Maddox C, Blanchard T, Fricke WF. 2013. Immune status, antibiotic medication and pH are associated with changes in the stomach fluid microbiota. ISME J 7:1354–1366. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amir A, McDonald D, Navas-Molina JA, Kopylova E, Morton JT, Zech Xu Z, Kightley EP, Thompson LR, Hyde ER, Gonzalez A, Knight R. 2017. Deblur rapidly resolves single-nucleotide community sequence patterns. mSystems 2:e00191-16. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00191-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, Alexander H, Alm EJ, Arumugam M, Asnicar F, Bai Y, Bisanz JE, Bittinger K, Brejnrod A, Brislawn CJ, Brown CT, Callahan BJ, Caraballo-Rodríguez AM, Chase J, Cope EK, Da Silva R, Diener C, Dorrestein PC, Douglas GM, Durall DM, Duvallet C, Edwardson CF, Ernst M, Estaki M, Fouquier J, Gauglitz JM, Gibbons SM, Gibson DL, Gonzalez A, Gorlick K, Guo J, Hillmann B, Holmes S, Holste H, Huttenhower C, Huttley GA, Janssen S, Jarmusch AK, Jiang L, Kaehler BD, Kang KB, Keefe CR, Keim P, Kelley ST, Knights D, et al. 2019. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 37:852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deshpande V, Wang Q, Greenfield P, Charleston M, Porras-Alfaro A, Kuske CR, Cole JR, Midgley DJ, Nai TD. 2016. Fungal identification using a Bayesian classifier and the Warcup training set of internal transcribed spacer sequences. Mycologia 108:1–5. doi: 10.3852/14-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. 2007. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paulson JN, Stine OC, Bravo HC, Pop M. 2013. Differential abundance analysis for microbial marker-gene surveys. Nat Methods 10:1200–1202. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.R Core Team. 2018. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 59.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. 2013. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wickham H. 2016. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.