Abstract

Background

Plants have evolved a panoply of specialized metabolites that increase their environmental fitness. Two examples are caffeine, a purine psychotropic alkaloid, and crocins, a group of glycosylated apocarotenoid pigments. Both classes of compounds are found in a handful of distantly related plant genera (Coffea, Camellia, Paullinia, and Ilex for caffeine; Crocus, Buddleja, and Gardenia for crocins) wherein they presumably evolved through convergent evolution. The closely related Coffea and Gardenia genera belong to the Rubiaceae family and synthesize, respectively, caffeine and crocins in their fruits.

Results

Here, we report a chromosomal-level genome assembly of Gardenia jasminoides, a crocin-producing species, obtained using Oxford Nanopore sequencing and Hi-C technology. Through genomic and functional assays, we completely deciphered for the first time in any plant the dedicated pathway of crocin biosynthesis. Through comparative analyses with Coffea canephora and other eudicot genomes, we show that Coffea caffeine synthases and the first dedicated gene in the Gardenia crocin pathway, GjCCD4a, evolved through recent tandem gene duplications in the two different genera, respectively. In contrast, genes encoding later steps of the Gardenia crocin pathway, ALDH and UGT, evolved through more ancient gene duplications and were presumably recruited into the crocin biosynthetic pathway only after the evolution of the GjCCD4a gene.

Conclusions

This study shows duplication-based divergent evolution within the coffee family (Rubiaceae) of two characteristic secondary metabolic pathways, caffeine and crocin biosynthesis, from a common ancestor that possessed neither complete pathway. These findings provide significant insights on the role of tandem duplications in the evolution of plant specialized metabolism.

Keywords: Crocin biosynthesis, Caffeine biosynthesis, Gardenia jasminoides, Coffea canephora, Genomics, Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases, Aldehyde dehydrogenases, UDP-glucosyltransferases, N-Methyltransferases

Background

Flowering plants have evolved a diverse array of secondary metabolites to repel pathogens and predators, attract pollinators, and drive ecosystem functions. In many cases, the genomic context for the evolution of specialized plant compounds involves tightly linked clusters of genes, usually containing nonhomologous gene families, that together control novel biosynthetic pathways [1–3]. A few important metabolic clusters involve only tandem duplicates within single gene families, such as the N-methyltransferase (NMT) genes that control caffeine biosynthesis in the coffee plant [4], and the cytochrome p450 genes encoding the 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (DIMBOA) metabolic cluster of maize, which produces an important defense compound [5, 6]. Tandem gene duplicate clusters originally arise as copy number variants (CNVs) in populations that later become fixed within species by evolving split or novel functions [7]. Given the ongoing nature of CNV production during evolution, genome sequencing of closely related plants harboring distinct secondary metabolite profiles holds great promise for understanding the stepwise evolution of important tandem duplicate clusters.

The Gardenia genus, which is among the most commonly grown horticultural plants worldwide and is valued for the strong, sweet fragrance of its flowers, belongs to the family Rubiaceae. In this large family of angiosperms, only the Coffea canephora (robusta coffee) genome has been sequenced to date [4]. The Chinese species Gardenia jasminoides (gardenia) has been cultivated for at least 1000 years and was introduced to Europe and America in the mid-eighteenth century. The fruits of G. jasminoides, whose major bioactive constituents are genipin and crocins, were used as an imperial dye for royal costumes during the Qin and Han dynasties in China and are recorded in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia [8, 9]. Unlike coffee, gardenia does not accumulate caffeine. However, in a pattern similar to the scattered instances of convergent caffeine biosynthesis among several angiosperm families [4, 10], crocins are found in the flowers of the distantly related plants Buddleja davidii (Buddlejaceae) and in the stigmas of Crocus sativus (saffron) (Iridaceae) (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Crocin biosynthesis. a Simplified angiosperm phylogenetic tree. Crocin-synthesizing genera are shown in red (Gardenia), green (Buddleja), and purple (Crocus), and caffeine-synthesizing genera (Coffea) in brown. The red dot marks the divergence of Coffea and Gardenia. The divergence time between G. jasminoides and C. canephora was estimated at approximately 20.69 MYA. b Crocin accumulation in different G. jasminoides organs. R, root; St, stem; L, leaf; Fl, flower; Frl, fruitlet; GF, green fruit; RF, red fruit; Sa, sarcocarp

Apocarotenoids, derived from carotenoids by oxidative cleavage [11–13], play crucial roles in plants as signaling molecules, flower and fruit pigments, and regulators of membrane fluidity [14]. They have been reported to have anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-diabetic activities and to be beneficial in the treatment of central nervous system and cardiovascular diseases [15, 16]. Crocin biosynthesis in saffron stigmas is initiated by carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 2 (CsCCD2), which cleaves zeaxanthin to produce crocetin dialdehyde [17]. The aldehyde dehydrogenase CsALDH3I1 and the UDP-glucosyltransferase CsUGT74AD1 perform, respectively, the dehydrogenation of crocetin dialdehyde to crocetin and its glycosylation to crocins 1 and 2′ [18]. The UGT mediating the formation of more highly glycosylated crocins is still uncharacterized [18]. In Buddleja flowers, only the zeaxanthin cleavage step has been characterized, and it is mediated by BdCCD4.1 and BdCCD4.3 [19]. Thus, it appears that crocin biosynthesis in eudicots (Buddleja) and monocots (Crocus) has evolved through the convergent evolution of different CCD subclasses (CCD2 and CCD4, respectively) that have acquired the capacity to cleave zeaxanthin at the at the 7/8,7′/8′ positions to produce crocetin dialdehyde.

In G. jasminoides, crocins are accumulated in green and red fruits (Fig. 1b). The Gardenia crocin biosynthesis pathway has not yet been elucidated, in spite of the availability of transcriptome data [20]. Two G. jasminoides UGTs, GjUGT94E5 and GjUGT75L6, are able to catalyze the two-step conversion of crocetin into crocins in vitro [21]. However, the expression profiles of the corresponding genes are not consistent with their proposed role in crocin biosynthesis in G. jasminoides fruits [20]. Additionally, the lack of genomic information for crocin-producing species hampers the elucidation of the mechanisms underlying the molecular evolution of crocin biosynthesis. Recently, sequencing of the C. canephora (Rubiaceae) and Camellia sinensis (Theaceae) genomes has shown that the synthesis of caffeine, a purine alkaloid, has evolved independently in the two genera through tandem duplication and neofunctionalization of different N-methyltransferase (NMT) ancestral genes [4].

Here, we report a chromosome-level assembly of the highly heterozygous G. jasminoides genome, using a combination of Illumina short reads, Oxford Nanopore (ONT) long reads, and Hi-C scaffolding. The genes involved in the crocin biosynthesis pathway were identified through functional assays, and the molecular evolution of crocin and caffeine biosynthesis in the Rubiaceae family was clarified through comparative genomic studies.

Results

Chromosome-level assembly of the G. jasminoides genome (Additional file 1)

The size of the G. jasminoides genome was predicted to be 550.6 ± 9 Mb (± SD) based on flow cytometry and 547.5 Mb based on 17 k-mer distribution analysis and to show a very high level (about 2.2%) of heterozygosity (Additional file 2: Fig. S1). A highly collapsed and fragmented genome was assembled by ALLPATHS-LG using Illumina shotgun reads (293× coverage) (Additional file 2: Table S1). This assembly was 635.6 Mb in size (28% of N bases) and was composed of 58,859 scaffolds (N50, 60.6 kb) (Additional file 2: Table S3).

To improve the contiguity of the assembly, we generated 2,675,530 Oxford Nanopore (ONT) long reads with an N50 of 21.6 kb. The longest reads were 366.8 kb, and the genome coverage was about 60× (Additional file 2: Table S2). After testing different de novo assembly pipelines, we identified a package (Canu-SMARTdenovo-3×Pilon) that yielded satisfactory results (Additional file 2: Table S3). A contiguous assembly of 677.9 Mb with a contig N50 of 703.1 kb was produced, and the longest contig in the assembly was 11.7 Mb. Since the assembly size was larger than predicted genome size, we ran Purge Haplotigs to collapse the highly heterozygous regions. The purged assembly was 534.1 Mb long with a contig N50 of 1.0 Mb (Additional file 2: Table S3). The completeness of the genome assembly was assessed with the BUSCO pipeline, which found 95.0% complete BUSCOs, of which 92.7% were single-copy and 2.3% duplicated (Additional file 2: Table S3).

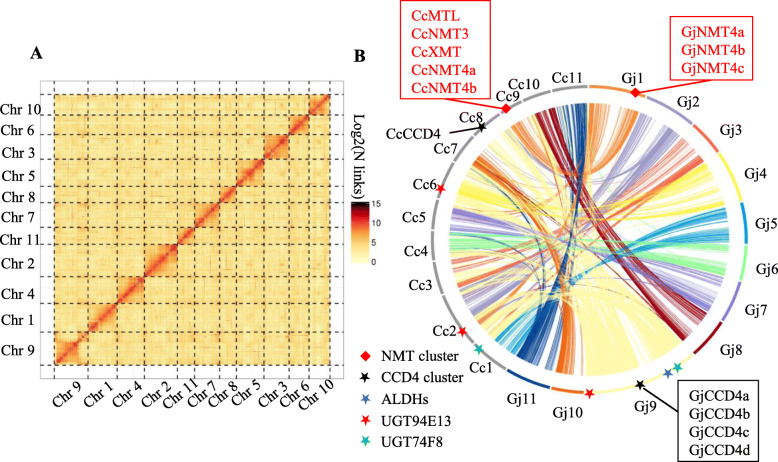

The contiguity of the assembly was further improved using Hi-C scaffolding. There were 56,933,122 paired-end reads representing valid interactions were used to scaffold 99.5% of the assembly into 11 chromosomes using the Lachesis package [22] (Fig. 2a). The final corrected chromosome-level genome was 535 Mb in size, 531 of which were assembled in the 11 chromosomes (Table 1). The G. jasminoides chromosomes showed a significant level of synteny with their C. canephora counterparts, with a limited number of translocations between the two genomes (Fig. 2b, Additional file 2: Fig. S2). In addition, a 154,919-bp chloroplast genome and 640,334-bp mitochondrial genome of G. jasminoides were assembled and identified.

Fig. 2.

The G. jasminoides genome. a Chromosome-level assembly of the G. jasminoides genome using Hi-C technology. b Synteny between C. canephora and G. jasminoides chromosomes. The positions of NMT genes, catalyzing caffeine biosynthesis in Coffea, and of CCD, ALDH, and UGT genes, catalyzing crocin biosynthesis in Gardenia, are marked

Table 1.

Metrics of the final assembly and annotation of the G. jasminoides genome

| Assembly size | 535 Mb |

| N50 | 44 Mb |

| No. of chromosomes | 11 |

| Assembly in chromosomes | 531 Mb |

| Assembly in unanchored contigs | 4 Mb |

| BUSCOs in assembly | 95.8% (S, 92.7%; D, 2.3%; F, 0.8%) |

| No. of genes | 35,967 |

| No. of genes in chromosomes | 35,779 |

| No. of genes in unanchored contigs | 188 |

| BUSCOs in annotation | 96.5% (S, 87.9%; D, 2.1%; F, 6.5%) |

Genome annotation and phylogenetic analysis

The G. jasminoides genome comprises 35,967 protein-coding genes (Table 1). Consistent with the assessment of genome assembly quality, orthologs of 96.5% of eukaryotic BUSCOs were identified in the G. jasminoides gene sets (Table 1). Transposable elements (TEs) account for approximately 54.0% (288,723,343 nt) of the G. jasminoides genome (Additional file 2: Table S4, 5, 6), and 62.2% of these TEs are long terminal repeat (LTR) elements. We identified 1798 full-length LTR elements including 709 Gypsy and 403 Copia elements. These elements have an average insertion time of 1.4 million years ago (MYA) assuming a mutation rate of μ = 1.3 × 10−8 (per bp per year) [23, 24] (Additional file 2: Fig. S3), and Gypsy elements are much younger than Copia elements (1.2 MYA vs 1.7 MYA, P < 0.05). Most 5s rRNAs are tandemly arrayed in Chr 11 of the G. jasminoides genome, and the tandem repeats of 18s rRNAs (average size of 1.8 kb), 5.8s rRNA (average size of 154 bp), and 28s rRNAs (average size of 6.3 kb) were clustered in Gardenia 10, spanning 65.9 kb (Additional file 2: Table S7, 8).

34,662 orthologous gene groups were found for G. jasminoides and 10 additional angiosperms, covering 335,254 genes in total. Among these, 155,220 genes clustering into 6671 groups were conserved in all plants examined, and 1248 gene families containing 5123 genes appeared to be unique to G. jasminoides (Additional file 2: Fig. S4A). Eight hundred ninety-one gene families were expanded, and 2666 gene families were contracted in the G. jasminoides lineage (Additional file 2: Fig. S4A). G. jasminoides-specific and expanded gene families comprised glycoside hydrolases (PF00232) and UDP-glucosyl/glucuronosyl transferases (PF00201), which might be related to the metabolism of bioactive compounds such as crocins and geniposides (Additional file 2: Table S9). Based on phylogenomic analysis of 121 single-copy genes, the divergence time between G. jasminoides and C. canephora was estimated at approximately 20.7 MYA (Fig. 1a, Additional file 2: Fig. S4B).

Identification of G. jasminoides candidate crocin biosynthetic genes (Additional file 3)

The mature fruit of G. jasminoides exhibits a visible reddish yellow or brown color, due to the presence of crocins, crocetin, and geniposides [21, 25, 26], which are found in the mature pericarp and sarcocarp of the fruit (Fig. 1b). We collected samples from three different fruit developmental stages: fruitlet with a green pericarp and immature sarcocarp, green fruit with a green pericarp and red sarcocarp, and red fruit with red pericarp and red sarcocarp. Analysis of different organs and tissues, including the root, stem, leaf, flower, fruitlet, green fruit, and red fruit, indicated that crocins are specifically localized in green and red fruits, whose sarcocarps have matured (Fig. 1b, Additional file 2: Fig. S5-S6). Transcriptome reads from seven G. jasminoides organs were mapped to the assembled genome and annotated gene loci to calculate gene expression (fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped, FPKM). Genome-wide analysis of the G. jasminoides assembly identified fourteen CCD genes that might be involved in the tailoring of carotenoids for apocarotenoid formation (Additional file 2: Fig. S7, Additional file 2: Table S10). The GjCCD4 and GjCCD8 gene subfamilies were expanded in the G. jasminoides lineage (Additional file 2: Table S10). GjCCD4a was highly expressed in green and red fruits (FPKM > 1000), in accordance with the distribution of crocins, while GjCCD4a, GjCCD4c, and GjCCD4d were highly expressed in flowers (Additional file 2: Fig. S10, Additional file 2: Table S11). GjCCD4a (ARU08109.1) showed high amino acid sequence similarity to GjCCD4b (81%), GjCCD4c (81%), and GjCCD4d (77%), and the four genes were located on a single gene cluster on chr 9 (see below).

Eighteen G. jasminoides genes with similarity to aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs), which catalyze the oxidation of aldehydes [27], were identified and classified into 10 distinct subfamilies (Additional file 2: Fig. S8, Additional file 2: Table S12). In C. sativus, CsALDH3I1 is known to mediate with high efficiency the dehydrogenation of crocetin dialdehyde to crocetin [18]; however, expression of GjALDH3 genes was low in the fruit and thus inconsistent with the crocin distribution in G. jasminoides organs. Instead, GjALDH2C3 (KY631926.1) was highly expressed in green and red fruits and flowers (Additional file 2: Fig. S10, Additional file 2: Table S12).

Two hundred thirty-seven UGT genes were identified in the G. jasminoides genome and were classified into 19 subfamilies (Additional file 2: Fig. S9, Additional file 2: Table S13). More than 50% are members of the UGT79, UGT73, UGT85, and UGT94 groups. Eleven UGT genes were significantly expressed in green and red fruits (Fig. S10, Additional file 2: Table S13).

Elucidation of the G. jasminoides crocin biosynthetic pathway

We used expression in E. coli to test the activity of the candidate crocin biosynthetic genes identified by expression analysis. A strain co-transformed with pET32a-CCD4a and the zeaxanthin accumulation plasmid pACCAR25ΔcrtX showed discoloration, and a new product with a retention time and characteristic fragment ions ([M + H]+: m/z 297.1939) identical to that of the crocetin dialdehyde standard was observed (Fig. 3a, Additional file 2: Fig. S11).

Fig. 3.

Elucidation of the crocin biosynthesis pathway in G. jasminoides.a UPLC-DAD chromatograms (abs at 440 nm) of E. coli extracts expressing GjCCD4a. b–d UPLC-DAD chromatograms (abs at 440 nm) of in vitro reactions catalyzed by GjALDH2C3 (b), GjUGT74F8 (c), and GjUGT94E13 (d). St, standards; EV, empty vector; lyc, lycopene; β-car, β-carotene; zea, zeaxanthin; cro, crocetin; CD, crocetin dialdehyde; CS, crocetin semialdehyde; CrI–V, crocins I–V

In both Crocus and Buddleja, the substrate for crocetin dialdehyde formation is zeaxanthin [17, 19, 28] (Fig. 1b). Since lycopene and β-carotene are also possible substrates, we expressed GjCCD4a in E. coli strains accumulating these carotenoids. In both cases, we detected the formation of crocetin dialdehyde (Fig. 3a) and, in the case of β-carotene, also of the intermediate product 8′-apo-β-carotenal (Fig. 3a, Additional file 2: Fig. S12, Additional file 2: Table S14). In contrast, none of the other Gardenia or Coffea CCD4 proteins was able to cleave zeaxanthin or β-carotene (Additional file 2: Fig. S13). Protein structure modeling and docking analysis of GjCCD4a suggested the capacity to bind all three substrates, in accordance with its catalytic activity (Additional file 2: Fig. S14).

Next, we tested the ability of the purified GjALDH2C3 protein to catalyze in vitro the oxidation of crocetin dialdehyde. Incubation of crocetin dialdehyde with GjALDH2C3 yielded two new peaks, and the retention time (7.84 min) and characteristic fragment ions ([M + H]+: m/z 327.1605) of the most abundant peak were consistent with those of the crocetin standard. In addition, the intermediate product crocetin semialdehyde (8.68 min and [M + H]+: m/z 311.1686) was also detected (Fig. 3b, Additional file 2: Fig. S15).

As noted above, a large number of UGT genes are expressed in Gardenia fruits, and these are likely involved in the synthesis of several classes of glycosylated compounds in these organs. The enzymatic activities of twelve candidate UGTs were characterized in vitro using crocetin as a substrate (marked with an asterisk in Additional file 2: Table S13). Three UGTs, namely GjUGT74F8, GjUGT75L6, and GjUGT94E13, were able to glycosylate crocetin and/or crocins (Fig. 3c, d, Additional file 2: Fig. S16-S21). Of these, only two (GjUGT74F8 and GjUGT94E13) were expressed at high levels in fruits, suggesting that they are involved in crocin production, while the third, described previously [21], was not significantly expressed in these organs (Additional file 2: Fig. S10).

GjUGT74F8, which is the most highly expressed among all UGTs (Additional file 2: Fig. S10, Additional file 2: Table S13), is similar to CsUGT74AD1, which is responsible for crocin primary glycosylation in C. sativus [18, 29] (Additional file 2: Fig. S22). Upon in vitro incubation of GjUGT74F8 with crocetin, two new peaks with retention times of 4.96 and 6.30 min were detected. The newly formed products had the same fragmentation patterns as crocin III ([M + Na]+, 675.2620) and crocin V ([M + Na]+, 513.2090), respectively, demonstrating that GjUGT74F8 has the ability to add one or two β-d-glucoses to the carboxyl groups of crocetin (primary glycosylation) (Fig. 3c, Additional file 2: Fig. S20). In addition, reversible conversion of crocin II to crocin IV and vice versa was observed, suggesting that GjUGT74F8 possesses also a hydrolytic activity, able to remove a single β-d-glucose (Fig. 3c, Additional file 2: Fig. S20).

In vitro incubation of crocetin with purified GjUGT94E13 resulted in the generation of two new products with retention times of 4.22 and 5.75 min, respectively. These two compounds had mass spectra with [M + Na]+ peaks at m/z 999.3699 and 675.2610, respectively, consistent with those of crocin I and crocin IV (Fig. 3d, Additional file 2: Fig. S16). We also found that crocin IV was gradually converted to crocin I by the extension of the incubation time with GjUGT94E13 (Fig. 3d, Additional file 2: Fig. S16) and that GjUGT94E13 could efficiently catalyze the glycosylation of crocins II and III to crocin I (Fig. 3d, Additional file 2: Fig. S17, S18). In no case was generation of a crocin with a single β-d-glucosyl ester detected under different reaction conditions, suggesting that GjUGT94E13 could catalyze either the addition of a second glucosyl group to a pre-existing one (secondary glycosylation) or the sequential addition of two glucosyl groups to a carboxyl group (primary and secondary glycosylation).

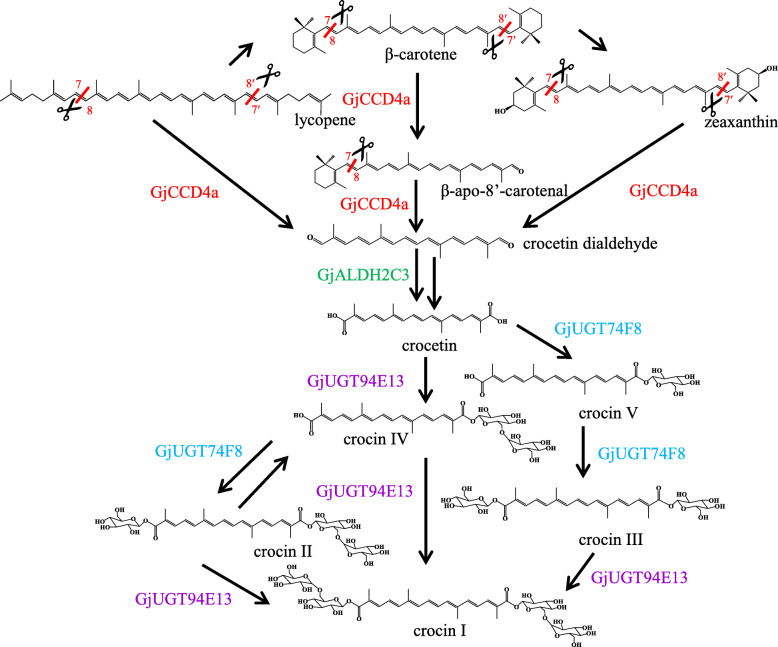

Based on these results, the complete crocin biosynthesis pathway in G. jasminoides is depicted in Fig. 4. Lycopene, β-carotene, and zeaxanthin are cleaved at the 7/8,7′/8′ positions by GjCCD4a, yielding crocetin dialdehyde, which is then converted to crocetin by GjADH2C3. Crocetin is the substrate of two UGTs, GJUGT74F8 and GjUGT94E13, adding respectively one or two glucose esters to the two carboxylic groups.

Fig. 4.

The crocin biosynthesis pathway in G. jasminoides

Evolution of crocin and caffeine biosynthesis genes in the Rubiaceae

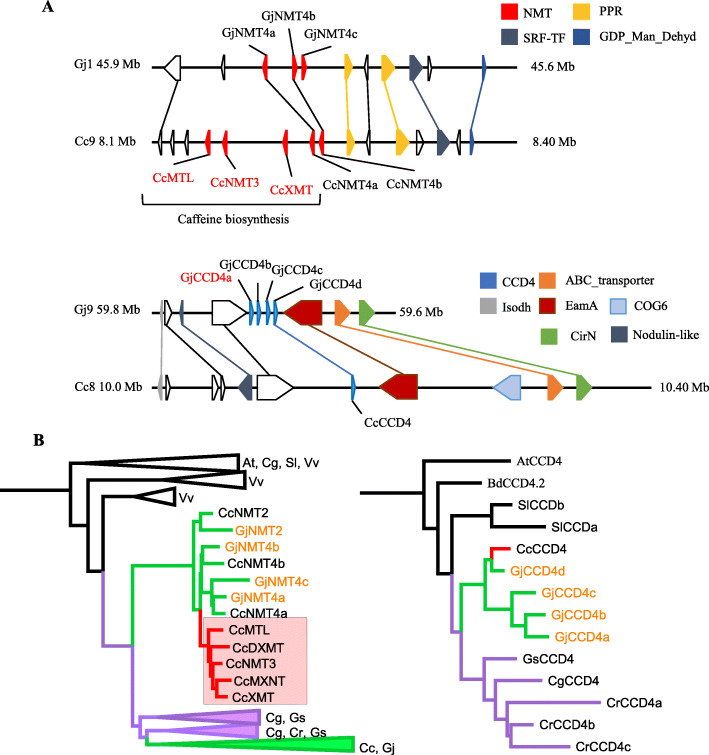

Synteny analysis demonstrated clearly that Coffea caffeine synthases and Gardenia CCD4a are localized, respectively, in tandemly repeated arrays that are unique to each of the two species, suggesting the two gene duplication series occurred after the Coffea-Gardenia divergence (Fig. 5a, Additional file 2: Fig. S23-24). The Coffea caffeine synthase gene cluster is syntenic to non-caffeine-producing NMTs in the Gardenia genome (Fig. 5a, Additional file 2: Fig. S23), while the close Gentianales relative Gelsemium (Gelsemiaceae) does not even contain NMTs in the homologous chromosomal regions. The latter observation suggests that the common ancestral genomic block in all gentianalean species lacked an NMT gene and that the ancestor of the future caffeine synthase cluster translocated there during Rubiaceae evolution, where it duplicated in Coffea only after the divergence of Coffea and Gardenia (Fig. 5b, Additional file 2: Fig. S24). Conversely, the Gardenia gene cluster comprising GjCCD4a-b-c-d is syntenic to a unique CCD4 gene in the coffee genome (Fig. 5a, Additional file 2: Table S15), yielding an inverted evolutionary scenario wherein local duplications in Gardenia that occurred after Coffea-Gardenia common ancestry led to the production of distinct bioactive compounds. In contrast, the downstream crocin biosynthesis genes GjALDH2C3, GjUGT74F8, and GjUGT94E5 are localized in gene clusters that appear conserved between Coffea and Gardenia (Additional file 2: Fig. S24), suggesting that they may have been generated before the split of the two genera.

Fig. 5.

Coffea caffeine synthases and Gardenia crocin biosynthesis dioxygenase arose through genus-specific tandem duplications. a Microsynteny between Coffea and Gardenia around the caffeine synthases of the former and the first dedicated gene in crocin biosynthesis in Gardenia, GjCCD4a. b Simplified phylogenies (pruned from the trees provided in Figs. S27-S28) depicting the evolution of caffeine and crocin biosynthetic genes in Gentianales. Purple branches indicate clades that are Gentianales-specific; green, Rubiaceae-specific; red, Coffea-specific. The gene IDs used for the phylogenetic trees of NMTs and CCD are the following: CcNMT2 (Cc02_g09350), CcNMT4b (Cc09_g07000), CcNMT4a (Cc09_g06990), CcMTL (Cc09_g06950), CcNMT3 (Cc09_g06960), CcXMT (Cc09_g06970), CcDXMT (Cc01_g00720), CcMXMT (Cc00_g24720), GjNMT2 (Gj9A1032T108), GjNMT4a (Gj1A458T26), GjNMT4b (Gj1X458T25), GjNMT4c (Gj1A458T28), SlCCD4a (Solyc08g075480.2.1), SlCCDb (Solyc08g075490.2.1), CcCCD4 (Cc08_g05610), GjCCD4a (Gj9A597T69), GjCCD4b (Gj9A597T68), GjCCD4c (Gj9A597T67), GjCCD4d (Gj9P597T6), GsCCD4 (Gs_scaff312_1.38), CrCCD4a (CRO_T140281), CrCCD4b (CRO_T140282), CrCCD4c (CRO_T140277), and CgCCD4 (cal_g006885.t1). Gene IDs for those with the biochemical activities in question are shown in red. Gardenia gene IDs are shown in orange. All other gene IDs are shown in black. For the collapsed tree branches in the pruned trees, species abbreviations are as follows: At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Vv, Vitis vinifera; Sl, Solanum lycopersicum; Gs, Gelsemium sempervirens; Cr, Catharanthus roseus; Cg, Calotropis gigantea; Cc, Coffea canephora; Gj, Gardenia jasminoides; Bd, Buddleja davidii

Phylogenetic analyses of NMTs related to caffeine synthases and CCDs related to crocin synthase confirmed this evidence based on synteny. Caffeine biosynthetic enzymes belong to a lineage of NMTs that are specific to Rubiaceae, however, ones that duplicated and specifically evolved caffeine biosynthetic function only in Coffea (Fig. 5b, Additional file 2: Fig. S26, Additional file 4: Fig. S27). Similarly, the CCD4 subfamily wherein Gardenia’s crocin synthase resides is Rubiaceae-specific, but not tandemly duplicated in Coffea as it is in Gardenia (Fig. 5b, Additional file 5: Fig. S28). The UGT74 and UGT94 gene subfamilies in both Rubiaceae species are contained within distinct subclades in a large UGT family tree, each grouping with related genes from other Gentianales in sublineages likely to be of ancient origin (Additional file 6: Fig. S29). Similarly, the ALDH2 genes of Coffea and Gardenia are close relatives in a subclade also comprising genes from other Gentianales species (Additional file 7: Fig. S30).

Discussion

Chromosome-level assembly of a highly heterozygous genome

Many plants including medicinal ones such as Salvia miltiorrhiza [30], Panax ginseng [31], Panax notoginseng [32, 33], and Glycyrrhiza uralensis [34] are highly heterozygous, resulting in fragmented genome assemblies when using traditional short read methods. G. jasminoides, the second plant of Rubiaceae with a sequenced genome, is self-incompatible with high (2.2%) heterozygosity. We developed an efficient method to produce chromosome-level assemblies for heterozygous plant genomes using a combination of short Illumina and long ONT reads and Hi-C scaffolding [22, 35, 36]. The assemblies constructed using short reads were extremely fragmented, while the combination of short and ONT reads with a Canu-SMARTdenovo assembly pipeline produced a G. jasminoides assembly with the highest contiguity. The significant difference in the number of annotated repeat sequences between the ONT (53.97%) and Illumina (36.51%)-based assemblies indicates the importance of genome contiguity for annotation of repetitive elements (Additional file 2: Table S3). However, the ONT-based assembly size was much larger than the genome size predicted by k-mer distribution and flow cytometry, suggesting that highly divergent haplotypes were assembled separately. This was confirmed and corrected by haplotig purging, whereafter the assembly was scaffolded into chromosomal pseudomolecules using Hi-C. Given the low cost of ONT long reads, the pipeline described here provides an extremely cost-effective method for producing chromosome-level assemblies of highly heterozygous plant genomes.

Characterization of the Gardenia crocin biosynthetic pathway

In a previous transcriptomic study [20], we identified several G. jasminoides unigenes bearing high sequence similarity to candidate genes for crocin biosynthesis (Additional file 2: Table S16). However, the low number of tissues analyzed by RNA-Seq (3 versus 7 in the present study) and the high level of fragmentation of the unigenes prevented the unambiguous identification of bona fide candidates for all the steps through co-expression analysis, as well as the expression in E. coli of the corresponding full-length proteins for functional assays. Based on genome-wide candidate gene identification, expression studies, and in vitro functional studies, three of the 7 previously identified unigenes (GjCCD4a, GjALDH2C3, and UGT94E13), but also a novel UGT74F8 gene, which went undetected in the previous transcriptome analysis, were shown to be involved in crocin biosynthesis in G. jasminoides.

In C. sativus, zeaxanthin is cleaved symmetrically at the 7/8,7′/8′ positions by CsCCD2 to produce crocetin dialdehyde [17, 28], while, in B. davidii, the same reaction is carried out by BdCCD4.1 and BdCCD4.3 [19]; no activity of CsCCD2 and/or BdCCD4.1/BdCCD4.3 on other carotenoids, including β-carotene and lycopene, has been reported. GjCCD4a from G. jasminoides shares only 31% identity with CsCCD2, but 56 and 59% identity with BdCCD4.1 and BdCCD4.3, respectively, and can catalyze the symmetric 7/8,7′/8′ cleavage of zeaxanthin, β-carotene, and lycopene to produce crocetin dialdehyde. Thus, crocetin biosynthesis evolved in different plant taxa through convergent evolution, since the carotenoid cleavage step is catalyzed by a CCD2 in Crocus [17], but by CCD4 enzymes in Buddleja [19] and Gardenia (this paper). Convergent evolution also underlies the second step of crocin biosynthesis, which is mediated by an ALDH3 in C. sativus [18] and by an ALDH2 in G. jasminoides (this paper).

Two Gardenia UGTs, GjUGT75L6 and GjUGT94E5, were previously shown to catalyze the conversion of crocetin to crocins in vitro [21]. However, their low expression in fruits suggests that they are not the primary enzymes involved in crocin biosynthesis in vivo. We identified two novel UGT genes, GjUGT74F8 and GjUGT94E13, closely related to GjUGT75L6 and GjUGT94E5 that are highly expressed in fruits and show co-expression with GjCCD4a. GjUGT74F8 was the most highly expressed UGT gene in mature fruit, and the protein product catalyzed the primary glycosylation of crocetin, the same reaction catalyzed by GjUGT75L6 [21] and by Crocus UGT74AD1 [18]. Similar to the latter, GjUGT74F8 did not exhibit a secondary glycosylation activity. GjUGT74F8 was also found to catalyze de-glycosylation reactions. Reversible glycosylation has been previously described in other plant UGTs [37]. GjUGT94E13 catalyzed primary and secondary glycosylation of crocetin to form crocins IV and I, presumably via the sequential addition of two β-d-glucosyl esters. Crocins V and II were undetectable when crocetin was incubated with GjUGT94E13, suggesting that the secondary glycosylation step occurred much faster than the primary glycosylation one. Incubation of crocin II or crocin III with GjUGT94E13 resulted in the complete conversion to crocin I, confirming that GjUGT94E13 is able to add a second glucosyl moiety to a mono-glycosyl group (secondary glycosylation).

Molecular evolution of caffeine and crocin biosynthesis in the Rubiaceae

The chromosome-level Gardenia genome assembly reported here and its comparative analysis with the closely related Coffea genome [4] allowed a detailed reconstruction of the molecular events that led to the evolution of the caffeine and crocin pathways in the two genera. The NMT gene cluster involved in caffeine biosynthesis in C. canephora shows synteny to a region in G. jasminoides that also contains NMTs, but ones that predate the evolution of the caffeine synthase cluster characteristic of coffee. Conversely, the first dedicated gene in crocin biosynthesis, GjCCD4a, is part of a 4-gene cluster for which, in coffee, there is only one ortholog (Cc08g05610), showing the highest identity (80.8%) to GjCCD4c. The two genes are highly expressed in flowers in the two species, suggesting that they may be responsible for carotenoid cleavage in the white flowers of G. jasminoides and C. canephora, followed by volatile apocarotenoid formation [38]. Additionally, neither the CcCCD4 nor the GjCCD4b-c proteins exhibit 7/8,7′/8′ cleavage activity against any carotenoid tested. These findings suggest that caffeine and crocetin biosynthesis in coffee and Gardenia evolved, respectively, through tandem duplications and functional specialization of NMT and CCD4 genes, and that these tandem duplications occurred after the separation of the two genera. Besides giving rise to novel metabolic functions, tandem gene duplications play several additional roles in genome evolution; for instance, in the birch and avocado genomes, tandem duplicates are enriched for pathogen responses [7, 39], while in the Australian carnivorous pitcher plant, tandem duplicates are enriched in enzymatic functions related to the acquisition of carnivory [40]. The production of tandem duplicates as copy number variants in populations, and their subsequent species-level fixation, provides a general evolutionary substrate for novel secondary metabolic activities in the recent adaptive landscapes of plant genomes.

Conclusion

This study sequenced the genome of G. jasminoides, a crocin-producing species, and dissected the complete crocin biosynthetic pathway through genomic and functional assays. Comparative analyses with C. canephora revealed that the caffeine biosynthetic genes (NMTs) in Coffea and the first dedicated crocin biosynthetic gene (GjCCD4a) in Gardenia evolved through recent tandem gene duplications in the two different genera, respectively. This study highlighted the divergent evolution of caffeine and crocin biosynthesis within the coffee family, providing significant insights on the role of tandem duplications in the evolution of plant specialized metabolism.

Methods

Plant materials

An individual G. jasminoides (line 1–9) plant, which was asexually propagated by cutting, was obtained from Nanchuan District (29° N and 107° E), Chongqing City, China. Seven independent organs from G. jasminoides, including the root, stem, leaf, flower, fruitlet, green fruit, and red fruit, were collected. The fruitlet, green fruit, and red fruit represented different maturity. In total, 21 samples including three biological replicates for each organ were gathered. All samples were divided into two portions, which were used for the measurement of crocin content and RNA sequencing. The pooled young leaves were used to DNA extraction for Illumina and ONT sequencing.

ONT sequencing and assembly

Following the methods for megabase-size DNA preparation, we extracted the high molecular weight (HMW) genomic DNA of G. jasminoides, which was used to construct paired-end, mate-pair, and ONT libraries. The HMW gDNA was randomly fragmented using a Megaruptor; then, the large fragments were selected and purified using BluePippin and AMPure beads. After end-prep, ligation of sequencing adapters, and tether attachment, the fragments were sequenced on the ONT GridION X5 platform with 6 nanopore flow cells (v9.4.1). Base calling was performed using the Oxford Nanopore base caller Guppy (v1.8.5). Canu (v1.7) was used to correct, trim, and assemble the ONT raw reads with the default parameters [41]. The correction-free approach, named Minimap/miniasm [42], was also independently performed with the recommended parameters. The assembler SMARTdenovo was also used for assembly with the corrected and trimmed ONT reads as input [43]. The Canu-SMARTdenovo contigs were polished three times with Pilon (v1.22) using Illumina short reads [44]. The final scaffolds were constructed with the polished contigs and corrected ONT reads using SSPACE-LongRead (version 1.1) [45], and heterozygous sequences were removed using Purge Haplotigs [46]. The quality of the genome assembly was estimated by searching for Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO v4.0, embryophyte profile) with Embryophya odb 10 dataset [47]. Illumina sequences from the G. jasminoides DNA and RNA libraries were mapped to evaluate the quality of the assembled genome using BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) [48].

Chromosome construction using Hi-C

Fresh tissue of G. jasminoides was used to construct a Hi-C sequencing library. Steps included chromatin crosslinking, chromatin digestion with Hind III, biotin labeling and end repair, DNA purification, streptavidin pull-down of labeled Hi-C ligation products, and construction of an Illumina sequencing library. The clean sequences were mapped to the draft genome, and valid Hi-C reads were used to correct the draft assembly. Then, the draft genome of G. jasminoides was assembled into chromosomes (2n = 22) using Lachesis [22].

Genome annotation and RNA-Seq analysis

Annotation of structural repeats in the G. jasminoides genome was performed using the RepeatModeler (http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler/; v1.0.9) package, which combines RECON and RepeatScout to identify and classify the repeat elements. The long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs) in G. jasminoides were identified using LTR_Finder (v1.0.6) and LTR_retriever with the default parameters [49]. The repeat sequences were masked by RepeatMasker (v4.0.6) (http://www.repeatmasker.org/).

RNA-Seq on the HiSeq 4000 platform was performed for 21 samples. The short reads were assembled de novo using Trinity (v 2.2.0) [50], and peptide sequences were predicted with TransDecoder (v2.1.0) (https://github.com/TransDecoder). The masked G. jasminoides genome annotation was ab initio predicted using the MAKER (v2.31.9) [51] annotation pipeline, integrating the assembled transcripts of G. jasminoides and protein sequences from G. jasminoides, C. canephora, and A. thaliana. Noncoding RNAs were annotated by aligning to the Rfam database using INFERNAL (v1.1.2) [52], and miRNAs were further analyzed by performing BLASTN searches against the miRNA database. The RNA-Seq reads from different G. jasminoides organs were aligned to the masked genome using HiSAT2 (v2.0.5), and the FPKM values of annotated genes in the reference genome were calculated using Cufflinks (v2.2.1) [53].

The amino acid sequences of proteins from G. jasminoides and nine other angiosperms were clustered into orthologous groups using OrthoMCL (version 2.0.9) [54]. Phylogenetic analyses of single-copy orthologous genes were performed using the RAxML package (version 8.1.13) using the JTT+G+I substitution model for amino acid sequences with 1000 bootstrap replicates [55]. Divergence times were directly estimated based on the divergence times of P. trichocarpa-G. max (94–127 MYA) and B. distachyon-Z. mays (40–53 MYA) obtained from TimeTree (http://www.timetree.org). The Markov Cluster Algorithm (MCL) was used to identify species-specific gene groups [56]. CAFÉ (version 3.1) was used to predict gene family expansion and contraction [57]. Genome synteny analyses were performed using the CoGe web suite, www.genomevolution.org, according to methods described elsewhere [58–60].

Identification of gene families related to crocin biosynthesis

Protein sequences of the CCD, ALDH, and UGT family members in A. thaliana were downloaded from the TAIR database, then were used as queries in BLASTP searches against the G. jasminoides protein sequences to identify homologous sequences. Full-length protein sequences were corrected and aligned with ClustalW2 [61]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum likelihood method with the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model and 1000 Bootstrap replicates [62]. Further analyses incorporated blast searches (using Gardenia proteins as queries) of a number of other genomes to identify more CCD, ALDH, and UGT genes. For NMTs, the Coffea canephora XMT protein was used as a query (NCBI accession ABD90685.1). Species considered were Gardenia jasminoides (CoGe genome ID 53980), Coffea canephora (CoGe genome ID 19443), Arabidopsis thaliana (CoGe genome ID 16911), Calotropis gigantea (CoGe genome ID 36623), Catharanthus roseus (CoGe genome ID 36703), Vitis vinifera (CoGe genome ID 19990), Gelsemium sempervirens (CoGe genome ID 53941), and Solanum lycopersicum (CoGe genome ID 12289). Gene model IDs from the respective CoGe-uploaded genomes were retained as leaf IDs for phylogenetic analysis, with the exception that “:” when it appeared in a gene model ID was replaced by “_”. Several additional anchoring protein sequences from NCBI were incorporated in the NMT tree (MTL,_AFV60456.1; DXMT,_ABD90686.1; MXMT,_AFV60445.1; XMT,_ABD90685.1). Searches were run on the CoGe platform using default parameters and saving 100 Blast HSPs per species. Unique translated sequences were then downloaded, duplicates were excluded using BBedit, sequences with internal stop codons were excluded, and then trees were run using PASTA [63] with MAFFT [64] to align the protein sequences and FastTree [65] to create an approximately maximum likelihood tree. Trees were visualized and edited using FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) (Additional file 4: Fig. S27, Additional file 5: Fig. S28, Additional file 6: Fig. S29, Additional file 7: Fig. S30). To interpret the supplemental figures, pink branches represent gentianalean clades, green branches represent Rubiaceae clades, and orange gene model IDs represent Gardenia genes. Coffee-specific clades are shown in red. In the NMT supplemental tree (Additional file 4: Fig. S27), the anchoring protein sequences are shown in red.

Enzymatic activity assays and LC/LC-MS analyses

The cDNAs of candidate genes from the CCD, ALDH, and UGT families were de novo synthesized and cloned into expression vectors via digestion and ligation (Additional file 2: Fig. S25). The GjALDH2C3, GjUGT94E13, and GjUGT74F8 proteins were purified from E. coli using affinity chromatography to a purity > 95% (Additional file 2: Fig. S15, S16, S19). The in bacterio and in vitro activity assays and detailed reaction mixtures are described in the Supplemental information. Crocetin dialdehyde (trans-crocetin dialdehyde) and crocetin (trans-crocetin) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) and CFW Laboratories (Germany), respectively. Crocin I and crocin II were purchased from Meilunbio (China). All the chemical reagents used here were of analytical grade.

Samples were analyzed using a Thermo Ultimate 3000 system equipped with an Acquity UPLC® BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 100 × 2.1 mm). A gradient elution procedure was applied, using the mobile phases acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid (A) and water containing 0.1% formic acid (B). The following gradient elution program was used at a flow rate 0.3 mL/min: 0–5 min, 10% A linearly increased to 50% A; 5–8 min, 50% A linearly increased to 90% A; 8–10 min, 90% A linearly increased to 100% A and sustained for 20 min; and 30–31 min, back to 10% A.

Qualitative analysis of each compound was carried out using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (Agilent Technologies 1290 Infinity II LC System and 6545 Q-TOF, with Dual Agilent Jet Stream Electrospray Ionization sources). The drying gas was set at 325 °C with a flow rate of 6 L/min, and the sheath gas was set at 350 °C, with a flow rate of 12.0 L/min. The nebulizer was set at 45 psig, and the VCap was set at 4000 V. The data were analyzed using MassHunter (version B.07.00). The detailed information of mentioned compounds was listed in Additional file 2: Table S17, S18.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments were performed on Bruker AV III 600 NMR spectrometer (600 MHz for 1H NMR and 150 MHz for 13C NMR) in CDCl3 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and the chemical shifts were given in δ (ppm) with TMS as the internal standard.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Detailed methods and results for genome sequencing.

Additional file 2: Figures S1-S26; Tables S1-S18.

Additional file 3. Detailed methods and results for crocin biosynthesis.

Additional file 4: Figure S27. Pasta phylogenetic tree of NMTs from different species.

Additional file 5: Figure S28. Pasta phylogenetic tree of CCDs from different species.

Additional file 6: Figure S29. Pasta phylogenetic tree of UGTs from different species.

Additional file 7: Figure S30. Pasta phylogenetic tree of ALDHs from different species.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Norihiko Misawa for providing plasmids of zeaxanthin, lycopene, and β-carotene production.

Authors’ contributions

Z.X. and J.S. designed and coordinated the study. Z.X., X.P., R.G., A.J., S.C., W.S., Z.W., J.S., T.G., C.X., H.Y., and T.X. generated the data. K.H. and F.R. supplied the plant materials. Z.X., X.P., R.G., C.H., J.K., O.D., S.F., M.R., V.A.A., and G.G. analyzed the data. Z.X., X.P., G.G., and J.S. wrote the manuscript. C.H., J.K., O.D., V.A., G.G., and S.C. revised the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973424) to Z.X., the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2016-I2M-3-016) to J.S., the EU grant DISCO (grant no. 613513) and Lazio Region project ProBioZaff (85-2017-15296) to G.G., and the US National Science Foundation (1442190) to V.A.A.

Availability of data and materials

G. jasminoides line 1–9 and the constructs used in this work can be obtained by writing to K.H. (email: 402632144@qq.com). Genome sequence and assembly data were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive from the NCBI under the accession number PRJNA477438 [66]. The assembled genomes including nuclear genome, chloroplast genome, and mitochondrial genome for G. jasminoides were submitted to the NCBI genome resource with accession no. VZDL00000000 [67], and the CoGe with id53980 [68], id55476 [69], and id55477 [70], respectively.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhichao Xu and Xiangdong Pu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Giovanni Giuliano, Email: giovanni.giuliano@enea.it.

Shilin Chen, Email: slchen@icmm.ac.cn.

Jingyuan Song, Email: jysong@implad.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12915-020-00795-3.

References

- 1.Nutzmann HW, Huang A, Osbourn A. Plant metabolic clusters - from genetics to genomics. New Phytol. 2016;211:771–789. doi: 10.1111/nph.13981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chae L, Kim T, Nilo-Poyanco R, Rhee SY. Genomic signatures of specialized metabolism in plants. Science. 2014;344:510–513. doi: 10.1126/science.1252076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo L, Winzer T, Yang X, Li Y, Ning Z, He Z, Teodor R, Lu Y, Bowser TA, Graham IA, Ye K. The opium poppy genome and morphinan production. Science. 2018;362:343–347. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denoeud F, Carretero-Paulet L, Dereeper A, Droc G, Guyot R, Pietrella M, Zheng C, Alberti A, Anthony F, Aprea G, et al. The coffee genome provides insight into the convergent evolution of caffeine biosynthesis. Science. 2014;345:1181–1184. doi: 10.1126/science.1255274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frey M, Chomet P, Glawischnig E, Stettner C, Grun S, Winklmair A, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Meeley RB, Briggs SP, et al. Analysis of a chemical plant defense mechanism in grasses. Science. 1997;277:696–699. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutartre L, Hilliou F, Feyereisen R. Phylogenomics of the benzoxazinoid biosynthetic pathway of Poaceae: gene duplications and origin of the Bx cluster. BMC Evol Biol. 2012;12:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salojarvi J, Smolander OP, Nieminen K, Rajaraman S, Safronov O, Safdari P, Lamminmaki A, Immanen J, Lan T, Tanskanen J, et al. Genome sequencing and population genomic analyses provide insights into the adaptive landscape of silver birch. Nat Genet. 2017;49:904–912. doi: 10.1038/ng.3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao W, Li S, Wang S, Ho CT. Chemistry and bioactivity of Gardenia jasminoides. J Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:43–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission . Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: China Medical Science and Technology Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang R, O'Donnell AJ, Barboline JJ, Barkman TJ. Convergent evolution of caffeine in plants by co-option of exapted ancestral enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:10613–10618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602575113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma G, Zhang L, Matsuta A, Matsutani K, Yamawaki K, Yahata M, Wahyudi A, Motohashi R, Kato M. Enzymatic formation of beta-citraurin from beta-cryptoxanthin and Zeaxanthin by carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase4 in the flavedo of citrus fruit. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:682–695. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.223297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang B, Liu C, Wang Y, Yao X, Wang F, Wu J, King GJ, Liu K. Disruption of a CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE 4 gene converts flower colour from white to yellow in Brassica species. New Phytol. 2015;206:1513–1526. doi: 10.1111/nph.13335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohmiya A, Kishimoto S, Aida R, Yoshioka S, Sumitomo K. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CmCCD4a) contributes to white color formation in chrysanthemum petals. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1193–1201. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.087130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou X, Rivers J, Leon P, McQuinn RP, Pogson BJ. Synthesis and function of apocarotenoid signals in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:792–803. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khorasanchi Z, Shafiee M, Kermanshahi F, Khazaei M, Ryzhikov M, Parizadeh MR, Kermanshahi B, Ferns GA, Avan A, Hassanian SM. Crocus sativus a natural food coloring and flavoring has potent anti-tumor properties. Phytomedicine. 2018;43:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair SC, Pannikar B, Panikkar KR. Antitumour activity of saffron (Crocus sativus) Cancer Lett. 1991;57:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(91)90203-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frusciante S, Diretto G, Bruno M, Ferrante P, Pietrella M, Prado-Cabrero A, Rubio-Moraga A, Beyer P, Gomez-Gomez L, Al-Babili S, Giuliano G. Novel carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase catalyzes the first dedicated step in saffron crocin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12246–12251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404629111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demurtas OC, Frusciante S, Ferrante P, Diretto G, Azad NH, Pietrella M, Aprea G, Taddei AR, Romano E, Mi J, et al. Candidate enzymes for saffron crocin biosynthesis are localized in multiple cellular compartments. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:990–1006. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahrazem O, Diretto G, Argandona J, Rubio-Moraga A, Julve JM, Orzaez D, Granell A, Gomez-Gomez L. Evolutionarily distinct carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases are responsible for crocetin production in Buddleja davidii. J Exp Bot. 2017;68:4663–4677. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji A, Jia J, Xu Z, Li Y, Bi W, Ren F, He C, Liu J, Hu K, Song J. Transcriptome-guided mining of genes involved in crocin biosynthesis. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:518. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagatoshi M, Terasaka K, Owaki M, Sota M, Inukai T, Nagatsu A, Mizukami H. UGT75L6 and UGT94E5 mediate sequential glucosylation of crocetin to crocin in Gardenia jasminoides. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belton JM, McCord RP, Gibcus JH, Naumova N, Zhan Y, Dekker J. Hi-C. a comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods. 2012;58:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Z, Xin T, Bartels D, Li Y, Gu W, Yao H, Liu S, Yu H, Pu X, Zhou J, et al. Genome analysis of the ancient tracheophyte Selaginella tamariscina reveals evolutionary features relevant to the acquisition of desiccation tolerance. Mol Plant. 2018;11:983–994. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VanBuren R, Wai CM, Ou S, Pardo J, Bryant D, Jiang N, Mockler TC, Edger P, Michael TP. Extreme haplotype variation in the desiccation-tolerant clubmoss Selaginella lepidophylla. Nat Commun. 2018;9:13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02546-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao L, Zhu BY. The accumulation of crocin and geniposide and transcripts of phytoene synthase during maturation of Gardenia jasminoides fruit. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:686351. doi: 10.1155/2013/686351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Zhang H, Li YX, Cai L, Huang J, Zhao C, Jia L, Buchanan R, Yang T, Jiang LJ. Crocin and geniposide profiles and radical scavenging activity of gardenia fruits (Gardenia jasminoides Ellis) from different cultivars and at the various stages of maturation. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brocker C, Vasiliou M, Carpenter S, Carpenter C, Zhang Y, Wang X, Kotchoni SO, Wood AJ, Kirch HH, Kopecny D, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) superfamily in plants: gene nomenclature and comparative genomics. Planta. 2013;237:189–210. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1749-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahrazem O, Rubio-Moraga A, Berman J, Capell T, Christou P, Zhu C, Gomez-Gomez L. The carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase CCD2 catalysing the synthesis of crocetin in spring crocuses and saffron is a plastidial enzyme. New Phytol. 2016;209:650–663. doi: 10.1111/nph.13609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moraga AR, Nohales PF, Perez JA, Gomez-Gomez L. Glucosylation of the saffron apocarotenoid crocetin by a glucosyltransferase isolated from Crocus sativus stigmas. Planta. 2004;219:955–966. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu H, Song J, Luo H, Zhang Y, Li Q, Zhu Y, Xu J, Li Y, Song C, Wang B, et al. Analysis of the genome sequence of the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza. Mol Plant. 2016;9:949–952. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu J, Chu Y, Liao B, Xiao S, Yin Q, Bai R, Su H, Dong L, Li X, Qian J, et al. Panax ginseng genome examination for ginsenoside biosynthesis. Gigascience. 2017;6:1–15. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen W, Kui L, Zhang G, Zhu S, Zhang J, Wang X, Yang M, Huang H, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and analysis of the Chinese herbal plant Panax notoginseng. Mol Plant. 2017;10:899–902. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang D, Li W, Xia EH, Zhang QJ, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Tong Y, Zhao Y, Niu YC, Xu JH, Gao LZ. The medicinal herb Panax notoginseng genome provides insights into ginsenoside biosynthesis and genome evolution. Mol Plant. 2017;10:903–907. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mochida K, Sakurai T, Seki H, Yoshida T, Takahagi K, Sawai S, Uchiyama H, Muranaka T, Saito K. Draft genome assembly and annotation of Glycyrrhiza uralensis, a medicinal legume. Plant J. 2017;89:181–194. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt MH, Vogel A, Denton AK, Istace B, Wormit A, van de Geest H, Bolger ME, Alseekh S, Mass J, Pfaff C, et al. De novo assembly of a new Solanum pennellii accession using nanopore sequencing. Plant Cell. 2017;29:2336–2348. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burton JN, Adey A, Patwardhan RP, Qiu R, Kitzman JO, Shendure J. Chromosome-scale scaffolding of de novo genome assemblies based on chromatin interactions. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1119–1125. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X. Structure, mechanism and engineering of plant natural product glycosyltransferases. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3303–3309. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandi F, Bar E, Mourgues F, Horvath G, Turcsi E, Giuliano G, Liverani A, Tartarini S, Lewinsohn E, Rosati C. Study of ‘Redhaven’ peach and its white-fleshed mutant suggests a key role of CCD4 carotenoid dioxygenase in carotenoid and norisoprenoid volatile metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rendon-Anaya M, Ibarra-Laclette E, Mendez-Bravo A, Lan T, Zheng C, Carretero-Paulet L, Perez-Torres CA, Chacon-Lopez A, Hernandez-Guzman G, Chang TH, et al. The avocado genome informs deep angiosperm phylogeny, highlights introgressive hybridization, and reveals pathogen-influenced gene space adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:17081–17089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1822129116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukushima K, Fang X, Alvarez-Ponce D, Cai H, Carretero-Paulet L, Chen C, Chang TH, Farr KM, Fujita T, Hiwatashi Y, et al. Genome of the pitcher plant Cephalotus reveals genetic changes associated with carnivory. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1:59. doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27:722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H. Minimap and miniasm. Fast mapping and de novo assembly for noisy long sequences. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2103–2110. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Istace B, Friedrich A, d'Agata L, Faye S, Payen E, Beluche O, Caradec C, Davidas S, Cruaud C, Liti G, et al. De novo assembly and population genomic survey of natural yeast isolates with the Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencer. Gigascience. 2017;6:1–13. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giw018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, Cuomo CA, Zeng Q, Wortman J, Young SK, Earl AM. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:578–579. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roach MJ, Schmidt SA, Borneman AR. Purge Haplotigs: allelic contig reassignment for third-gen diploid genome assemblies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2018;19:460. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2485-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ou S, Jiang N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:1410–1422. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cantarel BL, Korf I, Robb SM, Parra G, Ross E, Moore B, Holt C, Sanchez Alvarado A, Yandell M. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 2008;18:188–196. doi: 10.1101/gr.6743907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nawrocki EP, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2933–2935. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Enright AJ, Van Dongen S, Ouzounis CA. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, Hahn MW. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lyons E, Pedersen B, Kane J, Alam M, Ming R, Tang H, Wang X, Bowers J, Paterson A, Lisch D, Freeling M. Finding and comparing syntenic regions among Arabidopsis and the outgroups papaya, poplar, and grape: CoGe with rosids. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1772–1781. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.124867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lyons E, Pedersen B, Kane J, Freeling M. The value of nonmodel genomes and an example using SynMap within CoGe to dissect the hexaploidy that predates the rosids. Trop Plant Biol. 2008;1:181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ibarra-Laclette E, Lyons E, Hernandez-Guzman G, Perez-Torres CA, Carretero-Paulet L, Chang TH, Lan T, Welch AJ, Juarez MJ, Simpson J, et al. Architecture and evolution of a minute plant genome. Nature. 2013;498:94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mirarab S, Nguyen N, Guo S, Wang LS, Kim J, Warnow T. PASTA: ultra-large multiple sequence alignment for nucleotide and amino-acid sequences. J Comput Biol. 2015;22:377–386. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2014.0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2--approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu Z, Pu X, Gao R, Demurtas OC, Fleck SJ, Richter M, He C, Ji A, Sun W, Kong J, et al. Supplementary Datasets. 2020. NCBI BioProject accession: PRJNA477438. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA477438].

- 67.Xu Z, Pu X, Gao R, Demurtas OC, Fleck SJ, Richter M, He C, Ji A, Sun W, Kong J, et al. Supplementary Datasets. 2020. Whole Genome Shotgun project: VZDL00000000. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/VZDL00000000].

- 68.Xu Z, Pu X, Gao R, Demurtas OC, Fleck SJ, Richter M, He C, Ji A, Sun W, Kong J, et al. Supplementary Datasets. 2019. CoGe genome ID: id53980. [https://genomevolution.org/coge/SearchResults.pl?s=Gardenia&p=genome].

- 69.Xu Z, Pu X, Gao R, Demurtas OC, Fleck SJ, Richter M, He C, Ji A, Sun W, Kong J, et al. Supplementary Datasets. 2019. CoGe genome ID: id55476. [https://genomevolution.org/coge/SearchResults.pl?s=Gardenia&p=genome].

- 70.Xu Z, Pu X, Gao R, Demurtas OC, Fleck SJ, Richter M, He C, Ji A, Sun W, Kong J, et al. Supplementary Datasets. 2019. CoGe genome ID: id55477. [https://genomevolution.org/coge/SearchResults.pl?s=Gardenia&p=genome].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Detailed methods and results for genome sequencing.

Additional file 2: Figures S1-S26; Tables S1-S18.

Additional file 3. Detailed methods and results for crocin biosynthesis.

Additional file 4: Figure S27. Pasta phylogenetic tree of NMTs from different species.

Additional file 5: Figure S28. Pasta phylogenetic tree of CCDs from different species.

Additional file 6: Figure S29. Pasta phylogenetic tree of UGTs from different species.

Additional file 7: Figure S30. Pasta phylogenetic tree of ALDHs from different species.

Data Availability Statement

G. jasminoides line 1–9 and the constructs used in this work can be obtained by writing to K.H. (email: 402632144@qq.com). Genome sequence and assembly data were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive from the NCBI under the accession number PRJNA477438 [66]. The assembled genomes including nuclear genome, chloroplast genome, and mitochondrial genome for G. jasminoides were submitted to the NCBI genome resource with accession no. VZDL00000000 [67], and the CoGe with id53980 [68], id55476 [69], and id55477 [70], respectively.