Abstract

Findings from studies investigating associations of residential environment with poor birth outcomes have been inconsistent. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, we examined associations of neighborhood disadvantage with preterm birth (PTB) and low birthweight (LBW), and explored differences in relationships among racial groups. Two reviewers searched English language articles in electronic databases of published literature. We used random effects logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) relating neighborhood disadvantage with PTB and LBW. Neighborhood disadvantage, most disadvantaged versus least disadvantaged neighborhoods, was defined by researchers of included studies, and comprised of poverty, deprivation, racial residential segregation or racial composition, and crime. We identified 1,314 citations in the systematic review. The meta-analyses included 7 PTB and 14 LBW cross-sectional studies conducted in the United States (U.S.). Overall, we found 27% [95%CI: 1.16, 1.39] and 11% [95%CI: 1.07, 1.14] higher risk for PTB and LBW among the most disadvantaged compared with least disadvantaged neighborhoods. No statistically significant association was found in meta-analyses of studies that adjusted for race. In race-stratified meta-analyses models, we found 48% [95%CI: 1.25, 1.75] and 61% [95%CI: 1.30, 2.00] higher odds of PTB and LBW among non-Hispanic white mothers living in most disadvantaged neighborhoods compared with those living in least disadvantaged neighborhoods. Similar, but less strong, associations were observed for PTB (15% [95%CI: 1.09, 1.21]) and LBW (17% [95%CI: 1.10, 1.25]) among non-Hispanic black mothers. Neighborhood disadvantage is associated with PTB and LBW, however, associations may differ by race. Future studies evaluating causal mechanisms underlying the associations, and racial/ethnic differences in associations, are warranted.

Keywords: USA, Neighborhood, Perinatal epidemiology, Birth weight, Preterm birth, Social epidemiology, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) and low birthweight (LBW) place an infant at increased risk of morbidity and mortality from neurological, pulmonary and ophthalmic disorders (WHO, 2002). They also increase risk for poor health over the life course, including risk for chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease (Martin, Hamilton, Ventura, Osterman, & Mathews, 2013) and type II diabetes mellitus (Martin et al., 2013), costing the nation billions of dollars in health care expenditures and lost earnings potential due to premature death or morbidity. Several risk factors including maternal biological characteristics (e.g. age at delivery) and behaviors (e.g. tobacco and alcohol consumption) have been identified for LBW (David & Collins, 1997; Mumbare et al., 2012) and PTB (Stewart & Graham, 2010; Tepper et al., 2012). Further, disparities in risk for PTB or LBW among racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups have been well documented. Researchers have looked beyond individual characteristics for factors that may explain risk for LBW and PTB as well as observed disparities (Alio et al., 2010; Wells, 2010). Previous findings from studies examining residential environment, the neighborhood in which mothers lived before or during pregnancy, in relation to LBW and PTB have been inconsistent. Most, although not all (Cubbin et al., 2008), researchers have reported that neighborhood disadvantage increases the risk for poor birth outcomes even after adjusting for maternal covariates (Auger, Giraud, & Daniel, 2009; J. W. Collins Jr, David, Rankin, & Desireddi, 2009; Janevic et al., 2010; Luo, Wilkins, & Kramer, 2006; Schempf, Strobino, & O'Campo, 2009).

Living in a more disadvantaged economic and social environment can lead to relative deprivation, increased exposure to crime, decreased access to nutritious foods, increased risk of intimate partner abuse, strain from economic instability, and stunted economic growth and social mobility opportunities, all of which can contribute to maternal stress. Maternal stress can lead to higher levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone and cortisol which could trigger contractions and/or the premature rupture of the membrane resulting in PTB (Hodgson & Lockwood, 2010). Maternal stress also leads to the release of catecholamines, such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine, into the blood which can cause placental hypoperfusion, a consequence of which is constraint of nutrients and oxygen to the fetus(Rondo et al., 2003) resulting in intrauterine growth retardation and LBW (Wu, Bazer, Cudd, Meininger, & Spencer, 2004).

Besides the inconsistency of previous studies, to our knowledge, there are only two published meta-analyses on the association of neighborhood deprivation with PTB (Vos, Posthumus, Bonsel, Steegers, & Denktas, 2014) and LBW (Metcalfe, Lail, Ghali, & Sauve, 2011), and neither examined how these associations differ among racial subgroups. In the United States (U.S.), despite decline in racial residential segregation over the last few decades, blacks are still disproportionately represented in areas of higher social and economic disadvantage (J. W. Collins Jr, Herman, & David, 1997; Ellen, 2008; Iceland, Weinberg, & Steinmetz, 2002; P. O'Campo, Xue, Wang, & Coughy, 1997; Pickett, Ahern, Selvin, & Abrams, 2002). With different social histories, we assumed it possible that the association between neighborhood disadvantage and birth outcomes could differ between these groups. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association of neighborhood disadvantage with PTB and LBW to synthesize the results of individual studies in the published literature, analyze differences in the results of these studies, and examine potential differences among racial groups (Walker, Hernandez, & Kattan, 2008).

Methods

Overview

This systematic review and meta-analysis was based on observational studies conducted in the U.S. using objective measures of primary or secondary data, among native- and foreign-born women, who delivered a live-born infant in the U.S. Data from studies that were conducted among non-Hispanic (NH) white and NH black mothers were used in the current study.

Search strategy and study selection

This study was performed using guidelines established by the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) (Stroup et al., 2000) and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statements (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009). Authors CN and AH searched the electronic databases using established search terms and reviewed titles and abstracts of citations against inclusion/exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies in inclusion were resolved via discussion. Full-text articles corresponding to these citations were identified and read by the primary reviewer (CN), and manual searches of these articles’ bibliographies were performed. Articles were managed using EndNote X7.1 software.

The following search terms were entered in PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and ProQuest Dissertation and Theses Full Text electronic databases: (premature birth/preterm birth or low birthweight) and (neighborhood or residence area/characteristics). A detailed search strategy for each database was designed in consultation with a Public Health Informationist (Supplementary File 1). The following studies were excluded: 1) studies that only described prevalence/incidence of LBW or PTB, without analysis of associations of neighborhood measures with these outcomes, 2) studies that described measurement of neighborhood context without analyses of its relationship with risk for PTB or LBW, 3) studies comparing various geographic scales of measurement, without the analysis of the neighborhood measure on the outcomes, 4) studies that used city, Metropolitan Statistical Area, county, or larger, as the geographic unit, and 5) studies where the only neighborhood variable used was a measure of pollution (e.g. noise pollution from freeways).

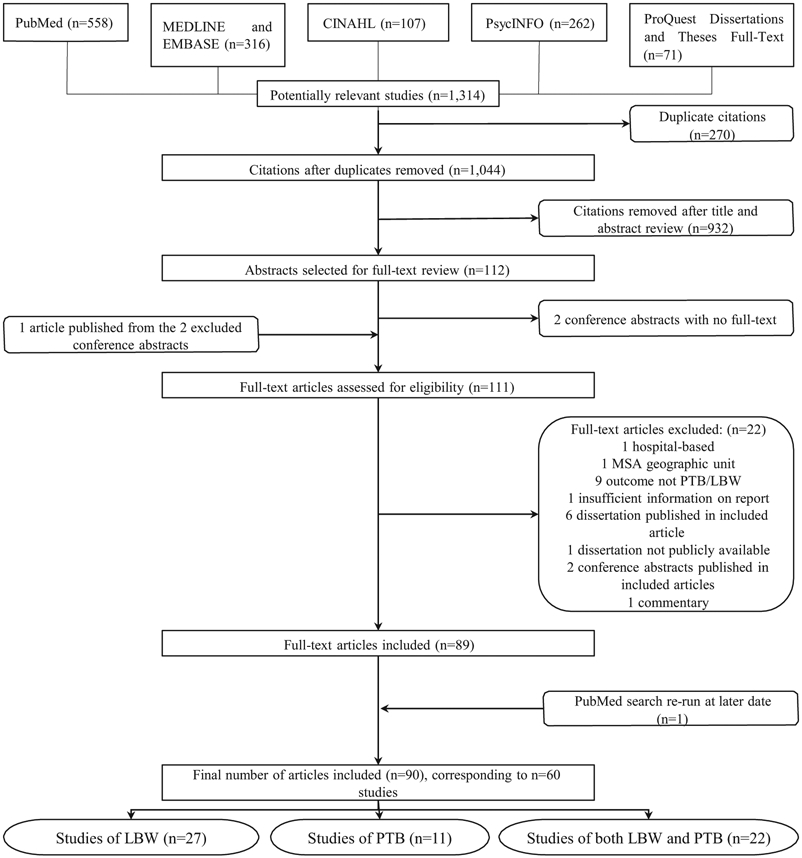

The initial search date of the databases was March 20, 2014. We re-ran the PubMed search on August 26, 2014. The search strategy produced a total of 1,314 citations on March 20, 2014. All studies published in the English Language were considered with no limitation by publication date. From these citations, 270 duplicates were removed, leaving 1,044 for title and abstract review. After application of exclusion criteria, full-text article review, a re-run of the PubMed search, and manual bibliography review, a total of 90 publications (Anthopolos, James, Gelfand, & Miranda, 2011; Anthopolos, Kaufman, Messer, & Miranda, 2014; Baker & Hellerstedt, 2006; Bloch, 2011; Brewin, 2007; Chu, 2010; J. Collins Jr, K. Rankin, & R. David, 2011; J. Collins Jr, Rankin, & Hedstrom, 2012; J. Collins Jr, Rankin, & Janowiak, 2013; J. W. Collins Jr & David, 1990, 1997; J. W. Collins Jr, David, et al., 2009; J. W. Collins Jr, David, Simon, & Prachand, 2007; J. W. Collins Jr et al., 1997; J. W. Collins Jr, K. M. Rankin, & R. J. David, 2011; J. W. Collins Jr, Schulte, & Drolet, 1998; J. W. Collins Jr & Shay, 1994; J. W. Collins Jr, Wambach, David, & Rankin, 2009; Cubbin et al., 2008; Debbink & Bader, 2011; Devine, 2009; Doebler, 2011; Dooley, 2010; English et al., 2003; Fang, Madhavan, & Alderman, 1999; Finch, Lim, Perez, & Do, 2007; Gould & LeRoy, 1988; Grady, 2006, 2010; Grady & McLafferty, 2007; Grady & Ramírez, 2008; Gray, Edwards, Schultz, & Miranda, 2014; Henry Akintobi, 2006; Hillemeier, Weisman, Chase, & Dyer, 2007; Holzman et al., 2009; Howell, Pettit, & Kingsley, 2005; Huynh & Maroko, 2014; Jaffee & Perloff, 2003; Janevic et al., 2010; M. A. Johnson & Marchi, 2009; T. Johnson, Drisko, Gallagher, & Barela, 1999; Kent, McClure, Zaitchik, & Gohlke, 2013; M. Kramer, Dunlop, & Hogue, 2014; Kruger, Munsell, & French-Turner, 2011; Love, David, Rankin, & Collins Jr, 2010; Ma, 2013; Madkour, Harville, & Xie, 2014; Mair & Gruenewald, 2011; Masi, Hawkley, Piotrowski, & Pickett, 2007; Mason et al., 2011a, 2011b; Mason, Kaufman, Emch, Hogan, & Savitz, 2010; Mason, Messer, Laraia, & Mendola, 2009; Mendez, Hogan, & Culhane, 2011; Messer, Kaufman, Dole, Herring, & Laraia, 2006; Messer, Kaufman, Dole, Savitz, & Laraia, 2006; Messer, Kaufman, Mendola, & Laraia, 2008; Messer, Oakes, & Mason, 2010; Messer, Vinikoor, et al., 2008; Messina & Kramer, 2013; Miranda, Messer, & Kroeger, 2012; Morenoff, 2003; Nkansah-Amankra, 2010; Nkansah-Amankra, Dhawain, Hussey, & Luchok, 2010; Nkansah-Amankra, Luchok, Hussey, Watkins, & Liu, 2010; P. O'Campo et al., 2008; Patricia O'Campo, Caughy, Aronson, & Xue, 1997; P. O'Campo et al., 1997; Pardo-Crespo et al., 2013; Phillips, Wise, Rich-Edwards, Stampfer, & Rosenberg, 2009, 2013; Pickett, Collins, Masi, & Wilkinson, 2005; Ponce, Hoggatt, Wilhelm, & Ritz, 2005; Rauh, Andrews, & Garfinkel, 2001; Reagan & Salsberry, 2005; Reed, 2012; Rich-Edwards, Buka, Brennan, & Earls, 2003; Richard, 2006; Roberts, 1997; Schempf, Kaufman, Messer, & Mendola, 2011; Sims & Rainge, 2002; Sims, Sims, & Bruce, 2007; Sims, Sims, & Bruce, 2008; South et al., 2012; Strutz, Dozier, van Wijngaarden, & Glantz, 2012; Subramanian, Chen, Rehkopf, Waterman, & Krieger, 2006; Vinikoor-Imler, Messer, Evenson, & Laraia, 2011; Vinikoor, Kaufman, MacLehose, & Laraia, 2008; D. Wallace, 2011; M. Wallace et al., 2013), corresponding to 60 studies, were included in the systematic review and eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. These studies were population-based, cohort, longitudinal, and cross-sectional studies. We did not identify any published case-control study. When multiple articles were published from the same dataset, the article with the most data pertinent to the analysis of interest was selected. See Figure 1 for the flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic literature review study selection

Data collection

The primary reviewer (CN) used data extraction sheets to collect study characteristics and odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from each article. ORs of neighborhood-PTB/LBW associations were extracted from studies reporting the fully adjusted models as well as race-stratified models, if available. This information was managed in Microsoft Excel 2013 and provided data to perform the meta-analyses. Attempts were made to contact authors of selected articles for information pertinent to the meta-analyses but not included in the published articles.

Exposure and Outcome Definitions

The operationalization of the independent variable, neighborhood disadvantage, differed among the studies reviewed and was defined by the researchers of the included studies. The neighborhood predictors used in the studies varied: poverty, deprivation, racial residential segregation or racial composition, and crime. Poverty was operationalized as either median household income or the percentage of the neighborhood population living below the poverty level. Deprivation was customarily measured via the compilation of multiple neighborhood characteristics such as employment, income/poverty, education, housing, occupations, and crime. Some studies have also used racial composition, as a measure of segregation (Baker & Hellerstedt, 2006; Mason et al., 2009; Messer et al., 2010) or separately from segregation (Reichman, Teitler, & Hamilton, 2009), though the rationale for its use was not typically stated. Mothers were considered ‘exposed’ if they lived in the most, relative to least, disadvantaged neighborhoods before or during pregnancy. PTB and LBW were the outcome variables. PTB is the birth of an infant prior to 37 completed weeks of gestation, while an infant is considered to have LBW if it weighs less than 2,500 grams at birth (Iams & Romero, 2007).

Statistical analysis

The objective of this meta-analysis was to calculate the odds of PTB and LBW related to living in disadvantaged neighborhoods, and explore any differences among racial groups. Overall, 27, 11, and 22 of the 60 identified studies had LBW, PTB, and both PTB and LBW as their primary outcome(s), respectively. Therefore, we assessed 33 studies for PTB and 49 studies for LBW. Seven of the 33 PTB studies reported an adjusted OR of the association with neighborhood disadvantage that compared those living in the most, relative to least, disadvantaged areas and contributed to the summary OR describing association of PTB with neighborhood disadvantage. Three of the seven studies controlled for race; the four remaining studies had sufficient data to perform analyses for NH white mothers, and three of these studies sufficient data for NH black mothers. One study included eight cities/counties, with research at each site conducted by independent researchers and these data were analyzed as independent studies, resulting in 11 ORs for NH white mothers and 10 ORs for NH black mothers. Fourteen of the 49 LBW studies contributed to the summary OR describing association of LBW with neighborhood disadvantage. Eight of the 14 studies controlled for race; of the remaining studies, five had sufficient data to perform analyses among NH white and five among NH black women. One study included data from five counties, which were included separately, resulting in nine ORs each for analyses among NH whites and NH blacks.

Summary ORs were calculated using DerSimonian and Laird (DerSimonian & Laird, 1986) (random effects) models which incorporate inter-study variation in estimating the summary measure. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 and Cochran’s Q test statistic. I2: 0% for no observed variability and 100% for high variability. I2 is used to assess the inconsistency of effect sizes among the studies reviewed, i.e. the proportion of the total variance that is true, while Cochran’s Q P-values were used to measure statistical significance of heterogeneity (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009; Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, 2003). The summary OR, along with 95% CI, was the principal summary measure. Publication bias was examined using the Egger’s regression asymmetry test (Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider, & Minder, 1997) and Begg’s adjusted rank correlation test (Begg & Mazumdar, 1994). Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 13.1, software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Results

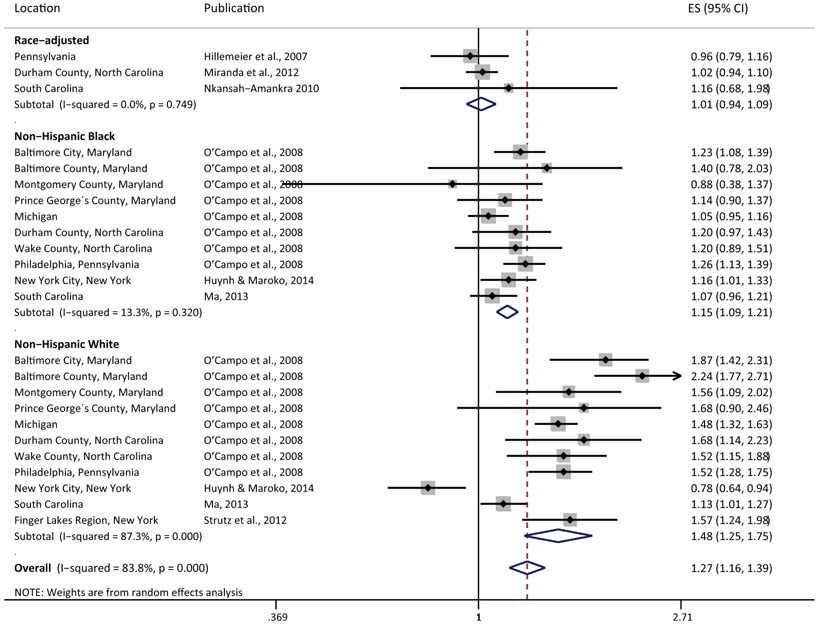

Information on the characteristics of each study described in the articles (e.g. location, sample size, population, inclusion/exclusion criteria) was abstracted (Supplementary File 2). For the majority (53%) of articles, the census tract was the geographical unit of analysis at the neighborhood level. Overall, those living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods had a 27% higher risk for PTB compared with those living in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods (OR: 1.27 [95% CI: 1.16, 1.39]); there was high variability among these studies (I2 = 83.8%, P<0.001) and the heterogeneity was statistically significant. This association was not evident among studies adjusting for race (OR: 1.01 [95% CI: 0.94, 1.09]), where there was no observed heterogeneity among the studies’ effect sizes (I2 = 0.0%, P=0.749). Among NH whites, women living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods had 48% higher risk of PTB compared with women living in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods (OR: 1.48 [95% CI: 1.25, 1.75]); variability among the studies was high (I2 = 87.3%, P<0.001) and heterogeneity statistically significant. Among NH blacks, women living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods had 15% higher risk of PTB compared with women living in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods (OR: 1.15 [95% CI: 1.09, 1.21]); heterogeneity was not statistically significant and variability among these studies was low (I2 = 13.3%, P=0.320) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Odds ratios and confidence intervals of associations between neighborhood disadvantage and preterm birth among race-adjusted and race-stratified models. Summary odds ratios and 95% confidence interval calculated using random effects models

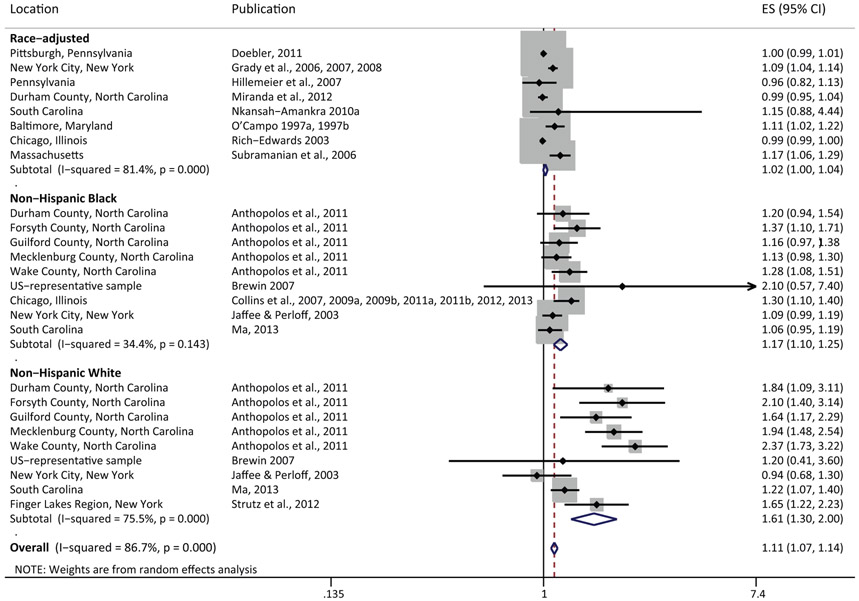

Overall, those living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods had an 11% higher risk for LBW compared with those living in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods (OR: 1.11 [95% CI: 1.07, 1.14]); there was high variability and statistically significant heterogeneity among these studies (I2 = 86.7%, P<0.001). The association between neighborhood disadvantage and LBW was not evident in studies adjusting for race (OR: 1.02 [95% CI: 1.00, 1.04]); however, there was high variability and significant heterogeneity among these studies (I2 = 81.4%, P<0.001). Among NH whites, women living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods had 61% higher risk of LBW compared with women living in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods (OR: 1.61 [95% CI: 1.30, 2.00]). Among NH blacks, women living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods had 17% higher risk of LBW compared with women living in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods (OR: 1.17 [95% CI: 1.10, 1.25]). The variability among the NH white studies was moderate and heterogeneity statistically significant (I2 = 75.5%, P<0.001), while the heterogeneity was not statistically significant, and variability was low, among the NH black studies (I2 = 34.4%, P=0.143) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Odds ratios and confidence intervals of associations between neighborhood disadvantage and low birth weight among race-adjusted and race-stratified models. Summary odds ratios and 95% confidence interval calculated using random effects models

Findings of Egger’s regression asymmetry tests for the meta-analyses performed on the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and PTB for race-adjusted models (P=0.920), NH white models (P=0.805), and NH black models (P=0.354) were not significant. Similar tests for the meta-analyses performed on the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and LBW for race-adjusted models (P=0.071), NH white models (P=0.114), and NH black models (P=0.227) were also not significant. Begg’s adjusted rank correlation tests were also statistically non-significant (P>0.05).

Discussion

Overall, we found that mothers living in the most disadvantaged, relative to the least disadvantaged, neighborhoods had a 27% higher risk for PTB and 11% higher risk for LBW. Both NH whites and NH blacks were at higher risk for these poor birth outcomes if they lived in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods, albeit the odds ratios were of smaller magnitude among NH blacks. NH white mothers in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods were 48% and 61% more likely to have PTB and LBW infants, respectively, compared with NH white mothers resident in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods. NH black mothers in the most disadvantaged areas were 15% and 17% more likely to have PTB and LBW infants, relative to their counterparts in the least disadvantaged areas.

Notably, we found no association between birth outcomes and neighborhood disadvantage in meta-analyses of studies that adjusted for race. This could be explained by the fact that including race in the model captures aspects of the neighborhood environment that either explain the associations or are closely related to the factors that explain the associations. This is not too surprising as race is a well-documented predictor of where people live in the U.S. (Ellen, Cutler, & Dickens, 2000; Iceland et al., 2002).

A potential explanation for the difference among racial groups in the association between neighborhood disadvantage and PTB/LBW may be that there are unmeasured factors among NH blacks, irrespective of neighborhood context, that increase risk for poor birth outcomes thus minimizing differences observed between groups in the advantaged/disadvantaged neighborhoods. For example, baseline rates of PTB and LBW are 1.5 and 2 times higher, respectively, among NH black mothers, relative to NH whites (Hamilton, Martin, Osterman, & Curtin, 2014). Among NH whites there was moderate to high variability, and statistically significant heterogeneity, among the studies, while for NH blacks heterogeneity was non-significant, and variability low, suggesting relatively consistent estimates of the association of neighborhood disadvantage with PTB and LBW for NH blacks. Studies examining the association between individual-level risk factors and poor birth outcomes have similarly found differences by race in the magnitude of the association (Ahern, Pickett, Selvin, & Abrams, 2003; J. W. Collins Jr & David, 1990; Masi et al., 2007). We could not assess effect modification by race because the studies included in the meta-analyses for NH whites were already heterogeneous.

Findings from previous work and our meta-analysis provide a basis for more work to be done to understand the causal mechanisms at play. To do so, theoretical frameworks describing aspects of neighborhoods potentially related to birth outcomes are needed as they will inform the selection of relevant measures and statistical models. Research into neighborhood effects is relatively new. As a result these theoretical bases and mechanisms are still underdeveloped. Theoretically-founded measures at the biological-, behavioral-, familial-, and neighborhood-levels (M. R. Kramer, Cooper, Drews-Botsch, Waller, & Hogue, 2010; Roberts, 1997; Schempf et al., 2011) will allow for more rigorous and comprehensive study of the complexities likely involved in the relationship between neighborhood context and birth outcomes. The use of spatial measures of neighborhood variables may also be of great benefit to this area of research (Mason et al., 2009) as it cannot be assumed that health is affected only within the lines that make up a census block group or census tract. We have been limited in our ability to study the role of neighborhood context on PTB subtypes because only a minority of articles make a distinction in whether the birth was medically indicated/iatrogenic or spontaneous. The literature is suggestive of a stronger relationship between neighborhood context and spontaneous PTB, but not medically indicated PTB (Phillips et al., 2009), but more research is needed.

Limitations

The number of studies included in the meta-analyses was small relative to the number identified in the systematic literature review; as a result there is a potential for selection bias. The majority of studies included in the current systematic review and meta-analysis were cross-sectional in nature, thus limiting the ability to distinguish temporal relationships underlying the association of neighborhood context with PTB and LBW; however, this is a limitation of the studies currently published in this field rather than our study design. As a meta-analysis of observational studies, this study faced the inherent challenge of summarizing the results of studies with differing study designs (Stroup et al., 2000). Differences found between neighborhood disadvantage groupings cannot be attributed solely to that grouping criteria as they may be the result of unmeasured factors associated with definition of the groupings (Borenstein et al., 2009). For studies that included multiple neighborhood predictors, we arbitrarily selected one, usually the more commonly used measure in order to improve comparability with other studies. The definition of neighborhood disadvantage was not predetermined; although this provides a more comprehensive overview of the operationalization of neighborhood disadvantage in this field, it also has the limitation of potentially comparing different constructs. The authors intended to perform meta-regression to examine the extent to which heterogeneity among the studies was a result of the following study-level characteristics: the operationalization of the neighborhood context variable; the scale of the neighborhood variable, i.e. continuous, dichotomous, tertiles, quartiles, or quintiles; the geographic unit used to define the neighborhood; whether or not multilevel modeling was used; and, whether the data was published in a journal article or part of grey literature. However, due to fewer than 10 studies per covariate (Borenstein et al., 2009) these results were not reported. Most studies in this meta-analysis used data from the eastern U.S. The manner in which the history and politics of the country have determined differences in demographics, and social and economic neighborhood environments and other characteristics could limit the generalizability of these findings.

Publication bias is a limitation of systematic reviews and meta-analyses because studies with statistically significant findings and higher effect sizes are more likely to be reported in published literature and thus included in a meta-analysis. To mitigate this concern, we included unpublished theses and dissertations. We also tested the potential for publication bias using Egger’s regression asymmetry and Begg’s adjusted rank correlation tests. Overall, the tests did not suggest the presence of this bias. Duplication bias is present when studies with statistically significant findings and higher effect sizes are more likely to lead to multiple publications and presentations (Borenstein et al., 2009; Tramer, Reynolds, Moore, & McQuay, 1997) and, therefore, more likely to be selected for inclusion in meta-analysis. It is not always clear when publications come from the same study, however, efforts were made to eliminate duplicates by reviewing author names, geographic location of birth records and years of birth data, as well as contacting researchers when determination of multiple publications could not be made with certainty.

We used Stata software, version 13.1, to employ the DerSimonian and Laird procedure for random effects meta-analysis, which is accurate for a large number of studies (>20). However, the accuracy of the test varies with the heterogeneity (I2) value (Jackson, Bowden, & Baker, 2010). When there are a small number of studies in a meta-analysis, heterogeneity estimates using the DerSimonian and Laird procedure (random effects) may not be accurate and using fixed effects models is recommended (Borenstein et al., 2009). As a sensitivity analysis, we replicated the PTB model which included three studies that adjusted for race and performed both fixed and random effects models. We obtained the same results, suggesting that there was insufficient information to calculate the I2 heterogeneity measure. However, using the DerSimonian and Laird procedure the actual coverage probability of a nominal 95% CI with four studies and low heterogeneity is still close to 95% and so the small number of studies may not be of huge concern in this case.

Conclusion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that overall, neighborhood disadvantage is associated with PTB and LBW in race-stratified, but not race-adjusted, models. Furthermore, we found that associations among NH whites were much stronger than associations among NH blacks.

Supplementary Material

Research highlights.

Mothers in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods have 27% higher risk for PTB

Mothers in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods have 11% higher risk for LBW

The association with neighborhood disadvantage is stronger among whites than blacks

Acknowledgements

We would like to Barbara Folb, Public Health Informationist at the University Of Pittsburgh Graduate School Of Public Health, for assisting with the search strategy design, and Brian McGill, doctoral student in the University Of Pittsburgh Department Of Statistics, for reviewing the meta-analysis methodology. Dr. Ncube was supported by the Reproductive, Perinatal and Pediatric Epidemiology Training Program of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32 HD052462).

Footnotes

Statement of no Ethics Approval Required

The data used in this systematic review and meta-analysis were extracted from published literature available through electronic academic databases. No human subjects ethics approval was required for this study.

References

- Ahern J, Pickett KE, Selvin S, & Abrams B (2003). Preterm birth among African American and white women: a multilevel analysis of socioeconomic characteristics and cigarette smoking. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67, 606–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alio AP, Richman AR, Clayton HB, Jeffers DF, Wathington DJ, & Salihu HM (2010). An ecological approach to understanding black-white disparities in perinatal mortality. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(4), 557–566. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0495-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthopolos R, James SA, Gelfand AE, & Miranda ML (2011). A spatial measure of neighborhood level racial isolation applied to low birthweight, preterm birth, and birthweight in North Carolina. Spatial and Spatio-temporal Epidemiology, 2(4), 235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthopolos R, Kaufman JS, Messer LC, & Miranda ML (2014). Racial residential segregation and preterm birth: built environment as a mediator. Epidemiology, 25(3), 397–405. doi: 10.1097/ede.0000000000000079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger N, Giraud J, & Daniel M (2009). The joint influence of area income, income inequality, and immigrant density on adverse birth outcomes: a population-based study. BMC Public Health, 9, 237. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AN, & Hellerstedt WL (2006). Residential racial concentration and birth outcomes by nativity: do neighbors matter? Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(2), 172–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, & Mazumdar M (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics, 50(4), 1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch JR (2011). Using geographical information systems to explore disparities in preterm birth rates among foreign-born and U.S.-born Black mothers. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 40(5), 544–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01273.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, & Rothstein HR (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, U.K.: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin D (2007). Contributions of multidimensional contextual factors during adolescence and young adulthood to racial disparities in birth outcomes. (68 PhD Dissertation), University of Massachusetts; Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=psyc5&AN=2007-99200-466 [Google Scholar]

- http://linksource.ebsco.com/linking.aspx?sid=OVID:psycdb&id=pmid:&id=doi:&issn=0419-4217&isbn=&volume=68&issue=4-B&spage=2244&date=2007&title=Dissertation+Abstracts+International%3A+Section+B%3A+The+Sciences+and+Engineering&atitle=Contributions+of+multidimensional+contextual+factors+during+adolescence+and+young+adulthood+to+racial+disparities+in+birth+outcomes.&aulast=Brewin&pid=%3CAN%3E2007-99200-466%3C%2FAN%3E Available from Ovid Technologies PsycINFO database. (4-B) [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y-Y (2010). Maternal and infant health of immigrant in the capital tri-county area in Michigan. (1487217 thesis MS), Michigan State University, Ann Arbor, MI: Retrieved from http://pitt.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/815409963?accountid=14709 ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Full-text database. [Google Scholar]

- Collins J Jr, Rankin K, & David R (2011). Low Birth Weight Across Generations: The Effect of Economic Environment. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(4), 438–445. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0603-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J Jr, Rankin K, & Hedstrom A (2012). Exploring Weathering: the Relation of Age to Low Birth Weight Among First Generation and Established United States-Born Mexican-American Women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(5), 967–972. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0827-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J Jr, Rankin K, & Janowiak C (2013). Suburban Migration and the Birth Outcome of Chicago-Born White and African-American Women: The Merit of the Healthy Migrant Theory? Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17(9), 1559–1566. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1154-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, & David RJ (1990). The differential effect of traditional risk factors on infant birthweight among Blacks and Whites in Chicago. American Journal of Public Health, 80(6), 679–681. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.80.6.679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, & David RJ (1997). Urban violence and African-American pregnancy outcome: an ecologic study. Ethnicity and Disease, 7(3), 184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, David RJ, Rankin KM, & Desireddi JR (2009). Transgenerational effect of neighborhood poverty on low birth weight among African Americans in Cook County, Illinois. American Journal of Epidemiology, 169(6), 712–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, David RJ, Simon DM, & Prachand NG (2007). Preterm birth among African American and white women with a lifelong residence in high-income Chicago neighborhoods: an exploratory study. Ethnicity and Disease, 17(1), 113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, Herman AA, & David RJ (1997). Very-low-birthweight infants and income incongruity among African American and white parents in Chicago. American Journal of Public Health, 87(3), 414–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, Rankin KM, & David RJ (2011). African American women's lifetime upward economic mobility and preterm birth: the effect of fetal programming. American Journal of Public Health, 101(4), 714–719. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2010.195024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, Schulte NF, & Drolet A (1998). Differential effect of ecologic risk factors on the low birthweight components of African-American, Mexican-American, and non-Latino white infants in Chicago. Journal of the National Medical Association, 90(4), 223–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, & Shay DK (1994). Prevalence of low birth weight among Hispanic infants with United States-born and foreign-born mothers: the effect of urban poverty. American Journal of Epidemiology, 139(2), 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, Wambach J, David RJ, & Rankin KM (2009). Women's lifelong exposure to neighborhood poverty and low birth weight: A population-based study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13(3), 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubbin C, Marchi K, Lin M, Bell T, Marshall H, Miller C, et al. (2008). Is neighborhood deprivation independently associated with maternal and infant health? Evidence from Florida and Washington. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12(1), 61–74. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0225-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David RJ, & Collins JW Jr. (1997). Differing Birth Weight among Infants of U.S.-Born Blacks, African-Born Blacks, and U.S.-Born Whites. The New England Journal of Medicine, 337, 1209–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debbink MP, & Bader MD (2011). Racial residential segregation and low birth weight in Michigan's metropolitan areas. American Journal of Public Health, 101(9), 1714–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, & Laird N (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials, 7(3), 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine SJ (2009). Is there an epidemiological paradox for birth outcomes among Colorado women of Mexican origin? si y no: It depends on the outcome. (70 PhD dissertation), University of Colorado at Denver, Denver, CO: Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=psyc6&AN=2009-99220-368 [Google Scholar]

- http://linksource.ebsco.com/linking.aspx?sid=OVID:psycdb&id=pmid:&id=doi:&issn=0419-4217&isbn=9781109188646&volume=70&issue=5-B&spage=2872&date=2009&title=Dissertation+Abstracts+International%3A+Section+B%3A+The+Sciences+and+Engineering&atitle=Is+there+an+epidemiological+paradox+for+birth+outcomes+among+Colorado+women+of+Mexican+origin%3F+si+y+no%3A+It+depends+on+the+outcome.&aulast=Devine&pid=%3CAN%3E2009-99220-368%3C%2FAN%3E Available from Ovid Technologies PsycINFO database. (5-B) [Google Scholar]

- Doebler DCA (2011). Understanding racial disparities in low birth weight in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The role of area-level socioeconomic position and individual-level factors. (71 DrPH dissertation), University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=psyc7&AN=2011-99040-262 [Google Scholar]

- http://linksource.ebsco.com/linking.aspx?sid=OVID:psycdb&id=pmid:&id=doi:&issn=0419-4217&isbn=9781124145983&volume=71&issue=8-B&spage=4796&date=2011&title=Dissertation+Abstracts+International%3A+Section+B%3A+The+Sciences+and+Engineering&atitle=Understanding+racial+disparities+in+low+birth+weight+in+Pittsburgh%2C+Pennsylvania%3A+The+role+of+area-level+socioeconomic+position+and+individual-level+factors.&aulast=Doebler&pid=%3CAN%3E2011-99040-262%3C%2FAN%3E Available from Ovid Technologies PsycINFO database. (8-B) [Google Scholar]

- Dooley PA (2010). Examining individual and neighborhood-level risk factors for delivering a preterm infant. (70 PhD Dissertation), University of Cincinnati; Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=psyc6&AN=2010-99030-009 [Google Scholar]

- http://linksource.ebsco.com/linking.aspx?sid=OVID:psycdb&id=pmid:&id=doi:&issn=0419-4209&isbn=9781109303650&volume=70&issue=8-A&spage=3198&date=2010&title=Dissertation+Abstracts+International+Section+A%3A+Humanities+and+Social+Sciences&atitle=Examining+individual+and+neighborhood-level+risk+factors+for+delivering+a+preterm+infant.&aulast=Dooley&pid=%3CAN%3E2010-99030-009%3C%2FAN%3E Available from Ovid Technologies PsycINFO database. (8-A) [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, & Minder C (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. The BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen IG (2008). Continuing isolation: Segregation in America today In Carr JH & Kutty NK (Eds.), Segregation: The Rising Costs for America (Vol. 1). New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen IG, Cutler DM, & Dickens W (2000). Is Segregation Bad for Your Health? The Case of Low Birth Weight. Brookings-Wharton Papers on Urban Affairs, 203–238. [Google Scholar]

- English PB, Kharrazi M, Davies S, Scalf R, Waller L, & Neutra R (2003). Changes in spatial pattern of low birth weight in a southern California county: the role of individual and neighborhood level factors. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 2073–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Madhavan S, & Alderman MH (1999). Low Birth Weight: Race and Maternal Nativity - Impact of Community Income. Pediatrics, 103(1), e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Lim N, Perez W, & Do D (2007). Toward a population health model of segmented assimilation: The case of low birth weight in Los Angeles. Sociological Perspectives, 50(3), 445–468. [Google Scholar]

- Gould JB, & LeRoy S (1988). Socioeconomic status and low birth weight: a racial comparison. Pediatrics, 82(6), 896–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SC (2006). Racial disparities in low birthweight and the contribution of residential segregation: a multilevel analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 63(12), 3013–3029. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SC (2010). Racial residential segregation impacts on low birth weight using improved neighborhood boundary definitions. Spatial and Spatio-temporal Epidemiology, 1(4), 239–249. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2010.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SC, & McLafferty S (2007). Segregation, nativity, and health: Reproductive health inequalities for immigrant and native-born black women in New York City. Urban Geography, 28(4), 377–397. [Google Scholar]

- Grady SC, & Ramírez IJ (2008). Mediating medical risk factors in the residential segregation and low birthweight relationship by race in New York City. Health & Place, 14(4), 661–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray SC, Edwards SE, Schultz BD, & Miranda ML (2014). Assessing the impact of race, social factors and air pollution on birth outcomes: a population-based study. Environmental Health, 13(1), 4. doi: 10.1186/1476-069x-13-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJ, & Curtin SC (2014). Births: Preliminary Data for 2013. Retrieved from Hyattsville, MD: [Google Scholar]

- Henry Akintobi T (2006). Analysis of the role of residential segregation on perinatal outcomes in Florida, Georgia and Louisiana. (3240382 PhD Dissertation), University of South Florida, Ann Arbor, MI: Retrieved from http://pitt.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/305263487?accountid=14709 ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Full-text database. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, & Altman DG (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. The BMJ, 327(7414), 557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillemeier MM, Weisman CS, Chase GA, & Dyer A-M (2007). Individual and community predictors of preterm birth and low birthweight along the rural-urban continuum in central Pennsylvania. The Journal of Rural Health, 23(1), 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson EJ, & Lockwood CJ (2010). Preterm Birth: A Complex Disease In Berghella V (Ed.), Preterm Birth: Prevention and Management. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Holzman C, Eyster J, Kleyn M, Messer LC, Kaufman JS, Laraia BA, et al. (2009). Maternal weathering and risk of preterm delivery. American Journal of Public Health, 99(10), 1864–1871. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2008.151589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EM, Pettit KLS, & Kingsley GT (2005). Trends in maternal and infant health in poor urban neighborhoods: Good news from the 1990s, but challenges remain. Public Health Reports, 120(4), 409–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh M, & Maroko AR (2014). Gentrification and preterm birth in New York City, 2008-2010. Journal of Urban Health, 91(1), 211–220. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9823-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iams JD, & Romero R (2007). Preterm Birth. In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, & Simpson JL (Eds.), Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Iceland J, Weinberg DH, & Steinmetz E (2002). Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation in the United States: 1980–2000. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, Bowden J, & Baker R (2010). How does the DerSimonian and Laird procedure for random effects meta-analysis compare with its more efficient but harder to compute counterparts? Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 140(4), 961–970. doi:DOI 10.1016/j.jspi.2009.09.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee KD, & Perloff JD (2003). An ecological analysis of racial differences in low birthweight: implications for maternal and child health social work. Health and Social Work, 28(1), 9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janevic T, Stein CR, Savitz DA, Kaufman JS, Mason SM, & Herring AH (2010). Neighborhood deprivation and adverse birth outcomes among diverse ethnic groups. Annals of Epidemiology, 20(6), 445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MA, & Marchi KS (2009). Segmented assimilation theory and perinatal health disparities among women of Mexican descent. Social Science and Medicine, 69(1), 101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T, Drisko J, Gallagher K, & Barela C (1999). Low birth weight: A women's health issue. Women's Health Issues, 9(5), 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent ST, McClure LA, Zaitchik BF, & Gohlke JM (2013). Area-level risk factors for adverse birth outcomes: trends in urban and rural settings. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13, 129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M, Dunlop A, & Hogue C (2014). Measuring Women's Cumulative Neighborhood Deprivation Exposure Using Longitudinally Linked Vital Records: A Method for Life Course MCH Research. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(2), 478–487. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1244-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MR, Cooper HL, Drews-Botsch CD, Waller LA, & Hogue CR (2010). Metropolitan isolation segregation and Black-White disparities in very preterm birth: a test of mediating pathways and variance explained. Social Science and Medicine, 71(12), 2108–2116. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger DJ, Munsell MA, & French-Turner T (2011). Using a life history framework to understand the relationship between neighborhood structural deterioration and adverse birth outcomes. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 5(4), 260–274. [Google Scholar]

- Love C, David RJ, Rankin KM, & Collins JW Jr (2010). Exploring weathering: Effects of lifelong economic environment and maternal age on low birth weight, small for gestational age, and preterm birth in African-American and white women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172(2), 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZC, Wilkins R, & Kramer MS (2006). Effect of neighbourhood income and maternal education on birth outcomes: a population-based study. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(10), 1415–1420. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X (2013). Food environment and birth outcomes in South Carolina. (3593118 PhD Dissertation), University of South Carolina, Ann Arbor, MI: Retrieved from http://pitt.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1440113717?accountid=14709 ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Full-text database. [Google Scholar]

- Madkour AS, Harville EW, & Xie Y (2014). Neighborhood disadvantage, racial concentration and the birthweight of infants born to adolescent mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(3), 663–671. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1291-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair C, & Gruenewald P (2011). Environmental correlates of low birth weight racial/ethnic disparities in California. American Journal of Epidemiology, 173, S133. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJK, & Mathews TJ (2013). Births: Final Data for 2011. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi CM, Hawkley LC, Piotrowski ZH, & Pickett KE (2007). Neighborhood economic disadvantage, violent crime, group density, and pregnancy outcomes in a diverse, urban population. Social Science and Medicine, 65, 2440–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SM, Kaufman JS, Daniels JL, Emch ME, Hogan VK, & Savitz DA (2011a). Black preterm birth risk in nonblack neighborhoods: effects of Hispanic, Asian, and non-Hispanic white ethnic densities. Annals of Epidemiology, 21(8), 631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SM, Kaufman JS, Daniels JL, Emch ME, Hogan VK, & Savitz DA (2011b). Neighborhood ethnic density and preterm birth across seven ethnic groups in New York City. Health & Place, 17(1), 280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SM, Kaufman JS, Emch ME, Hogan VK, & Savitz DA (2010). Ethnic density and preterm birth in African-, Caribbean-, and US-born non-Hispanic black populations in New York City. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172(7), 800–808. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SM, Messer LC, Laraia BA, & Mendola P (2009). Segregation and preterm birth: the effects of neighborhood racial composition in North Carolina. Health & Place, 15(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez DD, Hogan VK, & Culhane J (2011). Institutional racism and pregnancy health: using Home Mortgage Disclosure act data to develop an index for Mortgage discrimination at the community level. Public Health Reports, 126 Suppl 3, 102–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Kaufman JS, Dole N, Herring A, & Laraia BA (2006). Violent crime exposure classification and adverse birth outcomes: a geographically-defined cohort study. International Journal of Health Geographics, 5, 22. doi: 10.1186/1476-072x-5-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Kaufman JS, Dole N, Savitz DA, & Laraia BA (2006). Neighborhood crime, deprivation, and preterm birth. Annals of Epidemiology, 16(6), 455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Kaufman JS, Mendola P, & Laraia BA (2008). Black-white preterm birth disparity: a marker of inequality. Annals of Epidemiology, 18(11), 851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Oakes JM, & Mason S (2010). Effects of socioeconomic and racial residential segregation on preterm birth: a cautionary tale of structural confounding. American Journal of Epidemiology, 171(6), 664–673. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Vinikoor LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, Eyster J, Holzman C, et al. (2008). Socioeconomic domains and associations with preterm birth. Social Science and Medicine, 67(8), 1247–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina LC, & Kramer MR (2013). Multilevel analysis of small area violent crime and preterm birth in a racially diverse urban area. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 12(4), 445–455. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe A, Lail P, Ghali WA, & Sauve RS (2011). The association between neighbourhoods and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of multi-level studies. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 25(3), 236–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda ML, Messer LC, & Kroeger GL (2012). Associations between the quality of the residential built environment and pregnancy outcomes among women in North Carolina. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(3), 471–477. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & Group P (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD (2003). Neighborhood mechanisms and the spatial dynamics of birth weight. American Journal of Sociology, 108(5), 976–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumbare SS, Maindarkar G, Darade R, Yenge S, Tolani MK, & Patole K (2012). Maternal risk factors associated with term low birth weight neonates: a matched-pair case control study. Indian Pediatrics, 49(1), 25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah-Amankra S (2010). Neighborhood contextual factors, maternal smoking, and birth outcomes: multilevel analysis of the South Carolina PRAMS survey, 2000-2003. Journal of Women's Health, 19(8), 1543–1552. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah-Amankra S, Dhawain A, Hussey J, & Luchok KJ (2010). Maternal Social Support and Neighborhood Income Inequality as Predictors of Low Birth Weight and Preterm Birth Outcome Disparities: Analysis of South Carolina Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System Survey, 2000-2003. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(5), 774–785. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0508-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah-Amankra S, Luchok KJ, Hussey JR, Watkins K, & Liu X (2010). Effects of maternal stress on low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes across neighborhoods of South Carolina, 2000-2003. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(2), 215–226. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0447-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Campo P, Burke JG, Culhane J, Elo IT, Eyster J, Holzman C, et al. (2008). Neighborhood deprivation and preterm birth among non-Hispanic Black and White women in eight geographic areas in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 167(2), 155–163. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Campo P, Caughy MOB, Aronson R, & Xue X (1997). A comparison of two analytic methods for the identification of neighborhoods as intervention and control sites for community-based programs. Evaluation and Program Planning, 20(4), 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- O'Campo P, Xue X, Wang M, & Coughy MO (1997). Neighborhood risk factors for low birthweight in Baltimore: a multilevel analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 87(7), 1113–1118. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.7.1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Crespo MR, Narla NP, Williams AR, Beebe TJ, Sloan J, Yawn BP, et al. (2013). Comparison of individual-level versus area-level socioeconomic measures in assessing health outcomes of children in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(4), 305–310. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GS, Wise LA, Rich-Edwards JW, Stampfer MJ, & Rosenberg L (2009). Income incongruity, relative household income, and preterm birth in the Black Women's Health Study. Social Science and Medicine, 68(12), 2122–2128. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GS, Wise LA, Rich-Edwards JW, Stampfer MJ, & Rosenberg L (2013). Neighborhood socioeconomic status in relation to preterm birth in a U.S. cohort of black women. Journal of Urban Health, 90(2), 197–211. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9739-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett KE, Ahern JE, Selvin S, & Abrams B (2002). Neighborhood socioeconomic status, maternal race and preterm delivery: A case-control study. Annals of Epidemiology, 12(6), 410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett KE, Collins JW Jr., Masi CM, & Wilkinson RG (2005). The effects of racial density and income incongruity on pregnancy outcomes. Social Science and Medicine, 60(10), 2229–2238. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce NA, Hoggatt KJ, Wilhelm M, & Ritz B (2005). Preterm birth: the interaction of traffic-related air pollution with economic hardship in Los Angeles neighborhoods [corrected] [published erratum appears in AM J EPIDEMIOL 2010 Jun 1;171(11):1248]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 162(2), 140–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh VA, Andrews HF, & Garfinkel RS (2001). The contribution of maternal age to racial disparities in birthweight: a multilevel perspective. American Journal of Public Health, 91(11), 1815–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan PB, & Salsberry PJ (2005). Race and ethnic differences in determinants of preterm birth in the USA: broadening the social context. Social Science and Medicine, 60, 2217–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SZ (2012). The impact of segregation and education on levels of maternal risk and their joint contribution to the risk of preterm birth in North Carolina. (3509300 PhD Dissertation), The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Ann Arbor, MI: Retrieved from http://pitt.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1019237109?accountid=14709 ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Full-text database. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, & Hamilton ER (2009). Effects of neighborhood racial composition on birthweight. Health & Place, 15(3), 814–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich-Edwards JW, Buka SL, Brennan RT, & Earls F (2003). Diverging associations of maternal age with low birthweight for black and white mothers. International Journal of Epidemiology, 32(1), 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard M (2006). Racial disparities, birth outcomes, and changing demographics of East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana. (3244987 PhD dissertation), Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College, Ann Arbor, MI: Retrieved from http://pitt.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/305322849?accountid=14709 ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Full-text database. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts EM (1997). Neighborhood social environments and the distribution of low birthweight in Chicago. American Journal of Public Health, 87(4), 597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondo PH, Ferreira RF, Nogueira F, Ribeiro MC, Lobert H, & Artes R (2003). Maternal psychological stress and distress as predictors of low birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57(2), 266–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schempf A, Kaufman JS, Messer LC, & Mendola P (2011). The neighborhood contribution to black-white perinatal disparities: an example from two north Carolina counties, 1999-2001. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174(6), 744–752. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schempf A, Strobino D, & O'Campo P (2009). Neighborhood Effects on Birthweight: An Exploration of Psychosocial and Behavioral Pathways in Baltimore, 1995–1996. Social Science and Medicine, 68(1), 100–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims M, & Rainge Y (2002). Urban poverty and infant-health disparities among African Americans and whites in Milwaukee. Journal of the National Medical Association, 94(6), 472–479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims M, Sims TH, & Bruce MA (2007). Community income, smoking, and birth weight disparities in Wisconsin. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association, 18(2), 16–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims M, Sims TL, & Bruce MA (2008). Race, ethnicity, concentrated poverty, and low birth weight disparities. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association, 19(1), 12–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South AP, Jones DE, Hall ES, Huo S, Meinzen-Derr J, Liu L, et al. (2012). Spatial analysis of preterm birth demonstrates opportunities for targeted intervention. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(2), 470–478. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0748-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, & Graham E (2010). Preterm birth: An overview of risk factors and obstetrical management. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 16(4), 285–288. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. (2000). Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283(15), 2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutz KL, Dozier AM, van Wijngaarden E, & Glantz JC (2012). Birth outcomes across three rural-urban typologies in the Finger Lakes region of New York. Journal of Rural Health, 28(2), 162–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00392.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Chen JT, Rehkopf DH, Waterman PD, & Krieger N (2006). Comparing individual- and area-based socioeconomic measures for the surveillance of health disparities: A multilevel analysis of Massachusetts births, 1989-1991. American Journal of Epidemiology, 164(9), 823–834. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper NK, Farr SL, Cohen BB, Nannini A, Zhang Z, Anderson JE, et al. (2012). Singleton preterm birth: risk factors and association with assisted reproductive technology. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(4), 807–813. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0787-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramer MR, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, & McQuay HJ (1997). Impact of covert duplicate publication on meta-analysis: a case study. The BMJ, 315(7109), 635–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinikoor-Imler L, Messer L, Evenson K, & Laraia B (2011). Neighborhood conditions are associated with maternal health behaviors and pregnancy outcomes. Social Science and Medicine, 73(9), 1302–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinikoor LC, Kaufman JS, MacLehose RF, & Laraia BA (2008). Effects of racial density and income incongruity on pregnancy outcomes in less segregated communities. Social Science and Medicine, 66(2), 255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos AA, Posthumus AG, Bonsel GJ, Steegers EA, & Denktas S (2014). Deprived neighborhoods and adverse perinatal outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 93(8), 727–740. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E, Hernandez AV, & Kattan MW (2008). Meta-analysis: Its strengths and limitations. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 75(6), 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D (2011). Discriminatory mass de-housing and low-weight births: scales of geography, time, and level. Journal of Urban Health, 88(3), 454–468. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9581-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M, Harville E, Theall K, Webber L, Chen W, & Berenson G (2013). Neighborhood poverty, allostatic load, and birth outcomes in African American and white women: findings from the Bogalusa Heart Study. Health & Place, 24, 260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JC (2010). Maternal capital and the metabolic ghetto: An evolutionary perspective on the transgenerational basis of health inequalities. American Journal of Human Biology, 22(1), 1–17. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. ( 2002). Meeting of Advisory Group on Maternal Nutrition and Low Birthweight Retrieved from Geneva, Switzerland: [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Bazer FW, Cudd TA, Meininger CJ, & Spencer TE (2004). Maternal nutrition and fetal development. Journal of Nutrition, 134(9), 2169–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.