Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), is causing a dramatic pandemic.1 Lombardy, in northern Italy, is one of the most affected regions worldwide.2 Cardiovascular complications occur frequently in patients with COVID-19,3 with challenges in acute management. We aimed to evaluate incidence, clinical presentation, angiographic findings, and clinical outcomes of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in patients with COVID-19.

All hospitals with catherization laboratories in Lombardy were contacted to collect cases of patients with confirmed COVID-19 who underwent an urgent coronary angiogram because of STEMI between February 20, 2020 (date of first COVID-19 case in Lombardy) and March 30, 2020.2 Data were collected retrospectively, in anonymized fashion without any sensitive data, therefore not requiring institutional review board approval. COVID-19 was confirmed with reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction assays. STEMI was defined based on the presence of typical symptoms associated with ST-segment elevation or new left bundle-branch block.4 A stenosis was considered as the culprit lesion in case of angiographic evidence of thrombotic occlusion/subocclusion. Obstructive coronary artery disease was defined based on the angiographic evidence of a stenosis >50% on visual estimation.

A total of 28 patients with COVID-19 with STEMI were included. All patients met the guideline definition of STEMI4 with localized ST-elevation (25 patients, 89.3%) or new left bundle-branch block (3 patients, 10.7%), and all were treated in the setting of emergent activation.

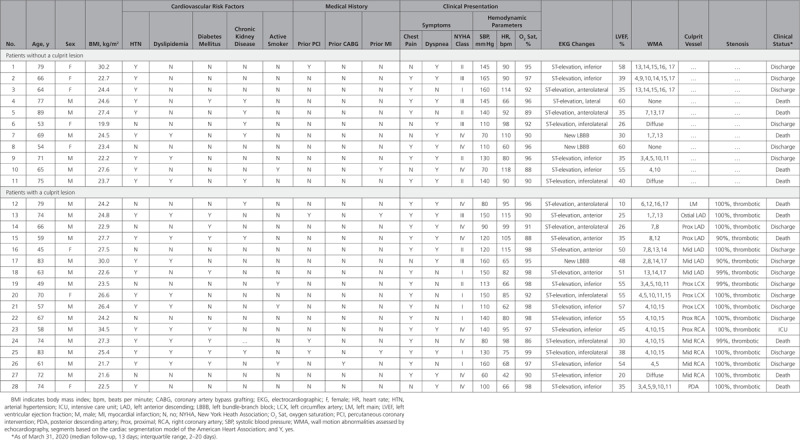

The Table displays a detailed overview of each included patient. The mean age was 68±11 years, 8 patients (28.6%) were women, 20 (71.4%) had arterial hypertension, 9 (32.1%) had diabetes mellitus, 8 (28.6%) had chronic kidney disease, and 3 (10.7%) had a previous myocardial infarction.

Table.

Overview of Included Patients

For 24 patients (85.7%), the STEMI represented the first clinical manifestation of COVID-19, and they did not have a COVID-19 test result at the time of coronary angiography. The remaining 4 patients had STEMI during hospitalization for COVID-19. Twenty-two patients (78.6%) presented with typical chest pain associated with or not associated with dyspnea, and 6 patients (21.4%) had dyspnea without chest pain.

On echocardiography, 23 patients (82.1%) had localized wall motion abnormalities, 3 (10.7%) had diffuse hypokinesia, and 2 (7.1%) did not have abnormalities. The left ventricular ejection fraction was <50% in 17 patients (60.7%).

All patients underwent urgent coronary angiography, and none was treated with fibrinolysis. Out of 28 patients, 17 patients (60.7%) had evidence of a culprit lesion requiring revascularization, and 11 patients (39.3%) did not have obstructive coronary artery disease.

As of March 31, 2020 (median follow-up, 13 days; interquartile range, 2–20 days), 11 patients (39.3%) had died, 1 (3.6%) was still hospitalized in an intensive care unit, and 16 (57.1%) had been discharged.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, the regional STEMI network was reorganized,2 and we have observed a reduction in the number of patients presenting with STEMI. Both factors might have contributed to the relatively low number of cases observed during the study period. However, considering the cardiovascular risk profile of patients with COVID-19, many of these are expected to have STEMI in the coming months. Evidence-based strategies are mandatory to guide their clinical management. Our findings provide relevant evidence showing that, although all patients had a typical STEMI presentation, angiography demonstrated the absence of a culprit lesion in 39.3% of cases, therefore excluding a type 1 myocardial infarction.

A recent document from the American College of Cardiology’s Interventional Council and the Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention discusses how to guarantee state-of-the-art treatment as well as the safety of healthcare providers involved in management of STEMI in the context of a COVID-19 outbreak.3 The document recommends weighing carefully the balance between healthcare provider exposure and patient benefit. Our findings underscore that all efforts should be made to differentiate between type 2 myocardial infarctions and myocarditis versus type 1 myocardial infarctions.

Our findings also show that a strategy relying on systematic fibrinolysis5 is not justified because reperfusion appears not to be required in a significant proportion of patients with COVID-19 with STEMI.

We acknowledge that this is an early report on a relatively small number of patients. However, we wish to underscore that we systematically collected data on patients with COVID-19 with STEMI in Lombardy during the first 6 weeks of the outbreak.

In patients in whom a culprit lesion was excluded by coronary angiography, we were unable to determine whether the clinical presentation was caused by a type 2 myocardial infarction, a myocarditis subsequent to SARS-CoV-2 infection, SARS-CoV-2–related endothelial dysfunction, or a cytokine storm. Further investigations are needed to fully elucidate the pathophysiology of myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19.

In conclusion, our findings show that STEMI may represent the first clinical manifestation of COVID-19. In approximately 40% of patients with COVID-19 with STEMI, a culprit lesion is not identifiable by coronary angiography. A dedicated diagnostic pathway should be delineated for patients with COVID-19 with STEMI, aimed at minimizing patients’ procedural risks and healthcare providers’ risk of infection.

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request by email.

References

- 1.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, et al. China Medical Treatment Expert Group for; COVID-19. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stefanini GG, Azzolini E, Condorelli G. Critical organizational issues for cardiologists in the COVID-19 outbreak: a frontline experience from Milan, Italy. Circulation. 2020;141:1597–1599. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welt FGP, Shah PB, Aronow HD, Bortnick AE, Henry TD, Sherwood MW, Young MN, Davidson LJ, Kadavath S, Mahmud E, et al. American College of Cardiology’s Interventional Council and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: from the ACC’s Interventional Council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2372–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng J, Huang J, Pan L. How to balance acute myocardial infarction and COVID-19: the protocols from Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital [published online March 11, 2020]. Intensive Care Med. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05993-9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05993-9. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00134-020-05993-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]