Abstract

The COVID-19 outbreak has sown clinical and administrative chaos at academic health centers throughout the country. As COVID-19-related burdens on the health care system and medical schools piled up, questions from medical students far outweighed the capacity of medical school administrators to respond in an adequate or timely manner, leaving students feeling confused and without clear guidance. In this Perspective, incoming and outgoing executive leaders of the University of Michigan Medical School Student Council and medical school deans outline the specific ways they were able to bridge the gap between medical students and administrators in a time of crisis. To illustrate the value of student government during uncertain times, the authors identify the most pressing problems faced by students at each phase of the curriculum—preclerkship, clerkship, and postclerkship—and explain how Student Council leadership partnered with administrators to find creative solutions to these problems and provide guidance to learners. They end by reflecting on the role of student government more broadly, identifying 3 guiding principles of student leadership and how these principles enable effective student representation.

Preparing for and responding to the COVID-19 outbreak has pushed hospitals across the country to their clinical and administrative capacities. This has forced rapid and dramatic changes in medical education. When state and local governments started issuing stay-at-home orders and closing schools and universities, a majority of medical schools moved their preclerkship curricula entirely online in less than a week and suspended clinical duties for clerkship and postclerkship students. Schools moved assessments from structured, proctored settings to remote proctored or unproctored administrations. United States Medical Licensing Examinations were canceled by the National Board of Medical Examiners due to closures of both Prometric and Clinical Skills Evaluation Collaboration centers.1,2 These unprecedented changes have led to immense confusion, frustration, and panic among medical students.

As new data have emerged day by day, hour by hour, and minute by minute, schools and national organizations have been caught in cycles of reactionary change, torn between a desire to preserve the education of medical students and the need to protect the public by flattening the curve. Administrators often have been compelled to make swift, decisive decisions in the face of great uncertainty. They have made major and seemingly minor changes with the potential for immense downstream consequences.

During this time, students have often found themselves reading email guidance from a course/clerkship director or dean, only to see contradictory guidance moments later from another source on their Twitter or Instagram feed. Learners crave concrete answers to both short- and long-term questions: How long will classes be on hold? Will clerkship grades go pass/fail? How might the lack of traditional learning opportunities (e.g., a subinternship, an away rotation, a research month) impact residency applications? Will some students continue to graduate early to fulfill workforce demands?

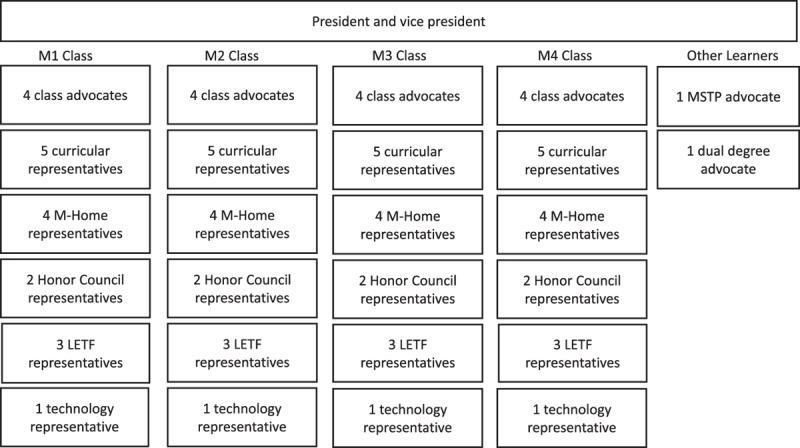

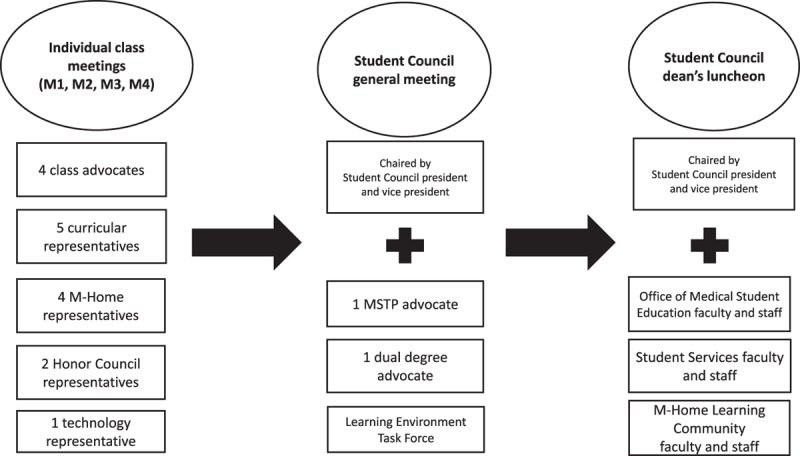

At our institution, we also began to consider how the next decisions and actions related to medical education in the time of COVID-19 could accommodate the disparate needs of approximately 800 University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS) students and remain equitable. The UMMS Student Council, an elected student government made up of over 60 members across the student body, has served as the liaison between students and the medical school administration for more than 60 years (Figures 1 and 2). This symbiotic relationship between students and administrators3–5 has allowed students to help shape every aspect of the UMMS curriculum. These efforts typically unfold over time, allowing for broad student input and the opportunity for students to ask critical questions. The response to COVID-19, however, has required rapid decision making in a time of rapid change and uncertainty, and because of the immense new clinical and administrative burdens, faculty and administrators have not had their usual capacity to gather and respond to the varied opinions within the student body. In response to the need for student input, UMMS Student Council stepped up to provide a direct, curated, and manageable pipeline of student information, increasing the capacity of the administration to respond to student concerns by relying on medical student leaders to represent the student experience.

Figure 1.

University of Michigan Medical School Medical Student Council organizational chart. All representatives are elected by their respective classes. Each month, each class meets individually to identify issues before the class. These are discussed at a meeting of all student representatives, and specific issues are then brought forward at a monthly luncheon with medical school administrators. Abbreviations: M1, first-year student; M2, second-year student; M3, third-year student; M4, fourth-year student; LETF, Learning Environment Task Force; MSTP, Medical Scientist Training Program; M-Home, Medical School Home, the UMMS house-based longitudinal learning communities.

Figure 2.

University of Michigan Medical School Student Council monthly structure. In a typical month, each class meets individually to identify class-specific issues. These are brought to a meeting of all members of Student Council, where general issues and class-specific issues are discussed and solutions proposed. Finally, some members of Student Council present the issues and potential solutions to a monthly luncheon with medical school administrators. Abbreviations: M1, first-year student; M2, second-year student; M3, third-year student; M4, fourth-year student; MSTP, Medical Scientist Training Program; M-Home, Medical School Home, the UMMS house-based longitudinal learning communities; LETF, Learning Environment Task Force.

In this Perspective, we outline the curricular changes and challenges experienced by medical students at UMMS in the wake of COVID-19, and the ways in which our medical student government partnered during the crisis with medical school administration to offer creative solutions to these problems. We focus on the most pressing issues and their respective solutions faced by students in each phase of medical education (preclerkship, clerkship, and postclerkship). Finally, we end by reflecting on the role of student leadership in a time of fear and uncertainty and the value added by a strong relationship between student government and medical school administration.

Preclerkship Experience

The first problem faced by preclerkship (i.e., first-year) students was the transition to virtual learning. From an administrative perspective, the preclerkship curriculum was the easiest to adapt in response to COVID-19. Didactic lectures were already recorded and available for online streaming, meaning the main administrative changes were finding replacements for various in-person requirements like patient presentations, anatomy dissections, small-group discussions, and standardized patient encounters. This context allowed the administration to shift to remote learning with less than 24 hours’ notice.

The workload and pace of the curriculum, however, did not slow down, and preclerkship students needed time to adjust. Students became overwhelmed balancing the rigorous demands of the curriculum while simultaneously fielding questions from family members, following the news, troubleshooting technological failures, and checking frequent email updates from faculty. Stress levels impeded students’ ability to engage with the curriculum,6,7 so Student Council prioritized mitigating cognitive load. Student Council met with the dean for curriculum and preclerkship course directors to find creative ways to reduce curricular burden while ensuring learners achieved the educational program objectives (i.e., competencies). Together, they identified content and assignments to be merged, eliminated, or postponed. Student leaders also worked with course directors to streamline communication, creating a weekly summary—a “one-stop shop”—for students to review all upcoming lectures, assignments, and deadlines. More urgent communications were collated centrally and sent once daily by the administrator of the preclinical curriculum, while faculty and staff were instructed to minimize other email traffic.

Separate from immediate academic concerns, preclerkship students faced an existential question of their role during a pandemic in the greater health care community. Student Council representatives identified preclerkship students’ calling to serve and, in response, organized student efforts, partnering with the administration to create a living document of nonclinical opportunities for students to support the community. This document ultimately included over 50 volunteer opportunities with the contact information of community leaders in need of help. Opportunities included providing free childcare for health care workers during widespread school closures, delivering groceries and meals to those in need, and organizing blood donations to address critical shortages. Student Council was instrumental in creating and moderating this easily accessible document, ensuring all students could get involved in community pandemic response efforts.

Clerkship Experience

Clerkship students (i.e., second-year students) were subject to some of the greatest disruptions to their learning, and the main function of Student Council was to provide clear and swift communication to mitigate the confusion during a time of rapid change.

The most immediate problem faced by clerkship students was how to continue learning safely in the clinical environment. As national COVID-19 concerns began to escalate, UMMS administrators initially chose not to remove students from the clinical environment. At UMMS, a guiding principle is that medical students are considered essential members of the health care team. Thus, deans and clerkship directors decided to continue clinical rotations to facilitate learning and to allow students to serve patients and the public during this unparalleled time. The administration used the leadership principle of “starting with why” (i.e., students are essential members of the health care team) in all their communications.8,9 Recognizing that some students were uncomfortable with the administration’s decision to keep students clinically active, Student Council partnered with the administration to provide student input on new clinical student guidelines to maximize safety. These guidelines included (1) prohibiting students from providing direct care for COVID-19-positive patients or persons-under-investigation to minimize student exposure and conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) and (2) encouraging students to self-isolate for any personal or family medical comorbidities. Effectively communicating these guidelines to all students and ensuring their understanding, in the context of fear and constant change, required a large coordinated effort by Student Council representatives. These efforts helped assuage many student concerns while advocating for their safe inclusion in the clinical space.

Although the administration’s goal was to keep students safely on rotations, plans needed to change quickly after the Association of American Medical Colleges’ (AAMC’s) sudden announcement recommending removal of students from clinical duties.10 Despite language indicating the note was intended as guidance, the boldfaced wording in the statement was clear, using language such as “immediately,” “strongly support,” and “a minimum a 2-week suspension.” News of the announcement and ensuing rumors instantly circulated among the student body, sowing chaos and leaving students in the dark about how to proceed. Senior medical school leadership rapidly convened to discuss the AAMC guidelines in the context of UMMS’s aforementioned principles. After careful consideration of all factors, medical school leadership decided to suspend clinical student rotations. They needed time to coordinate with clerkship directors to create a plan to withdraw students in a manner that would not negatively impact patient care.

The urgency of the situation required rapid communication. To fill this information vacuum, members of Student Council worked quickly with administrators to identify critical information needed by students in the short term. Student Council then used social media, group chats, and other informal means of communication that students frequently monitor more frequently than email to ensure rapid and widespread delivery. This information from Student Council went out to students within an hour of the AAMC announcement and filled the communication void until more formal instructions from clerkships could be delivered.

This scenario exemplifies how effective student representatives can be at serving as the liaison between administration and students. By understanding the immediate needs of students, Student Council was able to use established relationships with the administration to provide answers and ultimately functioned as a valuable resource by using effective student-preferred modes of communication.

Postclerkship Experience

The remaining students (i.e. third- and fourth-year students) had completed their core clerkships and were therefore more poised to assist the hospital system but were not in a position to help without the structure of clinical electives. There was an immense outpouring of desire among students to serve as volunteers for a health care system under stress. Student Council, sensing this groundswell, sought to unify and centralize volunteer efforts. As a culmination of this effort, the day after students were pulled from the wards, the “M-Response Corps”—a group of student volunteers committed to offering their time and talents to the greater health care system—was launched by Student Council representatives with support from faculty and administration. Members of the M-Response Corps received accelerated training to provide much-needed services, such as phone triage, specimen processing, and PPE donation gathering. Individual students also worked with faculty members to identify hospital needs and create new clinical opportunities, such as a respiratory therapist extender curriculum. As the initiative grew, all UMMS students were invited to join the M-Response Corps, eventually including over 500 students from across the student body. The M-Response Corps illustrates how students and the administration partnered to maintain fundamental UMMS principles, like the importance of service as a calling in our profession, while respecting restrictions related to working in the clinical environment.

Separate from clinical responsibilities and volunteering, graduating students preparing to match into residency programs were saddened to learn that the traditional 750-plus person Match Day celebration would be canceled due to COVID-19 physical distancing requirements. Medical training requires self-sacrifice and delayed gratification, and graduating students had to sacrifice the long-awaited acknowledgment and celebration of their accomplishments. In response to this sense of loss, the Student Council-led Match Day Planning Committee—in partnership with the Michigan Medicine Communications Department and the Office of Medical Student Education—sought to preserve this important tradition by shifting the highly anticipated Match Day celebration entirely online with less than a week’s notice. To make the transition as seamless as possible, students identified the core elements of Match Day that would be necessary for a successful transition to an online celebration. The most important elements were a common “virtual” space for students to gather and feel part of a larger community, a way to deliver messages from deans and faculty meant to honor these students, and a way for graduates to share their information so members of the community could connect with them directly. To achieve these goals, students created a website where deans, faculty, and other mentors could upload congratulatory videos while allowing students to share news with one another. These creative solutions provided comfort for students who desired to celebrate in front of peers, friends, and family, but ultimately recognized that a traditional celebration was in direct conflict with the same public health measures they entered this profession to uphold.

Reflection on the Role of Student Leadership

At its core, the purpose of medical student government is to advocate for the needs of the student body to the medical school administration, facilitating the learning, development, and empowerment of all students.11–13 Student Council has a long-standing history of advocating for students at UMMS and has served a vital role in crucial medical school processes, such as a recent major curricular transformation14 and an upcoming Liaison Committee on Medical Education site visit. The administration at UMMS embraces this student government partnership, as we all strive to improve student education and professional development, training outstanding physicians, leaders, and change agents.

Having an established relationship of trust between Student Council and the administration has enhanced our ability to represent and advocate for the student body in a time of crisis where decisions must be made and communicated quickly, often with incomplete information. We believe that all medical schools would benefit from an active student government that builds trusting relationships with administrators. Such a partnership can make a significant impact on students and administrators alike. Reflecting on our experiences as both incoming and outgoing Student Council executive leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic response, we have identified 3 fundamental principles that helped guide us as student leaders in a time of upheaval. These principles may help guide other student leaders facing similar situations in the future.

First, recognize and embrace that a crisis necessitates changes to the status quo. As COVID-19 pushed the hospital system to its limits, the entire context of medical education moved from a state of predictability to one of flux. This required all members of the learning community to change expectations of how decisions would be made, implemented, and communicated. Unable to provide certainty, we leaned in, explaining the reasoning behind decisions as best as possible and clearly stating when there were questions that were impossible to answer. Forecasting too far into the future could have confounded rather than clarified concerns as new information became available. By recognizing this paradigm shift from certainty to fluidity, we were able to provide information in a way that acknowledged the breadth of concerns while also accurately reflecting the reality of the situation.

Second, the demand for—and value of—clear communication increases in times of crisis. With changes occurring sometimes as frequently as hourly, students’ desire for communication of information outweighs the capacity to find answers to the hundreds of questions they posed. Yet we were committed to ensuring all students’ opinions were heard, and creating pathways for students to voice their concerns empowers all students and provides some peace of mind in uncertain times. We created a school-wide survey asking students to provide questions and comments and distributed it multiple times each week. We reviewed every comment and used this information to guide our agenda with the administration. We responded to the most common themes in weekly class-specific emails. In addition, student feedback and questions were shared with the associate dean for medical student education, who converted his weekly in-person “Open Dialogue” sessions to twice-weekly “Virtual Dialogue” videos and live events where he responded to common concerns. Feelings of helplessness among our peers have been inevitable given the tumult surrounding COVID-19 and its impact on learners, but through frequent and honest communication, we believe we have been able to partner with administration to assure our classmates that their concerns were at least being heard.

The final—and perhaps most vital—principle is the importance of teamwork. Student Council is an elected representative body of student leaders representing the entire curriculum and medical school communities, working together as a team. As the COVID-19 pandemic changed all domains of our lives, it progressively and irreversibly impacted every phase of the curriculum. Not only did students begin to worry about their families and loved ones, but they also worried about the effect these fundamental changes would have on their education and future careers. A first-year student might fail her neurology exam because she is glued to the news and worried about her grandmother’s ability to get groceries. A fourth-year student might be anxiously wondering how his intern year will differ from that of his predecessors in light of grim projections of overwhelmed hospital systems and an exhausted workforce. Being able to convey the broad needs of the student body during this crisis was only possible thanks to every member of Student Council rising to the challenge of supporting their peers in times of uncertainty.

COVID-19 has presented the greatest challenge to our student body in recent memory. Due in large part to a long-standing relationship of trust with our medical school administrators, the UMMS Student Council has been able to advocate for the needs of students during a period of unprecedented challenge. By holding the purpose of Student Council—to represent the needs of students and facilitate their learning and well-being—at the core of our decision making, we have been able to identify challenges faced by students and quickly implement solutions. Behind every curricular transition, communication gap, organized volunteer effort, or moral conflict, there was a dedicated and effective student team that devoted entire days, even weeks, to resolving the issues and facilitating the best solutions available to us. It is with great appreciation for our Student Council teammates, whose commitment to the student body is a daily inspiration, that we acknowledge the privilege and responsibility of representation and leadership, which starts and ends with our peers.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank all the members of the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS) Student Council for their contributions to the student body. They would specifically like to thank Nicole Dayton, Michael Broderick, and Deborah Berman, MD, who have spearheaded the M-Response Corps alongside A. Hammoud and N.I. Ibrahim. They thank Kate Kollars for reviewing the manuscript. They thank all members of the UMMS administration, including house counselors, faculty, staff, and the deans, who have all made immense personal sacrifices on behalf of students. They would also like to thank Brad Densen and Denise Brennan specifically for their thoughtfulness and friendship. And finally, they would like to broadly recognize the UMMS medical student body, who has banded together for the benefit of all during a difficult time.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

References

- 1.United States Medical Licensing Examination. USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) testing suspension to continue through May 31, 2020. https://www.usmle.org/announcements/?ContentId=266. Published March 13, 2020; updated April 3, 2020. Accessed June 1, 2020.

- 2.United States Medical Licensing Examination. Coronavirus (COVID-19) 4/10/2020 update: Prometric closures and Step 1, Step 2 CK, and Step 3. United States Medical Licensing Examination. https://www.usmle.org/announcements/?ContentId=268. Published March 17, 2020; updated April 10, 2020. Accessed June 1, 2020.

- 3.Lizzio A, Wilson K. Student participation in university governance: The role conceptions and sense of efficacy of student representatives on departmental committees. Stud High Educ. 2009;34:69–84. 10.1080/03075070802602000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey P. Representation and student engagement in higher education: A reflection on the views and experiences of course representatives. J Furth High Educ. 2013;37:71–88. 10.1080/0309877X.2011.644775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subramanian J, Anderson VR, Morgaine KC, Thomson WM. The importance of ‘student voice’ in dental education. Eur J Dent Educ. 2013;17:e136–e141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart SM, Lam TH, Betson CL, Wong CM, Wong AM. A prospective analysis of stress and academic performance in the first two years of medical school. Med Educ. 1999;33:243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitaliano PP, Maiuro RD, Russo J, Mitchell ES, Carr JE, Van Citters RL. A biopsychosocial model of medical student distress. J Behav Med. 1988;11:311–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinek S. Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. 2009New York, NY: Portfolio; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinek S. Why Good Leaders Make You Feel Safe [video]. Ted. March 2014. https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_sinek_why_good_leaders_make_you_feel_safe#t-265124. Accessed June 1, 2020.

- 10.Whelan A, Prescott J, Young G, Catanese V. Guidance on Medical Students’ Clinical Participation in Direct Patient Contact Activities. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-03/Guidance%20on%20Student%20Clinical%20Participation%203.17.20%20Final.pdf. Published March 17, 2020; updated April 14, 2020. Accessed June 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visser K, Prince KJAH, Scherpbier AJJA, van der Vleuten CPM, Verwijnen MGM. Student participation in educational management and organization. Med Teach. 1998;20:451–454. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCullough A. The student as co-producer: Learning from public administration. about the student–university relationship. Stud High Educ. 2009;34:171–183. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bilodeau PA, Liu XM, Cummings BA. Partnered educational governance: Rethinking student agency in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94:1443–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurich D, Santen SA, Paniagua M, et al. Effects of moving the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 after core clerkships on Step 2 Clinical Knowledge performance. Acad Med. 2020;95:111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]