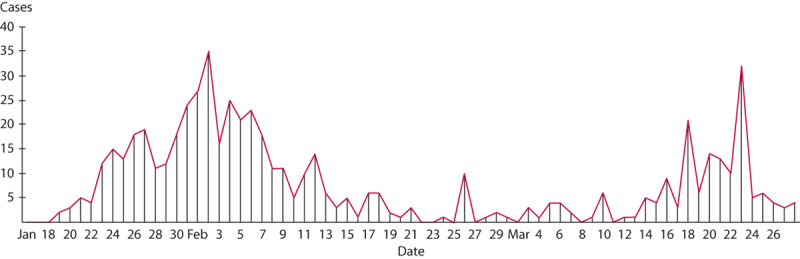

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)1 is a current pandemic with a mortality rate of 2.9%2 (7.7% in Italy3), and ≈9.8% of confirmed cases require ventilator support.2 Since its outbreak, it has presented countries with major political, scientific, and public health challenges. In Beijing, the escalating trend of COVID-19 lasted from January 19 to February 8, 2020, before the daily number of new cases stabilized (Fig. 1). In the initial stages, supplies of personal protective gear and test kits were in critical shortage, and the scarcity of laboratories that are capable of conducting COVID-19 tests also slowed down the molecular diagnosis of the virus. In the authors’ institution—a hospital with 2,200 beds—there have been only 339 nucleic acid tests to date.

FIGURE 1.

XXX.

Considering this sudden pandemic, what should surgeons do for surgical patients with varying needs? Elective operations for benign patients can be postponed, whereas elective operations for malignant patients and emergency procedures require thorough consideration. Emergency operations for malignant patients are pressing and usually demand immediate treatment. “When do we operate and when do we postpone?” is the question that every surgeon should contemplate.

Since the onset of the pandemic, no infections have been reported among surgery-related personnel in Beijing; furthermore, all patients with suspected COVID-19 infections who received surgical treatment tested negative afterward. In this commentary, we share our experiences, as well as lessons, from 11 medical centers in Beijing regarding the management of surgery-related issues against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic.

SURGERIES IN HOSPITALS DESIGNATED FOR COVID-19 PATIENTS

By March 21, there were 415 confirmed COVID-19 patients in Beijing Municipality.4 These patients were primarily treated by 2 designated infectious disease hospitals: Ditan Hospital and You’an Hospital. In retrospect, none of these patients received surgical intervention.

Regarding the phenomenon that confirmed COVID-19 patients hardly receive surgical treatment, there are several conceivable explanations. In the early phase of the pandemic, the potential risks of COVID-19 in surgical procedures were unknown, and most surgeons were extremely cautious about interventions. As the picture got clearer, demands for surgical intervention for patients with COVID-19 were postponed as often as possible, except for real emergencies, because treatments were primarily focused on the viral infection. Considering severe and critical patients, even if surgery was urgently needed, the primary goal was to protect patients’ lung functions rather than performing surgeries.

OPERATIONS IN REGULAR HOSPITALS IN BEIJING

Pre-escalation Phase (Before January 19)

Beijing’s first COVID-19 case was reported on January 19, 2020. Before this, all hospitals in Beijing were normally operational.

Escalation Phase (January 20 to February 8)

Because this period coincides with the Chinese Lunar New Year, there were fewer patients than usual. Across Beijing, 97 elective GI and colorectal cancer operations and 75 emergency operations were conducted during this period.

In the escalation phase, a major issue for all hospitals was the shortage of protective gear, which was prioritized for fever clinics and isolation wards, where potential COVID-19 patients were screened. Nearly all surgical departments in the city stopped elective surgery altogether because of the shortage. However, most emergency surgery departments remained operational.

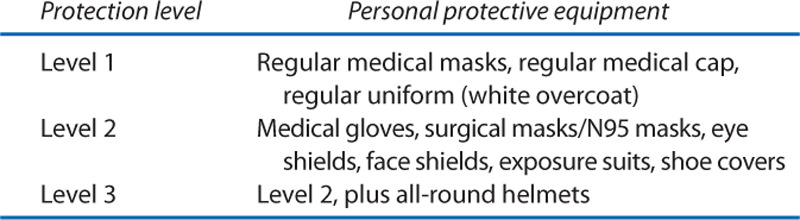

Generally, all hospitals in Beijing are equipped with fever clinics, and all patients with fever must be screened for COVID-19 (with chest CTs and nucleic acid tests if CTs indicate infection) at fever clinics before going to emergency or outpatient surgery departments. All patients to be admitted into surgical wards were required to be negative for all of the following examinations: epidemiological history, temperature tests, routine blood testing, and chest CT. During this period, most personnel—in the ward or in the operating theater—opted for level 1 protection (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Protection levels applied in China

The surgeons’ psychological reactions seemed to influence their clinical behaviors significantly. Approximately 10% of surgeons chose overprotection, with N95 masks and eye shields (level 2 protection) during surgery. Certain techniques were simplified, for example, anus-preserving procedures for patients with ultra-low rectal cancer were changed to abdominoperineal resections, and laparoscopic procedures were changed to open operations (because of concerns about potential aerosol transmission).

Postescalation Phase (February 9 to Present)

This phase is still ongoing, although confirmed COVID-19 cases are steadily declining. As the situation stabilizes, surgeons’ workload and morale are also recovering. Since the beginning of this phase, approximately 400 patients with GI and colorectal cancer were admitted to the surgical wards, of which more than 300 were for emergency surgery. Currently, the following protocols are implemented unanimously across our different centers:

Screening criteria for admission into surgical wards: patients’ epidemiological history and respiratory symptoms must be screened.5

Settings of rooms and beds: earlier in this period, there was 1 patient/bed per room; later, this was later revised to 2 patients/beds per room, with a distance of >1.5 m between the beds.

Protection of the surgeons during surgeries: surgical masks without eye shields.

Adaptations of technical requirements on the procedures: none; however, overly complicated surgeries are avoided (eg, combined organ resection, procedures with ultra-long durations, and those expected to require blood transmission of >1000 mL).

Management of postoperative fever: (1) postoperative fever (<38.5°C within 3 d after surgery): blood routine and frequent temperature tests; (2) postoperative fever with unknown reason (>38.5°C within 3 d after surgery or any fever beyond 3 d after surgery): relocate to single-bed room, prepare a special medical team for this patient, undertake chest CTs or even nucleic acid tests; (3) lung infection: isolation and preparation of an independent medical team for the patient, including 2 nurses and 1 surgeon, request assistance from department of respiratory diseases, undertake chest CTs or even nucleic acid tests.

As the mechanism and transmission channels of COVID-19 became clearer, overprotection during surgery and the simplification of certain techniques were reversed. Unnecessary in-ward isolation and examinations were also alleviated.

BRIEF SUMMARY OF CHINESE SURGEONS’ EXPERIENCE AND LESSON

Confirmed COVID-19 patients must be admitted to a predesignated hospital. In regular hospitals, suspected COVID-19 patients are thoroughly screened before proceeding to surgery. A screening model combining a thorough epidemiologic investigation, routine blood testing and C-reactive protein testing, and a chest CT was effective in identifying potential infections. Despite the global pandemic, no extra protection is needed during surgery as long as suspected COVID-19 patients are screened in advance.

Footnotes

Funding Support: None reported.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Portions of this content were presented during the Leadership During COVID-19 Advances in Surgery Channel Online Congress, April 9, 2020.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. 2020; Accessed May 4, 2020. www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- 2.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020; 395:470–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazzerini M, Putoto G. COVID-19 in Italy: momentous decisions and many uncertainties. Lancet Glob Health. 2020; 8:e641–e642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beijing Municipal Health Commission. 2020; Accessed May 4, 2020. wjw.beijing.gov.cn/wjwh/ztzl/xxgzbd/

- 5.National Health Committee of the People’s Republic of China. The guidance of diagnosis and treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Accessed May 4, 2020. www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3577/202002/573340613ab243b3a7f61df260551dd4.shtml