Abstract

Surgical treatment of malignant bone tumors comprises tumor resection and reconstruction. The most commonly used reconstruction method is prosthesis replacement, which achieves good early function, but has a high long-term incidence of complications. Another reconstruction option is autologous bone replantation, which has the advantages of anatomical matching and no need for large bone bank support. Few studies have evaluated reconstruction with liquid nitrogen-inactivated autogenous bone.

The present study aimed to evaluate the oncological results, bone healing results, complications, and indications of reconstruction with liquid nitrogen-inactivated autogenous bone grafts.

The study population comprised 21 consecutive patients. The tumor site was the tibia in 9 cases, femur in 8, and humerus in 4. There were 37 osteotomy ends in total. After freezing and rewarming, the medullary cavity of the autogenous bone was filled with antibiotic bone cement. Seventeen patients received bilateral plate fixation, 2 received intramedullary nail and distal plate fixation, and 2 received single plate fixation.

The average follow-up was 31 ± 6 months. Eighteen patients survived without tumors, and the 3-year survival rate was 80.4%. All cases had adequate surgical margins, but recurrence developed in 1 patient. Metastasis occurred in 3 patients, who all died of metastasis. Intraoperative inactivated bone fracture occurred in 1 patient, and screw breakage was found in 1 patient. Nonunion occurred at 1 humeral diaphysis osteotomy site, and 1 patient was lost to follow-up; the average healing time of the other 35 ends was 13 ± 6 months, and the bone healing rate was 97.2%. The average bone healing times in the metaphysis and diaphysis were 9 ± 3 months and 15 ± 6 months (P = .003). The average bone healing times in the upper and lower limbs were 16.6 ± 7.4 months and 12.3 ± 5.8 months (P = .020). The average Muscle and Skeletal Tumor Society score was 28 ± 3 (21–30) in the 18 survivors.

Liquid nitrogen-inactivated autologous bone replantation for primary malignant limb tumor was safe and effective, as shown by the relatively low complication rate, high bone healing rate, and satisfactory postoperative function. This is a reliable biological reconstruction method for malignant bone tumors with specific site and bone destruction characteristics.

Keywords: bone healing, liquid nitrogen inactivation, malignant bone tumors, oncological result, reconstruction

1. Introduction

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumor, with an incidence of approximately 2 to 3/million/yr.[1,2] The incidence of osteosarcoma is higher in adolescents than older adults (approximately 75% of patients with osteosarcoma are 15–25 years old), and the ratio of male to female patients is about 1.4 to 1.[1,2] Other common types of primary malignant bone tumor include Ewing sarcoma and chondrosarcoma. Malignant bone tumors often recur and metastasize, which seriously affects the quality of life and limb function of patients. With improvements in imaging, chemotherapy, and surgical techniques, most primary malignant tumors of the limbs can now be cured, and limb salvage surgery has become the preferred treatment.[2] Surgical treatment of primary malignant tumor of the limb comprises tumor resection and reconstruction. The application of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and appropriate surgical margins has reduced the local recurrence rate of primary limb malignant tumors after resection to 5% to 10%.[3,4] This low recurrence rate provides the possibility of limb salvage.

There are many reconstruction methods after tumor resection, such as artificial prosthesis replacement, allograft bone transplantation,[5] vascularized fibular transplantation,[6,7] arthroplasty, distraction osteogenesis,[8] and autologous bone inactivation and replantation.[9] At present, the most commonly used reconstruction method is artificial prosthesis replacement. Artificial prosthesis replacement achieves early function and good stability; however, the incidence of complications and the revision rate increase over time. In addition, revision is more difficult for a tumorous prosthesis than for a common joint prosthesis, and revision surgery for a tumorous prosthesis results in poor function and patient satisfaction. An alternative reconstruction method is autologous bone replantation, which has the advantages of anatomical matching, simple operational technique, relatively low cost, and no need for large bone bank support. Autologous bone replantation is a suitable reconstruction method in certain conditions.

Autologous bone inactivation is done via several methods, such as high temperature and pressure inactivation,[10] pasteurization,[11] external radiation,[12,13] absolute ethanol inactivation,[14] and liquid nitrogen inactivation.[9,15] In 2011, our department reported 191 cases of reconstruction performed using autologous bone inactivated with absolute alcohol.[14] The safety of these cases was the same as that of non-inactivated limb salvage performed in the same time period;14] however, after excluding tumor factors, the cases with alcohol-inactivated autologous bone implantation had a higher incidence of complications (inactivated bone fracture in 20.4%, infection in 20.4%, nonunion in 17.3%, and internal fixation failure in 7.9%), and the 5-year survival rate of inactivated bone was only 55%.[14] Therefore, liquid nitrogen inactivation was adopted in our department in 2015. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the oncological results, bone healing results, and complications of reconstruction with liquid nitrogen-inactivated autogenous bone grafts, and to determine the indications of this surgical procedure.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All cases included in the present study were identified from the database of our department. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Ji Shui Tan Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Inclusion criteria were: primary malignant bone and soft tissue tumors of the extremities; adequate surgical margins obtained by limb salvage surgery; cortical destruction in less than half of the normal bone on radiographic imaging; massive bone defect after tumor resection. Exclusion criteria were: pathological fracture at the tumor site before surgery; tumor progression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy; other concomitant tumors.

2.2. Clinical characteristics

In accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the present study included 21 consecutive patients who were treated between December 2015 and June 2017 (Table 1). There were 12 male and 9 female patients with a mean age of 24 ± 13 (8–55) years. A malignant pathological diagnosis was confirmed in all patients. There were 8 patients with classical osteosarcoma, 5 with Ewing sarcoma, 2 with highly malignant surface osteosarcoma, 2 with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of soft tissue, 1 with small cell osteosarcoma, 1 with low-grade central osteosarcoma, 1 with periosteal osteosarcoma, and 1 with chondrosarcoma. The tumor site was the tibia in 9 cases, the femur in 8 cases, and the humerus in 4 cases. Reconstruction methods were classified into the following categories in accordance with the reconstruction site: intercalary in 16 cases (76.2%), osteo-articular graft in 3 (14.3%), composite graft with prosthesis in 1 (4.8%), and segmental reconstruction of the diaphysis in 1 (4.8%).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients received reconstruction of frozen autologous bone inactivated with liquid nitrogen.

There were 37 osteotomy ends in total, comprising 2 osteotomy ends in the same long bone in 16 cases, and 1 osteotomy end in the same long bone in 5 cases. Twenty-six osteotomy ends were located in the diaphysis, while osteotomy ends were located in the metaphysis. Images obtained via radiography (DRX-Evolution Plus, Carestream Health) and computed tomography (CT) (Aquiline ONE, Toshiba) showed that 12 cases with osteogenic destruction had no cortical defect, 8 cases had a cortical defect of less than 1/3, and 1 case had a cortical defect of 50%.

2.3. Operative methods

2.3.1. Tumor resection

All procedures were performed in our department and all of the surgical plans were discussed by the members of our department. The tumor extent was determined preoperatively using contrast-enhanced CT and magnetic resonance imaging (Ingenia 3.0 T, Philips). The osteotomy position was designed to be 2 cm away from the tumor boundary to obtain adequate surgical margins. The operations were performed with different surgeons in charge, but the operation plans were formulated uniformly. In accordance with the principle of non-tumor operation, the bone was separated and exposed outside the reaction area before the bone was cut with a wire saw at the osteotomy site. A small amount of tissue from the broken end of the medullary cavity was collected for pathological examination to determine whether adequate surgical margins had been obtained.

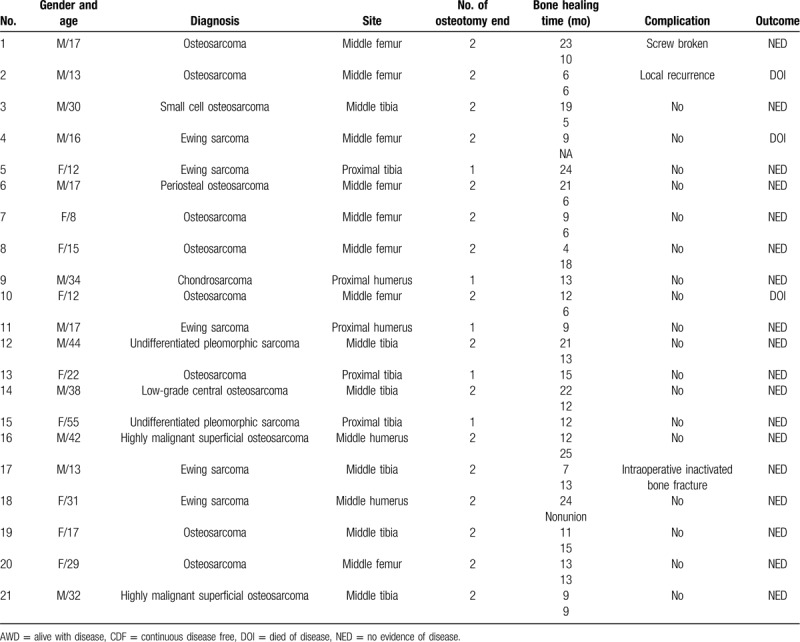

2.3.2. Inactivation with liquid nitrogen

The tumor soft tissue masses and muscles were removed to expose the cortical bone. The intramedullary tumors were removed from the osteotomy end, and only cortical bone was retained in the segment of the diaphysis (Fig. 1). In cases where the tumor involved the metaphysis, small bone windows were opened at the osteotomy end or laterally; tumor tissue was then removed, while normal cancellous bone was preserved. Some of the high-density tumor bone was able to be preserved in cases with an osteogenic lesion. If the shape of the cortex was abnormal and affected the internal fixation during reconstruction, it was repaired to near normal shape. Perforations were made along the long axis of the cortex with a 4-mm-diameter Stern's needle at intervals of 2 cm. The perforations were not made in the same plane. The abovementioned procedures were performed to prevent fracture during freezing.

Figure 1.

The preoperative radiography (A) and magnetic resonance imaging (B) of a 30 years male with small cell osteosarcoma of tibia diaphysis. The tumor was cut by wire saw at the osteotomy site (C). The tumor soft tissue masses and muscles were removed to expose cortical bone (D). The intramedullary tumors were removed from the osteotomy end. The autogenously bone was inactivated in liquid nitrogen for 20 minutes (E). The inactivated bone was fixed with bilateral plates (F–H).

The treated autogenous bone was washed with physiological saline and then frozen in liquid nitrogen for 20 minutes (Fig. 1). The autogenous bone was completely covered by liquid nitrogen. After 20 minutes, the bone was removed from the liquid nitrogen, rewarmed at room temperature for 15 minutes, and then rewarmed in saline for 15 minutes.

The medullary cavity was filled with antibiotic bone cement (Figs. 1 and 2). The portion of the cavity 0.5 cm from the osteotomy end was not filled with bone cement; this ensured that the inactivated bone segment was in full contact with the host bone after reconstruction.

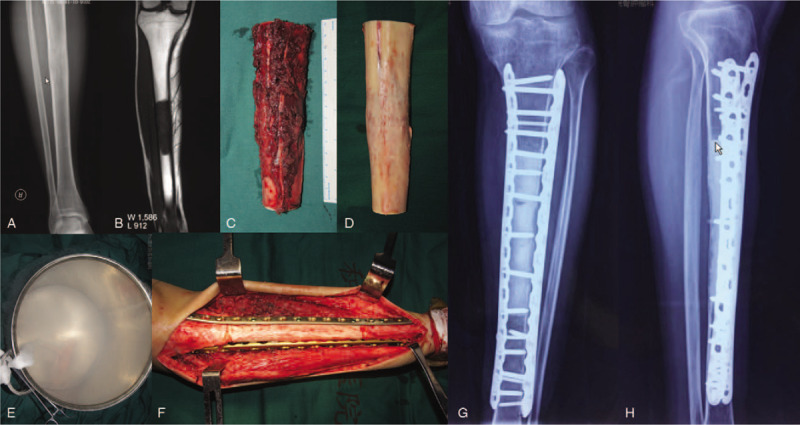

Figure 2.

The preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (A) of a 22 years female with osteosarcoma of proximal tibia. The tumor involved proximal tibia was wide excised (B). The follow-up of 29 months postoperative showed bone healing and good function result (C–E).

2.3.3. Reconstruction

Eighteen patients received bilateral plate fixation, and the plates were fixed with 4 screws at the host bone (Figs. 1 and 2). The osteotomy ends were located near the metaphysis in 3 patients; therefore, the length of plate at the host bone was insufficient to enable 4-screw fixation, and additional screw fixation outside the plane was used. A posterior cancellous bone fracture occurred in the course of tumor inactivation in a patient with a tibial tumor involving the metaphysis, and an additional plate was applied to fix the fracture. Two inactivated middle femurs were fixed with intramedullary nailing and distal plating because of insufficient plate length. Single plate fixation was used in 2 cases; 1 patient underwent mid-humeral resection, while the other underwent partial tibial resection.

2.4. Postoperative management

The postoperative drainage was removed when the drainage volume was less than 50 mL per day. Muscle isometric contraction of the affected limb was performed in the early postoperative period, and joint exercise was started at 2 weeks postoperatively. Partial weight-bearing was started at 6 weeks postoperatively. Radiographic examinations were performed every 3 months postoperatively. Full weight-bearing was commenced after the bone had healed.

2.5. Follow-up and evaluation

Perioperative complications and postoperative limb function were recorded. Outpatient follow-up was conducted every 3 months for 3 years, and then every 6 months for another 3 years. Imaging examinations included anterior-posterior and lateral radiography to evaluate the healing of the osteotomy ends. If radiography was unable to clearly display the osteotomy ends, CT was performed. Local ultrasonography was used to detect the recurrence of soft tissue and lymph node metastasis. Chest and whole-body CT were performed to evaluate distal metastasis. Functional assessment was performed using the Muscle and Skeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) scoring system.

The study endpoints were: removal of inactivated bone or amputation due to infection, recurrence, or other causes; patient death due to tumor recurrence, metastasis, or other causes.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 statistical software (SPSS Corporation, IBM Copr., Armonk, NY). Categorical variables were described by frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were described by mean, range, and median. Kaplan-Meier curves and the Log-rank test were used to analyze the survival rate and bone healing rate. The Chi-squared test and Fisher exact test were used to detect the relationship between bone healing time and tumor location. Two-sided P values of < .05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. General results

Surgery was successfully completed in all 21 patients. The average operation time was 372 ± 70 minutes (range 225–525 minutes; median 375 minutes). The average intraoperative bleeding volume was 683 ± 414 mL (range 200–2,000 mL; median 600 mL). The average follow-up time was 31 ± 6 months (range 19–43 months; median 30 months). The average length of the bone graft was 17.8 cm (range 10.0–30.0 cm; median 17.0 cm).

3.2. Oncological results

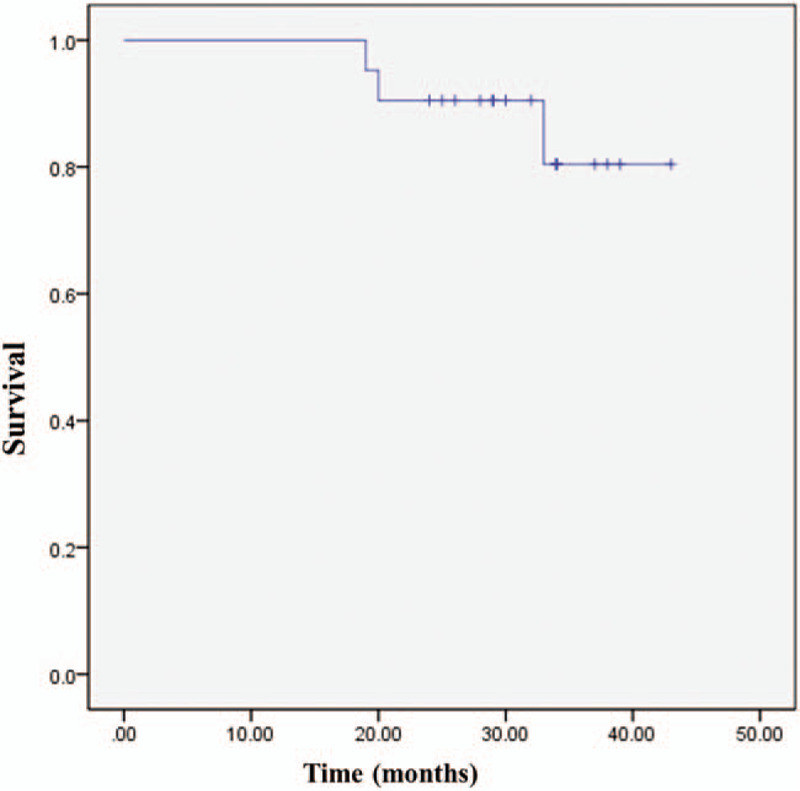

During the follow-up period, 18 patients survived without tumors, while 3 patients died. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that the 3-year survival rate was 80.4% (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The overall survival curve of the patients. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that the 3-year survival rate was 80.4%.

Postoperative pathological evaluation showed that all cases had adequate surgical margins; however, 1 patient still developed recurrence of femoral classical osteosarcoma. The patient with recurrence had previously undergone an incisional biopsy in a local hospital. Soft tissue recurrence was found 9 months postoperatively. The recurrent lesion was resected, and no tumor recurrence was found in the inactivated bone. At 15 months after the second operation, there was further soft tissue recurrence and multiple lung and brain metastases. The recurrence was resected again, and no recurrence was detected in the inactivated bone. The patient died 19 months after the first operation.

Metastasis occurred in 3 patients. One of these patients had recurrence as described above. One patient with classical osteosarcoma was found to have lung metastasis 18 months postoperatively and died at 33 months postoperatively. One patient with Ewing sarcoma of the femur was found to have multiple metastases of the lymph nodes, ribs, and lungs at 9 months postoperatively; this patient received systemic therapy in another hospital and died at 20 months postoperatively.

Three patients died of metastasis as described above; they survived for 19 months, 20 months, and 33 months postoperatively, respectively.

3.3. Complications

Intraoperative inactivated bone fracture (incomplete fracture with local fissure) occurred in 1 patient. This was treated via plate fixation, and the bone was healed at 7 months postoperatively. Examination revealed good function at the last follow-up performed at 26 months postoperatively.

No patients developed infection and delayed wound healing, rejection reaction, or postoperative inactivated bone fracture.

Failure of internal fixation occurred in a patient with classical osteosarcoma of the femur who received bilateral plate fixation in the initial operation. The osteotomy end in the metaphysis was healed at 10 months postoperatively. However, nonunion remained at the osteotomy end in the diaphysis at 17 months postoperatively, and 2 of the 7 fixation screws in the host bone were broken. There was no obvious displacement of the inactivated bone. The 2 broken screws were removed, and titanium cable fixation with autogenous iliac cancellous bone grafting was performed. The bone was healed at 23 months after the initial operation.

3.4. Bone healing results

Radiography or CT was used to evaluate the healing of the osteotomy ends for 36 of the 37 osteotomy ends (Fig. 2). One patient with Ewing sarcoma of the femur was only followed up for 9 months postoperatively. The proximal osteotomy end had healed, but the distal end had not. The patient then underwent further treatment for multiple metastases at other hospitals, and the distal osteotomy end was lost to follow-up. Among the remaining 36 osteotomy sites, nonunion remained at 1 humeral diaphysis osteotomy site at 28 months postoperatively. The other 35 ends were healed after an average time of 13 ± 6 months (range 4–25 months; median 12 months), and the bone healing rate was 97.2%. The self-healing rate was 94.4% (34/36); 1 patient with internal fixation failure underwent autografting and re-fixation.

The average bone healing times for the metaphysis and diaphysis were 9 ± 3 (4–13) months and 15 ± 6 (5–25) months, respectively. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) analysis showed that the bone healing time significantly differed between the metaphysis and diaphysis (x2 = 9.092, P = .003). The average bone healing times for the upper limb and lower limb were 16.6 ± 7.4 (9–25) months and 12.3 ± 5.8 (4–24) months. Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) analysis showed that the bone healing time significantly differed between the upper and lower limbs (x2 = 5.453, P = .020). The average healing time was 11.32 ± 6.165 (4–24) months in the patients younger than 18 years, and 14.81 ± 5.75 (5–25) months in the patients older than 18 years (P = .094, F = 2.969).

3.5. Function evaluation

The postoperative MSTS score was calculated at the last follow-up. In the 18 survivors, the average MSTS score was 28 ± 3 (21–30) and the average gait score was 4 (3–5). Nine patients had normal gait, while 9 had minor gait abnormalities.

4. Discussion

The most widely applied surgical treatment for malignant bone tumor is artificial prosthesis replacement. However, the long-term outcome of prosthesis replacement is poorer than that of reconstruction with biological material due to prosthesis loosening and other mechanical failures. The advantages of inactivated bone replantation are that the shape of the bone defect is consistent with that of the reconstruction material, and that the reconstruction is convenient. The rate of rejection for autograft bone is low compared with that for allograft bone.[14,15] Inactivated bone replantation is a good option for bone defect reconstruction in cases with diaphyseal tumors in which the joint can be retained after resection, or cases in which the tumor is too long to enable the retention of sufficient residual bone length for the implantation of a prosthesis stem.

In 2005, Tsuchiya et al[15] reported good results after reconstruction with liquid nitrogen-inactivated autologous bone after tumor resection. Liquid nitrogen inactivation technology in the reconstruction of bone defect after malignant bone tumor resection has been used in our institution since 2015. In the present study, the local recurrence rate was 5% (1/21), which was significantly lower than the recurrence rate of absolute alcohol-inactivated replantation (26.7%, 51/191) in our hospital.[14] This may be because alcohol inactivation only inactivates the thin lateral cortex and medullary cortex, while the deep tumor cells generally die within 4 days;[16] subsequent internal fixation destroys the surface of inactivated bone and nourishes the neovascularization of deep undead tumor cells, potentially resulting in tumor recurrence.

The oncological result (low recurrence rate) achieved with liquid nitrogen inactivation in our current study was similar to that reported after segmental resection and artificial joint reconstruction for malignant tumors of the extremities.[3] In the process of liquid nitrogen inactivation, the temperature in the medullary cavity drops steadily to below -150°C at 15 minutes after the implantation of the whole tumor in liquid nitrogen, which ensures the death of all tumor cells in the inactivated bone.[17] Thus, tumor recurrence does not occur, even after screw insertion during reconstruction. There was only 1 case of recurrence in the present study; the recurrence was found in the surrounding soft tissue, but not the inactivated bone in the second operation. Similarly, a recent study also found recurrence that originated from soft tissue rather than inactivated bone.[13] The present results indicate that liquid nitrogen inactivation of local tumors was oncological safe for primary malignant bone tumors. The metastasis rate was 14.3% (3/21) and the 3-year survival rate was 80.4%. This satisfactory result was mainly due to the standard treatment regimen comprising neoadjuvant and postoperative chemotherapy.

Inactivated bone healing refers to the healing of the join between the inactivated bone and the host bone. As the inactivation process kills all of the cells in the inactivated bone, these cells do not possess the ability of bone metabolism. Thus, inactivated bone healing takes a long time and carries a high probability of nonunion. This process is similar to the healing process of massive bone allografts. One study reported a rate of nonunion for replantation after inactivation by absolute alcohol of 17.3% (33/191),[14] while another study reported that 38 of 164 (23.8%) patients with massive bone allografts did not heal spontaneously.[18] In the current study, 34 of 36 (94.4%) osteotomy ends showed self-healing, and the healing rate was significantly higher than that of allograft and alcohol-inactivated bone. The healing rate of the present study was similar to that reported in a previous study of liquid nitrogen-inactivated bone healing (92.8%).[19]

The present study revealed that the healing of the diaphysis was slower than that of the metaphysis, as the revascularization of the metaphysis was faster than that of the diaphysis. In addition, the healing in the upper limb was slower than that in lower limb in the present study, which is similar to the findings of a previous study.[19] Increasing levels of appropriate stress may be beneficial for bone healing. Although the average healing time in the older patients in the present study was approximately 3.5 months longer than that in the younger patients, this difference was not statistically significant. This lack of significance may be due to the relatively small number of cases. There was a relatively small difference in resection length between cases in the present study, and so the influence of the graft length on bone healing time cannot be analyzed. However, bone union usually occurred at the 2 ends of the frozen bone, which suggests that the graft length would have had a limited influence on the time taken for bone union. Surgical intervention can be performed again in cases with nonunion between the inactivated bone and host bone. In the present study, 1 patient with femoral replantation showed nonunion in the diaphysis and screw breakage; this patient achieved good healing after autogenous cancellous bone grafting and re-screw wire fixation. In the study of massive allogenic bone grafts, some authors have defined nonunion as no sign of healing at 1 year postoperatively.[20,21] However, 44.4% (16/36) of the patients in the present study took more than 1 year postoperatively to heal, and 1 patient (3%) even healed at 25 months postoperatively. Thus, we believe that the inactivated bone will eventually heal, as long as the internal fixation does not fail. Lee et al[11] reported that 51 of 377 (13%) pasteurized osteotomy ends showed delayed union at 2 years postoperatively (average 40 months postoperatively). Therefore, the intervention strategy for nonunion in the present study was dependent on whether the internal fixation was ineffective and the osteotomy end was obviously absorbed, rather than being dependent on the time after surgery. Nonunion treatment options include local iliac bone grafting and vascularized fibular implantation.

The most common complication of inactivated bone replantation is graft fracture. Postoperative fracture has been reported in 2 of 18 (11.1%) patients who received an autograft inactivated by liquid nitrogen,[22] 2 of 22 (11%) patients after frozen autograft-prosthesis composite reconstruction,[23] and 7 of 36 (19.4%) patients who received an autograft inactivated by liquid nitrogen;[9] furthermore, fracture occurred after reconstruction for resection of malignant bone tumor in 3 of 5 (60%) patients in whom the epiphysis was reserved.[22] The graft fracture rate in the present study was lower than that reported with other techniques. We think that there were several main reasons for the relatively low graft fracture rate in the present study. The first reason was that the strength of inactivated bone is equivalent to that of intact bone. Bone strength is related to the form of bone destruction, and is decreased by osteolytic destruction. Miwa et al[24] reported that 18.2% of patients with frozen autografts experienced inactivated bone fracture during follow-up. In contrast, the fracture rates of sclerotic or mixed lesions are relatively low, ranging from 7.1% to 9.1%.[15,25] The present study only included cases with cortical destruction of less than 50% or osteogenesis. The second reason was the application of bone cement in the medullary cavity during the reconstruction process (only 3 of the present patients did not receive bone cement implantation), which is different to the previously reported techniques used in liquid nitrogen-inactivated replantation. We not only curetted the tumor tissue in the medullary cavity, but cleared the medullary cavity completely and then filled the whole medullary cavity with bone cement, except for the portion 0.5 cm from the osteotomy end. This cement filling procedure markedly improves the strength of reconstruction. Although the cement decreases the intramedullary blood flow, the bone union occurs at the 2 ends of the inactivated bone, and so the inactivated bone does not need an intramedullary blood supply for bone union. The third reason was the fixation method. In the present study, plate fixation was preferred to intramedullary nail fixation, as suggested in previous studies.[26,9] The fourth reason was the use of bilateral plates in reconstruction to increase the degree of support, especially in weight-bearing bones. If the condition did not permit the application of bilateral plates, plate fixation plus intramedullary nail fixation was performed. The fifth reason was that the patients did not perform full weight-bearing until complete healing had been achieved.

Delayed wound healing and infection are common complications after bone defect reconstruction, with a reported incidence of 5% to 11%.[9,13,23] However, there was no delayed wound healing or infection and no rejection in the present study. The incidence of wound complications is reduced by the achievement of good soft tissue coverage. In patients with massive soft tissue defects or defects at special sites (especially the tibia), muscle turnover coverage or myocutaneous flap transfer should be performed.

In the present study, the average postoperative MSTS score was 28 in the 18 survivors at the last follow-up. The postoperative functional recovery was good, and the patients were satisfied with the outcome. The present functional results were better than those reported after prosthesis replacement performed in the same time period.[27] Some older patients in the present study also received frozen autologous bone reconstruction rather than prosthesis reconstruction; this method was mainly chosen because the tumors were located in the middle shaft of the bone (knee articulation could be preserved safely after tumor resection), and intercalary prostheses were considered more likely to result in mechanical complications or failure. The possible negative effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on the process of bone union needs further study.

The present study has some limitations. The number of patients was small, and the follow-up time was relatively short. The sample size was small because the cases were strictly selected in accordance with the eligibility criteria; however, satisfactory reconstruction results were achieved with minimal complications. Furthermore, the present study included a heterogeneous study sample, and the study method was clinical evaluation. The weakest aspect of the re-use of bone grafts was that pathological examination was not performed and the necrosis percentage was not calculated. Subsequently, the modality of postoperative chemotherapy cannot be managed in accordance with the percentage of necrosis in the resected specimen, which may result in risk of death secondary to inappropriate postoperative chemotherapy.

In summary, liquid nitrogen-inactivated autologous bone replantation for primary malignant limb tumor was safe and effective during an average follow-up of 30 months. The complication rate was relatively low, the healing rate of the osteotomy ends was high, and the postoperative function was satisfactory. Therefore, liquid nitrogen-inactivated autologous bone replantation is a reliable biological reconstruction method for some malignant bone tumors with specific site and bone destruction characteristics. Autologous grafts contain autologous proteins, growth factors, and cytokines, do not induce an immune response, and have the advantages of early bone healing and low risk of bone resorption compared with allografts. We will continue the follow-up of the present patients to evaluate the long-term efficacy of liquid nitrogen-inactivated autologous bone replantation.

Author contributions

Data curation: Yuan Li, Yongkun Yang, Zhen Huang, Huachao Shan.

Project administration: Xiaohui Niu.

Writing – original draft: Yuan Li.

Writing – review & editing: Yongkun Yang.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, MSTS = Muscle and Skeletal Tumor Society.

How to cite this article: Li Y, Yang Y, Huang Z, Shan H, Xu H, Niu X. Bone defect reconstruction with autologous bone inactivated with liquid nitrogen after resection of primary limb malignant tumors: an observational study. Medicine. 2020;99:24(e20442).

All authors of this original work have directly participated in its conception and authorship and have read and approved the final version submitted. The authors have read the submission guidelines and the paper conforms to these guidelines in all respects.

The contents of this manuscript have not been copyrighted or published previously and are not now under consideration for publication elsewhere. The contents of this manuscript will not be copyrighted, submitted, or published elsewhere, while acceptance by this journal is under consideration. There are no directly related manuscripts or abstracts, published or unpublished, by any authors of this paper. The references mentioned in the manuscript have been checked and are correct.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- [1].Bielack S, Carrle D, Casali PG, et al. ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Osteosarcoma: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2009;20: Suppl 4: 137–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Allison DC, Carney SC, Ahlmann ER, et al. A meta-analysis of osteosarcoma outcomes in the modern medical era. Sarcoma 2012;2012:704872.1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pala E, Trovarelli G, Calabro T, et al. Survival of modern knee tumor megaprostheses: failures, functional results, and a comparative statistical analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473:891–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bus MP, van de Sande MA, Fiocco M, et al. What are the long-term results of MUTARS(R) modular endoprostheses for reconstruction of tumor resection of the distal femur and proximal tibia? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017;475:708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bus MP, van de Sande MA, Taminiau AH, et al. Is there still a role for osteoarticular allograft reconstruction in musculoskeletal tumour surgery? A long-term follow-up study of 38 patients and systematic review of the literature. Bone Joint J 2017;99-B:522–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Manfrini M, Bindiganavile S, Say F, et al. Is there benefit to free over pedicled vascularized grafts in augmenting tibial intercalary allograft constructs? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017;475:1322–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Piccolo PP, Ben-Amotz O, Ashley B, et al. Ankle arthrodesis with free vascularized fibula autograft using saphenous vein grafts: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg 2018;142:806–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Matsubara H, Tsuchiya H. Treatment of bone tumor using external fixator. J Orthop Sci 2019;24:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Igarashi K, Yamamoto N, Shirai T, et al. The long-term outcome following the use of frozen autograft treated with liquid nitrogen in the management of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Bone Joint J 2014;96-B:555–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Asada N, Tsuchiya H, Kitaoka K, et al. Massive autoclaved allografts and autografts for limb salvage surgery. A 1-8 year follow-up of 23 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1997;68:392–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee SY, Jeon DG, Cho WH, et al. Are pasteurized autografts durable for eeconstructions after bone tumor resections? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018;476:1728–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Salunke AA, Shah J, Chauhan TS, et al. Reconstruction with biological methods following intercalary excision of femoral diaphyseal tumors. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2019;27:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wu PK, Chen CF, Chen CM, et al. Intraoperative extracorporeal irradiation and frozen treatment on tumor-bearing autografts show equivalent outcomes for biologic reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018;476:877–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ding Y, Niu XH, Liu WF, et al. Excision-alcoholization-replantation method in management of bone tumors. Chin J Orthop 2011;31:652–7. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tsuchiya H, Wan SL, Sakayama K, et al. Reconstruction using an autograft containing tumour treated by liquid nitrogen. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sung HW, Wang HM, Kuo DP, et al. EAR method: an alternative method of bone grafting following bone tumor resection (a preliminary report). Semin Surg Oncol 1986;2:90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yamamoto N, Tsuchiya H, Tomita K. Effects of liquid nitrogen treatment on the proliferation of osteosarcoma and the biomechanical properties of normal bone. J Orthop Sci 2003;8:374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Niu XH, Hao L, Zhang Q, et al. Massive allograft replacement in management of bone tumors. Chin J Surg 2007;45:677–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ikuta K, Nishida Y, Sugiura H, et al. Predictors of complications in heat-treated autograft reconstruction after intercalary resection for malignant musculoskeletal tumors of the extremity. J Surg Oncol 2018;117:1469–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sorger JI, Hornicek FJ, Zavatta M, et al. Allograft fractures revisited. Clin Orthop 2001;382:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Brigman BE, Hornicek FJ, Gebhardt MC, et al. Allografts about the knee in young patients with high-grade sarcoma. Clin Orthop 2004;421:232–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hamed Kassem Abdelaal A, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, et al. Epiphyseal sparing and reconstruction by frozen bone autograft after malignant bone tumor resection in children. Sarcoma 2015;2015:892141.1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Subhadrabandhu S, Takeuchi A, Yamamoto N, et al. Frozen autograft-prosthesis composite reconstruction in malignant bone tumors. Orthopedics 2015;38:e911–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Miwa S, Takeuchi A, Shirai T, et al. Outcomes and complications of reconstruction using tumor-bearing frozen autografts in patients with metastatic bone tumors. Anticancer Res 2014;34:5569–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tsuchiya H, Nishida H, Srisawat P, et al. Pedicle frozen autograft reconstruction in malignant bone tumors. J Orthop Sci 2010;15:340–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gupta S, Kafchinski LA, Gundle KR, et al. Intercalary allograft augmented with intramedullary cement and plate fixation is a reliable solution after resection of a diaphyseal tumour. Bone Joint J 2017;99-B:973–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Li Y, Sun Y, Shan HC, et al. Comparative analysis of early follow-up of biologic fixation and cemented stem fixation for femoral tumor prosthesis. Orthop Surg 2019;11:451–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]