Abstract

Background

The role of radiotherapy (RT) in anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) for local tumor control is critical as mortality is often secondary to complications of tumor volume rather than metastatic disease. Here we report the long-term outcomes of RT for ATC.

Methods

We identified 104 patients with histologically confirmed ATC presenting to our institution between 1984–2017 who received curative-intent or post-operative RT. Locoregional progression free survival (LPFS), overall survival (OS), and distant metastasis free survival (DMFS) were assessed.

Results

Median age was 63.5 years. Median follow-up was 5.9 months (IQR 2.7–17.0) for the entire cohort and 10.6 months (IQR 5.3–40.0) in surviving patients. Thirty-one (29.8%) patients had metastatic disease prior to the start of RT. Concurrent chemoradiation was administered in 99 (95.2%) patients and trimodal therapy in 53 (51.0%) patients. Systemic therapy included doxorubicin (73.7%), paclitaxel with or without pazopanib (24.3%), and other systemic agents (2.0%). One-year OS and LPFS were 34.4% and 74.4% respectively. On multivariate analysis, RT dose60 Gy was associated with improved LPFS (HR=0.135, p=0.001) and improved OS (HR=0.487, p=0.004), and trimodal therapy was associated with improved LPFS (HR=0.060, p=0.017). Most commonly observed acute Grade 3 adverse events (AE) included dermatitis (20%) and mucositis (13%), with no observed Grade 4 subacute or late AE’s.

Conclusions

Radiotherapy demonstrates a dose-dependent persistent LPFS and OS benefit in locally advanced ATC with an acceptable toxicity profile. Aggressive RT should be strongly considered in the treatment of ATC as part of a trimodal treatment approach.

Keywords: Anaplastic thyroid cancer, undifferentiated thyroid cancer, radiation, EBRT, trimodality, multimodality, chemotherapy, chemoradiation

Precis for Table of Contents:

Radiotherapy demonstrates a dose-dependent persistent LPFS and OS benefit in locally advanced ATC with an acceptable toxicity profile. Aggressive RT should be strongly considered in the treatment of ATC as part of a trimodal treatment approach.

INTRODUCTION

Anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) is an aggressive form of thyroid cancer associated with poor prognosis. Although ATC accounts for less than 2% of all thyroid malignancies, it comprises more than 50% of thyroid related mortalities.1–3 Many studies have reported median overall survival of 6 months or less with one-year survival rates at around 20%.3–5

The morbidity of ATC is often due to locoregional disease rather than distant metastasis, due to the numerous critical structures near the thyroid such as the esophagus and trachea. Invasion into these structures can result in asphyxiation from upper airway compression.6 Therefore, improving locoregional progression free survival (LPFS) is vital to enhancing overall survival (OS) among these patients. Given its poor prognosis, ATC is typically treated with a combination of surgery, systemic therapy, and radiation therapy.7,8 Doxorubicin has been considered the standard chemotherapeutic agent for advanced ATC;9,10 however, various other systemic agents are currently under investigation as combination or single-agent systemic therapy in conjunction with radiation and/or surgery.11–17

The high incidence of metastatic disease also contributes to the poor prognosis of ATC, with almost half of all ATC cases presenting with evidence of metastatic disease at initial diagnosis.6 The most common metastatic sites include the lung, bone, and brain.18

Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is the current standard radiation modality and has been shown to improve tumor coverage while simultaneously decreasing the dose to surrounding normal tissues.19–21 Surgical intervention alone in ATC patients often has limited benefit due to tumor invasion of nearby critical structures in the neck and poorly defined tumor borders.7 Despite these obstacles, surgical intervention has been shown to improve overall survival and locoregional progression free survival in combination with chemotherapy and radiotherapy in select patient populations.8,18 The addition of surgical resection to systemic therapy and radiation was associated with an improved overall survival of 22.1 vs 6.5 months in a recent retrospective study.18

The aim of this large retrospective study is to determine whether aggressive radiation in combination with surgery and systemic therapy results in improved outcomes in patients with a definitive diagnosis of ATC.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

This retrospective study was independently reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board. We identified 104 consecutive patients with pathologically confirmed anaplastic thyroid cancer diagnosed at our center from 1984–2017; patients with poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma were excluded. Inclusion criteria required ATC with accurate pathological confirmation and curative-intent or post-operative RT treatment. Patients were excluded from the study if they received palliative RT.

Patient data including demographics, disease characteristics, baseline prognostic factors, treatment, and response were extracted from the electronic medical records. Tumor size was assessed by radiographic measurements when possible; otherwise clinical assessment or measurement of pathological specimen obtained during surgery were used, respectively. Adverse events were graded according to CTCAE version 4.0.22

Treatment

Surgery

Surgical interventions included either partial or total thyroidectomy with or without bilateral neck dissection based on the surgeon’s discretion. Resection was defined as R1 if the tumor was within 1 mm of the resected margins as per pathology reports and R2 was defined as presence of gross residual disease. Patients were not included in the surgical group if the surgery was not completed or was aborted based on physician judgement.

Radiation Therapy

All patients underwent immobilization with a thermoplastic head-neck or, more recently, head–neck–shoulder mask, to ensure daily reproducibility of the radiotherapy fields. Prior to 2002, all patients (n=30) received radiation treatment twice a day, three times a week, to a total dose up to 57.60Gy (fraction size of 1.6Gy). Since then, all patients, except for 3 patients (n=71), received radiation treatment once a day, five times a week to a total dose up to 70.00Gy (fraction size of 1.8–2.2Gy).

Systemic Therapy

Patients were treated with varying types of systemic agents including doxorubicin, cisplatin, paclitaxel, docetaxel, and pazopanib. Doxorubicin doses included 10–20mg/m2, pazopanib 400mg oral suspension daily for two weeks, and paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 IV weekly for 2 weeks.

Outcome definitions

Follow-up was calculated from start of radiation until last recorded physician visit. LPFS was measured from start of radiotherapy until progression of locoregional disease based on increasing size of primary tumor and/or regional lymph nodes on imaging (or clinical exam if imaging was not available), and date of last follow up in the absence of locoregional progression. Distant metastasis (DM) was defined as any disease outside the cervical neck and upper mediastinum. OS was assessed from the date of surgery or start of radiotherapy, whichever occurred first, until death or last follow-up date. Patients without evidence of metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis were followed to determine the distant metastasis free survival (DMFS), scored by either radiographic evidence or histological evidence of progression.

Statistical Methods

We assessed OS, LPFS, and DMFS using the Kaplan-Meier method and performed survival analysis using Cox proportional hazard models. Univariate (UVA) and multivariate (MVA) analyses were performed. Any category with a p value less than 0.05 on UVA was included in the MVA. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact test, medians were compared using Mann-Whitney U test. Data were analyzed by using SAS® 9.4 software and IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software.

Gene Mutation Testing

Mutational status of select patients was obtained at physician discretion. All patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma whose tumors were sequenced with MSK-IMPACT at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, NY) were analyzed for established or suspected oncogenic alterations in TP53, TERT, BRAF, and PTEN.23–25

RESULTS

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

Table 1 details the characteristics of patient and tumor. The median age was 63.5 years (range 28–87 years) and 55/104 (52.9%) were female. The majority had IVB disease at diagnosis (73.1%), followed by IVC (22.1%). Only 5 patients (4.8%) presented with IVA disease. Approximately 94% of the patients had extrathyroidal extension, and sixty-nine patients (66.3%) had lymph nodes involvement. About 38% of the patients had coexistent differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Median tumor size was 6.5cm (range 2.0–17.8cm, available for 93.3% of patients). Thirteen patients (12.5%) required tracheostomy. There was no statistically significant difference in percentage of patients needing tracheostomy between surgically treated group and nonsurgical group (12.7% vs. 12.2%, p=0.941). Twenty-three patients (22.1%) had evidence of metastatic disease at diagnosis and all these patients were diagnosed after 2002. Thirty-one patients (29.8%) developed metastasis prior to start of radiotherapy.

Table 1.

Patient and treatment characteristics

| Baseline clinical and treatment characteristics (n=104) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 63.5 (28–87) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 49 (47.1) |

| Female | 55 (52.9) |

| Stage | |

| IV A | 5 (4.8) |

| IV B | 76 (73.1) |

| IV C | 23 (22.1) |

| Tumor size, median (range), cm | 6.5 (2.0–17.8) |

| Coexistent differentiated thyroid carcinoma | |

| Yes | 39 (37.5) |

| No | 65 (62.5) |

| Tracheostomy | |

| Yes | 13 (12.5) |

| No | 91 (87.5) |

| Extrathyroidal extension | |

| Yes | 98 (94.2) |

| No | 5 (4.8) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.0) |

| Gross tumor mass before radiotherapy | |

| Yes | 71 (68.3) |

| No | 33 (31.7) |

| Distant metastases | |

| At the time of diagnosis | 23 (22.1) |

| Before radiotherapy | 31 (29.8) |

| After treatment courses | 49 (47.1) |

| Surgery | |

| None | 49 (47.1) |

| R2 | 17 (16.3) |

| R1 | 22 (21.2) |

| R0 | 13 (12.5) |

| Unknown | 3 (2.9) |

| Radiotherapy | |

| Median dose (range), cGy | 6600 (600–7025) |

| Median fraction (range) | 33 (3–40) |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 99 (95.2) |

| No | 5 (4.8) |

| Concurrent chemotherapy regimens | |

| Doxorubicin based regimen | 73 (73.7) |

| Paclitaxel based regimen | 24 (24.3) |

| Others | 2 (2.0) |

| Trimodal therapy | |

| Yes | 53 (51.0) |

| No | 51 (49.0) |

Treatment Characteristics

Ninety-nine patients (95.2%) received concurrent chemotherapy with radiation, and 53 (51.0%) received trimodal therapy with surgical resection followed by concurrent chemoradiation. Of the patients receiving surgical intervention (n=55), 13 (12.5%) had a R0 resection, 22 (21.2%) had a R1 resection, and 17 (16.3%) had a R2 resection. Seventy-one patients (68.3%) had gross tumor mass prior to RT. Among these patients, 17 received R2 resection and four patients had R0 or R1 resection but rapidly developed thyroid mass again prior to the start of RT. Of the patients who received systemic therapy (n=99), 73 (73.7%) received doxorubicin, 24 (24.3%) received paclitaxel with or without pazopanib in a clinical trial setting, and 2 (2.0%) received other systemic agents. The median EBRT dose was 66.00 Gy (range 6.00–70.25 Gy) with a median of 33 fractions (range 3–40, Table 1). Seventy-four patients (71.2%) received IMRT, and the remainder received 3D conformal. Radiation was given either BID (31.7%) or daily (68.3%). Of the patients received EBRT less than 60.00Gy (n=46), 26 (56.5%) received more than 50.00Gy based on the old protocol prior to 2002, twenty patients could not complete the intended full dose due to progression of disease or deteriorating condition.

All patients with stage IVA disease (n=5) treated with trimodal therapy. Of the patients with IVB disease (n=76), 42 (55.3%) received trimodal therapy, 32 (42.1%) received concurrent chemoradiation, and 2 (2.6%) treated with RT alone due to age and medical comorbidities. Of the patients with stage IVC disease (n=23), 6 (26.1%) underwent trimodal treatment, 14(60.9%) received concurrent chemoradiation, and 3 (13.0%) treated with RT alone. Specifically, in those patients with stage IVC disease and who received surgical resection (n=6), 83% were diagnosed after 2010 and all six patients were treated after 2005. Tumor size ranged from 6.0cm to 8.0cm, and 5 patients (83.3%) post-operatively were diagnosed as ATC with coexisting differentiated component. Median OS of these six patients was 4.1 months versus 2.8 months for the remaining patients with IVC disease.

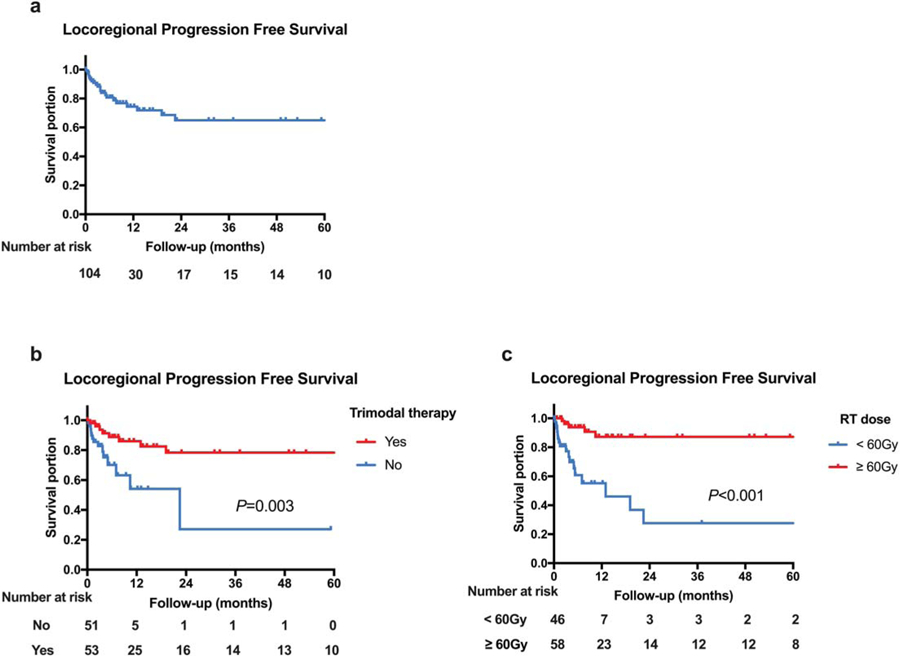

Locoregional Progression Free Survival

The 1-year LPFS rate was 74.4% (Fig. 1a). Twenty-two (21.2%) patients failed locally and 14 (13.5%) patients were alive at the conclusion of the study. There was a statistically significant difference in the 1-year LPFS between patients according to trimodal treatment (54.1% vs 85.9%, p=0.003, Fig. 1b) and RT dose <60 vs ≥60 Gy (55.3% vs 87.2%, p<0.001, Fig. 1c), which was also observed with a cut-off value of 50 Gy (62.9% vs 78.2%, p<0.001).

Figure 1. Locoregional Progression Free Survival:

(a) Locoregional progression free survival in all patients, (b) Comparative LPFS in patients by trimodal treatment, and (c) Comparative LPFS in patients by radiation dose of 60 Gy.

On univariate analysis, surgery (p=0.008), trimodal treatment (p=0.003), absence of gross tumor mass prior to RT (p=0.006), coexistent differentiated thyroid carcinoma (p=0.041), and a RT dose 60 Gy (p<0.001) were associated with a decreased risk of local progression. Only trimodal treatment (p=0.017) and RT dose60 Gy (p=0.001) was associated with decreased risk of local progression on multivariate analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of locoregional progression free survival (LPFS) and overall survival (OS)

| Locoregional Progression Free Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | UVA p value | MVA p value | MVA HR [95% CI] |

| Trimodal therapy | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.003 | 0.017 | 0.060 [0.006–0.611] |

| Surgery | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.008 | 0.067 | 11.103 [0.848–145.376] |

| RT dose | |||

| ≥60 | 1 | ||

| < 60 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.135 [0.042–0.430] |

| Gross tumor mass before RT | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.006 | 0.192 | 2.430 [0.640–9.219] |

| Coexistent differentiated tdyroid carcinoma | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.041 | 0.765 | 1.225 [0.323–4.649] |

| Age (70 years cut-off) | NS | ||

| Gender | NS | ||

| Extratdyroidal extension | NS | ||

| Stage | NS | ||

| Tumor size (6.5cm cut-off) | NS | ||

| Concurrent chemotderapy | NS | ||

| Concurrent chemotderapy regimens | NS | ||

| Tracheostomy | NS | ||

| Distant metastases before RT | NS | ||

| Overall Survival | |||

| Characteristics | UVA p value | MVA p value | MVA HR [95% CI] |

| Age | |||

| <70 | 1 | ||

| ≥70 | <0.001 | 0.281 | 1.370 [0.773–2.427] |

| Extrathyroidal extension | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.003 | 0.200 | 4.491 [0.452–44.611] |

| Trimodal therapy | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 0.649 | 1.628 [0.200–13.277] |

| Stage | |||

| IV A | 1 | ||

| IV B | |||

| IV C | <0.001 | 0.438 | 1.522 [0.527–4.393] |

| Surgery | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 0.269 | 0.278 [0.029–2.687] |

| Gross tumor mass before RT | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 0.688 | 0.868 [0.436–1.729] |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.026 | 0.382 | 0.567 [0.159–2.022] |

| RT dose | |||

| ≥60 | 1 | ||

| <60 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.487 [0.300–0.791] |

| Distant metastases before RT | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 0.009 | 3.430 [1.360–8.652] |

| Coexistent differentiated thyroid carcinoma | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 0.307 | 0.713 [0.372–1.365] |

| Gender | NS | ||

| Tumor size (6.5cm cut-off) | NS | ||

| Concurrent chemotherapy regimens | NS | ||

| Tracheostomy | NS | ||

Abbreviations: RT, radiotherapy; UVA, univariate analysis; MVA, multivariate analysis; NS, non-significant.

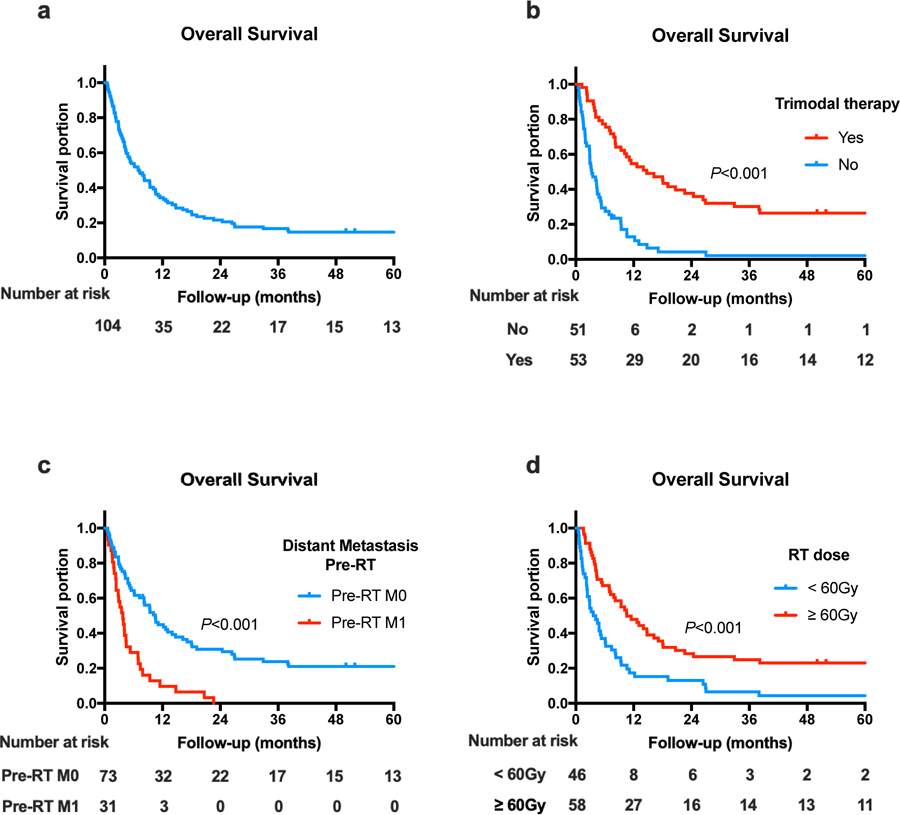

Overall survival

For the entire cohort, the median OS was 7.0 months (95% CI 4.5–9.5) with 34.4% survival at 1 year (Fig. 2a). Median follow-up was 5.9 months (IQR 2.7–17.0) for the entire cohort and 10.6 months (IQR 5.3–40.0) in surviving patients. Ninety (86.5%) patients died at the time of last follow up; fifteen (16.7%) of the 90 patients had both local and distant disease, 60 (66.7%) had distant metastasis alone at the time of death and 7 (7.8%) patients died with local tumor progression alone. There were statistically significant differences in the 1-year OS according to trimodal treatment (12.8% vs 54.7%, p<0.001, Fig. 2b), distant metastases prior to RT (44.9% vs 9.7%, p<0.001, Fig. 2c) and RT dose, <60 vs ≥60 Gy (17.4% vs 47.9%, p<0.001, Fig. 2d) which also held up with a cut-off value of 50 Gy (5.0% vs 41.3%, p<0.001). Median OS for patients receiving ≥60 Gy was 10.6 months compared with 3.6 months among patients receiving <60 Gy.

Figure 2. Overall Survival:

(a) Overall survival in all patients, (b) Comparative OS in patients by trimodal treatment, (c) Comparative OS in patients by presence of distant metastasis prior to RT, and (d) Comparative OS in patients by radiation dose of 60 Gy.

Improved overall survival was associated with age <70 years (p<0.001), absence of extrathyroidal extension (p=0.003), surgery (p<0.001), concurrent chemotherapy (p=0.026), trimodal treatment (p<0.001), early stage (p<0.001), absence of gross tumor mass before RT (p<0.001), coexistent differentiated thyroid carcinoma (p<0.001), absence of metastases before RT (p<0.001) and RT dose 60 Gy (p<0.001) on univariate analysis, but only absence of metastases before RT (p=0.009) and RT dose 60 (p=0.004) remained statistically significant on multivariate analysis (Table 2).

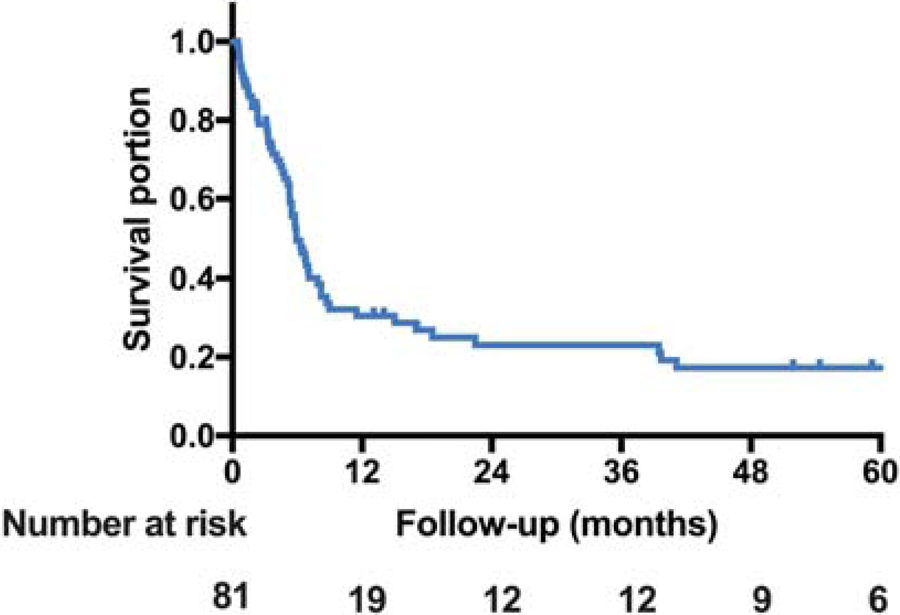

Distant Metastasis Free Survival

Of the 81 patients without distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, 56 patients (69.1%) subsequently developed metastases at a median 5.9 months (95%CI 4.5–7.3) with a 1-year distant metastasis rate of 30.5% (Fig. 3). Of the 6 patients with more than 60 months DMFS, 2 patients had pure ATC and remaining 4 patients had coexistent differentiated thyroid cancer. There were 2 patients with stage IVA disease, 4 with stage IVB disease. Median tumor size was 6.0cm, ranging from 3.0cm to 8.0cm, and only one patient had lymph node involvement. All the 6 patients received trimodal therapy and was without evidence of disease afterwards.

Figure 3. Distant Metastasis Free Survival:

Distant metastasis free survival in patients without evidence of metastatic disease at diagnosis (n=81).

Toxicities

The most commonly observed acute Grade 3 adverse events include dermatitis (20%), mucositis (13%), dysphagia (8%), and fatigue (7%). There were 3 cases of subacute Grade 3 fatigue, 4 cases of late Grade 3 fatigue and 1 case of Grade 3 mucositis. There were no Grade 4 subacute or late AE’s (Table 3).

Table 3.

Toxicities

| Baseline | Acute 0–3 months | Subacute 3–6 months | Late 3–6 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTAE Grade | 1–2 | 3–4 | 1–2 | 3–4 | 1–2 | 3–4 | 1–2 | 3–4 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| General | ||||||||

| Fatigue | 5 (5%) | 74 (71%) | 8 (8%) | 26 (25%) | 3 (3%) | 31 (30%) | 4 (4%) | |

| Nausea | 3 (3%) | 58 (56%) | 1 (1%) | 10 (10%) | 12 (12%) | |||

| Vomiting | 1 (1%) | 33 (32%) | 1 (1%) | 8 (8%) | 8 (8%) | |||

| Skin | ||||||||

| Dermatitis | 1 (1%) | 40 (38%) | 21 (20%) | 13 (13%) | 15 (14%) | |||

| Head/Neck | ||||||||

| Mucositis | 1 (1%) | 52 (50%) | 13 (13%) | 14 (13%) | 12 (12%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Xerostomia | 1 (1%) | 52 (50%) | 11 (11%) | 12 (12%) | ||||

| Dysphagia | 4 (4%) | 66 (63%) | 8 (8%) | 19 (18%) | 20 (19%) | |||

| Voice changes | 2 (2%) | 49 (47%) | 2 (2%) | |||||

| Taste | 1 (1%) | 48 (46%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | ||||

Mutational Status

32 patients (31%) underwent mutation testing at physician discretion with 24 patients (75%) testing positive for at least one of the following genes: TP53 (50% of sequenced patients), TERT (47%), BRAF (38%), and PTEN (19%). After receiving prior multimodal therapy, 6 patients with BRAF mutation received systemic therapy based on molecular profiling consisting vemurafenib and/or dabrafenib/trametinib combination. One patient was given everolimus based on PTEN mutational status. Median OS of this small population was 20.7 months (95% CI 14.2–27.2) versus 7.0 months (95% CI 4.5–9.5) for all patients.

DISCUSSION

Management of anaplastic thyroid cancer remains difficult due to the aggressive histology, the high rates of locoregional invasion, and the presence of distant metastasis.18,26 Both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and the American Thyroid Association (ATA) recommend multimodal therapy with upfront surgery when possible.1,27 Here we report on improved outcomes in ATC patients undergoing trimodal therapy consisting of surgical resection of the tumor, chemotherapy, and aggressive radiation therapy (≥60Gy).

A critical review of doxorubicin and radiotherapy in the treatment of ATC patients by Sherman et al. concluded that a median radiotherapy dose of 57.6 Gy and weekly doxorubicin 10 mg/m2 was associated with one-year outcomes for locoregional progression free survival at 45% and overall survival at 28%.7 These investigators reported local tumor control rates at two years of 68% and 49% respectively, and one-year survival rates at 50% and 30% respectively.

In this study, we conducted a large-scale institutional analysis of all ATC patients diagnosed over a 33-year period which expands upon earlier literature.7,28,29 Importantly, only patients with accurate pathological confirmation of ATC were included. Although ATC is often studied alongside poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma, the latter is associated with better outcomes than ATC.

Previous studies have indicated that surgical resection is associated with improved outcomes in ATC patients.8,18,30–32 Studies have demonstrated similar improvements in outcome with more aggressive chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgical resection.18,33 Initial intensive multimodal therapy appeared to be associated with improved survival even in late stage disease in an earlier retrospective study, with more aggressive radiation therapy (46–70Gy) associated with improved survival outcomes.32 The pattern of failure for these studies tended to be distant metastasis, which is consistent with our findings and suggests that aggressive local therapy with surgery and radiation provides adequate local control.

The importance of radiation is further demonstrated by a recent NCDB analysis of over 1,200 anaplastic thyroid cancer patients which found a positive radiation dose-survival correlation among the entire study cohort, Stage IV disease, and among patients receiving chemotherapy.34 The correlation for patients receiving 60–75 Gy versus 45–59.9 Gy was confirmed by propensity score matching and correlated with OS. Notably, one-year OS was only 11% in this study. These data support our findings that high-dose radiation is associated with improved outcomes in the context of multimodal therapy. However, the differences in median OS among the patients receiving ≥60 Gy was 10.6 months, compared with 3.6 months among patients receiving less than <60 Gy. This suggests that the difference in outcomes may be associated with patient comorbidity.

The frequency and mutations seen in our cohort is comparable to historical literature with regards to higher frequency of mutations in TP53, TERT, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway effectors.35 In our study, a longer median OS was observed in the small group of patients treated with systemic therapy based on molecular profiling. Further study of these mutations may lead to the development of more targeted therapies for selected patient populations.

However, as a retrospective study, our findings are subject to the effect of stage migration wherein improvements in diagnosis, workup, and imaging may lead to changes in diagnosis patterns.36 Selection bias is another possible limitation of the study among patients considered suitable for trimodal therapy.

Prognosis of anaplastic thyroid cancer remains poor despite aggressive multimodal therapy. There are numerous ongoing clinical trials investigating various combinations of targeted therapies and immunotherapies for ATC patients.11–17 Various radiation modalities and fractionation schedules are also being actively investigated.

In conclusion, this large-scale single-institution 33-year experience with anaplastic thyroid cancer identifies several factors associated with statistically significant improvements in LPFS and OS for RT dose60 Gy, improvements in LPFS for trimodal therapy, and improvements in OS for absence of metastatic disease prior to RT on multivariate analysis, suggesting that high doses of radiation can be effective in select patients. The current practice at this institution is 69.96 Gy in 33 fractions for gross disease and 59.40 Gy in 33 fractions for microscopic disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 and by the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology. Dr. Fan’s research was partly supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC No. 201706370238).

Footnotes

Disclaimers: The authors report no relevant financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smallridge RC, Ain KB, Asa SL, et al. American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2012;22(11):1104–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuffrida D, Gharib H. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: current diagnosis and treatment. Ann Oncol. 2000;11(9):1083–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taccaliti A, Silvetti F, Palmonella G, Boscaro M. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2012;3:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim SM, Shin SJ, Chung WY, et al. Treatment outcome of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer: a single center experience. Yonsei Med J. 2012;53(2):352–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kebebew E, Greenspan FS, Clark OH, Woeber KA, McMillan A. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Treatment outcome and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1330–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Are C, Shaha AR. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: biology, pathogenesis, prognostic factors, and treatment approaches. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(4):453–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherman EJ, Lim SH, Ho AL, et al. Concurrent doxorubicin and radiotherapy for anaplastic thyroid cancer: a critical re-evaluation including uniform pathologic review. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101(3):425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haigh PI, Ituarte PH, Wu HS, et al. Completely resected anaplastic thyroid carcinoma combined with adjuvant chemotherapy and irradiation is associated with prolonged survival. Cancer. 2001;91(12):2335–2342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JH, Leeper RD. Treatment of locally advanced thyroid carcinoma with combination doxorubicin and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1987;60(10):2372–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Leeper RD. Treatment of anaplastic giant and spindle cell carcinoma of the thyroid gland with combination Adriamycin and radiation therapy. A new approach. Cancer. 1983;52(6):954–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ClinicalTrials.gov Pembrolizumab, Chemotherapy, and Radiation Therapy With or Without Surgery in Treating Patients With Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03211117 Published July 7, 2017. Updated May 1, 2018 Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 12.ClinicalTrials.gov Atezolizumab Combinations With Chemotherapy for Anaplastic and Poorly Differentiated Thyroid Carcinomas. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03181100 Published June 8, 2017. Updated July 24, 2018 Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 13.ClinicalTrials.gov Pembrolizumab in Anaplastic/Undifferentiated Thyroid Cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02688608 Published February 23, 2016. Updated November 20, 2017 Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 14.ClinicalTrials.gov Inolitazone Dihydrochloride and Paclitaxel in Treating Patients With Advanced Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02152137 Published June 2, 2014. Updated September 6, 2018 Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 15.ClinicalTrials.gov A Phase 2 Trial of Lenvatinib for the Treatment of Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer (ATC). https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02657369 Published January 15, 2016. Updated November 7, 2017 Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 16.ClinicalTrials.gov A Phase II Study of MLN0128 in Metastatic Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02244463 Published September 19, 2014 Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 17.ClinicalTrials.gov Phase II Study Assessing the Efficacy and Safety of Lenvatinib for Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02726503 Published April 1, 2016. Updated June 2, 2017 Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 18.Rao SN, Zafereo M, Dadu R, et al. Patterns of Treatment Failure in Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma. Thyroid. 2017;27(5):672–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nutting CM, Convery DJ, Cosgrove VP, et al. Improvements in target coverage and reduced spinal cord irradiation using intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) in patients with carcinoma of the thyroid gland. Radiother Oncol. 2001;60(2):173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee N, Xia P, Fischbein NJ, Akazawa P, Akazawa C, Quivey JM. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head-and-neck cancer: the UCSF experience focusing on target volume delineation. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2003;57(1):49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posner MD, Quivey JM, Akazawa PF, Xia P, Akazawa C, Verhey LJ. Dose optimization for the treatment of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a comparison of treatment planning techniques. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(2):475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Services USDoHaH. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). In: NIH/NCI, ed. Version 4.03 ed2010.

- 23.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17(3):251–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data. Cancer Discovery. 2012;2(5):401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6(269):pl1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed S, Ghazarian MP, Cabanillas ME, et al. Imaging of Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(3):547–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Network NCC. NCCN Guidelines Thyroid Carcinoma -- Anaplastic Carcinoma (Version 1.2018). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thyroid.pdf Published 2018. Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 28.Brierley J, Sherman E. The role of external beam radiation and targeted therapy in thyroid cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2012;22(3):254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohebati A, Dilorenzo M, Palmer F, et al. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a 25-year single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1665–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yau T, Lo CY, Epstein RJ, Lam AK, Wan KY, Lang BH. Treatment outcomes in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: survival improvement in young patients with localized disease treated by combination of surgery and radiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2500–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Crevoisier R, Baudin E, Bachelot A, et al. Combined treatment of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma with surgery, chemotherapy, and hyperfractionated accelerated external radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(4):1137–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prasongsook N, Kumar A, Chintakuntlawar AV, et al. Survival in Response to Multimodal Therapy in Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(12):4506–4514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foote RL, Molina JR, Kasperbauer JL, et al. Enhanced survival in locoregionally confined anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a single-institution experience using aggressive multimodal therapy. Thyroid. 2011;21(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pezzi TA, Mohamed ASR, Sheu T, et al. Radiation therapy dose is associated with improved survival for unresected anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Outcomes from the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2017;123(9):1653–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landa I, Ibrahimpasic T, Boucai L, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic hallmarks of poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(3):1052–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(25):1604–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]