Abstract

SARM1 is the central executioner of pathological axon degeneration, promoting axonal demise in response to axotomy, traumatic brain injury, and neurotoxic chemotherapeutics that induce peripheral neuropathy. SARM1 is an injury-activated NAD+ cleavage enzyme, and this NADase activity is required for the pro-degenerative function of SARM1. At present, SARM1 function is assayed by either analysis of axonal loss, which is far downstream of SARM1 enzymatic activity, or via NAD+ levels, which are regulated by many competing pathways. Here we explored the utility of measuring cADPR, a product of SARM1-dependent cleavage of NAD+, as an in cell and in vivo biomarker of SARM1 enzymatic activity. We find that SARM1 is a major producer of cADPR in cultured dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, sciatic nerve, and brain, demonstrating that SARM1 has basal activity in the absence of injury. Following injury, there is a dramatic SARM1-dependent increase in the levels of axonal cADPR that precedes morphological axon degeneration. In vivo, there is also a rapid and large injury-stimulated increase in cADPR in sciatic and optic nerves. The increase in cADPR after injury is proportional to SARM1 gene dosage, suggesting that SARM1 activity is the prime regulator of cADPR levels. The role of cADPR as an important calcium mobilizing agent prompted exploration of its functional contribution to axon degeneration. We used multiple bacterial and mammalian engineered enzymes to manipulate cADPR levels in neurons but found no changes in the time course of axonal degeneration, suggesting that cADPR is unlikely to be an important contributor to the degenerative mechanism. Using cADPR as a SARM1 biomarker, we find that SARM1 can be partially activated by a diverse array of mitochondrial toxins administered at doses that do not induce axon degeneration. Hence, the subcritical activation of SARM1 induced by mitochondrial dysfunction may contribute to the axonal vulnerability common to many neurodegenerative diseases. Finally, we assay levels of both nerve cADPR and plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL) following nerve injury in vivo, and demonstrate that both biomarkers are excellent readouts of SARM1 activity, with cADPR reporting the early molecular changes in the nerve and NfL reporting subsequent axonal breakdown. The identification and characterization of cADPR as a SARM1 biomarker will help identify neurodegenerative diseases in which SARM1 contributes to axonal loss and expedite target validation studies of SARM1-directed therapeutics.

Introduction:

SARM1 is the central executioner of pathological axon degeneration, functioning downstream of disparate insults to trigger axonal self-destruction (DiAntonio, 2019). Loss of SARM1 provides dramatic protection in animal models of traumatic nerve injury (Gerdts et al., 2013; 2015; Osterloh et al., 2012), chemotherapy- and diabetes-induced peripheral neuropathy (Cheng et al., 2019; Geisler et al., 2016; Geisler, et al., 2019; Turkiew et al., 2017), and traumatic brain injury (Henninger et al., 2016; Marion et al., 2019; Ziogas and Koliatsos, 2018). Moreover, axon loss is a central component of many neurodegenerative disorders, and so there is great interest in the potential role of SARM1 in diseases such as ALS, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s Disease, and glaucoma. The therapeutic potential of targeting SARM1 has motivated detailed studies of its mechanism of action. We recently demonstrated that SARM1 is the founding member of a new class of NAD+ cleaving enzymes, that axon injury activates this SARM1 NADase activity, and that SARM1 NADase activity is required for axon degeneration (Essuman et al., 2017; Sasaki et al., 2016). The recognition that SARM1 is an enzyme creates opportunities both for the development of SARM1-directed therapeutics (Geisler, Huang, et al., 2019), and, as explored here, the development of a biomarker reporting SARM1 activity.

SARM1 is the founding member of the TIR domain family of NAD+ cleaving enzymes (Essuman et al., 2017). Others and we have demonstrated that TIR domain NADases exist in bacteria, archaea, and in plants (Essuman et al., 2018; Horsefield et al., 2019; Wan et al., 2019). These enzymes cleave NAD+ and related molecules such as NADP at the nicotinamide-ribosyl bond. In enzymatic studies in vitro, the SARM1 NADase cleaves NAD+ to generate nicotinamide and either ADPR (adenosine diphosphate ribose) or cyclic ADPR (cADPR), with ADPR as the predominant species (Essuman et al., 2017). In tissue culture cells, overexpression of SARM1 leads to the generation of cADPR (Zhao et al., 2019). In neurons, SARM1 activation leads to a decline in axonal NAD+ levels (Gerdts et al., 2015), however the generation of NAD+ cleavage products in neurons has yet to be assessed. Both ADPR and cADPR are potent calcium mobilizing metabolites (Guse, 2015), and calcium is an important trigger of axon degeneration (George et al., 1995), so evaluating their production in axons is important. In plants, TIR NADases are important immune receptors, and the TIR-dependent generation of a variant of cADPR can be used as a biomarker to detect TIR NADase activation in response to pathogen invasion (Wan et al., 2019). Here we sought to assay SARM1 NADase breakdown products as potential biomarkers of SARM1 activity in axons.

We demonstrate that cADPR is a gene-dosage sensitive biomarker of SARM1 activity in mouse. Levels of cADPR are dependent on SARM1 in uninjured cultured neurons, brain, and sciatic nerve, demonstrating that SARM1 is a major producer of cADPR in neurons. SARM1 is autoinhibited under basal conditions and activated by injury (Gerdts et al., 2013), however these findings demonstrate that SARM1 has a low level of basal activity even in healthy neurons. Upon injury, there is a SARM1-dependent rise in cADPR levels that occurs well before axonal breakdown. Moreover, this rise in cADPR is sensitive to SARM1 gene dosage, with an approximately 50% reduction in SARM1 heterozygous mice. Using subtoxic doses of mitochondrial inhibitors that do not induce axonal degeneration, we show that cADPR can report the activation of SARM1 in compromised axons that are not destined to degenerate. Although cADPR is a potent calcium mobilizing agent, all efforts to manipulate cADPR levels showed no effect on axotomy-induced axon degeneration. Hence, while cADPR is an excellent SARM1 biomarker we could not find evidence that it plays a functional role in the degeneration mechanism. Finally, we show that plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL), a translatable biomarker useful in human studies of neurodegeneration (Khalil et al., 2018; Olsson et al., 2019), is also a biomarker of SARM1 function in degenerating axons. Hence, we identify cADPR as a proximal biomarker of SARM1 activity in axons and NfL as a distal biomarker of SARM1-dependent axonal breakdown. Together, these biomarkers will greatly facilitate the identification of neurodegenerative diseases in which SARM1 is active and target validation studies of SARM1 inhibitors in both animal models and human studies.

Materials and methods

Mouse

For DRG neuronal culture and tissue metabolite analysis (Figure1C, D), CD1 mice and SARM1 knockout and its littemate control mice (C57/BL6; (Kim et al., 2007; Szretter et al., 2009)) were housed (12 hr dark/light cycle and less than 5 mice per cage) and used under the direction of institutional animal study guidelines at Washington University in St. Louis. Sciatic and optic nerve surgery protocols received institutional IACUC approval. Mice were anesthetized in Isoflurane. For optic nerve crush, the optic nerve was exposed by an incision in the conjunctiva next to the globe and the conjunctiva was retracted by rotating the globe. The optic nerve was grasped with cross action forceps and clamped for 10 seconds. Subsequently, local anesthesia was applied via eye solution followed by eye ointment to prevent drying of the eye. For sciatic nerve transection, animals received a skin incision at mid-thigh level and the sciatic nerve was exposed taking care to minimize damage to surrounding tissues. A 1-2 mm piece was cut 5 mm distal from the proximal nerve to prevent re-attachment of the cut ends. Finally, the skin was closed using fine surgical suture. Animals were kept warm until fully recovered.

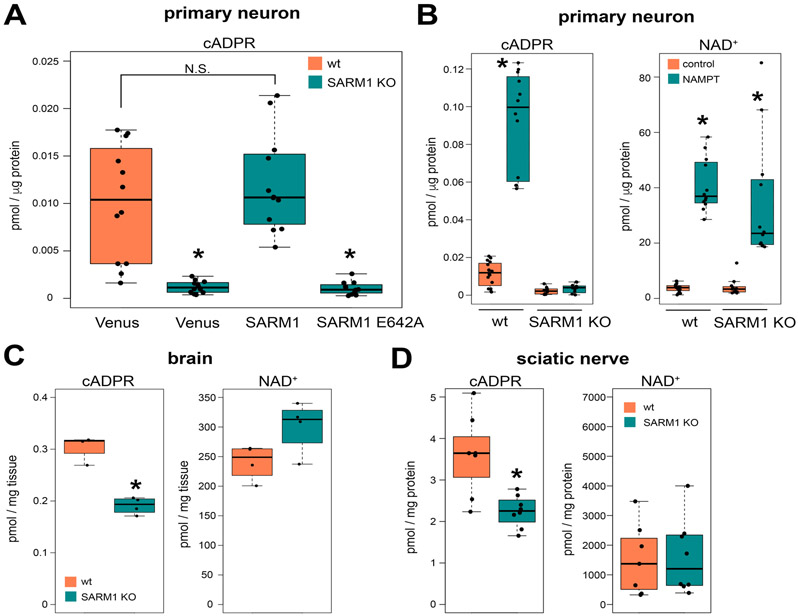

Figure 1. SARM1 is a major cADPR producing enzymes in neurons.

cADPR and NAD+ levels in cultured DRG neurons (A, B), brains (C), or sciatic nerves (D). (A) Intracellular cADPR in wild type (wt) or SARM1 KO DRG neurons expressing Venus fluorescent protein (control), SARM1, or catalytically inactive SARM1 (E642A). Wild type (wt) or SARM1 KO DRG neurons were infected with lentivirus expressing each protein and metabolites were extracted and measured using LC-MS/MS as described in the methods. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=12-16). F(3,44) = 131.9, p<1.5x10−9. *p<1x10−5. (B) Intracellular cADPR and NAD+ levels in wt or SARM1 KO DRG neurons expressing Venus (control) or NAMPT. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=12-16). F(3,48) = 131.9, p<2x10−16 for cADPR and F(3,48)=36.69, p=1.78x10−12 for NAD+ (n=12-16). *p<1x10−6. (C) Brain cADPR and NAD+ levels in wt or SARM1 KO mice. Statistical analysis between wt and SARM1 KO was performed by Mann-Whitney test (n=4 for each genotype). *p<0.05. (D) Sciatic nerve cADPR and NAD+ levels in wt or SARM1 KO mice. Statistical analysis between wt and SARM1 KO was performed by Mann-Whitney test (n=7-8 for each genotype). *p<0.001. Data show the first and third quartile (box height) and median (line in the box) ± 1.5 times the interquartile.

cDNA

Lentivirus transfer vector constructs harboring cDNAs including Venus, cytNMNAT1, SARM1, SARM1 (E642A) were previously described (Essuman et al., 2017; Gerdts et al., 2013; Sasaki et al., 2009). The synthetic DNA fragment encoding ADPRM mutant (ADPRM-QM, (Ribeiro et al., 2018)) and CD38 mutant (sCD38-DM, (Zhao et al., 2011)) were cloned into lentivirus transfer vector FUGW (Araki et al., 2004). Briefly the synthetic DNA fragment (IDT) encoding human ADPRM with mutations (F37A, L196F, V252A, and C253G) was cloned using InFusion (Clontech) reaction. CD38 without 45 N-terminal amino acid with two mutations (E146A and T221F) was PCR amplified from pLX304 CD38-V5 (Clone ID: TOLH-1518440, Transomic Technologies) and cloned into lentivirus transfer vecot FUGW (Araki et al., 2004).

DRG culture and axon degeneration assay

Mouse DRG culture was performed as described before (Sasaki et al., 2009). Mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG) was dissected from embryonic days 13.5 CD1 mouse embryo (50 ganglia per embryo) and incubated with 0.05% Trypsin solution containing 0.02% EDTA (Gibco) at 37°C for 15 min. Then cell suspensions were triturated by gentle pipetting and washed 3 times with the DRG growth medium (Neurobasal medium (Gibco) containing 2% B27 (Invitrogen), 100 ng/ml 2.5S NGF (Harlan Bioproduts), 1 μM uridine (Sigma), 1 μM 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (Sigma), penicillin, and streptomycin). Cells were suspended in DRG growth medium at a ratio of 100 μl medium/50 DRGs. The cell density of these suspensions was ~7x106 cells/ml. Cell suspensions (1.5 μl/96 well, 10 μl/24 well) were placed in the center of the well using either 96- or 24-well tissue culture plates (Corning) coated with poly-D-Lysine (0.1 mg/ml; Sigma) and laminin (3 μg/ml; Invitrogen). Cells were allowed to adhere in humidified tissue culture incubator (5% CO2) for 15 min and then DRG growth medium was gently added (100 μl/96 well, 500 μl/24 well). For Fig. 2B, 1 million cells as 10 μl spotted culture in 24 well plate were used with 1 ml DRG growth medium. Lentiviruses were added (1-10×103 pfu) at 1–2 days in vitro (DIV) and metabolites were extracted or axon degeneration assays (Sasaki et al., 2009) were performed at 6–7 DIV. When using 24 well DRG cultures, 50% of the medium was exchanged for a fresh medium at DIV4. For axotomy experiments, cell bodies and axons were separated.

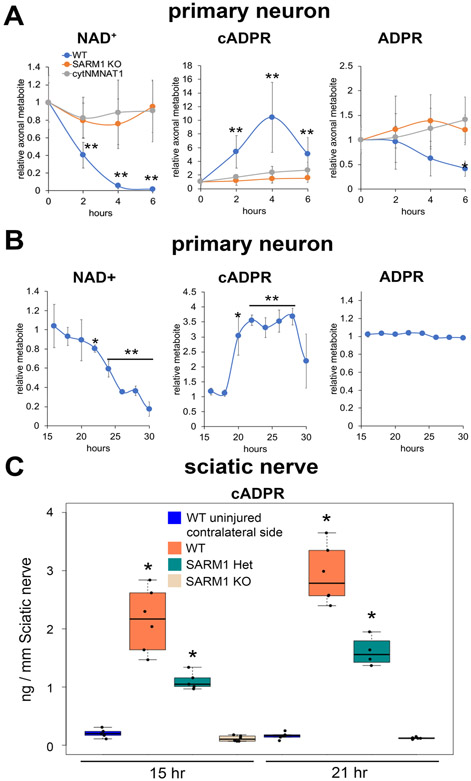

Figure 2. cADPR is significantly increased in injured axons.

(A) Axonal NAD+, cADPR, and ADPR levels were quantified via LC-MS/MS at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 hours post axotomy of cultured DRG neurons. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=12-20). F(11,156) = 40, p=2x10−16 for NAD+, F(11,156) = 30, p=2x10−16 for cADPR, and F(11,156) = 8, p=1x10−10 for ADPR. **p<1x10−3, p*1x10−2 denotes a significant difference compared with wt 0hr post axotomy. (B) Axonal NAD+, cADPR, and ADPR levels were quantified using LC-MS/MS at 15 to 30 hours after vincristine treatment of cultured DRG neurons. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=2-3 for each time point). F(14,29) = 50, p=2x10−16 for NAD+, F(14,29) = 19, p=6.7x10−11 for cADPR, and F(14,29) = 12, p=1.2x10−8 for ADPR. **p<1x10−3, p*1x10−2 denotes a significant difference compared with 15 hours post vincristine addition. (C) Sciatic nerve cADPR and NAD+ were quantified at 15 or 24 hours post axotomy in wt, SARM1 heterozygotes (Het) or SARM1 KO sciatic nerves using LC-MS/MS. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=4-6 mice for each condition). F(3,18) = 60, p=1.5x10−9 for 15 hours post axotomy and F(3,18) = 133, p=1.8x10−12 for 21 hours post axotomy. **p<1x10−4 denotes a significant difference compared with uninjured contralateral side. Data show the first and third quartile (box height) and median (line in the box) ± 1.5 times the interquartile.

Lentivirus

Lentiviruses were produced in HEK293T cells as previously described (Araki et al., 2004). Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells per 35 mm well on the day before transfection. FCIV lentivirus transfer vectors (400 ng) was co-transfected with VSV-G (400 ng) and pSPAX2 (1.2 μg) using X-tremeGene (Roche). The virus containing medium was collected at 3–5 days after transfection. The lentivirus particles (1–105 x 106 infectious particles/ml) were collected from the cleared culture supernatant with Lenti-X concentrator (Clontech) and resuspended in the 1/10 original volume of PBS, and stored at −80°C.

Metabolite extraction

Metabolites extraction from DRG neurons: at DIV6, tissue culture plates were placed on ice and culture medium replaced with ice-cold saline (0.9% NaCl in water, 500μl per well). For collection of axonal metabolites, cell bodies were removed using a pipette. For collection of intracellular metabolites, saline was removed and replaced with 160 μL ice cold 50% MeOH in water. The axons were incubated for a minimum of 5 min on ice with the 50% MeOH solution and then the solution was transferred to tubes containing 50 μl chloroform on ice, shaken vigorously, and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The clear aqueous phase (140 μl) was transferred into a microfuge tube and lyophilized under vacuum. Lyophilized samples were stored at −20°C until measurement.

Tissue metabolites extraction in Figures 1C-D: tissues were collected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Frozen tissues were homogenized by sonication (Branson Sonifier 450, output 2.5, 50% duty cycle, 10- 20 sec) in 50% MeOH in water (10 μl/mg tissue). Homogenates were centrifuged (13,000 g, 10 min, 4°C) and cleared supernatants were transferred to new tubes. One third volume of chloroform was added to the supernatant, mixed, and centrifuged (13,000 g, 10 min, 4°C). The aqueous phase (100 μl) was transferred to a new tube and lyophilized and stored at −20°C until analysis. Lyophilized samples were reconstituted with 5 mM ammonium formate (50 μl for the brain 15 μl for the sciatic nerve), centrifuged (13,000 g, 10 min, 4°C), and 10 μl clear supernatant was loaded on LC-MS.

Tissue metabolites extraction in Figures 2C and 5: at time of tissue collection animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the optic or sciatic nerves were quickly removed and placed on an ice cold metal plate. The length of the individual nerve sample was measured using digital calipers, after removing the swollen end near the site of transection or crush. Tissues were transferred to pre-filled collection tubes (CK28 Precellys tube, Bertin technologies) with 1 mL ice-cold accetonitrile (Carlo Erba) in water (Fischer chemical) mixed with 1% formic acid (Acros organic) (3:1). Tubes were thawed on ice and homogenized with 10 μl of 2-chloroadenosine (2 ng/μl), used as an internal standard. The samples were ground three times at 4500 rpm for 90 sec with a Precellys Evolution (Bertin Technologies, Aix en Provence, France). The homogenate was centrifuged at 4°C (4500 g for 5 min) and 900 μl of the supernatant were transferred to a borosilicate tube. The sample was ground again in 1.1 ml of a solution of acetonitrile / water 1% formic acid (3:1) three times at 4500 rpm for 90 sec. After centrifugation, 900 μl of the supernatant were transferred to the same borosilicate tube. The combined extracts were evaporated to dryness at 40°C in a Genevac EZ-2 Plus Evaporator (Genevac, Ipswich, UK).

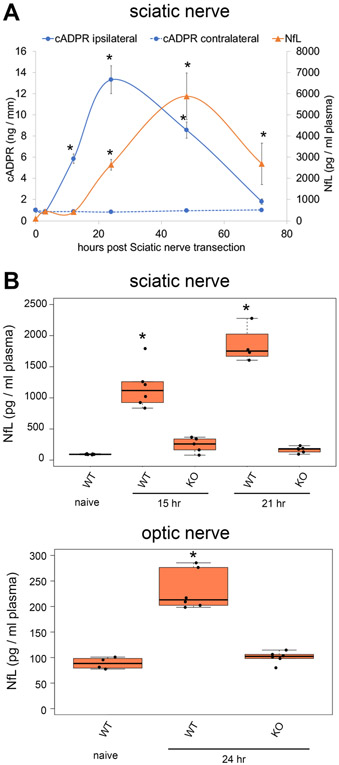

Figure 5. NfL increase after axonal injury is SARM1-dependnent.

(A) Sciatic nerve cADPR levels were quantified in axotomized (ipsilateral) and control (contralateral) sciatic nerves at 0, 3, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours post axotomy. Plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL) levels were quantified from mouse plasma collected at 0,3,12,24,48,72 hours post sciatic nerve axotomy. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA and Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=5-6). F(11,59) = 414, p=2x10−16 for cADPR and F(5,30) = 78, p=2.5x10−16 for NfL. *p<1x10−6 denotes a significant difference from cADPR or NfL levels compared with 0 hour post axotomy samples. (B) Plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL) levels were quantified from wild type (WT) or SARM1 KO (KO) mice (naïve) and mice receiving sciatic nerve axotomy (15 or 21 hours post injury, top panel) or optic nerve injury (24 hours post injury, bottom panel). Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA and Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=4-6 for mice with or without sciatic nerve axotomy and n=4-6 for mice with or without optic nerve injury). F(4,22) = 68, p=4.4x10−12 for NfL levels after Sciatic nerve injury and F(2,13) = 52, p=6.2x10−7 for NfL levels after optic nerve injury. *p<1x10−5 denotes a significant difference from NfL levels compared with wt naive samples. Data show the first and third quartile (box height) and median (line in the box) ± 1.5 times the interquartile.

Metabolite measurement

Metabolite measurements for Figs 1, 2A, 3, and 4: lyophilized samples were reconstituted with 5 mM ammonium formate (15 μl), centrifuged (13,000 g, 10 min, 4°C), and 10 μl clear supernatant was analyzed. NAD+, cADPR, and ADPR were measured using LC-MS/MS (Hikosaka et al., 2014; Sasaki et al., 2016). Samples were reconstituted with 5mM ammonium formate and injected into C18 reverse phase column (Atlantis T3, 2.1 x 150 mm, 3 μm; Waters) equipped with HPLC system (Agilent 1290 LC) at a flow rate of 0.15 ml/min with 5 mM ammonium formate for mobile phase A and 100% methanol for mobile phase B. Metabolites were eluted with gradients of 0–10 min, 0–70% B; 10–15 min, 70% B; 16–20 min, 0% B. The metabolites were detected with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent 6470 MassHunter; Agilent) under positive ESI and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode using parameters specific for each compound (NAD+ (Sigma), 664>428, fragmentation (F) = 160 V, collision (C) = 22 V, and cell acceleration (CA) = 7 V: cADPR (Sigma), 542>428, F = 100 V, C = 20 V, and CA = 3 V: ADPR (Sigma), 560>136, F = 50 V, C = 40 V, and CA = 7 V). Serial dilutions of standards for each metabolite in 5 mM ammonium formate were used for calibration. Metabolites were quantified by MassHunter quantitative analysis tool (Agilent) with standard curves and normalized by the protein (DRG neurons and sciatic nerves) or tissue weight (brains).

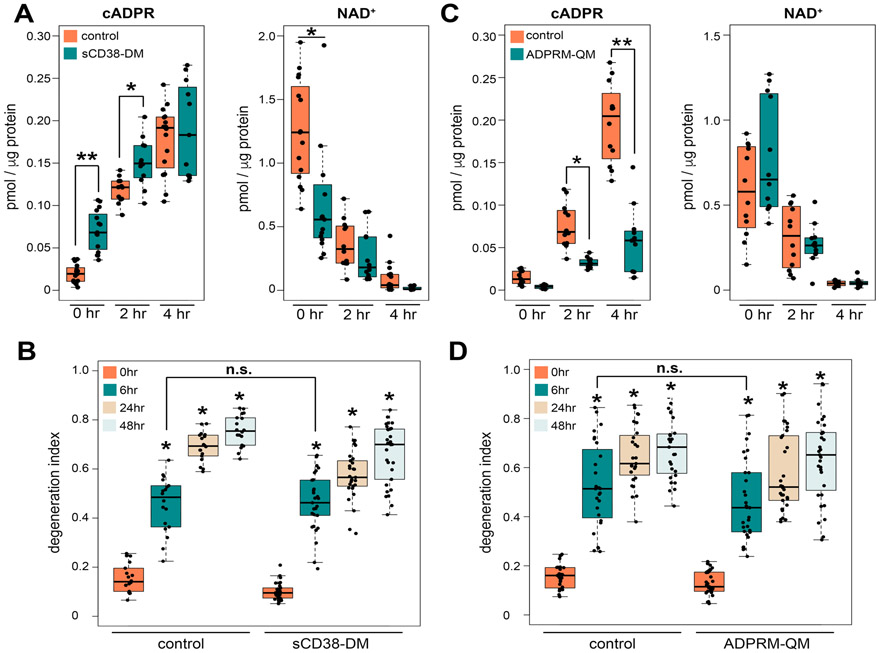

Figure 3. Manipulating the level of cADPR does not alter the time course of axon degeneration.

(A) Axonal cADPR and NAD+ levels were quantified at 0, 2, 4 hours after axotomy using LC-MS/MS. Axonal metabolites were extracted from Venus (control) or sCD38-DM expressing DRG neurons. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=11-15). F(5,75) = 60, p=2x10−16 for cADPR and F(5,75) = 30, p=2x10−16 for NAD+. ***p<1x10−10, **p<1x10−3, *p<0.05 denotes a significant difference from metabolite levels in control axons at each time post axotomy. (B) Axonal degeneration was quantified using the degeneration index of Venus (control) or sCD38-DM expressing DRG neurons from 0 to 48 hours post axotomy. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=14-29). F(7,180) = 160, p=2x10−16. *p<2x10−16 denotes significant difference from degeneration index of control 0 hour post axotomy. (C) Axonal cADPR and NAD+ levels were quantified at 0, 2, 4 hours after axotomy using LC-MS/MS. Axonal metabolites were extracted from Venus (control) or ADPRM-QM expressing DRG neurons. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=12). F(5,66) = 80, p=2x10−16 for cADPR and F(5,66) = 27, p=7.4x10−15 for NAD+. ***p<1x10−15, **p<0.0015 denotes a significant difference from metabolite levels in control axons at each time post axotomy. (D) Axonal degeneration was quantified using the degeneration index of Venus (control) or ADPRM-QM expressing DRG neurons from 0 to 48 hours post axotomy. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=27-31). F(7,223) = 72, p=2x10−16. *p<2x10−16 denotes a significant difference from degeneration index of control 0 hour post axotomy. Data show the first and third quartile (box height) and median (line in the box) ± 1.5 times the interquartile.

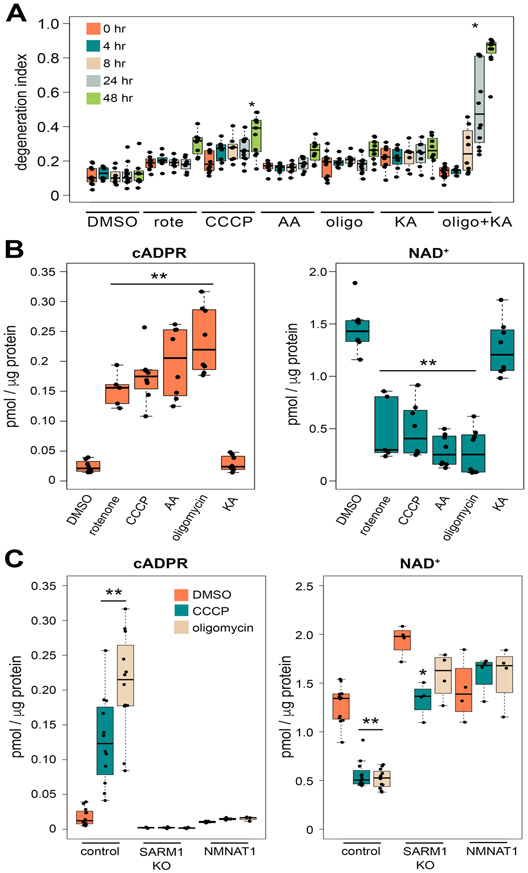

Figure 4. Mitochondria dysfunction induces a SARM1-dependent increase in the levels of cADPR.

(A) Axonal degeneration was quantified the using degeneration index of DMSO, rotenone (rote), CCCP, antimycin A (AA), oligomycin (Oligo), koningic acid (KA) or oligomycin with koningic acid (oligo + KA) treated DRG neurons from 0 to 48 hours post chemical addition. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA and Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=8-12). F(34,292) = 31, p=2x10−16. *p<1x10−13 denotes significant difference from degeneration index of post 0 hour DMSO treated axons. (B) Axonal cADPR and NAD+ levels were quantified using LC-MS/MS at 6 hours after the addition of DMSO, rotenone, CCCP, antimycin A (AA), oligomycin, or coningic acid (KA) to DRG neurons. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA and with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=5-8). F(5,39) = 39, p=4.2x10−14 for cADPR and F(5,39) = 38, p=5.2x10−14 for NAD+. *p<1x10−6 denotes a significant difference from metabolite levels in axons treated with DMSO. (C) cADPR and NAD+ levels were quantified in wt (control), SARM1 KO, or cytNMNAT1 expressing (NMNAT1) DRG neurons at 6 hours after the addition of DMSO, CCCP, or oligomycin using LC-MS/MS. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA and Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=4-12). F(8,51) = 25, p=5.7x10−15 for cADPR and F(8,51) = 52, p=2x10−16 for NAD+. *p<1x10−5 , *p<1x10−3 denotes a significant difference from metabolite levels compared with DMSO treated neurons in each group (control, SARM1 KO, or NMNAT1). Data show the first and third quartile (box height) and median (line in the box) ± 1.5 times the interquartile.

Metabolite measurement for Fig. 2C and 5: sciatic and optic nerve metabolite measurement. The lyophilized samples were reconstituted in 100 μl of 5 mM ammonium formate, of which 75 μl was used for analysis by online solid phase extraction coupled with liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (XLC-MS/MS) as described below.

Metabolite measurement for Fig. 2B: Lyophilized samples were thawed on ice and suspended in 90 μl of water with 5mM ammonium formate (Sigma Aldrich). The homogenized solution was transferred in injection vials and mixed with 10 μL of internal standard (2-chloroadenosine at 2 ng/μL), of which 75 μL was used for analysis by online solid phase extraction coupled with liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (XLC-MS/MS).

Supernatants from DRG neurons were stored frozen in 1.5mL Eppendorf tubes, thawed on ice and 10 μL were transferred in an injection vial and mixed with 80 μL of water with 5 mM ammonium formate and 10 μL of internal standard (2-chloroadenosine at 2 ng/μL). 75 μL were used for analysis by online solid phase extraction coupled with liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (XLC-MS/MS) as described below.

Online solid phase extraction coupled with liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (XLC-MS/MS): samples were injected into a SPE cartridge (2 mm inside diameter, 1 cm length, packed with C18-HD stationary phase), part of a SPE platform from Spark Holland (Emmen, The Netherlands). Thereafter the SPE cartridge was directly eluted on an Atlantis T3 column (3μm, 2.1 x 150 mm) from Waters (Milford, MA, USA) with a water/methanol with 5 mM ammonium formate gradient (0% B for 0.5 min, 0 to 40 %B in 6 min, 40 to 60 %B in 1 min, 60 to 100 %B in 1 min, 100% B for 1 min and back to initial conditions), at a flow rate of 0.15 mL/min to the mass spectrometer. Metabolites (NAD, ADPR and cADPR) and the internal standard 2-chloroadenosine were analysed on a Quantiva triple quadrupole (Thermo Electron Corporation, San Jose, CA, USA). Positive electrospray was performed on a Thermo IonMax ESI probe. To increase the sensitivity and specificity of the analysis, we worked in multiple reaction monitoring and followed the MS/MS transitions: NAD+ MH+, 664.1–136.1; ADPR MH+, 560.1–136.1; cADPR MH+, 542.1–136.1; 2Cl-Ade MH+, 302.1–170.1. The spray chamber settings were as follows: heated capillary, 325°C; vaporizer temperature, 40°C; spray voltage, 3500 V; sheath gas, 50 arbitrary units; auxiliary gas 10 arbitrary units. Calibration curves were produced by using synthetic NAD, ADPR, cADPR and 2-chloroadenosine (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). The amounts of metabolites in the samples were determined by using inverse linear regression of standard curves. Values are expressed as ng per 100,000 cells for axons, ng/mL for supernatant and ng/mm of tissue for the nerves.

Plasma NfL measurement

Blood plasma (120 μl) was collected from the facial vein into a 200 μl K-EDTA Sarstedt tubes . Samples were placed on ice and centrifuged as early as possible for 5 min, at 10.000 g and 4°C. Plasma NfL was measured by ELISA using the NF-Light ELISA kit from Uman Diagnostics (Umeå, Sweden) using the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Sample number (n) was defined as the number of cell culture wells that were independently manipulated and measured or the number of mice. Data comparisons were performed using Mann-Whitney test (two group comparison) or one-way ANOVA using R. F and P values for ANOVA were reported for each comparison in corresponding figure legends. For multiple comparisons, the Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison method was used.

Results

Basal SARM1 activity is a major source of cADPR in the nervous system.

SARM1 is an inducible NADase activated in the injured and diseased nervous system to drive pathological axon degeneration. Purified SARM1 catalyzes the cleavage of the nicotinamide-ribosyl bond of NAD+ and produces nicotinamide (Nam) as well as either ADPR or the cyclic form of ADPR (cADPR) in vitro (Essuman et al., 2017). In an effort to identify an in cell and in vivo biomarker of SARM1 activity, these metabolites were extracted and measured from wild type and SARM1 KO DRG neurons using LC-MS/MS. While the levels of NAD+, Nam, and ADPR were quite similar between neurons of these two genotypes, cADPR was lower in SARM1 KO neurons than in wild type neurons (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. S1). This result was unexpected because SARM1 is autoinhibited and the current model for SARM1 function posits that it is only activated in neurons upon injury. To further examine whether SARM1 is active in uninjured neurons, we expressed either wild type SARM1 or a catalytically inactive SARM1 mutant, SARM1(E642A), in SARM1 KO DRG neurons. Expression of wild type SARM1 in SARM1 KO neurons rescues cADPR to the level present in wild type neurons (Fig. 1A). Moreover, this increase in cADPR requires SARM1 catalytic activity, as the SARM1(E642A) mutant does not lead to an increase in cADPR. These findings are consistent with cADPR being a product of SARM1 NAD+ cleavage in neurons, and suggest that there is basal SARM1 activity in uninjured neurons. We did not detect significant differences in NAD+, Nam, or ADPR (Supplementary Fig. 1) in these neurons, suggesting that other enzymes play a more significant role in determining the steady state levels of these metabolites.

While overexpressed SARM1 is clearly active in uninjured neurons, the low basal levels of cADPR in neurons made examining baseline activity of endogenous SARM1 problematic (Fig. 1A). To overcome this difficulty, we boosted levels of the SARM1 substrate NAD+ via overexpression of the NAD+ biosynthetic enzyme NAMPT in both wild type and SARM1 KO DRG neurons. Expression of NAMPT leads to an approximately 10-fold increase in the levels of NAD+ in both neuronal populations. With this large increase in SARM1 substrate, we now detect an approximately 10-fold increase in the levels of cADPR in wild type neurons. In SARM1 KO neurons there is no increase in cADPR despite the large increase in NAD+ (Fig. 1B). These findings indicate that a) endogenous SARM1 is basally active in neurons and b) SARM1 is the major producer of cADPR in DRG neurons.

The data above demonstrate that SARM1 generates cADPR in uninjured cultured neurons, however cell culture is inherently stressful and so some small fraction of cells may be degenerating. To test rigorously the hypothesis there is basal SARM1 enzyme activity, we investigated whether SARM1 is a significant producer of cADPR in vivo. Metabolites were extracted and measured from the brain and sciatic nerve of wild type and SARM1 KO mice. cADPR levels in both the brain and sciatic nerve of SARM1 KO animals were approximately 40% lower than in the corresponding wild type tissues (Fig. 1C and D). In concert, NAD+ levels in the brain and sciatic nerve of SARM1 KO animals were modestly increased compared to wild type, however the differences were not statistically significant. These results indicate that SARM1 enzyme activity is a major contributor to baseline levels of cADPR in the nervous system, but only contributes modestly to the regulation of baseline NAD+ levels. However, this likely understates the role of SARM1 in neurons, since these in vivo studies include other cell types. Taken together these studies demonstrate that the SARM1 NADase is active in vitro and in vivo in the absence of injury or disease, and identifies cADPR as a candidate biomarker of SARM1 activity in the nervous system.

cADPR is a biomarker of SARM1 activity in degenerating axons.

Using NAD+ metabolic flux analysis, we previously demonstrated that the SARM1 NADase is activated by axon injury leading to increased NAD+ consumption. Having demonstrated that SARM1 boosts cADPR levels in healthy neurons, we tested whether SARM1 also leads to an increase in cADPR levels in injured axons. Axonal levels of cADPR, NAD+, and ADPR were measured from neurons expressing cytosolic NMNAT1 (cytNMNAT1), a strong inhibitor of injury-dependent activation of SARM1 (Sasaki et al., 2016), as well as SARM1 KO and wildtype neurons at various times after axotomy. Consistent with previous findings (Gerdts et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2005), axonal NAD+ levels decline in the initial 6 hours after axotomy of wild type neurons (Fig. 2A). This decline in axonal NAD+ is SARM1-dependent, as it is blocked in neurons expressing cytNMNAT1 or lacking SARM1. In wild type axons, cADPR was significantly increased at 2 hours post axotomy, preceding the morphological axon degeneration that starts at ~6 hours post axotomy. The cADPR level increased by approximately 10-fold by 4 hours after axotomy before beginning to decline. The production of cADPR is SARM1-dependent, as cADPR levels in injured SARM1 KO or cytNMNAT1 expressing axons remain at the low baseline level (Fig. 2A). Relative metabolite values for cADPR are shown in Fig. 2A, while absolute values for cADPR in wild type, SARM1 KO, or wild type expressing cytNMNAT1 neurons are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. In addition to axotomy, the neurotoxic chemotherapeutic vincristine also triggers SARM1-dependent axon loss and NAD+ depletion (Geisler et al., 2016; Geisler et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2018). Following treatment of wild type DRG neurons with 20 nM vincristine, axon degeneration occurs between 20-36 hours. During this time there is loss of NAD+ and an increase in cADPR (Fig. 2B). The ADPR levels remain unchanged after axotomy and vincristine treatment, indicating that either ADPR is not a major product of SARM1 in cells or that ADPR is quickly metabolized to other products. These findings indicate that cADPR is a robust biomarker of SARM1 activity in injured axons that is detectable prior to morphological degeneration.

Having identified cADPR as a biomarker of activated SARM1 in injured axons of cultured neurons, we next tested whether an injury-induced and SARM1-dependent cADPR elevation is detectable in vivo and is sensitive to the amount of SARM1. Sciatic nerves were transected from wild type, SARM1 heterozygous mice, or SARM1 homozygous knockout mice and metabolites were extracted and measured from the distal nerve at 15 and 21 hours post axotomy. Consistent with our in vitro findings, there is a dramatic increase in the level of cADPR at 15 and 21 hours after axotomy of wild type sciatic nerves compared to sham injury (contralateral side). This injury-dependent increase in cADPR from injured sciatic nerve is fully blocked in the SARM1 KO animal. Excitingly, the SARM1 heterozygous mice show an approximately 50% reduction in the level of cADPR compared to wild type (Fig. 2C). The increase in cADPR levels in injured nerve occurs well before morphological degeneration that becomes apparent approximately 36 hours after injury (Beirowski et al., 2005). Hence, cADPR is a readily detectable, gene dose-dependent, in vivo biomarker of SARM1 NADase activity that precedes morphological axon degeneration. Indeed, since cADPR basal levels are so low, we predict that axonal cADPR levels will be a very sensitive in vivo measure of SARM1 activity useful in monitoring efficacy of SARM1-directed therapeutics and in identifying disease models where SARM1 activity is a major contributor.

Manipulating the levels of cADPR does not impact the rate or extent of axon degeneration.

cADPR is a potent Ca2+ mobilizing agent, and Ca2+ dysregulation plays an important role in axonal degeneration, thus we hypothesized that SARM1 generation of cADPR is a crucial component of the axon degeneration process. To investigate this possibility, we used engineered enzymes to manipulate the levels of cADPR in axons. First, we elevated cADPR levels in axons via expression of a mutant form of the NADase CD38. This mutant, sCD38-DM, was engineered such that it localizes to the cytosol and significantly increases the production of cADPR compared to wild type CD38 (Zhao et al., 2011). sCD38-DM was expressed in DRG neurons and axonal cADPR was measured before and after axotomy. cADPR was significantly higher in sCD38-DM expressing axons compared with control axons before axotomy (Fig. 3A). However, this increase in cADPR was not sufficient to trigger spontaneous axon degeneration (Fig. 3B). Upon injury, the cADPR levels in sCD38-DM expressing axons were higher for the first 2 hours post axotomy than in control axons, but were elevated similarly to control neurons at 4 hours post-axotomy. Baseline axonal NAD+ levels were decreased in response to sCD38-DM expression compared to control, and showed a robust injury-dependent decline in both conditions. Although sCD38-DM expression increased cADPR levels, it did not alter axon degeneration dynamics (Fig. 3A and B), suggesting that a rise in cADPR is insufficient to promote axon degeneration.

As a second test of a pro-degenerative function for cADPR, we blunted the injury-dependent increase in cADPR via expression of a cADPR catabolic enzyme, ADP-Ribose/CDP-alcohol diphosphatase (ADPRM). ADPRM is a manganese-dependent enzyme with cADPR phosphohydrolase activity, that cleaves cADPR to produce N1-(5-phosphoribosyl)-AMP. An engineered variant of ADPRM (ADPRM-QM) has increased specificity for cADPR and is 20–200-fold more selective for cADPR than other known substrates such as ADPR (Ribeiro et al., 2018). We expressed ADPRM-QM in DRG neurons and axonal cADPR was measured before and after axotomy. Axonal cADPR was slightly lower in ADPRM-QM-expressing neurons in the absence of axotomy, but this difference was not statistically significant. However, the injury-induced increase in axonal cADPR was dramatically reduced in ADPRM-QM-expressing neurons (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the injury-dependent decline in axonal NAD+ was indistinguishable in control and ADPRM-QM-expressing neurons, indicating that the reduction in cADPR is due to increased cADPR catabolism rather than reduced synthesis via alterations in SARM1-mediated NAD+ cleavage. Having strongly blunted the injury-induced increase in cADPR, we tested whether this influenced the timing or extent of axon degeneration. We found no difference in the injury stimulated axon degeneration process in neurons expressing ADPRM-QM vs. control (Fig. 3D). Hence, a dramatic reduction in cADPR levels in injured axons has no detectable influence on the progress of axon degeneration. In summary, neither gain- nor loss-of-function manipulations of axonal cADPR altered the rate or extent of axon degeneration following injury. Hence, we find no evidence that SARM1-dependent cADPR generation is an important contributor to the timing or progress of axon degeneration.

cADPR Reports SARM1 Activation in Response to Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Although cADPR does not contribute functionally to the axon degeneration process, we tested whether this SARM1 activity biomarker could provide new mechanistic insights into axon degeneration. We recently demonstrated that low-levels of mitochondrial toxins, which themselves do not induce axon degeneration, can synergize with the pro-degenerative DLK kinase pathway to induce SARM1-dependent axon degeneration (Summers et al., 2019). These findings are consistent with either of two hypotheses: 1) mitochondrial dysfunction can activate SARM1 to a subcritical level that is not sufficient on its own to trigger axon degeneration or 2) mitochondrial dysfunction does not activate SARM1, but potentiates the ability of other pathways to activate SARM1. Here we used cADPR as a SARM1 biomarker to test whether or not mitochondrial dysfunction can activate SARM1 without inducing axon degeneration. We treated DRG neurons with a range of mechanistically distinct mitochondrial toxins, as well as the glycolysis inhibitor koningic acid. We found that treatment with CCCP (50 μM), koningic acid (500 nM), oligomycin (2 μM), antimycinA (2 μM), or rotenone (5 μM) do not trigger axon degeneration (Fig. 4A). As a positive control for axon degeneration, we co-incubated 2 μM oligomycin with 500 nM koningic acid. As previously reported (Summers et al., 2014), inhibiting both oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis triggers robust axon degeneration (Fig. 4A). Following treatment of DRG neurons with these sub-degenerative doses of mitochondrial or glycolytic inhibitors, we examined axonal metabolites. We detect a robust increase in cADPR in response to all of the mitochondrial toxins, whereas no changes in cADPR were observed after treatment with the glycolytic inhibitor koningic acid (Fig. 4B). These findings suggest that SARM1 can be activated as a consequence of mitochondrial dysfunction.

We focused on oligomycin and CCCP to perform more detailed metabolic analysis in different genetic backgrounds. We measured axonal metabolites from neurons expressing the SARM1 inhibitor cytNMNAT1, as well as SARM1 KO and wildtype neurons that were treated for 6 hours with either oligomycin, CCCP or DMSO (control). Both oligomycin and CCCP lead to a significant drop in NAD+ levels in wild type neurons. This drop in NAD+ is fully SARM1-dependent, as it is blocked both by expression of cytNMNAT1 and in the absence of SARM1. In addition, there is a dramatic increase in cADPR following oligomycin and CCCP treatment that is also fully SARM1 dependent (Fig. 4C). These data demonstrate that modest mitochondrial dysfunction that is insufficient to induce axon degeneration does cause SARM1 activation. Interestingly, the level of cADPR induced by mitochondrial dysfunction is similar to that caused by axotomy (Sup. Fig. 2), demonstrating that there is not a simple relationship between cADPR levels and subsequent axon loss. The findings with mitochondrial inhibitors also demonstrate there are gradations of SARM1 activation, and that some level of SARM1 activity is compatible with axonal survival at least over short time frames. This has important implications for the development of SARM1 directed therapeutics, suggesting that partial inhibition of SARM1 function may be sufficient to block axon degeneration. These findings also highlight the utility of cADPR as a SARM1 biomarker useful in identifying additional contributors to axonal stress.

Nerve cADPR and plasma NfL are complementary biomarkers for the progression of SARM1-dependent axon degeneration in vivo

We demonstrated that changes in the levels of cADPR in the nerve are a useful biomarker of SARM1 activity. Here we compare changes in nerve cADPR to changes in plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL), a clinically useful biomarker of axon loss in many neurodegenerative disorders (Khalil et al., 2018; Olsson et al., 2019). Following unilateral sciatic nerve transection, we harvested distal sciatic nerve and plasma at various times after axotomy. We measured cADPR from nerve and NfL from plasma (Fig. 5A). cADPR levels are elevated ~6-fold by 12 hours after axotomy. At this time there is no detectable change in plasma NfL, consistent with the idea that cADPR is a more proximal biomarker of the axon degeneration program than is the appearance of NfL in the plasma. cADPR continues to rise until 24 hours after axotomy, at which point it is ~13 fold higher than in uninjured nerve. Levels of cADPR at 72 hours after injury are indistinguishable from uninjured nerve, likely because NAD+ levels are now low and so there is little substrate for generating cADPR. Plasma NfL levels also rise and fall following axotomy, but changes in NfL occur more slowly. Plasma NfL levels are unchanged at 12 hrs after injury, a point when cADPR levels are highly elevated. Plasma NfL then rises ~30 fold by 24 hours after axotomy and peaks at 48 hours after axotomy, before declining to levels that are still significantly higher than baseline by 72 hours after injury. A prior, detailed morphological analysis of Wallerian degeneration in a severed sciatic nerve detected the first signs of axon breakdown at 36 hours (Beirowski et al., 2005). Hence, plasma NfL is able to report signs of axon loss before it is detectable via morphological analysis.

SARM1 depletion blocks morphological degeneration of injured nerves; therefore, we asked if SARM1 is also required for the increased plasma NfL levels following injury. We injured sciatic and optic nerves in wild type and SARM1 KO mice and measured plasma NfL. In wild type mice there is a large increase in plasma NfL at 15 hrs and 21 hrs after sciatic nerve axotomy and a much smaller increase at 24 hours after optic nerve crush, demonstrating that this method is sensitive enough to detect a discrete injury to a CNS nerve (Fig. 5B). In contrast, levels of plasma NfL following these injuries in SARM1 KO mice are very similar to levels of NfL from uninjured wild type mice. The very small change seen in the SARM1 KO mice likely reflects tissue damage induced by the surgery. Hence, plasma NfL is a good proxy of axonal damage following nerve trauma, and injury-induced changes in NfL following nerve injury are SARM1-dependent. These findings establish cADPR and NfL as biomarkers of injury-induced SARM1 activation and axon injury that allow for interrogation of a) early SARM1 activation in the nerve via a rise in cADPR, b) subsequent breakdown of axonal integrity assayed by plasma NfL that precedes frank axonal destruction observable via traditional morphological analysis.

Discussion:

Axon degeneration is an early pathological feature of many neurodegenerative disorders. SARM1 is an inducible NAD+ cleaving enzyme that is a central driver of pathological axon loss, and so there is great interest in identifying neurodegenerative diseases in which SARM1 is active and in developing SARM1-directed therapeutics. For both of these efforts it would be extremely useful to have a biomarker of SARM1 activity. The SARM1 NADase can generate cADPR upon cleavage of NAD+, and here we show that cADPR is a biomarker of SARM1 activity in cells and in vivo both under basal conditions and following injury. Moreover, cADPR levels are sensitive to the gene-dosage of SARM1 and can identify sub-degenerative levels of SARM1 activity. In addition, neurofilament light chain is a plasma biomarker of SARM1 activity following neuronal injury, and so could be a translational biomarker of SARM1-dependent axon loss in human studies. These findings will enable target validation of SARM1-directed therapeutics and identification of neurological disease models in which SARM1 promotes axon loss.

cADPR is a biomarker of SARM1 activity

Purified SARM1 catalyzes the cleavage of the nicotinamide-ribosyl bond of NAD+ to produce nicotinamide (Nam) as well as either ADPR or the cyclic form of ADPR, cADPR (Essuman et al., 2017). To identify a potential biomarker, we analyzed SARM1-dependent changes in both its substrate and products and demonstrated that cADPR is a useful biomarker of SARM1 activity in neurons. First, SARM1 regulates the levels of cADPR in healthy neurons. cADPR levels are significantly lower in cultured DRG neurons from SARM KO mice than from wild type mice, and this effect is rescued by expression of catalytically active SARM1. In addition, cADPR levels in both brain and sciatic nerve are significantly lower in SARM1 KO than in wild type mice, demonstrating basal SARM1 activity in the absence of injury. Hence, while SARM1 is autoinhibited in healthy neurons, some fraction of SARM1 is active at rest. Second, cADPR levels increase in compromised axons that are not destined to degenerate. Low levels of mechanistically distinct mitochondrial inhibitors induce a SARM1-dependent rise in cADPR. This has two interesting implications. First, it demonstrates that dysfunctional mitochondria activate SARM1. This is consistent with the recent discovery that mild mitochondrial dysfunction lowers levels of the axon survival factors NMNAT2 and Stathmin 2 that inhibit SARM1 activation (Loreto et al., 2020; Summers et al., 2019). Since mitochondrial dysfunction is a component of many neurodegenerative diseases, SARM1 may be activated in such disorders and contribute to metabolic dysregulation and neurodegeneration. Although metabolic defects associated with mitochondrial inhibition are assumed to be due to direct disruption of mitochondrial metabolism, these findings suggest that at least some of these metabolic changes may be secondary to SARM1-dependent NAD+ consumption. Second, cADPR can detect partial activation of SARM1, which is not possible when relying on axonal degeneration as the sole readout of SARM1 activity. Indeed, we have demonstrated that partial activation of SARM1 lowers the threshold for axon degeneration (Summers et al., 2019). Finally, SARM1 is responsible for the large increase in cADPR that occurs as NAD+ is being consumed in injured axons destined to degenerate. Importantly, this rise in cADPR precedes axon degeneration, and so is an early marker of SARM1 activation. Hence, cADPR is a biomarker of SARM1 activity in healthy, compromised, and degenerating axons.

The identification of such a biomarker will be useful for many studies. First, it is a powerful screening tool to identify neuronal disease models in which SARM1 is active. At present, to show that SARM1 contributes to degeneration in a model of interest requires first generating the disease model in both wild type and SARM1 knockout mice and then assessing whether degeneration is suppressed. This is a time- and labor-intensive process, particularly for late onset disorders. It may now be possible to determine whether cADPR is elevated in the model. While this would not definitively demonstrate that SARM1 is active, it would be a useful screening tool for prioritizing follow up genetic studies. Second, the identification of cADPR as a biomarker should allow for testing of target engagement by candidate SARM1-directed therapeutics. Since SARM1 is a pro-degenerative enzyme there is great interest in generating small molecule inhibitors. Instead of exclusively relying on axonal degeneration as a readout of drug efficacy, measurement of cADPR in either healthy or injured nerves will provide a more proximate and graded measure of SARM1 inhibition in vivo. Indeed, since levels of cADPR are ~50% less in SARM1 heterozygotes, there may be a roughly linear relationship between cADPR levels and the degree of SARM1 inhibition in vivo. Of course, the quantitative relationship between cADPR and SARM1 activity should not be overstated, since cADPR levels will be influenced by other factors such as its half-life. Nonetheless, this is still a major improvement over morphological analysis of axon degeneration which can be impacted by many factors beyond SARM1.

While cADPR is an excellent biomarker of SARM1 activity, it is interesting to consider why neither NAD+ nor ADPR are as useful as biomarkers. SARM1 does regulate NAD+ levels in injured neurons (Gerdts et al., 2015), and so it can be used as a biomarker. However, the levels of NAD+ are also influenced by many other classes of NAD+ cleaving enzymes such as sirtuins and PARPs, as well as countervailing NAD+ biosynthesis. Indeed, in injured axons the NAD+ biosynthetic enzyme NMNAT2 is rapidly lost (Gilley and Coleman, 2010), and this promotes the activation of SARM1 while simultaneously inhibiting NAD+ synthesis. Hence, the loss of NAD+ in injured axons is due to both SARM1 activity and NMNAT2 loss, and so NAD+ levels are a sub-optimal biomarker of SARM1 activity. While ADPR is the major product of the SARM1 NADase in vitro, we did not detect significant SARM1-dependent changes of ADPR either in cells or in vivo. There are a few potential explanations for the lack of change in neuronal ADPR levels as SARM1 cleaves NAD+. First, ADPR may not be the major SARM1-derived product in vivo although it is in SARM1 enzymatic assays in vitro, potentially reflecting additional neuronal regulation of the SARM1 NADase. Second, ADPR may be a major product, but it could be quickly metabolized by other enzymes in the cell such that the increase is not detectable. Finally, SARM1 may convert ADPR to a form that we are unable to detect. Other families of NADases can transfer ADPR to other molecules, such as in the generation of poly ADP ribose (PAR) or for the ribosylation of proteins. Distinguishing among these possibilities may be enabled by studies of heavy labeled NAD+ in order to follow the fate of ADPR.

cADPR and the Mechanism of Axon Degeneration:

We demonstrated that SARM1 enzyme activity is required for axon degeneration (Essuman et al., 2017), however it is not known how the NADase activity induces this process. We do know, however, that a rise in calcium and subsequent calpain activation is a very late event in the degeneration process (Vargas et al., 2015). There are a number of possibilities for the role of the NADase. First, axon degeneration could be triggered by NAD+ depletion resulting from SARM1 NADase activity. Loss of NAD+ would block dozens of biochemical reactions requiring NAD+, including those necessary for both glycolysis and oxidative phosophorylation. Indeed, ATP levels drop after NAD+ declines (Gerdts et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2005) and loss of ATP contributes to axon degeneration (Yang et al., 2015). Loss of ATP will inactivate the ion transporters that are needed to keep cytosolic calcium low and so could explain the late rise in calcium. In support of the model that NAD+ depletion is the proximate cause of axon degeneration, boosting NAD+ biosynthesis can dramatically delay axon degeneration after injury (Sasaki et al., 2016). Second, SARM1 generates both cADPR and ADPR upon cleavage of NAD+, and both cADPR and ADPR mobilize calcium (Fliegert et al., 2007). Hence, either or both of these metabolites could directly induce the rise in calcium that promotes axon degeneration. Here we tested the role of cADPR, using exogenous enzymes to boost and lower cADPR levels. Neither of these impacted the progression of injury-induced axon degeneration. While we may not have altered cADPR levels to a sufficient extent to impact degeneration, our findings are most consistent with the model that cADPR increases do not play a critical role in axon degeneration. Moreover, the protection afforded by raising NAD+ levels (Sasaki et al., 2016) is not consistent with cADPR or ADPR acting as pro-degenerative molecules, since more NAD+ allows for the generation of more cADPR and ADPR and hence should promote rather than inhibit degeneration. Nonetheless, it will be important to test the role of ADPR, and in particular to determine the fate of the ADPR generated by SARM1 cleavage of NAD+. Third, the SARM1 enzyme activity may have other important functions. For example, SARM1 can cleave NADP which should disrupt redox balance in the axon (Essuman et al., 2018), and in vitro can generate the potent calcium mobilizing agent NaADP via a base exchange reaction (Zhao et al., 2019). By analogy to other NADases, SARM1 could have ribosyltransferase activity and transfer ADPR to an acceptor molecule in order to generate a novel, pro-degenerative product. Finally, there may be additional, unrecognized functions of SARM1 that contribute to the process of degeneration, potentially in collaboration with NAD+ depletion. The similarity of the SARM1 TIR domain to TIR domains in innate immune receptors that function to recruit signaling complexes could indicate additional roles for SARM1 as a scaffold. Such a model is consistent with findings in Drosophila in which Axundead, a protein of unknown function, apparently acts downstream of SARM1 in the axon degeneration cascade (Neukomm et al., 2017).

Neurofilament light chain is a candidate translational biomarker of SARM1 activity

Neurofilaments are important structural components of axons, and upon axon loss can be detected in cerebrospinal fluid and blood plasma or serum (Khalil et al., 2018). Highly sensitive techniques for quantitative measurement of the plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL) have enabled the development of commercially available blood tests for early diagnosis, improved prognostication, and assessment of both disease progression and treatment responsiveness for a wide variety of neurodegenerative disorders including multiple sclerosis, ALS, Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, traumatic brain injury, and peripheral neuropathy (Benatar et al., 2018; Disanto et al., 2017; Ljungqvist et al., 2017; Sako et al., 2015; Sandelius et al., 2018; Weston et al., 2017). Here we demonstrate that NfL is a plasma biomarker of SARM1-dependent axonal loss following traumatic injury to peripheral (sciatic) and central (optic) nerves.

The presence of NfL in plasma is not specific for any particular cause of axon loss, so we predict that NfL will be a useful translational biomarker for SARM1-driven axon degeneration in most disorders in which SARM1 participates. This may be most useful for rapidly assessing the efficacy of SARM1 inhibitors in human clinical trials. Efficacious SARM1 inhibitors that block axon degeneration should result in a decrease in plasma NfL levels. Plasma NfL levels will reflect both the release of new NfL into the plasma from ongoing axon loss as well as turnover of preexisting NfL. While it is reported that NfL has a very long half-life (Millecamps et al., 2007), we find that in response to a discrete injury to sciatic and optic nerves, NfL levels rise for a few days before declining at one week after injury. By this time essentially all axon degeneration is complete, suggesting that in mice NfL levels can fall rapidly once there is no longer a source of newly released NfL. If the half-life of NfL were similar in humans, then a SARM1 inhibitor that successfully blocks axon degeneration should lead to a fairly rapid decline in plasma NfL. Such an early readout of clinical efficacy would greatly facilitate clinical trials for progressive neurodegenerative disorders.

cADPR and NfL are both biomarkers of SARM1 activity, however they are likely to be used for different purposes in future studies. Currently, cADPR is measured in nerves while NfL is measured in plasma, so cADPR may be most useful for animal studies or in human disorders in which nerve biopsies are performed, although molecular imaging approaches could extend its utility to other disorders (Zhu et al., 2018). Since cADPR is a direct product of SARM1 in biochemical assays, it is likely a direct biomarker in vivo. As such, changes in cADPR are a more direct reflection of SARM1 activity. In contrast, NfL is a non-specific marker of axon loss, and so levels of NfL will be sensitive to many factors beyond SARM1. Changes in cADPR occur more quickly than do changes in NfL, since SARM1 is active many hours before axon loss. Hence, cADPR is more useful for mechanistic studies within the axon, such as investigating how injury relieves autoinhibition of SARM1. Finally, cADPR reports subdegenerative levels of SARM1 activity while plasma NfL is expected to rise upon frank axonal loss. Hence, cADPR gives a measure of SARM1 activity in healthy, compromised, and degenerating axons, while NfL will only report on degenerating axons. Moreover, cADPR can be used for studies of reversibility of SARM1 activation, while NfL cannot since axon loss is not reversible. Taken together, cADPR and NfL are complementary biomarkers of SARM1 activity and their identification will spur both mechanistic and translational insights into the processes driving pathological axon degeneration.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1 cADPR, ADPR, NAD+, and Nicotinamide (Nam) levels in cultured DRG neurons.

Metabolites were extracted from wild type (wt) or SARM1 KO DRG neurons and measured using LC-MS/MS as described in the methods. Statistical analysis between wt and SARM1 KO for each metabolite was performed by Mann-Whitney test (n=12). *p<0.0001.

Supplementary Figure 2 cADPR is significantly increased in injured axons. The quantification of axonal cADPR post axotomy from wild type (WT), SARM1 deficient, or cytNMNAT1 expressing neurons. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=12-20). F(11,156) = 40, p=2x10−16 for NAD+, F(11,156) = 28, p=2x10−16. *p<1x10−6 denotes a significant difference compared with wt 0hr post axotomy.

Acknowlegements

We thank members of the DiAntonio and Milbrandt labs and members of Disarm Therapeutics for helpful comments and advice in the preparation of this study. We particularly thank Xianrong Mao for sharing his expertise in SARM1 enzymology.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (AG013730 to J.M. and NS087632 & CA219866 to A.D. and J.M. ).

Abbreviations

- NAD+

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NfL

neurofilament light chain

- CCCP

Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

Footnotes

Competing interests

A.D and J.M. co-founders of and shareholders in Disarm Therapeutics. Y.S. is a consultant to Disarm Therapeutics. R.K., R.O.H., T.M.E., T.B. and R.D. are employees and shareholders of Disarm Therapeutics. The authors have no additional competing financial interests.

References

- Araki T, Sasaki Y, Milbrandt J. Increased nuclear NAD biosynthesis and SIRT1 activation prevent axonal degeneration. Science 2004; 305: 1010–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirowski B, Adalbert R, Wagner D, Grumme DS, Addicks K, Ribchester RR, et al. The progressive nature of Wallerian degeneration in wild-type and slow Wallerian degeneration (WldS) nerves. BMC Neurosci 2005; 6: 6–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benatar M, Wuu J, Andersen PM, Lombardi V, Malaspina A. Neurofilament light: A candidate biomarker of presymptomatic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and phenoconversion. Ann. Neurol 2018; 84: 130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Liu J, Luan Y, Liu Z, Lai H, Zhong W, et al. Sarm1 Gene Deficiency Attenuates Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy in Mice. Diabetes 2019; 68: 2120–2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio A Axon degeneration: mechanistic insights lead to therapeutic opportunities for the prevention and treatment of peripheral neuropathy. Pain 2019; 160 Suppl 1: S17–S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disanto G, Barro C, Benkert P, Naegelin Y, Schädelin S, Giardiello A, et al. Serum Neurofilament light: A biomarker of neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol 2017; 81: 857–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essuman K, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, Mao X, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J. The SARM1 Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor Domain Possesses Intrinsic NAD+Cleavage Activity that Promotes Pathological Axonal Degeneration. Neuron 2017; 93: 1334–1343.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essuman K, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, Mao X, Yim AKY, DiAntonio A, et al. TIR Domain Proteins Are an Ancient Family of NAD+-Consuming Enzymes. Curr. Biol 2018; 28: 421–430.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegert R, Gasser A, Guse AH. Regulation of calcium signalling by adenine-based second messengers. Biochem. Soc. Trans 2007; 35: 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Doan RA, Cheng GC, Cetinkaya-Fisgin A, Huang SX, Höke A, et al. Vincristine and bortezomib use distinct upstream mechanisms to activate a common SARM1-dependent axon degeneration program. JCI Insight 2019; 4: 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Doan RA, Strickland A, Huang X, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A. Prevention of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy by genetic deletion of SARM1 in mice. Brain 2016; 139: 3092–3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Huang SX, Strickland A, Doan RA, Summers DW, Mao X, et al. Gene therapy targeting SARM1 blocks pathological axon degeneration in mice. J. Exp. Med 2019; 216: 294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EB, Glass JD, Griffin JW. Axotomy-induced axonal degeneration is mediated by calcium influx through ion-specific channels. J. Neurosci 1995; 15: 6445–6452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdts J, Brace EJ, Sasaki Y, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J. SARM1 activation triggers axon degeneration locally via NAD+ destruction. Science 2015; 348: 453–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdts J, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J. Sarm1-mediated axon degeneration requires both SAM and TIR interactions. J. Neurosci 2013; 33: 13569–13580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J, Coleman MP. Endogenous Nmnat2 Is an Essential Survival Factor for Maintenance of Healthy Axons. PLoS Biol. 2010; 8: e1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guse AH. Calcium mobilizing second messengers derived from NAD. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015; 1854: 1132–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henninger N, Bouley J, Sikoglu EM, An J, Moore CM, King JA, et al. Attenuated traumatic axonal injury and improved functional outcome after traumatic brain injury in mice lacking Sarm1. Brain 2016; 139: 1094–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka K, Ikutani M, Shito M, Kazuma K, Gulshan M, Nagai Y, et al. Deficiency of nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 3 (nmnat3) causes hemolytic anemia by altering the glycolytic flow in mature erythrocytes. J. Biol. Chem 2014; 289: 14796–14811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsefield S, Burdett H, Zhang X, Manik MK, Shi Y, Chen J, et al. NAD+ cleavage activity by animal and plant TIR domains in cell death pathways. Science 2019; 365: 793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil M, Teunissen CE, Otto M, Piehl F, Sormani MP, Gattringer T, et al. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology 2013 9:12 2018; 14: 577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H-W, Smith CB, Schmidt MS, Cambronne XA, Cohen MS, Migaud ME, et al. Pharmacological bypass of NAD+ salvage pathway protects neurons from chemotherapy-induced degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2018; 115: 10654–10659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungqvist J, Zetterberg H, Mitsis M, Blennow K, Skoglund T. Serum Neurofilament Light Protein as a Marker for Diffuse Axonal Injury: Results from a Case Series Study. J. Neurotrauma 2017; 34: 1124–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto A, Hill CS, Hewitt VL, Orsomando G, Angeletti C, Gilley J, et al. Mitochondrial impairment activates the Wallerian pathway through depletion of NMNAT2 leading to SARM1-dependent axon degeneration. Neurobiology of Disease 2020; 134: 104678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion CM, McDaniel DP, Armstrong RC. Sarm1 deletion reduces axon damage, demyelination, and white matter atrophy after experimental traumatic brain injury. Experimental Neurology 2019; 321: 113040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millecamps S, Gowing G, Corti O, Mallet J, Julien J-P. Conditional NF-L transgene expression in mice for in vivo analysis of turnover and transport rate of neurofilaments. J. Neurosci 2007; 27: 4947–4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neukomm LJ, Burdett TC, Seeds AM, Hampel S, Coutinho-Budd JC, Farley JE, et al. Axon Death Pathways Converge on Axundead to Promote Functional and Structural Axon Disassembly. Neuron 2017; 95: 78–91.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson B, Portelius E, Cullen NC, Sandelius Å, Zetterberg H, Andreasson U, et al. Association of Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Protein Levels With Cognition in Patients With Dementia, Motor Neuron Disease, and Movement Disorders. JAMA Neurol 2019; 76: 318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterloh JM, Yang J, Rooney TM, Fox AN, Adalbert R, Powell EH, et al. dSarm/Sarm1 Is Required for Activation of an Injury-Induced Axon Death Pathway. Science 2012; 337: 481–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Canales J, Cabezas A, Rodrigues JR, Pinto RM, López-Villamizar I, et al. Specific cyclic ADP-ribose phosphohydrolase obtained by mutagenic engineering of Mn2+-dependent ADP-ribose/CDP-alcohol diphosphatase. Scientific Reports 2016 6 2018; 8: 1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako W, Murakami N, Izumi Y, Kaji R. Neurofilament light chain level in cerebrospinal fluid can differentiate Parkinson's disease from atypical parkinsonism: Evidence from a meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci 2015; 352: 84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelius Å, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Adiutori R, Malaspina A, Laura M, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain concentration in the inherited peripheral neuropathies. Neurology 2018; 90: e518–e524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Nakagawa T, Mao X, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J. NMNAT1 inhibits axon degeneration via blockade of SARM1-mediated NAD+depletion. Elife 2016; 5: 1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Vohra BPS, Baloh RH, Milbrandt J. Transgenic mice expressing the Nmnat1 protein manifest robust delay in axonal degeneration in vivo. J. Neurosci 2009; 29: 6526–6534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Vohra BPS, Lund FE, Milbrandt J. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Adenylyl Transferase-Mediated Axonal Protection Requires Enzymatic Activity But Not Increased Levels of Neuronal Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide. J. Neurosci 2009; 29: 5525–5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers DW, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J. Mitochondrial dysfunction induces Sarm1-dependent cell death in sensory neurons. J. Neurosci 2014; 34: 9338–9350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers DW, Frey E, Walker LJ, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A. DLK Activation Synergizes with Mitochondrial Dysfunction to Downregulate Axon Survival Factors and Promote SARM1-Dependent Axon Degeneration. Molecular Neurobiology 2019; 89: 449–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkiew E, Falconer D, Reed N, Höke A. Deletion of Sarm1 gene is neuroprotective in two models of peripheral neuropathy. Journal of the peripheral nervous system : JPNS 2017; 22: 162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ME, Yamagishi Y, Tessier-Lavigne M, Sagasti A. Live Imaging of Calcium Dynamics during Axon Degeneration Reveals Two Functionally Distinct Phases of Calcium Influx. J. Neurosci 2015; 35: 15026–15038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L, Essuman K, Anderson RG, Sasaki Y, Monteiro F, Chung E-H, et al. TIR domains of plant immune receptors are NAD+-cleaving enzymes that promote cell death. Science 2019; 365: 799–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhai Q, Chen Y, Lin E, Gu W, McBurney MW, et al. A local mechanism mediates NAD-dependent protection of axon degeneration. The Journal of Cell Biology 2005; 170: 349–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston PSJ, Poole T, Ryan NS, Nair A, Liang Y, Macpherson K, et al. Serum neurofilament light in familial Alzheimer disease: A marker of early neurodegeneration. Neurology 2017; 89: 2167–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Wu Z, Renier N, Simon DJ, Uryu K, Park DS, et al. Pathological Axonal Death through a MAPK Cascade that Triggers a Local Energy Deficit. Cell 2015; 160: 161–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YJ, Zhang HM, Lam CMC, Hao Q, Lee HC. Cytosolic CD38 protein forms intact disulfides and is active in elevating intracellular cyclic ADP-ribose. J. Biol. Chem 2011; 286: 22170–22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZY, Xie XJ, Li WH, Liu J, Chen Z, Zhang B, et al. A Cell-Permeant Mimetic of NMN Activates SARM1 to Produce Cyclic ADP-Ribose and Induce Non-apoptotic Cell Death. iScience 2019; 15: 452–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X-H, Lu M, Chen W. Quantitative imaging of brain energy metabolisms and neuroenergetics using in vivo X-nuclear 2H, 17O and 31P MRS at ultra-high field. J. Magn. Reson 2018; 292: 155–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziogas NK, Koliatsos VE. Primary Traumatic Axonopathy in Mice Subjected to Impact Acceleration: A Reappraisal of Pathology and Mechanisms with High-Resolution Anatomical Methods. J. Neurosci 2018; 38: 4031–4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 cADPR, ADPR, NAD+, and Nicotinamide (Nam) levels in cultured DRG neurons.

Metabolites were extracted from wild type (wt) or SARM1 KO DRG neurons and measured using LC-MS/MS as described in the methods. Statistical analysis between wt and SARM1 KO for each metabolite was performed by Mann-Whitney test (n=12). *p<0.0001.

Supplementary Figure 2 cADPR is significantly increased in injured axons. The quantification of axonal cADPR post axotomy from wild type (WT), SARM1 deficient, or cytNMNAT1 expressing neurons. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni multiple comparison (n=12-20). F(11,156) = 40, p=2x10−16 for NAD+, F(11,156) = 28, p=2x10−16. *p<1x10−6 denotes a significant difference compared with wt 0hr post axotomy.