Abstract

Background:

Four Appalachian states including Pennsylvania (PA) have the highest drug overdose rates in the country, calling for better understanding of the social and economic drivers of opioid use in the region. Using key informant interviews, we explored the social and community drivers of opioid use in a non-urban Appalachian Pennsylvania community.

Methods:

In 2017, we conducted qualitative interviews with 20 key stakeholders from a case community selected using the results from quantitative spatial models of hospitalizations for opioid use disorders. In small town located 10 miles outside Pittsburgh, PA we asked participants to share their perceptions of contextual factors that influence opioid use among residents. We then used qualitative thematic analysis to organize and generate the results.

Results:

Participants identified several contextual factors that influence opioid use among residents. Three cross-cutting thematic topics emerged: 1) acceptance and denial of use through familial and peer influences, community environments, and social norms; 2) impacts of economic shifts and community leadership on availability of programs and opportunities; and 3) the role of coping within economic disadvantage and social depression.

Conclusion:

Uncovering multi-level, contextual drivers of opioid use can benefit the development of future public health interventions. These results suggest that social and community-level measures of structural deprivation, acceptance and/or denial of the opioid epidemic, community engagement and development, social support, and social depression are important for future research and programmatic efforts in the Appalachian region.

Keywords: opioid use disorders, qualitative research, Appalachian region, social ecological model, social determinants of health

Introduction

Rates of both opioid use disorders (OUDs) and opioid overdoses have risen in rural areas of the United States (Drug Enforcement Agency, 2015). Additionally, a widening burden of “diseases of despair,” including alcohol, prescription drug and illegal drug overdose, and alcoholic liver disease/cirrhosis of the liver, exists between Appalachian and non-Appalachian counties (Case & Deaton, 2017). In this highly rural 13-state region spanning the mountain range from northern Mississippi into southern New York, overdose deaths among those age 25–44 are over 70% higher in Appalachian counties than the rest of the US (Meit, Heffernan, Tanenbaum, & Hoffman, 2017), and four Appalachian states including Pennsylvania (PA) now have the highest drug overdose rates in the country (Beatty & Hale, 2019). While socioeconomic disparities between Appalachia and the rest of the country have improved, the region’s residents have a per capita income that is 74.3% of the national average, and as of 2016, over 17% of the residents are in poverty, with counties with rates as high as 44.3%, compared to the national average of 14.8% (Appalachian Regional Commission, 2014a, 2014b; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2016). These counties also have lower levels of educational attainment and higher levels of unemployment than national averages (Appalachian Regional Commission, 2013, 2014c). The 20-year discrepancy in overall life expectancy that exists between the most and least healthy counties in the US, including the Appalachian region, has been largely attributed to these socioeconomic factors along with reduced health care access and individual behavioral and metabolic risk (Dasgupta, Beletsky, & Ciccarone, 2018). Some of this risk may stem from increases in income inequality, which has contributed to a synergistic relationship between poverty and substance use (Dasgupta et al., 2018). A better understanding of the social and economic drivers of opioid use in the region is needed in order to develop and implement effective interventions.

As a key component of “diseases of despair” (Case & Deaton, 2015, 2017), opioid use and OUD are likely connected to experiences of social distress, such as trauma or disempowerment, along with increased access to and availability of opioids (Dasgupta et al., 2018; Wright et al., 2014); as Appalachia has reduced access to medical providers capable of prescribing opioids (Appalachian Regional Commission, 2017), the social factors may contain particularly vital information. Prior research assessing connections between OUD and place of residence shows that economic and social factors, such as reduced access to medical facilities and cultural norms, combine to create communities with greater vulnerability to substance use (Boardman, Finch, Ellison, Williams, & Jackson, 2001; Cerda et al., 2017; King, Fraser, Boikos, Richardson, & Harper, 2014). These upstream social drivers of OUD support an expanded definition for pain and coping that takes into account a broader perspective including factors such as housing and economic disadvantage, adverse childhood experiences, geographic and social isolation, stigma, and hopelessness, as important contributors to the opioid epidemic (Cloud, Ibragimov, Prood, Young, & Cooper, 2019; Linton, Haley, Hunter-Jones, Ross, & Cooper, 2017; McLean, 2016; Quinn et al., 2016; Rigg, Monnat, & Chavez, 2018; Stein et al., 2017; Werb et al., 2018). Results from recent spatial analyses uncovered connections between contextual factors and opioid overdoses, where areas (operationalized using ZIP codes) with higher poverty and unemployment rates as well as lower educational attainment and median household incomes had higher rates of opioid overdoses (Mair, Sumetsky, Burke, & Gaidus, 2018; Pear et al., 2018). In addition to socioeconomic factors, researchers posit that certain factors, such as social norms about drug use and access to medical care, treatment services, and public transportation may play a stronger role in opioid use in rural environments (Pear et al., 2018; Rigg et al., 2018). These findings suggest the need for determining alternate drivers of OUD and overdose in non-urban areas from those in urban areas.

Few studies have utilized qualitative or mixed method research to explore social or structural facilitators or barriers to use of opioids in non-urban environments. A recent systematic review identified 41 articles using qualitative approaches to describe social and contextual drivers of opioid use initiation (Guise, Horyniak, Melo, McNeil, & Werb, 2017). Of these articles, only nine focused on low- or middle-income environments with only one explicitly addressing a rural population in the US (McLean, 2016). Several themes summarized in the review connect to social and structural factors, such as the normalization of injection drug use within social networks, the role of structurally disadvantaged neighborhoods (e.g., proximity to drug access, unemployment, ways to manage boredom, and ways to gain prestige or money) (Andrade, Sifaneck, & Neaigus, 1999), and opioid use as a coping strategy for dealing with pain or trauma (Khobzi et al., 2008). The article concludes by highlighting the need for qualitative research to explore the enabling and constraining socio-structural contexts of opioid use (Guise et al., 2017).

Because risk contexts include both micro- (e.g., individual or interpersonal) and macro- (e.g., societal) environmental levels of risk across physical, social, economic, and policy contexts (Rhodes, 2002, 2009), the social-ecological framework has been utilized successfully to organize and elucidate the variety of factors affecting substance use and associated high-risk behaviors (e.g., sexual risk-taking, violence) (Baral, Logie, Grosso, Wirtz, & Beyrer, 2013; Connell, Gilreath, Aklin, & Brex, 2010). In addition to helping organize discussions of the multiple levels of influencing factors, the social-ecological framework has the added benefit of encouraging consideration of factors beyond the individual level and highlights opportunities for interventions that target higher ecological levels (e.g., interpersonal or community) including multi-level interventions, which seek to address factors at multiple levels. Following the multi-level structure of the social-ecological framework, wide use of a risk environment perspective among researchers in the field of substance use, where social, cultural, economic, physical, and policy factors intersect to increase potential risk of harm, has expanded the typical focus on individual behaviors to highlight the importance of the contexts in which these behaviors occur (Rhodes, 2002, 2009; Yedinak et al., 2016).

As part of a mixed methods study that combined spatial analyses of hospitalizations for OUDs and qualitative interviews with a variety of key informants in an Appalachian PA community with high opioid use, we explored the social and community drivers of initiation of opioid use, continuation of use, and recovery experiences. We used the social-ecological framework to examine the concentric levels in which social and community-level drivers and risks of opioid use exist in a low-income, small-town community, and in this article, we address the overarching topics that cross-cut these levels to provide novel solutions for addressing the opioid epidemic in non-urban areas.

Methods

Case Community Selection

We used posteriors from hierarchical Bayesian space-time models of hospitalizations for opioid use disorders (OUDs) and community conditions to identify communities with the greatest predicted probabilities of epidemic outbreak (Mair et al., 2018). Models used residential ZIP code polygons in Pennsylvania from 2004–2014 (16,275 space-time units). Counts of OUDs were obtained using ICD-9CM diagnoses from patient-level records of hospitalizations from the Pennsylvania Healthcare Cost Containment Council (PHC4) (Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council (PHC4), 2016). Additional model details can be found in previously published work (Mair et al., 2018; Sumetsky, Burke, & Mair, 2019). Using model results and limiting to ZIP codes with populations of 100+ within a 2-hour drive of Pittsburgh, we selected a discrete target area (i.e., case community) consisting of one ZIP code.

The case community, located close to 10 miles outside of Pittsburgh, is 1.6 miles2 and has a population size of approximately 4,500 people with a household median income of $31,681. The population is 94% white with 15.8% living below the poverty line (United States Census Bureau, 2019). As is common with many communities in the Mon Valley region, an area south of Pittsburgh on the Monongahela River, this case community was founded in the 1890s when companies built factories, mills, and other facilities for steel and glass production as well as gas and coal extraction ([Town] Bicentennial Committee, 1976). The area was primarily settled by Polish, Italian, German, Irish, and Slovak immigrants and reached a population maximum in the 1940s-50s; since the 1970s, this community has experienced an approximately 10% decline per decade as the industrial facilities closed their doors as well as a 51.3% decline in the population age 18 to 24 between 1970 and 2010 (United States Census Bureau, 2017).

Data Collection

In 2017, using snowball sampling methods we identified and interviewed 20 key stakeholders in the case community, including self-identified community leaders, treatment providers, and residents. The research team’s initial contact with the community included a key community leader, which began the snowball sampling process. We asked the participants to describe their role or experience in the opioid epidemic and categorized participants based on these responses. Participants generally described their current relationship to the epidemic, and as we focused on general perceptions of their community rather than probing for individual experiences, participants may have other connections to the epidemic than those described (e.g., a service provider may have an undiscussed history of opioid use). The project participants included community leaders (e.g. town leadership and police representation); treatment providers, which ranged from therapists to those managing or volunteering at recovery houses and treatment centers; and community residents (11 of 20 participants) including three individuals who shared that they were currently using opioids, five with a history of use, and three who were family members of those who currently use or have a history of use. We approached this sample with the goal of seeking a diverse range of thoughts and perceptions about use at a broad community-level rather than specific personal experiences and determined after 20 interviews that we captured a variety of perspectives from participants in diverse roles in the community.

A research assistant with relevant qualitative research training and experience conducted in-depth interviews, which were approximately one hour long. Participants were reimbursed $40 for their time. The interviews were conducted at an agreed upon community site (e.g., coffee shop, community center) and time- and audio-recorded. We used a field guide, composed of semi-structured and open-ended questions, to focus the interviews on identifying perceptions regarding the contextual factors that influence opioid use among residents of the community. The semi-structured format allowed for flexibility and adaptability throughout the interview process as new information arose. For example, participants early in the interview process identified specific locations associated with use, programs and services in and around this community, and trends over time, which we able to intentionally discuss with participants in later interviews. Specific attention was given to the range of contextual factors, including social and structural factors, that influence injection opioid use, dependence, and overdose among community residents. Example questions focusing on these social and contextual factors included: 1) how has prescription drug and heroin use changed in this community in recent years; 2) what are your thoughts about the reasons for changes in use, dependence, and overdose in this community; and 3) what types of resources exist here [in this community] to address opioid use. All work was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s IRB (PRO16080389).

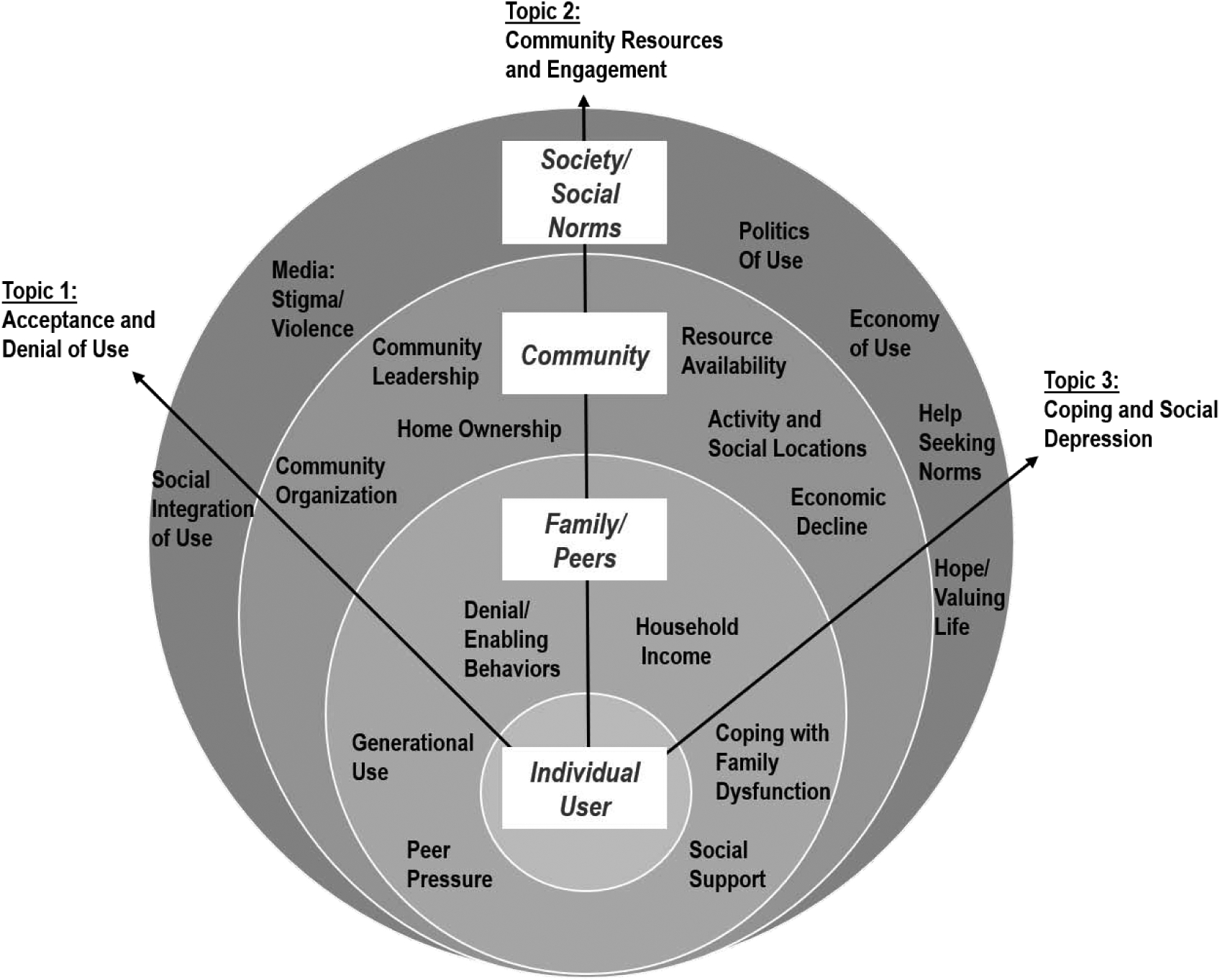

Data Analysis

All audio recordings from the in-depth interviews were transcribed. The principal investigator and two research assistants read the transcripts in their entirety, and the files were imported into the qualitative data management software NVivo (NVivo, 2017), which was used for qualitative text analysis. All segments of text within each interview addressing specific, a priori thematic areas were indexed under a common heading. We began by using the components of the interview field guide and then expanded with more specific codes that we identified as a result of the review and analysis process. Because we used the social-ecological framework to structure the interview questions, we grouped resulting themes into categories reflecting the interpersonal, community, and societal or structural influences of behavior to capture a broad perspective the multi-level factors contributing to the risk environment (Figure 1). Example codes included „Cultural and Social Opioid Use‟ (interpersonal level), ‟Community Engagement‟ (community level), and ‟Environmental and Physical Makeup of the Community‟ (structural/social level).

Figure 1. Emergent Themes within the Social-ecological Model Levels with the Cross-cutting Topic Areas.

Results

In Figure 1, themes are grouped by levels within the social-ecological framework beyond the individual level: interpersonal, community, and structural/societal. Upon review, these emergent themes often cross-cut more than one ecological level, generating three major areas that highlight various social and contextual factors: 1) acceptance and denial of opioid use from familial and peer influences, community environments, and social norms; 2) the impact of changing community resources and engagement, as economic shifts and community leadership affect the availability of jobs, programs, educational opportunities, and activities; and 3) the role of coping within economic disadvantage and social depression, which manifests at the community level and influences individual mental health.

Topic 1: Acceptance and Denial of Use

The first cross-cutting topic we observed in the thematic qualitative results posed a duality of experience connected to and grounded in structural and social inequities found in this economically depressed community. Participants described opioid use in their families, peers, or community as a known, regularly present behavior, accumulating to create a broader social norm of acceptance with effects beyond the individual-level. Alongside this social integration and acceptance of use, they also discussed the co-occurring experiences of denial, or a lack of willingness to accept the presence of use in one‟s own family or community to take action.

Generational Use and Peer Pressure.

The participants recounted a range of social influences, including the social acceptance of opioid use through peer and generational effects. From a family perspective, one participant discussed:

I was in an out of the county jail. I was staying at a friend’s house, back and forth with my mom. My mom uses too, my mom, my brother, my sister, and it’s like it runs in my family.

(Interview 15, resident who currently uses)

Another participant shared thoughts on peer influences, particularly among the young:

I believe that there’s peer pressure with young children, especially school-aged children that want to be socially connected, all right? So, there’s peer pressure amongst their own.

(Interview 7, service provider)

However, despite pervasive and frequent exposures to opioid use, participants described continued denial among family members and loved ones. This discrepancy indicates that family-level variation exists. Some participants reported being commonly around or connected to opioid use at an early age, while other participants spoke about a continued lack of recognition of problems in their own household or community. One participant shed light on the duality of this experience:

And through my experience, the kids today are more immune to the consequences. It’s normal to them now, from the deaths, from the ODs [overdoses], to the killings to the dysfunction, it’s accepted now. The parents now most of them don’t have hope for the kids and deny their part in it, and so you have kids nowadays through all that dysfunction…and through all the pain and the hurt, through generations of dysfunction that most of them have at home.

(Interview 11, resident with a history of use)

Social Integration of Use and the Media.

Building on this interpersonal-level trend, participants also reported norms and external structures, such as the media, that influence use behaviors of residents in their community. As a whole, participants discussed the opioid epidemic as one that is ever-present and thereby socially integrated beyond a family or peer-group level and includes the effects of residents being exposed to opioid use at a community level. One participant explained this integration of use into social norms:

For a lot of my friends, if you have family members that use, it’s either you’re never going to use because you don’t want to be like them, or you’re so curious of why do they that? Like me, why did my mom love this so much where she’d leave us hungry and pick this over us. So that made me curious to try it… I know you lost your kids. I lost my kids, houses, everything. You know all this… why do I keep going back to this drug? And then a part of me sometimes is like this is all I know because I’m a product of my environment. This is how I grew up.

(Interview 15, resident who currently uses)

Another participant described how this duality of denial alongside social integration and acceptance of use also occurs at a broader community level:

The family has denial about what’s really going on…and a community’s going to do that too because the community does not want to be identified as like those other communities. They’d rather be separate and apart from-- because I hear people on the news all the time. Well, I’m so surprised this has happened in my community…But it’s prevalent, more some areas than others, but it’s going on just about everywhere.

(Interview 10, service provider)

Along with broadly visible use within the community, participants discussed the role of the media in simultaneously generating fear and stigma, particularly regarding certain racial groups or communities, and knowledge about the epidemic. For example, one participant reflected how the media plays a role in differences across socioeconomic groups:

People don’t believe that it’s going on, or want to believe it, or a certain segment of the population don’t want to, until they see it in the media, YouTube, social media… And then it kind of raises the eyebrow again, [and not] for poor white folks to get high and die because that’s been happening for a long time over there. The bigger spotlight came when affluent white kids started getting high.

(Interview 5, community leader)

As with experiences at the family level, denial can also manifest alongside prevalent use at a community level, which is further exacerbated by messages individuals receive in underserved communities.

Topic 2: Community Resources and Engagement

The second cross-cutting topic largely reflected economic challenges experienced in the home and at a broader community level. Participants tied challenges with making ends meet together with the economic decline experienced in the community since industry closed the primary sources of employment.

Household Income and Home Ownership.

Participants directly described the connection between the need to find a way to support family and the accessibility of opioid use or distribution. For example, one participant explained:

And you may have individuals that may or may not have the opportunity to get skilled or feel like they can make a family income. Maybe some of them offer an income that will support a single person but not a family. And because it’s so, again, so accessible and there is a need for people to use that, in their minds, becomes their business.

(Interview 10, service provider)

Just as participants drew a connection between the decision to sell opioids to the economic opportunities in the community, others drew a connection between home ownership and perceptions of engagement and connection to the community. A participant elaborates:

Most of them are renters. They don’t own their properties, so you can’t take ownership of somebody else’s property. So, if you’re a renter and not an owner, then you have that kind of mentality where you’re just a part of. You’re not the city.

(Interview 13, service provider)

Participants tied this lack of community engagement or ownership to reduced participation in the community or likelihood for taking action on opioid-related issues.

Resource Availability, Activity and Social Locations, and Community Leadership.

Among other community-level influences, participants described factors related to the absence of neighborhood organizations and resources, which generally reflect a pressing need for social and tangible supports. Participants described the need for resources across a variety of platforms, including activity and social locations for youth and families, treatment services, and more general community resources like grocery stores and healthcare. For example, one participant discussed the lack of resources found nearby:

There should be a resource center. If we’re struggling, there’s no site doctor. There is the three-quarter house but like an IOP [intensive outpatient program]. There’s [a facility several miles away], but some people can’t get to [this facility]. [The local towns] should have their own right around here. You see there’s like 10 dollar stores in [this town]. Why can’t we make one of them into a PCP [primary care physician], psych doctor, an IOP, or just a resource center where anybody should, even without drugs -- domestic violence, I have domestic violence issues too. Anything like that. Or if people are struggling to get their kids back. There’s a lot of resources out there, but some people don’t know where to go to get them.

(Interview 10, service provider)

Participants explained how the presence or absence of these resources can directly affect how people are able to spend time, particularly among younger individuals, resulting in boredom or lack of other activities besides using opioids. For example, one participant stated:

One of the things that’s got a lot to do with it is boredom. I know for me—I know from me being an addict you get boredom and not have nothing, have stuff to do, it can knock you off the square. You figure, ‘Oh, you don’t have nothing to do. I could just have one.’ Knowing an addict, you can’t just have one or anything like that.

(Interview 17, resident with a history of use)

Another participant put this into perspective, while continuing to depict the influence of the social integration and acceptance of use:

When I apply for these jobs, they are not hiring, and there is no work. There is no activities, not only for the kids, I mean there’s playgrounds and what-not, but there is no activities for the younger kids and the older kids. We are talking about the 18-year-olds, the 7 to 18-year-olds… then you talk about the 30-year-olds. And there is nothing to do but get high. I’ve always seen that as normal, so to speak.

(Interview 16, resident with a history of use)

In addition, participants discussed the need for the engagement of community leadership and increased community development among communities experiencing high levels of use. For example, they described the need for police education and engagement and frustrations for how tight budgets and a disconnection between community members and political leaders result in a lack of money spent on needed programs and services. A participant expressed:

And if the police are educated properly, then maybe a few of them may be in a position to make a difference in somebody’s life. Not that they need to be responsible for the whole kit and caboodle, but in conjunction with other integrated services in the community and persons in the community, whether the Mayor and having some kind of task force that’s having some town meeting to just do education first. Not accuse anybody of anything, just education.

(Interview 10, service provider)

Additionally, political leaders reported a lack of certainty for how to improve access to these resources and restrictions in possible ways forward. In this specific small-town community, with a history of declining industry, residents reflected on the economic downturn of their community as mills and industry facilities closed and other businesses left in consequence. One participant described this chain of events:

I think as the mill was closed, and everything closes, other businesses leave, opportunities leave, things for people to do because they don’t have the money to do it no more, everything leaves. When the drugs come in, the education doesn’t come with it. So, it all goes together.

(Interview 18, resident who currently uses)

This change in economy directly affects the availability of jobs and resources to fund programs and educational opportunities, with the lack of social or productive activity locations contributing to individuals using opioids, both as a mechanism to cope with financial issues or other personal problems and as simply something to do.

Topic 3: Coping and Social Depression

The third cross-cutting topic focused on a variety of coping mechanisms at both the interpersonal and community levels. Participants describe the need to cope at both a familial level and for broader social reasons, including norms around hope and help-seeking as well as the financial drivers present in communities that have experienced an economic decline.

Coping with Family Dysfunction and Social Support.

Throughout our interviews, several participants recounted how experiences in their home life affected their initiation of use or contributed to continued use. These experiences range from forms of abuse, violence, neglect, and other challenging family interactions to financial situations that provoke the need to seek opportunities to make ends meet. As one participant related:

It seems like with the economic environment, family situations, violence, gang violence, there is a lot of psychological impacts that it’s having on families. And my assessment would be that how people cope with them is in different ways. And for some people, it’s using substances.

(Interview 10, service provider)

Participants also discussed social support, or lack thereof, as both an aid for coping during recovery and a potential trigger for use depending on the nature of the relationships. Those with prior experience in treatment programs reflected on how different types of new positive support can increase their success at recovery. However, some described how lack of social support contributed directly to initiation of use or increased use, and still others described the need to remove negative influences from their lives to be successful at recovery. A participant reported on the role of social support throughout the course of use and recovery:

I have no family that I really talk to. I burned a lot of bridges. I was very alone, very afraid, and very stuck in my addiction, and was going to stay there. But things changed, and I’ve reached out because I got desperate enough. When you get in enough pain, the drugs don’t work anymore, and you reach out and you try to do something different, which you have to change everything. Everything. So, if you have one person supporting you, it’s progress because they can really help you along.

(Interview 9, resident with a history of use)

Social Depression and Economies of Use.

Additionally, participants described hopelessness and lack of help-seeking behaviors as social norms that may affect opioid use initiation and distribution. One participant expressed:

And those is like old fantasy dreams, fantasy hope. A false hope. And so, there’s no real hope no more. There’s no more real value no more. I mean, the real family values is lost, and the value is get rich quick by any means necessary… and so these kids now, if they’re not going through sports in these little small towns and stuff like that, the only way out is to sell drugs.

(Interview 11, resident with a history of use)

While these perceptions may be connected to cultural norms, such as self-sufficiency, the participants often tied these norms to structural deprivation (e.g., lack of and distance to resources and the physical composition of the community) and relate this pervasiveness as a community-level depression. A participant made this connection between the physical community, social depression, and use:

Because if you know anything about [this area] and you went around here, you would think it’s almost like in a war zone. You see all these abandoned houses in the community. You see lots with grass growing six feet high. You just see trash in the community. It’s just a depressing area. And when people live in a depressed area, they have a tendency to become depressed themselves. And depression leads to something to anesthetize themselves, something like a drug or alcohol just to get through a day, you know?

(Interview 13, service provider)

Finally, participants described larger structural economic and political influences of use in the community. In financially- and opportunity-deprived neighborhoods, other economic prospects become less available and selling becomes more attractive to residents – a fact noticed by those interested in increasing profits. As one participant explained:

The mainstream suppliers, the people that are higher on the drug-dealing chain target these poor neighborhoods because they’re so ready, willing, and able to do anything it takes to make money.

(Interview 12, resident who currently uses)

Discussion

Results from this qualitative research study provide a rich description of how multiple levels of influencing factors relate to opioid use in an interrelated nature in a small-town community in Appalachian PA. These insights support risk factors described in previous works (Andrade et al., 1999; Khobzi et al., 2008; Quinn et al., 2016; Rahmati, Herfeh, & Hosseini, 2018) and offer novel suggestions of the ways that interpersonal, community, and larger societal factors have contributed to the duality of acceptance and denial of use and generated structurally deprived environments that create the need for coping at both the individual level (e.g., dealing with financial or interpersonal stressors) and in broader society (e.g., handling community-level depression) within such communities.

The issues raised at the interpersonal level directly relate to previously proposed rationales for use initiation (Guise et al., 2017; Werb et al., 2018), which suggest there are differences in norms related to opioid use that may vary across, or even within, communities. For example, family and peer influences along with stress and coping with trauma have been connected with opioid use initiation, a pattern also reflected in our results (Rahmati et al., 2018). These themes also reflect those of previous work, which indicates adverse childhood events (Quinn et al., 2016; Stein et al., 2017) as well as coping with pain and trauma are key drivers of opioid use initiation (Khobzi et al., 2008). The participants in this study shed new light on how the acceptance and denial of use for many individuals starts at the family level through generational exposure, propagates with additional experiences at the community level, and co-exists with familial and community-wide denial, which may interfere with needed treatment and resources.

Likewise, the community- and societal-level themes reflect previous analyses that highlight the connections between structural deprivation and opioid use (Andrade et al., 1999; Khobzi et al., 2008; Werb et al., 2018). The participants in this study provide specific examples of areas for improvement, ranging from recovery needs such as locally-available treatment services and clinics to general community needs such as locations for youth or family activities and grocery stores. The participants connect the economic and structural decline in their community, a continuing issue in many Appalachian and non-urban communities, with the increase of opioid use, through the lack of employment opportunities, increasing boredom, and as a coping mechanism for community-level social depression. This identified pathway suggests the need for broad, community-level interventions and speaks directly to the complex way in which community influences interact with and directly affect individual predictors of use.

This study has select limitations worth noting. First, this qualitative exploration only captures the perceptions of residents of one small town in Appalachian PA and may not reflect experiences in other parts of Appalachia or non-urban areas. Additionally, it includes perspectives from 20 stakeholders and may not broadly represent all individuals in the community and may contain selection bias despite attempts to recruit a members from a variety of key groups, including community leaders and residents who current use or have a history of use. While eight of our 20 participants shared a history of personal opioid use, we likely have not captured the full breadth of experiences of use in this or similar communities. However, it is possible participants did not disclose personal opioid use in response to our general question about their connection to the opioid epidemic; the study focus was on perceptions of use within the community rather than personal use. The lack of demographic data from our participants also limits our ability to assess if we captured a variety of perspectives across race, sex, age, or income. The methods also included a one-time interview and did not include allow for follow-up or additional investigation with participants. Through the inclusion of providers and community leaders, this broad exploration could be perceived as inadvertently perpetuating certain stigmatizing perspectives associated with opioid use. Nonetheless, such challenges often exist in exploratory, qualitative research, and a strength of our design includes using spatial analyses to select a case community among those with the greatest predicted probabilities of epidemic outbreak. Our inclusion of a variety of community perspectives, including providers, leaders, and those with a history of opioid user strengthens our ability to uncover the range of community attitudes and awareness of opioid use. Our results provide valuable insights into the drivers of the opioid epidemic in this region and suggests avenues for future research and practice activities.

While our results describe a variety of challenges faced by individuals in this community with high opioid use, the participants also clearly describe a desire for positive social support, activity and social locations and community resources, and increased community engagement on issues affecting residents of their community. In addition to addressing the existing deficits, positive and asset-building suggestions for how interventions can improve the lives of these individuals are needed. These participants‟ experiences serve as a call-to-action for those who seek ways to fulfill these community needs. Furthermore, a better understanding of the ways in which non-urban communities with economic disadvantage interact with the opioid crisis differently than those in more urban areas will be essential to designing tailored interventions. While this exploration of factors only includes those found in one small town in Pennsylvania, the results suggest that including measures of structural deprivation, acceptance and/or denial of the opioid epidemic, community engagement and development, social support, and social depression may be key to include in future studies.

Conclusion

Overall, these results highlight the importance of better understanding the complex relationships between the multi-level, contextual factors driving opioid use and overdose. While needed in all communities, this is of particular importance for lesser-studied non-urban environments, where we need to understand how these social interactions, coping strategies, and structural disadvantage connect to drivers use of opioid use. This article sets the stage for public health researchers to further utilize qualitative, community engaged, and mixed method approaches to inform future quantitative analyses of opioid use and overdose patterns. These approaches can uncover key risk factors specific to non-urban environments which to-date have not received much research attention, including areas within Appalachia. These results also support addressing the opioid epidemic in the Appalachian region by leveraging existing assets to increase community-based strategies and to strengthen the ability of communities to implement systems-wide approaches (Beatty & Hale, 2019).

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant # R03 DA043373.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest: None

References

- [Town] Bicentennial Committee. (1976). It Happened Here. Retrieved from http://www.[town]developmentcorp.org/history.htm

- Andrade X, Sifaneck S, & Neaigus A (1999). Dope Sniffers in New York City: An Ethnography of Heroin Markets and Patterns of Use. Journal of Drug Issues, 29(2), 271–298. [Google Scholar]

- Appalachian Regional Commission. (2013). Education – High School and College Completion Rates, 2009–2013. Retrieved from https://www.arc.gov/reports/custom_report.asp?REPORT_ID=61

- Appalachian Regional Commission. (2014a). Personal Income Rates, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.arc.gov/reports/custom_report.asp?REPORT_ID=63

- Appalachian Regional Commission. (2014b). Poverty Rates, 2010–2014. Retrieved from https://www.arc.gov/reports/custom_report.asp?REPORT_ID=64

- Appalachian Regional Commission. (2014c). Unemployment Rates, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.arc.gov/reports/custom_report.asp?REPORT_ID=23

- Appalachian Regional Commission. (2017). Health Care Systems; Creating a Culture of Health in Appalachia: Disparities and Bright Spots. Retrieved from https://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/Health_Disparities_in_Appalachia_Health_Care_Systems_Domain.pdf

- Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, & Beyrer C (2013). Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health, 13, 482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty K, & Hale N (2019). Health Disparities Related to Opioid Misuse in Appalachia. Retrieved from https://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/HealthDisparitiesRelatedtoOpioidMisuseinAppalachiaApr2019.pdf

- Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, & Jackson JS (2001). Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav, 42(2), 151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, & Deaton A (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112(49), 15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, & Deaton A (2017). Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/6_casedeaton.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cerda M, Gaidus A, Keyes KM, Ponicki W, Martins S, Galea S, & Gruenewald P (2017). Prescription opioid poisoning across urban and rural areas: identifying vulnerable groups and geographic areas. Addiction, 112(1), 103–112. doi: 10.1111/add.13543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud DH, Ibragimov U, Prood N, Young AM, & Cooper HLF (2019). Rural risk environments for hepatitis c among young adults in appalachian kentucky. Int J Drug Policy. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Gilreath TD, Aklin WM, & Brex RA (2010). Social-ecological influences on patterns of substance use among non-metropolitan high school students. Am J Community Psychol, 45(1–2), 36–48. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9289-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, & Ciccarone D (2018). Opioid Crisis: No Easy Fix to Its Social and Economic Determinants. Am J Public Health, 108(2), 182–186. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2017.304187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Agency. (2015). Analysis of Drug-Related Overdose Deaths in Pennsylvania, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.dea.gov/documents/2015/11/01/analysis-drug-related-overdose-deaths-pennsylvania-2014

- Guise A, Horyniak D, Melo J, McNeil R, & Werb D (2017). The experience of initiating injection drug use and its social context: a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Addiction, 112(12), 2098–2111. doi: 10.1111/add.13957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khobzi N, Strike C, Cavalieri W, Bright R, Myers T, Calzavara L, & Millson M (2008). A Qualitative Study on the Initiation into Injection Drug Use: Necessary and Background Processes. Addict Res Theory, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- King NB, Fraser V, Boikos C, Richardson R, & Harper S (2014). Determinants of increased opioid-related mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: a systematic review. Am J Public Health, 104(8), e32–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.301966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton SL, Haley DF, Hunter-Jones J, Ross Z, & Cooper HLF (2017). Social causation and neighborhood selection underlie associations of neighborhood factors with illicit drug-using social networks and illicit drug use among adults relocated from public housing. Soc Sci Med, 185, 81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair C, Sumetsky N, Burke JG, & Gaidus A (2018). Investigating the Social Ecological Contexts of Opioid Use Disorder and Poisoning Hospitalizations in Pennsylvania. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 79(6), 899–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean K (2016). “There’s nothing here”: Deindustrialization as risk environment for overdose. Int J Drug Policy, 29, 19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meit M, Heffernan M, Tanenbaum E, & Hoffman T (2017). Appalachian Disease of Despair. Retrieved from https://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/AppalachianDiseasesofDespairAugust2017.pdf

- NVivo. (2017). NVivo 11: Run a Coding Comparison Query. Retrieved from http://help-nv11.qsrinternational.com/desktop/procedures/run_a_coding_comparison_query.htm

- Pear VA, Ponicki WR, Gaidus A, Keyes KM, Martins SS, Fink DS, … Cerda M (2018). Urban-rural variation in the socioeconomic determinants of opioid overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend, 195, 66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council (PHC4). (2016). PHC4 Research Brief- Hospitalization for Overdose of Pain Medication and Heroin. Retrieved from http://www.phc4.org/reports/researchbriefs/overdoses/012616/docs/researchbrief_overdose2000-2014.pdf

- Quinn K, Boone L, Scheidell JD, Mateu-Gelabert P, McGorray SP, Beharie N, … Khan MR (2016). The relationships of childhood trauma and adulthood prescription pain reliever misuse and injection drug use. Drug Alcohol Depend, 169, 190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmati A, Herfeh F, & Hosseini S (2018). Effective Factors in First Drug Use Experience Among Male and Female Addicts: A Qualitative Study. Int J High Risk Behv Addict, 7(4). [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T (2002). The ‘Risk Environment’: A Framework for Understanding and Reducing Drug-Related Harm. International Journal of Drug Policy, 13, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T (2009). Risk environments and drug harms: a social science for harm reduction approach. Int J Drug Policy, 20(3), 193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigg KK, Monnat SM, & Chavez MN (2018). Opioid-related mortality in rural America: Geographic heterogeneity and intervention strategies. Int J Drug Policy, 57, 119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Conti MT, Kenney S, Anderson BJ, Flori JN, Risi MM, & Bailey GL (2017). Adverse childhood experience effects on opioid use initiation, injection drug use, and overdose among persons with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend, 179, 325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumetsky N, Burke JG, & Mair C (2019). Opioid-related diagnoses and HIV, HCV and mental disorders: using Pennsylvania hospitalisation data to assess community-level relationships over space and time. J Epidemiol Community Health. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-212551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. (2016). Poverty Thresholds for 2015 by Size of Family and Number of Related Children Under 18 years. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty.html

- United States Census Bureau. (2017). American FactFinder. Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

- United States Census Bureau. (2019). American Community Survey: Data Profiles (2011–2015 5-Year Data Profiles). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2015/

- Werb D, Bluthenthal RN, Kolla G, Strike C, Kral AH, Uuskula A, & Des Jarlais D (2018). Preventing Injection Drug use Initiation: State of the Evidence and Opportunities for the Future. J Urban Health, 95(1), 91–98. doi: 10.1007/s11524-017-0192-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright ER, Kooreman HE, Greene MS, Chambers RA, Banerjee A, & Wilson J (2014). The iatrogenic epidemic of prescription drug abuse: county-level determinants of opioid availability and abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend, 138, 209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedinak JL, Kinnard EN, Hadland SE, Green TC, Clark MA, & Marshall BD (2016). Social context and perspectives of non-medical prescription opioid use among young adults in Rhode Island: A qualitative study. Am J Addict, 25(8), 659–665. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]