Abstract

With the recent emergence of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19, healthcare facilities and personnel are expected to rapidly triage and care for patients with even the most complex medical conditions. Adults with congenital heart disease (ACHD) represent an often-intimidating group of complex cardiovascular disorders. Given that general internists and general cardiologists will often be asked to evaluate this group during the pandemic, we propose here an abbreviated triage algorithm that will assist in identifying the patient's overarching ACHD phenotype and baseline cardiac status. The strategy outlined allows for rapid triage and groups various anatomic CHD variants into overarching phenotypes, permitting care teams to quickly review key points in the management of moderate to severely complex ACHD patients.

Highlights

-

•

ACHD patients may be at increased risk of poor outcomes with COVID-19.

-

•

Rapid triage of the ACHD patient is needed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

We propose a simplified algorithm for triage and care of COVID19+ ACHD patients.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease - 2019 (COVID-19) was first recognized in Wuhan, China in December 2019. In a few short months, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has rapidly spread, resulting in a global pandemic [1]. The clinical presentation of COVID-19 typically includes: fever, cough, shortness of breath, fatigue and myalgias. Less commonly, those affected have demonstrated anosmia, sore throat, and nausea/vomiting. As a disease, COVID-19 is characterized predominantly by respiratory compromise, and in some cases evolves to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Patients with underlying cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic lung disease appear to be at higher risk for the development of severe disease with ARDS [2].

Limited data has been reported on outcomes in adults with congenital heart disease (ACHD) who contract SARS-CoV-2 and develop COVID-19 infection. Given that the most significant advances in interventional and surgical care of CHD evolved over the last 50 years, adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) as a group are younger than patients with acquired cardiovascular disease. However, ACHD patients demonstrate a higher prevalence of restrictive lung disease, acquired cardiovascular disease, and other general medical comorbidities [3,4]. Therefore, the patient with ACHD and COVID-19 may be at risk for severe disease and poor outcomes.

As a group, CHD is a heterogenous cohort, and these patients are often defined primarily by the original anatomic defect (although sometimes by the palliative procedure) and physiologic functional class [5]. In the face of the current pandemic, these patients may present to primary care providers, the emergency department, and other healthcare providers outside of their primary ACHD cardiologist. Furthermore, there is currently a lack of evidence available in COVID-19 infection in CHD patients to guide the evaluation and management of this complex group. We believe a rapid and concise triage algorithm for ACHD patients should include broad categorization of ACHD phenotype in order to ensure swift triage and care in the setting of known/suspected COVID-19. Here we propose an ACHD phenotype classification system to accurately characterize the ACHD patient with moderate-severely complex CHD. This “ACHD phenotype” will allow the non-ACHD physician evaluating a patient with known/suspected COVID-19 to rapidly recognize CHD anatomy and apply appropriate triage guidelines based upon the phenotype and baseline physiologic CHD level of compensation/decompensation. Here we review a reasonable approach to identifying ACHD phenotypes and physiologic compensation to assist in the rapid triage of ACHD patients with known/suspected COVID-19.

1.1. ACHD phenotypes

We will focus the proposed triage system on ACHD patients with moderate or severely complex lesions, as this group is usually the most troublesome to understand for those without a background in CHD. Recognizing there is often physiologic overlap between groups, we propose 5 broad “ACHD phenotypes” (Table 1 ) to include:

-

•

CHD with pulmonary arterial hypertension (CHD-PAH)

-

•

Cyanotic CHD

-

•

Single ventricle / Fontan anatomy

-

•

Right heart failure (RHF)

-

•

Systemic right ventricle (RV)

Table 1.

Characteristics of ACHD Phenotypes.

| CHD-PAH | Cyanotic CHD | Single Ventricle (Fontan) | RHF | Systemic RV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition |

|

|

|

|

|

| Examples |

|

|

|

|

|

| Key Points in Care |

|

|

|

|

|

APV: Anomalous pulmonary veins, ASD: Atrial septal defect, AVM: arteriovenous malformations, CCTGA: Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, CHD: Congenital heart disease, CVP: Central venous pressure, D-TGA: d-transposition of the great arteries, ES: Eisenmenger syndrome, HLHS: Hypoplastic left heart syndrome, IVC: Inferior vena cava, LV: Left ventricle, PAH: Pulmonary arterial hypertension, PDA: Patent ductus arteriosus, PI: Pulmonary insufficiency, PND: paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, Pulmonic stenosis: PS, PPV: Positive pressure ventilation, PS: Pulmonary stenosis, PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance, RHF: Right heart failure, RV: Right ventricle, SVC: Superior vena cava, ToF: Tetralogy of Fallot, VSD: Ventricular septal defect.

CHD-PAH. Several types of CHD may coexist with PAH, including those patients with unrepaired intracardiac shunts, significant arteriovenous malformations, and complex congenital heart disease with either a surgically placed shunt and/or arteriovenous collateral formation to augment pulmonary blood flow. The characteristics of this phenotype include: elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), RV enlargement, RV dysfunction, and chronic hypoxia. RHF often develops, and maintaining preload is important to support cardiac output.

Cyanotic CHD. Chronic hypoxia and cyanosis may result from unrepaired intracardiac (or less commonly extracardiac) shunts, intentional surgical fenestrations, baffle leaks, or from vascular collateral development (venovenous or arteriovenous with elevated PVR). Chronic hypoxia leads to multi-system disease inclusive of: secondary erythrocytosis, hyperuricemia, gout, concomitant hypercoagulability and increased bleeding risk, and end-organ dysfunction such as renal failure. It is important recognize that when a shunt or fenestration is present, right-to-left shunting may occur when cardiac output is compromised. In this scenario, the resultant hypoxia is secondary to the shunt, and not reflective of oxygen exchange problems at the parenchymal level of the lung. It is therefore important to understand the degree of hypoxia present at baseline (SpO2) before the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

Single Ventricle / Fontan Anatomy. Patients born with a single ventricle often undergo a series of surgeries that culminate in a Fontan procedure. In this physiology, deoxygenated blood empties passively to the lungs due to an absent subpulmonic ventricle. Pulmonary blood flow is dependent on adequate systemic venous pressure, and therefore so is cardiac output. Increases in intrathoracic pressure, such as from positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) ventilation, may compromise pulmonary filling. Many patients with a Fontan palliation have either intentional or anatomic shunts in addition to coronary sinus incorporation to a single atrium, all of which result in some degree of resting hypoxia, highlighting the need to understand normal resting SpO2 in this group. Late after Fontan palliation, patients may develop “Fontan Failure”, a syndrome that, to some extent, mimicks right heart failure, and may be associated with protein losing enteropathy.

Right Heart Failure. Several types of CHD are prone to develop failure of the subpulmonic ventricle and include: repaired tetralogy of Fallot, Ebstein anomaly, single ventricle / Fontan and CHD-PAH. Symptoms are similar to RHF in patients with 2-ventricle anatomy and include: fatigue, abdominal distention, poor appetite and peripheral edema. These patients may have compromised cardiac output due to dysfunction of the subpulmonic ventricle. Similar to CHD-PAH and Fontan physiology, they are preload dependent to maintain adequate cardiac output.

Systemic RV. In rare cases, the morphologic RV is positioned as the systemic ventricle (i.e. D-Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) with atrial switch or congenitally corrected-TGA), which is prone to early failure. Symptoms largely mirror those seen in left heart failure of the 2-ventricle population and include: dyspnea on exertion, pulmonary edema, peripheral edema and low cardiac output symptoms. Almost universally, systolic function of a systemic RV is not normal, and even though these patients may be compensated at baseline, critical illness may tip them into clinical heart failure.

1.2. Rapid physiologic assessment

Once the practitioner is able to identify the overarching ACHD phenotype, physiologic assessment becomes important. Essentially the goal of rapid physiologic assessment is to determine the status of CHD at baseline – compensated, early decompensation, or late decompensation. A careful review of prior history and imaging, as well documentation of baseline NYHA functional status and SpO2 is prudent. The presence of arrhythmia, residual hemodynamic lesions, and extra-cardiac abnormalities indicate a more advanced physiological stage. Recent cardiopulmonary stress and VO2 testing can help clarify objective evidence of a patient's functional status. This must, however, be interpreted with caution, as it is well known that ACHD patients exhibit lower than predicted values when compared to age matched individuals [6].

Compensated ACHD patients, regardless of physiological stage, will likely display only mild symptoms. Early decompensation should be suspected in patients with lower than usual SpO2 (>5 percentage points) or increased oxygen requirements, weight gain attributable to fluid retention (>5–8 pounds), worsening dyspnea on exertion, asymptomatic atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, or an exacerbation of chronic non-cardiac end organ complications. These patients tend to also have low reserve and in acute illness can decline rapidly and precipitously. Late decompensation is identified by the inability to oxygenate effectively without the use of non-invasive/mechanical ventilation, signs of poor perfusion from decompensated heart failure and multi-organ dysfunction as well as refractory and symptomatic arrhythmias requiring immediate pharmacological or electrical interventions.

1.3. Triage of the patient with known/suspected COVID-19

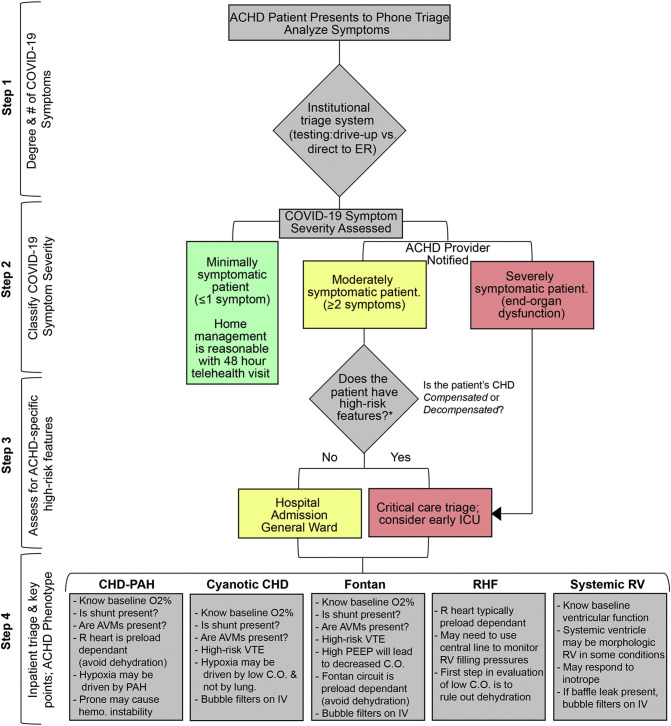

Triage of the moderate-severely complex ACHD patient with known/suspected COVID-19 relies on a multi-step process that assesses patient characteristics in the following order: 1) Degree of COVID-19-specific symptoms, 2) Classification of COVID-19 symptom severity, 3) Assessment of general ACHD-based high-risk features and 4) Inpatient triage and management-specific key points based upon the over-arching ACHD phenotype.

The first step in triage of the moderate-severely complex ACHD patient with known/suspected COVID-19 is to assess whether or not the patient has symptoms consistent with COVID-19 infection. This patient is offered COVID-19 testing at the discretion of the institution's protocol, which typically relies on an assessment of symptoms and comorbid conditions. It is important to recognize that shortage in screening resources is often what dictates whom and how initial testing is allocated.

Once the patient is suspected or known to have COVID-19, we propose stratifying the next steps based upon the degree of symptoms from the virus (minimally, moderately and severely symptomatic). We propose that the mildly symptomatic ACHD patient with ≤1 symptom is likely reasonably managed at home with appropriate telehealth follow-up within 48 h. Severely symptomatic patients with evidence of end-organ dysfunction should be admitted to the hospital (intensive care unit, ICU). In those that are moderately symptomatic with ≥2 symptoms, inpatient management is likely warranted but should be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Step 3 is focused on the assessment of the moderately symptomatic patient and centers on whether or not the patient has baseline high-risk ACHD features* (Fig. 1 ) or high-risk COVID-19 laboratory results [2]. At this step, the ACHD specialist may assist in determining if baseline ACHD features are stable (Compensated) or unstable (Decompensated). As outlined above, compensated patients typically have a stable (although often lower) SpO2, functional class and limited symptoms. Those with early decompensation may have demonstrated declines in exercise tolerance and/or symptoms in the preceding months or years. This is considered in order to determine which patients may benefit from higher levels of care beyond general ward hospital admission.

Fig. 1.

Triage algorithm, known/suspected COVID-19 in ACHD.

Proposed triage algorithm for moderate-severely complex ACHD patients with known/suspected COVID-19. Step1: Patient undergoes initial phone or in-person triage per the institutional triage guideline policy. Step 2: COVID-19 symptoms assess and patients triaged based on number of symptoms (Minimally symptomatic: <1 non-fever symptom, Moderately symptomatic: ≥ 2 symptoms or single symptom of fever, Severely symptomatic: evidence of end-organ dysfunction). Severely symptomatic patients are triaged to inpatient with consideration of early intensive care management. Step 3: Moderately symptomatic patients are assessed for high-risk ACHD features (*Fontan physiology, Cyanotic CHD, O2 < 85%, CHD with pulmonary hypertension, > Moderate systemic ventricular dysfunction, Chronic secondary organ dysfunction (i.e. pulmonary, renal, etc.), Genetic disorder with compromised immune system, Early or late baseline ACHD decompensated status). Step 4: ACHD phenotype is assessed to assist with management of lesion-specific key findings secondary to ACHD.

Step 4 is the final phase of ACHD phenotypic assessment. Recognition of the ACHD phenotype is used to help determine aspects of the patient's presentation that are normal for the type of underlying ACHD versus those that may be pathologic. Here, moderate and high-risk patients are assessed based upon their underlying phenotype to assist in determining adjunctive management strategies for CHD-specific symptoms with concurrent COVID-19 (Fig. 1, Supplemental Table 1).

1.4. Inpatient considerations: mechanical ventilation and oxygenation

The principles for intubation, oxygenation and mechanical ventilation for the COVID −19 positive ACHD patient begin with understanding the patient's baseline cardiac status with a focus on the following areas:

-

•

Oxygen saturation: Patients with right-to-left shunts may have resting hypoxia (SpO2 ~ 85–90%); those with chronic cyanosis and or Eisenmenger Syndrome may be more pronounced (SpO2 ~ 75–80%).

-

•

RHF phenotype (dilated RV with reduced RV systolic function): These patients may more easily develop hemodynamic instability with intubation.

-

•

Intracardiac Shunt: Such patients may present with worsening hypoxia due to increased right-to-left shunting that can occur due to low cardiac output (trade hypoxia for cardiac output). In this case, supporting the hemodynamic status will improve oxygenation (it is not a primary lung problem).

-

•

Cardiac Preload: Several ACHD phenotypes (discussed above) are preload dependent and poor filling (dehydration) may affect the ability to provide adequate cardiac output, particularly in the setting of intubation/mechanical ventilation.

Considering this data, mechanical ventilation support strategies for ACHD patients should mirror those patients with significant cardiovascular and pulmonary disease who develop ARDS, with the following anatomic and physiologic caveats:

-

1.

The indication for intubation should be based on knowledge of baseline SpO2, and evidence of clinical hypoxia. In patients with intracardiac shunts, low SpO2 may reflect a drop in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) or low cardiac output, rather than lung parenchymal driven hypoxia. Management in this case should focus on hemodynamic support (SVR and cardiac output).

-

2.

If the patient has underlying RHF or PAH, consideration of pre-intubation central venous access is reasonable. This permits real-time monitoring of cardiac preload (goal CVP ~ 10–15 mmHg may be reasonable). In RHF phenotypes, empiric volume resuscitation prior to intubation may be required.

-

3.

In patients with RHF phenotypes and/or PAH, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) may be poorly tolerated, as it will limit pulmonary filling.

-

4.

In the CHD patient with PAH, prone ventilation may contribute to hemodynamic compromise, and therefore should be monitored closely as this maneuver is initiated.

1.5. Inpatient considerations: cardiogenic shock

The goals of treatment in cardiogenic shock are to maintain adequate end organ perfusion and oxygenation. The physiology of the ACHD patient requiring supportive therapy with mechanical ventilation and vasoactive medications may be altered unfavorably in more complex forms of CHD. Invasive hemodynamic monitoring is critical but may be challenging given anatomical constraints. Nonetheless, in consult with specialized ACHD teams, usually both arterial and venous monitoring line positions may be identified. While the use of inotropic agents in patients with ventricular dysfunction or PAH and vasoactive medications in sepsis is crucial, they must be used with caution as the combination of systemic and/or pulmonary vasoconstriction and increased intra-thoracic pressures due to mechanical ventilation can lead to a vicious cycle of worsening cardiac decompensation.

Early multidisciplinary involvement including ACHD, congenital cardiac surgery, and heart failure and transplant teams is essential to help guide complex care and planning for advanced therapies when caring for critically ill ACHD patients. Advanced therapies utilized for severe COVID-19 cases such as extra corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) should be offered for standard indications with multidisciplinary consensus.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.06.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L., Wei Y., Li H., Wu X., Xu J., Tu S., Zhang Y., Chen H., Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginde S., Bartz P.J., Hill G.D., Danduran M.J., Biller J., Sowinski J., Tweddell J.S., Earing M.G. Restrictive lung disease is an independent predictor of exercise intolerance in the adult with congenital heart disease. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2013;8:246–254. doi: 10.1111/chd.12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuijpers J.M., Vaartjes I., Bokma J.P., van Melle J.P., Sieswerda G.T., Konings T.C., Boo M. Bakker-de, Bilt I. vander, Voogel B., Zwinderman A.H., Mulder B.J.M., Bouma B.J. Risk of coronary artery disease in adults with congenital heart disease: A comparison with the general population. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020;304:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.11.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stout K.K., Daniels C.J., Aboulhosn J.A., Bozkurt B., Broberg C.S., Colman J.M., Crumb S.R., Dearani J.A., Fuller S., Gurvitz M., Khairy P., Landzberg M.J., Saidi A., Valente A.M., Van Hare G.F. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019;73:1494–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diller G.P., Dimopolous K., Okonko D., Li W., Babu-Narayan S.V., Broberg C.S., Johansson B., Bouzas B., Mullen M.J., Poole-Wilson P.A., Francis D.P., Gatzoulis M.A. Exercise intolerance in adult congenital heart disease: comparative severity correlates and prognostic implication. Circulation. 2005;112:828–835. doi: 10.1161/Circulationaha.104.529800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material