Abstract

The stethoscope has long been at the center of patient care, as well as a symbol of the physician–patient relationship. While advancements in other diagnostic modalities have allowed for more efficient and accurate diagnosis, the stethoscope has evolved in parallel to address the needs of the modern era of medicine. These advancements include sound visualization, ambient noise reduction/cancellation, Bluetooth (Bluetooth SIG Inc, Kirkland, Wash) transmission, and computer algorithm diagnostic support. However, despite these advancements, the ever-changing climate of infection prevention, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, has led many to question the stethoscope as a vector for infectious diseases. Stethoscopes have been reported to harbor bacteria with contamination levels comparable with a physician's hand. Although disinfection is recommended, stethoscope hygiene compliance remains low. In addition, disinfectants may not be completely effective in eliminating microorganisms. Despite these risks, the growing technological integration with the stethoscope continues to make it a highly valuable tool. Rather than casting our valuable tool and symbol of medicine aside, we must create and implement an effective method of stethoscope hygiene to keep patients safe.

Keywords: Advancement, COVID-19, Stethoscope

Clinical Significance.

-

•

Stethoscopes are clinically valuable and integral to the doctor–patient connection.

-

•

Technological advancement will augment the utility of the stethoscope.

-

•

The stethoscope has high utility for assessment of COVID-19 patients.

-

•

Pathogen contamination in light of COVID-19 is a concern for the stethoscope.

-

•

Innovations in stethoscope hygiene will allow safe auscultation.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Background

With the COVID-19 (SARS-COV-2) pandemic warranting a thorough assessment of our infection prevention practices, it is no surprise that once again, the fate of the stethoscope has been the subject of intense debate. Some have chosen to abandon the stethoscope to avoid potential transmission of bacteria or viruses to patients. Others recognize the value it provides at the bedside. The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the stethoscope's continued relevance in light of the current changing landscape of infection prevention. In addition, we intend to establish how technological advancement may augment both the clinical utility and safety of the stethoscope while maintaining the symbol of our profession that physicians and patients alike regard as central to the human connection of medicine.

Stethoscope: More than Just an Icon

What initially began as René Laennec's (1781-1826) awkward examination of his female patient with his stethoscope prototype has now become the paradigm of the physical examination.1 In an editorial from Dr. Valentin Fuster, former Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, he describes the tremendous value that the stethoscope holds in providing rapid diagnostic and prognostic information. Dr. Fuster also discussed how the stethoscope fulfills an essential pillar of clinical medicine by enabling the physician to listen, touch, and diagnose a patient.2 This principle bears profound relevance to patient care during a pandemic. Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 are placed in isolation and separated from their loved ones—thus, the ability for a clinician to be a tangible emotional connection for them is important now more than ever.

Stethoscope technology has not changed significantly in the past 200 years, which has led to a greater focus on other modalities such as echocardiography, cardiac computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other diagnostic tools such as cardiac biomarkers.3 This conflict has been further exacerbated by the notion of handheld ultrasound supplanting the stethoscope. Despite the welcome addition to the physician's armamentarium, concerns have been raised that increased reliance on diagnostic technologies could compromise bedside manner as well as diagnostic accuracy.2 In a recent article advocating for the institution of point-of-care ultrasound in medical education, the authors expressed concern over the high rate of misdiagnoses that can occur when ultrasound is performed by an inexperienced operator. In addition, they raised concerns over the additional training that would be required to achieve competency with this significantly more anatomical assessment.4

It is the authors’ belief that an increased emphasis on point-of-care ultrasound and other technologies may overshadow the valuable information that can be derived through auscultation. For instance, the S3 heart sound is highly predictive of left ventricular dysfunction, and poses a profound prognostic impact on patients with heart failure.5 While it is clear that ultrasound can provide more anatomical information that can aid in diagnosis, the stethoscope allows the listener to hear things that might not be readily apparent in an echocardiogram, such as early pericarditis without pericardial effusion, pulmonary hypertension without detectable tricuspid regurgitation, or a pleural rub.2

The Digital Stethoscope

Recently, similar to the growth and advancement of medicine's imaging technologies, the stethoscope has also found a way to evolve its diagnostic capabilities through the advent of the digital stethoscope. Initial models integrated features such as ambient noise reduction,6 heart sound amplification,7 and Bluetooth (Bluetooth SIG Inc, Kirkland, Wash) transmission to external devices.8 , 9 The ability to record and transmit heart sounds can be useful in patients who are in isolation precautions, where multiple providers can listen to the heart and lung auscultation with only a single individual needing to enter the patient room. Once outside the room, the recorded breath sounds, heart sounds, and murmurs can be played for the entire health care team. The ability to record and transmit heart sounds can also provide utility for telemedicine, where auscultatory information can be assessed by providers remotely.

One of the main criticisms of the stethoscope is its strong reliance on subjective interpretation. However, developments in machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) technology have allowed for analysis of complex data, such as heart sounds, murmurs, and abnormal heart rhythms. These technologies use novel algorithmic and statistical methods to allow computers to “learn” from the given data.10 Applications of ML and AI have been met with success; one study implementing an ML algorithm reported >90% accuracy in detecting aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, mitral stenosis, and mitral regurgitation.11 Another study using an artificial neural network program (another modality of AI) reported a sensitivity and specificity of 100% for screening heart murmurs in children.12

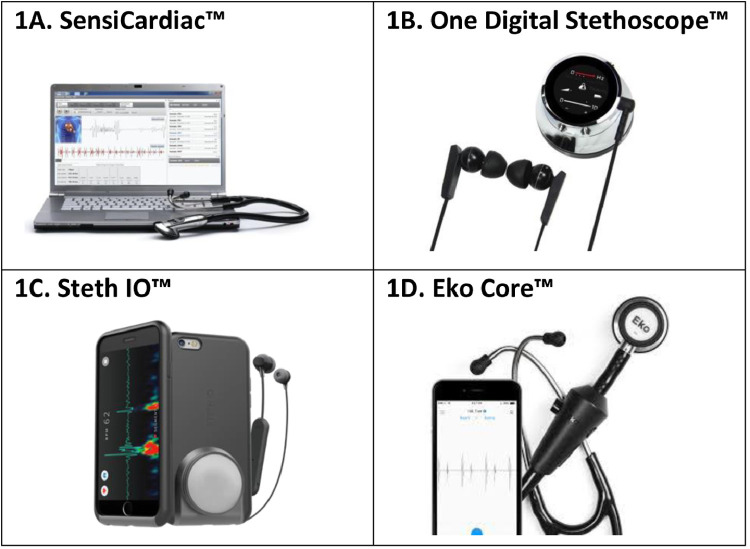

Smartphones have the potential to integrate these new stethoscope technologies and incorporate them into our daily clinical practice. Current smartphone applications that can visualize and record heart sounds have broad implications for the future of auscultation. One of the first smartphone medical applications was iStethoscope Pro (Peter Bentley, London, UK), which is capable of recording heart sounds using the internal microphone while the phone is placed in direct contact with the skin. It can then provide a spectrograph visualization of the heart sounds on the application interface.13 However, these initial applications often lacked the capability to identify the S1 and S2 heart sounds and determine key diagnostic information, such as heart rate or the presence of heart sound abnormalities. Developments have been made to improve the analytical capabilities of these heart sound applications. The SensiCardiac (Stone Three Healthcare, Cape Town, South Africa) mobile application is one of the current heart sound analysis applications, and claims to objectively distinguish between pathological and innocent murmurs with a sensitivity and specificity above 80%14 (Figure 1 14, 15, 16, 17).

Figure 1.

Recent advancements in stethoscope technology. Recent developments in stethoscope technology have included phonographic visualization, Bluetooth transmission, ambient noise reduction and heart sound amplification, and automated diagnostic support using machine learning, and artificial intelligence algorithms. The integration of computer algorithm support with smartphones has the potential to increase the portability and accessibility of these technologies.14, 15, 16, 17 All images were retrieved with permission from the developers (Stone Three Healthcare, Cape Town, South Africa; Thinklabs, Centennial, Colo; Steth IO, Bothell, Wash; Eko Devices, Berkeley, Calif).

Various smartphone accessories have been developed to combine the portability of mobile phones with the capabilities of digital stethoscope technology. For example, Thinklabs (Thinklabs, Centennial, Colo) developed the One Digital Stethoscope, which is a digital chest-piece that connects with any headphone or listening device. This device can connect directly to a smartphone or tablet to get a direct phonocardiogram reading, which can be sent to other devices.15 The Steth IO (Steth IO, Bothell, Wash) is a 3-dimensional printed smartphone case with an attached chest piece-like receiver that can transmit information directly to a mobile app16 (Figure 1).

In early 2020, the Eko Core Digital Stethoscope (Eko Devices, Berkeley, Calif) became one of the first digital stethoscopes that integrated artificial intelligence diagnostic support (Figure 1). The developers claim that the Eko Core can detect atrial fibrillation with a sensitivity and specificity of 99% and 97%, respectively, and heart murmurs with a sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 87%, respectively.17 In addition, developers collaborated with researchers at the Mayo Clinic to incorporate an algorithm for detection of asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, defined as an ejection fraction below 35%. The algorithm was validated in a study published in Nature Medicine, demonstrating a sensitivity and specificity of 86.3% and 85.7%, respectively.18 The Eko Core is currently being used at over 4000 hospitals, clinics, and medical schools,17 showing great promise for the rapid diagnosis of heart dysfunction and heart failure at the bedside using the stethoscope.

The Value of the Stethoscope for Diagnosing COVID-19 Patients

One of the most common clinical presentations of COVID-19 infection is multifocal pneumonia, often occurring prior to acute respiratory distress, hypoxia, and the need for mechanical ventilatory assistance.19 , 20 Pneumonia is often diagnosed with the presentation of one clinical symptom (eg, dry cough, fever, dyspnea), coarse breath sounds upon auscultation, inflammatory biomarkers, and opacification present on chest X-ray or computed tomography imaging.21 While mild cases of COVID-19 infection can often present without signs of pneumonia, current data suggest that pneumonia is an indicator for more severe cases with worse prognosis.19 Health care facilities lacking in available imaging or biomarker tests might rely significantly on clinical assessment, including the use of the stethoscope, for assessment of pneumonia in COVID-19 positive patients.

While respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation is the main signal of impending mortality, there is a growing body of literature demonstrating that underlying cardiovascular disease carries a high comorbidity for COVID-19 infection. Data from the National Health Commission of China found that 35% of COVID-19 patients had hypertension and 17% had coronary artery disease.22 Recently, a meta-analysis of 46,248 COVID-19 positive patients found that the most prevalent comorbidities were hypertension (17 ± 7%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 14%-22%), diabetes mellitus (8 ± 6%; 95% CI, 6%-11%), and cardiovascular diseases (5 ± 4%; 95% CI, 4%-7%).23 Possible explanations include cardiovascular disease being more prevalent in elderly individuals, those with an impaired immune system, elevated levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, or a predisposition of COVID-19 for patients with cardiovascular disease due to an unknown mechanism.24 Further reports have also shown evidence of myocardial injury among COVID-19 patients in addition to reports of decreased left-ventricular function and possible viral myocarditis.25 The combination of cardiovascular comorbidities and respiratory dysfunction that is characteristic of a COVID-19 infection warrants diligent auscultation with a stethoscope. However, careful cleaning of the stethoscope's membrane is essential, as it could serve as a potentially dangerous vector of infectious disease.

The “Third Hand” of the Physician

Given the role of the stethoscope as an essential clinical tool, physician's icon, and facilitating the emotional bridge between provider and patient, it is no surprise that the stethoscope is considered to be the physician's “third hand.” However, this bears relevance not only to its integral role to the physician, but also to its potential for contamination. Hand contamination, which has a clear connection to health care-associated infections, is also an independent predictor of stethoscope contamination.26 One study demonstrated that the same pathogens found on hands are likely to also be found on the stethoscope, and that stethoscope diaphragms were more contaminated than the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the clinician's hand.27 Stethoscopes are frequently used in direct contact with a patient's skin where microbes can be present, and can be transferred from stethoscope to patient.28 Stethoscope contamination has been thoroughly reported in the literature, with several nosocomial pathogens being discovered: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Clostridioides difficile, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli (E. coli), and Klebsiella species.26 , 29, 30, 31, 32

Because the stethoscope is the “third hand” of the physician, appropriate hygiene standards are needed. Current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines designate the stethoscope as a “non-critical” medical device (ie, only in contact with intact skin, no bodily fluids), recommending that they be cleaned anywhere from after each patient interaction to once weekly using alcohol or bleach-based disinfectant.33 Given the potential for viruses, including COVID-19,34 to survive on the skin and other surfaces for an extended period of time,35 these standards might not be reflective of the danger that a contaminated stethoscope might pose.

Survey-based assessments of stethoscope hygiene practices among providers have demonstrated adherence with hygiene widely ranging from 10%-80%.36, 37, 38, 39 However, recall and social desirability biases might serve as significant confounders to this data.40 , 41 Direct observational studies have been less common—one study found stethoscope hygiene rates across different health care providers to be 13%-24%.42 Another study performed in the emergency department reported a stethoscope hygiene rate of 11.3% using conventional means, and documented unconventional practices such as putting a glove over the stethoscope (13%) and using water/hand towel to clean the stethoscope (4.3%).43 These practices suggest that while providers are aware of the risk associated with contaminated stethoscopes, they are either unaware of proper cleaning methods or are purposefully opting for a self-devised method. Reasons cited by providers for neglecting to perform stethoscope hygiene have included lack of time, forgetfulness, or lack of access to cleaning supplies.44

During times of increased concern about contamination and spread of infections, physicians may opt to forgo their stethoscopes due to a lack of clear guidance on cleaning, lack of access to proper hygiene materials, or inconvenience with current personal protective equipment guidelines. Current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines on personal protective equipment for health care workers in contact with COVID-19 patients recommend use of a respirator (N95 mask if not available), gown, gloves, and eye protection.45 This equipment can be viewed as an impediment to stethoscope usage, as it can be difficult to manage the earpieces and tubing around forms of facial/eye protection (eg, face shield); this can further discourage providers from using their stethoscope and neglect the valuable information provided by lung and heart auscultation. Rather than forgoing a tool that might be useful in the prognostication of infected patients with cardiopulmonary abnormalities, it is important that novel hygienic and technological interventions be investigated to allow safe usage of the stethoscope.

Finding a Solution for Stethoscope Hygiene

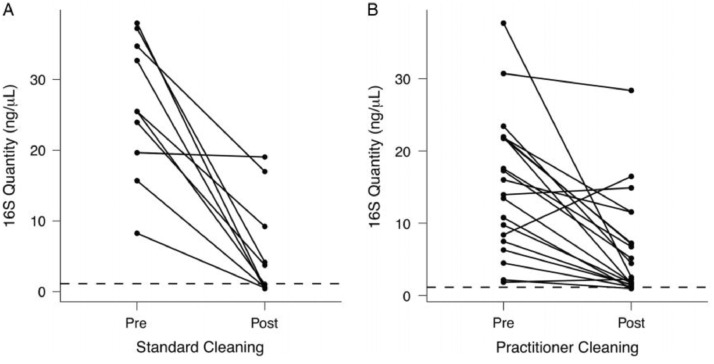

Educational interventions aiming to improve stethoscope hygiene have been implemented and met with mixed success. One study demonstrated successful reduction in stethoscope contamination rates (44.2% to 11.4%; P < .001);46 however, another demonstrated no change (0% to 0%).47 Furthermore, there is significant variability in stethoscope cleaning practices.48 A recent study performed a molecular analysis of stethoscope contamination and compared contamination levels before and after cleaning either by a standard procedure or at the physician's discretion. Although there was a significant reduction in bacterial colony counts in both groups, variable contamination was still present that could potentially pose a risk of transmission (Figure 2 48).

Figure 2.

Quantification of bacterial contamination on practitioner stethoscopes before and after cleaning. Knecht et al48 performed a molecular analysis of provider stethoscope contamination before and after either standard cleaning with hydrogen peroxide, or cleaning according to provider preference. The dashed line represents the mean bacterial contamination present on clean stethoscopes. In the standard cleaning group, 5/10 stethoscopes fell below the clean line. In the practitioner cleaning group, 2/10 stethoscopes fell below the clean line. Both groups demonstrated a significant, but not complete, reduction in contamination (P = .00174). Figure reproduced with permission from publisher (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK).

Furthermore, this study implicates that conventional cleaning methods (eg, alcohol, bleach, hydrogen peroxide) might not be completely effective in eliminating stethoscope contamination.48 These methods also present the additional risk of propagating resistant pathogens, including alcohol-resistant bacteria. One study found that Enterococcus faecium, commonly associated with nosocomial infections49 isolated from clinical cultures in 2015 was 10-fold more resistant to alcohol than previous isolates dating back to 1997.50 Single-patient stethoscopes commonly used in the intensive care unit have attempted to supplant the need for using a personal stethoscope. However, the poor quality of these stethoscopes could either lead to disuse or compromise the identification of important auscultatory findings.51 Furthermore, contamination of single-patient stethoscopes with multi-drug-resistant bacteria in the intensive care unit has been reported. One study found pathogenic contamination with MRSA on the diaphragm and ear pieces of single-use stethoscopes.52 Therefore, single-patient stethoscopes also present a significant cross-contamination risk for clinicians sharing the bedside stethoscope. It is important that we consider other modalities of stethoscope hygiene that keep both patients and clinicians safe.

Technological advancement for stethoscope hygiene might provide a safe and efficient solution that will make auscultation safe and circumvent the barriers to hygiene implementation.44 One study investigated the use of an ultraviolet-light emitting diode device that would be placed on the stethoscope diaphragm in between patient encounters, reporting an 87.5% (P < .01) reduction in colony counts after 1 minute of exposure.53 Another study tested stethoscopes made with an antimicrobial copper alloy and found significantly fewer colony-forming units than on conventional stethoscopes.54

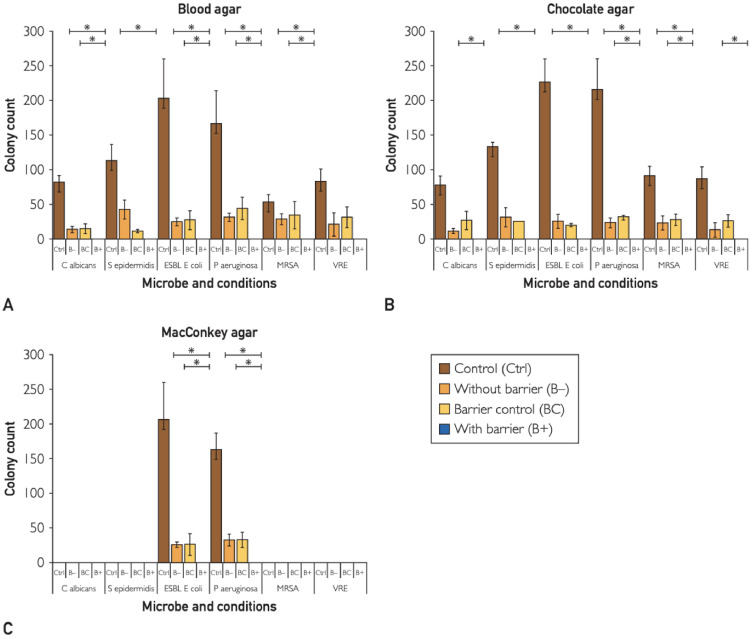

A promising sector of stethoscope hygiene is disposable covers, which offer protection to patients in the same manner as other barrier precautions such as gloves, gowns, shoe covers, etc. One study conducted a microbiological assessment with the use of single-use aseptic diaphragm barriers in preventing the transmission of several common hospital-associated pathogens, including MRSA, VRE, and E. coli. The study found zero growth of either clinical strain pathogens (P < .05) or human-sample-derived pathogens (P < .05) from stethoscopes with the diaphragm barrier (Figure 3 ).55

Figure 3.

Single-use stethoscope diaphragm covers prevent transmission of pathogenic bacteria. Vasudevan et al55 tested the efficacy of aseptic diaphragm barriers for preventing the transmission of several known pathogens: Candida albicans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, extended-spectrum b-lactamase Escherichia Coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE). Contaminated stethoscopes that had the barrier applied (B+) demonstrated no transmission of bacteria, determined by quantitative ESwab of the diaphragm surface after inoculation. Figure reproduced with permission from publisher (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Developers of this barrier (AseptiScope, San Diego, Calif) intend to integrate them with a touch-free dispenser system, similar to automatic hand-sanitizer dispensers that are ubiquitous in health care settings, to allow simple and quick application without introducing hand contamination (Figure 4 ).56

Figure 4.

Stethoscope diaphragm cover and dispensing device. Aseptic barriers provide a physical barrier to prevent the transmission from stethoscope to patient while preventing the propagation of resistant pathogens. A touch-free dispensing system will reduce the likelihood of transmission from the provider's hands or other surfaces.56 Images obtained and used with permission from the developer (AseptiScope, San Diego, Calif).

A recent paper commented on the use of stethoscopes for COVID-19 patients, stating that one of the main concerns for stethoscope usage is the lack of a specific barrier to prevent contamination and subsequent transmission to other patients.57 Perhaps a single-use diaphragm barrier system could be a viable solution to this concern and promote the safety of stethoscope usage. Similarly, this could be argued for usage in patients with infection or colonization with multi-drug-resistant organisms.

Conclusion

The stethoscope maintains its utility and relevance as a rapid bedside tool capable of gathering important diagnostic information noninvasively while maintaining the all-important physician–patient bond. Advances in stethoscope technology will improve the auscultatory capabilities of health care workers and allow less contact with patients in transmission-based precautions. It is important that providers recognize that challenges to using the stethoscope hygienically do not mean that it should simply be cast aside. Rather, physicians who are grappling with the difficulty of keeping patients safe during infectious diseases epidemics should seek to innovate and implement novel solutions for stethoscope hygiene. The physician's priority should be to maintain the highest standard of care for their patients while preserving the human connection that is foundational to the doctor–patient relationship. Patients in the modern era need not only our knowledge of medicine, but also our human connection, and the stethoscope will continue to embody the integration of those 2 facets of medicine.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of Interest: RSV, YH, FJT, BC, SMM, and RG have no conflicts to disclose. SSD: Consultant and speakers bureau: Merck; Investigator for Merck, Gilead, Ansun, Chimerix, Takeda/Shire; Advisory board: Merck, Janssen, Aseptiscope. ASM: Founder and the Chief Clinical Officer for AseptiScope Inc.

Authorship: All authors participated in the writing and editing of this manuscript and agreed upon its submission for publication.

References

- 1.Roguin A. Rene theophile hyacinthe laënnec (1781-1826): the man behind the stethoscope. Clin Med Res. 2006;4(3):230–235. doi: 10.3121/cmr.4.3.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuster V. The stethoscope's prognosis very much alive and very necessary. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9):1118–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow SL, Maisel AS, Anand I, et al. Role of biomarkers for the prevention, assessment, and management of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(22):e1054-e1091. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Solomon SD, Saldana F. Point-of-care ultrasound in medical education–stop listening and look. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1083–1085. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1311944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drazner MH, Rame JE, Stevenson LW, Dries DL. Prognostic importance of elevated jugular venous pressure and a third heart sound in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):574–581. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao CT, Maneetien N, Wang CJ. 2012 35th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing, TSP 2012 - Proceedings. 2012. On the construction of an electronic stethoscope with real-time heart sound de-noising feature.http://faculty.stust.edu.tw/~tang/project/paper/2012_TSP/0710.pdf Available at. Accessed June 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontaine E, Coste S, Poyat C. In-flight auscultation during medical air evacuation: comparison between traditional and amplified stethoscopes. Air Med J. 2014;345(8):574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung K, Zhang YT. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology - Proceedings. 2002. Usage of BluetoothTM in wireless sensors for tele-healthcare. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chien JRC, Tai CC. Conference Proceeding - IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control. 2004. The implementation of a bluetooth-based wireless phonocardio-diagnosis system. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samuel AL. Some studies in machine learning using the game of checkers. IBM J Res Dev. 2000;44(1.2):206–226. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maglogiannis I, Loukis E, Zafiropoulos E, Stasis A. Support Vectors Machine-based identification of heart valve diseases using heart sounds. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2009;95(1):47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeGroff CG, Bhatikar S, Hertzberg J, Shandas R, Valdes-Cruz L, Mahajan RL. Artificial neural network - Based method of screening heart murmurs in children. Circulation. 2001;103(22):2711–2716. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.22.2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentley PJ. Vol. 1256. 2015. IStethoscope: a demonstration of the use of mobile devices for auscultation; pp. 293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SensiCardiac. Home page. Available at: https://sensicardiac.com/. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 15.Thinklabs. One digital stethoscope. Available at: https://www.thinklabs.com/. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 16.Steth IO. Home page. Available at: https://stethio.com/. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 17.Eko Core Stethoscope. Home page. Available at: https://www.ekohealth.com/. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 18.Attia ZI, Kapa S, Lopez-Jimenez F. Screening for cardiac contractile dysfunction using an artificial intelligence–enabled electrocardiogram. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):70–74. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID‐19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):568–576. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng Z, Lu Y, Cao Q. Clinical features and chest CT manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a single-center study in Shanghai, China. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215(1):121–126. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society Consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27–S72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(5):259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141(20):1648–1655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu H, Ma F, Wei X, Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis saved with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J. 2020 Mar 16 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa190. [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tschopp C, Schneider A, Longtin Y, Renzi G, Schrenzel J, Pittet D. Predictors of Heavy Stethoscope Contamination Following a Physical Examination. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(6):673–679. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longtin Y, Schneider A, Tschopp C. Contamination of stethoscopes and physicians’ hands after a physical examination. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(3):291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marinella MA, Pierson C, Chenoweth C. The stethoscope: a potential source of nosocomial infection? Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(7):786–790. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.7.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerken A, Cavanagh S, Winner HI. Infection hazard from stethoscopes in hospital. Lancet Infect Dis. 1972;299(7762):1214–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)90928-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangi RJ, Andriole VT. Contaminated stethoscopes: a potential source of nosocomial infections. Yale J Biol Med. 1972;45(6):600–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Flaherty N, Fenelon L. The stethoscope and healthcare-associated infection: a snake in the grass or innocent bystander? J Hosp Infect. 2015;91(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeyakumari D, Nagajothi S, Praveen Kumar R, Ilayaperumal G, Vigneshwaran S. Bacterial colonization of stethoscope used in the tertiary care teaching hospital: a potential source of nosocomial infection. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5(1):142–145. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rutala WA, Weber DJ. Disinfection and sterilization in health care facilities: what clinicians need to know. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(5):702–709. doi: 10.1086/423182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bean B, Moore BM, Sterner B, Peterson LR, Gerding DN, Balfour HH. Survival of influenza viruses on environmental surfaces. J Infect Dis. 1982;146(1):47–51. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fenelon L, Holcroft L, Waters N. Contamination of stethoscopes with MRSA and current disinfection practices. J Hosp Infect. 2009;71(4):376–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones JS, Hoerle D, Riekse R. Stethoscopes: a potential vector of infection. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(3):296–299. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madar R, Novakova E, Baska T. The role of non-critical health-care tools in the transmission of nosocomial infections. Bratisl lekárske List. 2005;106(11):348–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breathnach aS, Jenkins DR, Pedler SJ. Stethoscopes as possible vectors of infection by staphylococci. BMJ Br Med J. 1992;305(6868):1573–1574. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6868.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Lomas J, Ross-Degnan D. Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. Int J Qual Heal Care. 1999;11(3):187–192. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/11.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211–217. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S104807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boulée D, Kalra S, Haddock A, Johnson TD, Peacock WF. Contemporary stethoscope cleaning practices: what we haven't learned in 150 years. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47(3):238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vasudevan RS, Mojaver S, Chang KW, Maisel AS, Frank Peacock W, Chowdhury P. Observation of stethoscope sanitation practices in an emergency department setting. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47(3):234–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muniz J, Sethi RKV, Zaghi J, Ziniel SI, Sandora TJ. Predictors of stethoscope disinfection among pediatric health care providers. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(10):922–925. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) or persons under investigation for COVID-19 in healthcare settings. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/86043. Accessed June 27, 2020.

- 46.Claire Grecia S, Malanyaon O, Aguirre C. The effect of an educational intervention on the contamination rates of stethoscopes and on the knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding the stethoscope use of healthcare providers in a tertiary care hospital*. Philipp J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;37(2):20–33. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holleck JL, Merchant N, Lin S, Gupta S. Can education influence stethoscope hygiene. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(7):811–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knecht VR, Mcginniss JE, Shankar HM, et al. Molecular analysis of bacterial contamination on stethoscopes in an intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Cetinkaya Y, Falk P, Mayhall CG. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(4):686–707. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.686-707.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pidot SJ, Gao W, Buultjens AH, et al. Increasing tolerance of hospital Enterococcus faecium to handwash alcohols. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(452):eaar6115. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Khasawneh F, Mehmood M, Abugrara H, Stewart J. Comparing the auscultatory accuracy of health care professionals using three different brands of stethoscopes on a simulator. Med Devices (Auckl) 2014;7:273–281. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S67784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whittington AM, Whitlow G, Hewson D, Thomas C, Brett SJ. Bacterial contamination of stethoscopes on the intensive care unit. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(6):620–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Messina G, Burgassi S, Messina D, Montagnani V, Cevenini G. A new UV-LED device for automatic disinfection of stethoscope membranes. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(10):e61–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmidt MG, Tuuri RE, Dharsee A. Antimicrobial copper alloys decreased bacteria on stethoscope surfaces. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(6):642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vasudevan RS, Shin JH, Chopyk J. Aseptic barriers allow a clean contact for contaminated stethoscope diaphragms. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2020;4(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.AseptiScope. Home page. Available at: https://aseptiscope.com/. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 57.Buonsenso D, Pata D, Chiaretti A. COVID-19 outbreak: less stethoscope, more ultrasound. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):e27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30120-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]