Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 has caused the COVID-19 pandemic. There is an urgent need for physiological models to study SARS-CoV-2 infection using human disease-relevant cells. COVID-19 pathophysiology includes respiratory failure but involves other organ systems including gut, liver, heart, and pancreas. We present an experimental platform comprised of cell and organoid derivatives from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). A Spike-enabled pseudo-entry virus infects pancreatic endocrine cells, liver organoids, cardiomyocytes, and dopaminergic neurons. Recent clinical studies show a strong association with COVID-19 and diabetes. We find that human pancreatic beta cells and liver organoids are highly permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection, further validated using adult primary human islets and adult hepatocyte and cholangiocyte organoids. SARS-CoV-2 infection caused striking expression of chemokines, as also seen in primary human COVID-19 pulmonary autopsy samples. hPSC-derived cells/organoids provide valuable models for understanding the cellular responses of human tissues to SARS-CoV-2 infection and for disease modeling of COVID-19.

Keywords: human pluripotent stem cells, SARS-CoV-2, pancreatic endocrine cells, alpha cells, beta cells, liver organoids

Graphical Abstract

Yang et al. show that hPSC-derived cells and organoids provide valuable models to study SARS-CoV-2 tropism and to model COVID-19. They find that hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells and human adult hepatocyte and cholangiocyte organoids are permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Introduction

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Respiratory failure is the most common mortality outcome in COVID-19 patients, yet serious and even fatal manifestations are seen across multiple organ systems, including the brain (Helms et al., 2020; Pleasure et al., 2020) and gastrointestinal tract (Goyal et al., 2020). In one retrospective study of more than 400 COVID-19 patients, nearly 20% had suffered in-hospital cardiac injury, which was a significant independent risk factor for mortality (Shi et al., 2020). Nearly 25% of patients have gastrointestinal manifestations including anorexia, diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, and these symptoms are associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes (Pan et al., 2020). A recent clinical study among 7,300 COVID-19 patients also showed a strong correlation between poor COVID-19 outcomes and type 2 diabetes (Zhu et al., 2020). Recent clinical studies suggest that diabetes is not only a risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease, but also that SARS-CoV-2 infection can induce new-onset diabetes (Bornstein et al., 2020).

Currently, there are no vaccines or effective treatment options for COVID-19 due to limited knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 viral biology. Most current studies are based on clinical data, immortalized cell lines, or transgenic animals that express the human SARS viral entry receptor, ACE2. Unfortunately, these in vitro (e.g., African green monkey Vero cells or human cancer cell lines) and in vivo (e.g., mice engineered to express ACE2) models are sufficiently distinct from human biology that they are unlikely to capture key aspects of viral infection and virus-host interactions. Several human cancer lines, including A549, Calu3, HFL (lung adenocarcinoma), Caco2 (colorectal adenocarcinoma), Huh7 (hepatocellular adenocarcinoma), HeLa (cervical adenocarcinoma), 293T (embryonic kidney), U251 (glioblastoma), and RD (rhabdomyosarcoma) have been used to study SARS-CoV-2 infection and for drug evaluation (Chu et al., 2020; Hoffmann et al., 2020; Ou et al., 2020; Shang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). However, many human organs and tissues contain multiple cell types and ACE2, the putative receptor of SARS-CoV-2, is heterogeneously expressed in different cell types. Thus, using cancer cell lines might fail to appreciate the different cell types affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, most of these human cancer cell lines carry tumor-associated mutations, such as P53 mutations. P53 has been shown to regulate SARS-CoV replication, which raises concern for how these cancer cell lines recapitulate the viral biology of SARS-CoV-2 in normal non-transformed cells (Ma-Lauer et al., 2016). Moreover, certain cell lines (such as Huh7.5) have mutations in genes controlling the innate immune response (a known defect in RIG-I) which may obscure antiviral responses and the subsequent viral life cycle. As these cells are all cancer cell lines, they have maintained their ability to proliferate and often are unpolarized which could impact several components of viral infection. Taken together, it seems likely that these differences from primary cells and tissues will impact their ability to model SARS-CoV-2 infection. As a consequence, there is an urgent need to create models to study SARS-CoV-2 biology using human disease-relevant cells and tissues. A human cell-based platform to study viral tropism would be a first step toward defining cell types permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection and for modeling COVID-19 disease across multiple organ systems.

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), can be used to derive functional human cells/tissues/organoids for modeling human disease and drug discovery, including for infectious diseases. For example, hPSC-derived neuronal progenitor cells (hNPCs) and brain organoids were used to study the impact of Zika virus (ZIKV) on human brain development and the mechanistic link between ZIKV infection and microcephaly, as reviewed (Wen et al., 2017). hPSC-derived hNPCs were used to screen for anti-ZIKV drugs and identified emricasan as a pan-caspase inhibitor that protects hNPCs, in addition to cyclin-dependent kinases and niclosamide that inhibit ZIKV replication (Xu et al., 2016). Similarly, we performed a high content screen and identified an anti-ZIKV compound, hippeastrine hydrobromide, that suppressed viral propagation when administered to adult mice with active ZIKV infection, highlighting its therapeutic potential (Zhou et al., 2017). Here, we present a platform developed using hPSCs to generate multiple different cell and organoid derivatives representative of all three primary germ layers. We used these to systematically explore the viral tropism of SARS-CoV-2 and cellular responses to infection.

Results

Evaluation of ACE2 Expression across a Spectrum of hPSC-Derived Cells and Organoids

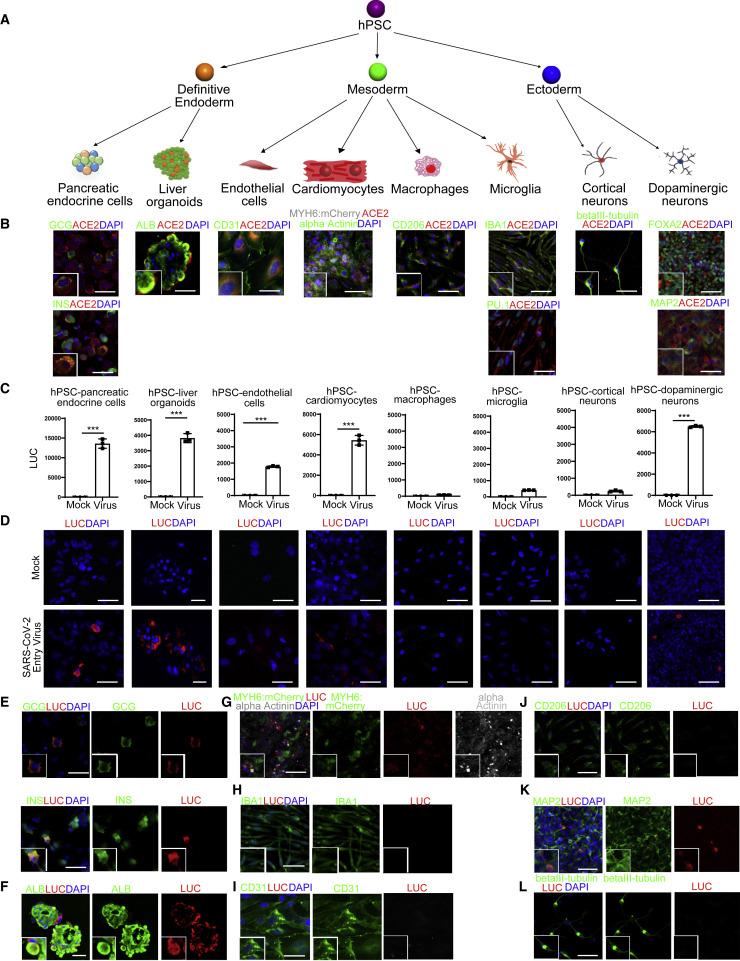

We used directed differentiation of hPSCs to generate eight distinct cell types or organoids representing lineages from all three definitive germ layers (Figure 1 A). After hPSC differentiation into definitive endoderm (DE), pancreatic and liver cells were generated. For the pancreatic lineage, DE cells were differentiated progressively into pancreatic progenitors and then directed into pancreatic endocrine lineages using a modified strategy from a previously published protocol (Zeng et al., 2016) that specifies glucagon+ (GCG+) pancreatic alpha cells, insulin+ (INS+) pancreatic beta cells, and somatostatin+ (SST+) delta cells (Figures S1A and S2A). The DE cells were otherwise induced using a modification of a previously published approach to differentiate into liver organoids, comprising mainly albumin+ (ALB+) hepatocytes (Figure S1B and S2A).

Figure 1.

ACE2 Expression and Permissiveness of hPSC-Derived Cells and Organoids to SARS-CoV-2 Pseudo-entry Virus

(A) Scheme of the hPSC differentiation to eight types of cells or organoids.

(B) Confocal imaging of hPSC-derived cells or organoids using antibodies against ACE2 and pancreatic endocrine cell markers (INS and GCG), liver cell marker (ALB), endothelial cell marker (CD31), cardiomyocyte markers (MYH6:mCherry and alpha-Actinin), macrophage marker (CD206), microglia markers (IBA1 and PU.1), cortical neuron marker (beta-III tubulin), and dopaminergic neuron markers (FOXA2 and MAP2). Scale bar represents 25 μm.

(C) Luciferase activity of eight types of hPSC-derived cells or organoids either mock or infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus at 24 hpi (MOI = 0.01). n = 3 independent biological replicates. Data were presented as mean ± STDEV. p values were calculated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D) Confocal imaging of eight types of hPSC-derived cells or organoids either mock or infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus at 24 hpi (MOI = 0.01) for luciferase staining as a measure for pseudo-entry virus infection. Scale bar represents 25 μm.

(E) Confocal imaging of hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus using antibodies against luciferase or pancreatic endocrine cell markers, INS and GCG. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

(F) Confocal imaging of hPSC-derived liver organoids infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus using antibodies against luciferase or hepatocyte cell marker, ALB. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

(G) Confocal imaging of hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus using antibodies against luciferase or cardiomyocyte markers, MYH6:mCherry and alpha-Actinin. Scale bar = 25 μm.

(H) Confocal imaging of hPSC-derived microglia infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus using antibodies against luciferase or microglia marker, IBA1. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

(I) Confocal imaging of hPSC-derived endothelial cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus using antibodies against luciferase and endothelial cell marker, CD31. Scale bar represents 25 μm.

(J) Confocal imaging of hPSC-derived macrophages infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus using antibodies against luciferase or macrophage marker, CD206. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

(K) Confocal imaging of hPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus using antibodies against luciferase or dopaminergic neuron marker, MAP2. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

(L) Confocal imaging of hPSC-derived cortical neurons infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus using antibodies against luciferase or cortical neuron marker, beta-III tubulin. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Cells committed to mesoderm fate were directed to differentiate into endothelial cells (Figure S1C), cardiomyocytes (Figure S1D), macrophages (Figure S1E), or microglia (Figure S1F). The endothelial cells stained positively with antibodies recognizing CD31 (Figure S2A). The cardiomyocytes were derived from an MYH6:mCherry hESC reporter line (Tsai et al., 2020) and more than 90% expressed mCherry and stained positively with an antibody recognizing sarcomeric α-Actinin (Figure S2A). Mesodermal cells were alternatively differentiated progressively to hematopoietic progenitor cells, monocytes, and finally either CD11b+/CD206+ macrophages or PU.1+/IBA1+ microglial cells (Figure S2A).

Cells initially induced to form ectoderm were differentiated into cortical neurons or dopaminergic neurons using previously reported protocols (Zhou et al., 2018). Day 45 cortical neurons stained positively with antibodies against beta III-tubulin, while dopaminergic neurons stained positively with antibodies recognizing the midbrain marker FOXA2 and the neuronal marker MAP2 (Figure S2A).

ACE2 is a putative receptor for SARS-CoV-2 infection (Hoffmann et al., 2020). Immunostaining was performed to examine the expression of ACE2 in the spectrum of hPSC-derived cell types. In pancreatic endocrine cells, ACE2 expression was detected readily in GCG+ alpha cells and INS+ beta cells, but not in SST+ delta cells (Figures 1B and S2B). In liver organoids, ACE2 was expressed in most ALB+ hepatocytes (Figure 1B). ACE2 was also expressed in hPSC-derived CD31+ endothelial cells, hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, microglia, CD206+ macrophages, and hPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons (Figure 1B). In contrast, ACE2 expression was detected at relatively low levels in hPSC-derived cortical neurons (Figure 1B). ACE2 expression was not detected in hPSCs (Figure S2C).

Differential Cell Type-Dependent Permissiveness to SARS-CoV-2 Pseudo-entry Virus Infection

To determine the relative permissiveness of hPSC-derived cells and organoids to SARS-CoV-2 viral entry, we used a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-based SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus, for which the backbone was provided by a VSV pseudo-typed ΔG-luciferase virus with the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein incorporated in the surface of the viral particle instead (Nie et al., 2020; Whitt, 2010). Pseudo-typed entry viruses based on either a VSV or HIV backbone have been broadly used to study SARS-CoV-2 entry (Ou et al., 2020; Shang et al., 2020) and to evaluate drug candidates (Hoffmann et al., 2020) and neutralizing antibodies (Cao et al., 2020; Lei et al., 2020; Walls et al., 2020). Each of the eight distinct hPSC-derivatives were inoculated with the SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus and at 24 h post-infection (hpi) analyzed for viral entry based on luciferase activity (Figures 1C and S2D). The results largely correlated with ACE2 expression profiles with a few exceptions. High luciferase (LUC) activity, as a readout for the efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus infection, was readily detected in hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells, liver organoids, cardiomyocytes, and dopaminergic neurons. Relatively low or no LUC levels were found for endothelial cells, microglia, macrophages, or cortical neurons. Time course experiments showed that low LUC activity was not a delayed response, as levels remained comparable at 48 h (Figure S2E). Thus, we focused on 24 hpi for remaining studies. The same cell types that showed high LUC activity stained positively with a LUC antibody (Figure 1D). In hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells, LUC expression was detected in GCG+ alpha cells and INS+ beta cells, but not in SST+ delta cells, consistent with ACE2 expression (Figure 1E and S2F). In liver organoids, LUC expression was detected in ALB+ hepatocytes (Figure 1F). LUC was also detected in sarcomeric α-Actinin+ cardiomyocytes (Figure 1G). LUC was rarely detected in IBA1+ microglial cells (Figure 1H), CD31+ endothelial cells (Figure 1I), or CD206+ macrophages (Figure 1J). Finally, LUC+ cells were detected in hPSC-derived MAP2+ and FOXA2+ dopaminergic neurons (Figures 1K and S2G), but not beta III-tubulin+ cortical neurons (Figure 1L).

Adult Human Pancreatic Alpha and Beta Cells Are Permissive to SARS-CoV-2 Pseudo-entry Virus and SARS-CoV-2 Virus Infection

Before validating permissiveness of primary human islets to SARS-CoV-2 virus, we used single-cell RNA-sequencing to examine global transcript profiles and to define cell lineages. The data were projected using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP, Figure 2 A). Nine distinct cell types were identified, including acinar, ductal, beta, alpha, mesenchymal, poly-peptide (PP), delta, endothelial, and immune cells (Figures 2B and S3A). The expression of unique marker genes, including PRSS1 (acinar cells), keratin19/KRT19 (ductal), INS (beta cells), GCG (alpha cells), COL1A1 (mesenchymal cells), PECAM1 (endothelial cells), TYROBP (immune cells), SST (delta cells), and PPY (PP cells), in each cell population confirmed the robustness of the cell type classification strategy (Figure 2B). We examined the expression profiles of two factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: the putative receptor ACE2 and the effector protease TMPRSS2 (Hoffmann et al., 2020). ACE2 and TMPRSS2 were both expressed in acinar cells, ductal cells, beta cells, alpha cells, mesenchymal cells, and endothelial cells (Figures 2C and 2D). Immunohistochemistry further validated that primary human beta cells and alpha cells express ACE2 (Figure 2E). Human primary islets were infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus (USA-WA1/2020, MOI = 0.01) and analyzed at 24 hpi by immunostaining. Both INS+ beta cells and GCG+ alpha cells (Figure 2F) stained positive for SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein.

Figure 2.

Adult Human Pancreatic Alpha and Beta Cells Express ACE2 and Are Permissive to SARS-CoV-2 Pseudo-entry Virus and SARS-CoV-2 Virus Infection

(A) UMAP of adult human islets after single-cell RNA-seq.

(B) UMAP of pancreatic cell markers, including PRSS1, KRT19, INS, GCG, COL1A1, PECAM1, TYROBP, SST, and PPY.

(C) UMAP of ACE2 and TMPRSS2.

(D) Jitter plots of ACE2 and TMPRSS2.

(E) Confocal imaging of adult human islets stained with the antibodies against ACE2, INS, or GCG. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

(F) Confocal imaging of adult human islets infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI = 0.01, 24 hpi) stained with antibodies against SARS-S, INS, or GCG. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

(G) Scheme of viral inoculation in humanized mice.

(H) Confocal imaging of human pancreatic endocrine xenografts with antibodies against ACE2, INS, or GCG. Scale bar represents 25 μm.

(I and J) Confocal imaging (I) and quantification (J) of human pancreatic endocrine xenografts against LUC, INS, or GCG, at 24 hpi of SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus (1 × 104 PFU) infection. Scale bar represents 25 μm.

n = 3 independent biological replicates. Data were presented as mean ± STDEV. p values were calculated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. ∗∗∗p < 0.001. See also Figure S3.

Humanized mice carrying human pancreatic endocrine cells in vivo provide a unique platform for modeling COVID-19. In brief, hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells were transplanted under the kidney capsule of SCID-beige mice (Figure 2G). Two months after transplantation, the organoid xenograft was removed and examined for cellular identities. Consistent with in vitro culture, ACE2 can be detected in hPSC-derived INS+ beta cells and GCG+ alpha cells (Figure 2H). Next, SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus was inoculated locally in xenografted mice (1 × 104 PFU). At 24 hpi, the xenografts were removed and analyzed by immunohistochemistry. LUC was detected in the xenografts inoculated with virus, but not in mock-infected controls. Immunohistochemistry detected LUC in INS+ beta cells and GCG+ alpha cells (Figures 2I and 2J), indicating these are both permissive to SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus infection in vivo.

SARS-CoV-2 Infection of Pancreatic Endocrine Cells Results in Robust Chemokine Induction Similar to What Is Seen in Autopsy Samples from COVID-19 Patients

To evaluate the cellular response of human pancreatic endocrine cells to SARS-CoV-2 infection, hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 (USA-WA1/2020) at increasing MOIs (MOI = 0.01, 0.05, 0.1). Viral replication 24 hpi as measured by viral subgenomic (sg) N RNA levels was detected using qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 3 A). SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein was detected in both INS+ beta cells and GCG+ alpha cells by immunofluorescence staining (Figure 3B). A substantial number of SARS-S+INS+ cells (more than 50 for each field) and SARS-S+GCG+ cells (approximately 20 for each field) were detected in SARS-CoV-2-infected conditions (Figure 3C). Transcript profiling was then performed to compare mock and SARS-CoV-2-infected cells. Alignment of transcripts with the viral genome confirmed robust viral replication in hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells (Figure 3D). Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that mock and SARS-CoV-2-infected hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cell samples cluster separately (Figure 3E). KEGG Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) comparing mock-infected with SARS-CoV-2-infected cells revealed the upregulation of pathways associated with viral infection, such as human cytomegalovirus infection, herpes simplex infection, human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection, Epstein-Barr virus infection, and hepatitis C. Interestingly, the insulin resistance pathway was also upregulated. The pathways associated with beta cell or alpha cell function, including calcium signaling pathways, glucagon signaling pathways, and metabolic pathways, were all downregulated in the virus-infected conditions (Figure 3F, Table S1). These changes could be due either to increased cell death or loss of cellular identities. To distinguish these possibilities, we stained mock or SARS-CoV-2-infected hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells with a cell apoptotic marker (CASP3) and cell type-specific markers (GCG for alpha cells and INS for beta cells). Both the percentage of CASP3+ cells in GCG+ cells and the percentage of CASP3+ cells in INS+ cells increased in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells (Figures S3B and S3C), suggesting that the changed signaling pathway profiles in SARS-CoV-2-infected hPSC-derived endocrine cells is mainly due to increased cell apoptosis. In agreement with this, genes associated with apoptosis were upregulated while genes associated with cell survival were downregulated in SARS-CoV-2-infected hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells (Figure S3D). As it is technically challenging to obtain pancreatic samples from COVID-19 patients, we compared transcript profiles from lung autopsy samples from healthy donors or COVID-19 patients and identified a robust upregulation of chemokines, including CCL2, CXCL5, and CXCL6, in the COVID-19 patient samples as has been described previously (Figure 3G; Blanco-Melo et al., 2020). These and other chemokine and cytokine transcript levels were also upregulated in SARS-CoV-2-infected pancreatic endocrine cells compared to mock infected cells (Figure 3H). Together, the data suggest that SARS-CoV-2-infected pancreatic endocrine cells show robust chemokine induction, which is similar to what is found in autopsy samples from COVID-19 patients.

Figure 3.

RNA-Seq Analysis of hPSC-Derived Endocrine Cells after SARS-CoV-2 Virus Infection Reveals the Induction of Chemokine Expression, Similar to What Is Seen in Samples from Autopsies of COVID-19 Patients

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of relative viral N sgRNA expression in hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI = 0.01, 0.05, 0.1) for 24 h. Viral N sgRNA levels were internally normalized to ACTB levels and different MOIs were compared relative to mock.

(B and C) Confocal imaging (B) and quantification (C) of SARS-CoV-2-infected (MOI = 0.01, 24 hpi) hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells stained for SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, INS, or GCG. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

(D) Read coverage of the SARS-CoV-2 genome in infected hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells (MOI = 0.01, 24 hpi). Schematic denotes the SARS-CoV-2 genome.

(E) PCA of differential gene expression from SARS-CoV-2-infected hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells compared to mock infection.

(F) KEGG gene set enrichment analysis of differential gene expression profiles from SARS-CoV-2-infected hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells compared to mock infection.

(G) Volcano plot analysis of differentially expressed genes from lung autopsies of healthy donors compared to COVID-19 patients. Individual genes denoted by gene name. Differentially expressed genes (p-adjusted value < 0.05) with a log2 (Fold Change) > 2 are indicated in red. Non-significant differentially expressed genes with a log2 (Fold Change) > 2 are indicated in green.

(H) Heatmap of chemokine transcript levels in SARS-CoV-2-infected hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cell cells compared to mock infection.

n = 3 independent biological replicates. Data were presented as mean ± SD. p values were calculated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. ∗∗∗p < 0.001. See also Table S1.

Adult Liver Hepatocyte and Cholangiocyte Organoids Are Permissive to SARS-CoV-2 Virus Infection and Show Similar Chemokine Responses for SARS-CoV-2 Infection as Seen in Autopsy Samples from COVID-19 Patients

The viral tropism analysis using hPSC-derived cells showed that hPSC-derived liver organoids are permissive to SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus infection (Figure 1F). We next used human adult hepatocyte and cholangiocyte organoids to validate this finding. Adult primary human hepatocyte organoids were infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus (MOI = 0.1). At 24 hpi, significantly increased LUC activity was detected in SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus-infected samples (Figure S4A) and LUC expression was detected in SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus-infected ALB+ hepatocytes but not mock-infected hepatocytes (Figures S4B and S4C). Consistently, LUC expression was also detected in SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus-infected CK19+ cholangiocyte organoids but not mock-infected organoids at 24 hpi (Figures S4D and S4E).

Adult primary human hepatocyte organoids were inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 (USA-WA1/2020, MOI = 0.1) and analyzed at 24 hpi. Analysis by qRT-PCR demonstrated robust SARS-CoV-2 infection as evidenced by high levels of viral sgRNA transcripts of the replicating viral RNA (Figure 4 A). This was confirmed at the protein level by immunostaining for SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein expression (Figure 4B). The percentage of SARS-S+ cells in the infected hepatocyte organoids was highly significant (Figure 4C). We were also able to generate primary human organoids comprised mostly of cholangiocytes. These organoids were also inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI = 0.1) and analyzed at 24 hpi. Analysis by qRT-PCR demonstrated robust SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure 4D), which was confirmed by immunostaining (Figure 4E), and the percentage of SARS-S+ cells in infected cholangiocyte organoids was also significant (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Adult Hepatocyte and Cholangiocyte Organoids Are Permissive to SARS-CoV-2 Virus Infection and Show a Similar Chemokine Response Compared to Autopsy Samples from COVID-19 Patients

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of relative viral N sgRNA expression in adult human hepatocyte organoids infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI = 0.1) for 24 h. Viral N sgRNA levels were internally normalized to ACTB levels and depicted relative to mock.

(B and C) Confocal imaging (B) and quantification (C) of adult human hepatocyte organoids at 24 hpi of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection (MOI = 0.1). Scale bar represents 50 μm.

(D) qRT-PCR analysis of relative viral N sgRNA expression in adult human cholangiocyte organoids infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI = 0.1) for 24 h. Viral N sgRNA levels were internally normalized to ACTB levels and depicted relative to mock.

(E and F) Confocal imaging (E) and quantification (F) of human cholangiocyte organoids at 24 hpi of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection (MOI = 0.1). Scale bar represents 50 μm.

(G) Read coverage of the SARS-CoV-2 genome in infected human hepatocyte organoids at 24 hpi of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection (MOI = 0.1). Schematic denotes the SARS-CoV-2 genome.

(H) Read coverage of the SARS-CoV-2 genome in infected adult human cholangiocyte organoids (donor 1 and donor 2) at 24 hpi of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection (MOI = 0.1). Schematic denotes the SARS-CoV-2 genome.

(I and J) PCA (I) and volcano plot (J) analysis of differential expressed genes in SARS-CoV-2-infected human hepatocyte organoids compared to mock infection. Individual genes denoted by gene name. Differentially expressed genes (p-adjusted value < 0.05) with a log2 (Fold Change) > 2 are indicated in red. Non-significant differentially expressed genes with a log2 (Fold Change) > 2 are indicated in green.

(K) KEGG gene set enrichment analysis of transcript profiles from SARS-CoV-2-infected human hepatocyte organoids compared to mock infection.

(L and M) PCA (L) and volcano plot (M) analysis of differential expressed genes in SARS-CoV-2-infected adult human cholangiocyte organoids (donor 1) compared to mock infection. Individual genes denoted by gene name.

(N) KEGG gene set enrichment analysis of transcripts from SARS-CoV-2-infected adult human cholangiocyte organoids (donor 1) compared to mock infection.

n = 3 independent biological replicates. Data were presented as mean ± SD. p values were calculated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. See also Figure S4 and Table S1.

Transcript profiles were then compared between mock and SARS-CoV-2-infected human primary hepatocyte and cholangiocyte organoids. Alignment with the viral genome confirmed robust viral replication in both hepatocyte organoids (Figure 4G) and cholangiocyte organoids (Figure 4H). PCA showed significant distinction between mock infected and SARS-CoV-2-infected hepatocyte organoids (Figure 4I). Volcano plots and heatmaps of differentially expressed genes in SARS-CoV-2-infected hepatocyte organoids revealed robust induction of chemokines, including CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, and CCL20, and significant downregulation of key hepatocyte metabolic markers, such as CYP7A1, CYP2A6, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6 (Figures 4J and S4F). KEGG gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) comparing mock-infected with SARS-CoV-2-infected hepatocyte organoids revealed over-represented and upregulated pathways, including cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, IL-17 signaling, chemokine signaling pathway, TNF signaling, and NF-κB signaling pathway, while cellular metabolism was largely downregulated (Figure 4K, Table S1).

PCA also suggested that mock and SARS-CoV-2-infected cholangiocyte organoid transcript profiles clustered separately (Figures 4L and S4G). Volcano plots and heatmap analysis of differentially expressed genes in SARS-CoV-2-infected cholangiocyte organoids revealed robust induction of chemokines, including CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, and CCL2 (Figures 4M and S4H). Consistent with results using hepatocyte organoids, KEGG GSEA comparing mock infected with SARS-CoV-2-infected cholangiocyte organoids revealed the upregulation of inflammatory pathways, including cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and IL-17 signaling (Figure 4N, Table S1), which is consistent with previous findings in COVID-19 lung autopsy samples (Han et al., 2020).

Finally, qRT-PCR analysis of SARS-CoV-2-infected (MOI = 0.1) hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, dopaminergic neurons, macrophages, microglia, and cortical neurons demonstrated high levels of viral sgRNA in cardiomyocytes (Figure S4I) and dopaminergic neurons (Figure S4J) and low or no level of viral sgRNA was detected in cortical neurons (Figure S4K), microglia (Figure S4L), and macrophages (Figure S4M), consistent with data from pseudo-entry virus infections.

Discussion

Although respiratory failure is the most common adverse outcome for COVID-19 patients, they often present with additional clinical complications involving the metabolic, cardiac, neurological, and gastrointestinal systems. Defining the tropism of SARS-CoV-2 is a first step toward understanding the pathology of SARS-CoV-2, which is critical for the development of anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapies. The most broadly used models for SARS-CoV-2 studies have been African green monkey-derived Vero cells or human cancer cell lines, which have clear limitations for modeling complex human organ systems. Therefore, the development of physiologically relevant human models to study SARS-CoV-2 infection is critically important. By developing a broad platform using system-wide human cell lineages and organoids, we discovered that pancreatic alpha and beta cells, liver organoids, cardiomyocytes, and dopaminergic neurons are permissive to SARS-CoV-2 virus infection using both pseudo-entry virus and live SARS-CoV-2 systems. One possible concern to using hPSC-derived cells for disease modeling is whether hPSC-derived cells can recapitulate the biology of SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults, since vertical infection of the fetus is not entirely clear (Lamouroux et al., 2020). Here, we used primary adult human islets to confirm the ACE2 expression profiles and the permissiveness of pancreatic alpha and beta cells to SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus and SARS-CoV-2 virus infection. In addition, adult liver organoids were used to confirm the permissiveness of hepatocytes and cholangiocytes to SARS-CoV-2 virus infection. The liver is susceptible to a variety of viral pathogens including hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E as well as atypical viruses such as herpes simplex virus family members along with cytomegalovirus (Talwani et al., 2011). Although human coronaviruses previously had not been considered to infect liver cells, our results are consistent with current COVID-19 clinical observations that more than 50% of patients have evidence of viral hepatitis (Ong et al., 2020). Consistent with these results, SARS-CoV-2 virus was recently shown to infect liver ductal organoids which caused increased cell death (Zhao et al., 2020).

It is particularly interesting that human pancreatic beta cells are infected by SARS-CoV-2. Previous studies suggested that ACE2 is expressed in the human pancreas (Yang et al., 2010). Using scRNA-seq and immunostaining, we showed that ACE2 is expressed in human adult alpha and beta cells. A number of studies support the hypothesis that viral infections play a causative role in Type 1 diabetes (Vehik et al., 2019), including enteroviruses (Krogvold et al., 2015) such as Coxsackievirus B (Anagandula et al., 2014; Hyöty et al., 1995), as well as rotavirus (Honeyman et al., 2000), mumps virus (Hyöty et al., 1988), and cytomegalovirus (Forrest et al., 1971). Enterovirus isolates obtained from newly diagnosed type 1 diabetic patients could infect and induce destruction of human islet cells in vitro (Elshebani et al., 2007). Here, we found that both hPSC-derived and adult human pancreatic beta cells are permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection. A recent clinical study showed a strong correlation between COVID-19 and type 2 diabetes (Zhu et al., 2020). Closer monitoring of individuals with high risk for diabetes is needed to evaluate the contribution of SARS-CoV-2 in previously infected COVID-19 patients to progression toward type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

In summary, we generated a library of hPSC-derived cells/organoids, including pancreatic endocrine cells, liver organoids, endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes, macrophages, microglia, cortical neurons, and dopaminergic neurons, to evaluate the permissiveness of normal human cells to SARS-CoV-2 infection. The hPSC-derived hepatic and pancreatic cells were found to be permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection, which was further validated using adult primary human islets, adult hepatic and cholangiocyte organoids, and a humanized mouse model. Transcript profiling after SARS-CoV-2 infection of hPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells and liver organoids revealed upregulation of chemokine expression, consistent with profiles of tissues obtained after autopsy of COVID-19 patients. Interestingly, several cell types expressing ACE2, such as endothelium, macrophages, and cortical neurons show low or no permissiveness to both SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus and SARS-CoV-2 virus, suggesting that factors besides ACE2 are also involved in viral entry (exemplified by the TMPRSS2 effector protein). The non-linear relationship between ACE2 and permissiveness to SARS-CoV-2 infection highlights the importance of using hPSC-derived primary-like cells instead of ACE2-overexpressing cells to study SARS-CoV-2 biology. Finally, this disease-relevant human cell/organoid-based platform can now be directly applied for drug screening and the evaluation of prospective anti-viral therapeutics.

Limitations of Study

While our study demonstrated permissiveness of multiple cell types to SARS-CoV-2 virus, whether or not some of these cells are major targets of viral infection in COVID-19 will not be clear without more thorough analysis of primary patient-derived samples. We focused here on viral entry and to some extent replication, but there may be cell lineage differences for viral release and secondary infection that could next be explored. The cell and organoid-based platform described here is a first step toward modeling COVID-19 in human organ systems but is clearly simplified compared to fully functioning and interacting adult human organs. In the future, the platform can be expanded to generate more complex organoid models, including incorporation of immune system components that are currently missing from the analysis.

STAR★Methods

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Polyclonal Guinea Pig Anti-Insulin | Dako | #A0564; RRID:AB_10013624 |

| Glucagon Rabbit Ab | Cell Signaling | #2760; RRID:AB_659831 |

| Polyclonal Rabbit Anti-Somatostatin | Dako | Cat#A0566; RRID:AB_2688022 |

| Human CD31/PECAM-1 Antibody | R&D Systems | Cat#AF806; RRID:AB_355617 |

| APC anti-mouse/human CD11b Antibody | Biolegend | Cat#101212; RRID:AB_312795 |

| APC anti-human CD206 (MMR) Antibody | Biolegend | Cat#321109; RRID:AB_571884 |

| Anti-ACE2 antibody | Abcam | Cat#ab15348-50UG; RRID:AB_301861 |

| Human ACE-2 Antibody | R & D Systems | Cat#AF933; RRID:AB_355722 |

| Firefly luciferase Monoclonal Antibody (CS 17) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#35-6700; RRID:AB_2533218 |

| Sarcomeric α-Actinin | Abcam | Cat#ab137346 |

| Recombinant Anti-Firefly Luciferase antibody | Abcam | Cat#ab185924 |

| Anti IBA-1 (rabbit) | Wako | Cat#019-19741; RRID:AB_839504 |

| Anti SPI1 (PU.1) (mouse) | Biolegend | Cat#658002; RRID:AB_2562720 |

| Chicken polyclonal anti-MAP2 | Abcam | Cat#ab5392; RRID:AB_2138153 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-FOXA2 | R&D Systems | Cat#AF2400; RRID:AB_2294104 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-γ Tubulin | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#T6557; RRID:AB_477584 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-21202; RRID:AB_141607 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Guinea Pig IgG (H+L) | Jackson Immunoresearch Labs | Cat#706-545-148; RRID:AB_2340472 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 594 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-21203; RRID:AB_2535789 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-21207; RRID:AB_141637 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-31573; RRID:AB_2536183 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-31571; RRID:AB_162542 |

| Donkey anti-Goat IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-21447; RRID:AB_2535864 |

| Donkey anti-Chicken IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Jackson Immunoresearch Labs | Cat#703-545-155; RRID:AB_2340375 |

| Donkey anti-Sheep IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-21448; RRID:AB_10374882 |

| DAPI | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-3598 |

| Chemicals | ||

| Y-27632 | MedchemExpress | #HY-10583 |

| CHIR99021 | Cayman Chemical | #13122 |

| SANT-1 | Sigma Aldrich | #S4572-25MG |

| Retinoic acid | Sigma Aldrich | #R2625-500MG |

| LDN 193189 hydrochloride - DM 3189 hydrochloride | Axon Medchem | #Axon 1509 |

| TPPB | Tocris Bioscience | #5343 |

| T3 hormone | Sigma Aldrich | #T6397-100MG |

| Zinc sulfate heptahydrate | Sigma Aldrich | #Z0251-100G |

| Heparin sodium salt from porcine intestinal mucosa | Sigma Aldrich | #H3149-1MU |

| γ-Secretase Inhibitor XX | Millipore | #565789-1MG |

| ALK5 Inhibitor II | Cayman Chemical | #14794 |

| L-Ascorbic acid | Sigma Aldrich | #A4544-100G |

| R428 | MedchemExpress | #HY-15150 |

| N-acetyl-L-cysteine | Sigma Aldrich | #A9165-5G |

| Trolox | Millipore | #648471 |

| XAV939 | Cayman | # 13596 |

| IWP | Tocris | #3533 |

| dibutyryl cAMP (cAMP) | Sigma Aldrich | #4043 |

| Poly(vinyl alcohol) | Sigma Aldrich | #P8136 |

| L-Ascorbic acid 2-phosphate sesquimagnesium salt hydrate | Sigma Aldrich | #A8960 |

| SB431542 | R&D Systems | #1614/50 |

| Dorsomorphin dihydrochloride | R&D Systems | #3093/50 |

| IWP2 | R&D Systems | #3533/50 |

| Dexamethasone | Sigma-Aldrich | #D4902 |

| 8-Bromo-cAMP | Sigma-Aldrich | #B5386 |

| IBMX | Sigma-Aldrich | #I5879 |

| DAPT | R&D Systems | #2634 |

| 1-Thioglycerol | Sigma Aldrich | #M6145 |

| Growth factors | ||

| Activin A | R&D Systems | #338-AC-500/CF |

| Recombinant Human KGF (FGF-7) Protein | Peprotech | #100-19-500UG |

| Recombinant Human bFGF Protein | Peprotech | #100-18B-500UG |

| Recombinant Human BMP-4 Protein | R & D Systems | #314-BP |

| Recombinant Human VEGF Protein | R&D Systems | #293-VE-500/CF |

| Recombinant Human SCF Protein | R&D Systems | #7466-SC-100/CF |

| Recombinant Human IL-6 Protein | R&D Systems | #206-IL-200/CF |

| Recombinant Human IL-3 Protein | R&D Systems | #203-IL-050/CF |

| Recombinant Human TPO Protein | R&D Systems | #288-TP-200/CF |

| Recombinant Human M-CSF Protein | R&D Systems | #216-MC-025 |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BNDF) | R&D Systems | #248-BD |

| Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) | Peptrotech | #450-10 |

| Transforming growth factor type β3 (TGFβ3) | R&D Systems | #243-B3 |

| DAPT | R&D Systems | #2634 |

| Vitronectin (VTN-N) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | #A14700 |

| SHH C25II | R&D Systems | #464-SH |

| Recombinant Human FGF-10 Protein | R&D Systems | #345-FG-250 |

| Recombinant Human KGF/FGF-7 Protein | R&D Systems | #251-KG-01M |

| Recombinant Human bFGF | R&D Systems | #233-FB-500 |

| Recombinant Human HGF Protein | R&D Systems | #294-HG |

| Recombinant Human OSM Protein | R&D Systems | #295-OM |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Human: H9 (WA-09) hESC line | WiCell Research Institute | NIHhESC-10-0062 |

| hESC line H9 | Harvard University | 0022 |

| hESC line MEL-1 | University of Queensland | 0139 |

| hESC line H1 | Harvard University | 0014 |

| hESC line-RUES2 | The Rockefeller University | 0013 |

| 293T | ATCC | #CRL-11268 |

| Vero E6 | ATCC | #CRL-1586 |

| Culture Medium | ||

| StemFlex | GIBCO Thermo Fisher | #A3349401 |

| MCDB 131 Medium, no glutamine | Thermo Fisher Scientific | #10372019 |

| STEMdiff™ APEL™2 Medium | Stem Cell Technologies | #05270 |

| Endothelial Cell Growth Medium MV2 (Ready-to-use) | PromoCell | #C-22022 |

| mTeSR1 Complete Kit | Stem Cell Technologies | #85850 |

| F12 | GIBCO Thermo Fisher | #31765035 |

| Lipids | GIBCO Thermo Fisher | #11905031 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin (5,000 U/mL) | GIBCO Thermo Fisher | #15070063 |

| MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution (100X) | GIBCO Thermo Fisher | #11140050 |

| IMDM | GIBCO Thermo Fisher | #21056023 |

| GlutaMAX Supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | #35050079 |

| ITS-X | Thermo Fisher Scientific | #51500056 |

| Accutase | StemCell Technologies, Inc. | # 07920 |

| ReleSR | StemCell Technologies, Inc. | # 05872 |

| B27 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | # A3582801 |

| B27 minus insulin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | # A1895601 |

| Matrigel | Corning | #354234 |

| Essential 8 (E8) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | #A1517001 |

| Neurobasal | Life Technologies | #21103-049 |

| N2 supplement-B | Stem Cell Technologies | #7156 |

| B27 | Life Technologies | #12587-010 |

| Poly-L-Ornithine (PO) | Sigma Aldrich | #P3655 |

| Mouse Laminin I (LAM) | R&D Systems | #3400-010-1 |

| DMEM/F12 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | # 10565018 |

| Monothioglycerol | Sigma Aldrich | #M6145 |

| Fibronectin (FN) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | #356008 |

| Experimental Models: Mouse models | ||

| SCID-beige mice | The Jackson Laboratory | N/A |

| Deposited Data | ||

| scRNA-seq | this paper | GEO: GSE147903 |

| RNA-seq | this paper | GEO: GSE151803 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Cell Ranger | 10X Genomics | https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/overview/welcome |

| Scran | Lun et al., 2016 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/scran.html |

| Rstudio | Rstudio | https://rstudio.com |

| Seurat R package v3.1.4 | Butler et al., 2018 | https://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

| DAVID6.8 | LHRI | https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp |

| Adobe illustrator CC2017 | Adobe | https://www.adobe.com/products/illustrator.html |

| Graphpad Prism 6 | Graphpad software | https://www.graphpad.com |

| ToppCell Atlas | Toppgene | https://toppgene.cchmc.org/ |

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Shuibing Chen (shc2034@med.cornell.edu).

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

scRNA-seq data is available from the GEO repository database: GSE147903. RNA-seq data is available from the GEO repository database: GSE151803.

Method Details

hPSC maintenance and pancreatic differentiation

Pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation was performed using INS GFP/W MEL-1 cells. Cells were cultured on Matrigel-coated 6-well plates in StemFlex medium (GIBCO Thermo Fisher). Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. hESCs were differentiated using a previously reported strategy (Zeng et al., 2016). In brief, on day 0, cells were exposed to basal medium RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1 × Glutamax (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 50 μg/mL Normocin, 100 ng/mL Activin A (R&D systems), and 2 μM of CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor 3, Cayman Chemical) for 24 h. The medium was changed on day 1 to basal RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1 × Glutamax (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 50 μg/mL Normocin, 0.2% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Corning), 100 ng/mL Activin A (R&D systems) for 2 days. On day 3, the resulting definitive endoderm cells were cultured in MCDB 131 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 1 × Glutamax, 10 mM glucose (Sigma Aldrich) at final concentration, 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Lampire), 0.25 mM L-ascorbic acid (Sigma Aldrich) and 50 ng/mL of fibroblast growth factor 7 (FGF-7, Peprotech) for 2 days to acquire primitive gut tube. On day 5, the cells were induced to differentiate to posterior foregut in MCDB 131 medium supplemented with 2.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 1 × Glutamax, 10 mM glucose at final concentration, 2% BSA, 0.25 mM L-ascorbic acid, 50 ng/mL of FGF-7, 1 μM Retinoic acid (RA; Sigma Aldrich), 100 nM LDN193189 (LDN, Axon Medchem), 1:200 ITS-X (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 200 nM TPPB (Tocris Bioscience) and 0.25 μM SANT-1 (Sigma Aldrich) for 2 days. On day 7, the cells were induced to differentiate to pancreatic endoderm in MCDB 131 medium supplemented with 2.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 1 × Glutamax, 10 mM glucose at final concentration, 2% BSA, 0.25 mM L-ascorbic acid, 2 ng/mL of FGF-7, 0.1 μM RA, 200 nM LDN193189, 1:200 ITS-X, 100 nM TPPB and 0.25 μM SANT-1 for 3 days. On day 10, the cells were induced to differentiate to pancreatic endocrine precursors in MCDB 131 medium supplemented with 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 1 × Glutamax, 20 mM glucose at final concentration, 2% BSA, 0.05 μM RA, 100 nM LDN, 1:200 ITS-X, 0.25 μM SANT-1, 1 mM T3 hormone (Sigma Aldrich), 10 μM ALK5 inhibitor II (Cayman Chemical), 10 μM zinc sulfate heptahydrate (Sigma Aldrich) and 10 μg/mL of heparin (Sigma Aldrich) for 3 days. On day 13, cells were exposed to MCDB 131 medium supplemented with 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 1 × Glutamax, 20 mM glucose at final concentration, 2% BSA, 100 nM LDN193189, 1:200 ITS-X, 1 μM T3, 10 μM ALK5 inhibitor II, 10 μM zinc sulfate, 10 μg/mL of heparin, 100 nM gamma secretase inhibitor XX (Millipore) for the first 7 days. On day 27, cells were exposed to MCDB 131 medium supplemented with 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 1 × Glutamax, 20 mM glucose at final concentration, 2% BSA, 1:200 ITS-X, 1 μM T3, 10 μM ALK5 inhibitor II, 10 μM zinc sulfate heptahydrate, 10 μg/mL of heparin, 1 mM N-acetyl cysteine (Sigma Aldrich), 10 μM Trolox (Millipore), 2 μM R428 (MedchemExpress) for 7-15 days. The medium was subsequently refreshed every day. The protocol details are summarized in Figure S1A.

hPSC liver differentiation

In brief, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were cultured in monolayers on Matrigel. Differentiation was achieved by sequential exposure to 100 ng/mL Activin A, 20 ng/mL BMP-4, 10 ng/mL bFGF and 20 ng/mL hepatocyte growth factor (HGF, R&D Systems) (Si-Tayeb et al., 2010). Cells at the hepatoblast stage were subsequently aggregated into spheroids and then exposed to continued 20 ng/mL HGF and 20 ng/mL oncostatin M (R&D Systems). The protocol details are summarized in Figure S1B.

hPSC endothelial differentiation

To derive endothelial cells from hPSCs, we optimized a previously reported strategy (Harding et al., 2017). Briefly, hESC line H1 were passaged onto Matrigel-coated 6-well plates in StemFlex medium with an additional 10 ng/mL of bFGF. After 1 day, culture medium was changed to StemDiff APEL medium (STEMCELL Technologies) with an additional of 6 μm CHIR99021 for 2 days. Then, cells were cultured in StemDiff APEL medium with an additional of 25 ng/mL BMP-4, 10 ng/mL bFGF and 50 ng/mL VEGF (R&D Systems) for another two days. On day 4, cells were dissociated with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies) and reseeded onto p100 culture dishes in EC Growth Medium MV2 (Promocell) with an additional 50 ng/mL VEGF for 4-6 days. Finally, endothelial cells were generated and passaged every 3-5 days in EC Growth Medium MV2 with an additional 50 ng/mL VEGF. The protocol details are summarized in Figure S1C.

hPSC cardiomyocyte differentiation

For monolayer-based cardiomyocyte (CM) differentiation, hPSCs were passaged at density of 3x105 cells/well of 6-well plate and grown for 48 h to 90% confluence in the humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. On day 0, the medium was replaced with RPMI 1640 supplemented with B27 without insulin and 6 μM CHIR99021. On day 2, the medium was changed to RPMI 1640 supplemented with B27 without insulin for 24 h. Day 3, medium was refreshed to RPMI 1640 supplemented with B27 without insulin and 5 μM XAV939 for another 48 h. On day 5, the medium was changed back to RPMI-B27 without insulin for 48 h, and then switched to RPMI 1640 plus normal B27 for another 48 h. On day 9, the medium was transiently changed to RPMI 1640-B27 without D-glucose for two days to allow metabolic purification of CMs. From that day on, fresh RPMI 1640-B27 was changed every two days. On day 30, cells were dissociated with Accutase at 37°C followed by resuspending with fresh RPMI 1640-B27 plus Y-27632 and reseeding into 96-well plates. After 24 h, medium was switched to RMPI 1640-B27 without Y-27632 for following virus infection tests. The protocol details are summarized in Figure S1D.

hPSC macrophage differentiation

We derived macrophages from hESC line H9 and adapted a previously reported protocol (Cao et al., 2019). First, H9 cells were lifted with ReLeSR (STEMCELL Technologies) as small clusters onto Matrigel-coated 6-well plates at low density. On day 0, IF9S medium was supplemented with 50 ng/mL BMP-4, 15 ng/mL Activin A and 1.5 μm CHIR99021. On day 2, medium was refreshed with IF9S medium with 50 ng/mL VEGF, 50 ng/mL bFGF, 50 ng/mL SCF (R&D Systems) and 10 μm SB431542 (Cayman Chemical). On day 5 and day 7, medium was changed into IF9S with 50 ng/mL IL-6 (R&D Systems), 12 ng/mL IL-3 (R&D Systems), 50 ng/mL VEGF, 50 ng/mL bFGF, 50 ng/mL SCF and 50 ng/mL TPO (R&D Systems). On day 9, cells were dissociated with TrypLE (Life Technologies) and resuspended in IF9S medium with 50 ng/mL IL-6, 12 ng/mL IL-3 and 80 ng/mL M-CSF (R&D Systems) onto low attachment plates. On day 13 and day 15, medium was changed and supplemented with 50 ng/mL IL-6, 12 ng/mL IL-3 and 80 ng/mL M-CSF to generate monocytes. After day 15, monocytes were seeded onto normal plates and cultured in IF9S medium supplemented with 80ng/mL M-CSF for 4 days. All differentiation steps were cultured under normoxic conditions at 37°C, 5% CO2. The protocol details are summarized in Figure S1E.

hPSC microglia differentiation

hESC line H9 was used for microglial differentiation. For microglial differentiation, hESCs were harvested using Accutase and plated on Matrigel-coated dishes at low density in E8 medium supplemented with Y-27632, Activin A, BMP-4 and CHIR99021, followed by WNT-inhibition. On day 2, bFGF was added to the medium. On day 3, cells were dissociated and passaged at low density on Matrigel-coated dishes in E6 medium supplemented with VEGF, bFGF and Y-27632. On day 4, Y-27632 was removed from medium. For the four following days, a cocktail was used of E6 containing the following cytokines/growth factors: VEGF, bFGF, SCF, IL-6, TPO, IL-3. Then, round cells were harvested from the culture between day 10-14 and replated on tissue culture treated plastic dishes in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS, M-CSF, IL-34. Maturation was achieved over 4-8 weeks of culture. The protocol details are summarized in Figure S1F.

hPSC cortical and dopamine neuron differentiation

Cortical and mDA differentiation were performed using H9 hESCs. hESCs were grown on VTN-N (Thermo Fisher Scientific)-coated 6-well plates in E8-essential medium. Cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2. hESCs were differentiated with an optimized protocol from a previously reported study (Zhou et al., 2018).

Adult liver organoid culture

Human hepatocytes and human nonparenchymal fractions were obtained from the Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) funded by (R01-DK-7-0004/HHSN26700700004C). Human liver tissue was digested to obtain cellular fractions. 2,500 cells were mixed 1:1 with Matrigel and placed at the bottom of a 6-well plate. 5 drops per well were added and then incubated for 5 min at 37°C. Medium was used that contained DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1:50 B27 supplement (without vitamin A), 1:100 N2 supplement, 1 mM N-acetylcysteine, 10% (vol/vol) Rspo1-conditioned medium, 10 mM nicotinamide, 10 nM recombinant human [Leu15]-gastrin I, 50 ng/mL recombinant human EGF, 100 ng/mL recombinant human FGF-10, 25 ng/mL recombinant human HGF, 10 μM Forskolin and 5 μM A83-01. Medium was changed every 3-4 days and cultures split at about 14 days after initial plating with following split every 5-7 days.

Human islets

The pancreatic organs were obtained from the local organ procurement organization under the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). The islets were isolated in the Human Islet Core at University of Pennsylvania following the guidelines of Clinical Islet Transplantation consortium protocol (Ricordi et al., 2016). Briefly, the pancreas was digested following intraductal injection of Collagenase & Neutral Protease in Hanks’ balanced salt solution. Liberated islets were then purified on continuous density gradients (Cellgro/Mediatech) using the COBE 2991 centrifuge and cultured in CIT culture media and kept in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Cell Lines

HEK293T (human [Homo sapiens] fetal kidney) and Vero E6 (African green monkey [Chlorocebus aethiops] kidney) were obtained from ATCC (https://www.atcc.org/). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 I.U./mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. All cell lines were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2.

SARS-CoV-2-Pseudo-Entry Viruses

Recombinant Indiana VSV (rVSV) expressing SARS-CoV-2 spikes was generated as previously described (Nie et al., 2020; Whitt, 2010; Zhao et al., 2017). HEK293T cells were grown to 80% confluency before transfection with pCMV3-SARS-CoV2-spike (kindly provided by Dr. Peihui Wang, Shandong University, China) using FuGENE 6 (Promega). Cells were cultured overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. The next day, the medium was removed and VSV-G pseudotyped ΔG-luciferase (G∗ΔG-luciferase, Kerafast) was used to infect the cells in DMEM at an MOI of 3 for 1 h before washing the cells with 1X DPBS three times. DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS and 100 I.U. /mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin was added to the infected cells and they were cultured overnight as described above. The next day, the supernatant was harvested and clarified by centrifugation at 300xg for 10 min before aliquoting and storing at −80°C.

SARS-CoV-2 entry virus infections

To assay pseudo-typed virus infection, cells were seeded in 96 well plates. Pseudo-typed virus was added at the indicated MOI. At 2chpi, the infection medium was replaced with fresh medium. At 24chpi, cells were harvested for luciferase assays or immunohistochemistry analyses. For liver organoids, organoids were seeded in 24-well plates, pseudo-typed virus was added and centrifuged the plate at 1200 g, 1 h. At 24chpi, organoids were fixed for immunohistochemistry or harvested for luciferase assay following the Luciferase Assay System protocol (E1501, Promega).

SARS-CoV-2 Virus infections

SARS-CoV-2, isolate USA-WA1/2020 (NR-52281) was deposited by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention and obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH. SARS-CoV-2 was propagated in Vero E6 cells in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS, 4.5 g/L D-glucose, 4 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM Non-Essential Amino Acids, 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate and 10 mM HEPES as described previously (Blanco-Melo et al., 2020).

SARS-CoV-2 infections of hPSC-derived cells/organoids were performed in the respective cell/organoid growth media at the indicated MOIs for 24 h at 37°C. At 24 hpi, cells were washed three times with PBS. For RNA analysis cells were lysed in TRIzol (Invitrogen). For immunofluorescence staining cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 24 h at room temperature.

All work involving live SARS-CoV-2 was performed in the CDC/USDA-approved BSL-3 facility of the Global Health and Emerging Pathogens Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in accordance with institutional biosafety requirements.

Xenograft formation

hESCs-dervied endocrine cells were resuspended in 40 μL Matrigel and transplanted under the kidney capsule of 6 to 8 week old male SCID-beige mice. Two months post-transplantation, SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus was inoculated locally at 1x104 PFU. At 24 hpi, the mice were euthanized and used for immunohistochemistry analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Histology on tissues from mice was performed on frozen sections from xenografts. Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and transferred to 30% sucrose, followed by snap freezing in O.C.T (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Living cells in culture were directly fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 25 min, followed with 15 min permeabilization in 0.1% Triton X-100. For immunofluorescence, cells or tissue sections were immuno-stained with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight and secondary antibodies at RT for 1 h. The information for primary antibodies and secondary antibodies is provided in Table S2. Nuclei were counterstained by DAPI.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA samples were prepared from cells/organoids and DNase I treated using TRIzol and Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Plus kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To quantify viral replication, measured by the expression of sgRNA transcription of the viral N gene, one-step quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SuperScript III Platinum SYBR Green One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen) with primers specific for the TRS-L and TRS-B sites for the N gene as well as ACTB as an internal reference. Quantitative real-time PCR reactions were performed on a LightCycler 480 Instrument II (Roche). Delta-delta-cycle threshold (ΔΔCT) was determined relative to ACTB levels and normalized to mock infected samples. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean from three biological replicates. The sequences of primers/probes are provided in Table S3.

Human islet sample sequencing and gene expression UMI counts matrix generation

The 10X libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq500 sequencer. The sequencing data were primarily analyzed by the 10X cellranger pipeline (v3.0.2) in two steps. In the first step, cellranger mkfastq demultiplexed samples and generated fastq files; and in the second step, cellranger count aligned fastq files to the 10X pre-built human reference genome (GRCh38 v3.0.0) and extracted gene expression UMI counts matrix.

Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis

We filtered cells with less than 300 or more than 6000 genes detected as well as cells with mitochondria gene content greater than 15%, and used the remaining cells (3990, 5594 and 6563 cells for the three samples) for downstream analysis. We normalized the gene expression UMI counts using a deconvolution strategy implemented by the R scran package (v.1.14.1). In particular, we pre-clustered cells using the quickCluster function; we computed size factor per cell within each cluster and rescaled the size factors by normalization between clusters using the computeSumFactors function; we normalized the UMI counts per cell by the size factors and took a logarithm transform using the normalize function. We further normalized the UMI counts across samples using the multiBatchNorm function in the R batchelor package (v1.2.1). We identified highly variable genes using the FindVariableFeatures function in the R Seurat (v3.1.0) (Stuart et al., 2019), and selected the top 3000 variable genes after excluding mitochondria genes, ribosomal genes and dissociation-related genes. The list of dissociation-related genes was originally built on mouse data (van den Brink et al., 2017); we converted them to human ortholog genes using Ensembl BioMart. We aligned the three samples based on their mutual nearest neighbors (MNNs) using the fastMNN function in the R batchelor package, this was done by performing a principal component analysis (PCA) on the highly variable genes and then correcting the principal components (PCs) according to their MNNs. We selected the corrected top 50 PCs for downstream visualization and clustering analysis. We ran UMAP dimensional reduction using the RunUMAP function in the R Seurat package with the number of neighboring points setting to 35 and training epochs setting to 1000. We clustered cells into thirteen clusters by constructing a shared nearest neighbor graph and then grouping cells of similar transcriptome profiles using the FindNeighbors function and FindClusters function (resolution set to 0.1) in the R Seurat package. We identified marker genes for each cluster by performing differential expression analysis between cells inside and outside that cluster using the FindMarkers function in the R Seurat package. After reviewing the clusters, we merged them into nine clusters representing nine cell types (acinar cells, ductal cells, beta cells, alpha cells, mesenchymal cells, delta cells, pp cells, endothelial cells and immune cells) for further analysis. We re-identified marker genes for the merged nine clusters and selected top 10 positive marker genes per cluster for heatmap plot using the DoHeatmap function in the R Seurat package. The rest plots were generated using the R ggplot2 package.

Human studies

For RNA analysis, tissue was acquired from four deceased COVID19 human subjects during autopsy and processed in TRIZOL. Tissue samples were provided from Weill Cornell Department of Pathology. The uninfected human lung samples were similarly obtained. The Tissue Procurement Facility operates under Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocol and follows guidelines set by HIPAA. Experiments using samples from human subjects were conducted in accordance with local regulations and with the approval of the institutional review board at the Weill Cornell Medicine under protocol 20-04021814.

RNA-Seq before and following viral infections

Organoid infections were performed at the described MOI in DMEM supplemented with 0.3% BSA, 4.5 g/L D-glucose, 4 mM L-glutamine and 1 μg/mL TPCKtrypsin and harvested 24 hpi. Total RNA was extracted in TRIzol (Invitrogen) and DNase I treated using Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Plus kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNaseq libraries of polyadenylated RNA were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform. The resulting single end reads were checked for quality (FastQC v0.11.5) and processed using the Digital Expression Explorer 2 (DEE2) (Ziemann et al., 2019) workflow. Adaptor trimming was performed with Skewer (v0.2.2) (Jiang et al., 2014). Further quality control done with Minion, part of the Kraken package (Davis et al., 2013). The resultant filtered reads were mapped to human reference genome GRCh38 using STAR aligner (Dobin et al., 2013) and gene-wise expression counts generated using the “-quantMode GeneCounts” parameter. BigWig files were generated using the bamCoverage function in deepTools2 (v.3.3.0) (Ramírez et al., 2016).

After further filtering and quality control, R package edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010) was used to calculate RPKM and Log2 counts per million (CPM) matrices as well as to perform differential expression analysis. Principal component analysis was performed using Log2 CPM values and gene set analysis was run with WebGestalt (Liao et al., 2019). Heatmaps and bar plots were generated using Graphpad Prism software, version 7.0d.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

N = 3 independent biological replicates were used for all experiments unless otherwise indicated. n.s. indicates a non-significant difference. P-values were calculated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test unless otherwise indicated. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (DP3DK111907, R01DK116075, R01DK119667, and R01 DK124463 to S.C.), Department of Surgery, Weill Cornell Medicine (T.E., F.C.P., S.C.), NCI (R01CA234614), NIAID (2R01AI107301), NIDDK (R01DK121072 and 1RO3DK117252), Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine (R.E.S.), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA-16-35-INTERCEPT-FP-006 to B.R.T.), the Jack Ma Foundation (D.D.H.), NIH (1R01AG056298 and P30CA008748 to L.S.), NYSTEM (DOH01-STEM5-2016-00300-C32599GG to L.S and S.C.), and U.S. National Institutes of Health (1K99 CA226353 -01A1, H.J.C). S.C. and R.E.S. are supported as Irma Hirschl Trust Research Award Scholars. Human islets were received from the University of Pennsylvania human islet center with funding provided by the NIDDK-supported Human Pancreas Analysis Program (HPAP) (https://hpap.pmacs.upenn.edu/citation) grant UC4 DK112217 to A.N. V.G. is a Weill Cornell Department of Medicine Fund for the Future awardee, supported by the Kendrick Foundation. S.R.G. was supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein Individual Predoctoral NRSA for MD/PhD Fellowship (1F30MH115616). G.C. was supported by a EMBO postdoctoral fellowship and a NYSTEM postdoctoral fellowship. The authors would like to thank Dr. Tom Moran, Center for Therapeutic Antibody Discovery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for providing the anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody.

Author Contributions

S.C., R.E.S., T.E., B.R.T., D.D.H., H.W., H.J.C., D.L., A.B., and L.S. conceived and designed the experiments. L.Y., Y. Han, V.G., X.T., J.Z., Z.Z., F.J., X.D., F.C.P., Y.B., T.W.K., O.H., G.C., S.G., M.C., X.D., V.C., and D.T.N. performed organoid differentiation, in vivo transplantation, and pseudo-entry virus infection. P.W. and Y. Huang performed SARS2-CoV-2 pseudo-entry virus-related experiments. C.L. and A.N. performed the human islets experiments. B.E.N.-P., D.A.H., and B.R.T. performed SARS2-CoV-2-related experiments. D.R., S.H., T.Z., and J.X. performed the scRNA-sequencing and bioinformatics analysis.

Declaration of Interests

R.E.S. is on the scientific advisory board of Miromatrix Inc. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Published: June 19, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2020.06.015.

Supplemental Information

List of Differentially Expressed Genes in SARS-CoV-2 vs. Mock Infected hPSC-Derived Pancreatic Endocrine Cells, Adult Hepatocyte Organoids, and Adult Cholangiocyte Organoids

References

- Anagandula M., Richardson S.J., Oberste M.S., Sioofy-Khojine A.B., Hyöty H., Morgan N.G., Korsgren O., Frisk G. Infection of human islets of Langerhans with two strains of Coxsackie B virus serotype 1: assessment of virus replication, degree of cell death and induction of genes involved in the innate immunity pathway. J. Med. Virol. 2014;86:1402–1411. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Melo D., Nilsson-Payant B.E., Liu W.C., Uhl S., Hoagland D., Møller R., Jordan T.X., Oishi K., Panis M., Sachs D. Imbalanced Host Response to SARS-CoV-2 Drives Development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181:1036–1045.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein S.R., Rubino F., Khunti K., Mingrone G., Hopkins D., Birkenfeld A.L., Boehm B., Amiel S., Holt R.I., Skyler J.S. Practical recommendations for the management of diabetes in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:546–550. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30152-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A., Hoffman P., Smibert P., Papalexi E., Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:411–420. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Yakala G.K., van den Hil F.E., Cochrane A., Mummery C.L., Orlova V.V. Differentiation and Functional Comparison of Monocytes and Macrophages from hiPSCs with Peripheral Blood Derivatives. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;12:1282–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Su B., Guo X., Sun W., Deng Y., Bao L., Zhu Q., Zhang X., Zheng Y., Geng C. Potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 identified by high-throughput single-cell sequencing of convalescent patients’ B cells. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.025. Published online May 18, 2020. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H., Chan J.F.-W., Yuen T.T.-T., Shuai H., Yuan S., Wang Y., Hu B., Yip C.C.-Y., Tsang J.O.-L., Huang X. Comparative tropism, replication kinetics, and cell damage profiling of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV with implications for clinical manifestations, transmissibility, and laboratory studies of COVID-19: an observational study. The Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:E14–E23. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.P., van Dongen S., Abreu-Goodger C., Bartonicek N., Enright A.J. Kraken: a set of tools for quality control and analysis of high-throughput sequence data. Methods. 2013;63:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elshebani A., Olsson A., Westman J., Tuvemo T., Korsgren O., Frisk G. Effects on isolated human pancreatic islet cells after infection with strains of enterovirus isolated at clinical presentation of type 1 diabetes. Virus Res. 2007;124:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest J.M., Menser M.A., Burgess J.A. High frequency of diabetes mellitus in young adults with congenital rubella. Lancet. 1971;2:332–334. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)90057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal P., Choi J.J., Pinheiro L.C., Schenck E.J., Chen R., Jabri A., Satlin M.J., Campion T.R., Jr., Nahid M., Ringel J.B. Clinical Characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Yang L., Duan X., Duan F., Nilsson-Payant B.E., Yaron T.M., Wang P., Tang X., Zhang T., Zhao Z. Identification of candidate COVID-19 therapeutics using hPSC-derived lung organoids. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.079095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harding A., Cortez-Toledo E., Magner N.L., Beegle J.R., Coleal-Bergum D.P., Hao D., Wang A., Nolta J.A., Zhou P. Highly Efficient Differentiation of Endothelial Cells from Pluripotent Stem Cells Requires the MAPK and the PI3K Pathways. Stem Cells. 2017;35:909–919. doi: 10.1002/stem.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms J., Kremer S., Merdji H., Clere-Jehl R., Schenck M., Kummerlen C., Collange O., Boulay C., Fafi-Kremer S., Ohana M. Neurologic Features in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2268–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.H., Nitsche A. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeyman M.C., Coulson B.S., Stone N.L., Gellert S.A., Goldwater P.N., Steele C.E., Couper J.J., Tait B.D., Colman P.G., Harrison L.C. Association between rotavirus infection and pancreatic islet autoimmunity in children at risk of developing type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2000;49:1319–1324. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.079095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyöty H., Leinikki P., Reunanen A., Ilonen J., Surcel H.M., Rilva A., Käär M.L., Huupponen T., Hakulinen A., Mäkelä A.L. Mumps infections in the etiology of type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetes Res. 1988;9:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyöty H., Hiltunen M., Knip M., Laakkonen M., Vähäsalo P., Karjalainen J., Koskela P., Roivainen M., Leinikki P., Hovi T. A prospective study of the role of coxsackie B and other enterovirus infections in the pathogenesis of IDDM. Childhood Diabetes in Finland (DiMe) Study Group. Diabetes. 1995;44:652–657. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.6.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Lei R., Ding S.W., Zhu S. Skewer: a fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogvold L., Edwin B., Buanes T., Frisk G., Skog O., Anagandula M., Korsgren O., Undlien D., Eike M.C., Richardson S.J. Detection of a low-grade enteroviral infection in the islets of langerhans of living patients newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64:1682–1687. doi: 10.2337/db14-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamouroux A., Attie-Bitach T., Martinovic J., Leruez-Ville M., Ville Y. Evidence for and against vertical transmission for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.039. Published online May 4, 2020. 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei C., Qian K., Li T., Zhang S., Fu W., Ding M., Hu S. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus by recombinant ACE2-Ig. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2070. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16048-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Wang J., Jaehnig E.J., Shi Z., Zhang B. WebGestalt 2019: gene set analysis toolkit with revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W199–W205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lun A.T.L., McCarthy D.J., Marioni J.C. A step-by-step workflow for low-level analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data with Bioconductor. F1000Res. 2016;5:2122. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.9501.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma-Lauer Y., Carbajo-Lozoya J., Hein M.Y., Müller M.A., Deng W., Lei J., Meyer B., Kusov Y., von Brunn B., Bairad D.R. p53 down-regulates SARS coronavirus replication and is targeted by the SARS-unique domain and PLpro via E3 ubiquitin ligase RCHY1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E5192–E5201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603435113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J., Li Q., Wu J., Zhao C., Hao H., Liu H., Zhang L., Nie L., Qin H., Wang M. Establishment and validation of a pseudovirus neutralization assay for SARS-CoV-2. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:680–686. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1743767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J., Young B.E., Ong S. COVID-19 in gastroenterology: a clinical perspective. Gut. 2020;69:1144–1145. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou X., Liu Y., Lei X., Li P., Mi D., Ren L., Guo L., Guo R., Chen T., Hu J. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1620. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15562-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L., Mu M., Yang P., Sun Y., Wang R., Yan J., Li P., Hu B., Wang J., Hu C. Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 Patients With Digestive Symptoms in Hubei, China: A Descriptive, Cross-Sectional, Multicenter Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020;115:766–773. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleasure S.J., Green A.J., Josephson S.A. The Spectrum of Neurologic Disease in the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Pandemic Infection: Neurologists Move to the Frontlines. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1065. Published online April 10, 2020. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez F., Ryan D.P., Grüning B., Bhardwaj V., Kilpert F., Richter A.S., Heyne S., Dündar F., Manke T. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W160-5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricordi C., Goldstein J.S., Balamurugan A.N., Szot G.L., Kin T., Liu C., Czarniecki C.W., Barbaro B., Bridges N.D., Cano J. National Institutes of Health-Sponsored Clinical Islet Transplantation Consortium Phase 3 Trial: Manufacture of a Complex Cellular Product at Eight Processing Facilities. Diabetes. 2016;65:3418–3428. doi: 10.2337/db16-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]