Abstract

This cohort study examines the potential association of the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors with testicular histopathologic conditions.

The emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has provided previously unachievable curative therapy for many patients, particularly those with metastatic melanoma.1 However, the long-term outcomes for patients using ICIs are only beginning to be investigated. One important potential unexplored adverse effect is impaired male fertility. The current American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines (July 2018) state that “sperm cryopreservation is effective, and health care providers should discuss sperm banking with postpubertal males receiving cancer treatment.”2(p1995) The direct association of ICI treatment with spermatogenesis has not been explored, to our knowledge.3 It will be critical to determine the risk to future male fertility for patients undergoing ICI therapy to accurately guide pretreatment counseling. To address the association between the potential gonadotoxic effect of ICIs and spermatogenesis, to our knowledge, we performed the first retrospective review of an index patient who became infertile after ICI therapy and subsequently died, and we performed a retrospective cohort cadaver study of patients with metastatic melanoma.

Methods

We queried the Johns Hopkins Pathology database (January 1, 1985, through December 31, 2016) for untreated patients and the Johns Hopkins Legacy Gift Rapid Autopsy database (January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2016) for patients with a history of metastatic melanoma treated using immunotherapy for more than 1 month (ipilimumab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab). Tissue specimens of the testes were retrospectively examined from deceased patients for whom autopsies were performed. Patients who had received systemic chemotherapy or radiotherapy to the thorax, abdomen, pelvis, or lower extremities were excluded. We obtained approval from the Johns Hopkins Hospital institutional review board for review of pathologic samples under a consent waiver.

A proportioned control cohort was matched for age at tissue acquisition. Control samples came from men with a history of metastatic melanoma who had never undergone immunotherapy, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy to the thorax, abdomen, pelvis, or lower extremities between January 1, 1986, and December 31, 2016. For each patient, data on demographic characteristics, time from death to autopsy, treatment history, type of immunotherapy, and duration of therapy were recorded.

Autopsy and biopsy tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin within 24 hours after death. The testicular pathology slides were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and observed under light microscopy by a blinded independent genitourinary pathologist (A.M.). Testicular histopathologic conditions were diagnosed for each individual, and the degree of spermatogenesis was quantified using the Johnsen scoring system.4 Owing to the restrictive sample size, we present descriptive data on testicular pathologic conditions. Statistical analysis was performed from February 21, 2018, to December 12, 2019. Comparisons between cohorts for age at diagnosis, age at death, and time to autopsy were performed using a Mann-Whitney test using Prism, version 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc).

Results

We queried more than 10 000 potential participants and identified a total of 13 men (median age, 54 years [range, 23-78 years]) with metastatic melanoma who had testicular autopsy tissue specimens available. Of these, 7 underwent immunotherapy and 6 were treatment naive. There was no difference between groups for age at diagnosis, age at death, and time to autopsy (Table). Six of the 7 men (86%) with metastatic melanoma who received ICI therapy had impaired spermatogenesis, including focal active spermatogenesis (n = 1), hypospermatogenesis (n = 2), and Sertoli-cell–only syndrome (n = 3). Two of the 6 men (33%) who were untreated had impaired spermatogenesis (Figure). We did not identify any increased peritubular hyalinization or fibrosis in the treated group, and there were no Leydig cell abnormalities noted in any patients.

Table. Characteristics and Testicular Morphologic Conditions of Patients With Metastatic Melanoma With or Without Immunotherapy Treatment.

| Age at diagnosis, y | Age at death, y | Postmortem interval, h | Immunotherapy | Duration of immunotherapy, mo | Other agents | Spermatogenesis pathological diagnosis | Johnsen scoring4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late 20s | Early 30s | 2 | Ipilimumab and pembrolizumab | 4 | BRAF and MEK inhibitors | Sertoli cell only | 2 |

| 60s | 60s | 15 | Ipilimumab and nivolumab | 18 | Cyberknife radiotherapy and vemurafenib | Sertoli cell only | 2 |

| Early 30sa | 30s | NA | Ipilimumab and nivolumab | Unknown | None | Sertoli cell only | 2 |

| 50s | Late 50s | 5 | Ipilimumab and pembrolizumab | 8 | Interleukin 2 | Hypospermatogenesis | 8 |

| 60s | 60s | 17 | Ipilimumab and nivolumab | 1 | None | Hypospermatogenesis | 8 |

| Early 60s | 60s | 6 | Ipilimumab and nivolumab | 5 | None | Focal active spermatogenesis | 9 |

| 50s | Late 50s | 4 | Ipilimumab and nivolumab | 11 | Dabrafenib and trametinib | Normal spermatogenesis | 10 |

| Early 50s | Early 50s | 24 | None | None | None | Sertoli cell only | 2 |

| Late 70s | 80s | 6 | None | None | None | Sertoli cell only | 2 |

| 20s | 20s | 5 | None | None | None | Normal spermatogenesis | 10 |

| 40s | Early 50s | 5 | None | None | None | Normal spermatogenesis | 10 |

| 40s | 50s | 24 | None | None | None | Normal spermatogenesis | 10 |

| Late 60s | Late 60s | 6 | None | None | None | Normal spermatogenesis | 10 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Index patient.

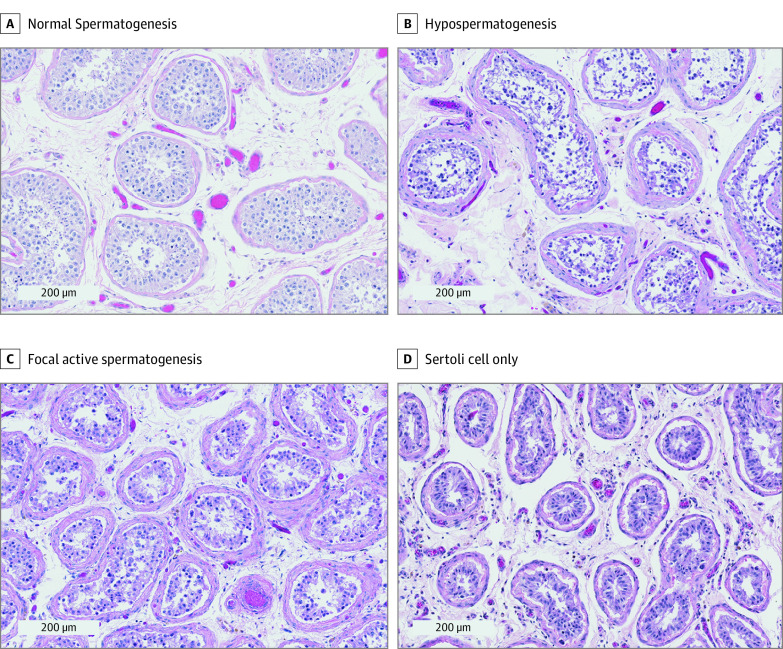

Figure. Representative Histologic Testis Images (Hematoxylin-Eosin) of Patients Who Received Immunotherapy.

A, Normal spermatogenesis. B, Hypospermatogenesis (decreased spermatogenesis at each stage including mature sperm). C, Focal active spermatogenesis (mixed pattern of seminiferous tubules in which some lack germ cells and others have complete spermatogenesis present). D, Sertoli cell only (seminiferous tubules lacking all germ cells).

Discussion

Fertility preservation is an important facet in the care of men with cancer who are within their reproductive years.5,6 One key to improving cancer survivorship and quality of life is to anticipate potential treatment-associated sequelae. Identifying the association of ICIs with future fertility will be an important step in determining whether male fertility preservation is an essential component to pretreatment counseling. A limitation of our study was the small sample size. To our knowledge, the data herein are the first to evaluate the association of ICIs with testicular function, but prospective evaluations will be essential to determining the gonadotoxic effect of ICIs.

References

- 1.Hodi FS, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma: 2-year overall survival outcomes in a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(11):1558-1568. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30366-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(19):1994-2001. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sood A, Cole D, Abdollah F, et al. Endocrine, sexual function, and infertility side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for genitourinary cancers. Curr Urol Rep. 2018;19(9):68. doi: 10.1007/s11934-018-0819-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnsen SG. Testicular biopsy score count—a method for registration of spermatogenesis in human testes: normal values and results in 335 hypogonadal males. Hormones. 1970;1(1):2-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klosky JL, Wang F, Russell KM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of sperm banking in adolescents newly diagnosed with cancer: examination of adolescent, parent, and provider factors influencing fertility preservation outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3830-3836. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopategui DM, Ibrahim E, Aballa TC, et al. Effect of a formal oncofertility program on fertility preservation rates-first year experience. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7(suppl 3):S271-S275. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.04.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]