Abstract

2,5-Diaryltetrazoles are a diverse range of compounds of considerable interest within the field of photochemistry as a valuable precursor of the nitrile imine 1,3-dipole. Current literature approaches toward this heterocycle remain unsuitable for the practical synthesis of a library of these derivatives. Herein, we disclose the development of a modular approach toward 2,5-diaryltetrazoles compatible with an array-type protocol, facilitated by a tandem Suzuki-hydrogenolysis approach.

Introduction

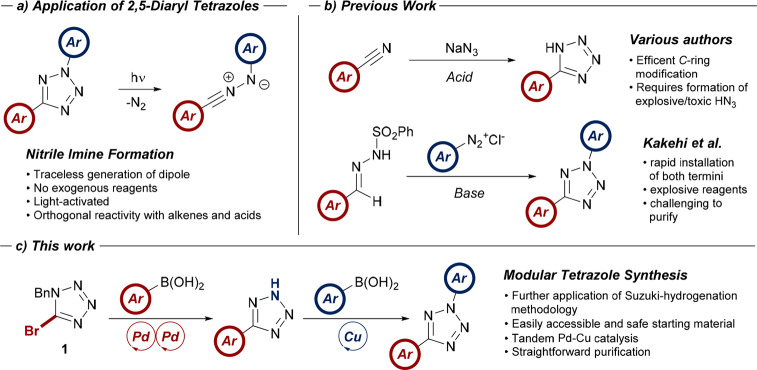

The recent resurgence of photochemistry as a unique and powerful method of forging and manipulating C–C bonds has stimulated the development and adaption of numerous synthetic protocols.1 One such transformation is the photolysis of the 2,5-diaryltetrazole moiety to yield the versatile nitrile imine 1,3-dipole (Scheme 1a).2−4 Owing to its facile reactivity with a number of functional groups including alkenes4b,5 and carboxylic acids,6 the nitrile imine has recently found widespread application in fields where an orthogonal reactivity profile (click chemistry7) is desirable, such as materials chemistry and chemical biology.8,9

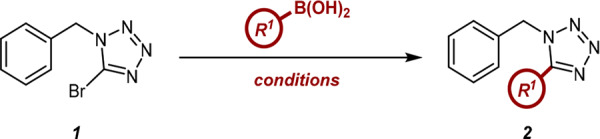

Scheme 1. (a) Application of 2,5-Tetrazoles as a Nitrile Imine Source; (b) Previous Efforts toward the Synthesis of Functionalized Tetrazoles; (c) This Work: Modular Synthesis of 2,5-Diaryltetrazoles via a Two-Step Tandem Pd and Cu Catalysis Approach.

Due to the traceless reaction profile and inherent simplicity of photolyzing tetrazole systems, this protocol has become the most common method of nitrile imine generation. However, synthetic approaches toward 2,5-tetrazoles are limited relative to the requirement for structural diversity from the corresponding dipole precursors. In our laboratories, we were interested in the synthesis of a small library of 2,5-diaryltetrazoles10 and were surprised to find that the majority of recent reports on the preparation of these compounds rely on a cycloaddition-mediated approach reported by Kakehi (Scheme 1b) over 40 years ago.11 While this robust synthesis is compatible with a range of substrates, it also typically employs hazardous reagents and often laborious purification protocols. An alternative approach was introduced by Liu in 2015; however, this route is somewhat limited by the commercial availability of the requisite aryl amidines.12 The continuing limitation in the synthesis of these heterocycles appears to be simultaneous modification of both the N- and C-aryl rings of the tetrazole. Multiple procedures for the diversification of 5-aryltetrazoles with a palette of N-aryl groups have been developed;13 however, modification of the C-aryl ring itself is primarily restricted to classical syntheses via cycloaddition between the relevant benzonitrile and hydrazoic acid (Scheme 1b).14 This approach again requires use of toxic and explosive reagents. More recently, Kamenecka disclosed a route toward 2-aryl-5-bromotetrazoles; however, this also requires the use of hazardous reagents, and subsequent derivatization to furnish C-aryl functionalized systems was not conducted.15

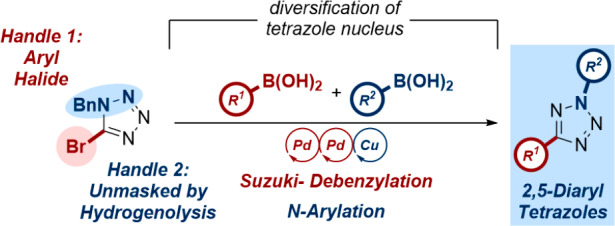

While the existing approaches are well-suited to the focused synthesis of specific 2,5-diaryltetrazole species, we found most methods incompatible with an array-type approach toward a library of such compounds. We envisioned that a common intermediate containing the preformed tetrazole nucleus encoded with chemoselective functional handles would allow for simple, rapid modification of both the 2- and 5-positions of the heterocyclic ring system.

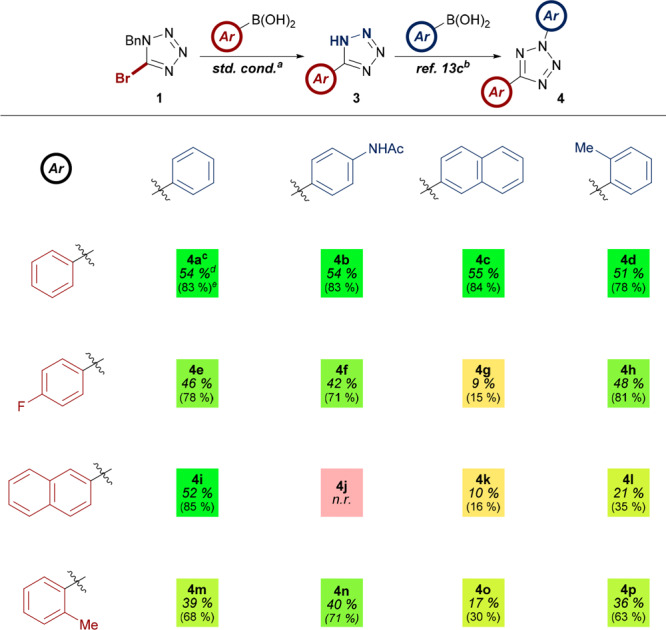

The use of 1-benzyl-5-bromotetrazole (1) as a starting material fulfilled all of the requirements discussed above for a facile and robust synthesis of tetrazole systems ready for further functionalization (Scheme 1c). Given our laboratory’s previous efforts in the development of a tandem Suzuki-hydrogenation protocol in the synthesis of sp3-rich pharmaceutical building-blocks,16 we reasoned that the treatment of 1 to similar conditions would facilitate modification of the 5-position, while simultaneously unmasking the 2-position for derivatization using existing literature methodology.13c Furthermore, 1 itself could be easily accessed on scale by alkylation and bromination of 1H-tetrazole, a commodity precursor, obviating the need for the hazardous synthesis of the heterocyclic constituent.

Results and Discussion

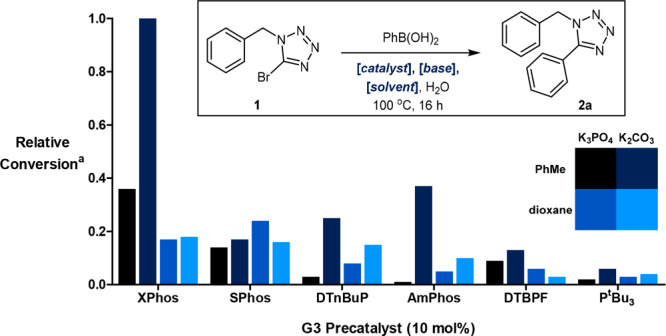

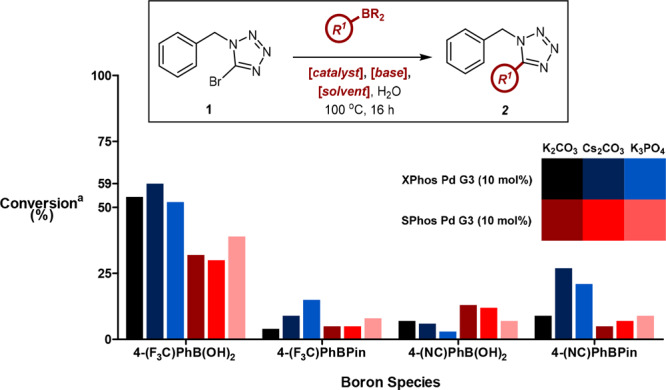

The current study commenced with the investigation of the initial Suzuki coupling between 1 and aryl boronic acids. An initial literature search identified conditions reported by Yi in the coupling of similar substrates, using Pd(PPh3)4 as a catalyst.17 As the presence of the triphenylphoshine ligand has previously been shown to be detrimental in one-pot Suzuki-hydrogenation methodology,16 we sought to identify a suitable replacement Pd complex. Our optimization campaign began with the screening of six palladium precatalysts in combination with a number of different solvents and bases (Figure 1). XPhos Pd G3 was quickly identified as a potential alternative catalyst. When employed in conjunction with toluene, these reaction conditions afforded a substantially greater conversion than all other combinations examined.

Figure 1.

Initial catalyst screening identified XPhos Pd G3 as a suitable candidate for further study. a Conversion was determined by HPLC with reference to an internal standard. All reactions were performed on a 2.5 μmol scale using 1.5 equiv of PhB(OH)2, 2 equiv of base, and a 4:1 solvent/H2O ratio (0.8 M).

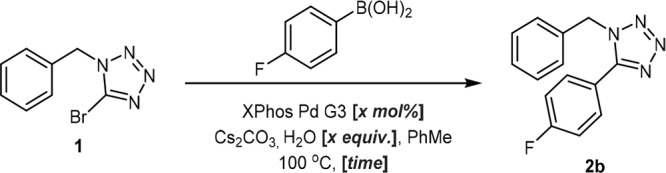

Gratifyingly, a direct comparison between the previously reported conditions and this emerging approach furnished nearly identical yields (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). Furthermore, this was accomplished over a much shorter time frame of 3 h; however, the catalyst loading remained higher. Both electron-donating and mildly electron-deficient boronic acids were shown to be compatible substrates (Table 1, entries 3 and 4); however, 4-cyanophenylboronic acid proved recalcitrant to product formation (Table 1, entry 5). In an effort to determine the compatibility of strongly electron-deficient boron species within the reaction manifold, a second screening effort was conducted, using an array of relevant variables selected based on the results of the initial screen (Figure 2). These results suggested that while the nitrile derivative remained intolerant to the reaction conditions, the improved performance of 4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenylboronic acid indicated that this issue was substrate-specific, rather than a consequence of electronic factors. Throughout this additional screen, XPhos was again shown to represent the most favorable precatalyst, while cesium was identified as the carbonate counterion.

Table 1. Direct Comparison between Established Literature Precedent and the Newly Identified Reaction Conditions.

| entry | R1 | conditions | isolated yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Ph | Pd(PPh3)4 (3 mol %), Na2CO3, PhMe, EtOH, H2O, 110 °C, 16 h17 | 75 |

| 2b | Ph | XPhos Pd G3 (10 mol %), K2CO3, PhMe, H2O, 100 °C, 3 h | 76 |

| 3b | 4-(MeO)PhB(OH)2 | as above | 72 |

| 4b | 4-(F)PhB(OH)2 | as above | 60 |

| 5b | 4-(NC)PhB(OH)2 | as above | trace |

Performed on a 1 mmol scale using 1.3 equiv of PhB(OH)2, 2 equiv of Na2CO3, and 50 equiv of H2O at a concentration of 0.1 M.

Performed on a 0.25 mmol scale using 1.5 equiv of PhB(OH)2, 2 equiv of K2CO3, and 100 equiv of H2O at a concentration of 0.1 M.

Figure 2.

Additional screen of electron-deficient boron species indicated that some substrates were compatible with the conditions, while Cs2CO3 represented a minor improvement over K2CO3. a Conversion was determined by LCMS with reference to caffeine as an internal standard. All reactions were performed on a 50 μmol scale using 1.5 equiv of PhB(OH)2, 2 equiv of base, and 50 equiv of H2O at a concentration of 0.1 M.

With optimal discrete variables in hand, we turned our attention to the catalyst loading. Preliminary efforts proved frustrating, with a significant decrease in yield observed upon reduction of catalyst loading (Table 2, entries 1–3). However, a concurrent Design of Experiments study18,19 highlighted an unanticipated correlation between the water stoichiometry of the reaction, relative to the overall concentration, and the observed conversion (Figure 3, see the Supporting Information for full details). Exploiting this finding successfully furnished the optimized reaction conditions for the Suzuki component of the proposed process, with a catalyst loading of 3 mol % (Table 2, entries 4–9).

Table 2. Minimization of Catalyst Loading through Manipulation of Water Stoichiometrya.

| entry | catalyst loading (mol %) | H2O stoichiometry (equiv) | time (h) | conversionb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 10 | 16 | 52 |

| 2 | 5 | 10 | 16 | 47 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 10 | 16 | 14 |

| 4 | 10 | 100 | 4 | 70 |

| 5 | 5 | 100 | 4 | 71 |

| 6 | 4 | 100 | 4 | 70 |

| 7 | 3 | 100 | 4 | 71 |

| 8 | 2 | 100 | 4 | 66 |

| 9 | 1 | 100 | 4 | 38 |

Reactions performed on a 50 μmol scale using 1.3 equiv of PhB(OH)2 and 1.5 equiv of Cs2CO3 at a concentration of 0.1 M.

Conversion was determined by LCMS with reference to caffeine as an internal standard.

Figure 3.

Response surface from the Design of Experiments study that revealed the importance of water stoichiometry to conversion through a secondary correlation with overall reaction concentration. See the Supporting Information for full details.

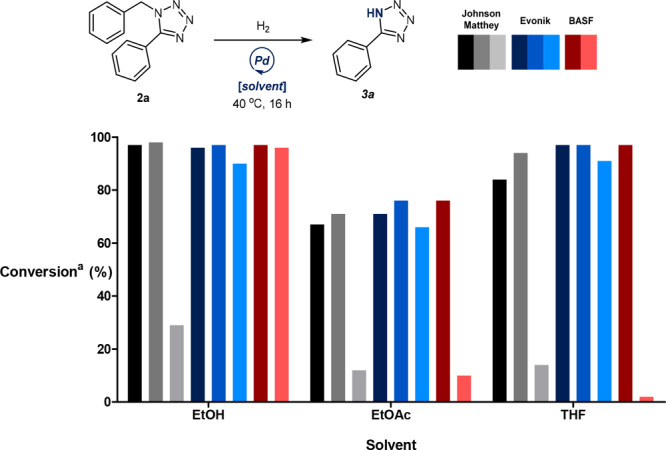

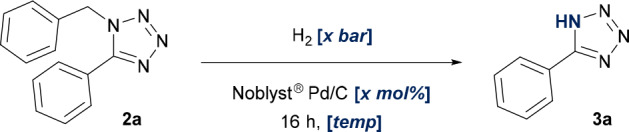

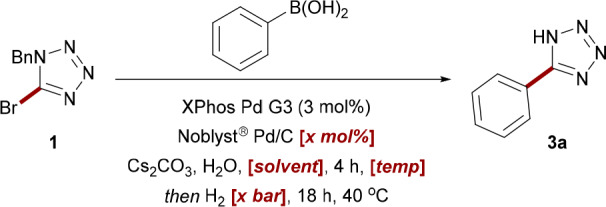

Studies into the subsequent debenzylation protocol proved to be more straightforward. A screen of eight Pd/C catalysts from three different sources afforded in many cases examples of quantitative conversion, with ethanol identified as an appropriate solvent (Figure 4). Further investigations highlighted Evonik’s Noblyst P1071 Pd/C catalyst as a desirable option to mediate the transformation (see the Supporting Information for further details). A final optimization found that a 2.5 mol % loading of catalyst facilitated quantitative conversion under only 4 bar of hydrogen gas (Table 3, entries 1–3). It was also determined that gentle heating of the reaction mixture to 40 °C was essential for enabling full conversion (Table 3, entry 4).

Figure 4.

Preliminary screening of Pd/C catalysts generated a high degree of success. (a) Conversions reported as a percentage of the total peak area of 2a and 3a. All reactions were performed on a 63 μmol scale using 6 bar of H2 and 30 wt % of Pd/C at a concentration of 0.17 M.

Table 3. Further Optimization of Hydrogenolysis Conditions.

| entry | H2 pressure (bar) | Pd/C loading (mol %) | temp (°C) | conversiond (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 6 | 7 | 40 | 97 |

| 2b | 4 | 5 | 40 | 98 |

| 3b | 4 | 2.5 | 40 | 99 |

| 4c | 4 | 2.5 | rt | 59 |

Performed on a 63 μmol scale at a concentration of 0.17 M.

Performed on a 127 μmol scale at a concentration of 0.17 M.

Performed on a 0.3 mmol scale at a concentration of 0.1 M.

Conversions were determined by LCMS with reference to caffeine as an internal standard.

Translation of this methodology into a one-pot procedure proved challenging, with preliminary attempts affording only moderate turnover. Gratifyingly, further reducing the pressure of hydrogen gas was found to increase this yield to synthetically useful levels (Table 4, entries 1 and 2). Consistent with our previous work,16 the catalyst ratio was found to be a crucial factor in maximizing product formation. While the isolated debenzylation conditions required only a 2.5 mol % Pd/C loading, any reduction below 10% Pd/C significantly impacted conversion within the one-pot manifold (Table 4, entry 3). Attempts to circumvent the addition of ethanol as a cosolvent at the midpoint of the reaction also failed to furnish improved conversions (Table 4, entries 4–6). However, satisfactory conditions were identified with a total Pd catalyst loading of 13 mol %, furnishing a 65% isolated yield of 3a in 22 h.

Table 4. Optimization of One-Pot Reaction Conditionsa.

| entry | H2 pressure (bar) | Pd/C loading (mol %) | solvent | temp (°C) | conversionb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 10 | PhMec | 100 | 43 |

| 2 | 2 | 10 | PhMec | 100 | 65 (65)d |

| 3 | 2 | 5 | PhMec | 100 | 34 |

| 4 | 2 | 10 | PhMe | 100 | 24 |

| 5 | 2 | 10 | 4:1 PhMe:nBuOH | 100 | 24 |

| 6 | 2 | 10 | 4:1 PhMe:EtOH | 70 | 37 |

Reactions performed on a 0.5 mmol scale using 1.3 equiv of PhB(OH)2, 1.5 equiv of Cs2CO3, and 100 equiv of H2O at a concentration of 0.1 M.

Conversions were determined by LCMS with reference to caffeine as an internal standard.

EtOH (2.5 mL) was added as a cosolvent prior to the hydrogenolysis step of the reaction.

Isolated yield.

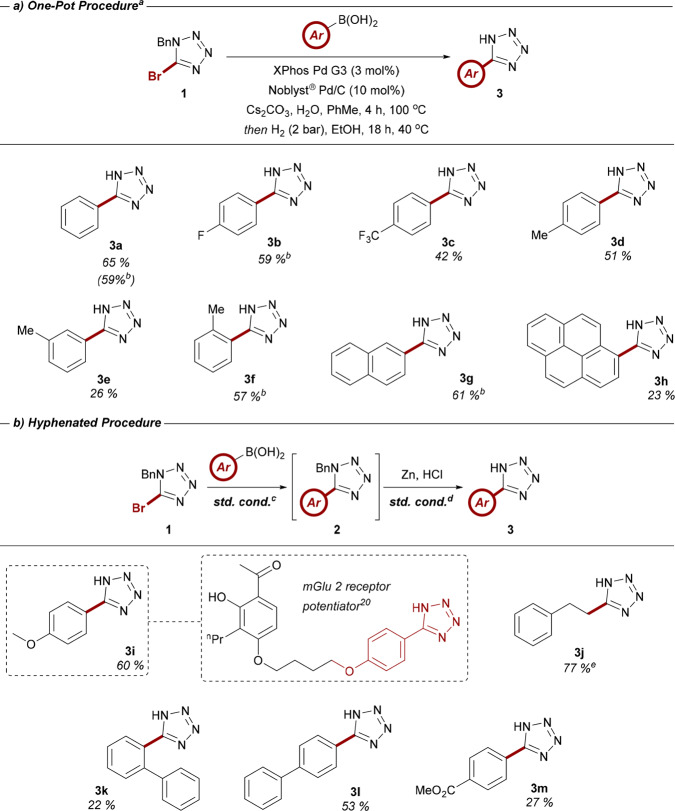

With fully optimized reaction conditions in hand, we next sought to investigate the scope of this one-pot procedure with respect to the boronic acid substituent (Table 5a). Introduction of electronically deficient and neutral moieties were found to be well-tolerated, with minimal impact on yield (cf. 3b–3d). Similarly, meta- and ortho-substitution of the aryl component was found to be compatible (cf. 3e and 3f), although the reduced yield of the meta analogue 3e remains more difficult to rationalize. More sterically encumbered substrates 3g and 3h were also successfully isolated. The modest yield associated with 3h can likely be attributed to the increased size of the tetrazole hindering adsorption of the substrate onto the surface of the Pd/C catalyst. Reaction conditions were also found to be amenable to scale-up, with substrates 3a, 3b, 3f, and 3g successfully synthesized in good yield on a 2.5 mmol scale.

Table 5. (a) Exemplar Scope of Aryl Boronic Acids Compatible with the One-Pot Suzuki-Hydrogenolysis Coupling Protocol; (b) Library of Boronic Acids Employed as Part of the Hyphenated Two-Pot Synthesis of 5-Aryltetrazoles.

Reactions performed on a 0.5 mmol scale using 1.3 equiv of boronic acid, 1.5 equiv of Cs2CO3, and 100 equiv of H2O at a concentration of 0.1 M.

2.5 mmol scale.

1 equiv of 1, 1.5 equiv of boronic acid, 2 equiv of Cs2CO3, 3 mol % of XPhos Pd G3, and 10 equiv of H2O, heated at 100 °C in a solution of PhMe (0.2 M) for 2 h.

1 equiv of 3 and 10 mol % of Noblyst Pd/C, heated at 40 °C in a solution of EtOH (0.1M) for 18 h in the presence of 2 bar H2 generated from Zn and HCl.

From (E)-styrylboronic acid.

While the one-pot generation of 5-aryltetrazoles is preferable from a practical perspective, the yields of certain substrates were found to benefit from a directly related two-pot procedure (Table 5b). This approach enabled the robust synthesis of electron-rich analogue 3i, a key pharmacophore of a reported allosteric potentiator of the metabotropic glutamate 2 receptor.20 Vinyl boronic acids were also found to be compatible, with the synthesis of 3j in good yield, providing access to alkyl tetrazole derivatives via a formal sp2–sp3 coupling. Biaryl substrates 3k and 3l represent examples of an important subset of nitrile imine precursors with extended π-systems with a diminished yield in the case of the bulkier o-phenyl species. While low-yielding, methoxy ester substrate 3m provides a valuable functional handle for further derivatization. To exhibit the versatility of this procedure, the debenzylation step of this scope exploited the ex situ generation of H2 gas in a two-chambered reaction vessel known as COware,21 attaining the required pressure of H2 without the need for more specialized apparatus.

To further exemplify the advantages afforded by this modular approach, we targeted the synthesis of a diverse matrix consisting of 16 2,5-diaryltetrazoles (Table 6). N-Aryl substituents were selected on the basis of their unique influence on the properties of the resulting heterocycle, such as the incorporation of a handle for further covalent modification (e.g., 4f) or the manipulation of λmax properties (e.g., 4k). The current approach was found to be highly effective, with the synthesis of 15 of the 16 tetrazoles accomplished in good to excellent yields in conjunction with the established copper-mediated N-arylation protocol.13c The practicality of this approach represents a significant advance over existing methods in the synthesis of a diverse library of nitrile imine precursors. One of the most beneficial aspects is the absence of time-consuming purification procedures. Owing to the acidic character of 3, appropriate moderation of pH during reaction workup afforded all 5-aryl-1H-tetrazoles at a sufficient level of purity for subsequent manipulation without the need for additional decontamination. Commencing from 5-bromotetrazole 1, the synthesis of 2,5-tetrazoles 4a–p required only one chromatographic purification step prior to the isolation of the final product. The synthesis of tetrazole 4a on a 6 mmol also demonstrated the scalability of the procedure, meaning that the entire route was shown to afford an overall yield of greater than 50% on a multimillimolar scale. The unexpected failure of substrate 4j can be perhaps be attributed to a lower thermal stability of the tetrazole due to the enhanced push–pull system generated by the substituents.22

Table 6. Synthesis of a Matrix of 2,5-Diaryltetrazoles Facilitated by Novel Suzuki-Hydrogenolysis Methodologya.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed a convenient and widely applicable Suzuki-hydrogenolysis protocol enabling the expedient synthesis of 2,5-diaryltetrazoles, valuable precursors of the nitrile imine 1,3-dipole. The scope of the reaction was shown to be tolerant of a range of steric and electronic parameters and was further expanded through the accommodation of a hyphenated, two-pot procedure. Facile synthesis of a diverse palette of 2,5-tetrazoles in combination with existing Cu-catalyzed methodology has underlined the utility of this reaction, which offers a complementary means of accessing the 2,5-diaryltetrazole scaffold in comparison to previous reports. We intend to further utilize this transformation in our continued investigations into the reactivity of the pleiotropic nitrile imine dipole.

Experimental Section

General Information

All reagents and solvents were obtained from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification unless otherwise stated. Purification was carried out according to standard laboratory methods. All reactions were conducted using round-bottom flasks or microwave vials of appropriate volume, unless otherwise stated. Reactions were carried out at elevated temperatures using a temperature-regulated hot plate/stirrer with a sand bath unless otherwise stated. Phase separation was conducted using IST Isolute Phase Separator Cartridges.

Flash chromatography was carried out manually using ZEOprep 60 HYD 40–63 μm silica gel or using a Teledyne ISCO CombiFlashRF+ apparatus with RediSep silica cartridges.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained using a PerkinElmer Spectrum One Fourier Transform spectrometer with samples used neat. 1H, 19F, and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker DRX 500, Bruker AVI, or Bruker Nano spectrometer at 400 or 500, 471 or 376, and 100 or 126 MHz, respectively. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm and coupling constants are reported in Hz with CDCl3 referenced at 7.26 (1H) and 77.16 ppm (13C) and DMSO-d6 referenced at 2.50 (1H) and 39.52 ppm (13C). Signal assignment of novel compounds was instructed using relevant 2D NMR experiments. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained on a Waters XEVO G2-XS QTof instrument (100–1200 AMU) in positive ionization mode. Reversed-phase HPLC data was obtained using a Waters CSH C18 column. LCMS spectra were obtained using an Acquity UPLC CSH C18 column (50 mm × 2.1 mm i.d. 1.7 μm packing diameter) at 40 °C. The solvents employed were a 0.1% v/v solution of formic acid in water and a 0.1% v/v solution of formic acid in acetonitrile. The UV detection was a summed signal from wavelengths 210 nm −360 nm. Mass spectral data was acquired using a Waters QDA instrument (100–1000 AMU at 5 Hz) with an alternate-scan positive and negative electrospray ionization mode.

HPLC analysis was performed using a gradient method, eluting with 5–90% MeCN/H2O over 1 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min when employing standalone HPLC, and eluting with 3–98% MeCN/H2O (+ formic acid modifier) over 2 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min when used in conjunction with MS. Reactions using an internal standard required prior HPLC calibration using samples containing varying molarities of product and caffeine, allowing calculation of the response factor by substituting values into eq 1. Screening reactions were then conducted using a known molarity of caffeine internal standard.

|

1 |

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 3a–3h

To a 10 mL Biotage Endeavor reaction vessel was added Evonik Noblyst P1071 20% palladium on carbon (10 mol %). 1-Benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (1, 1 equiv), an aryl boronic acid (1.3 equiv), and XPhos Pd G3 (3 mol %) were then added as a solution in toluene (0.1 M). To the resulting suspension was added cesium carbonate (1.5 equiv) as a solution in water (100 equiv), at which point the vessel was purged with nitrogen and stirred at 100 °C for 4 h. Upon cooling to room temperature, ethanol (50% volume of toluene) was added before the vessel was placed under a hydrogen atmosphere and heated at 40 °C for a further 18 h. Upon reaction completion, the mixture was passed through Celite and partitioned between ethyl acetate (30 mL) and water (30 mL). The organic phase was washed twice more with water (2 × 30 mL) before the aqueous phases were combined and acidified using 2 M HCl solution (20 mL). The acidic aqueous phase was then washed three times with ethyl acetate (3 × 30 mL) before all organic layers were then combined, passed through a phase separator, and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield the product.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 3i–3m

To a microwave vial containing 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (1, 1 equiv), an aryl or vinyl boronic acid (1.5 equiv), and XPhos Pd G3 (3 mol %) was added toluene (0.2 M). The vessel was purged with nitrogen, and cesium carbonate (2 equiv) and water (10 equiv) were added. The mixture was stirred at 100 °C for 2 h before being cooled to room temperature. The mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate (10 mL) and passed through a Celite plug, which was then washed with a further portion of ethyl acetate (10 mL). The solution was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by column chromatography. Isolation of the intermediate 1-benzyl-5-aryltetrazole was confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy before the species was added to chamber A of a 2 × 10 mL COware reaction vessel21a as a solution in ethanol (0.1 M). Evonik Noblyst P1071 20% palladium on carbon (10 mol %) was also added to chamber A, while chamber B was charged with zinc powder (1.8 mmol, 118 mg) and 36% hydrogen chloride solution (343 μL, 4 mmol). The vessel was sealed and stirred at 40 °C for 18 h. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, diluted with ethyl acetate (10 mL) and passed through a Celite plug, which was washed with a further portion of ethyl acetate (10 mL). This organic phase was washed twice with water (2 × 30 mL), before the aqueous phases were combined and acidified using 2 M HCl solution (20 mL). The acidic aqueous phase was then washed three times with ethyl acetate (3 × 30 mL), before all organic layers were then combined, passed through a phase separator and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield the product.

General Procedure for the N-Arylation of 5-aryltetrazoles

In accordance with previous literature precedent,13c 5-aryltetrazole (3,1 equiv), an aryl boronic acid (2 equiv), copper(I) oxide (5 mol %), and DMSO (0.13 M) were added to a microwave vial. The reaction mixture was stirred under an oxygen atmosphere at 100 °C for 16 h. The solution was cooled to room temperature and partitioned between ethyl acetate (20 mL) and 1 M HCl solution (20 mL). The aqueous layer was backwashed with an additional portion of ethyl acetate (20 mL) before the combined organic layers were combined, washed with brine (40 mL), passed through a phase separator and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was then purified by column chromatography.

Synthesis and Characterization of Compounds 2-4

1-Benzyl-5-phenyl-1H-tetrazole (2a)

To a microwave vial containing 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (60 mg, 0.25 mmol), phenylboronic acid (45.7 mg, 0.38 mmol), and XPhos Pd G3 (21.2 mg, 0.025 mmol) was added toluene (2.0 mL). The vessel was purged with nitrogen, and potassium carbonate (69.1 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added as a solution in water (0.5 mL). The mixture was stirred at 100 °C for 3 h before being cooled to room temperature. The mixture was then diluted with ethyl acetate, passed through Celite, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The obtained residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (12 g silica cartridge, 0–100% EtOAc in hexane) to give 1-benzyl-5-phenyl-1H-tetrazole (45.2 mg, 0.19 mmol, 76% yield) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.59–7.52 (m, 3H), 7.51–7.45 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.30 (m, 3H), 7.16–7.11 (m, 2H), 5.61 (s, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.8, 134.0, 131.4, 129.3, 129.2, 128.9, 128.8, 127.3, 123.9, 51.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C14H13N4 237.1140, found 237.1142. IR νmax (neat): 3065, 3033, 2937, 2857, 1529, 1497, 1458, 1401 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.17

1-Benzyl-5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (2b)

To a microwave vial containing 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (60 mg, 0.25 mmol), (4-fluorophenyl)boronic acid (52.5 mg, 0.38 mmol), and XPhos Pd G3 (21.2 mg, 0.025 mmol) was added toluene (2.5 mL). The vessel was purged with nitrogen, and potassium carbonate (69.1 mg, 0.5 mmol) and water (0.045 mL, 2.50 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred at 100 °C for 2 h before being cooled to room temperature. The mixture was then diluted with ethyl acetate, passed through Celite, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The obtained residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (12 g silica cartridge, 0–100% EtOAc in hexane) to give 1-benzyl-5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (47.9 mg, 0.15 mmol, 60% yield) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.37–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.21–7.09 (m, 4H), 5.61 (s, 2H). 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −107.44 to −107.60 (m). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.6 (d, 1JC–F = 253.2 Hz), 154.0, 133.9, 131.2 (d, 3JC–F = 8.8 Hz), 129.4, 129.0, 127.2, 120.1 (d, 4JC–F = 3.3 Hz), 116.7 (d, 2JC–F = 22.2 Hz), 51.6. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H] + calcd for C14H12FN4 255.1046, found 255.1051. IR νmax (neat): 3070, 2964, 2932, 2857, 1606, 1539, 1473, 1450 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.17

1-Benzyl-5-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-tetrazole (2c)

To a microwave vial containing 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (60 mg, 0.250 mmol), (4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)boronic acid (71.2 mg, 0.375 mmol), and XPhos Pd G3 (10.6 mg, 0.013 mmol) was added toluene (2.5 mL). The vessel was purged with nitrogen, and cesium carbonate (163 mg, 0.5 mmol) and water (0.450 mL, 25 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred at 100 °C for 6 h before being cooled to room temperature. The mixture was then diluted with ethyl acetate, passed through Celite, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The obtained residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (24 g silica cartridge, 0–100% EtOAc in hexane) to give 1-benzyl-5-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-tetrazole (43.3 mg, 0.14 mmol, 56% yield) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.77 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.39–7.35 (m, 3H), 7.17–7.13 (m, 2H), 5.64 (s, 2H). 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −63.17 (s). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.7, 133.7, 133.4 (q, 2JC–F = 33.1 Hz), 129.50, 129.45, 129.1, 127.6, 127.2, 126.3 (q, 3JC–F = 3.5 Hz), 123.6 (q, 1JC–F = 272.6 Hz), 51.8. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C15H12F3N4 305.1014, found 305.1018. IR νmax (neat): 3075, 3038, 2964, 1624, 1539, 1497, 1449, 1426 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.23

1-Benzyl-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (2i)

To a microwave vial containing 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (60 mg, 0.25 mmol), (4-methoxyphenyl)boronic acid (57.0 mg, 0.38 mmol), and XPhos Pd G3 (21.2 mg, 0.025 mmol) was added toluene (2.5 mL). The vessel was purged with nitrogen, and potassium carbonate (69.1 mg, 0.5 mmol) and water (0.045 mL, 2.50 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred at 100 °C for 2 h before being cooled to room temperature. The mixture was then diluted with ethyl acetate, passed through Celite, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The obtained residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (24 g silica cartridge, 0–100% EtOAc in hexane) to give 1-benzyl-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (48.3 mg, 0.18 mmol, 72% yield) as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.52 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.34–7.32 (m, 3H), 7.15–7.13 (m, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 5.60 (s, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.0, 154.6, 134.2, 130.5, 129.3, 128.8, 127.2, 115.9, 114.8, 55.6, 51.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C15H15ON4 267.1246, found 267.1250. IR νmax (neat): 3081, 3027, 3006, 2958, 2937, 2841, 1611, 1581, 1477, 1446 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.23

5-Phenyl-1H-tetrazole (3a)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), phenylboronic acid (79 mg, 0.65 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (53.2 mg, 50 μmol), cesium carbonate (244 mg, 0.75 mmol), water (901 μL, 50 mmol), toluene (5 mL), and ethanol (2.5 mL) to yield 5-phenyl-1H-tetrazole (47.7 mg, 0.32 mmol, 65% yield) as a white solid.

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (598 mg, 2.5 mmol), phenylboronic acid (396 mg, 3.25 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (63.5 mg, 75 μmol), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (266 mg, 250 μmol), cesium carbonate (1220 mg, 3.75 mmol), water (4.50 mL, 250 mmol), toluene (25 mL), and ethanol (12.5 mL) to yield 5-phenyl-1H-tetrazole (216 mg, 1.48 mmol, 59% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 16.84 (br. s, 1H), 8.07–8.01 (m, 2H), 7.64–7.56 (m, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 155.3, 131.2, 129.4, 126.9, 124.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C7H7N4 147.0671, found 147.0671. IR νmax (neat): 3054, 2974, 2911, 2834, 1652, 1608, 1563, 1485, 1465, 1409 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.24

5-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (3b)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (598 mg, 2.5 mmol), 4-fluorophenylboronic acid (455 mg, 3.25 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (63.5 mg, 75 μmol), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (266 mg, 250 μmol), cesium carbonate (1220 mg, 3.75 mmol), water (4.50 mL, 250 mmol), toluene (25 mL), and ethanol (12.5 mL) to yield 5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (245 mg, 1.48 mmol, 59% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 16.84 (br. s, 1H), 8.13–8.06 (m, 2H), 7.46 (app. t, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H). 19F{1H} NMR (376 MHz, DMSO) δ −108.98 (s). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 163.6 (d, 1JC–F = 249.0 Hz), 154.8, 129.4 (d, 3JC–F = 9.0 Hz), 120.9, 116.5 (d, 2JC–F = 22.3 Hz). HRMS (ESI)m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C7H6FN4 165.0576, found 165.0579. IR νmax (neat): 3070, 2985, 2916, 2841, 1609, 1498, 1446, 1410 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.25

5-(4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-tetrazole (3c)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), (4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)boronic acid (123 mg, 0.65 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (53.2 mg, 50 μmol), cesium carbonate (244 mg, 0.75 mmol), water (901 μL, 50 mmol), toluene (5 mL), and ethanol (2.5 mL) to yield 5-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-tetrazole (47.1 mg, 0.21 mmol, 42% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 17.08 (br. s, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.98 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H). 19F{1H} NMR (376 MHz, DMSO) δ −61.53 (s). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 155.3, 130.9 (q, 2JC–F = 32.1 Hz), 128.4, 127.7, 126.3, 123.8 (q, 1JC–F = 271.0 Hz). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C8H6F3N4 215.0545, found 215.0547. IR νmax (neat): 3070, 2990, 2916, 2852, 1682, 1573, 1506, 1441 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.24

5-(p-Tolyl)-1H-tetrazole (3d)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), p-tolylboronic acid (88 mg, 0.65 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (53.2 mg, 50 μmol), cesium carbonate (244 mg, 0.75 mmol), water (901 μL, 50 mmol), toluene (5 mL), and ethanol (2.5 mL) to yield 5-(p-tolyl)-1H-tetrazole (41.2 mg, 0.26 mmol, 51% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 16.71 (br. s, 1H), 7.96–7.90 (m, 2H), 7.45–7.39 (m, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 141.1, 129.9, 126.8, 121.3, 21.0, 1C not observed. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C8H9N4 161.0827, found 161.0828. IR νmax (neat): 3043, 2964, 2917, 2848, 1612, 1570, 1504, 1432, 1404 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.24

5-(m-Tolyl)-1H-tetrazole (3e)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), m-tolylboronic acid (88 mg, 0.65 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (53.2 mg, 50 μmol), cesium carbonate (244 mg, 0.75 mmol), water (901 μL, 50 mmol), toluene (5 mL), and ethanol (2.5 mL) to yield 5-(m-tolyl)-1H-tetrazole (21.3 mg, 0.13 mmol, 26% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 16.77 (br. s, 1H), 7.87 (s, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 2.41 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 155.3, 138.8, 131.8, 129.3, 127.4, 124.1, 20.9, 1C not observed. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C8H9N4 161.0827, found 161.0828. IR νmax (neat): 3065, 2980, 2918, 2847, 1651, 1599, 1560, 1485, 1456, 1415, 1400, cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.26

5-(o-Tolyl)-1H-tetrazole (3f)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (598 mg, 2.5 mmol), o-tolylboronic acid (442 mg, 3.25 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (63.5 mg, 75 μmol), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (266 mg, 250 μmol), cesium carbonate (1222 mg, 3.75 mmol), water (4.5 mL, 250 mmol), toluene (25 mL), and ethanol (12.5 mL) to yield 5-(o-tolyl)-1H-tetrazole (229 mg, 1.41 mmol, 57% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 16.63 (br. s, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.52–7.36 (m, 3H), 2.48 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 155.2, 137.1, 131.3, 130.7, 129.3, 126.2, 123.8, 20.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C8H9N4 161.0827, found 161.0827. IR νmax (neat): 3065, 3027, 2964, 2921, 2847, 2714, 1654, 1606, 1561, 1484, 1464, 1404 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.24

5-(Naphthalen-2-yl)-1H-tetrazole (3g)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (598 mg, 2.5 mmol), naphthalen-2-ylboronic acid (559 mg, 3.25 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (63.5 mg, 75 μmol), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (266 mg, 250 μmol), cesium carbonate (1222 mg, 3.75 mmol), water (4.50 mL, 50 mmol), toluene (25 mL), and ethanol (12.5 mL) to yield 5-(naphthalen-2-yl)-1H-tetrazole (331 mg, 1.53 mmol, 61% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 16.96 (br. s, 1H), 8.66 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 1H), 8.17–8.07 (m, 3H), 8.05–8.01 (m, 1H), 7.69–7.61 (m, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 133.9, 132.6, 129.2, 128.6, 127.8, 127.8, 127.2, 126.9, 123.6, 121.6, 1C not observedHRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C11H9N4 197.0827, found 197.0831. IR νmax (neat): 3128, 3059, 2990, 2921, 2889, 2841, 1635, 1609, 1564, 1510, 1417 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.24

5-(Pyren-1-yl)-1H-tetrazole (3h)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), pyren-1-ylboronic acid (160 mg, 0.65 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (53.2 mg, 50 μmol), cesium carbonate (244 mg, 0.75 mmol), water (901 μL, 50 mmol), toluene (5 mL), and ethanol (2.5 mL) to yield 5-(pyren-1-yl)-1H-tetrazole (37.6 mg, 0.11 mmol, 23% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 17.12 (br. s, 1H), 8.95 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (s, 2H), 8.44 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 8.39 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.21–8.15 (m, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 132.5, 130.7, 130.1, 129.2, 129.1, 128.8, 128.5, 128.1, 127.3, 127.2, 126.9, 126.4, 126.1, 125.0, 124.2, 124.0, 123.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C17H11N4 271.0984, found 271.0988. IR νmax (neat): 3022, 2921, 2847, 1577, 1454, 1421 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.27

5-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (3i)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), 4-methoxyphenylboronic acid (114 mg, 0.75 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), cesium carbonate (326 mg, 1.0 mmol), water (90 μL, 5.0 mmol), toluene (2.5 mL), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (36.3 mg, 34 μmol), and ethanol (2.5 mL) to yield 5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (49.4 mg, 0.28 mmol, 60% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.98 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H) 1H not observed (exchangeable). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 161.4, 128.6, 127.0, 116.3, 114.8, 55.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C8H9ON4 177.0776, found 177.0770. IR νmax (neat): 3160, 3081, 3022, 2919, 2843, 1610, 1585, 1499, 1470, 1443, 1405 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.24

5-Phenethyl-1H-tetrazole (3j)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), (E)-styrylboronic acid (111 mg, 0.75 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), cesium carbonate (326 mg, 1.0 mmol), water (90 μL, 5.0 mmol), toluene (2.5 mL), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (29.6 mg, 28 μmol), and ethanol (2.5 mL) to yield 5-phenethyl-1H-tetrazole (48.9 mg, 0.28 mmol, 77% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.07 (br. s, 1H), 7.28–7.35 (m, 2H), 7.23–7.15 (m, 3H), 3.18 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 3.06 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO) δ 155.4, 140.0, 128.4, 128.3, 126.3, 32.7, 24.6. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C9H11N4 175.0984, found 175.0977. IR νmax (neat): 3030, 3007, 2992, 2972, 2922, 2857, 1560, 1491, 1454, 1425, 1408 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.28

5-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-2-yl)-1H-tetrazole (3k)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), [1,1′-biphenyl]-2-ylboronic acid (150 mg, 0.75 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), cesium carbonate (326 mg, 1.0 mmol), water (90 μL, 5.0 mmol), toluene (2.5 mL), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (36.3 mg, 34 μmol), and ethanol (2.5 mL) to yield 5-([1,1′-biphenyl]-2-yl)-1H-tetrazole (24.1 mg, 0.11 mmol, 22% yield) as a white solid. Column chromatography (0–100% ethyl acetate in petroleum ether) following the hydrogenolysis step was required for this substrate. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.72–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.61–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.34–7.28 (m, 3H), 7.12–7.07 (m, 2H) 1H not observed (exchangeable). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 141.5, 139.2, 131.1, 130.6, 128.7, 128.2, 127.7, 127.4, 123.4, 2C not observed. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C13H11N4 223.0978, found 223.0979. IR νmax (neat): 3059, 2963, 2918, 2886, 2845, 2822, 1601, 1572, 1560, 1477, 1454, 1437 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.28

5-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-yl)-1H-tetrazole (3l)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), [1,1′-biphenyl]-4-ylboronic acid (150 mg, 0.75 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), cesium carbonate (326 mg, 1.0 mmol), water (90 μL, 5.0 mmol), toluene (2.5 mL), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (27.3 mg, 26 μmol), and ethanol (2.5 mL) to yield 5-([1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-1H-tetrazole (56.7 mg, 0.26 mmol, 53% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 8.15 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.76 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (app. t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.43–7.40 (m, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO) δ 155.0, 151.0, 142.7, 138.9, 129.1, 128.2, 127.6, 126.8, 123.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H] calcd for C13H11N4 223.0978, found 223.0979. IR νmax (neat): 3092, 3059, 3003, 2982, 2922, 2851, 1614, 1560, 1522, 1501, 1483, 1452, 1425 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.24

Methyl 4-(1H-Tetrazol-5-yl)benzoate (3m)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using 1-benzyl-5-bromo-1H-tetrazole (120 mg, 0.5 mmol), (4-(methoxycarbonyl)phenyl)boronic acid (135 mg, 0.75 mmol), XPhos Pd G3 (12.7 mg, 15 μmol), cesium carbonate (326 mg, 1.0 mmol), water (90 μL, 5.0 mmol), toluene (2.5 mL), Evonik P1071 Pd/C (10.6 mg, 10 μmol), and ethanol (1.5 mL) to yield methyl 4-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)benzoate (20.3 mg, 0.10 mmol, 27% yield) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 8.19 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 8.15 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 165.6, 155.7, 145.3, 131.5, 130.1, 127.2, 52.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C9H9N4O2 205.0720, found 205.0720. IR νmax (neat): 3154, 3098, 3073, 3046, 3019, 2953, 2928, 2855, 1709, 1686, 1566, 1499, 1427 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.28

2,5-Diphenyl-2H-tetrazole (4a)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3a (29 mg, 0.2 mmol), phenylboronic acid (49 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazole (36.7 mg, 0.17 mmol, 83% yield) as a white solid.

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3a (877 mg, 6.0 mmol), phenylboronic acid (1.5 g, 12 mmol), copper(I) oxide (43 mg, 0.3 mmol), and DMSO (10 mL) to yield 2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazole (1.2 g, 5.3 mmol, 88% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.30–8.24 (m, 2H), 8.24–8.18 (m, 2H), 7.62–7.47 (m, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.4, 137.1, 130.7, 129.8, 129.8, 129.1, 127.3, 127.2, 120.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C13H12N4 223.0984, found 223.0986. IR νmax (neat): 3066, 1595, 1530, 1497, 1470, 1447 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.29

N-(4-(5-Phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)phenyl)acetamide (4b)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3a (29 mg, 0.2 mmol), (4-acetamidophenyl)boronic acid (72 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield N-(4-(5-phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)phenyl)acetamide (49.7 mg, 0.18 mmol, 83% yield) as a brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.32 (s, 1H), 8.18–8.13 (m, 2H), 8.09 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.88 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.63–7.58 (m, 3H), 2.11 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 162.4, 156.8, 132.3, 124.3, 122.3, 120.7, 118.9, 118.4, 112.1, 112.0, 14.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C15H14N5O 280.1193, found 280.1196. IR νmax (neat): 3265, 3144, 3073, 2961, 2926, 1667, 1605, 1557, 1531, 1510, 1468, 1452, 1418 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.29

2-(Naphthalen-2-yl)-5-phenyl-2H-tetrazole (4c)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3a (29 mg, 0.2 mmol), 2-naphthylboronic acid (69 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 2-(naphthalen-2-yl)-5-phenyl-2H-tetrazole (46 mg, 0.17 mmol, 84% yield) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.65 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.34–8.28 (m, 3H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (dd, J = 6.5, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (dd, J = 6.3, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.62–7.48 (m, 5H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.4, 134.4, 133.5, 133.2, 130.7, 130.0, 129.1, 128.8, 128.1, 127.6, 127.5, 127.3, 127.2, 118.3, 118.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C17H13N4 273.1140, found 273.1143. IR νmax (neat): 3067, 3051, 2922, 1599, 1514, 1495, 1472, 1449 cm–1

5-Phenyl-2-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (4d)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3a (29 mg, 0.2 mmol), o-tolylboronic acid (54 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 5-phenyl-2-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (37 mg, 0.16 mmol, 78% yield) as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.29–8.22 (m, 2H), 7.70–7.65 (m, 1H), 7.57–7.49 (m, 3H), 7.48–7.38 (m, 3H), 2.44 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.1, 136.7, 133.3, 132.1, 130.7, 130.5, 129.1, 127.4, 127.2, 127.1, 125.4, 18.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C14H13N4 237.1140, found 237.1141. IR νmax (neat): 3051, 2959, 2920, 2853, 1585, 1530, 1497, 1468, 1450 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.13c

5-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-phenyl-2H-tetrazole (4e)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3b (39 mg, 0.24 mmol), phenylboronic acid (49 mg, 0.48 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.7 mg, 12 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 5-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-phenyl-2H-tetrazole (45 mg, 0.19 mmol, 78% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.28–8.21 (m, 2H), 8.20–8.15 (m, 2H), 7.61–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.53–7.47 (m, 1H), 7.24–7.17 (m, 2H). 19F NMR (471 MHz, CDCl3) δ −109.57 (tt, J = 8.6, 5.3 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.6, 164.4 (d, 1JC-F = 250.9 Hz), 137.0, 129.9, 129.2 (d, 3JC–F= 8.8 Hz), 123.6 (d, 4JC-F = 3.1 Hz), 120, 116.2 (d, 2JC-F = 22.0 Hz). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C13H10FN4 241.0889, found 241.0891. IR νmax (neat): 3082, 3069, 3045, 3026, 2924, 1597, 1541, 1495, 1491, 1474, 1458, 1423 cm–1. Analytical data are in agreement with the literature.30

N-(4-(5-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)phenyl)acetamide (4f)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3b (32.8 mg, 0.2 mmol), (4-acetamidophenyl)boronic acid (71.6 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 12 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield N-(4-(5-(4-fluorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)phenyl)acetamide (42 mg, 0.14 mmol, 71% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.31 (s, 1H), 8.20 (dd, J = 8.5, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.87 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (app. t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 2.10 (s, 3H). 19F NMR (471 MHz, DMSO) δ −109.54 – −109.62 (m). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.8, 163.6 (d, 1JC-F = 248.1 Hz), 163.5, 141.0, 131.0, 129.0 (d, 3JC-F = 8.8 Hz), 123.1 (d, 4JC-F = 2.9 Hz), 120.7, 119.7, 116.5 (d, 2JC–F = 22.0 Hz), 24.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C15H13FN5O 298.1099, found 298.1101. IR νmax (neat): 3310, 3277, 3208, 3150, 3088, 1665, 1609, 1541, 1508, 1466, 1423, 1414 cm–1.

5-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-(naphthalen-2-yl)-2H-tetrazole (4g)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3b (39.2 mg, 0.24 mmol), 2-naphthylboronic acid (68.8 mg, 0.42 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.7 mg, 12 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 5-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(naphthalen-2-yl)-2H-tetrazole (10 mg, 0.04 mmol, 15% yield) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.66 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.35–8.26 (m, 3H), 8.04 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.02–7.98 (m, 1H), 7.96–7.91 (m, 1H), 7.65–7.56 (m, 2H), 7.24 (dd, J = 13.6, 4.9 Hz, 2H). 19F NMR (471 MHz, CDCl3) δ −109.41 to −109.65 (m). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.7, 163.4 (d, 1JC–F = 250.8 Hz), 134.4, 133.6, 133.2, 130.1, 129.3 (d, 3JC–F = 8.6 Hz), 128.8, 128.2, 127.7, 127.6, 123.6 (d, 4JC–F = 4.2 Hz), 118.4, 118.0, 116.3 (d, 2JC–F = 22.3 Hz). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H] + calcd for C17H12FN4+ 291.1046, found 291.1046. IR νmax (neat): 3061, 2953, 2922, 2851, 1607, 1603, 1539, 1510, 1476, 1460, 1447, 1423 cm–1.

5-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (4h)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3b (32.8 mg, 0.20 mmol), o-tolylboronic acid (54 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 5-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (41.4 mg, 0.16 mmol, 81% yield) as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.27–8.21 (m, 2H), 7.66 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.50–7.37 (m, 3H), 7.25–7.18 (m, 2H), 2.43 (s, 3H). 19F NMR (471 MHz, CDCl3) δ −109.70 (tt, J = 8.6, 5.3 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.33 (d, 1JC–F = 250.7 Hz), 164.31, 136.6, 133.2, 132.1, 130.5, 129.2 (d, 3JC–F = 8.6 Hz), 127.1, 125.4, 123.7 (d, 4JC–F = 2.9 Hz), 116.3 (d, 2JC–F = 22.3 Hz), 18.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C14H12FN4+ 255.1046, found 255.1051. IR νmax (neat): 3088, 2984, 2963, 2924, 2853, 1603, 1497, 1472, 1458, 1423 cm–1

5-(Naphthalen-2-yl)-2-phenyl-2H-tetrazole (4i)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3g (39.2 mg, 0.20 mmol), phenylboronic acid (49 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 5-(naphthalen-2-yl)-2-phenyl-2H-tetrazole (46.4 mg, 0.17 mmol, 85% yield) as a beige solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.80 (s, 1H), 8.32 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.26–8.22 (m, 2H), 8.02–7.97 (m, 2H), 7.92–7.87 (m, 1H), 7.61–7.54 (m, 4H), 7.51 (app. t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.5, 137.1, 134.5, 133.4, 129.81, 129.77, 128.93, 128.87, 128.0, 127.4, 127.1, 126.9, 124.6, 124.1, 120.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C17H13N4 273.1140, found 273.1143. IR νmax (neat): 3051, 2930 2853, 1595, 1522, 1503, 1468, 1436 cm–1.

2,5-Di(naphthalen-2-yl)-2H-tetrazole (4k)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3g (39.2 mg, 0.20 mmol), 2-naphthylboronic acid (69 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 2,5-di(naphthalen-2-yl)-2H-tetrazole (10.2 mg, 0.03 mmol, 16% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.85 (s, 1H), 8.72 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 8.39 (dd, J = 4.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (dd, J = 4.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.05–7.99 (m, 3H;), 7.97–7.90 (m, 2H;), 7.66–7.55 (m, 4H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.6, 134.6, 134.5, 133.6, 133.4, 133.3, 130.1, 129.0, 128.9, 128.85, 128.2, 128.1, 127.7, 127.6, 127.4, 127.2, 126.9, 124.6, 124.2, 118.5, 118.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C21H15N4 323.1297, found 323.1299. IR νmax (neat): 3055, 3030, 1630, 1603, 1524, 1501, 1474, 1437 cm–1

5-(Naphthalen-2-yl)-2-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (4l)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3g (39.2 mg, 0.20 mmol), o-tolylboronic acid (54 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 5-(naphthalen-2-yl)-2-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (20.0 mg, 0.07 mmol, 35% yield) as a beige solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.80 (s, 1H), 8.32 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.00–7.97 (m, 1H), 7.93–7.88 (m, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.51–7.39 (m, 3H), 2.47 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.2, 136.7, 134.5, 133.4, 133.3, 132.1, 130.5, 129.0, 128.9, 128.0, 127.3, 127.07, 127.05, 126.9, 125.4, 124.7, 124.1, 19.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C18H15N4 287.1297, found 287.1299. IR νmax (neat): 3061, 2924, 2853, 1605, 1522, 1493, 1464, 1435 cm–1

2-Phenyl-5-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (4m)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3f (32.0 mg, 0.20 mmol), phenylboronic acid (49 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 2-phenyl-5-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (32.0 mg, 0.14 mmol, 68% yield) as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 8.19–8.13 (m, 2H), 8.04 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.73–7.66 (m, 2H), 7.64–7.59 (m, 1H), 7.50–7.36 (m, 3H), 2.64 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 164.9, 137.0, 136.2, 131.5, 130.4, 130.1, 129.2, 126.3, 125.6, 119.9, 21.2, 1C not observed. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C14H13N4 237.1135, found 237.1134. IR νmax (neat): 3076, 3030, 2980, 2959, 2926, 1595, 1522, 1497, 1479, 1456, 1418 cm–1.

N-(4-(5-(o-Tolyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)phenyl)acetamide (4n)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3f (32.0 mg, 0.20 mmol), (4-acetamidophenyl)boronic acid (71.6 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield N-(4-(5-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)phenyl)acetamide (41.2 mg, 0.14 mmol, 71% yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.17–8.13 (m, 2H), 8.13–8.09 (m, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (br. s, 1H), 7.43–7.31 (m, 3H), 2.71 (s, 3H), 2.23 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.6, 165.7, 139.3, 137.8, 133.0, 131.6, 130.3, 129.7, 126.3, 126.2, 120.7, 120.5, 24.8, 21.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H16N5O 294.1349, found 294.1351. IR νmax (neat): 3294, 3269, 3211, 3148, 3075, 2957, 2926, 1661, 1611, 1535, 1510, 1481, 1450, 1414 cm–1

2-(Naphthalen-2-yl)-5-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (4o)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3f (32.0 mg, 0.20 mmol), 2-naphthylboronic acid (69 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 2-(naphthalen-2-yl)-5-(o-tolyl)-2H-tetrazole (17.3 mg, 0.06 mmol, 30% yield) as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.68 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, 8.35 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.03–7.99 (m, 1H), 7.97–7.91 (m, 1H), 7.65–7.57 (m, 2H), 7.45–7.35 (m, 3H), 2.77 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.9, 137.9, 134.5, 133.5, 133.3, 131.6, 130.3, 130.1, 129.8, 128.8, 128.2, 127.7, 127.5, 126.4, 126.3, 118.3, 118.0, 22.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C18H15N4 287.1291, found 287.1288. IR νmax (neat): 3049, 3034, 2959, 2922, 2851, 1603, 1514, 1474, 1449 cm–1.

2,5-Di-o-tolyl-2H-tetrazole (4p)

Synthesized in accordance with the general procedure using tetrazole 3f (32.0 mg, 0.20 mmol), o-tolylboronic acid (54 mg, 0.4 mmol), copper(I) oxide (1.4 mg, 10 μmol), and DMSO (2 mL) to yield 2,5-di-o-tolyl-2H-tetrazole (31.4 mg, 0.13 mmol, 63% yield) as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.19–8.16 (m, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.49–7.34 (m, 6H), 2.72 (s, 3H), 2.47 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.4, 137.7, 136.7, 133.0, 132.1, 131.6, 130.3, 130.2, 129.7, 127.1, 126.4, 126.2, 125.3, 22.0, 19.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C15H15N4 251.1291, found 251.1290. IR νmax (neat): 3063, 3032, 2961, 2924, 1607, 1584, 1520, 1495, 1476, 1452 cm–1

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support of GlaxoSmithKline and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/P51066X/1). We thank Evonik Industries for their gift of 10 g of Noblyst P1071 Pd/C catalyst for substrate scope studies and GlaxoSmithKline Stevenage for the use of their high-throughput catalysis screening platform.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.0c00807.

General procedures, optimization experiments, and the NMR spectra of selected compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Prier C. K.; Rankic D. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322. 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Romero N. A.; Nicewicz D. A. Organic Photoredox Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10075. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Metternich J. B.; Gilmour R. Photocatalytic E → Z Isomerization of Alkenes. Synlett 2016, 27, 2541. 10.1055/s-0036-1588621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Huisgen R.; Seidel M.; Sauer J.; McFarland J.; Wallbillich G. The Formation of Nitrile Imines in the Thermal Breakdown of 2,5-Disubstituted Tetrazoles. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24, 892. 10.1021/jo01088a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Sieber W.; Gilgen P.; Chaloupka S.; Hansen H. J.; Schmid H. Tieftemperaturbestrahlungen von 3-Phenyl-2H-azirinen. Helv. Chim. Acta 1973, 56, 1679. 10.1002/hlca.19730560525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Meier H.; Heinzelmann W.; Heimgartner H. Direct Detection of Diphenylnitrilimine in the Photolysis of 2, 5- Diphenyltetrazole. Chimia 1980, 34, 504. [Google Scholar]; d Meier H.; Heinzelmann W.; Heimgartner H. Inter- and Intramolecular Trapping Reactions of Photochemically Generated Diarylnitrilimines. Chimia 1980, 34, 506. [Google Scholar]; e Toubro N. H.; Holm A. Nitrilimines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 2093. 10.1021/ja00526a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Sicard G.; Baceiredo A.; Bertrand G. Synthesis and Reactivity of a Stable Nitrile Imine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 2663. 10.1021/ja00216a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Huisgen R. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions: Past and Future. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1963, 2, 565. 10.1002/anie.196305651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Bertrand G.; Wentrup C. Nitrile Imines: From Matrix Characterization to Stable Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1994, 33, 527. 10.1002/anie.199405271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Clovis J. S.; Eckell A.; Huisgen R.; Sustmann R. 1.3-Dipolare Cycloadditionen, XXV: Der Nachweis des freien Diphenylnitrilimins als Zwischenstufe bei Cycloadditionen. Chem. Ber. 1967, 100, 60. 10.1002/cber.19671000108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wang Y.; Claudia A.; Rivera Vera I.; Lin Q. Convenient Synthesis of Highly Functionalized Pyrazolines via Mild, Photoactivated 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 4155. 10.1021/ol7017328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Blasco E.; Sugawara Y.; Lederhose P.; Blinco J. P.; Kelterer A. M.; Barner-Kowollik C. Understanding Reactivity Patterns in Light-Induced Nitrile Imine Mediated Tetrazole-Ene Cycloadditions. ChemPhotoChem. 2017, 1, 159. 10.1002/cptc.201600042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Menzel J. P.; Noble B. B.; Lauer A.; Coote M. L.; Blinco J. P.; Barner-Kowollik C. Wavelength Dependence of Light-Induced Cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15812. 10.1021/jacs.7b08047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples, see:; a Huisgen R.; Seidel M.; Wallbillich G.; Knupfer H. Diphenyl-nitrilimin und seine 1.3-Dipolaren Additionen an Alkene und Alkine. Tetrahedron 1962, 17, 3. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)99001-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b George M.; Angadiyavar C. S. Photochemical Cycloadditions of 1,3-Dipolar Systems. I: Additions of NC-Diphenylsydnone and 2,5-Diphenyltetrazole. J. Org. Chem. 1971, 36, 1589. 10.1021/jo00811a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Moody C.; Rees C.; Young R. Synthesis of 3-phenylpyrazoles from 2-alkenyl-5-phenytetrazoles. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1991, 2, 329. 10.1039/p19910000329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Pla D.; Tan D. S.; Gin D. Y. 5-(Methylthio)tetrazoles as Versatile Synthons in the Stereoselective Synthesis of Polycyclic Pyrazolines via Photoinduced Intramolecular Nitrile Imine–Alkene 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 2407. 10.1039/C4SC00107A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Huisgen R.; Sauer J.; Seidel M. Ringöffnungen der Azole, VI: Die Thermolyse 2.5-disubstituierter Tetrazole zu Nitriliminen. Chem. Ber. 1961, 94, 2503. 10.1002/cber.19610940926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li Z.; Qian L.; Li L.; Bernhammer J. C.; Huynh H. V.; Lee J. S.; Yao Q. S. Tetrazole Photoclick Chemistry: Reinvestigating Its Suitability as a Bioorthogonal Reaction and Potential Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2002. 10.1002/anie.201508104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhao S.; Dai J.; Hu M.; Liu C.; Meng R.; Liu X.; Wang C.; Luo T. Photo-Induced Coupling Reactions of Tetrazoles with Carboxylic Acids in Aqueous Solution: Application in Protein Labelling. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4702. 10.1039/C5CC10445A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. C.; Finn M. G.; Sharpless K. B. Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples, see:; a Kamber D. N.; Nazarova L. A.; Liang Y.; Lopez S. A.; Patterson D. M.; Shih H. W.; Houk K. N.; Prescher J. A. Isomeric Cyclopropenes Exhibit Unique Bioorthogonal Reactivities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13680. 10.1021/ja407737d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Madden M. M.; Muppidi A.; Li Z.; Li X.; Chen J.; Lin Q. Synthesis of Cell-Permeable Stapled Peptide Dual Inhibitors of the p53-Mdm2/Mdmx Interactions via Photoinduced Cycloaddition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 1472. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c An P.; Lewandowski T. M.; Lin Q. Design and Synthesis of a BODIPY-Tetrazole Based “Off-On” in-Cell Fluorescence Reporter of Hydrogen Peroxide. ChemBioChem 2018, 19, 1326. 10.1002/cbic.201700656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Herner A.; Marjanovic J.; Lewandowski T. M.; Marin V.; Patterson M.; Miesbauer L.; Ready D.; Williams J.; Vasudevan A.; Lin Q. 2-Aryl-5-carboxytetrazole as a New Photoaffinity Label for Drug Target Identification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14609. 10.1021/jacs.6b06645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Heiler C.; Offenloch J. T.; Blasco E.; Barner-Kowollik C. Photochemically Induced Folding of Single Chain Polymer Nanoparticles in Water. ACS Macro Lett. 2017, 6, 56. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.6b00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Konrad W.; Fengler C.; Putwa S.; Barner-Kowollik C. Protection-Group-Free Synthesis of Sequence-Defined Macromolecules via Precision λ-Orthogonal Photochemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 7133. 10.1002/anie.201901933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Buten C.; Lamping S.; Körsgen M.; Arlinghaus H. F.; Jamieson C.; Ravoo B. J. Surface Functionalization with Carboxylic Acids by Photochemical Microcontact Printing and Tetrazole Chemistry. Langmuir 2018, 34, 2132. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b03678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Delafresnaye L.; Zaquen N.; Kuchel R. P.; Blinco J. P.; Zetterlund P. B.; Barner-Kowollik C. A Simple and Versatile Pathway for the Synthesis of Visible Light Photoreactive Nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1800342. 10.1002/adfm.201800342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ramil C. P.; Lin Q. Photoclick Chemistry: a Fluorogenic Light-Triggered in vivo Ligation Reaction. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 89. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Delaittre G.; Goldmann A. S.; Barner-Kowollik C. Efficient Photochemical Approaches for Spatially Resolved Surface Functionalization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 11388. 10.1002/anie.201504920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone K.; Bertrand S.; Mowat J.; Jamieson C. Metal-free C–C Bond Formation via Coupling of Nitrile Imines and Boronic Acids. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 10412. 10.1039/C9SC03032H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ito S.; Tanaka Y.; Kakehi A. Synthesis of 2,5-Diaryltetrazoles from N-Phenylsulfonylbenzhydrazidoyl Chlorides and Arylhydrazines. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1976, 49, 762. 10.1246/bcsj.49.762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ito S.; Tanaka Y.; Kakehi A.; Kondo K. A Facile Synthesis of 2,5-Disubstituted Tetrazoles by the Reaction of Phenylsulfonylhydrazones with Arenediazonium Salts. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1976, 49, 1920. 10.1246/bcsj.49.1920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan M.; Wang Y. H.; Liu S. T. One-Pot Reactions for Synthesis of 2,5-Substituted Tetrazoles from Aryldiazonium Salts and Amidines. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5886. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples, see:; a Fedorov A. Y.; Finet J. P. N-Phenylation of Azole Derivatives by Triphenylbismuth Derivatives/Cupric Acetate. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 2747. 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00287-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Beletskaya I. P.; Davydov D. V.; Gorovoy M. S. Palladium- and Copper-Catalyzed Selective Arylation of 5-Aryltetrazoles by Diaryliodonium Salts. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 6221. 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)01325-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Li Y.; Gao L. X.; Han F. S. Efficient Synthesis of 2,5-Disubstituted Tetrazoles via the Cu2O-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidative Direct Cross-Coupling of N–H free Tetrazoles with Boronic Acids. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2719. 10.1039/c2cc17894j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Onaka T.; Umemoto H.; Miki Y.; Nakamura A.; Maegawa T. [Cu(OH)(TMEDA)]2Cl2-Catalyzed Regioselective 2-Arylation of 5-Substituted Tetrazoles with Boronic Acids under Mild Conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6703. 10.1021/jo500862t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh J.; Vávrová K.; Hrabálek A. Synthesis and Functionalization of 5-Substituted Tetrazoles. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2012, 6101. 10.1002/ejoc.201200469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; See also references cited therein.

- Patouret R.; Kamenecka T. M. Synthesis of 2-aryl-2H-tetrazoles via a Regioselective [3 + 2] Cycloaddition Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1597. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.02.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P. S.; Jamieson C.; Simpson I.; Watson A. J. B. Practical Synthesis of Pharmaceutically Relevant Molecules Enriched in sp3 Character. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 46. 10.1039/C7CC08670A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi K. Y.; Yoo S. Synthesis of 5-Aryl and Vinyl Tetrazoles by the Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 1679. 10.1016/0040-4039(95)00129-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson R.; Carlson J. E.. Design and Optimization in Organic Synthesis, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stat-Ease Design Expert v8; http://www.statease.com/.

- Pinkerton A. B.; Vernier J. M.; Schaffhauser H.; Rowe B. A.; Campbell U. C.; Rodriguez D. E.; Lorrain D. S.; Baccei C. S.; Daggett L. P.; Bristow L. J. Phenyl-Tetrazolyl Acetophenones: Discovery of Positive Allosteric Potentiatiors for the Metabotropic Glutamate 2 Receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 4595. 10.1021/jm040088h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Friis S. D.; Lindhardt A. T.; Skrydstrup T. The Development and Application of Two-Chamber Reactors and Carbon Monoxide Precursors for Safe Carbonylation Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 594. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Clohessy T. A.; Roberts A.; Manas E. S.; Patel V. K.; Anderson N. A.; Watson A. J. B. Chemoselective One-Pot Synthesis of Functionalized Amino-azaheterocycles Enabled by COware. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6368. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S. Y.; Baldwin J. E. Cycloadditions XIX: Kinetics of the Thermal Decomposition of 2,5-Diaryltetrazoles. Tetrahedron 1968, 24, 3787. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)92586-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aridoss G.; Laali K. K. Highly Efficient Synthesis of 5-Substituted 1H-Tetrazoles Catalyzed by Cu–Zn Alloy Nanopowder, Conversion into 1,5- and 2,5-Disubstituted Tetrazoles, and Synthesis and NMR Studies of New Tetrazolium Ionic Liquids. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 6343. 10.1002/ejoc.201100957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vignesh A.; Bhuvanesh N. S. P.; Dharmaraj N. Conversion of Arylboronic Acids to Tetrazoles Catalyzed by ONO Pincer-Type Palladium Complex. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 887. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan Chakraborty R.; Ghosh P. TiCl3 Catalyzed One-Pot Protocol for the Conversion of Aldehydes into 5-substituted 1H-Tetrazole. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 3616. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.08.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M. S.; Cheng X.; Chen Y. G.; Wu X. X.; Qu G. R.; Guo H. M. Efficient Synthesis of Tetrazole Hemiaminal Silyl Ethers via Three-Component Hemiaminal Silylation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 6890. 10.1039/C8OB02089B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bag S. S.; Talukdar S.; Anjali S. J. Regioselective and Stereoselective Route to N2-β-tetrazolyl Unnatural Nucleosides via SN2 Reaction at the Anomeric Center of Hoffer’s Chlorosugar. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 2044. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara K.; Kawashima M.; Shioiri T.; Matsugi M. Synthesis of 5-Substituted 1H-Tetrazoles from Aldoximes Using Diphenyl Phosphorazidate. Synlett 2016, 27, 2225. 10.1055/s-0035-1561668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S.; Harris R.; Jamieson C. Regiospecific Synthesis of N2-Aryl 1,2,3-Triazoles from 2,5-Disubstituted Tetrazoles via Photochemically Generated Nitrile Imine Intermediates. Synlett 2014, 25, 2480. 10.1055/s-0034-1379010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse V.; Leihkauf P.; Csongar C.; Tomaschewski G. Photochemistry of Diarylsubstituted 2H-Tetrazoles VI: Quantum Yields of the Photolysis of Diarylsubstituted 2H-Tetrazoles. J. Prakt. Chem. 1988, 330, 406. 10.1002/prac.19883300310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.