Abstract

Aside from their roles in hemostasis and thrombosis, thrombocytes or platelets also promote tumor growth via immune suppression. However, the extent to which platelet activation shapes the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) and whether platelet inhibition can be leveraged to improve checkpoint blockade is unknown. We show here that platelet function in mice mediates suppression of CD8+ T cell function within TME but not in the draining lymph nodes. Tempering platelet activation genetically reduced TGF-β signaling in both immune and non-immune cells in TME, enhanced T cell frequency and function, and decreased CD11b+ myeloid cell infiltration in the tumor. Targeting platelet function pharmacologically in tumor-bearing mice with aspirin and clopidogrel in combination with PD-1 blockade improved tumor control. These results suggest that platelet function represents a continuous, supplemental mechanism of immune evasion co-opted by tumors to evade anti-tumor immunity and offers an attractive target for combination with immunotherapy.

Introduction

Platelets, known primarily for their role in hemostasis and wound healing, have recently been shown to promote primary tumor growth via immune suppression (1). We have previously reported a genetic model for platelet dysfunction by deleting the heat shock protein gp96 specifically from the megakaryocyte compartment. These mice (Pf4-cre Hsp90b1Flox/Flox herein referred to as Plt-gp96 KO) exhibit severe thrombocytopenia coupled with platelet dysfunction due to loss of surface expression of the GPIb-IX-V complex, the primary receptor for von Willebrand Factor (2). Although this interaction is a predominant mechanism by which platelet activation occurs in vivo, factors such as ADP, thromboxane A2, or thrombin can mediate platelet activation alternative to this pathway (3). We previously reported that Plt-gp96 KO mice have enhanced tumor control in an adoptive T cell transfer (ACT) model of melanoma (1). These results were recapitulated using readily available antiplatelet agents aspirin and clopidogrel. However, as the adoptively transferred T cells in this setting were optimally primed with IL-12 ex vivo, the extent to which this phenomon is generalizable into a situation where the immune response to cancer is host-mediated has yet to be investigated.

Immune evasion is a necessary characteristic for the survival and dissemination of neoplastic growth. A predominant mechanism by which cancers avoid immune detection is through the induction of a hypo-responsive T cell state, referred to as T cell exhaustion. This involves ligation of program death receptor 1 (PD-1) on T cells by its cognate ligand, programmed death ligand ½ (PD-L½) (4). While pharmacologic inhibition of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis restores T cell functionality and has demonstrated meaningful therapeutic response in a litany of cancer indications, single agent therapy does not result in a uniform, durable benefit (5). One avenue for improving patient outcomes is a combination-based intervention strategy where a PD-1/PD-L1 blocking antibody is combined with another treatment modality (6). Exposure to immunosuppressive cell type such as macrophages or cytokines like TGF-β1, in conjunction with the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, can coordinate suppression via non-redundant pathways. This increases the likelihood of tumor survival even in the presence of checkpoint blockade (7–9). Thus, intervention strategies that modulate the TME are of extreme interest given their potential for combination with a PD-1/PD-L1 backbone (10). We report here that platelet activation represents a secondary mechanism of immune evasion in situ that continuously shapes the TME to promote immune suppression. Furthermore, pretreating established tumors with an antiplatelet therapy regimen enhanced responsiveness to PD-1 blockade.

Methods

Mice

Platelet-specific Hsp90b1 knockout (KO) mice were generated by crossing Hsp90b1Flox/Flox mice with Pf4-cre mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All experiments involving Pf4-cre (+) Hsp90b1 Flox/Flox used Pf4-cre (−) Hsp90b1 Flox/Flox littermates as wild type controls. Six to eight weeks old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Female mice were used for all experiments except for MB-49 tumor experiments. All animals were maintained in a specific pathogen free environment and experiments were conducted under approved protocols by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Tumor Model

MC-38 murine colon adenocarcinoma and MB-49 bladder cancer cells were gifted from Dr. Jessica Thaxton (MUSC) and Dr. Christina Volkel Johnson (MUSC), respectively. Cells were cultured with DMEM-12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep and Plasmocin mycoplasma prophylactic (Invitrogen). AP Therapy consisted of 150 mg/L aspirin (Sigma) delivered continously in the drinking water and oral gavage of 30 mg/kg body weight clopidogrel (MUSC internal pharmacy). Clopidogrel was delivered every other day expect for combination experiments with PD-1 in which it was delivered daily form day 5 to day 9, after which it was returned to every other day. For platelet depletion experimets, mice were injected with rabbit anti-mouse thrombocyte serum (Cedarlane) or control rabbit serum daily for 4 dyas (1:10, 300μL per mouse i.p.). For CD8+ T cell depletion experiments, mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 200 μg of anti-mouse CD8 neutralizing antibody (BioXcell, clone 53–6.7) on day −1 and 100 μg every three days thereafter. For checkpoint blockade experiments, 100 μg of anti-mouse PD-1 antibody (BioXCell, Clone 29F.1A12) was administered i.p. to appropriate groups starting on day 9, and every 3 days thereafter, for a total of 6 cycles. Tumor surface area (width x length) was measured 3–5 times per week starting on day 5 post implantation with electronic calipers.

Platelet Purification and Complete Blood Count (CBC)

Peripheral blood was collected in tubes containing 0.5 mL of Acid Citrate Dextrose (ACD) Buffer [39 mM citric acid, 75 mM sodium citrate, 135 mM dextrose, and prostaglandin E1 (1 μg/ml) (pH 7.4)]. Samples were centrifuged at 100 g for 10 min with no break and the upper buffy coat layer of platelet-rich plasma was collected for flow cytometric analysis. For platelet counts, blood was collected in K2EDTA coated microfuge tubes (Milian) and a complete blood count was performed using an animal blood counter (Animal Care Company).

Flow Cytometry

For analysis of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TILs), tumors were harvested and subjected to mechanical and enzymatic digestion with collagenase D (Roche, 2 mg/mL), DNase (Sigma, 100 μg/mL) and Dispase (0.005 U/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C on shake at 125 RPM. Samples were stained with eFluor506 fixable viability dye (Invitrogen), extracellular surface markers and FcR block concurrently for 30 min on ice. For cytokine production experiments, samples were stimulated in a 96-well plate for 4 h at 37°C in the presence of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (500 ng/ml), ionomycin (1 μg/ml) and Brefeldin A. All intracellular staining was performed using the Foxp3 transcription factor staining kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were acquired on the BD FACSVerse and analysis was performed using FlowJo v10.3.0 (Tree Star).

Multispectral Imaging

Immunofluorescence multiplex staining was performed using Opal Fluorophore Reagents (Akoya Bioscience) and run on a Discovery Ultra System (Ventana Medical Systems). FFPE tissues were cut in 4–5 μm thick sections and placed on plus charged slides. Antigen retrieval was performed in EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) at 95°C for 32 minutes. Slides were washed then blocked in 3% H2O2. Antibodies were stained in the following sequential fashion starting with the primary antibodies, then an OmniMap anti-Rb HRP or OmniMap anti-Rat HRP (Roche Tissue Diagnostics) and finally an Opal TSA Plus (Akoya Biosciences). Slides were stripped after each sequence with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 90°C for 8–16 minutes before staining with the next antibody. Primaries included pSMAD3 (1:500, ab52903, Abcam) Opal 520 TSA Plus, CD45 (1:100, #70257, Cell Signaling Technology), Opal 620 TSA Plus, PLVAP/PV-1 (MECA-32, 1:100, ab27852, Abcam) Opal 690 TSA plus. Nuclei were subsequently visualized with DAPI, and the section was coverslipped using ProLong™ Diamond Antifade Mountant (ThermoFisher). Slides were imaged using the Vectra® Polaris™ (Akoya Bioscience) automated quantitative pathology imaging system and analyzed with the Inform® software.

Statistical Analysis

For comparisons between two groups for a single variable a student’s t test was employed. In the case of unequal variance between groups based on an F-test, the data was analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test. For comparisons between three or more groups a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison correction was used. Tumor growth curves were analyzed via two-way repeated measures ANOVA. Two tailed α < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

Enhanced platelet function promotes TGF-β signaling which alters the frequency of tumor infiltrating lymphocyte populations

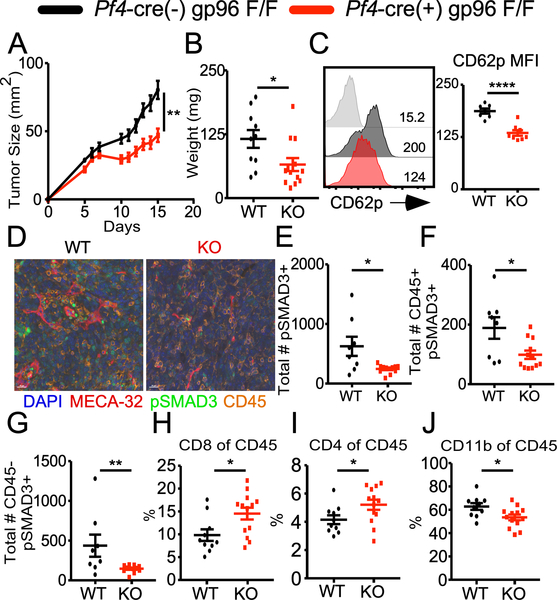

To investigate the role of platelet function in shaping the TME, we compared the growth of MC-38 colon cancer cells in wild type (WT) mice versus Plt-gp96 KO mice. We chose this model as the immunogenicity of the MC-38 cell line is well established (11). Moreover, extensive work has detailed the PD-1/PD-L1 axis as the primary mechanism of immune evasion in the MC-38 model (12) and multiple reports have demonstrated that alterations to various aspects of immunosuppressive cells in the TME were capable of diminishing tumor growth (13, 14). WT mice and Plt-gp96 KO littermate controls were challenged on the right flank and tumor growth was monitored. The Plt-gp96 KO mice displayed significantly slower tumor growth as compared to littermate controls (Fig. 1A, 1B), which translated to improved long term tumor control and survival (data not shown). Plt-gp96 KO mice also demonstrated decreased systemic platelet activation compared to WT mice as measured by CD62p expression (Fig. 1C). This was directly related to the tumor as there was no difference in CD62p between tumor-free WT and Plt-gp96 KO mice (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Further characterization via flow cytometry of WT and Plt-gp96 KO mice turned up minimal to no differences in expression of other proteins involved in platelet function such as CD61, CD41, CD40 CD40L (Supplemental Fig 1B-D). These findings suggest that tumor induced platelet activation in vivo is at least partially dependent on surface expression of GpIb-IX-V. Furthermore, significant protection was also observed with another syngeneic tumor model, MB-49 bladder cancer (Supplemental Fig. 2). These data unequivocally demonstrate that platelet activation promotes tumor growth.

FIGURE 1.

Platelet function controls TGF-β signaling and alters the frequency of tumor infiltrating immune populations. (A) MC-38 colon cancer cells (1×106) tumor growth over 15 days. (B) Day 15 tumor weight of mice depicted in (A). (C) CD62p expression on purified platelets from Day 14 tumor bearing WT or Plt-gp96 KO mice; grey histogram represents the isotype control. (D) Mutliplex imaging of day 15 tumors from WT or Plt-gp96 KO mice; DAPI (blue), MECA-32 (red), pSMAD3(green), CD45 (orange). (E) Absolute number of pSAMD3+ cells based on the total number of nuclei. (F) Absolute number of pSMAD3+ nuclei colocalized with CD45+ staining. (G) Absolute number of pSMAD3+ nuclei that are CD45-. (H) Frequency of CD8+ T cells gated on live CD45+ cells. (I) Frequency of CD4+ T cells gated on live CD45+ cells. (J) Frequency of CD3- CD11b+ myeloid cells gated on live CD45+. (A-B, H-J) N = 10–13 females per group. (C) N = 7–8 females per group. (D-G) N = 8–12 females per group. All data are displayed as mean +/− SEM. (A-C, H-J) representative data from 2–3 independent experiments. (D-G) compiled data from 2–5 representative fields of interest per sample, 1 independent experiment. A) Repeated measures two-way ANOVA, ** p < 0.01. (B-C, H-J) Student’s t test, * p < 0.05, **** p < 0.0001. (D-G) Mann-Whitney U test, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

We next utilized the Plt-gp96 KO mice to discern the molecular mechanism of platelet-mediated immune suppression, given gp96 is also an obligate chaperone required for surface expression of TGF-β docking and activating receptor GARP (15). This is important because surface GARP expression is significantly elevated following platelet activation, linking the local bioavailabity of TGF-β to platelet function (16). Using multi-spectrum histology and quantitative imaging analysis, we noted a significant decrease in the amount of TGF-β1 signaling in the TME of the KO mice as measured by SMAD3 phosphorylation (pSMAD3) (Fig. 1D, 1E). The decreased pSMAD3 in the Plt-gp96 KO mice was seen in both CD45+ immune and CD45- tumor cells (Fig. 1F, 1G). Flow cytometric analysis of the TIL populations validated the consequences of enhanced TGF-β1 signaling as the Plt-gp96 KO mice had increased frequency of tumor infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with a corresponding decrease in the percentage of CD11b+ myeloid cells (Fig. 1H-1J; Supplemental Fig. 3A). No differences in percentage of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells between WT and KO mice were observed (Supplemental Fig. 3B). The decrease in CD11b+ myeloid cell frequency in the Plt-gp96 KO was largely seen in the F4/80+ macrophage population, whereas the Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes and Ly6G+ neutrophils were comparable between groups (Supplemental Fig. 3C-E). Taken together these data argue that platelets promote tumor growth by enhancing TGF-β1 signaling in both immune and non-immune cells, thereby rewiring TME to form a hostile immunosuppressive environment.

Increased tumor-specific T cell function is associated with dysfunctional platelets

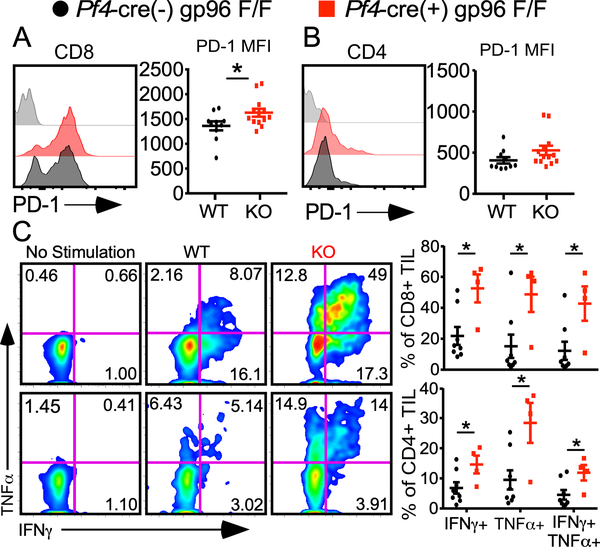

Next, we focused on understanding the role of platelets in altering phenotypic and functional status of T cells in the TME, an important question that has not been answered to our knowledge. Day 15 TIL analysis demonstrated a significant increase in PD-1 expression on CD8+ T cells in the Plt-gp96 KO mice (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, this phenomenon was restricted to the CD8+ but not CD4+ population (Fig. 2B). The expression of PD-1 in this case does not indicate functional exhaustion but more likely activation as both CD4+ and CD8+ TILs from Plt-gp96 KO mice produced significantly more IFN-γ and TNF-α compared to these from WT littermates (Fig. 2C). The increased T cell effector function was restricted to cells in TME as we saw no differences in cytokine production in T cells isolated from the tumor draining lymph nodes (Supplemental Fig. 3F). These data confirm that platelet-mediated influence on the immune signature of tumors in situ bears impactful functional consequences.

FIGURE 2.

Increased tumor-specific T cell function is associated with dysfunctional platelets. TIL analysis from day 15 MC-38 tumors. (A) PD-1 expression on CD8+ tumor cells gated on live CD45+ cells. (B) PD-1 expression on CD4+ tumor cells gated on live CD45+ cells. (C) IFN-γ and TNF-α production from tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells following stimulation with PMA and Ionomycin for 4 hours. (A-B) Grey histogram represents Fluorescence Minus One Control. n = 10–13 per group, representative data from 2 independent experiments. (C) n = 4–8 per group, representative data from 2 independent experiments. (A-C) students t test, * p < 0.05, data presented as mean +/− SEM.

Platelet activation not number influences tumor growth in a CD8+ T cell-dependent manner

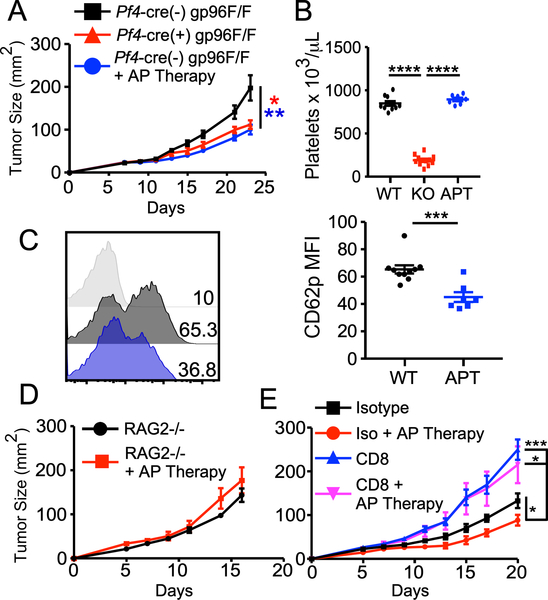

Given the Plt-gp96 KO mice suffer from thrombocytopenia as well as severe platelet dysfunction, we next asked whether improved tumor control in our model was a consequence of platelet number or function (1, 2). To test this, we compared MC-38 tumor growth in WT, Plt-gp96 KO as well as WT mice treated prophylactically with anti-platelet (AP) Therapy consisting of readily available AP agents aspirin and clopidogrel. Aspirin was delivered continuously at 150mg/L in the drinking water while clopidogrel was given as an oral gavage at 30mg/kg body weight every other day. We found that Plt-gp96 KO and AP Therapy treated WT mice had near identical tumor growth rate which was significantly diminished when compared to WT controls (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, AP Therapy had no effect on platelet count (Fig. 3B) while still significantly inhibiting platelet activation as measured by CD62p expression on isolated platelets (Fig. 3C). These findings argue that the functional capacity of platelets is of greater importance on tumor growth than the number of circulating platelets.

FIGURE 3.

Platelet function, not number, influences tumor growth in a CD8+ T cell dependent manner. (A) Tumor growth in WT, Plt-gp96 KO, or WT mice treated prophylactically and continuously with AP Therapy (AT; see methods) challenged with 1 × 106 MC-38 cells. (B) Circulating platelet count of day 14 tumor bearing mice (APT = AP Therapy). (C) CD62p expression on purified platelets from peripheral blood of day 14 tumor bearing mice. (D) MC-38 tumor growth in Rag2−/− mice with or without prophylactic and continuous AP Therapy. (E) MC-38 tumor growth in mice treated with or without AP Therapy, and with or without CD8 depleting antibody. Antibody injection was 200 μg per mouse on day −1, followed by 100 μg every 3 days thereafter for duration of the experiment. (A-E) Representative data from 2–3 independent experiments, all data are presented as mean +/− SEM. (A) N=10–12 mice per group, Two-way repeated measures ANOVA. (B) N=7–12 per group, one-way repeated measure ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. (C) N=7–10 per group, student’s t test. (D) N=5 per group, two-way repeated measures ANOVA. (E) N=6–8 per group, two-way repeated measures ANOVA. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

We next sought to determine whether platelet function was promoting tumor growth via a cancer cell intrinsic or extrinsic mechanism. To test this, we prophylactically treated immune-deficient mice with AP Therapy and then challenged them with MC-38 tumors. The protective effect of AP Therapy was completely lost in Rag2−/− mice indicating that platelet activation promotes tumor growth via suppression of the adaptive immune response (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, antibody-mediated depletion of CD8+ T cells also abrogated the AP Therapy effect with tumor growth rates similar to that seen in the Rag2−/− mice (Fig. 3E). Taken together, these findings strongly support a model in which platelet activation supplements primary tumor growth by increasing an immunosuppressive TME that impedes CD8+ T cell function.

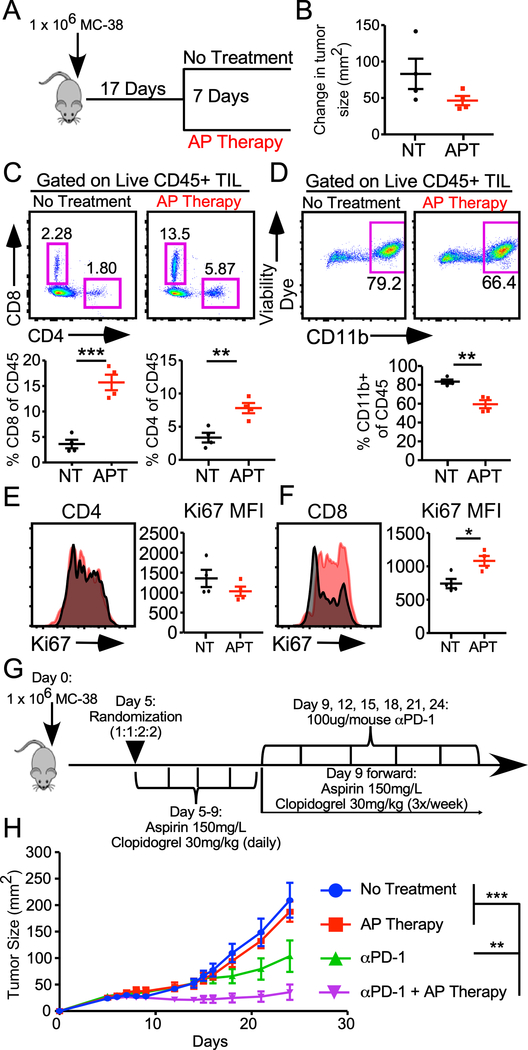

AP Therapy alters the immune landscape of established tumors and synergizes with PD-1 blockade

To assess the clinical relevance of targeted platelet inhibition as a therapeutic strategy, WT mice were challenged with MC-38 and tumors were grown until approximately 50 mm2 (17 days), at which point mice were sorted into either AP Therapy or no treatment group for one week (Fig. 4A). Although the AP Therapy group showed a slight decrase in the change in tumor size over the course of treatment, the difference between cohorts was not significant (Fig. 4B). TIL analysis showed that AP Therapy treatment mimicked our genetic model with increased frequency of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and decreased percentage of CD11b+ myeloid cells compared to non-treated controls (Fig 4C, 4D). AP Therapy resulted in increased proliferation of CD8+, but not CD4+, T cells in the tumor (Fig 4E, 4F). As aspirin has several anti-inflammatory effects that are not platelet-specific, we next sought to validate the changes in the TME we observed were mediated by platelets. A similar experiment was designed where tumors were allowed to grow until approximated 50 mm2 (Day 12) and mice were then given daily injections of rabbit anti-mouse thrombocyte sera or normal rabbit serum control over the course of 4 days (Supplemental Fig. 4A). Circulating platelet counts were dramatically reduced 24 hours post injection (Supplemental Fig. 4B). Furhtermore, we saw a similar same phenotype as the AP Therapy treatment group where mice had increased frequency of CD8+ T cells in the tumor combined with a subsequent decrease in CD11b+ myeloid cells (Supplemental Fig 4C-E). These data unequivocally support a model where platelets suppress antitumor immunity by altering the frequency of effector cells in the TME. Furthermore, these findings also suggest that the platelet effect on the TME is continuous, insofar as this phenomenon is reversible.

FIGURE 4.

AP Therapy alters the immune landscape of established tumors and synergizes with PD-1 blockade. (A) Experimental schematic for data depicted in B-F. (B) Change in tumor size (mm2) over the 7-day course of treatment (NT = No Treatment, APT = AP Therapy). (C) Frequency of tumor infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells gated on live CD45+ cells. (D) Frequency of tumor infiltrating CD11b+ myeloid cells gated on live CD45+ cells. (E) Expression of Ki67 on tumor infiltrating CD4+ T cells gated on live CD45+ cells. (F) Expression of Ki67 on tumor infiltrating CD8+ T cells gated on live CD45+ cells. (G) experimental schematic for data presented in (H). Tumor growth curves of mice treated with or without AP Therapy in the presence or absence of anti-PD-1 Ab. (A-H) All data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments, data presented as mean +/− SEM. (B-F) N=4 per group, student’s t test. (H) N=4–10 per group, two-way repeated measures ANOVA. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Given the increase in CD8+ T cell infiltration and proliferation, we reasoned that pretreating mice with AP Therapy prior to starting an anti-PD-1 regimen would enhance the response. We challenged WT mice with MC-38 and randomized them into one of four treatment groups: 1) no treatment, 2) AP Therapy, 3) anti PD-1 blockade, and 4) AP Therapy + anti PD-1 as soon as tumors became palpable (5 days post injection) (Fig. 4G). We altered the AP Therapy dosing schedule to daily gavages of clopidogrel from days 5 to 9 in order to maximize the amount of platelet inhibition and subsequent increase in CD8+ T cell infiltration into the TME. Once the PD-1 treatment was started we returned to the normal schedule of every other day. Mice that received the combination AP Therapy and PD-1 blockade demonstrated enhanced tumor control compared to the single arm groups or the no treatment group (Fig. 4H). Retrospective analysis of 3 independent experiments found that 1½4 (45.8%) of mice receiving the combination of AP Therapy and PD-1 blockade, irrespective of dose or timing schedule, displayed complete tumor irradication following PD-1 administration compared to 5/24 (20.8%) mice in single arm PD-1 group (data not shown). Taken together, our data show that platelet activation plays a continuous role in shaping the immunosuppressive TME and that a targeted intervention enhances response to PD-1 blockade.

As a non-selective cycloxigenase inhibitor, aspirin has a multitude of effects unrelated to platelets that could potentially confound the interpretation of the data presented here. For example, a recent work from Zaleney and colleagues demonstrated improved tumor control by combining aspirin with PD-1 blockade, a phenomenon they deftly show is mediated via tumor cell production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (17). PGE2 has been shown to promote tumor growth via immune suppression by altering the function of tumor-associated macrophages, dendritic cells, NK cells, as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (18). PGE2 has also been shown to exert pro-aggregatory effects on platelets by amplifying the response to platelet receptor agonists such as thromboxane A2, thrombin and ADP (19). Given our platelet depletion data, in conjunction with our genetic model where the defects are restricted specifically to platelet function and number, it is completely plausible that the pro-tumorgenic effects of PGE2 described by Zaleney et al. is, at least partly, due to sustained platelet activity in the TME.

A growing body of evidence suggests that a key factor in determining successful response to PD-1 blockade is the presence of CD8+ T cells in the tumor (10). We demonstrated that AP Therapy treatment, or antibody mediated platelet depletion, of established tumors significantly enhanced the frequency of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4C, Supplemental Fig 4). In line with this finding, mice receiving the combination treatment had an immediate response to PD-1 blockade whereas the single arm PD-1 group had a delayed treatment effect of approximately 1 week (Fig. 4H). From an experimental standpoint, antibody-induced thrombocytopenia has been the most effective way to study the role of platelets in various disease states. However, as this approach is not feasible clinically, we show here that inhibiting platelet function pharmacologically is just as effective in eliciting cancer control. Given the increased risk of bleeding disorders associated with platelet inhibition, a more thorough analysis of dosing and timing is warranted. Furthermore, exploration of different platelet inhibitors, such as direct thrombin inhibition, as a means to enhance T cell infiltration into tumors is also of extreme intrests.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Platelets alter frequency, phenotype and function of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

Inhibition of platelet activation improves CD8+ T cell-dependent tumor control

Pretreatment with anti-platelet therapy enhances responsiveness to PD-1 blockade

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grants by the NIH: R01CA188419, P01-CA186866 (ZL) and F31CA217010 (BPR). The work presented here was also supported in part by the Translational Science Laboratory, Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina P30 CA138313 (CDT) as well as the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) through Grant Numbers TL1 TR001451 (BPR) and UL1 TR001450 (BPR)

Abbreviations:

- WT

Wild Type

- Plt-gp96 KO

Pf4-cre Hsp90b1Flox/Flox

- AP Therapy

anti-platelet therapy

- PD-1

programmed death receptor 1

- PD-L1

programmed death ligand 1

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

References

- 1.Rachidi S, Metelli A, Riesenberg B, Wu BX, Nelson MH, Wallace C, Paulos CM, Rubinstein MP, Garrett-Mayer E, Hennig M, Bearden DW, Yang Y, Liu B, and Li Z.. 2017. Platelets subvert T cell immunity against cancer via GARP-TGFbeta axis. Sci Immunol 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staron M, Wu S, Hong F, Stojanovic A, Du X, Bona R, Liu B, and Li Z.. 2011. Heat-shock protein gp96/grp94 is an essential chaperone for the platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex. Blood 117: 7136–7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siess W. 1989. Molecular mechanisms of platelet activation. Physiol Rev 69: 58–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wherry EJ 2011. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol 12: 492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, Tatiparti K, Bhise K, Kashaw SK, and Iyer AK. 2017. PD-1 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Signaling Inhibition for Cancer Immunotherapy: Mechanism, Combinations, and Clinical Outcome. Front Pharmacol 8: 561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson CB, and Win SY. 2018. Combination therapy with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: An overview of ongoing clinical trials. Oncoimmunology 7: e1408744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephen TL, Rutkowski MR, Allegrezza MJ, Perales-Puchalt A, Tesone AJ, Svoronos N, Nguyen JM, Sarmin F, Borowsky ME, Tchou J, and Conejo-Garcia JR. 2014. Transforming growth factor beta-mediated suppression of antitumor T cells requires FoxP1 transcription factor expression. Immunity 41: 427–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mariathasan S, Turley SJ, Nickles D, Castiglioni A, Yuen K, Wang Y, Kadel EE III, Koeppen H, Astarita JL, Cubas R, Jhunjhunwala S, Banchereau R, Yang Y, Guan Y, Chalouni C, Ziai J, Senbabaoglu Y, Santoro S, Sheinson D, Hung J, Giltnane JM, Pierce AA, Mesh K, Lianoglou S, Riegler J, Carano RAD, Eriksson P, Hoglund M, Somarriba L, Halligan DL, van der Heijden MS, Loriot Y, Rosenberg JE, Fong L, Mellman I, Chen DS, Green M, Derleth C, Fine GD, Hegde PS, Bourgon R, and Powles T.. 2018. TGFbeta attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 554: 544–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peranzoni E, Lemoine J, Vimeux L, Feuillet V, Barrin S, Kantari-Mimoun C, Bercovici N, Guerin M, Biton J, Ouakrim H, Regnier F, Lupo A, Alifano M, Damotte D, and Donnadieu E.. 2018. Macrophages impede CD8 T cells from reaching tumor cells and limit the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115: E4041–E4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ott PA, Hodi FS, Kaufman HL, Wigginton JM, and Wolchok JD. 2017. Combination immunotherapy: a road map. J Immunother Cancer 5: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yadav M, Jhunjhunwala S, Phung QT, Lupardus P, Tanguay J, Bumbaca S, Franci C, Cheung TK, Fritsche J, Weinschenk T, Modrusan Z, Mellman I, Lill JR, and Delamarre L.. 2014. Predicting immunogenic tumour mutations by combining mass spectrometry and exome sequencing. Nature 515: 572–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juneja VR, McGuire KA, Manguso RT, LaFleur MW, Collins N, Haining WN, Freeman GJ, and Sharpe AH. 2017. PD-L1 on tumor cells is sufficient for immune evasion in immunogenic tumors and inhibits CD8 T cell cytotoxicity. J Exp Med 214: 895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Georgoudaki AM, Prokopec KE, Boura VF, Hellqvist E, Sohn S, Ostling J, Dahan R, Harris RA, Rantalainen M, Klevebring D, Sund M, Brage SE, Fuxe J, Rolny C, Li F, Ravetch JV, and Karlsson MC. 2016. Reprogramming Tumor-Associated Macrophages by Antibody Targeting Inhibits Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cell Rep 15: 2000–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beury DW, Carter KA, Nelson C, Sinha P, Hanson E, Nyandjo M, Fitzgerald PJ, Majeed A, Wali N, and Ostrand-Rosenberg S.. 2016. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Survival and Function Are Regulated by the Transcription Factor Nrf2. J Immunol 196: 3470–3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Wu BX, Metelli A, Thaxton JE, Hong F, Rachidi S, Ansa-Addo E, Sun S, Vasu C, Yang Y, Liu B, and Li Z.. 2015. GP96 is a GARP chaperone and controls regulatory T cell functions. J Clin Invest 125: 859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermeersch E, Denorme F, Maes W, De Meyer SF, Vanhoorelbeke K, Edwards J, Shevach EM, Unutmaz D, Fujii H, Deckmyn H, and Tersteeg C.. 2017. The role of platelet and endothelial GARP in thrombosis and hemostasis. PLoS One 12: e0173329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zelenay S, van der Veen AG, Bottcher JP, Snelgrove KJ, Rogers N, Acton SE, Chakravarty P, Girotti MR, Marais R, Quezada SA, Sahai E, and Reis e Sousa C.. 2015. Cyclooxygenase-Dependent Tumor Growth through Evasion of Immunity. Cell 162: 1257–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain M, Javeed A, Ashraf M, Al-Zaubai N, Stewart A, and Mukhtar MM. 2012. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Pharmacol Res 66: 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vezza R, Roberti R, Nenci GG, and Gresele P.. 1993. Prostaglandin E2 potentiates platelet aggregation by priming protein kinase C. Blood 82: 2704–2713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.