Abstract

Barrier tissues are primary targets of environmental stressors and home to the largest number of antigen-experienced lymphocytes in the body, including commensal-specific T cells. Here, we show that skin-resident commensal-specific T cells harbor a paradoxical program characterized by a type-17 program associated with a poised type-2 state. Thus, in the context of injury and exposure to inflammatory mediators such as IL-18, these cells rapidly release type-2 cytokines, thereby acquiring contextual functions. Notably, such acquisition of a type-2 effector program promotes tissue repair. Aberrant type-2 responses can also be unleashed in the context of local defects in immunoregulation. Thus, commensal-specific T cells co-opt tissue residency and cell-intrinsic flexibility as a means to promote both local immunity and tissue adaptation to injury.

One Sentence Summary:

Local alarmins license type-2 immunity from tissue-resident commensal-specific type-17 T cells.

Barrier tissues are constitutive targets of environmental stressors as well as primary sites of exposure to symbiotic and pathogenic microbes. As such, under homeostasis, barrier tissues are home to vast numbers of antigen-experienced lymphocytes. The numerous and diverse microbes that colonize these tissues, referred to as the microbiota, play a fundamental role in the induction and quality of these local immune responses, including those that are directed at the microbiota itself (1–4). Indeed, far from being ignored, microbes at all barrier surfaces are actively recognized by the immune system. Encounter with non-invasive symbionts can lead to the induction of cognate T cell responses (1–4). This tonic recognition promotes a highly physiological form of adaptive immunity that can control distinct aspects of tissue function including antimicrobial defense and tissue repair (5, 6). Because of the extraordinary number of antigens expressed by the microbiota, a significant fraction of barrier tissue-resident T cells are expected to be commensal-specific, accumulating over time in response to successive exposure to new commensals. This understanding of host–microbiota interactions has important implications for our understanding of host immunity and pathologies. Since barrier tissues are defined by the constitutive coexistence of commensals (and associated antigens) and commensal-reactive lymphocytes, understanding tissue homeostasis, response to injury, and tissue-specific pathologies must occur in the context of this fundamental dialogue.

The skin serves as a primary interface with the environment and is consequently a constitutive target of environmental stressors mediated by physical damage, invasive pathogens, impaired immune regulation or the nutritional state of the host. Tissue protection from these challenges relies on rapid and coordinated local responses tailored to both the microenvironment and the nature of the instigating injury. Recently, the discovery that cells such as innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) can rapidly respond to mediators released during tissue damage has provided a framework to begin to understand this phenomenon. Whether tissue-resident T cells, particularly those specific to commensals, can also act as tissue sentinels allowing rapid adaptation to defined injury remains unknown. Here, we explore the unique features of commensal-specific T cells and how their distinct wiring might promote physiological or pathological tissue adaptation.

RESULTS

Acute injury licenses type-2 cytokine production from commensal-specific type-17 T cells

The skin is home to a number of resident lymphocytes, some of which recognize the microbiota (4, 6–8). We first assessed whether commensal-specific T cells could develop as non-recirculating tissue-resident memory cells (TRM), a subset of memory T cells previously shown to accumulate in tissues upon pathogen encounter and promote local immunity (9). Staphylococcus epidermidis colonization of the skin promotes the non-inflammatory accumulation of both CD4+ (Th1 and Th17) and CD8+ T cells (Tc1 and Tc17) (4). A large fraction (> 80%) of these S. epidermidis-specific polyclonal CD8+ T cells are non-classically restricted (6). S. epidermidis-specific CD8+ T cells can be tracked via the utilization of a peptide:MHC tetramer (f-MIIINA:H2-M3)(6) and newly generated T cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic mice (BowieTg). Both tools recapitulate the S. epidermidis-specific polyclonal CD8+ T cell response, including cytokine potential, skin-homing, and distribution of the tissue residency markers CD69 and CD103 (9) (Fig. 1, A to C). To assess tissue residency, we generated S. epidermidis-colonized parabiotic mice, which establish chimerism through joint circulation (10) (fig. S1A). In contrast to lymphoid organs, where cells equilibrated, within the skin, f-MIIINA:H2-M3+ CD8+ T cells were host-derived (97.1% ± 2.4%) and co-expressed CD103 and CD69 (Fig. 1, D and E). Thus, commensal-specific T cells can develop as long-lived tissue-resident memory T cells.

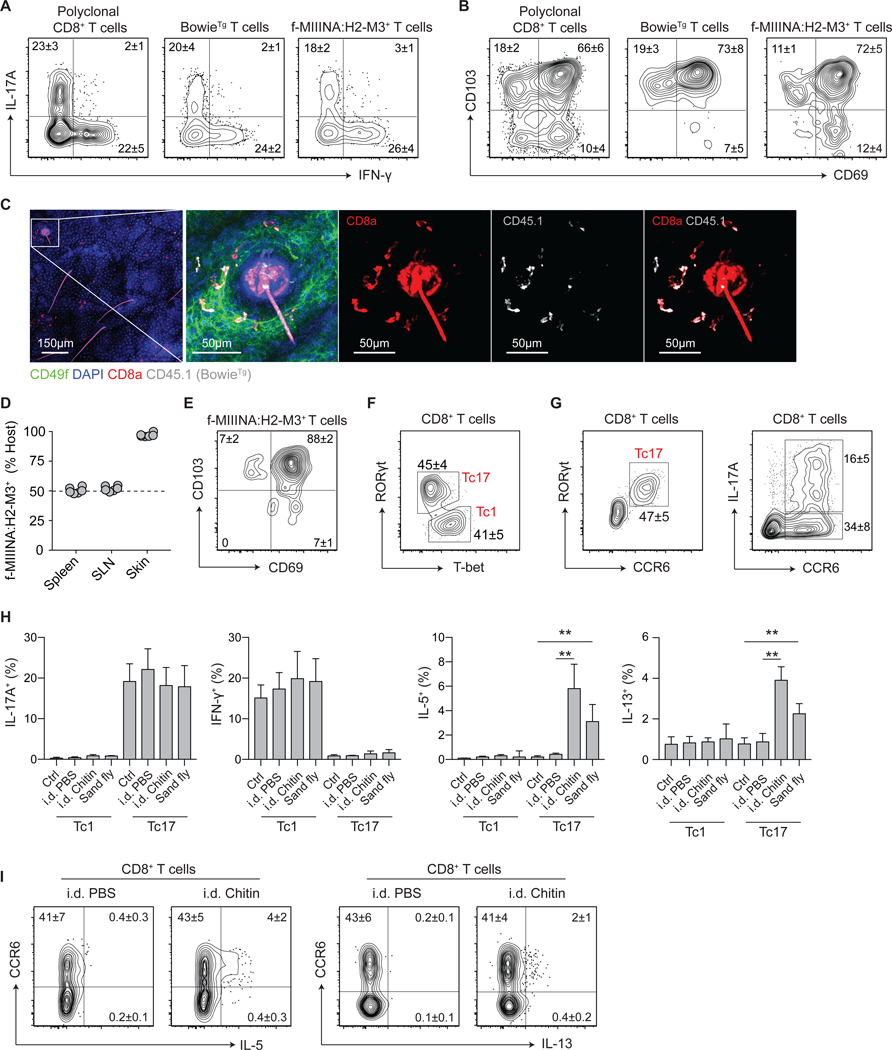

Figure 1: Acute injury licenses type-2 cytokine production from commensal-specific type-17 cells.

(A-C) S. epidermidis-specific T cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic CD8+ T cells (BowieTg) were adoptively transferred to WT mice prior to colonization with S. epidermidis. (A) Representative contour plots of IL-17A and IFN-γ production potential and (B) expression of tissue residency markers CD69 and CD103 by indicated CD8+ T cell populations. (C) Representative confocal imaging volume projected along the z-axis of epidermal skin from S. epidermidis-colonized mice. (D-E) Conjoined pairs of S. epidermidis-colonized CD45.1 and CD45.2 mice were analyzed 90 days after parabiosis surgery for cellular origin and phenotype. (D) Frequency of host-derived f-MIIINA:H2-M3+ CD8+ T cells in indicated tissues; skin-draining lymph nodes (SLN). (E) Representative contour plot of CD69 and CD103 expression by skin f-MIIINA:H2-M3+ CD8+ T cells. (F) Representative contour plot of RORγt and T-bet expression by CD8+ T cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice. (G) Representative contour plots of RORγt, CCR6, and IL-17A expression by CD8+ T cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice. (H-I) S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice were exposed to bites from sand flies (L. longipalpis) or injected intradermally (i.d.) with PBS or chitin. (H) Frequencies of Tc1 and Tc17 cells with cytokine producing potential from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice following skin injury. (I) Representative contour plots of IL-5 and IL-13 production potential by CD8+ T cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice following skin injury. Numbers in representative plots indicate mean ± SD. Bar graphs are represented as mean ± SD. Data represent at least two experiments with 4–6 mice per group. **p < 0.01 as calculated using one-way ANOVA with Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparison test.

Given the fundamental role of the skin as a protective barrier, we sought to determine the impact of environmental stressors on commensal-specific tissue-resident T cells. Following colonization, S. epidermidis-specific polyclonal CD8+ T cells were identified as T-bet+CCR6− Tc1 cells or RORγt+CCR6+ Tc17 cells (of which ~30% have IL-17A production potential) (Fig. 1, F and G). Although the intradermal injection of chitin or sand fly (Lutzomyia longipalpis) bites had no impact on the potential for IL-17A and IFN-γ production by Tc17 and Tc1 cells respectively (Fig. 1H), both stressors revealed a surprising potential for the production of IL-5 and IL-13 from S. epidermidis-elicited Tc17 cells, including f-MIIINA:H2-M3+ CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1, H and I, fig. S1, B and C). Increased type-2 cytokine production post chitin or sand fly challenge was also observed from RORγt-expressing CD4+ T cells (Th17) elicited by S. epidermidis (fig. S1D). Thus, RORγt+ T cells (both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells) elicited by encounter with a commensal may have the unexpected potential to produce type-2 cytokines in response to defined tissue challenges.

Local defects in immunoregulation unleash type-2 immunity from commensal-specific T cells

Flow-cytometric analysis revealed that Tc17 cells co-expressed GATA-3, the lineage-defining transcription factor (LDTF) for both Th2 cells and ILC2 (Fig. 2A). Such a phenotype was also detected among the very few CD8+ T cells present in the skin of naïve mice (fig. S2A) and co-expression of RORγt and GATA-3 by S. epidermidis-specific BowieTg CD8+ T cells was restricted to the skin and not detectable in secondary lymphoid organs, suggesting that GATA-3 expression is imprinted within the tissue microenvironment (fig. S2B). This phenotype was conserved across T cell lineages and distinct microbial exposures. Notably, Th17 cells elicited by skin colonization with S. epidermidis or Candida albicans also expressed GATA-3 (Fig. 2B, fig. S2C). Thus, homeostatic encounter with bacterial or fungal commensal microbes can lead to the development of cells with a paradoxical phenotype characterized by the co-expression of classically antagonistic transcription factors.

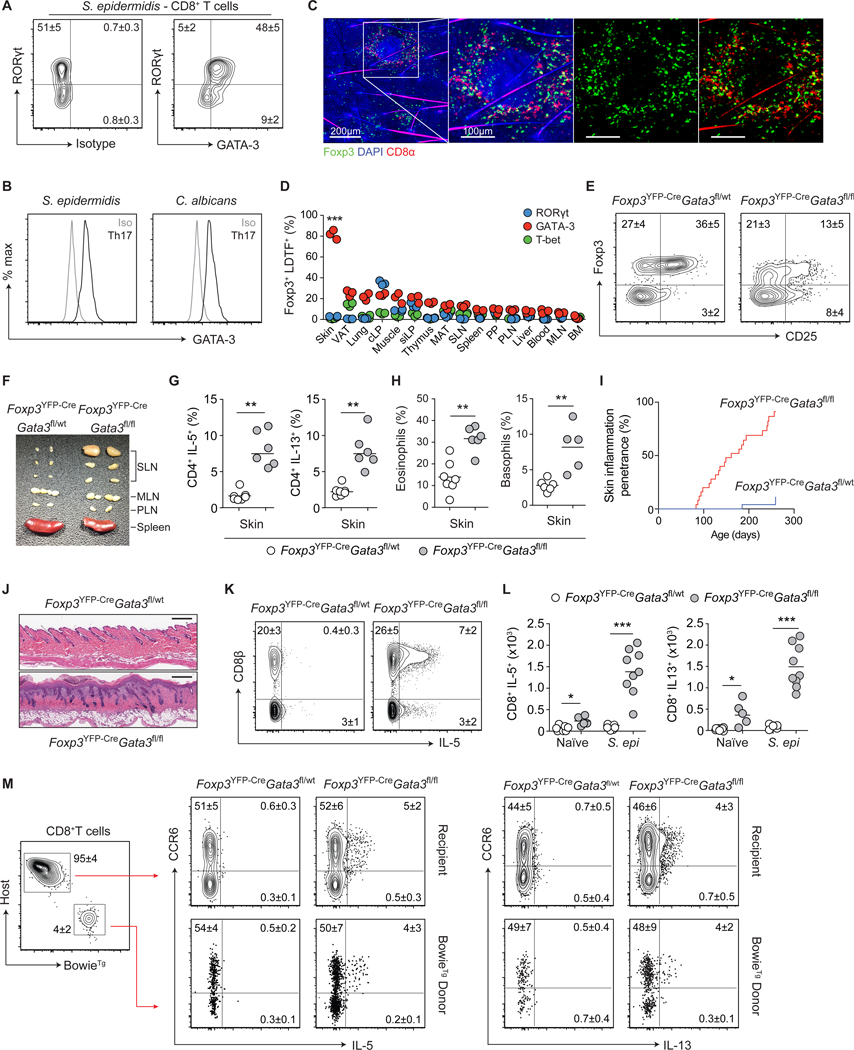

Figure 2: Local defects in immunoregulation unleash type-2 immunity from commensal-specific T cells.

(A) Representative contour plots of RORγt and GATA-3 expression by skin CD8+ T cells from S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice. (B) Representative histogram plots of GATA-3 expression by RORγt+ CD4+ Th17 cells from the skin of commensal-colonized WT mice. (C) Representative confocal imaging volume-projected along the z-axis of epidermal skin from S. epidermidis-colonized Foxp3gfp mice. (D) Frequencies of Foxp3+ Treg cells co-expressing lineage-defining transcription factors (LDTFs) within indicated tissues of naïve WT mice. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT), colonic lamina propria (cLP), small intestinal lamina propria (siLP), mesenteric adipose tissue (MAT), skin-draining lymph nodes (SLN), Peyer’s patch (PP), para-aortic lymph nodes (PLN), mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), and bone marrow (BM). (E) Representative contour plots of Foxp3 and CD25 expression by skin CD4+ T cells from naïve Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/wt and Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice. (F) Representative cutaneous lymphadenopathy in Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl compared to Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/wt control mice. (G) Frequencies of IL-5- and IL-13-producing skin CD4+ T cells from naïve Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/wt and Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice. (H) Frequencies of skin eosinophils and basophils from naïve Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/wt and Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice. (I) Cumulative incidence of skin inflammation among naïve Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/wt and Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice. (J) Representative histological micrograph of skin tissue from naive Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/wt and Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice. Scale bar: 250 μm. (K) Representative contour plots of CD8β expression and IL-5 production potential by TCRβ+ T cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/wt and Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice. (L) Total numbers of IL-5 and IL-13-producing CD8+ T cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/wt and Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice. (M) Representative contour plots of IL-5 and IL-13 production by CD8+ T cells in Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/wt and Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice adoptively transferred with BowieTg T cells prior to colonization with S. epidermidis. Numbers in representative plots indicate mean ± SD. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Data represent at least two experiments with 3–7 mice per group. Cumulative skin inflammation data (I) represent 25 mice per genotype. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 as calculated using Student’s t-test (G, H) or one-way ANOVA with Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparison test (D, L).

The skin is highly enriched in Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells (5), and confocal imaging revealed co-localization of S. epidermidis-induced CD8+ T cells and Foxp3+ Treg cells (Fig. 2C). As such, we assessed the possibility that skin Foxp3+ Treg cells could limit type-2 cytokine production by commensal-specific type-17 cells. Because complete ablation of Foxp3+ Treg cells results in severe local and systemic inflammatory responses and aberrant accumulation of Tc1 cells within the skin (11) (fig. S2, D and E), we utilized an approach allowing for a tissue-specific defect in immunoregulation. Within the skin, Treg cells express high levels of GATA-3 (but not other LDTFs) (Fig. 2D, fig. S2F), a factor that contributes to Treg cell stability and fitness (12–15). In mice in which Treg cells were conditionally deleted of GATA-3 (Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl), Foxp3+ cells were reduced in frequency and exhibited decreased Foxp3 and CD25 expression in the skin, but not in other tissues (Fig. 2E, fig. S2, G and H). Consistent with this observation, by 10 weeks of age, skin-draining lymph nodes, but not other lymphoid structures, were enlarged and the skin compartment (but not other tissues) of these mice were characterized by a selective increase in the number of T cells producing IL-5 and IL-13 (Fig. 2, F and G, fig. S2, I to K). Enhanced type-2 responses were associated with discrete elevated frequencies and absolute numbers of eosinophils and basophils in the skin of Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl compared to control mice (Fig. 2H, fig. S2L). Of note, and in agreement with a skin-specific defect, naïve Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice, with an endogenous skin microbiota but not S. epidermidis, spontaneously developed severe skin inflammation (but not systemic inflammation) with ~70% penetrance by 8 months of age (Fig. 2, I and J). To assess the possibility that T cells producing type-2 cytokines within the skin of these mice are commensal-specific, we colonized young Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl mice (prior to inflammation) and control mice with S. epidermidis and tracked the fate of S. epidermidis-specific T cells. Adoptively transferred BowieTg CD8+ T cells (as well as host polyclonal S. epidermidis-induced CD8+ T cells) expressed IL-5 and IL-13 proteins in the skin of Foxp3YFP-CreGata3fl/fl, but not control mice (Fig. 2, K to M). By contrast, the ability of S. epidermidis-elicited CD8+ T cells to produce IL-17A or IFN-γ was unaffected (fig. S2M). Notably, type-2 cytokine production by S. epidermidis-specific polyclonal and adoptively transferred BowieTg CD8+ T cells remained restricted to cells expressing CCR6, demonstrating that, in the context of local immune defects, type-2 cytokines can be unleashed from RORγt-committed T cells (Fig. 2M). Thus, impaired local immunoregulation promotes type-2 cytokine production by commensal-specific type-17 cells, a property that may predispose tissue to inflammation.

S. epidermidis-specific Tc17 cells harbor a poised type-2 transcriptome

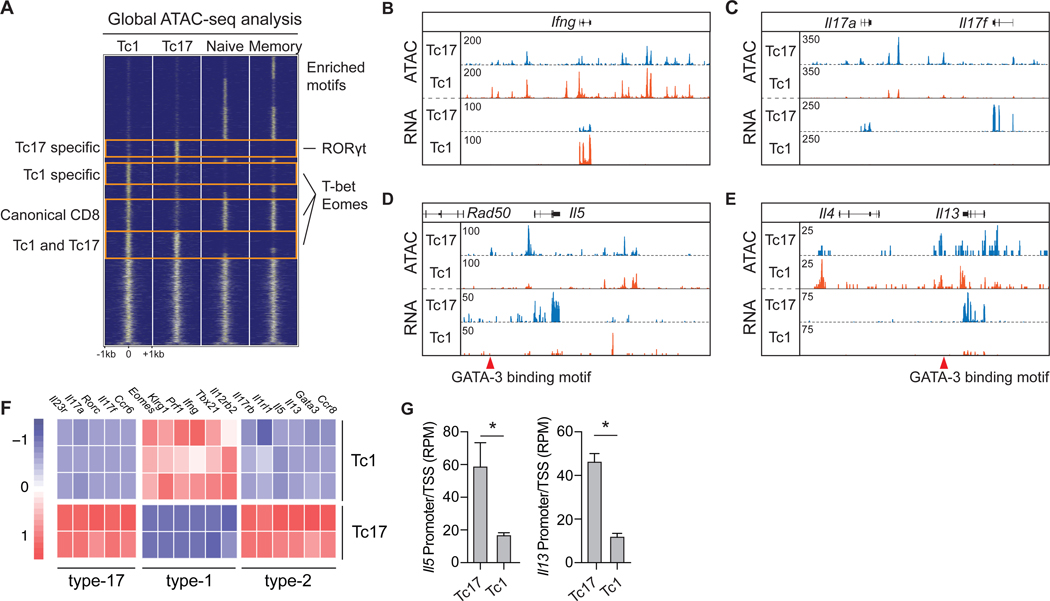

To gain insight into the transcriptional and epigenetic landscape of commensal-specific T cells under homeostatic conditions, we identified global regulatory elements shared between, and unique to, S. epidermidis-specific polyclonal Tc17 (CCR6+) and Tc1 (CCR6−) cells from the skin and naïve and memory CD8+ T cells from lymphoid tissue (16). Regulatory elements unique to skin Tc17 or Tc1 cells were enriched in binding sites for RORγt, and T-bet and Eomes respectively (Fig. 3A), consistent with subset-specific expression of these LDTFs (Fig. 1F). Elevated chromatin accessibility and transcript abundance of the signature cytokines Ifng, Il17a, and Il17f also confirmed the clear distinction between Tc1 and Tc17 cell subsets (Fig. 3, B and C, fig. S3, A and B). Among regulatory elements unique to Tc17 cells, we identified previously described GATA-3-binding sites within Il13 and the Rad50/Th2 locus control region (17) (Fig. 3, D and E). Consequently, Tc17 cells demonstrated elevated chromatin accessibility at type-2 immune gene loci encoding Il5 and Il13 and expressed elevated levels of Il5 and Il13 mRNA transcripts compared to Tc1 cells (Fig. 3, D to G, fig. S3C). Furthermore, Tc17 cells expressed a broad type-2 transcriptome, including a LDTF (Gata3) and cytokine and chemokine receptors (Ccr8, Il1rl1, and Il17rb), but neither Il4 nor Il10 mRNA, as previously described for tissue-derived Th2 cells (18) (Fig. 3F, fig. S3D). The type-2 associated cytokine amphiregulin (Areg) was detectable in both cell subsets, albeit at higher abundance in Tc17 cells (fig. S3D). As such, commensal-specific Tc17 cells express a broad type-2 transcriptome under homeostatic conditions.

Figure 3: S. epidermidis-specific Tc17 cells express a broad type-2 signature.

(A-G) Tc17 (CD8+CCR6+) and Tc1(CD8+CCR6−) cells were isolated by FACS from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice for transcriptomic and epigenetic analysis by RNA-seq and ATAC-seq. ATAC-seq signals from canonical naïve and memory CD8+ T cells were from lymphoid tissue. (A) Global comparison of ATAC-seq signals in S. epidermidis-induced Tc17 and Tc1 and canonical naïve and memory CD8+ T cells. Representative transcription factor binding motifs enriched in indicated groups are listed on the right. (B-E) Genomic tracks of ATAC-seq and RNA-seq signal profiles in Tc17 and Tc1 cells across signature cytokine genes. Genomic location of Tc17-specific regulatory elements with GATA-3 binding motifs are denoted by red triangles. (F) Heatmap of lineage-specific signature genes expressed by Tc17 and Tc1 populations. (G) Chromatin accessibility at transcription start site (promoter ± 500 bp) of Il5 and Il13 in Tc17 and Tc1 cells. Bar graphs are represented as mean ± SD. Sequencing data represent 2–3 independent biological replicates. *p < 0.05 as calculated using Student’s t-test.

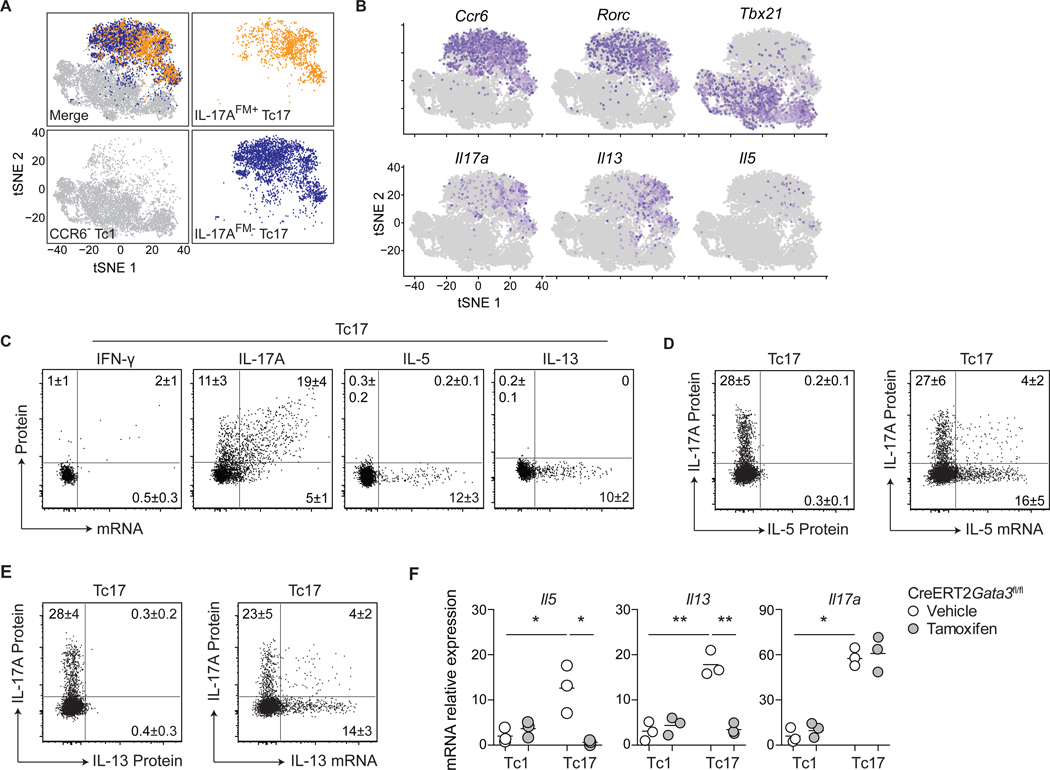

Of S. epidermidis-induced Tc17 cells, ~30% displayed the potential for IL-17A production (Fig. 1G), supporting the idea of possible phenotypic heterogeneity. However, using cells from IL-17A-fate-mapping mice (IL-17AFM - Il17aCreR26ReYFP) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), tSNE projection of Tc1, IL-17AFM+ Tc17 and IL-17AFM− Tc17 cells demonstrated considerable transcriptional overlap between IL-17AFM+ and IL-17AFM− Tc17 cell fractions, with type-2 cytokine mRNA expressing cells present in both fractions (Fig. 4, A and B, fig. S4A). Thus, commensal-specific Tc17 cells, including those already committed to IL-17A-production, can be superimposed with the expression of a type-2 transcriptome. Furthermore, in situ hybridization for mRNA detection by flow cytometry revealed that Il5 and Il13 transcripts, but not protein, were expressed selectively by Tc17 cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized mice (Fig. 4C, fig. S4B). In line with our scRNA-seq data (Fig. 4B, fig. S4A), Il5+ and Il13+ cells were found within both IL-17A-producing and -non-producing fractions of Tc17 cells (Fig. 4, D and E), suggesting that during homeostasis, commensal-specific Tc17 cells express type-2 cytokine mRNA without subsequent protein translation. The inducible deletion of Gata3 at the peak of the CD8+ T cell response to S. epidermidis revealed that sustained GATA-3 expression by Tc17 cells was required for the constitutive expression of Il5 and Il13, but, as expected, not for Il17a (Fig. 4F). Thus, S. epidermidis-specific Tc17 cells express a poised type-2 transcriptome dependent on continued GATA-3 expression.

Figure 4: S. epidermidis-specific Tc17 cells harbor a poised type-2 transcriptome.

(A-B) Tc1 (CD8+CCR6−), IL-17AFM+ Tc17 (CD8+CCR6+eYFP+) and IL-17AFM− Tc17 (CD8+CCR6+eYFP−) cells were isolated by cell sorting from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized Il17aCreR26ReYFP (IL-17AFM) mice and analyzed by scRNA-seq. (A) t-Distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plots of the scRNA-seq expression highlighting Tc1 (gray), IL-17AFM+ Tc17 (orange), and IL-17AFM− Tc17 (blue) populations. (B) Expression of LDTFs and cytokine genes projected onto a tSNE plot. (C) Representative dot plots of cytokine protein production potential and mRNA expression by Tc17 cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice. (D-E) Representative dot plots of IL-17A and IL-5 or IL-13 production potential and Il5 or Il13 mRNA expression by Tc17 cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice. (F) S. epidermidis-colonized CreERT2Gata3fl/fl mice received tamoxifen or vehicle control prior to cell sorting of skin Tc1 and Tc17 cells. Gene expression, in the indicated populations, was assessed by qRT-PCR. Numbers in representative plots indicate mean ± SD. Flow cytometric data represent at least two experiments with 4–6 mice per group. qRT-PCR data represent three biological replicates of eight pooled mice per group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 as calculated using one-way ANOVA with Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparison test.

Accordingly, type-2 cytokine competency (mRNA expression) and licensing (stimuli-induced protein production) are temporally decoupled in S. epidermidis-elicited Tc17 cells, a process likely involving the post-transcriptional regulation of cytokine mRNA stability and protein translation. Under inflammatory conditions, previous work revealed that distinct stimuli can govern competency and licensing of type-2 immunity within injured tissues, ensuring tissue-restricted effector function during pathogen infection (19). Recent findings also suggest that IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells is actively regulated at the level of translation, thereby preventing chronic immune activation (20–22).

Alarmins license type-2 cytokine production by commensal-specific Tc17 cells

Our work proposes that such a phenomenon may also apply to commensal-specific T cells generated under homeostatic conditions. To identify the factors capable of licensing poised type-2 immunity from commensal-specific T cells, we employed an ex vivo screening approach, stimulating Tc17 and Tc1 cells with cytokines and alarmins previously shown to be associated with tissue damage. Cytokine stimulation alone did not promote type-2 cytokine production by skin T cells, demonstrating that these cells cannot be licensed in a TCR-independent manner (fig. S5A). As commensal microbes persist within the skin, this result is consistent with the fact that exposure to alarmins is expected to occur in the context of antigen exposure. However, in line with the role of IL-1 within the skin (4), IL-1α significantly increased the ex vivo production of IL-17A from Tc17 cells in the context of TCR stimulation (Fig. 5A). As previously reported, IL-18 and IL-33 promote IFN-γ production by Tc1 cells (23, 24) (Fig. 5B). Notably, several alarmins promoted the production of IL-5 (IL-18, IL-25, and IL-33) or IL-13 (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33)(Fig. 5, C and D). IL-25 potently promoted production of IL-5, but not IL-13 (Fig. 5, C and D), supporting the idea that distinct classes of injury may differentially impact commensal-specific T cell responses. Strikingly, IL-18, a cytokine widely linked to the initiation of type-1 responses, was particularly potent at eliciting the release of both IL-5 and IL-13 from Tc17 cells ex vivo (Fig. 5, C and D). IL-18 also promoted IL-17A production by Tc17 cells, further supporting the idea that this alarmin can superimpose type-2 responses upon a pre-committed type-17 program (Fig. 5A). Under these conditions, IL-4 and IL-10 were undetectable (fig. S5B), but both Tc1 and Tc17 cells produced amphiregulin upon TCR stimulation, a response that was also enhanced by IL-18 (fig. S5C). Type-2 responses to IL-18 were not restricted to CD8+ T cells nor to S. epidermidis-elicited cells. Indeed, skin CD4+ T cells induced by S. epidermidis or C. albicans colonization (including Th17 cells) also produced higher levels of IL-5 and IL-13 upon IL-18 and TCR stimulation in vitro (fig. S5, D to F). Thus, such poised type-2 potential may be the norm for type-17 commensal-specific T cells raised under homeostatic conditions. In this context, local inflammatory factors including IL-1, IL-18, IL-25, and IL-33 can superimpose a type-2 effector program.

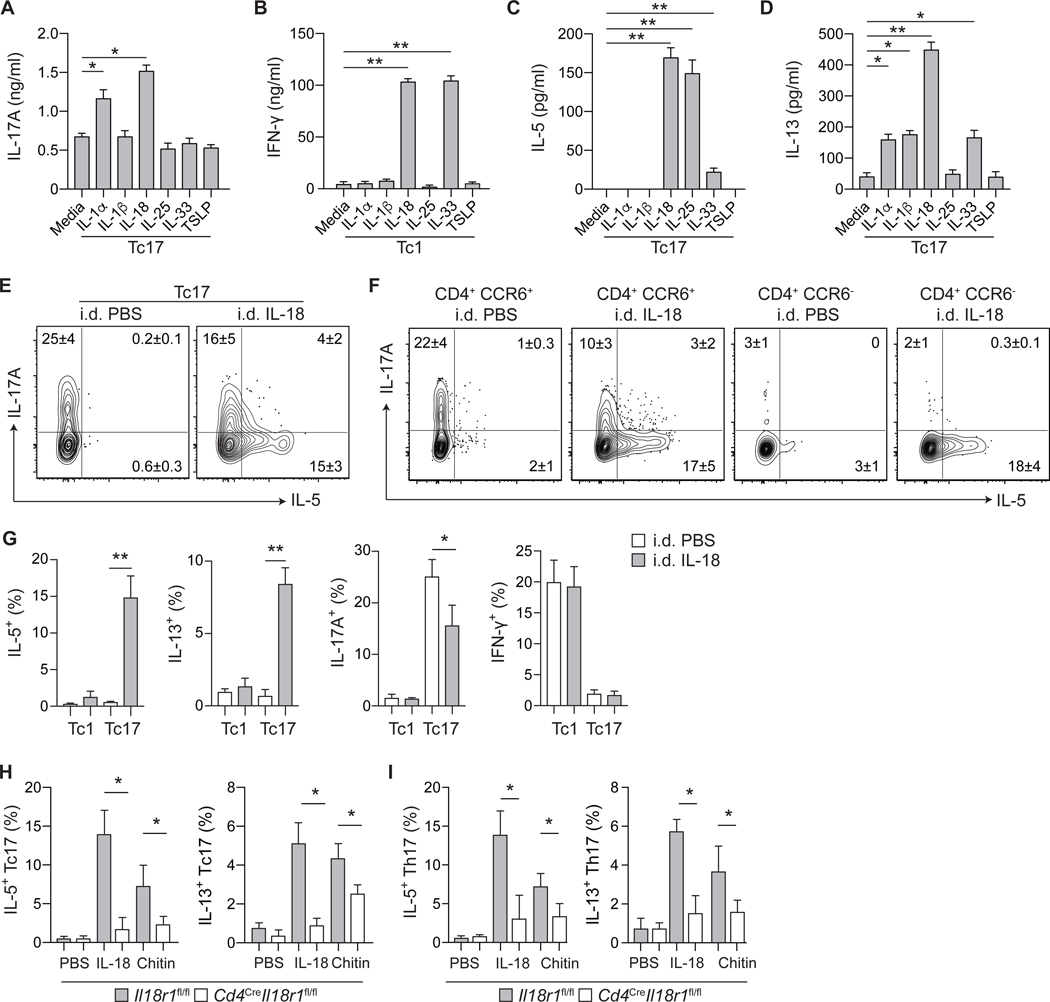

Figure 5: Tissue alarmins license type-2 cytokine production from commensal-specific T cells.

(A-D) Tc17 (CD8+CCR6+) and Tc1 (CD8+CCR6−) cells were isolated from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice and cultured in vitro with agonistic anti-CD3ε mAb and indicated cytokines. Cell culture supernatants were assayed for cytokine production after 24 hours of culture. (E) Representative contour plots of IL-5 and IL-17A production potential by S. epidermidis-induced Tc17 cells, following i.d. injection with PBS or IL-18. (F) Representative contour plots of IL-5 and IL-17A production potential by skin CD4+Foxp3− T cells from S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice, following i.d. injection with PBS or IL-18. (G) Frequencies of Tc17 and Tc1 cells with indicated cytokine production potential from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice following i.d. injection of PBS or IL-18. (H-I) Frequencies of (H) Tc17 and (I) Th17 cells with indicated cytokine production potential from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized Cd4CreIl18r1fl/fl and control mice following i.d. injection with PBS, IL-18 or chitin. Numbers in representative plots indicate mean ± SD. Bar graphs are represented as mean ± SD. Data represent at least two experiments with 3–6 mice per group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 as calculated using one-way (A-D, G) or two-way (H, I) ANOVA with Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparison test.

To assess the impact of a single defined alarmin on commensal-specific T cells, we next focused on the impact of IL-18 in vivo. A single injection of IL-18 licensed both IL-5 and IL-13 protein production by S. epidermidis-elicited Tc17 (including f-MIIINA:H2-M3+ cells) and CD4+ T cells (including Th17 cells) (Fig. 5, E to G, fig. S5, G and H). Type-2 cytokine licensing by IL-18 occurred at the expense of IL-17A production, suggesting dynamic regulation of cytokine production by commensal-specific Tc17 and Th17 cells in vivo (Fig. 5, E to G). The ability of Tc17 and Th17 cells to produce type-2 cytokines in response to IL-18 was dependent upon T cell-intrinsic IL-18R1-signaling (Fig. 5, H and I), and was sustained up to 60 days post-colonization (fig. S5I). Of note, following chitin injection, type-2 licensing of Tc17 and Th17 cells was also IL-18R1-signaling dependent (Fig. 5, H and I), supporting the idea that in defined inflammatory settings, IL-18 alone may be sufficient to impose this response.

Commensal-specific T cell plasticity and IL-13 production promote wound repair

The co-production of cytokines associated with distinct T cell subsets can occur during inflammation. For example, IL-17A+IFN-γ+ cells are present during intestinal and CNS inflammation, and IL-17A+IL-4+ cells are found during allergic asthma and helminth infection (25–29). Previous studies also demonstrated plasticity of effector Th17 cells to convert to Th1, follicular helper (TFH), and Treg cell phenotypes in a context-dependent manner (26, 30, 31). Our work supports the idea that such plasticity may be a fundamental feature of tissue-resident commensal-specific T cells. To specifically address this point, we utilized IL-17AFM mice to assess in vivo the heritage of Tc17 cells licensed for type-2 cytokine production. In line with the finding that both IL-17AFM− and IL-17AFM+ Tc17 cells display poised Il5 and Il13 mRNA expression (Fig. 4, B to E), IL-18 triggered type-2 cytokine production from both Tc17 and Th17 cells regardless of whether they had previously expressed IL-17A (IL-17AFM+ and IL-17AFM−) (Fig. 6, A and B). Thus, within commensal-induced Tc17 and Th17 cell populations, plasticity among IL-17AFM+ cells and local licensing of IL-17AFM− cells both contribute to alarmin-mediated induction of type-2 cytokine production.

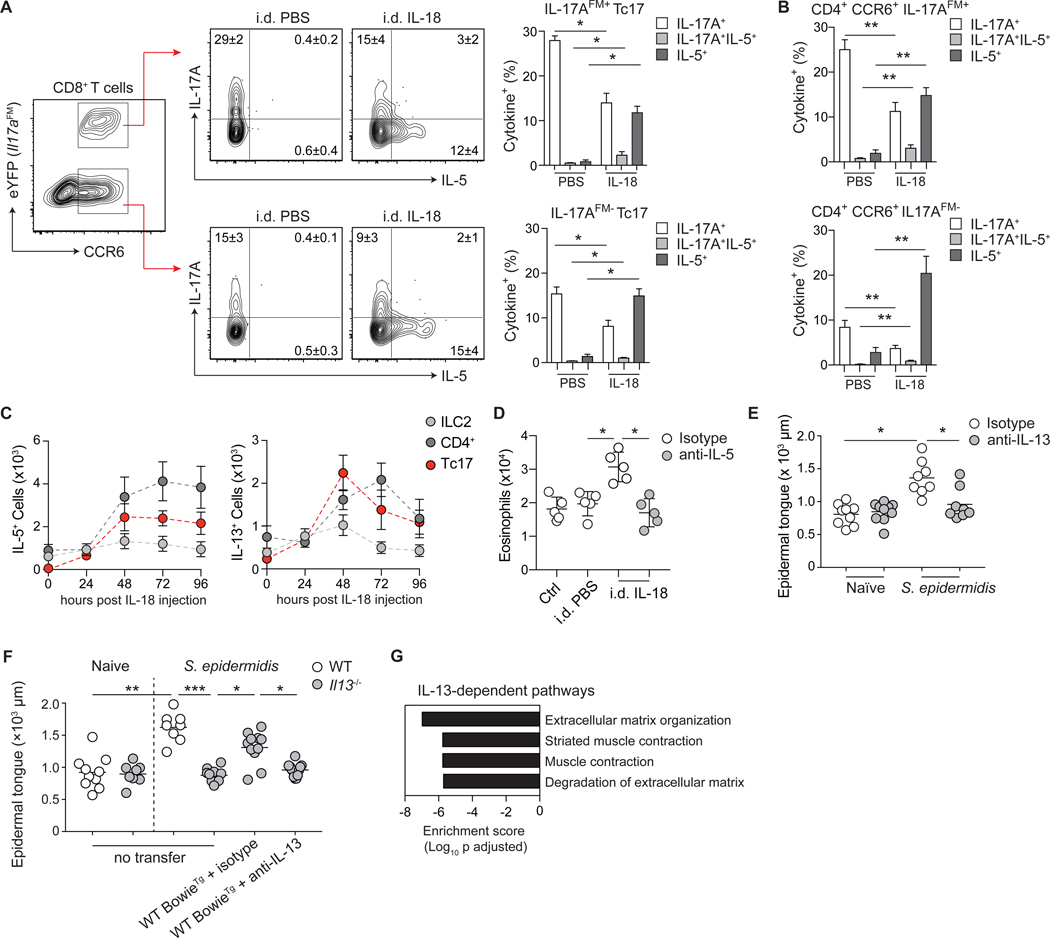

Figure 6: Commensal-specific T cell plasticity and IL-13 production promote wound repair.

(A) Representative contour plots for gating strategy of CCR6 and eYFP expression by CD8+ T cells from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized Il17aCreR26ReYFP (IL-17AFM) mice following i.d. injection of PBS or IL-18. Contour plots represent IL-5 and IL-17A production potential of IL-17AFM+ Tc17 (CD8+CCR6+eYFP+) or IL-17AFM− Tc17 (CD8+CCR6+eYFP−) T cells following i.d. injection of PBS or IL-18. (B) Frequencies of Th17 cells with IL-17A or IL-5 producing potential from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized IL-17AFM mice following i.d. injection of PBS or IL-18. (C) Absolute cell number of IL-5 and IL-13-producing lymphocyte subsets in the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice following i.d. injection of IL-18. Data represented as mean ± SD of five mice per group. (D) Absolute number of eosinophils from the skin of S. epidermidis-colonized WT mice following i.d. injection with PBS or IL-18, and i.p. injection with anti-IL-5 or isotype control. (E-F) Naïve and S. epidermidis-colonized WT and Il13−/− mice, with or without adoptive transfer of BowieTg CD8+ T cells prior to colonization and isotype or anti-IL-13 antibodies at the time of wounding, were subjected to back-skin punch biopsy. Quantification of epithelial tongue length of wound-bed-infiltrating keratinocytes 5 days post wounding. (G) Pathway analysis using differentially expressed genes between d3 isotype and d3 anti-IL-13 wounding groups was performed using Enrichr and graphed based on enrichment score for significant Reactome biological processes. Numbers in representative plots indicate mean ± SD. Bar graphs are represented as mean ± SD. Data represent at least two experiments with 3–7 mice per group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 as calculated using one-way (A, B, D) or two-way (C, E, F) ANOVA with Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparison test.

Although a few reports have suggested that IL-18 can potentially promote type-2 and regulatory responses (32–34), this cytokine is more widely considered to promote type-1 immunity. In support of a major role for IL-18 in the promotion of skin type-2 responses, IL-18 injection promoted type-2 cytokine production not only by T cells, but also as recently described by ILC2 (Fig. 6C) (35). In contrast to transient ILC2 responses, induction of type-2 cytokine expression by T cells was sustained up to 4 days post injection (Fig. 6C). Thus, type-2 cytokine licensing by IL-18 may have a profound effect on skin physiology via the broad impact of a defined alarmin on both tissue-resident commensal-specific T cells, and ILC2 (35). Indeed, IL-18 injection promoted an IL-5-dependent eosinophil accumulation within the skin compartment of S. epidermidis-colonized mice (Fig. 6D, fig. S6A). Thus, tissue-resident commensal-specific type-17 T cells can adapt to defined injury by direct sensing of alarmins and inflammatory mediators.

Because of the known contribution of type-2 immunity and IL-13 in particular to tissue repair, we next utilized a model of skin wounding to assess the potential contribution of commensal-specific type-2 cytokine licensing to this fundamental process. Although IL-13 did not contribute to the healing process in unassociated mice, IL-13 neutralization or genetic Il13-deficiency impaired S. epidermidis-accelerated wound repair (Fig. 6, E and F). Adoptive transfer of WT BowieTg CD8+ T cells rescued this defect in an IL-13-dependent manner (Fig. 6F). In agreement with the role of IL-13 in tissue repair (36), whole-tissue RNA-seq of skin following wounding revealed an IL-13-dependent transcriptional signature dominated by pathways associated with muscle contractility and extracellular matrix re-organization (Fig. 6G, fig. S6B). Notably, in line with the fact that punch biopsies can trigger the release of numerous factors able to license type-17 cells (Fig. 5, C and D), IL-18 was insufficient to promote these responses (fig. S6C). Thus, the poised type-2 immune potential of commensal-specific Tc17 cells allows for local adaptation to injury, thereby promoting tissue repair.

CONCLUSION

Barrier tissues are constitutively exposed to environmental stressors and primary targets of chronic inflammatory disorders. The maintenance of tissue integrity and function represent a complex challenge that requires both resilience and adaptation. Under steady-state conditions, tissue resilience is, in part, mediated by innate and adaptive immunity to the microbiota, which reinforces barrier function and immunity (5). Here, we show that adaptation of tissue to injuries can also be mediated by immunity to the microbiota, a fundamental but poorly understood class of immunity. Notably, we found that homeostatic immunity to bacteria or fungal commensals is characterized by the co-expression of paradoxical programs, allowing commensal-specific T cells, when entering and persisting within tissues, to adopt a type-17 program compatible with tissue homeostasis and immunity while maintaining a type-2-poised state. As such, in the context of injury and consequent exposure to inflammatory mediators and cognate antigens, commensal-specific T cells rapidly release type-2 cytokines, allowing these cells to exert pleiotropic and contextual functions including tissue repair. Thus, we describe a tissue checkpoint that relies on the remarkable plasticity and adaptability of tissue-resident commensal-specific T cells. We propose that this feature may also have important implications in the etiology of tissue-specific inflammatory disorders. Based on the extraordinary number of both commensal-derived antigens and T cells at barrier sites, such a feature may represent a fundamental component of host immunity.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) mice were purchased from Taconic Biosciences. Gata3fl/fl (37), Foxp3YFP-Cre (38) and Il17aCre (26) have been previously described and were generously provided by J. Zhu (NIAID, NIH), A. Rudensky (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center), and B. Stockinger (Francis Crick Institute), respectively. Foxp3gfp (39), CD45.1 (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ), Tcra−/− (B6.129S2-Tcratm1Mom/J) (40), CD45.1 Rag1−/−, Il13−/− (41), and CreERT2Gata3fl/fl mice (42) were purchased from the NIAID-Taconic Exchange. Tcra+/− mice were generated by breeding Tcra−/− mice with C57BL/6 WT mice. Foxp3DTR (B6.129(Cg)-Foxp3tm3(DTR/GFP)Ayr/J) (11) and R26ReYFP (B6.129X1-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(EYFP)Cos/J) (43) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. CD4CreIl18r1fl/fl and Il18r1fl/fl control mice were kindly provided by G. Trinchieri (NCI, NIH). All mice were bred and maintained under SPF conditions at an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited animal facility at the NIAID and housed in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All experiments were performed at the NIAID under an Animal Study Proposal (LPD-11E or LPD-68E) approved by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee. Sex- and age-matched mice between 6 and 35 weeks of age were used for each experiment.

Commensal culture and colonization

Staphylococcus epidermidis NIHLM087 (44) was cultured for 18 hours in Tryptic Soy Broth at 37°C. Candida albicans (8) was cultured for 18 hours in Tryptic Soy Broth at 37°C (shaking 180 rpm). For colonization with commensal microbes, as before (45), each mouse was topically associated by placing 5 ml of culture suspension (approximately 109 CFU/ml) across the entire skin surface (approximately 36 cm2) using a sterile swab. Application of commensal microbes was repeated every other day a total of four times. Skin tissue was analyzed 14 days post initial colonization, unless otherwise indicated.

Inducible deletion of Gata3

Deletion of Gata3 in CreERT2Gata3fl/fl mice was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 5 mg tamoxifen in a corn oil–ethanol (90:10) mixture daily for 3 days before cellular isolation and subsequent analysis.

Global Treg cell depletion

Naïve or S. epidermidis-colonized Foxp3DTR mice received ~1 μg (50 μg/kg) diphtheria toxin (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS, or PBS alone, by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection on days 3, 5, 7, and 9 post initial S. epidermidis-colonization. Flow cytometric analysis of skin leukocytes was performed 12 days post initial colonization.

Generation of BowieTg mice

Tcra+/− mice were colonized with S. epidermidis and CD8+CCR6+ T cells were isolated from skin tissue by FACS and subjected to single-cell sequencing of T cell receptor (TCR) alpha and beta chains (46). Clonal TCR pairs were identified and utilized in a hybridoma reconstitution screening assay to identify S. epidermidis-reactive TCR heterodimers. A single S. epidermidis-specific TCR pair were cloned into a hCD2-expression vector (47) and utilized to generate TCR-transgenic mice (BowieTg), to track S. epidermidis-specific T cells in vivo.

Adoptive transfer of BowieTg CD8+ T cells

BowieTg mice were backcrossed to a CD45.1 Rag1−/− background to exclude the possibility of dual TCR expression and facilitate identification of transferred cells. Recipient mice (CD45.2) received 4 × 105 BowieTg CD45.1 Rag1−/− CD8+ T cells by intravenous injection 24 hours prior to the first application of S. epidermidis.

Parabiosis experiments and surgery

Congenically distinct, age- and weight-matched mice were co-housed for 2 weeks prior to colonization with S. epidermidis. Both mice were colonized to control for bacterial spread. Forty days post initial colonization, parabiosis surgery was performed as described (10). Briefly, mice were sedated and longitudinal incisions were made from the elbow to the knee joint of each mouse. Excess skin was removed and mice were joined at the joints. The skin of the two animals was then connected and sutured together. Animals were kept on oral antibiotics for 2 weeks and remained conjoined for 90–95 days before analysis. Analysis was performed on ear pinnae skin tissue.

Acute intradermal challenge

S. epidermidis-colonized mice were anesthetized with ketamine–xylazine and injected intradermally (10 μl/ear pinnae) with either sterile PBS (vehicle control), 250 ng of carrier-free recombinant IL-18 (R&D Systems), or 500 ng of chitin (Sigma Aldrich). Unless otherwise indicated, skin tissue was analyzed for cytokine production potential 48 hours post injury.

Sand fly bite exposure

S. epidermidis-colonized mice were exposed to sand fly bites, as described before (48). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with ketamine–xylazine. Twenty female Lutzomiya longipalpus were transferred to plastic vials (volume 12.2 cm2, height 4.8 cm, diameter 1.8 cm) covered at one end with 0.25 mm nylon mesh. Specially designed clamps were used to bring the mesh end of each vial flat against the ear, allowing flies to feed on exposed skin for a period of 1 hour in the dark at 26°C and 50% humidity. The number of flies with blood meals was employed as a means of checking for equivalent exposure to bites among animals. At indicated time points post exposure, tissues were analyzed for cytokine production.

Ex vivo cytokine screening

CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets from the skin of S. epidermidis or C. albicans-colonized mice were isolated by FACS (> 97% purity) and cultured for 24 hours in the presence of cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-25, IL-33, or TSLP; R&D Systems) (10 ng/ml) and presence or absence of TCR stimulation (1 μg/ml plate bound anti-CD3 mAb, clone 145–2C11). Culture supernatants were assayed for cytokine production by FlowCytomix bead array (eBioscience).

Tissue processing

Cells from the skin-draining lymph nodes, spleen, and ear pinnae were isolated as previously described (6). Cells from lymph nodes and spleen were mashed through a 70-μm cell strainer to generate single-cell suspensions. Ear pinnae were excised and separated into ventral and dorsal sheets. Ear pinnae were digested in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 mM non-essential amino acids, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 mg/ml of streptomycin, and 0.25 mg/ml of Liberase TL purified enzyme blend (Roche), and incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. Digested skin sheets were homogenized using the Medicon/Medimachine tissue homogenizer system (Becton Dickinson).

In vitro re-stimulation

For detection of basal cytokine potential, single cell suspensions from various tissues were cultured directly ex vivo in a 96-well U-bottom plate in complete medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, 20 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol) and stimulated with 50 ng/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5 mg/ml of ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence of brefeldin A (1:1000, GolgiPlug, BD Biosciences) for 3 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. After stimulation, cells were assessed for intracellular cytokine production as described below.

Flow cytometric analysis

Single-cell suspensions were incubated with combinations of fluorophore-conjugated antibodies against the following surface markers: CCR6 (29–2L17), CD3ε (145–2C11), CD4 (RM4–5), CD8β (53–6.7), CD11b (M1/70), CD19 (6D5), CD44 (IM7), CD45 (30-F11), CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), CD69 (H1.2F3), CD103 (2E7), MHCII (M5/114.15.2), TCRβ (H57–597) and/or Thy1.2 (30-H12) in Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS) for 20 min at 4°C (RT for 30 min for CCR6) and then washed. LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used to exclude dead cells. Cells were then fixed for 30 min at 4°C using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (Becton Dickinson) and washed twice. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies against IFN-γ (XMG-1.2), IL-5 (TRK5), IL-13 (eBio13A), and IL-17A (eBio17B7) in BD Perm/Wash Buffer (Becton Dickinson) for 60 min at 4°C. For transcription factor staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with the Foxp3/Transcription Factor staining buffer set (eBioscience) and stained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies against Foxp3 (FJK-16s), GATA-3 (L50–823 or TWAJ), RORγt (B2D), or T-bet (eBio4B10) for 45 min at 4°C. Each staining was performed in the presence of purified anti-mouse CD16/32 (clone 93) and purified rat gamma globulin (Jackson Immunoresearch). All antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, Biolegend, BD Biosciences, or Miltenyi Biotec. Cell acquisition was performed on a BD Fortessa X-20 flow cytometer using FACSDiVa software (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

RNA staining

Skin tissue single-cell suspensions were analyzed for mRNA and protein expression using the PrimeFlow RNA assay (eBioscience) and standard mouse probesets for Ifng, Il5, Il13, and Il17a, as per manufacturer’s instructions for 96-well-plate staining.

Tetramer-based cell enrichment

f-MIIINA:H2-M3-specific CD8+ T cells from secondary lymphoid organs were subjected to magnetic bead based enrichment, as previously described (49). Briefly, spleen and lymph node cells from parabiotic pairs were stained for 1 hour at room temperature with f-MIIINA:H2-M3-streptavidin-phycoerythrin (PE) tetramer. Samples were then incubated with anti-PE beads (Miltenyi Biotech) and enriched for bead-bound cells on magnetized columns.

RNA-sequencing and transcriptome analysis

T cells were isolated by flow cytometric cell sorting from the ear skin tissue of C57BL/6 mice 2 weeks after colonization with S. epidermidis NIHLM087. Groups included: Tc1 (Viable Lineage−CD45+CD90.2+CD8β+CCR6−) and Tc17 cells (Viable Lineage−CD45+CD90.2+CD8β+CCR6+). Sorted cells were lysed in Trizol reagent and total RNA isolated by phenol–chloroform extraction with GlycoBlue as a co-precipitant (7 μg per sample; Life Technologies). Single-end libraries were prepared with 0.25–1 μg of total RNA using the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit V2 and sequenced for 50 cycles with a HiSeq 2500 instrument (4–6 samples multiplexed per lane; Illumina). Sequencing quality of the raw read data was assessed using FASTQC v0.11.5. Using a custom Perl script, 10 bp were trimmed from the 3′ end of the 50-bp reads. Subsequently, FASTQ files were used as input for RSEM v1.3.0 (50) (internally configured to use the bowtie aligner, v1.1.1). Expected read counts from RSEM were imported into the DESeq2 Bioconductor package (51), normalized using the geometric-mean based approach built into this package and then tested for differential expression between groups using a Wald test with multiple testing correction using the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery.

ATAC sequencing and epigenome analysis

T cells were isolated as for RNA sequencing. ATAC-seq was performed according to a published protocol (16). ATAC-seq reads from two biological replicates for each sample were mapped to the mouse genome (mm10 assembly) using STAR (52). Duplicate reads were removed using FastUniq (53), and reads mapping to mitochondrial loci removed based upon ENCODE blacklists. Regions of open chromatin were identified by MACS (version 1.4.2) using a p-value threshold of 1 × 10−5. Only regions called in both replicates were used in downstream analysis. Downstream analysis and heatmap generation were performed with the Hypergeometric Optimization of Motif EnRichment program (HOMER) version 4.8 (54).

Single cell RNA sequencing

T cells were isolated as for bulk RNA sequencing, from S. epidermidis-colonized IL-17A-fate-mapping mice, with three groups: Tc1 (Viable Lineage−CD45+CD90.2+CD8β+CCR6−), Tc17 IL-17AFM− (Viable Lineage−CD45+CD90.2+CD8β+CCR6+eYFP−) and Tc17 IL-17AFM+ (Viable Lineage−CD45+CD90.2+CD8β+CCR6+eYFP+). Freshly isolated cells were encapsulated into droplets, and libraries prepared using Chromium Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kits v2 (10X Genomics). The generated scRNA-seq libraries were sequenced using 26 cycles of Read 1, 8 cycles of i7 Index, and 98 cycles of Read2 with a HiSeq 3000 (Illumina).

Single cell RNA sequencing analysis

Sequence reads were processed and aggregated using Cell Ranger software. Aggregated data was further analyzed using Seurat (55).

Confocal microscopy

Ear pinnae were split with forceps, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS (Electron Microscopy Sciences) overnight at 4°C and blocked in 1% BSA + 0.25% Triton X in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature. Tissues were first stained with anti-CD4 (RM4–5, eBioscience), anti-CD8α (clone 53–6.7, eBioscience), anti-CD45.1 (A20, eBioscience), anti-CD49f (GoH3, eBioscience) and/or anti-GFP (A21311, Life Technologies) antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed three time with PBS and then stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich) overnight before being mounted with ProLong Gold (Molecular Probes) antifade reagent. Ear pinnae images were captured on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope equipped with HyD and PMT detectors and a 40× oil objective (HC PL APO 40X/1.3 oil). Images were analyzed using Imaris software (Bitplane).

Back-skin wounding and epifluorescence microscopy of back-skin wounds

Tissue wounding and quantitation of wound healing were performed as previously described (56). Briefly, male mice in the telogen phase of the hair cycle were anesthetized and punch biopsies performed on back skin. Dorsal hair was shaved with clippers and a 6mm biopsy punch was used to partially perforate the skin. Iris scissors were then used to cut epidermal and dermal tissue to create a full thickness wound in a circular shape. Back-skin tissue was excised 5 days post wounding, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, incubated overnight in 30% sucrose in PBS, embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek), frozen on dry ice, and cryo-sectioned (20-μm section thickness). Sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, rinsed with PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (Sigma Aldrich), and blocked for 1 hour in blocking buffer (2.5% Normal Goat Serum, 1% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS). Primary antibody to Keratin 14 (chicken, Poly9060, 1:400, Biolegend) was diluted in blocking buffer with rat gamma globulin and anti-CD16/32 and incubated overnight. After washing with PBS, a secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa647 (goat anti-chicken, Jackson ImmunoResearch) was added for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were washed with PBS, counterstained with DAPI and mounted in Prolong Gold. Wound images were captured with a Leica DMI 6000 widefield epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Leica DFC360X monochrome camera. Tiled and stitched images of wounds were collected using a 20×/0.4NA dry objective. Images were analyzed using Imaris software (Bitplane).

In vivo cytokine blockade

Naïve or S. epidermidis-colonized WT or Il13−/− mice received 0.5 mg of anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibody (clone 262A-5–1, Genentech) or mouse IgG1 isotype control (clone MOPC-21, BioXCell), or 1 mg of anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody (clone TRFK5, BioXCell) or rat IgG1 isotype control (clone TNP6A7, BioXCell), or 1 mg of anti-IL-18 monoclonal antibody (clone SK113AE-4 (57)) or isotype control by i.p. injection 1 day prior to skin injury.

Total tissue RNA-seq

A ~1-mm skin region surrounding the wound site was micro-dissected at indicated timepoints after wounding, submerged in RNAlater (Sigma Aldrich) and stored at −20°C. Total tissue RNA was isolated from skin tissue using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini kit (Qiagen), as per manufacturer’s instructions. A 3′ mRNA sequencing library was prepared using 200–500 ng of total input RNA with the QuantSeq 3′ mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit FWD for Illumina (Lexogen) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were quantified using an Agilent Tapestation (High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape) and Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Libraries (n = 20) were pooled at equimolar concentrations and sequenced on an Illumina Nextseq 500 using the High Output v2 kit (75 cycles). Resultant data was demultiplexed on Illumina Basespace server using blc2fastq tool. The reads from the Illumina Next-seq sequencer in fastq format were verified for quality control using FastQC software package, aligned to mouse GRCM38 using RSEM package (50) calling STAR aligner (52). The RSEM expected counts were rounded to the nearest integer value and the transcripts with zero counts across all samples filtered out. Differential expression analysis and PCA was performed using DESeq2 (51).

Statistics

Groups were compared with Prism V7.0 software (GraphPad) using the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA with Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparison test, or two-way ANOVA with Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparison test where appropriate. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank the NIAID animal facility staff; K. Holmes, E. Stregevsky, and T. Hawley (NIAID Flow Cytometry facility); G. Gutierrez-Cruz, S. Dell’Orso, and H-W. Sun, (NIAMS Genome Analysis Core facility); J. Kehr for editorial assistance; and K. Beacht, and S. Mistry for technical assistance. We thank Prof. I. Förster (University of Bonn) for generous provision of the anti-IL-18 hybridoma. f-MIIINA:H2-M3-tetramer reagents were obtained from the NIH Tetramer Core Facility. This study used the Office of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology (OCICB) High Performance Computing (HPC) cluster at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Bethesda, MD and the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the NIH.

Funding: Y.B. was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; ZIA-AI001115, ZIA-AI001132). J.J.O. was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS; ZIA-AR041159, ZIA-AR041167). O.J.H. was supported in part by a National Psoriasis Foundation Early Career Research Grant. J.L.L. was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Postdoctoral Research Associate (PRAT) fellowship program. S.T. was supported in part by a European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) fellowship. C.H. was supported in part by Collège des Enseignants de Dermatologie Français, Société Française de Dermatologie, Philippe Foundation, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions: O.J.H. and Y.B. designed the study, experiments, and wrote the manuscript. O.J.H. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.L.L., S.-J.H., N.B., H.-Y.S., M.S., S.K.S., A.L.B., M.E., S.T., F.V.L., C.H., N.C., A.P., R.S., and J.J.O. participated in performing experiments, provided intellectual expertise, and helped to interpret experimental results. J.L.L. generated BowieTg mice, performed wounding experiments, and analyzed data. H.-Y.S., S.K.S., A.L.B., and C.Y. assisted with RNA-seq and ATAC-seq studies. N.B. and S.T. performed flow-cytometric analysis of skin immune cells; S.J.H. performed confocal microscopy analysis; M.S. performed epifluorescence microscopy of wounds; M.E. assisted with wounding experiments; and S.J.H. and N.C. performed parabiotic surgeries. F.V.L. shared expertise for the generation of TCR-expressing hybridomas and TCR-transgenic mice. A.P. conducted sand fly exposures and C.H. performed C. albicans experiments.

Data and materials availability: Anti-IL-13 (clone 262A-5–1) is available under a material agreement with Genentech. Anti-IL-18 (clone SK113AE-4) is available from Prof. Irmgard Förster under a material agreement with University of Bonn. The accession number for the RNA-Seq and ATAC-Seq datasets is NCBI BioProject: PRJNA486019. All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in this paper are present either in the main text or the Supplementary Materials.

References and Notes:

- 1.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO, A dominant, coordinated T regulatory cell-IgA response to the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 19256–19261 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hand TW et al. , Acute gastrointestinal infection induces long-lived microbiota-specific T cell responses. Science 337, 1553–1556 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y et al. , Focused specificity of intestinal TH17 cells towards commensal bacterial antigens. Nature 510, 152–156 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naik S et al. , Commensal-dendritic-cell interaction specifies a unique protective skin immune signature. Nature 520, 104–108 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belkaid Y, Harrison OJ, Homeostatic Immunity and the Microbiota. Immunity 46, 562–576 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linehan JL et al. , Non-classical Immunity Controls Microbiota Impact on Skin Immunity and Tissue Repair. Cell 172, 784–796 e718 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scharschmidt TC et al. , A Wave of Regulatory T Cells into Neonatal Skin Mediates Tolerance to Commensal Microbes. Immunity 43, 1011–1021 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridaura VK et al. , Contextual control of skin immunity and inflammation by Corynebacterium. J Exp Med 215, 785–799 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schenkel JM, Masopust D, Tissue-resident memory T cells. Immunity 41, 886–897 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright DE, Wagers AJ, Gulati AP, Johnson FL, Weissman IL, Physiological migration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Science 294, 1933–1936 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY, Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol 8, 191–197 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wohlfert EA et al. , GATA3 controls Foxp3(+) regulatory T cell fate during inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest 121, 4503–4515 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delacher M et al. , Genome-wide DNA-methylation landscape defines specialization of regulatory T cells in tissues. Nat Immunol 18, 1160–1172 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Su MA, Wan YY, An essential role of the transcription factor GATA-3 for the function of regulatory T cells. Immunity 35, 337–348 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudra D et al. , Transcription factor Foxp3 and its protein partners form a complex regulatory network. Nat Immunol 13, 1010–1019 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shih HY et al. , Developmental Acquisition of Regulomes Underlies Innate Lymphoid Cell Functionality. Cell 165, 1120–1133 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee GR, Fields PE, Griffin TJ, Flavell RA, Regulation of the Th2 cytokine locus by a locus control region. Immunity 19, 145–153 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang HE et al. , Divergent expression patterns of IL-4 and IL-13 define unique functions in allergic immunity. Nat Immunol 13, 58–66 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohrs K, Wakil AE, Killeen N, Locksley RM, Mohrs M, A two-step process for cytokine production revealed by IL-4 dual-reporter mice. Immunity 23, 419–429 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang CH et al. , Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell 153, 1239–1251 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araki K et al. , Translation is actively regulated during the differentiation of CD8(+) effector T cells. Nat Immunol 18, 1046–1057 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salerno F et al. , Translational repression of pre-formed cytokine-encoding mRNA prevents chronic activation of memory T cells. Nat Immunol, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonilla WV et al. , The alarmin interleukin-33 drives protective antiviral CD8(+) T cell responses. Science 335, 984–989 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamoto I, Kohno K, Tanimoto T, Ikegami H, Kurimoto M, Development of CD8+ effector T cells is differentially regulated by IL-18 and IL-12. J Immunol 162, 3202–3211 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahern PP et al. , Interleukin-23 drives intestinal inflammation through direct activity on T cells. Immunity 33, 279–288 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirota K et al. , Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol 12, 255–263 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang YH et al. , A novel subset of CD4(+) T(H)2 memory/effector cells that produce inflammatory IL-17 cytokine and promote the exacerbation of chronic allergic asthma. J Exp Med 207, 2479–2491 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panzer M et al. , Rapid in vivo conversion of effector T cells into Th2 cells during helminth infection. J Immunol 188, 615–623 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irvin C et al. , Increased frequency of dual-positive TH2/TH17 cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid characterizes a population of patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 134, 1175–1186 e1177 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirota K et al. , Plasticity of Th17 cells in Peyer’s patches is responsible for the induction of T cell-dependent IgA responses. Nat Immunol 14, 372–379 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gagliani N et al. , Th17 cells transdifferentiate into regulatory T cells during resolution of inflammation. Nature 523, 221–225 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Okamura H, Interleukin-18 regulates both Th1 and Th2 responses. Annu Rev Immunol 19, 423–474 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison OJ et al. , Epithelial-derived IL-18 regulates Th17 cell differentiation and Foxp3(+) Treg cell function in the intestine. Mucosal Immunol 8, 1226–1236 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arpaia N et al. , A Distinct Function of Regulatory T Cells in Tissue Protection. Cell 162, 1078–1089 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ricardo-Gonzalez RR et al. , Tissue signals imprint ILC2 identity with anticipatory function. Nat Immunol, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eming SA, Wynn TA, Martin P, Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration. Science 356, 1026–1030 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu J et al. , Conditional deletion of Gata3 shows its essential function in T(H)1-T(H)2 responses. Nat Immunol 5, 1157–1165 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubtsov YP et al. , Stability of the regulatory T cell lineage in vivo. Science 329, 1667–1671 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bettelli E et al. , Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441, 235–238 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mombaerts P et al. , Mutations in T-cell antigen receptor genes alpha and beta block thymocyte development at different stages. Nature 360, 225–231 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKenzie GJ et al. , Impaired development of Th2 cells in IL-13-deficient mice. Immunity 9, 423–432 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yagi R et al. , The transcription factor GATA3 is critical for the development of all IL-7Ralpha-expressing innate lymphoid cells. Immunity 40, 378–388 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srinivas S et al. , Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol 1, 4 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conlan S et al. , Staphylococcus epidermidis pan-genome sequence analysis reveals diversity of skin commensal and hospital infection-associated isolates. Genome Biol 13, R64 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naik S et al. , Compartmentalized control of skin immunity by resident commensals. Science 337, 1115–1119 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dash P et al. , Paired analysis of TCRalpha and TCRbeta chains at the single-cell level in mice. J Clin Invest 121, 288–295 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun G et al. , The zinc finger protein cKrox directs CD4 lineage differentiation during intrathymic T cell positive selection. Nat Immunol 6, 373–381 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimblin N et al. , Quantification of the infectious dose of Leishmania major transmitted to the skin by single sand flies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 10125–10130 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moon JJ et al. , Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity 27, 203–213 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li B, Dewey CN, RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 323 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dobin A et al. , STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu H et al. , FastUniq: a fast de novo duplicates removal tool for paired short reads. PLoS One 7, e52249 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heinz S et al. , Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 38, 576–589 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, Satija R, Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat Biotechnol 36, 411–420 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keyes BE et al. , Impaired Epidermal to Dendritic T Cell Signaling Slows Wound Repair in Aged Skin. Cell 167, 1323–1338 e1314 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lochner M, Wagner H, Classen M, Forster I, Generation of neutralizing mouse anti-mouse IL-18 antibodies for inhibition of inflammatory responses in vivo. J Immunol Methods 259, 149–157 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.