Abstract

Background

Metastatic duodenopancreatic neuro-endocrine tumors (dpNETs) are the most important disease-related cause of death in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). Nonfunctioning pNETs (NF-pNETs) are highly prevalent in MEN1 and clinically heterogeneous. Therefore, management is controversial. Data on prognostic factors for risk stratification is limited. This systematic review aims to establish the current state of evidence regarding prognostic factors in MEN1-related NF-pNETs.

Methods

We systematically searched four databases for studies assessing prognostic value of any factor on NF-pNET progression, development of distant metastases, and/or overall survival. In- and exclusion, critical appraisal and data-extraction were performed independently by two authors according to pre-defined criteria.

Results

Thirteen studies (370 unique patients) were included. Prognostic factors investigated were tumor size, timing of surgical resection, WHO grade, methylation, p27/p18 expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC), ARX/PDX1 IHC and alternative lengthening of telomeres. Results were complemented with evidence from studies in MEN1-related pNET for which data could not be separately extracted for NF-pNET and data from sporadic NF-pNET.

Conclusion

The most important prognostic factors used in clinical decision making in MEN1-related NF-pNETs are tumor size and grade. NF-pNETs <2 cm may be managed with watchful waiting, while surgical resection is advised for NF-pNETs ≥ 2cm. Grade 2 NF-pNETs should be considered high risk. The most promising and MEN1-relevant avenues of prognostic research are multianalyte circulating biomarkers, tissue based molecular factors and imaging-based prognostication. Multi-institutional collaboration between clinical, translation and basic scientists with uniform data and biospecimen collection in prospective cohorts should advance the field.

Keywords: MEN1, Prognostic factors, Nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, Systematic review, Survival, Metastases

Introduction

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is a rare hereditary endocrine tumor syndrome caused by germline pathogenic variants in the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene encoding for the menin protein (Chandrasekharappa et al., 1997, Lemmens et al., 1997). During the course of life, carriers of a germline mutation in the MEN1 gene will acquire somatic mutations inactivating the healthy copy of the gene leading to hyperplasia and tumor formation in multiple endocrine and non-endocrine tissues. Primary affected organs are the parathyroid (presenting feature in 90% of the cases), the neuroendocrine pancreas and duodenum, and the pituitary.

Duodenopancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (dpNETs) are highly prevalent in MEN1 (Triponez et al., 2006a, de Laat et al., 2016) and distant metastases are the most important MEN1-related cause of death (Goudet et al., 2010). Of the dpNETs encountered in MEN1, nonfunctioning (NF) tumors are the most frequent, with a prevalence of 50% at the age of 50 (Triponez et al., 2006a) and up to 42% in patients <21 years (Machens et al., 2007, Vannucci et al., 2018, Goncalves et al., 2014, Goudet et al., 2015, Manoharan et al., 2017, Triponez et al., 2006a). There is currently no agreement on interventions and timing thereof in MEN1-related NF-pNETs. Because of pre-symptomatic genetic testing and subsequent surveillance, NF-pNETs in patients with MEN1 are diagnosed more often, at an earlier age and at an earlier stage and their management presents a challenge to patients and physicians. The only curative treatment is surgical resection, which is associated with significant morbidity (Nell et al., 2016), and new NF-pNETs will invariably occur in any remnant pancreas tissue left behind. Recently, multiple retrospective cohorts have reported on the indolent course of most small (<2cm) NF-pNETs (Pieterman et al., 2017, Triponez et al., 2006a, Triponez et al., 2006b, van Treijen et al., 2018). However, subgroups of small NF-pNETs with faster growth are identified, and even small NF-pNETs can metastasize despite seemingly reassuring characteristics (Pieterman et al., 2017). Reliable estimation of prognosis in MEN1-related NF-pNETs is important to inform management decisions in these patients. We therefore systemically reviewed and critically appraised the present literature on prognostic factors for the outcome of NF-pNETs in patients with MEN1. In a comprehensive narrative review, Lee et al. recently provided a general overview of prognostic factors in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (Lee et al., 2019). We further aim to compare prognostic factors originating from evidence in sporadic (NF-) pNETs to evidence in MEN1, and comment on the factors that have not been investigated in MEN1.

Methods

Search Strategies

The electronic databases PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase.com, Cochrane Library: CENTRAL and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Web of Science: Core Collection were searched in May and June/July 2019 by a biomedical librarian. Two searches were conducted using a combination of keywords and controlled vocabulary terms for each concept of interest (e.g., “Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1”, MEN1, “nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor”, pancreatic tumor, neuroendocrine tumor). The complete search string is documented in Supplemental Material 1. The first search (May) was more focused, including “nonfunctioning” as a search term. A second, broader search (June/July) that did not specify the type of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor was later completed to ensure that all relevant literature on neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors and MEN1 were retrieved. Search results were limited to those published in Dutch, English, French, and German from 2001 to 2019. The 2001 cut-off point was chosen to represent the era in which pre-symptomatic genetic testing for an MEN1 mutation is possible and guidelines are in place for recommended surveillance.

Study Selection

Original studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses assessing the prognostic value of any factor on NF-pNET progression, development of distant metastases, and/or overall survival were eligible for inclusion. Progression could be either growth of existing tumors or development of lymph node or distant metastases. Studies that considered the development of new pNETs to be progression were also included. Studies including both sporadic and MEN1-related NF-pNETs or both functioning and NF-pNETs were eligible if it was possible to extract data for MEN1-related NF-pNETs separately. To minimize selection bias, studies with five or fewer patients with MEN1-related NF-pNET were excluded. All identified articles were independently screened on title and abstract by two authors (S.M.S. and C.R.C.P). Thereafter, independent full-text reviews of potentially relevant studies were performed, and studies were selected if eligibility criteria were fulfilled (S.M.S. and C.R.C.P.). Authors resolved any disagreements by consensus and, when unsuccessful, with the help of a third and fourth reviewer (G.D.V. and F.T.). Reasons for exclusion at full-text screening were recorded. All included articles were cross-referenced for additional relevant articles.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Included articles were critically appraised using a modified Quality Assessment in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) tool (Supplemental Material 2) (Hayden et al., 2006, Hayden et al., 2013). Articles were judged on five important domains: study participation, study attrition, prognostic factor measurement, outcome measurement, and statistical analysis and reporting. Critical appraisal was performed independently by two authors (S.M.S. and C.R.C.P), and afterwards, consensus was reached for final decisions. To avoid bias S.M.S. and F.T. performed the critical appraisal of the paper for which C.R.C.P. was first author.

Data extraction

Study and patient characteristics were retrieved from the included articles. Data was extracted independently by two authors (S.M.S. and C.R.C.P.) as to the study population, baseline characteristics, distribution and measurement of the prognostic factor and outcome, statistical analysis used, and the prognostic value of the investigated factor(s) according to a predefined data-extracting sheet designed by the authors (Supplemental Material 3).

Results

Retrievals and inclusion

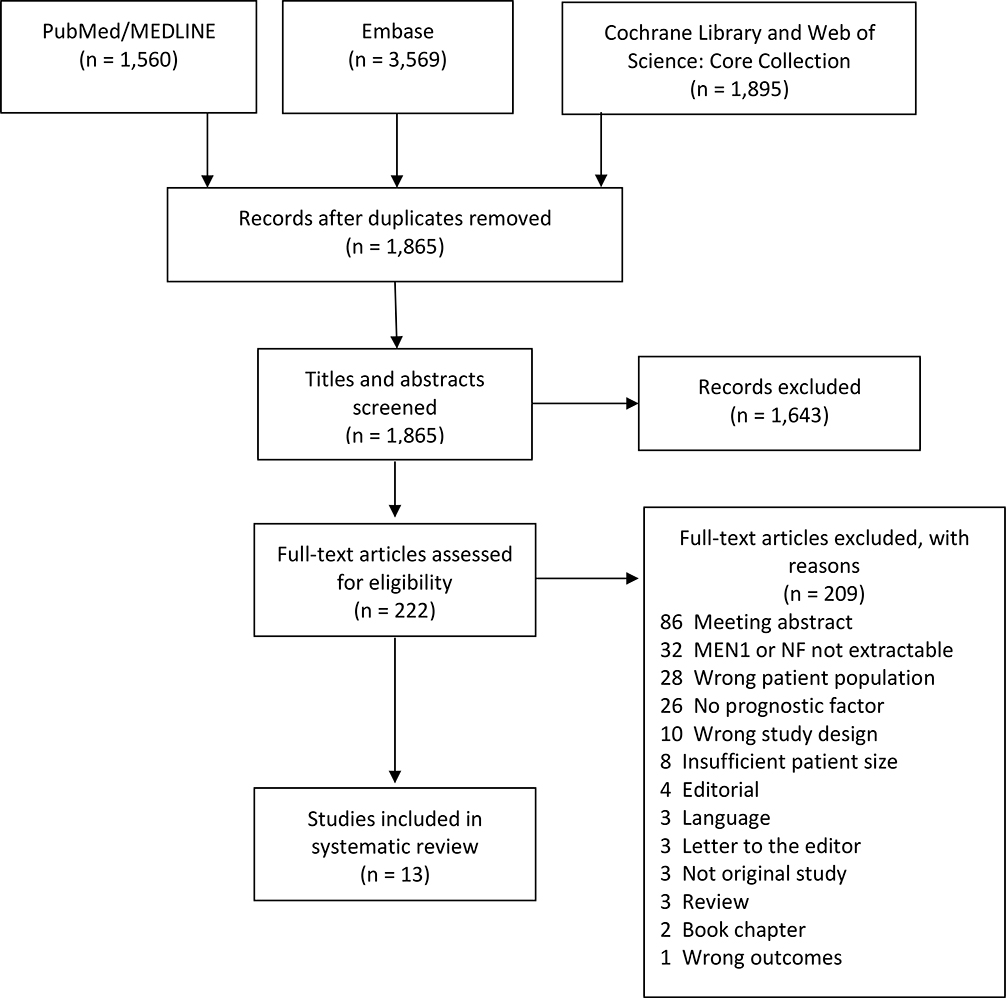

A total of 7,024 citations were retrieved from the literature searches (Figure 1). Of these, 5,159 were duplicate citations. A total of 1,865 citations were screened. After title and abstract screening, 1,643 citations were deemed irrelevant (inter-rater agreement good, Cohen kappa 0.74). Of a total of 222 citations, the full texts were reviewed, after which 209 citations were excluded (inter-rater agreement good, Cohen kappa 0.78). Ultimately, only thirteen papers could be included in the risk of bias assessment (Table 1) (Bartsch et al., 2005, Cejas et al., 2019, Conemans et al., 2017a, Conemans et al., 2018a, Conemans et al., 2018b, Davi et al., 2011, D’Souza S et al., 2014, Nell et al., 2018, Partelli et al., 2016, Pieterman et al., 2017, Sakurai et al., 2007, Triponez et al., 2006a, Triponez et al., 2006b). A reference search performed on these 13 papers did not yield additional papers to be included.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for identified studies.

Table 1:

Risk of Bias for Included Studies Assessing the Prognostic Factors in MEN1

| Author yr, ref | Study participation1 | Study attrition2 | Prognostic Factor Measurement3 | Outcome measurement3 | Statistical Analysis and Reporting4 | Overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Bartsch et al., 2005) | + | + | − | − | − | High |

| (Cejas et al., 2019) | + | ? | + | − | + | Moderate |

| (Conemans et al., 2018a) DNA methylation profiling | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| (Conemans et al., 2018b) p27Kip1 and p18Ink4c | + | ? | + | + | − | Moderate |

| (Conemans et al., 2017a) WHO grade | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| (Davi et al., 2011) | + | + | − | + | + | Moderate |

| (D’Souza S et al., 2014) | − | ? | + | + | + | Moderate |

| (Nell et al., 2018) | + | ? | + | + | + | Low |

| (Partelli et al., 2016) | + | ? | + | Distant metastases: + Progression-free survival: − |

+ | Moderate |

| (Pieterman et al., 2017) | + | + | + | + | + | Low |

| (Sakurai et al., 2007) | + | ? | − | − | − | High |

| (Triponez et al., 2006b) is surgery beneficial ≤ 2cm | + | − | + | − | + | High |

| (Triponez et al., 2006a) Epidemiology data on 108 MEN1 NF-pNET | + | ? | Tumor size - Surgery + | − | + | High |

Symbols: + low risk of bias; − high risk of bias; ? unclear

In study participation, we judged the percentage of the population with MEN1-related NF-pNETs, whether the study population truly represents MEN1 patients as diagnosed according to the guidelines, the sample frame and recruitment, description of source population, and baseline characteristics.

Study attrition assessed loss to follow-up and whether this could have biased the relationship between prognostic factor and outcome.

For prognostic factor and outcome measurement, we assessed whether the measurement was clearly described, if the measurement was valid (according to predefined criteria), and whether the measurement was performed according to the same procedure in all participants.

For statistical analysis, we assessed whether this was adequately described, appropriate, and if there was no selective reporting. See also Supplemental Material 2.

Overview of included studies

We included 13 retrospective studies (from 2 nationwide multicenter cohorts, 1 multi-institutional cohort and 4 single-center cohorts) encompassing 370 unique patients since the same patients were described in multiple studies (Bartsch et al., 2005, Davi et al., 2011, Cejas et al., 2019, Conemans et al., 2017a, Conemans et al., 2018a, Conemans et al., 2018b, D’Souza S et al., 2014, Nell et al., 2018, Partelli et al., 2016, Pieterman et al., 2017, Sakurai et al., 2007, Triponez et al., 2006a, Triponez et al., 2006b). A summary of the characteristics and outcomes of the included studies can be viewed in Table 2, more detailed information is available in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. The studies were of predominantly European origin. Most (9/13) were multi-center studies. With exception of one study (Partelli et al., 2016) follow-up was less than 10 years in all, ranging from 2–7 years. Six of the multicenter studies were from the DutchMEN Study Group (DMSG) and included in part the same patient population (Conemans et al., 2017a, Cejas et al., 2019, Conemans et al., 2018a, Conemans et al., 2018b, Nell et al., 2018, Pieterman et al., 2017). More specifically, the three papers from Conemans at al. investigated different factors in the same cohort of surgically resected NF-pNETs and this cohort was also used by Cejas et al. The paper of Nell et al. on surgery in MEN1-related NF-pNETs includes the same patients as Pieterman et al. and also the same surgical cohort as the paper by Conemans et al. The two included papers from the Groupe d’étude des Tumeurs Endocrines (GTE) (Triponez et al., 2006a, Triponez et al., 2006b), a collaborative endocrine tumor research group from France and Belgium, also in part reported on the same population. Specifically, the 65 patients with NF-pNETs <2cm described by Triponez et al.(Triponez et al., 2006b) were also included in the previous study on 108 patients with MEN1 and isolated NF-pNETs (Triponez et al., 2006a). Most studies were not specifically designed as prognostic studies.

Table 2:

Characteristics and Outcomes of Included Studies

| Author, yr, country | Study design and follow-up | Study population | Prognostic factors analyzed | Outcome measurement | Results: prognostic value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Bartsch et al., 2005) Germany | Retrospective single center f/u 3.6 y (0.4–11.6) |

n=26 MEN1 + pancreatic surgery n=9 NF-pNET |

Tumor size | Metastatic potential | NF-pNET: No correlation between size and metastatic potential (P>0.5) |

| (Cejas et al., 2019) USA, The Netherlands | Retrospective multi center f/u median 2 y |

n=61 MEN1 + pancreatic surgery n=47 NF-pNET |

(1) ARX and PDX1 (2) ALT status |

Distant metastases | Liver relapses (n=9) only in ARX+ or ARX-/PDX1- cases HR for distant recurrence in MEN1 NF-pNET 7.1 for ARX+ (P=0.03) compared to PDX1+ cases For all cases (sporadic/MEN1) only ALT and ARX+/double negative were independently associated with occurrence of distant relapse |

| (Conemans et al., 2018b) The Netherlands | Retrospective multi center f/u median 5.8 y |

n=61 MEN1 + pancreatic surgery n=46 NF-pNET |

IHC expression of p27kip1 and p18ink4c | LM | No significant association between p27kip1 and p18ink4c IHC and clinical and pathological characteristics |

| (Conemans et al., 2018a) The Netherlands | Retrospective multi center f/u median 5.8 y |

n=61 MEN1 + pancreatic surgery n=47 NF-pNET |

CMI | LM | Higher CMI in NF-pNETs with LM (P=0.013) |

| (Conemans et al., 2017a) The Netherlands | Retrospective multi center f/u mean 6.6 y |

n=69 MEN1 + pancreatic surgery n=53 NF-pNET |

(1) Tumor size (2) Mitotic index (3) KI-67 (4) WHO grade |

LM | Tumor grade based on KI-67 or combination of KI-67 and mitotic index, not significantly associated with LM Based on mitotic index grade significantly associated with LM: KM survival data 5 y (P=0.000): ≤ 2 cm: 100% free of LM >2 cm Grade 1: 90% free of LM >2 cm Grade 2: 40% free of LM |

| (Davi et al., 2011) Italy | Prospective single center cohort, retrospective analysis f/u N/A1 |

n=31 MEN1 + dpNET n=16 NF-pNET n=8 ww n=8 surgery |

Tumor Size | Metastases | For patients with NF-pNET who underwent surgery: No correlation between tumor size and metastases (P=0.21). NF-pNET <2cm: 0% metastases For patients conservatively treated: n=8 stable, no metastases after median 2 y (1–10) |

| (D’Souza S et al., 2014) USA | Retrospective single center f/u mean 6.6 y |

n=11 MEN1 NF-PNET | Existing or new lesions | Tumor growth | Growth rate differs significantly between existing and new lesions (P=0.01) |

| (Nell et al., 2018) The Netherlands | Retrospective multi center median f/u ww: 7.2 y surgery: 4.5 y |

n=152 MEN1 NF-pNET n=99 ww n=53 surgery |

Surgery versus ww | Metastasis-free survival | Propensity Score-adjusted HR (ww=1): Surgery 0.73 (95% CI 0.25–2.11) Surgery <2 cm: 2.04 (95% CI 0.31–13.59) Surgery 2–3 cm: 1.38 (95% CI 0.09–20.31) Surgery >3 cm N/A >3 cm: 5/6 (83%) managed with ww developed LM vs. 6/16 (38%) who underwent surgery |

| (Partelli et al., 2016) Italy, Germany, UK | Retrospective multi center median f/u: ww: 9.1 y Surgery: 10.6 y |

n=60 MEN1 NF-pNET <2 cm n=33 ww n=27 surgery |

Surgery versus ww Decision at initial diagnosis |

Distant metastases PFS |

PFS not different between ww and surgery (P=0.2) Development of new metastases (P=1), pNET-related death (P=0.9), and tumor enlargement during f/u (P=0.2) not different between ww and surgery |

| (Pieterman et al., 2017) The Netherlands | Retrospective longitudinal multi center f/u median 5y |

n=99 MEN1 + NF-pNET <2cm (n=115 tumors) | Genotype Age Hypergastrinemia Existing/new tumor Baseline size Gender |

Growth rate (mm/y) | Overall (n=115) no association prognostic factors and growth rate No difference in age, gender, genotype, hypergastrinemia, new tumors and baseline size between progressive and stable tumors Stratified analysis of progressive tumors: tumors with germline missense mutations faster growth (P=0.09). Other factors not significant. |

| (Sakurai et al., 2007) Japan | Retrospective single center f/u mean 6.5y |

n=14 MEN1 and NF-pNET | Tumor size | Metastases | n=5/6 (83%) >35 mm newly developed tumors or metastases n=1/8 (13%) <35 mm newly developed tumors |

| (Triponez et al., 2006a) France and Belgium | Retrospective multi center f/u mean 4.3 y |

n=108 MEN1 NF-pNET | Tumor size Surgery |

OS Metastases |

Larger tumor size associated with metastases (p<0.01) 0–30 mm better survival compared to >30 mm (p<0.01) no difference between <10 mm and 10–30 mm (P=0.31) Survival worse in non-curative surgery (p<0.01) Survival not different between curative surgery vs ww (P=0.15) |

| (Triponez et al., 2006b) France and Belgium | Retrospective multi center mean f/u: ww: 3.3y mean 6.7 y |

n=65 MEN1 NF-pNET ≤ 2 cm n=50 ww n=15 surgery |

Surgery vs. ww | OS DFS |

No significant difference in progression and death between surgery and ww Overall life expectancy in patients with NF-pNET <2 cm not different than n=229 MEN1 patients without any dpNET (P=0.33) |

Not separately reported for NF-pNET

More detailed information on study characteristics and outcomes can be found in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Abbreviations: ALT alternative lengthening of telomeres CMI cumulative methylation index DFS disease-free survival dpNET duodenopancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, f/u follow-up HR hazard ratio IHC immunohistochemistry LM liver metastases MEN1 multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 n number N/A not available NF-pNET non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor OS overall survival PFS progression-free survival pNET pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor UK United Kingdom USA United States of America WHO world health organization ww watchful waiting y year

Outcomes of included studies (Table 2)

Prognostic value of clinical factors: tumor size and size criteria for surgical intervention

Four studies investigated tumor size as a prognostic factor for NF-pNETs in MEN1 (see Table 2) (Bartsch et al., 2005, Davi et al., 2011, Sakurai et al., 2007, Triponez et al., 2006a). The development of metastases was the primary endpoint in three, and development of new lesions in one (Sakurai et al., 2007). Studies were at moderate to high risk of bias (Table 1), as attributable risks could often not be calculated. Three studies compared surgical resection of NF-pNETs with a watchful waiting strategy based on tumor size (Table 2) (Nell et al., 2018, Partelli et al., 2016, Triponez et al., 2006b). Overall survival and/or disease-, metastases- or progression-free survival were the primary endpoints.

Two studies reported that tumor size was not associated with metastases. Bartsch et al. (n=9, median follow-up 3.6y), did not find a correlation between tumors size and metastatic potential. This study did however have a small sample size, short follow-up and high risk of bias (Bartsch et al., 2005). Davi et al. (n=16, follow-up not available for NF-pNET, moderate risk of bias) report no correlation between tumor size and metastases (lymph node (ln) + distant), however only in those that underwent surgical resection (n=8). When looking at the entire study population no metastases were seen in patients with tumors <2 cm (Davi et al., 2011).

In contrast, Triponez et al. (n=108, follow-up 4.3 years after pNET diagnosis, high risk of bias) found larger tumor size to be correlated with risk of metastases (ln + distant) and worse survival (Triponez et al., 2006a). Sakurai et al. (n=14, follow-up 6.5 years, high risk of bias) found a tumor size >35 mm to be associated with more newly developed tumors (Sakurai et al., 2007).

Three studies compared surgical resection with watchful waiting in patients with NF-pNETs. Triponez et al. compared surgical resection (n=15, follow-up 6.7 years) with watchful waiting (n=50, follow-up 3.3 years) in patients with NF-pNETs 2cm (Triponez et al., 2006b). This study has a high risk of bias. There was no significant difference in progression of disease and deaths between the two groups. Overall life expectancy in patients with NF-pNET < 2cm was not different than that of 229 MEN1 patients in the registry without any dpNET (P = 0.33) (Triponez et al., 2006b).

Partelli et al. compared surgical resection with watchful waiting in n=60 patients with NF-pNETs < 2cm, with patients analyzed as intention to treat (Partelli et al., 2016). Risk of bias was moderate. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as development of metastases, growth of existing tumors, or development of new tumors. The development of new metastases (P = 1), pNET-related death (P = 0.9), and tumor enlargement during follow-up (P = 0.2) were not different between watchful waiting (median follow-up 9.1 years) and surgery (median follow-up 10.6 years). Overall survival of the entire cohort was 98% at 5 and 10 years, and PFS at 5, 10, and 15 years was 63%, 39%, and 10%, respectively. There was no statistical difference between watchful waiting and surgical intervention (P = 0.2) (Partelli et al., 2016).

The study by Nell et al. (low risk of bias) comparing surgical resection of NF-pNETs with watchful waiting from the DutchMEN study group (DMSG), had the largest sample size (n=152) (Nell et al., 2018). Fifty-three patients underwent surgery with a median follow-up of 4.5 years, and 99 underwent watchful waiting for a median follow-up of 7.2 years. Using a propensity score analysis to correct for differences between both groups, surgery for NF-pNETs was found not to be associated with a significantly lower risk of liver metastases or death [adjusted HR = 0.73 (0.25–2.11)]. Adjusted HR after stratification by size were < 2cm = 2.04 (0.31–13.59) and 2–3cm = 1.38 (0.09–20.31). The subgroup > 3cm was too small for time varying analysis, however 5/6 (83%) patients with NF-pNETs > 3cm managed by watchful waiting developed liver metastases or died compared with 6/16 (38%) patients who underwent surgical intervention (Nell et al., 2018).

Although there is overall a significant risk of bias, results from studies looking at prognostic value of size compared with the results of studies that compare watchful waiting with surgical resection based on size-criteria show that risk of metastases and (disease-related) death is low in MEN1-related pNETs <2 cm.

Prognostic value of tissue-based markers

Four studies were included that investigated the prognostic value of tissue-based markers, in all studies these were assessed by pathological examination of surgically resected MEN1-related pNETs (Conemans et al., 2017a, Cejas et al., 2019, Conemans et al., 2018a, Conemans et al., 2018b) (Table 2). The studies by Conemans et al. had a low risk of bias, by Cejas et al. moderate (Table 1). All of these studies report on the same MEN1 patient population (from the DMSG). Development of liver metastases was the primary endpoint and occurred in 17%, mostly metachronous.

When assessing the prognostic value of the World Health Organization (WHO) grade in MEN1-related NF-pNETs, higher WHO grade based on mitotic index was associated with a higher risk of liver metastases in tumors > 2cm (5-year liver metastases free survival 90% for grade 1 tumors and 40% for grade 2 tumors; log rank p=0.000). WHO grade based on Ki-67 labeling index (LI) or combined mitotic index and Ki-67 LI was not associated with liver metastases (Conemans et al., 2017a).

Cejas et al. investigated the prognostic value of NF-pNET subsets based on their resemblance to islet alpha and beta cells (Cejas et al., 2019). They confirmed that A (resembling alpha cells) and B (resembling beta cells) type tumors expressed transcription factors (TFs) ARX and PDX1, respectively. (These TFs can be assessed on tumor specimen by immunohistochemistry (IHC).) They subsequently assessed the prognostic value of tumor type (ARX+, PDX1+, double positive (DP) or double negative (DN)) and Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT) for the occurrence of distant relapses in resected NF-pNETs. They found that ARX and PDX1 IHC status significantly correlated with occurrence of liver metastases. Liver metastases were only seen in ARX+ or DN cases, not PDX1+ or DP cases. When comparing ARX+ with PDX1+ cases, HR for relapse was 7.09 (95% CI 1.72–42.86) for ARX+ cases. ALT positivity was only seen in ARX+ or DN tumors but not in PDX1+/DN tumors. ALT positivity significantly correlated with relapse rate.

Although the studies examining expression of p27Kip1/p18Inkc4c (Conemans et al., 2018b) and DNA methylation (Conemans et al., 2018a) in MEN1-related pNETs did not have a primary prognostic aim, they did include prognostic data. No significant association between p27Kip1 and p18Inkc4c expression and clinical and pathological characteristics was seen (Conemans et al., 2018b). NF-pNETs with synchronous or metachronous liver metastases had a higher (1,036 vs. 869, P = 0.013) cumulative methylation index (defined as the sum of methylation percentages of the promotors of the 56 investigated tumor suppression genes) (Conemans et al., 2018a).

Based on these studies, we conclude that in patients with MEN1 undergoing resection of an NF-pNET, grade by mitotic index can be used to identify patients at higher risk for future development of liver metastases. In addition, ARX/PDX1 IHC and ALT status seem to be potential powerful prognostic indicators. Additional prospective studies must follow to determine feasibility in the clinical setting. Assessing p27Kip1 and p18Inkc4c alone to determine the future risk of developing liver metastases is not useful. DNA methylation status might be of interest as a prognostic biomarker, however additional data is necessary.

Prognostic factors associated with tumor growth

Two studies aimed to assess growth rate/natural course of NF-pNETs <2 cm in patients with MEN1 (Table 2) (D’Souza S et al., 2014, Pieterman et al., 2017). In the first study, a population-based study with low risk of bias, the natural course of 115 NF-pNETs < 2cm from 99 patients is described (Pieterman et al., 2017), with a median follow-up of 5 years after the first imaging. Indication for watchful waiting or intervention was determined by the treating physician/team. Tumor growth was assessed on Magnetic Resonance Imaging/ Computed Tomography (MRI/CT) using linear mixed-model analysis and genotype, age, gender, hypergastrinemia, existing versus new tumor, and baseline tumor size were all assessed for influence on growth rate. Growth rate was 0.4 mm/y. Thirty percent of the tumors was progressive (growth rate 1.6 mm/y) while 70% remained stable without identifiable growth. Genotype was a significant modifier of growth in the subgroup of progressive tumors, with tumors with germline missense mutations demonstrating faster growth. Other factors did not influence growth rate in the subgroup of progressive tumors, and none of the factors distinguished between progressive and stable tumors. D’souza et al. (moderate risk of bias) reported the natural course of 18 NF-pNETs <2cm in 11 patients with MEN1 assessed by Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) (D’Souza S et al., 2014) during a mean follow-up of 6.5 year. They report significantly different growth rates for existing lesions (1.32 mm/y) compared to newly diagnosed lesions (3 mm/year). We suspect this finding to be caused by selection bias and do not consider this an important modifier of growth.

Discussion

This systematic review summarizes prognostic factors in MEN1-related NF-pNETs, based on 13 studies including n=370 unique patients since the same patients were described in multiple studies. Results show that tumor size (using 2 cm as cut-off) and WHO grade are prognostic factors that can be used in clinical practice, while ARX/PDX1 IHC status and ALT are potential novel prognostic biomarkers.

Prognostic data from studies in MEN1-related pNETs for which data cannot be separately extracted for NF-pNET can be used as supporting evidence and to identify prognostic factors that might be applied to all NF-pNETs as well (Overview provided in Supplemental Table 3). These studies corroborate the increased risk of distant metastases in pNETs >2 cm (Vinault et al., 2018). In addition, they show that despite numerous efforts, no definitive genotype-phenotype correlation has been identified in MEN1-related pNETs mainly due to lack of validation of reported associations, and therefore we currently do not recommend basing management decisions on specific genotype (Bartsch et al., 2014, Christakis et al., 2018, Giudici et al., 2017, Thevenon et al., 2013). A biological reason for the lack of validated genotype-phenotype correlations may be that menin does not have intrinsic enzymatic activity and is involved in multiple cellular processes (most importantly epigenetic regulation of gene transcription) through interaction with other proteins (Iyer and Agarwal, 2018). It might therefore also be of value to investigate if variants in genes coding for menin-interacting proteins might modify the phenotype, such as been suggested in a publication showing that patients with CDKN1B V109G polymorphism had more aggressive tumors (Circelli et al., 2015). For patients with multifocal pNETs imaging-based prognostication is appealing as it is non-invasive and can be repeated over time. Two small retrospective studies in MEN1 indicate that FDG-avidity (FGD-avidity predicted more aggressive disease) and SUVmax (lower SUVmax associated with decreased median PFS) might be of prognostic value (Kornaczewski Jackson et al., 2017, Lastoria et al., 2016). It is interesting to note that one study observed higher estrogen exposure to be associated with smaller pNETs (Qiu et al., 2017). Although this study had significant risk of bias because only a small selected subgroup of the patients could be used in this analysis, this certainly is an area of interest, given that menin is known to interact with the estrogen receptor (Dreijerink et al., 2006), and that several studies show male sex to be an adverse prognostic factor (Conemans et al., 2017b, Vinault et al., 2018).

As MEN1 is also one of the most important driver genes in sporadic pNETs (Jiao et al., 2011, Scarpa et al., 2017), evidence gained from sporadic pNETs might be applied to MEN1-related pNETs as well. Indeed, cumulative methylation index was found not to be statistically different between MEN1-related and sporadic NF-PNETs (Conemans et al., 2018a), the prognostic value of ARX/PDX1 IHC was found to be similar in MEN1-related and sporadic nf-PNETs (Cejas et al., 2019) and mRNA expression analysis has revealed that a subgroup of sporadic pNETs clustered with MEN1-related pNETs, while others clustered alone (Keutgen et al., 2018). All this lends credence to the fact that at least a subgroup of sporadic (NF)-pNETs - those with somatic MEN1 mutations? - is biologically comparable to MEN1. However, apart from the fact that over 60% of sporadic pNETs are not MEN1-mutated, there are important clinical differences that can influence use and value of prognostic factors. Patients with MEN1 are younger at diagnosis, have multifocal tumors, are diagnosed in an earlier stage due to surveillance and often have other concomitant primary neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine tumors. This necessitates validation of evidence from sporadic pNETs in MEN1 before this can be applied in practice. Table 3 provides a comparison of the prognostic data in sporadic and MEN1-related (NF-)pNETs.

Table 3:

Overview of Prognostic Factors with Evidence in both MEN1-related and Sporadic NF-pNET

| Prognostic factor | Evidence in MEN1-related NF-pNETs | Evidence in sporadic NF-pNETs |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor size | Tumor size correlates with risk of metastases, (Sakurai et al., 2007, Triponez et al., 2006a) with low risk for tumors < 2cm (Nell et al., 2018, Partelli et al., 2016, Triponez et al., 2006b, Conemans et al., 2017)a. | Increased tumor size associated with reduced DFS, with < 2 cm a good cutoff for observation (Lee et al., 2019). Low risk of metastases when observing tumors < 2cm (Partelli et al., 2017, Partelli et al., 2019), especially when no bile duct involvement (Sallinen et al., 2018). |

| WHO grade / Ki-67 | In tumors > 2cm, higher WHO grade as defined by mitotic index associated with a higher risk of LM (Conemans et al., 2017)a. Tumor grade based on Ki-67 or combination of Ki-67 and mitotic index not associated with development of LM (Conemans et al., 2017)a. |

Higher WHO grade/ Ki-67 labeling index is one of the most prominent factors associated with worse DFS, DSS and OS (Lee et al., 2019). |

| DAXX/ATRX and/or ALT | ALT positivity associated with distant relapses (Cejas et al., 2019). | ALT and loss of DAXX/ATRX are associated with decreased DFS (Chou et al., 2018, Cives et al., 2019, Kim et al., 2017, Marinoni et al., 2014, Pipinikas et al., 2015, Roy et al., 2018, Singhi et al., 2017), ATRX loss is associated with poorer OS (Chou et al., 2018) and DAXX/ATRX loss is associated with shorted DSS (Marinoni et al., 2014). ALT associated with distant metastases in NF-pNETs <3cm (Pea et al., 2018). In metastatic pNETs, ALT and DAXX/ATRX loss associated with improved OS (Dogeas et al., 2014, Jiao et al., 2011, Kim et al., 2017). |

| PDX1 / ARX | Distant metastases only seen in ARX positive or ARX and PDX1 negative tumors (Cejas et al., 2019). | Distant metastases almost exclusively seen in ARX positive or ARX and PDX1 negative tumors (Cejas et al., 2019). |

| Tumor growth | Growth rate of NF-pNETs <2 cm 0.4–3 mm/year (D’Souza S et al., 2014, Pieterman et al., 2017). No clinical factor distinguishes between progressive and stable tumors. In progressive tumors, tumors with germline missense mutation grow faster (Pieterman et al., 2017). |

Most sporadic NF-pNETs <2cm do not exhibit meaningful growth during observation (Choi et al., 2018, Sallinen et al., 2017). Hypervascularity was found to be associated with less growth (Choi et al., 2018). Growth was found to be associated with grade 2 or grade 3 tumors (Jung et al., 2015). |

| Imaging-related characteristics | Lower SUVmax on 68Gallium-dotatate PET associated with decreased PFS in pNET (Lastoria et al., 2016). FDG-avidity of pNET associated with more aggressive disease (Ki-67 ≥ 5%) (Kornaczewski Jackson et al., 2017). |

Imaging factors associated with worse DFS/OS include: tumoral hypo-enhancement/vascularity, presence of main pancreatic duct involvement, presence of irregular tumor margins (Lee et al., 2019). Higher uptake on 18F-FDG PET correlates with poorer OS and with advancing classification/grade (Rinzivillo et al., 2018). |

Abbreviations: ALT alternative lengthening of telomeres DFS disease-free survival DSS disease-specific survival FDG fluorodeoxyglucose LM Liver metastases NF non-functioning OS overall survival PD-1 programmed cell death protein 1 PET positron emission tomography PFS progression-free survival pNET pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors SUV standardized uptake value TAM tumor-associated macrophages WHO World Health Organization

With regards to tumor size in sporadic NF-pNETs, overall, increased tumor size is associated with reduced DFS, with < 2cm a good cutoff for watchful waiting (Lee et al., 2019). A recent large single center retrospective study and a Systematic Review in 540 sporadic NF-pNET revealed low risk of metastases when managing tumors < 2cm with watchful waiting (Partelli et al., 2017, Partelli et al., 2019). This is reinforced in a multi-institutional retrospective study of 210 resected NF-pNETs with tumors ≤ 2cm. They report a high surgical morbidity rate of 14.3% (n = 30), and found the presence of biliary or pancreatic duct dilatation, and WHO grade 2–3 to be independently associated with recurrence. Thus, they advocate surgery for NF-pNET <2cm with those features, and a wait-and-see policy in the remaining patients (Sallinen et al., 2017). This is in line with evidence from MEN1-related NF-pNETs.

The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS) consensus states that, based on a review of retrospective studies, tumors <1cm have low risk of metastases and should be followed by watchful waiting, however, that tumors between 1–2cm should be managed in an individualized manner (according to risk factors) (Howe et al., 2020).

As in MEN1-related NF-pNETs, retrospective studies of sporadic NF-pNETs < 2 cm managed with a watchful waiting strategy show that most do not exhibit meaningful growth during follow-up and no distant metastases were observed (Choi et al., 2018, Sallinen et al., 2017). Median follow-up was less than five years in all of these studies. One study did not identify predictors of tumor growth among patient (sex, age) or tumor characteristics (localization, cystic, size) (Gaujoux et al., 2013), while another study found hypervascularity to be associated with less risk of growth as other factors (sex, age, size, location, other tumor characteristics) were not associated with growth (Choi et al., 2018). One study found growth to be associated with grade 2 or grade 3 tumors (Jung et al., 2015). As in MEN1, exact relation between tumor growth rate and outcome in localized disease is unknown in sporadic NF-pNETs as no data on this subject is available. Time from diagnosis to surgical intervention might indicate whether a tumor is growing rapidly, however no data are available on this subject in MEN1.

Overall, in sporadic pNETs, WHO grade and Ki-67 are one of the most important prognostic factors for Overall Survival (OS) and Disease Specific Survival (DSS) as well as Recurrence Free Survival (RFS), OS and DSS after surgical resection (Lee et al., 2019). Recent large retrospective multi-center studies focusing specifically on NF-pNETs have confirmed the important prognostic value of Ki-67 and WHO grade on recurrence (defined as either local or distant recurrence) (Genc et al., 2018a, Zaidi et al., 2019), also in NF-pNET <2cm (Sallinen et al., 2018). Although most studies follow the cut-off for Ki-67 as set by the WHO (3%), some advocate for 5% as cut-off between G1 and G2 tumors (Lopez-Aguiar et al., 2018). Other studies (also including functioning tumors) show that subdividing low-grade Ki-67 into <1% vs 1–2.99% might improve prognostic classification (Lopez-Aguiar et al., 2018) or even that Ki-67 has a more linear relation with recurrence and should be viewed more as a continuous than categorical variable (Gao et al., 2018). A different cut-off might improve prognostic value of Ki-67 in MEN1-related NF-pNETs, and may have been the reason no association with outcome could be identified by Conemans et al (Conemans et al., 2017a).

Looking at histopathological prognostic markers in sporadic pNETs, a systematic review not surprisingly found lymph node metastases to be strongly associated with increased risk of recurrence and OS (Lee et al., 2019, Tao et al., 2017). This factor has been widely studied in resections for sporadic pNETs as well as in sporadic gastrinoma / functioning duodenal-pancreatic NETs. There are unfortunately no studies specifically looking at lymph node dissections or lymph node ratio as prognostic factors for outcome in NF-pNETs in MEN1. In MEN1, functioning and NF-pNETs often co-exist and it is difficult to attribute lymph node metastases to their primary tumor, which poses a challenge to prognostic research. Also, prognostic value of lymph node metastases from gastrinoma might be different from that in NF-pNETs. Additionally, presence of perineural or vascular invasion are predictors of tumor recurrence or metastases (Ge et al., 2017, Lee et al., 2019). Invasion into adjacent organs represents a high risk of recurrence (HR of 1.65 (95% CI, 1.03–2.65; P = 0.038) (Merath et al., 2018) and R1 resections are associated with shorter DFS (Lee et al., 2019).

Several retrospective cohort studies have assessed the prognostic value of DAXX/ATRX loss and/or ALT positivity in sporadic surgically resected pNETs (nonfunctioning 75–100%) (Marinoni et al., 2014, Dogeas et al., 2014, Kim et al., 2017, Jiao et al., 2011, Pipinikas et al., 2015, Singhi et al., 2017, Park et al., 2017, Chou et al., 2018, Pea et al., 2018, Roy et al., 2018, Uemura et al., 2019, Cives et al., 2019). All but one study (Park et al., 2017) found that ALT and/or DAXX/ATRX loss (IHC) was associated with decreased relapse-, recurrence- or progression-free survival (Chou et al., 2018, Cives et al., 2019, Kim et al., 2017, Marinoni et al., 2014, Pipinikas et al., 2015, Roy et al., 2018, Singhi et al., 2017). One study (Chou et al., 2018) also found ATRX loss to be associated with poorer OS and in another study (Marinoni et al., 2014) DAXX/ATRX loss was associated with shorter DSS. In small (<3cm) NF-pNETs ALT was found to be associated with the occurrence of distant metastases (Pea et al., 2018). Intriguingly, in metastatic pNETs, ALT and DAXX/ATRX loss have found to be associated with improved OS (Dogeas et al., 2014, Jiao et al., 2011, Kim et al., 2017). As in MEN1, in sporadic NF-pNETs expression of TFs ARX and PDX1 as surrogate markers for alpha or beta cell resemblance, was shown to be associated with metastases (Cejas et al., 2019). Importantly, distant metastases almost exclusively occurred in tumors that were ARX+ or negative for both transcription factors.

As in MEN1-related NF-pNETS, hypermethylation is also a frequent event in sporadic NF-pNETs (Conemans et al., 2018a, Tirosh et al., 2019), although methylation patterns are different between MEN1-related and sporadic NF-pNETs (Tirosh et al., 2019). No data exist regarding prognostic value of DNA methylation patterns in sporadic NF-pNETs. Further study of methylation patterns and specific genes targeted may provide not only novel therapeutic targets but might also lead to novel tissue-based prognostic biomarkers.

Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) can provide prognostic tissue-based information prior to intervention. Ki-67 can be determined pre-operatively on FNAC specimen although this has only been assessed specifically for NF-pNETs in two small cohort studies. In the first prospective cohort study of n=30, concordance between EUS FNAC grade and final post-surgical grade was 83%. In the second retrospective cohort study (n=36), concordance was 73%, with discordant results particularly in intermediate grade tumors (5/8). Other studies have also reported the inaccuracy of cytology grading for intermediate or grade 2 tumors (Boutsen et al., 2018, Hackeng et al., 2019). Importantly, ALT (by telomere FISH) and DAXX/ATRX and ARX (by IHC) can also be determined on FNAC specimen (Hackeng et al., 2019, VandenBussche et al., 2017). No data are available on the prognostic value of EUS-FNAC based markers in patients who are followed with a watchful waiting strategy. Although EUS-FNAC-based prognostication can be valuable to inform management decisions prior to intervention, challenges in MEN1 arise due to multiplicity of tumors and need for repeated assessment.

In recent years more data has become available on prognostic value of imaging-related factors beyond classic stage-associated information. Factors associated with worse DFS/OS in sporadic pNETs include tumoral hypo-enhancement/vascularity, the presence of main pancreatic duct involvement, as well as the presence of irregular tumor margins (Lee et al., 2019). Additionally, on functional imaging, higher uptake/ SUVmax on 18F-FDG PET correlates with a poorer OS and correlates closely with advancing classification/grade in sporadic pNETs (Rinzivillo et al., 2018), as does low SUVmax on 68-Ga-DOTATATE scans (Lee and Kim, 2019, Lee et al., 2019). This complements evidence regarding prognostic value of functional imaging in MEN1-related NF-pNETs, as discussed above (Kornaczewski Jackson et al., 2017, Lastoria et al., 2016).

Several novel biomarkers classes are currently under investigation in sporadic pNETs, for none of which data are available in MEN1-related pNETs.

Micro-RNAs are one of these novel biomarker classes, and their role in NETs has been recently reviewed (Malczewska et al., 2018). In tissue-based retrospective studies (comprising of both nonfunctioning and functioning pNETs, >90% sporadic) miR-21 was found to be associated with metastasized disease (Roldo et al., 2006) and worse PFS/OS (Grolmusz et al., 2018), miR-210 was found to be associated with metastatic disease (Thorns et al., 2014), miR-196a with decreased DFS/OS (Lee et al., 2015) and miR-3653 with development of metastatic disease following surgical resection (Gill et al., 2019).

The recently developed NETest (Wren Laboratories, Branford, CT, USA), a multi-transcript RNA-based molecular signature for PCR-based blood analysis, has shown promising results in the detection of sporadic NETs (Modlin et al., 2014, Modlin et al., 2013). Genç et al. demonstrated that this multigene blood test could effectively detect pNET recurrence after surgical resection (test performed after recurrence had occurred in a cohort of NF (83%) and functioning (17%) pNETs) (Genc et al., 2018b). A recent meta-analysis shows an accuracy of 90.2–93.6% as a marker of natural history of NET (not pNET or NF-pNET specific) (Oberg et al., 2020). Therefore, the NETest seems an accurate biomarker suitable for clinical use in NET disease management (Oberg et al., 2020). However, large validation studies with long-term follow-up are now needed. Given the aforementioned characteristics of MEN1, such as multiple co-occurring NETs, this applies especially to patients with MEN1.

There is very few data on circulating tumors cells (CTC) in pNETs. Work by Khan et al. has shown that CTC can be detected in 21% of metastatic pNET and that the presence of CTC is correlated with a worse prognosis, however this was determined in a cohort of metastatic NETs of all sites, not solely pancreatic NETs (Khan et al., 2013, Khan et al., 2011). Given the low mutational burden in pNET, use of circulating or cell-free tumor DNA (ctDNA) as prognostic biomarker will be challenging. One study demonstrated ctDNA could be identified in patients with metastatic pNET, however no prognostic data are available to date (Boons et al., 2018). A few retrospective studies have investigated the immune environment of pNETs (most nonfunctioning but also including functioning tumors) and found a correlation between tumor-associated macrophages and adverse outcome (Cai et al., 2019, Pyonteck et al., 2012, Wei et al., 2014). Also in two other studies PD-1 expression by tumor mononuclear cells was associated with metastases (Sampedro-Nunez et al., 2018) and PD-1 expression by intra-epithelial T-cells was associated with worse outcome (Takahashi et al., 2018). Another small study did not find a correlation between tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and postoperative hepatic recurrence (Sato et al., 2014). Markers of inflammatory response in peripheral blood have also been investigated for their prognostic value and a higher neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is found to be associated with decreased OS and PFS (Panni et al., 2019, Zhou et al., 2018).

Our systematic review underscores the paucity of dedicated prognostic research in MEN1-related NF-pNETs. There are only very few well described non-selected cohorts with sufficient follow-up data available leading to the same patients described in multiple studies. To enable meaningful prognostic research in MEN1-related (NF)-pNETs collaboration between institutions and research groups and standardized collection of data and biospecimen is essential. This allows for sufficient sample size for predictive modeling as well as providing cohorts for validation of findings. To advance knowledge and make optimal use of data generated in sporadic NF-pNETs while still appropriately validating in MEN1, future prognostic studies might include germline MEN1 mutated, somatic MEN1 mutated and wild-type tumors and perform stratified analysis to identify differential performance of prognostic factors. In addition novel prognostic factors identified in sporadic NF-pNETs can be validated in MEN1 cohorts. In MEN1, the most actionable time-point for prognostic information is at diagnosis and during surveillance of an NF-pNET because this informs the decision when to intervene. Due to increasing incidental diagnosis, this time-point becomes more important in sporadic NF-pNETs as well, and knowledge from MEN1 might be extrapolated to sporadic NF-pNETs after proper validation. As there is no adjuvant therapy available for MEN1-related NF-pNETs, prognostic information at the time of surgical resection currently only informs on surveillance strategies. Patients identified as high risk may be good candidates for adjuvant therapy trials or biomarker discovery. It is important to realize when designing prognostic research, that in patients with MEN1, pancreatic “recurrence” after resection represents novel primaries and should be recognized as such.

This is the first review systematically summarizing the literature on prognostic factors in MEN1-related NF-pNETs. Due to stringent inclusion criteria as well as limiting inclusion to papers published from 2001 onwards, we ensure applicability of the results to present-day patients with MEN1-related pNETs. A number of limitations should be discussed. We were not able to conduct a meta-analysis due to study heterogeneity. With only 370 unique patients, results are based on a small population. Follow-up in most studies did not exceeded 10 years, which is short given the indolent nature of tumors diagnosed in young patients. Although we only included studies published from 2001 onwards, inclusion periods in the included studies were long also included patients evaluated before 2001, given their retrospective nature.

Conclusion

Based on our systematic review of prognostic factors in MEN1-related NF-pNETs, combined with evidence from sporadic NF-pNETs and MEN1-related pNETs in general, we conclude that the most important prognostic factors to be used in clinical decision making in MEN1-related NF-pNETs are currently tumor size and grade. Based on the available evidence, NF-pNETs <2 cm may be managed with watchful waiting, while surgical resection is advised for NF-pNETs ≥ 2cm. Grade 2 NF-pNETs should be considered high risk. Management decisions should be made in a multi-disciplinary team and patients with MEN1 should be treated by knowledgeable experts. We also conclude that currently available prognostic factors are insufficient for precise individual prognostication and have room for improvement. In all likelihood further stratification of risk will come from genetic and molecular factors refining or perhaps even replacing currently used clinical risk assessment. The most promising and MEN1-relevant avenues of prognostic research are multi-analyte circulating biomarkers, tissue based molecular factors and imaging-based prognostication. Multi-institutional collaboration between clinical, translation and basic scientists with uniform data and biospecimen collection in prospective cohorts should advance the field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alicia A. Livinski from the National Institutes of Health Library for her assistance with development of the search strategy, literature searching, citation management, and full-text retrieval.

We appreciate the assistance of Sunita K. Agarwal and Ronald de Krijger in the development of the prognostic factor measurement criteria for the modified QUIPS tool.

Funding

The study was funded in part by the intramural research program of the National Cancer Institute (Sadowski SM).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- BARTSCH DK, FENDRICH V, LANGER P, CELIK I, KANN PH & ROTHMUND M 2005. Outcome of duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Annals of surgery, 242, 757–64, discussion 764–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARTSCH DK, SLATER EP, ALBERS M, KNOOP R, CHALOUPKA B, LOPEZ CL, FENDRICH V, KANN PH & WALDMANN J 2014. Higher risk of aggressive pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in MEN1 patients with MEN1 mutations affecting the CHES1 interacting MENIN domain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 99, E2387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOONS G, VANDAMME T, PEETERS M, BEYENS M, DRIESSEN A, JANSSENS K, ZWAENEPOEL K, ROEYEN G, VAN CAMP G & OP DE BEECK K 2018. Cell-Free DNA From Metastatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Patients Contains Tumor-Specific Mutations and Copy Number Variations. Front Oncol, 8, 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOUTSEN L, JOURET-MOURIN A, BORBATH I, VAN MAANEN A & WEYNAND B 2018. Accuracy of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumour Grading by Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration: Analysis of a Large Cohort and Perspectives for Improvement. Neuroendocrinology, 106, 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAI L, MICHELAKOS T, DESHPANDE V, ARORA KS, YAMADA T, TING DT, TAYLOR MS, CASTILLO CF, WARSHAW AL, LILLEMOE KD, et al. 2019. Role of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in the Clinical Course of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PanNETs). Clin Cancer Res, 25, 2644–2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CEJAS P, DRIER Y, DREIJERINK KMA, BROSENS LAA, DESHPANDE V, EPSTEIN CB, CONEMANS EB, MORSINK FHM, GRAHAM MK, VALK GD, et al. 2019. Enhancer signatures stratify and predict outcomes of non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Nat Med, 25, 1260–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANDRASEKHARAPPA SC, GURU S, MANICKAM P, OLUFEMI S, COLLINS F, EMMERT-BUCK M, DEBELENKO L, ZHUANG Z, LUBENSKY I, LIOTTA L, et al. 1997. Positional Cloning of the Gene for Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia-Type 1 Science, 276, 404–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOI JH, CHOI YH, KANG J, PAIK WH, LEE SH, RYU JK & KIM YT 2018. Natural History of Small Pancreatic Lesions Suspected to Be Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas, 47, 1357–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOU A, ITCHINS M, DE REUVER PR, ARENA J, CLARKSON A, SHEEN A, SIOSON L, CHEUNG V, PERREN A, NAHM C, et al. 2018. ATRX loss is an independent predictor of poor survival in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Hum Pathol, 82, 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHRISTAKIS I, QIU W, HYDE SM, COTE GJ, GRUBBS EG, PERRIER ND & LEE JE 2018. Genotype-phenotype pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor relationship in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 patients: A 23-year experience at a single institution. Surgery, 163, 212–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIRCELLI L, RAMUNDO V, MAROTTA V, SCIAMMARELLA C, MARCIELLO F, DEL PRETE M, SABATINO L, PASQUALI D, IZZO F, SCALA S, et al. 2015. Prognostic role of the CDNK1B V109G polymorphism in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. J Cell Mol Med, 19, 1735–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIVES M, PARTELLI S, PALMIROTTA R, LOVERO D, MANDRIANI B, QUARESMINI D, PELLE E, ANDREASI V, CASTELLI P, STROSBERG J, et al. 2019. DAXX mutations as potential genomic markers of malignant evolution in small nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Sci Rep, 9, 18614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONEMANS EB, BROSENS LAA, RAICU-IONITA GM, PIETERMAN CRC, DE HERDER WW, DEKKERS OM, HERMUS AR, VAN DER HORST-SCHRIVERS AN, BISSCHOP PH, HAVEKES B, et al. 2017a. Prognostic value of WHO grade in pancreatic neuro-endocrine tumors in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 1: Results from the DutchMEN1 Study Group. Pancreatology, 17, 766–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONEMANS EB, LODEWIJK L, MOELANS CB, OFFERHAUS GJA, PIETERMAN CRC, MORSINK FH, DEKKERS OM, DE HERDER WW, HERMUS AR, VAN DER HORST-SCHRIVERS AN, et al. 2018a. DNA methylation profiling in MEN1-related pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors reveals a potential epigenetic target for treatment. Eur J Endocrinol, 179, 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONEMANS EB, NELL S, PIETERMAN CRC, DE HERDER WW, DEKKERS OM, HERMUS AR, VAN DER HORST-SCHRIVERS AN, BISSCHOP PH, HAVEKES B, DRENT ML, et al. 2017b. Prognostic factors for survival of MEN1 patients with duodenopancreatic tumors metastatic to the liver: results from the DMSG. Endocr Pract, 23, 641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONEMANS EB, RAICU-IONITA GM, PIETERMAN CRC, DREIJERINK KMA, DEKKERS OM, HERMUS AR, DE HERDER WW, DRENT ML, VAN DER HORST-SCHRIVERS ANA, HAVEKES B, et al. 2018b. Expression of p27(Kip1) and p18(Ink4c) in human multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1-related pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Endocrinol Invest, 41, 655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’SOUZA S L, ELMUNZER BJ & SCHEIMAN JM 2014. Long-term follow-up of asymptomatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type I syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol, 48, 458–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVI MV, BONINSEGNA L, DALLE CARBONARE L, TOAIARI M, CAPELLI P, SCARPA A, FRANCIA G & FALCONI M 2011. Presentation and outcome of pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome. Neuroendocrinology, 94, 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE LAAT JM, VAN DER LUIJT RB, PIETERMAN CR, OOSTVEEN MP, HERMUS AR, DEKKERS OM, DE HERDER WW, VAN DER HORST-SCHRIVERS AN, DRENT ML, BISSCHOP PH, et al. 2016. MEN1 redefined, a clinical comparison of mutation-positive and mutation-negative patients. BMC Med, 14, 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOGEAS E, KARAGKOUNIS G, HEAPHY CM, HIROSE K, PAWLIK TM, WOLFGANG CL, MEEKER A, HRUBAN RH, CAMERON JL & CHOTI MA 2014. Alternative lengthening of telomeres predicts site of origin in neuroendocrine tumor liver metastases. J Am Coll Surg, 218, 628–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DREIJERINK KMA, MULDER KW, WINKLER GS, HÖPPENER JWM, LIPS CJM & TIMMERS HTM 2006. Menin links estrogen receptor activation to histone H3K4 trimethylation. Cancer research, 66, 4929–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO H, LIU L, WANG W, XU H, JIN K, WU C, QI Z, ZHANG S, LIU C, XU J, et al. 2018. Novel recurrence risk stratification of resected pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Cancer Lett, 412, 188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAUJOUX S, PARTELLI S, MAIRE F, D’ONOFRIO M, LARROQUE B, TAMBURRINO D, SAUVANET A, FALCONI M & RUSZNIEWSKI P 2013. Observational study of natural history of small sporadic nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 98, 4784–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GE W, ZHOU D, XU S, WANG W & ZHENG S 2017. Surveillance and comparison of surgical prognosis for asymptomatic and symptomatic non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Surg, 39, 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GENC CG, JILESEN AP, PARTELLI S, FALCONI M, MUFFATTI F, VAN KEMENADE FJ, VAN EEDEN S, VERHEIJ J, VAN DIEREN S, VAN EIJCK CHJ, et al. 2018a. A New Scoring System to Predict Recurrent Disease in Grade 1 and 2 Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Ann Surg, 267, 1148–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GENC CG, JILESEN APJ, NIEVEEN VAN DIJKUM EJM, KLUMPEN HJ, VAN EIJCK CHJ, DROZDOV I, MALCZEWSKA A, KIDD M & MODLIN I 2018b. Measurement of circulating transcript levels (NETest) to detect disease recurrence and improve follow-up after curative surgical resection of well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Surg Oncol, 118, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILL P, KIM E, CHUA TC, CLIFTON-BLIGH RJ, NAHM CB, MITTAL A, GILL AJ & SAMRA JS 2019. MiRNA-3653 Is a Potential Tissue Biomarker for Increased Metastatic Risk in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours. Endocr Pathol, 30, 128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIUDICI F, CAVALLI T, GIUSTI F, GRONCHI G, BATIGNANI G, TONELLI F & BRANDI ML 2017. Natural History of MEN1 GEP-NET: Single-Center Experience After a Long Follow-Up. World J Surg, 41, 2312–2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONCALVES TD, TOLEDO RA, SEKIYA T, MATUGUMA SE, MALUF FILHO F, ROCHA MS, SIQUEIRA SA, GLEZER A, BRONSTEIN MD, PEREIRA MA, et al. 2014. Penetrance of functioning and nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 in the second decade of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 99, E89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOUDET P, DALAC A, LE BRAS M, CARDOT-BAUTERS C, NICCOLI P, LEVY-BOHBOT N, DU BOULLAY H, BERTAGNA X, RUSZNIEWSKI P, BORSON-CHAZOT F, et al. 2015. MEN1 disease occurring before 21 years old: a 160-patient cohort study from the Groupe d’etude des Tumeurs Endocrines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 100, 1568–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOUDET P, MURAT A, BINQUET C, CARDOT-BAUTERS C, COSTA A, RUSZNIEWSKI P, NICCOLI P, MENEGAUX F, CHABRIER G, BORSON-CHAZOT F, et al. 2010. Risk factors and causes of death in MEN1 disease. A GTE (Groupe d’Etude des Tumeurs Endocrines) cohort study among 758 patients. World journal of surgery, 34, 249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROLMUSZ VK, KOVESDI A, BORKS K, IGAZ P & PATOCS A 2018. Prognostic relevance of proliferation-related miRNAs in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Eur J Endocrinol, 179, 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HACKENG WM, MORSINK FHM, MOONS LMG, HEAPHY CM, OFFERHAUS GJA, DREIJERINK KMA & BROSENS LAA 2019. Assessment of ARX expression, a novel biomarker for metastatic risk in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, in endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYDEN JA, COTE P & BOMBARDIER C 2006. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med, 144, 427–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYDEN JA, VAN DER WINDT DA, CARTWRIGHT JL, COTE P & BOMBARDIER C 2013. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med, 158, 280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOWE JR, MERCHANT NB, CONRAD C, KEUTGEN XM, HALLET J, DREBIN JA, MINTER RM, LAIRMORE TC, TSENG JF, ZEH HJ, et al. 2020. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Consensus Paper on the Surgical Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas, 49, 1–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IYER S & AGARWAL SK 2018. Epigenetic regulation in the tumorigenesis of MEN1-associated endocrine cell types. J Mol Endocrinol, 61, R13–r24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIAO Y, SHI C, EDIL BH, DE WILDE RF, KLIMSTRA DS, MAITRA A, SCHULICK RD, TANG LH, WOLFGANG CL, CHOTI MA, et al. 2011. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science, 331, 1199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUNG JG, LEE KT, WOO YS, LEE JK, LEE KH, JANG KT & RHEE JC 2015. Behavior of Small, Asymptomatic, Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (NF-PNETs). Medicine (Baltimore), 94, e983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEUTGEN XM, KUMAR S, GARA SK, BOUFRAQECH M, AGARWAL S, HRUBAN RH, NILUBOL N, QUEZADO M, FINNEY R, CAM M, et al. 2018. Transcriptional alterations in hereditary and sporadic nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors according to genotype. Cancer, 124, 636–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHAN MS, KIRKWOOD A, TSIGANI T, GARCIA-HERNANDEZ J, HARTLEY JA, CAPLIN ME & MEYER T 2013. Circulating tumor cells as prognostic markers in neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol, 31, 365–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHAN S, KRENNING EP, VAN ESSEN M, KAM BL, TEUNISSEN JJ & KWEKKEBOOM DJ 2011. Quality of life in 265 patients with gastroenteropancreatic or bronchial neuroendocrine tumors treated with [177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3]octreotate. J Nucl Med, 52, 1361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM JY, BROSNAN-CASHMAN JA, AN S, KIM SJ, SONG KB, KIM MS, KIM MJ, HWANG DW, MEEKER AK, YU E, et al. 2017. Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres in Primary Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Is Associated with Aggressive Clinical Behavior and Poor Survival. Clin Cancer Res, 23, 1598–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KORNACZEWSKI JACKSON ER, POINTON OP, BOHMER R & BURGESS JR 2017. Utility of FDG-PET Imaging for Risk Stratification of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors in MEN1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 102, 1926–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASTORIA S, MARCIELLO F, FAGGIANO A, ALOJ L, CARACO C, AURILIO M, D’AMBROSIO L, DI GENNARO F, RAMUNDO V, CAMERA L, et al. 2016. Role of (68)Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). Endocrine, 52, 488–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE DY & KIM YI 2019. Prognostic Value of Maximum Standardized Uptake Value in 68Ga-Somatostatin Receptor Positron Emission Tomography for Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Nucl Med, 44, 777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE L, ITO T & JENSEN RT 2019. Prognostic and predictive factors on overall survival and surgical outcomes in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: recent advances and controversies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther, 19, 1029–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE YS, KIM H, KIM HW, LEE JC, PAIK KH, KANG J, KIM J, YOON YS, HAN HS, SOHN I, et al. 2015. High Expression of MicroRNA-196a Indicates Poor Prognosis in Resected Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. Medicine (Baltimore), 94, e2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEMMENS I, VAN DE VEN W, KAS K, ZHANG C, GIRAUD S, WAUTOT V, BUISSON N, DE WITTE K, SALANDRE J, LENOIR G, et al. 1997. Identification of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) gene. Human molecular genetics, 6, 1177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOPEZ-AGUIAR AG, ETHUN CG, POSTLEWAIT LM, ZHELNIN K, KRASINSKAS A, EL-RAYES BF, RUSSELL MC, SARMIENTO JM, KOOBY DA, STALEY CA, et al. 2018. Redefining the Ki-67 Index Stratification for Low-Grade Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Improving Its Prognostic Value for Recurrence of Disease. Ann Surg Oncol, 25, 290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACHENS A, SCHAAF L, KARGES W, FRANK-RAUE K, BARTSCH DK, ROTHMUND M, SCHNEYER U, GORETZKI P, RAUE F & DRALLE H 2007. Age-related penetrance of endocrine tumours in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1): a multicentre study of 258 gene carriers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 67, 613–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALCZEWSKA A, KIDD M, MATAR S, KOS-KUDLA B & MODLIN IM 2018. A Comprehensive Assessment of the Role of miRNAs as Biomarkers in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology, 107, 73–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANOHARAN J, RAUE F, LOPEZ CL, ALBERS MB, BOLLMANN C, FENDRICH V, SLATER EP & BARTSCH DK 2017. Is Routine Screening of Young Asymptomatic MEN1 Patients Necessary? World J Surg, 41, 2026–2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARINONI I, KURRER AS, VASSELLA E, DETTMER M, RUDOLPH T, BANZ V, HUNGER F, PASQUINELLI S, SPEEL EJ & PERREN A 2014. Loss of DAXX and ATRX are associated with chromosome instability and reduced survival of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Gastroenterology, 146, 453–60.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERATH K, BAGANTE F, BEAL EW, LOPEZ-AGUIAR AG, POULTSIDES G, MAKRIS E, ROCHA F, KANJI Z, WEBER S, FISHER A, et al. 2018. Nomogram predicting the risk of recurrence after curative-intent resection of primary non-metastatic gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: An analysis of the U.S. Neuroendocrine Tumor Study Group. J Surg Oncol, 117, 868–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MODLIN IM, DROZDOV I, ALAIMO D, CALLAHAN S, TEIXIERA N, BODEI L & KIDD M 2014. A multianalyte PCR blood test outperforms single analyte ELISAs (chromogranin A, pancreastatin, neurokinin A) for neuroendocrine tumor detection. Endocr Relat Cancer, 21, 615–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MODLIN IM, DROZDOV I & KIDD M 2013. The identification of gut neuroendocrine tumor disease by multiple synchronous transcript analysis in blood. PLoS One, 8, e63364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELL S, BOREL RINKES IH, VERKOOIJEN HM, BONSING BA, VAN EIJCK CH, VAN GOOR H, DE KLEINE RH, KAZEMIER G, NIEVEEN VAN DIJKUM EJ, DEJONG CH, et al. 2016. Early and Late Complications After Surgery For MEN1-related Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Ann Surg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELL S, VERKOOIJEN HM, PIETERMAN CRC, DE HERDER WW, HERMUS AR, DEKKERS OM, VAN DER HORST-SCHRIVERS AN, DRENT ML, BISSCHOP PH, HAVEKES B, et al. 2018. Management of MEN1 Related Nonfunctioning Pancreatic NETs: A Shifting Paradigm: Results From the DutchMEN1 Study Group. Ann Surg, 267, 1155–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OBERG K, CALIFANO A, STROSBERG JR, MA S, PAPE U, BODEI L, KALTSAS G, TOUMPANAKIS C, GOLDENRING JR, FRILLING A, et al. 2020. A meta-analysis of the accuracy of a neuroendocrine tumor mRNA genomic biomarker (NETest) in blood. Ann Oncol, 31, 202–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANNI RZ, LOPEZ-AGUIAR AG, LIU J, POULTSIDES GA, ROCHA FG, HAWKINS WG, STRASBERG SM, TRIKALINOS NA, MAITHEL S & FIELDS RC 2019. Association of preoperative monocyte-to-lymphocyte and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with recurrence-free and overall survival after resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (US-NETSG). J Surg Oncol, 120, 632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK JK, PAIK WH, LEE K, RYU JK, LEE SH & KIM YT 2017. DAXX/ATRX and MEN1 genes are strong prognostic markers in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Oncotarget, 8, 49796–49806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARTELLI S, CIROCCHI R, CRIPPA S, CARDINALI L, FENDRICH V, BARTSCH DK & FALCONI M 2017. Systematic review of active surveillance versus surgical management of asymptomatic small non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Br J Surg, 104, 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARTELLI S, MAZZA M, ANDREASI V, MUFFATTI F, CRIPPA S, TAMBURRINO D & FALCONI M 2019. Management of small asymptomatic nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Limitations to apply guidelines into real life. Surgery, 166, 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARTELLI S, TAMBURRINO D, LOPEZ C, ALBERS M, MILANETTO AC, PASQUALI C, MANZONI M, TOUMPANAKIS C, FUSAI G, BARTSCH D, et al. 2016. Active Surveillance versus Surgery of Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms </=2 cm in MEN1 Patients. Neuroendocrinology, 103, 779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEA A, YU J, MARCHIONNI L, NOE M, LUCHINI C, PULVIRENTI A, DE WILDE RF, BROSENS LA, REZAEE N, JAVED A, et al. 2018. Genetic Analysis of Small Well-differentiated Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Identifies Subgroups With Differing Risks of Liver Metastases. Ann Surg. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIETERMAN CRC, DE LAAT JM, TWISK JWR, VAN LEEUWAARDE RS, DE HERDER WW, DREIJERINK KMA, HERMUS A, DEKKERS OM, VAN DER HORST-SCHRIVERS ANA, DRENT ML, et al. 2017. Long-Term Natural Course of Small Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors in MEN1-Results From the Dutch MEN1 Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 102, 3795–3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIPINIKAS CP, DIBRA H, KARPATHAKIS A, FEBER A, NOVELLI M, OUKRIF D, FUSAI G, VALENTE R, CAPLIN M, MEYER T, et al. 2015. Epigenetic dysregulation and poorer prognosis in DAXX-deficient pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer, 22, L13–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PYONTECK SM, GADEA BB, WANG HW, GOCHEVA V, HUNTER KE, TANG LH & JOYCE JA 2012. Deficiency of the macrophage growth factor CSF-1 disrupts pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor development. Oncogene, 31, 1459–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QIU W, CHRISTAKIS I, STEWART AA, VODOPIVEC DM, SILVA-FIGUEROA A, CHEN H, WOODARD TL, HALPERIN DM, LEE JE, YAO JC, et al. 2017. Is estrogen exposure a protective factor for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours in female patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 1? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 86, 791–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RINZIVILLO M, PARTELLI S, PROSPERI D, CAPURSO G, PIZZICHINI P, IANNICELLI E, MEROLA E, MUFFATTI F, SCOPINARO F, SCHILLACI O, et al. 2018. Clinical Usefulness of (18)F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography in the Diagnostic Algorithm of Advanced Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Oncologist, 23, 186–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROLDO C, MISSIAGLIA E, HAGAN JP, FALCONI M, CAPELLI P, BERSANI S, CALIN GA, VOLINIA S, LIU CG, SCARPA A, et al. 2006. MicroRNA expression abnormalities in pancreatic endocrine and acinar tumors are associated with distinctive pathologic features and clinical behavior. J Clin Oncol, 24, 4677–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROY S, LAFRAMBOISE WA, LIU TC, CAO D, LUVISON A, MILLER C, LYONS MA, O’SULLIVAN RJ, ZUREIKAT AH, HOGG ME, et al. 2018. Loss of Chromatin-Remodeling Proteins and/or CDKN2A Associates With Metastasis of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Reduced Patient Survival Times. Gastroenterology, 154, 2060–2063.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAKURAI A, KATAI M, YAMASHITA K, MORI J, FUKUSHIMA Y & HASHIZUME K 2007. Long-term follow-up of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Endocrine journal, 54, 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALLINEN V, LE LARGE TY, GALEEV S, KOVALENKO Z, TIEFTRUNK E, ARAUJO R, CEYHAN GO & GAUJOUX S 2017. Surveillance strategy for small asymptomatic non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors - a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford), 19, 310–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALLINEN VJ, LE LARGE TYS, TIEFTRUNK E, GALEEV S, KOVALENKO Z, HAUGVIK SP, ANTILA A, FRANKLIN O, MARTINEZ-MONEO E, ROBINSON SM, et al. 2018. Prognosis of sporadic resected small (</=2 cm) nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors - a multi-institutional study. HPB (Oxford), 20, 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMPEDRO-NUNEZ M, SERRANO-SOMAVILLA A, ADRADOS M, CAMESELLE-TEIJEIRO JM, BLANCO-CARRERA C, CABEZAS-AGRICOLA JM, MARTINEZ-HERNANDEZ R, MARTIN-PEREZ E, MUNOZ DE NOVA JL, DIAZ JA, et al. 2018. Analysis of expression of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint system and its prognostic impact in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Sci Rep, 8, 17812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SATO S, TSUCHIKAWA T, NAKAMURA T, SATO N, TAMOTO E, OKAMURA K, SHICHINOHE T & HIRANO S 2014. Impact of the tumor microenvironment in predicting postoperative hepatic recurrence of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Oncol Rep, 32, 2753–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCARPA A, CHANG DK, NONES K, CORBO V, PATCH AM, BAILEY P, LAWLOR RT, JOHNS AL, MILLER DK, MAFFICINI A, et al. 2017. Whole-genome landscape of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Nature, 543, 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGHI AD, LIU TC, RONCAIOLI JL, CAO D, ZEH HJ, ZUREIKAT AH, TSUNG A, MARSH JW, LEE KK, HOGG ME, et al. 2017. Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres and Loss of DAXX/ATRX Expression Predicts Metastatic Disease and Poor Survival in Patients with Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin Cancer Res, 23, 600–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAHASHI D, KOJIMA M, SUZUKI T, SUGIMOTO M, KOBAYASHI S, TAKAHASHI S, KONISHI M, GOTOHDA N, IKEDA M, NAKATSURA T, et al. 2018. Profiling the Tumour Immune Microenvironment in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms with Multispectral Imaging Indicates Distinct Subpopulation Characteristics Concordant with WHO 2017 Classification. Sci Rep, 8, 13166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAO L, XIU D, SADULA A, YE C, CHEN Q, WANG H, ZHANG Z, ZHANG L, TAO M & YUAN C 2017. Surgical resection of primary tumor improves survival of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with liver metastases. Oncotarget, 8, 79785–79792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THEVENON J, BOURREDJEM A, FAIVRE L, CARDOT-BAUTERS C, CALENDER A, MURAT A, GIRAUD S, NICCOLI P, ODOU MF, BORSON-CHAZOT F, et al. 2013. Higher risk of death among MEN1 patients with mutations in the JunD interacting domain: a Groupe d’etude des Tumeurs Endocrines (GTE) cohort study. Human molecular genetics, 22, 1940–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORNS C, SCHURMANN C, GEBAUER N, WALLASCHOFSKI H, KUMPERS C, BERNARD V, FELLER AC, KECK T, HABERMANN JK, BEGUM N, et al. 2014. Global microRNA profiling of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasias. Anticancer Res, 34, 2249–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIROSH A, MUKHERJEE S, LACK J, GARA SK, WANG S, QUEZADO MM, KEUTGEN XM, WU X, CAM M, KUMAR S, et al. 2019. Distinct genome-wide methylation patterns in sporadic and hereditary nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer, 125, 1247–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]