Abstract

Background

The tumor microenvironment (TME) contains a variety of immune cells, which play critical roles during the multistep development of tumors. Histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9) has been reported to have either proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory effects, depending on the immune environment. In this study, we investigated whether HDAC9 in the tumor stroma regulated inflammation and antitumor immunity.

Methods

Hdac9 knockout mice were generated to analyze the HDAC9-associated inflammation and tumor progression. Immune cells and cytokines in TME or draining lymph nodes were quantified by flow cytometry and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. The antigen presentation and CD8+ T cell priming by tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells (DCs) were evaluated in vitro and in vivo. HDAC9-associated inflammation was investigated in a mouse model with dextran sulfate sodium–induced colitis. Correlation of HDAC9 with CD8+ expression was assessed in tissue sections from patients with non-small cell lung cancer.

Results

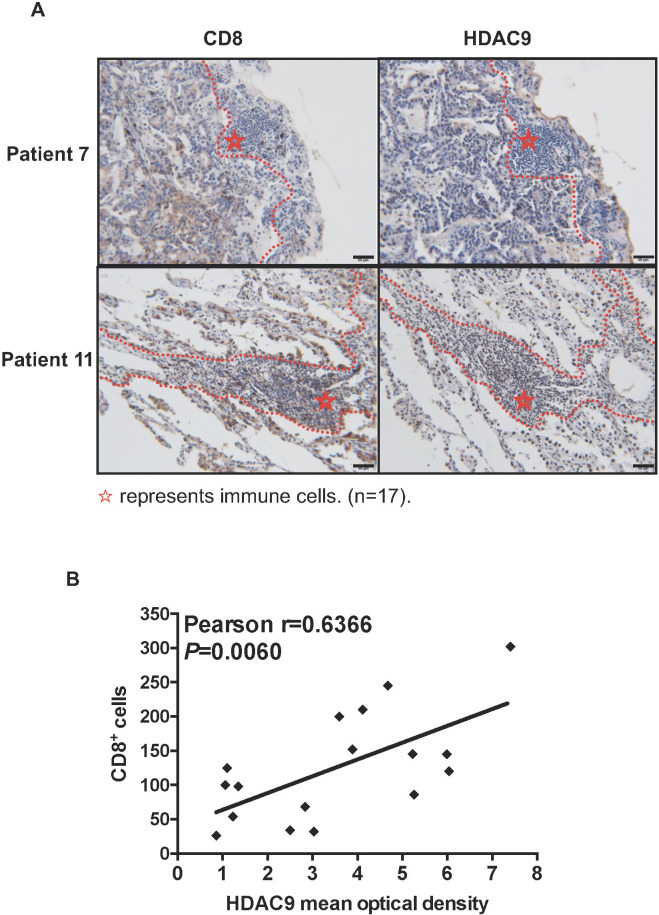

HDAC9 deficiency promoted tumor progression by decreasing the CD8+ DC infiltration of the TME. Compared with wild-type mice, the tumor-infiltrating DCs of Hdac9-/- mice displayed impaired cross-presentation of tumor antigens and cross-priming of CD8+ T cells. Moreover, HDAC9 expression was significantly positively correlated with CD8+ cell counts in human lung cancer stroma samples.

Conclusions

HDAC9 deficiency decreased inflammation and promoted tumor progression by decreasing CD8+ DC infiltration of the TME. HDAC9 expression in the tumor stroma may represent a promising biomarker to predict the therapeutic responses of patients receiving CD8+ T cell-dependent immune treatment regimens.

Keywords: dendritic cells, tumor microenvironment

Background

The tumor microenvironment (TME), which comprises fibroblasts, endothelial cells, immune cells, bone marrow–derived precursor cells, platelets, and other cell types, plays a critical role in the behavior of tumors during their multistep development.1–3 In the TME, tumor cells are confronted by diverse types of immune cells, including effectors of both innate (macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and natural killer (NK) cells) and adaptive (T and B lymphocytes) immunity, through all stages of the disease, from tumorigenesis to progression and metastasis.4 5 MDSCs and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are key barriers to antitumor immunity. TAMs engulf chemotherapy-generated tumor cell debris through phagocytosis and release proinflammatory cytokines to promote tumor progression, and high TAM density has been associated with worse prognosis in several cancer types.6 7 MDSCs expand during tumor initiation and have a remarkably potent ability to suppress various T cell responses.8 They also mediate resistance to treatments targeting vascular endothelial growth factor, supporting angiogenesis.9 Moreover, previous data from us and others have indicated that DC infiltration of tumors might inhibit tumor expansion during early tumorigenesis, but promote tumor growth in later stages due to phenotypic skewing from immune system stimulation to immunosuppression.10–12

Histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9) belongs to the class IIa family of HDACs (including HDACs 4, 5, 7, and 9), which catalyze the removal of acetyl groups from lysine residues in both histone and non-histone proteins, causing transcriptional repression and kinase activation. HDAC9 usually functions in a multiprotein complex with HDAC1 and HDAC3. It has low tissue and cancer specificity and is involved in heart development and the progression of multiple tumors, including breast, liver, and gastric cancers.13–15 According to the Human Protein Atlas,16 HDAC9 is broadly expressed in peripheral blood cells, including DCs, monocytes, neutrophils, B cells, T cells, and NK cells, with the highest level observed in myeloid DCs. HDAC9 is associated with the acetylation status of forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) in the regulation of regulatory T (Treg) cell quantity and function, and has been suggested as a therapeutic target for autoimmune diseases and organ transplantation.17–19 Recently, Li et al 20 found that in innate immunity, high HDAC9 levels in the cytoplasm of primary peritoneal macrophages resulted in increased interferon (IFN) β production via TANK binding kinase 1. Guerriero et al 21 used a mouse model of breast cancer to demonstrate in vivo that the pan-class IIa HDAC inhibitor TMP195 induced the recruitment and differentiation of highly phagocytic and stimulatory macrophages in the TME, resulting in reduced tumor burden. Therefore, HDAC9 has demonstrated both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects in different studies, even in the same cell type. This could be due to differences in the immune environments or immune responses. Given the complicated crosstalk among the diverse immune cells in the TME, it remains unclear how HDAC9 in the tumor stroma regulates antitumor immunity.

In this study, we used Hdac9-knockout (KO) mice to investigate how HDAC9 regulates antitumor immune responses in tumor models, and found that HDAC9 deficiency promotes tumor growth by decreasing CD8+ DCs and T cells in the TME.

Materials and methods

Mice and cell lines

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Cavens Laboratory Animal (Changzhou, China). CD8 ovalbumin T-cell receptor transgenic (Tg) OT-I mice were kindly provided by Professor Hai Qi (Tsinghua University). Hdac9-KO mice were generated in a C57BL/6 background using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 technique, as previously described.22 The single guide RNA sequence was as follows: 5′-CGGACGACAGGATCCACCAC-3′. Mouse sequences were analyzed using Sequencher V.5.4 (GeneCodes, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). Primers used for genomic screening were as follows: forward 5′-GCTTACATGCGCTATTCAGGG3′, reverse 5′CTCCCATGGGTCGGTCTTATG3′. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, and experiments were performed at 6–8 weeks of age. Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells and B16 melanoma cells derived from C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (GIBCO, Nanjing, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biolnd, Nanjing, China). LLC cells were infected with pMiT-ovalbumin retrovirus, packaged in 293 T cells, in the presence of 10 µg/mL polybrene after 24 hours of pretreatment with 250 ng tunicamycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China). Flow cytometry was performed to confirm ovalbumin expression in LLC cells.

Reagents

Recombinant mouse Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3) ligand was purchased from Peprotech (Suzhou, China). Fluorescein-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against CD45 (30-F11), CD11c (N418), CD11b (M1/70), adhesion G protein-coupled receptor E1 (F4/80, BM8), Gr-1, programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1, 10 F .9G2), CD3 (17A2), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53 – 6.7), IFNγ (XMG1.2), and FOXP3 (MF-14); isotype control monoclonal antibodies, and carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) were purchased from Biolegend (Beijing, China); leukocyte activation cocktail (LAC) was purchased from BD Pharmingen (Shanghai, China). Microbead-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against CD8 or CD11c were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec (Shanghai, China). The iTAg Tetramer/PE-H-2Kb OVA (SIINFEKL) detection kit was purchased from MBL (Shanghai, China). Ovalbumin peptide SIINFEKL (OVA257-264), collagenase type IV, hyaluronidase, and deoxyribonuclease were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China). Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; molecular mass 36,000–50,000 Da) was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Beijing, China). Monoclonal antibodies against human CD8 (EP1150Y) and HDAC9 (EPR5223) were purchased from Abcam (Shanghai, China).

Bone marrow–derived dendritic cell culture

The femurs and tibiae of wild-type and Hdac9-/- C57BL/6 mice were harvested and the bone marrow was collected by Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 flushing. Red cell counts were removed by lysis. Bone marrow cells (1×106/mL) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO, Nanjing, China) supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 µM β-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO, Nanjing, China), and 100 ng/mL Flt3-ligand as described previously.12 On day 7, dendritic proliferating clusters were collected and purified using anti-CD11c microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Shanghai, China). The purity of DCs was confirmed to be >90% by flow cytometry.

Tumor models

LLC (2×105), LLC-OVA (3×105), or B16 (1×105) cells suspended in 100 µL of saline solution were subcutaneously inoculated into the right flank of each C57BL/6 or Hdac9-/- mouse. Tumors were measured with a caliper twice weekly, and the volume was calculated as tumor size (mm3) = ab2/2, where a is the length of the longest axis, and the b is the length at a right angle from a. Mice with tumors <300 mm3 were considered to be surviving. CD11c-DTR mice were injected with diphtheria toxin (DT; Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China; 10 ng/g body weight in saline solution), and the next day, bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from wild-type or Hdac9-/- C57BL/6 mice were coinjected with tumor cells as described above. To maintain low levels of endogenous DCs, mice were injected with low-dose DT (4 ng/g body weight) every 3 days. Tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed before the tumor diameter reached 2 cm. Murine tumor protocols complied with all relevant laws and institutional guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Medical University.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis

Flow cytometry

Surface and intracellular molecule staining was performed as previously described.11 Tumors and draining lymph nodes (DLNs) were collected from mice and minced into pieces smaller than 1 mm3, followed by digestion with collagenase type IV, hyaluronidase, and deoxyribonuclease for 30 min at 37°C on a rotating platform. Samples were then filtered through a 70 µm cell strainer and washed twice with staining buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% fetal calf serum and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid). Cells were resuspended in staining buffer, blocked with an Fc-blocking monoclonal antibody for 15 min on ice, and stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies against CD45, CD11c, CD11b, F4/80, Gr-1, PD-L1, CD3, CD4, or CD8 on ice for 30 min. For IFNγ and FOXP3 staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized. OT-I-specific T cells were stained using iTAg Tetramer/PE-H-2Kb OVA (SIINFEKL). After a washing step, flow cytometry was performed on a BD FACSCanto II (San Jose, California, USA). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software V.8 (Tree Star, New Jersey, USA).

OT-I activation assay

OT-I cells were isolated from the spleens and lymph nodes of OT-I mice and CD8+ T cells were purified using Miltenyi magnetic-activated cell sorting system. To functionally identify tumor-associated DCs, single cell suspensions were isolated from mouse tumor tissue by Percoll density gradient centrifugation followed by CD11c+ cell sorting. Tumor-infiltrating DCs were pulsed with 1 µg/mL SIINFEKL peptide (OVA257-264) and cocultured with naïve CFSE-labeled OT-I CD8+ T cells (2.5 µM CFSE for 10 min at 37°C) at a 1:5 ratio (DCs: 0.2×106, T cells: 1×106) in 24-well tissue culture plates for 3–5 days. On the day of detection, cells were restimulated with LAC for 4–6 hours, stained for intracellular IFNγ, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

OVA-specific CD8+ T cell function assay

Single cell suspensions of DLN cells from LLC-OVA tumor-bearing mice were obtained and restimulated in vitro with 1 µg/mL SIINFEKL peptide. After 72 hours of culture, cells were collected and analyzed for intracellular IFNγ expression by flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tumor tissues from 17 patients with lung cancer were obtained with informed consent, using a protocol that complied with relevant ethical regulations and was approved by Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital review board (No. [2018]KY306-01). The microtome was used to prepare 5 µm sections. For antigen retrieval, heat-induced epitope retrieval was conducted in citrate buffer at pH 6 using a boiler. For detection, a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody was used along with the chromogen diaminobenzidine (DAB; Roche, Shanghai, China). The specific binding of an antibody to its antigen resulted in brown staining. Tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and dehydrated with a graded alcohol series and xylene. Fiji software (a distribution of ImageJ) was used to quantify the mean HDAC9 intensity and the number of CD8+ cells.

Induction of intestinal inflammation

DSS colitis was induced by adding 2.5% DSS to the mice’s drinking water for 1 week, followed by normal drinking water for the remainder of the experiment. Body weights were monitored daily over the course of the experiment. At the end of the experimental period, mice were sacrificed, and their colon lengths were measured. Then, a 1 cm segment of the distal colon was immediately embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (SAKURA, Nanjing, China) and frozen. After sectioning into 3 µm sections, colon segments were stained with H&E to assess tissue integrity.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

Sort-purified BMDCs (5×106) were collected in duplicate from wild-type and Hdac9-/- mice. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol and genomic DNA was removed using DNase I (TaKaRa, Beijing, China). RNA quality was determined and high-quality samples (optical density (OD) 260/280=1.8–2.2, OD 260/230≥2.0, RNA integrity number ≥6.5, 28S:18S ≥1.0, >10 µg) were used to construct RNA-seq transcriptome libraries with the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina; San Diego, California, USA), using 1 µg of total RNA. To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between samples from wild-type and Hdac9-/- mice, the expression levels of each transcript were calculated using the fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (FRKM) method. The R statistical package edgeR was used for differential expression analysis. Significant DEGs were defined by a logarithmic fold change >2 with a false discovery rate <0.05. To examine DEG functions, gene ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis was performed in the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery. DEGs were considered significantly enriched in GO terms and metabolic pathways when their Bonferroni-corrected p values were <0.05.

Statistical analysis

The unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance were used for comparisons between two groups. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant. For survival curves, the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used. To determine correlations between HDAC9 levels and CD8+ cells, immunohistochemistry experiments were performed with blinded staining and blinded analysis, and Pearson’s correlation test was used. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism V.7.0 software, and results are the mean±SE of the mean (SEM). No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size.

Results

Hdac9 knockout promotes tumor progression

To analyze the specific role of HDAC9 in tumor progression, we generated stable Hdac9 KO mice using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Deletion of a fragment of Hdac9 exon 5 was confirmed by DNA sequencing (online supplementary figure S1a). Western blot analysis showed complete loss of HDAC9 expression in Hdac9 -/- mice (online supplementary figure S1b).

jitc-2020-000529supp001.pdf (6.9MB, pdf)

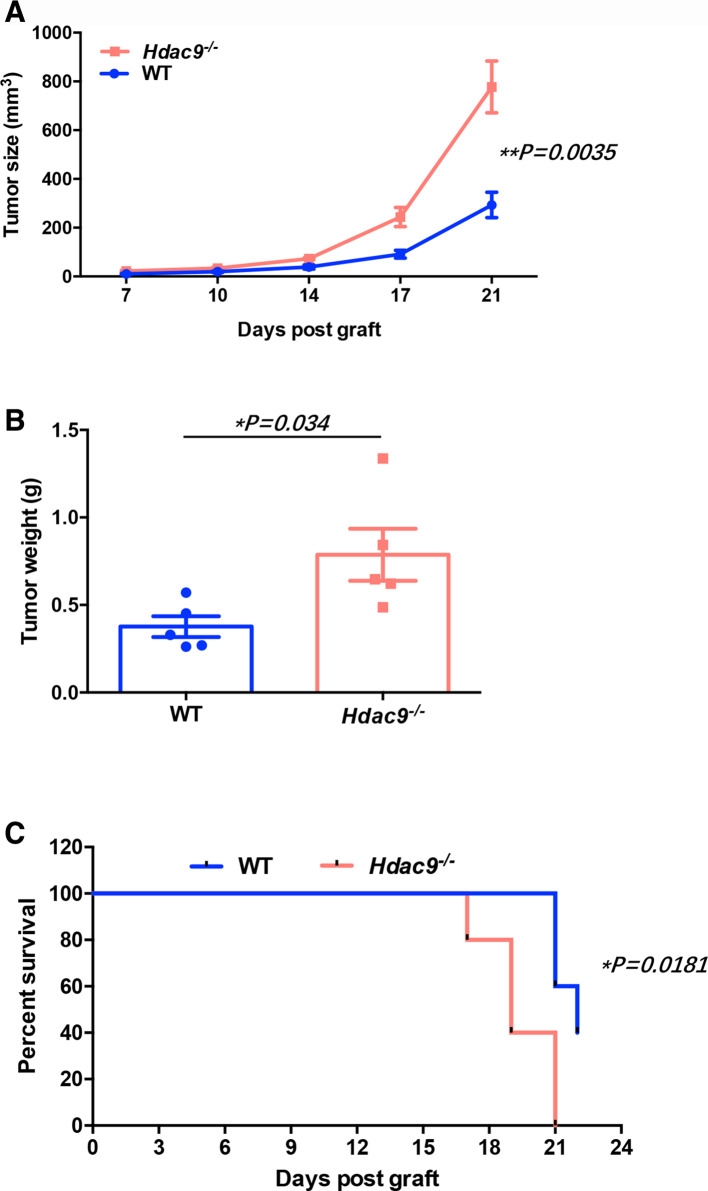

We subcutaneously inoculated LLC cells into wild-type and Hdac9 -/- mice. Compared with wild-type mice, Hdac9 -/- mice displayed faster tumor growth and shortened survival (figure 1A–C). Similar results were observed using B16 melanoma cells (online supplementary figure S2).

Figure 1.

Histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9) deficiency promotes tumor growth in Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) tumor-bearing mice. Wild-type (WT) and Hdac9-/- mice were subcutaneously injected with 2×105 LLC cells (n=5 per group). (A) Tumor growth, (B) tumor weight, and (C) survival time (tumor’s size ≥300 mm3 was considered to the death) were monitored. Representative results from two independent experiments are shown. Data represent the mean±SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test.

Tumor immunosuppression relies on DC-specific HDAC9 deficiency

To examine HDAC9-associated immune effects in vivo, we next quantified the tumor-infiltrating immune cells (CD45+ cells) in these mice. The frequencies of CD3+CD8+ T cells and CD11c+CD8+ DCs in the TME and DLNs were significantly decreased in Hdac9-/- mice compared with wild-type mice, while CD3+CD4+ T cells are not remarkably altered in the HDAC9-deficient mice (figure 2A–C). CD11c+PD-L1+ DCs were markedly increased in the TME of HDAC9-deficient mice, but not in the DLNs. There were no significant differences in the frequencies of total CD11c+ DCs, CD11c+CD11b+ DCs, CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages, CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSCs, T cells, or Treg cells in the TME (online supplementary figure S3a-c). In addition, loss of HDAC9 did not affect the composition of DC subpopulations in naïve mice, nor did it affect the numbers of other immune cells (online supplementary figure S3d). The absence of HDAC9 did not significantly influence the expression of MHCII, CD80, CD40, CD86, CCR7 on the DCs within the tumor (online supplementary figure S3e).

Figure 2.

CD8+ dendritic cells (DCs) are decreased in the tumor microenvironments (TMEs) of tumor-bearing Hdac9-/- mice. The percentages of CD8+ or PD-L1+ cells in DCs (CD11c+ cells) in the TME (A) and draining lymph nodes (DLNs) (B) of Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) tumor-bearing wild-type (WT) or Hdac9-/- mice were determined by flow cytometry. (C) The percentages of CD8+ T cells in the T cell population (CD3+) in the TMEs and DLNs of LLC-bearing mice were determined by flow cytometry. Dot plots were gated on CD45+ cells. (D) The mRNA expression levels of antitumor immune response-related molecules in the TME were determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR and calculated by the 2-ΔCt method. Representative results from three independent experiments are shown. Data represent the mean±SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. *p<0.05. n.s. means no significant difference.

Next, we examined whether the cytokine profiles in the tumor milieu were altered between wild-type and Hdac9-/- mice. Tumors were excised, and the total RNA was extracted for qRT-PCR. As shown in figure 2D, the mRNA levels of cytokines and molecules known to support antitumor immunity, such as IFNγ, GZMB, TBX21, IL12A, and IL12B, were not significantly changed. Interestingly, the production of molecules that suppress the immune response, such as GATA3, NR4A1, FOXP3, TGFβ1, and IL10, was significantly increased, while CD8A mRNA was significantly decreased within the TME of Hdac9-/- mice. These data suggest that HDAC9 is capable of reprogramming immune effects at the tumor site.

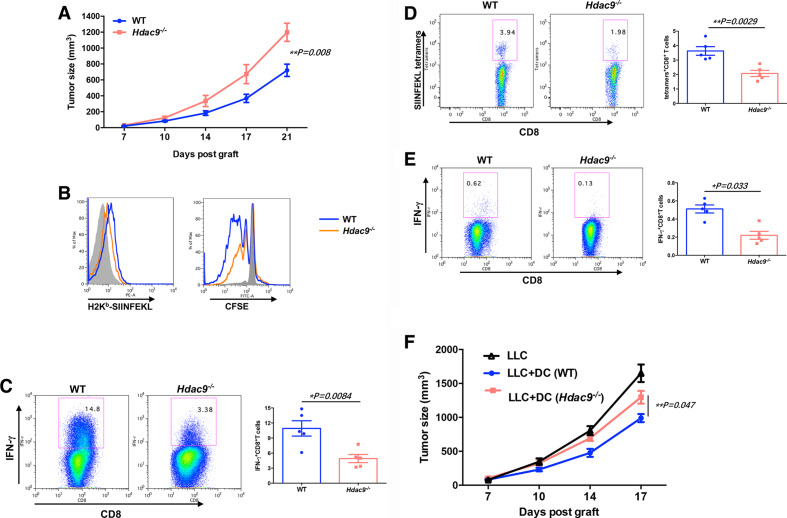

HDAC9 deficiency decreases DCs antigen presentation and CD8+ T cell priming

To investigate whether HDAC9 deficiency reduced DC cross-presentation of tumor antigens, resulting in decreased CD8+ T cell priming, we used the LLC-OVA tumor model (figure 3A) and analyzed the abundance of H2Kb-SIINFEKL complexes on DCs from tumor-bearing wild-type and Hdac9 -/- mice. As shown in figure 3B, H2Kb-SIINFEKL complex levels were significantly lower in tumor-infiltrating Hdac9 -/- DCs than in wild-type DCs, suggesting that DCs from Hdac9 -/- mice possess diminished antigen-presentation activity relative to wild-type DCs. To verify the ability of the DCs to promote CD8+ T cell priming, CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were cocultured with sorted DCs from the TMEs of LLC-OVA tumor-bearing mice. As expected, Hdac9 -/- DCs drastically decreased CD8+ T cell proliferation and differentiation into effector cells, as measured by IFNγ production (figure 3C). These results suggest that loss of HDAC9 decreases the cross-priming capacity of DCs.

Figure 3.

Tumor antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells (DCs) is impaired in Hdac9-/- mice. (A) Wild-type (WT) and Hdac9-/- mice were injected subcutaneously with 3×105 Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC)-OVA cells (n=5 per group), and tumor growth was monitored. (B) H-2Kb-SIINFEKL formation on DCs in the tumor microenvironment (TME) of LLC-OVA tumor-bearing WT or Hdac9-/- mice (left). Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled OT-I CD8+ T cells were cocultured with sorted tumor-infiltrating DCs for 3–5 days, and their proliferation (B, right) and interferon (IFN) γ+ cells (C) were determined by flow cytometry. (D) The frequency of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the TME was analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were gated on CD45+CD3+ cells. (E) Single cell suspensions were prepared from draining lymph nodes (DLNs) and stimulated with SIINFEKL peptide (1 µg/mL) for 3 days. CD8+IFNγ+ cells were determined by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean±SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. (F) To remove CD11c+ DC population, CD11c-DTR recipient mice were intraperitoneally injected with diphtheria toxin (DT) (200 ng/mouse). After 1 day, CD11c-sorted bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) (1×106) from WT or Hdac9-/- mice were subcutaneously coinjected with LLC tumor cells (2×105) into CD11c-DTR mice (n=5 per group). After then, mice were injected with low-dose DT (20 ng/mouse) every 3 days. Representative results from two independent experiments are shown. Data represent the mean±SEM. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance.

To determine whether antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were differentiating in vivo, we assessed the frequency of LLC-OVA tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells expressing the SIINFEKL-major histocompatibility complex-I tetramer in wild-type and Hdac9-/- mice. Compared with wild-type mice, Hdac9-/- mice displayed a substantial decrease in CD8+ T cells activated against the OVA antigen in vivo (figure 3D). Next, lymphocytes from DLNs were restimulated with OVA-derived SIINFEKL peptide in vitro for 3 days. There were significantly less CD8+IFNγ+ T cells in the Hdac9-/- cells than in the wild-type cells (figure 3E), indicating that HDAC9 loss decreases T cell priming against tumor antigens.

To investigate whether the observed immune suppression relies on the specific loss of HDAC9 from DCs, we generated BMDCs from wild-type mice and Hdac9-/- mice using Flt3 ligand. After sorting, BMDCs were subcutaneously coinjected with LLC tumor cells into CD11c-DTR transgenic mice that had been depleted of host DCs expressing CD11c-DTR by administration of DT. Endogenous CD11c+ DC depletion was verified by flow cytometric analysis 24 hours after injection of 200 ng DT or control vehicle (online supplementary figure S4). Notably, although mice injected with Hdac9-/- DCs displayed less tumor growth than mice injected with LLC cells alone, wild-type DCs were much more efficient at preventing tumor progression (figure 3f). These results demonstrate that DCs participate in the impaired antitumor immunity of Hdac9-/- mice.

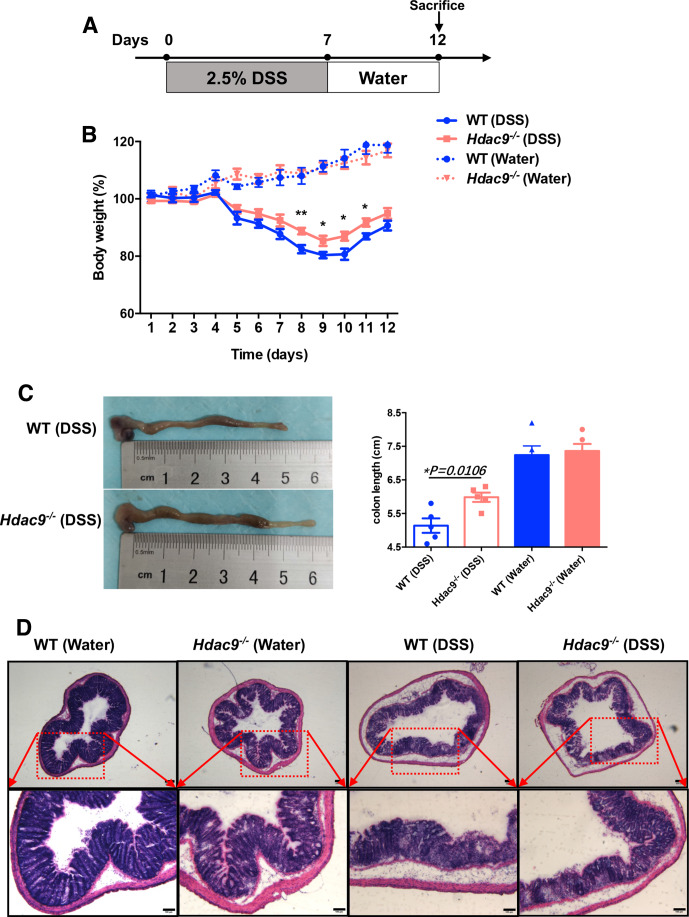

HDAC9 deficiency delays DSS-induced colitis

DC activation is associated with colitis,23 so we next investigated whether HDAC9 is involved in DC-mediated colitis. We challenged wild-type and Hdac9-/- mice with DSS, a widely used chemical irritant that induces intestinal inflammation with the clinical, immunological, and histological features of human inflammatory bowel disease. The protocol is shown in figure 4A. Body weight loss was significantly delayed in Hdac9-/- mice compared with wild-type mice (figure 4B). Reduced colon length often serves as a surrogate macroscopic indication of colonic injury, and we observed significantly longer colons in Hdac9-/- mice than in wild-type mice following DSS treatment (figure 4C). Furthermore, histological analysis of the distal colon demonstrated severe disrupted crypt architecture and abundant inflammatory cell infiltration in DSS-treated wild-type mice, while these phenotypes were alleviated in Hdac9-/- mice, with less crypt loss and decreased immune cell infiltration (figure 4D). These findings demonstrate that HDAC9 deficiency reduces inflammation, inhibiting the onset and clinical signs of DSS-induced colitis.

Figure 4.

Histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9) deficiency prevents dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. (A) Method for colitis induction with DSS in C57BL/6 mice. (B) Body weights of wild-type (WT) and Hdac9-/- mice that received regular drinking water or water containing 2.5% DSS. (C) Colon lengths 12 days after DSS induction (n=5 per group). (D) Representative H&E staining of distal colon sections. Representative results from two independent experiments are shown. **p<0.01, *p<0.05.

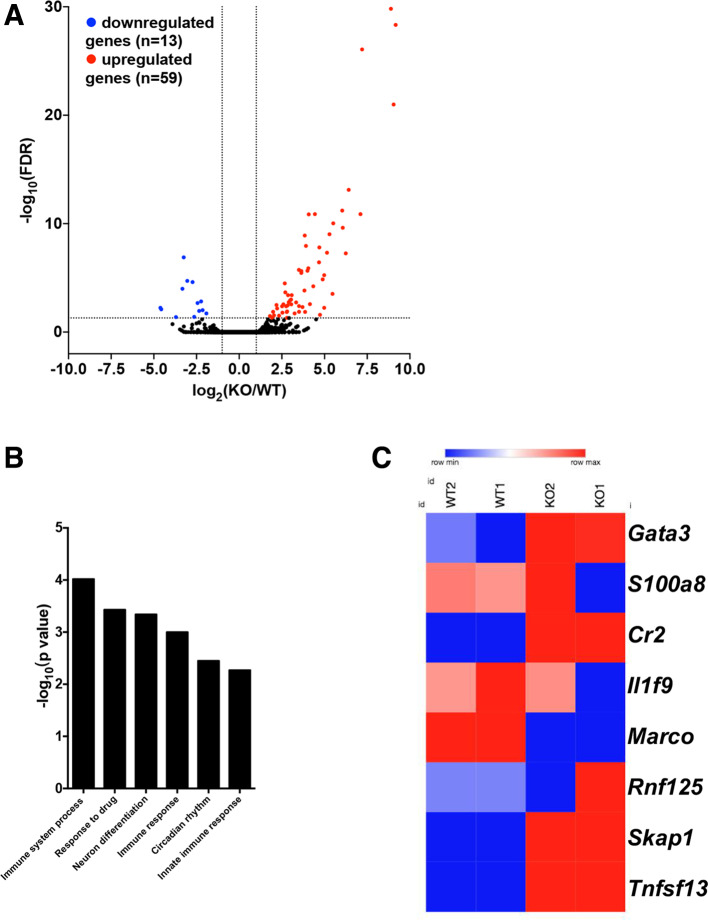

Transcriptome-wide identification and analysis of HDAC9-associated genes in BMDCs

To systematically assess the role of HDAC9 in the regulation of DC immune functions, we next performed RNA-seq to identify DEGs in Hdac9-/- BMDCs compared with wild-type BMDCs. We identified 72 significant DEGs in Hdac9-/- DCs, including 59 upregulated genes and 13 downregulated genes (figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Transcriptome-wide changes in histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9)-deficient bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). (A) Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in wild-type (WT) and Hdac9-/- BMDCs (adjusted p≤0.05, fold change ≥2.0). Statistical significance was determined by two-sided likelihood ratio test (n=4). (B) Gene ontology term enrichment analysis of biological process-associated genes with significantly differential translational efficiency (p≤0.00053 and fold enrichment ≥5.2). (C) Heatmap showing the translational efficiency of genes involved in immune system processes in WT and Hdac9-/- BMDCs (KO1 and KO2 represent replicates). FDR, false discovery rate; KO, knockout.

To identify HDAC9-associated functional pathways, we performed GO term enrichment analysis. As shown in figure 5B, with regard to biological processes, HDAC9-associated transcripts were enriched in pathways associated with immune system processes (particularly the innate response), drug responses, neuronal differentiation, and circadian rhythms. Further analysis revealed that the translation of a group of transcripts responsible for inflammatory responses and antigen recognition was changed in Hdac9-/- DCs compared with in wild-type DCs (figure 5C). Conversely, the translation of costimulatory or inhibitory molecules and cytokines was not significantly altered in Hdac9-/- DCs (data not shown). These data suggest that HDAC9 extensively regulates DC immune functions. Specifically, the transcription of GATA3, which is generally identified as T cell-specific, was dramatically upregulated in DCs with HDAC9 deficiency, as also shown in figure 2C. This indicates that HDAC9 may participate in the regulation of DC differentiation from common myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells.

Low HDAC9 levels are associated with decreased CD8+ T cells in human lung cancer TMEs

To examine the effects of HDAC9 expression on the human TME, we collected tissue sections from patients with non-small cell lung cancer and performed immunohistochemical staining for CD8 and HDAC9. Consistent with the observations in mouse models, patients with low HDAC9 expression in the tumor stroma tended to have a lower number of CD8+ cells than patients with high HDAC9 expression (online supplementary figure S5, figure 6). The mean intensity of HDAC9 in the stroma was positively correlated with the number of CD8+ cells, indicating that low HDAC9 expression might control the amount of T cells in the non-inflamed TME.

Figure 6.

The quantity of CD8+ T cells is positively correlated with HDAC expression in human lung cancer stroma. (A) Tissue sections from patients with lung cancer were immunohistochemically stained for CD8 and histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9). Dashed lines denote tumor edges, and stars mark the stroma. Representative HDAC9-low (patient 7) and HDAC9-high (patient 11) specimens are shown. Scale bars, 50 µm. (B) Correlation between the mean HDAC9 intensity and the quantity of CD8+ T cells in the stroma (n=17 patients). Pearson’s correlation test was used.

Discussion

In previous studies, HDAC9 has been reported as both a positive and negative regulator of immune processes.20 21 24 25 These different results may be due to the functional status and localization of HDAC9, the methods used to interfere with its expression in immune cells, and differences in the local immune microenvironments. In this study, we used CRISPR to disrupt Hdac9 in mice and found that HDAC9 deficiency promoted tumor progression in LLC and B16 tumor models, and provided resistance to DSS-induced colitis, consistent with a previous study.18 In both cases, loss of HDAC9 expression had anti-inflammatory effects.

By analyzing TME immune cell populations, we determined that the quantities of DCs, macrophages, neutrophils, and Treg cells were similar between Hdac9 -/- and wild-type mice. However, the percentages of CD8+ DCs were significantly decreased in the tumors and DLNs of Hdac9-/- mice compared with wild-type mice. Furthermore, when BMDCs from Hdac9-/- and wild-type mice were coinjected with tumor cells into CD11c-DTR mice subjected to DC removal by continuous DT injection, HDAC9-deficient DCs induced less antitumor immunity than wild-type DCs. Taken together, these findings indicate that the impaired adaptive antitumor immune response in Hdac9-/- mice is characterized by decreased differentiation of innate CD8+ DCs. Conventional DCs can be divided into two distinct subsets, cDC1s and cDC2s, depending on whether they express CD103 or CD8.26–28 CD103+ and CD8+ DCs are thought to have identical functions. Studies have reported that cross-presentation of tumor antigens in mice is mainly attributed to cDC1s, which subsequently prime tumor-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.27 29 30 Consistently, CD8+ T cells were decreased in the TMEs and DLNs of Hdac9-/- mice in this study. Recently, Cheng et al 31 proposed that expressing mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 in tumor cells could disrupt the immunosuppressive state of the TME by boosting cDC1- and CD8+ T cell-dependent antitumor immunity. By contrast, Yan et al 32 reported that in the central nervous system, the presence of fibrinogen-like protein 2 in tumor cells inhibited granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced CD103+ DC differentiation and promoted tumor progression. Our data suggest that inducing HDAC9 expression in the tumor stroma through genetic or pharmacological intervention could promote tumor regression.

To study the molecular mechanisms by which HDAC9 regulates CD8+ DC differentiation, we generated BMDCs using Flt3 ligand,33 isolated CD11c+ cells, and analyzed them by RNA-seq. Interestingly, the mRNA level of GATA3 was upregulated in HDAC9-deficient DCs. GATA3 is a transcription factor that is indispensable at several stages of T cell development, and its upregulation suggests that HDAC9 expression in DCs plays a key role in balancing myeloid and lymphoid commitment by suppressing the transcription of lymphoid-related genes, and that this balancing process is associated with CD8+ DC differentiation. Furthermore, these findings indicate the presence of a myeloid-T-progenitor population, as previously suggested.34 Similarly, Onodera et al 35 demonstrated that GATA2 regulates DC differentiation toward the myeloid fate by inhibiting GATA3 expression. Additionally, chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing data indicate that HDAC9 binds an enhancer element 800 kb downstream region of GATA2.36 The precise regulatory relationship between these three molecules will require further investigation.

TMEs that are infiltrated with antigen-specific T cells have been described as T cell-inflamed environments. These environments contain variable numbers of CD8+ T cells and CD8/CD103+ DCs, are promoted in part by CD8+ DCs, and are a marker of susceptibility to immunotherapy.37 38 In contrast, tumors with non-T cell-inflamed TMEs do not benefit clinically from immunotherapy.39 40 The identification of molecular markers associated with non-T cell-inflamed TME is therefore necessary and important for the development of combinational immunotherapy strategies. Consistent with our findings in mice, the HDAC9 expression level in the TMEs of human lung cancer tissues was strongly positively associated with CD8+ T cell infiltration, suggesting that low HDAC9 expression in the tumor stroma could be used to identify non-T cell-inflamed TMEs, which are less responsive to immunotherapy.

In summary, here we have demonstrated that HDAC9 deficiency decreases inflammation and promotes tumor progression by decreasing CD8+ DC infiltration of the TME. Our results suggest that HDAC9 expression levels at tumor sites influence the numbers of CD8+ T cells and cDC1s in these tissues. HDAC9 expression in the tumor stroma may represent a promising biomarker to predict the therapeutic responses of patients receiving CD8+ T cell-dependent immune treatment regimens.

Footnotes

Contributors: YN and JD helped design experiments, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; XS, YX, MS, and CM performed supporting experiments; JC, JP and HJ helped design the experiments; and YN and CQ designed the research, interpreted data, and wrote the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81672799 to CQ and 31500731 to YN); Key Project of Jiangsu S&T Plan (BE2019651 to CQ) and Changzhou High-Level Health Personnel Training Project (2016CZLJ016 to CQ and 2016CZBJ013 to YN).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was carried out in consensus with 'Good Scientific Practice Guidelines' of the Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital, as well as the latest “Declaration of Helsinki”. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the 'Ethics Committee' of the Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital ([2018]KY306-01).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analyzed for this study. Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Individual participant data will be available. All of the individual participant data collected during the trial after deidentification will be shared. Study protocol, statistical analysis plan and analytic code will be available. The data will be available immediately following publication. No end date. Anyone, for any purpose, who wishes to access the data is free to get the data from the corresponding author (qichunjian@njmu.edu.cn).

References

- 1. Boulch M, Grandjean CL, Cazaux M, et al. Tumor immunosurveillance and immunotherapies: a fresh look from intravital imaging. Trends Immunol 2019;40:1022–34. 10.1016/j.it.2019.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giraldo NA, Sanchez-Salas R, Peske JD, et al. The clinical role of the Tme in solid cancer. Br J Cancer 2019;120:45–53. 10.1038/s41416-018-0327-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paluskievicz CM, Cao X, Abdi R, et al. T regulatory cells and priming the suppressive tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol 2019;10:2453. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144:646–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity 2018;48:812–30. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, et al. Tumour-Associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:399–416. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sulciner ML, Serhan CN, Gilligan MM, et al. Resolvins suppress tumor growth and enhance cancer therapy. J Exp Med 2018;215:115–40. 10.1084/jem.20170681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol 2012;12:253–68. 10.1038/nri3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shojaei F, Wu X, Qu X, et al. G-CSF-initiated myeloid cell mobilization and angiogenesis mediate tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF therapy in mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:6742–7. 10.1073/pnas.0902280106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scarlett UK, Rutkowski MR, Rauwerdink AM, et al. Ovarian cancer progression is controlled by phenotypic changes in dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2012;209:495–506. 10.1084/jem.20111413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ning Y, Shen K, Wu Q, et al. Tumor exosomes block dendritic cells maturation to decrease the T cell immune response. Immunol Lett 2018;199:36–43. 10.1016/j.imlet.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ning Y, Xu D, Zhang X, et al. β-glucan restores tumor-educated dendritic cell maturation to enhance antitumor immune responses. Int J Cancer 2016;138:2713–23. 10.1002/ijc.30002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hu Y, Sun L, Tao S, et al. Clinical significance of HDAC9 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Mol Biol 2019;65:23–8. 10.14715/10.14715/cmb/2019.65.4.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salgado E, Bian X, Feng A, et al. Hdac9 overexpression confers invasive and angiogenic potential to triple negative breast cancer cells via modulating microRNA-206. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018;503:1087–91. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xiong K, Zhang H, Du Y, et al. Identification of HDAC9 as a viable therapeutic target for the treatment of gastric cancer. Exp Mol Med 2019;51:1–15. 10.1038/s12276-019-0301-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, et al. Proteomics. tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015;347:1260419. 10.1126/science.1260419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beier UH, Wang L, Han R, et al. Histone deacetylases 6 and 9 and sirtuin-1 control Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function through shared and isoform-specific mechanisms. Sci Signal 2012;5:ra45. 10.1126/scisignal.2002873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Felice C, Lewis A, Armuzzi A, et al. Review article: selective histone deacetylase isoforms as potential therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:26–38. 10.1111/apt.13008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yan K, Cao Q, Reilly CM, et al. Histone deacetylase 9 deficiency protects against effector T cell-mediated systemic autoimmunity. J Biol Chem 2011;286:28833–43. 10.1074/jbc.M111.233932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li X, Zhang Q, Ding Y, et al. Methyltransferase Dnmt3a upregulates HDAC9 to deacetylate the kinase TBK1 for activation of antiviral innate immunity. Nat Immunol 2016;17:806–15. 10.1038/ni.3464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guerriero JL, Sotayo A, Ponichtera HE, et al. Class IIa HDAC inhibition reduces breast tumours and metastases through anti-tumour macrophages. Nature 2017;543:428–32. 10.1038/nature21409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sever L, Radomir L, Stirm K, et al. SLAMF9 regulates pDC homeostasis and function in health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:16489–96. 10.1073/pnas.1900079116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stagg AJ. Intestinal dendritic cells in health and gut inflammation. Front Immunol 2018;9:2883. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beier UH, Angelin A, Akimova T, et al. Essential role of mitochondrial energy metabolism in Foxp3⁺ T-regulatory cell function and allograft survival. Faseb J 2015;29:2315–26. 10.1096/fj.14-268409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sanford JA, Zhang L-J, Williams MR, et al. Inhibition of HDAC8 and HDAC9 by microbial short-chain fatty acids breaks immune tolerance of the epidermis to TLR ligands. Sci Immunol 2016;1:eaah4609. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aah4609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roselli E, Araya P, Núñez NG, et al. TLR3 Activation of Intratumoral CD103+ Dendritic Cells Modifies the Tumor Infiltrate Conferring Anti-tumor Immunity. Front Immunol 2019;10:503. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schlitzer A, Sivakamasundari V, Chen J, et al. Identification of cDC1- and cDC2-committed DC progenitors reveals early lineage priming at the common DC progenitor stage in the bone marrow. Nat Immunol 2015;16:718–28. 10.1038/ni.3200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bajaña S, Turner S, Paul J, et al. Irf4 and IRF8 act in CD11c+ cells to regulate terminal differentiation of lung tissue dendritic cells. J Immunol 2016;196:1666–77. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Böttcher JP, Bonavita E, Chakravarty P, et al. Nk cells stimulate recruitment of cdc1 into the tumor microenvironment promoting cancer immune control. Cell 2018;172:1022–37. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2015;523:231–5. 10.1038/nature14404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheng W-C, Tsui Y-C, Ragusa S, et al. Uncoupling protein 2 reprograms the tumor microenvironment to support the anti-tumor immune cycle. Nat Immunol 2019;20:206–17. 10.1038/s41590-018-0290-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yan J, Zhao Q, Gabrusiewicz K, et al. FGL2 promotes tumor progression in the CNS by suppressing CD103+ dendritic cell differentiation. Nat Commun 2019;10:448. 10.1038/s41467-018-08271-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qi C, Cai Y, Gunn L, et al. Differential pathways regulating innate and adaptive antitumor immune responses by particulate and soluble yeast-derived β-glucans. Blood 2011;117:6825–36. 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawamoto H, Katsura Y. A new paradigm for hematopoietic cell lineages: revision of the classical concept of the myeloid-lymphoid dichotomy. Trends Immunol 2009;30:193–200. 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Onodera K, Fujiwara T, Onishi Y, et al. GATA2 regulates dendritic cell differentiation. Blood 2016;128:508–18. 10.1182/blood-2016-02-698118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Di Giorgio E, Brancolini C. Regulation of class IIa HDAC activities: it is not only matter of subcellular localization. Epigenomics 2016;8:251–69. 10.2217/epi.15.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Luke JJ, Bao R, Sweis RF, et al. WNT/β-catenin Pathway Activation Correlates with Immune Exclusion across Human Cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:3074–83. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu Q, Zhu H, Tiruthani K, et al. Nanoparticle-Mediated trapping of Wnt family member 5A in tumor microenvironments enhances immunotherapy for B-Raf proto-oncogene mutant melanoma. ACS Nano 2018;12:1250–61. 10.1021/acsnano.7b07384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest 2017;127:2930–40. 10.1172/JCI91190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ji R-R, Chasalow SD, Wang L, et al. An immune-active tumor microenvironment favors clinical response to ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012;61:1019–31. 10.1007/s00262-011-1172-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2020-000529supp001.pdf (6.9MB, pdf)