Abstract

The consecutive addition of acyl radicals and N-alkylindole nucleophiles to styrenes was established, as well as some additional radical–nucleophile combinations. Both aryl and aliphatic aldehydes give reasonable yields. The reaction proceeds best for α-substituted styrenes, effectively creating a quaternary all-carbon center. Some iridium-based photoredox systems are catalytically active; furthermore, a base is needed in this transformation. Radicals are formed by reductive perester cleavage and hydrogen atom transfer.

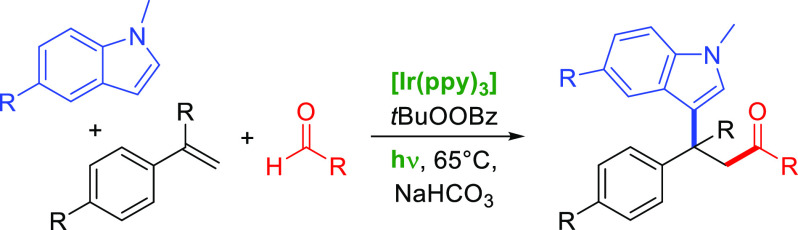

The consecutive addition of a radical and a nucleophile to the C=C bond of an olefin is an interesting method of olefin difunctionalization, as it allows the introduction of two complementary reagents in a single step.1 To accomplish this type of reaction, an oxidation by electron transfer (ET) has to convert the initially formed radical intermediate (1) to the corresponding carbocation [2 (Scheme 1)].

Scheme 1. Reaction Path for Introduction of a Nucleophile into a Radical Styrene Difunctionalization Involving Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT).

A widely used technique for generating different kinds of radicals is hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from the substrate (3) to an oxyl radical, which can be formed from peroxides.2 However, intermolecular difunctionalization reactions applying HAT-derived radicals together with a nucleophile represent a rather poorly developed branch among radical reactions.3 This attracted our attention, as we wanted to contribute to the portfolio of this method. We aimed for a catalytic system that merges a reductive peroxide cleavage with the oxidation of the intermediary olefin-radical adduct 1 to the corresponding carbocation 2. Herein, we present a photoredox method of olefin difunctionalization by addition of radicals formed by HAT together with nucleophiles to styrenes, generating products of type 4, especially β-indolyl ketones (Scheme 1).

Such β-indolyl ketones can be synthesized by conjugate addition of indoles to α,β-enones by Lewis acid catalysis, but these methods rarely provide access to quaternary centers.4

There are a few examples of adding indoles as nucleophiles in radical difunctionalization reactions. A trifluoromethyl-arylation of styrenes with a ruthenium-based photoredox system and Umemoto’s reagent as the radical source can utilize indoles.5 Benzylic radicals generated from pyridinium salts6 and ether radicals generated by HAT3f have been added together with indole nucleophiles. Using Ag2CO3 as an oxidant, α-bromoesters could be used as radical precursors together with N-methylindoles.7 Variations of this method can also be performed by applying iridium-based photoredox catalysis.8N-Methylindoles can also be used as nucleophiles together with aryl radicals made from diazonium salts by photoredox catalysis9 and with cyanomethyl radicals made with Ag2CO3 as the oxidant at increased temperatures.10

Acyl radicals are generated in various fashions, including HAT from aldehydes.11,12 Decarbonylation can take place, especially at elevated temperatures and in the case of branched alkyl aldehydes, generating alkyl radicals. Seminal examples of applying acyl radicals in intermolecular difunctionalization reactions of olefins are an autoxidative addition to acrylate derivatives and an iron-catalyzed reaction forming peroxyketones.13 In photocatalytic intermolecular difunctionalization reactions, acyl radicals generated by HAT have so far been used only for the generation of α-epoxy-ketones.14 Two examples involving acyl radicals in difunctionalization reactions with radicals and nucleophiles have been reported: an alkylation–azidation of styrenes at 110 °C15 and an acylation–imidation using specially designed precursor substrates that deliver both the radicals and the nucleophiles upon photocatalytic activation.16

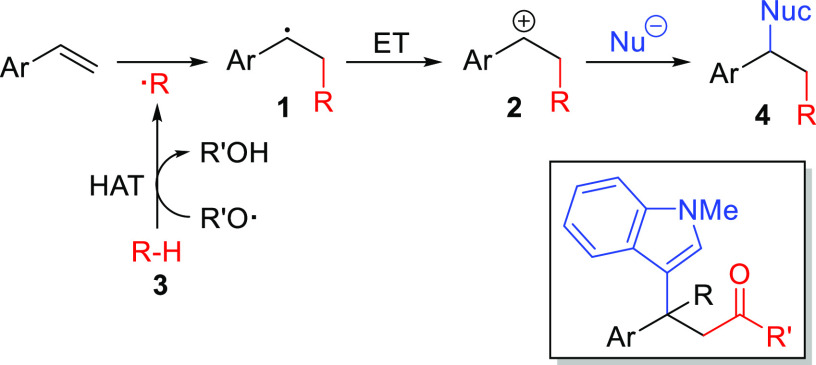

We believed a peroxyester would be most suitable as the oxyl radical precursor, which could be reductively cleaved by ET from a photocatalyst, which would in turn oxidize the radical intermediate. For example, Knowles et al. exploited tert-butyl perbenzoate (TBPB) in a dehydrogenative synthesis of elbasvir, using an iridium photocatalyst.17 On the basis of the redox potentials of the widely used photocatalyst tris(2-phenylpyridinato-C2,N)iridium(III) [Ir(ppy)3] and TBPB [photoexcited Ir(ppy)3*; E1/2 = −1.73 V,18 and E1/2 = −1.40 V19; all potentials given vs SCE], we made a working model for the reaction mechanism (Scheme 2). After irradiation, an ET occurs from the photoexcited Ir(III) species to TBPB, forming Ir(IV), benzoate, and a tert-butoxyl radical. The latter is a good acceptor in HAT reactions,2 thus forming radicals from suitable substrates. These radicals add to styrene derivatives, forming intermediate 1′ (compare to PhC·HCH3, for which E1/2 = 0.37 V20), which can reduce Ir(IV) (E1/2 = 0.77 V18) back to Ir(III) by ET. The carbocation intermediate 2′ thus formed can react with nucleophiles to yield the final products.

Scheme 2. Rationalization of Product Formation.

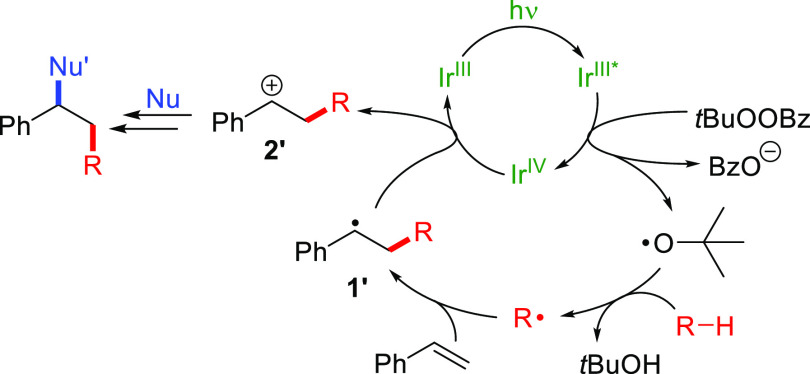

We found that with the combination of Ir(ppy)3 and TBPB in acetonitrile, acyl radicals and N-methylindole add to α-methylstyrene if irradiated with white light-emitting diodes (LEDs) (Scheme 3a). Addition of a base is necessary, and we found NaHCO3 to give best results. The reaction mixture is heated to 65 °C by the LEDs. For a detailed evaluation of reaction conditions, see the Supporting Information.

Scheme 3. Application of Various Aldehydes.

Conditions: olefin (0.5 mmol, 1 equiv), TBPB (2 equiv), Ir(ppy)3 (0.4 mol %), aldehyde (5 equiv), N-methylindole (3 equiv), NaHCO3 (2 equiv), MeCN (5 mL), white LED light, 65 °C, 12 h.

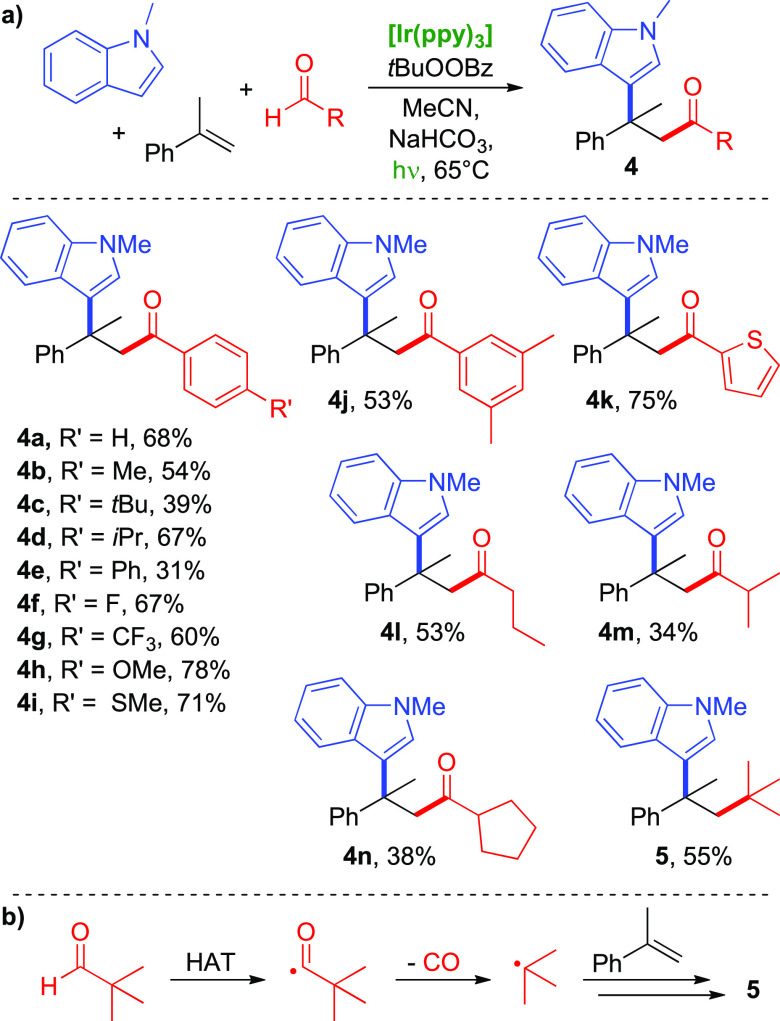

In general, substituted benzaldehydes performed well in this method and the corresponding products (4a–4j) were isolated in yields between 31% and 78%. There is no clear substituent effect on the product yields; the highest were obtained with p-methylsulfide and p-methoxy substituents (4i, 71%; 4h, 78%), but an electron-withdrawing substituent like CF3 also gave a reasonably high yield of 60% (4g). Benzaldehydes bearing an ortho substituent did not provide the desired products. Heteroaromatic 2-thiophenecarboxaldehyde is also quite suitable (4k, 75%), as are primary and secondary aliphatic aldehydes (4l–4n). In contrast, tertiary pivaldehyde led to the decarbonylated product 5. This can be understood by the well-known decarbonylation of acyl radicals, giving a stabilized tert-butyl radical, which then added to the olefin (Scheme 3b). Compared to benzaldehydes, aliphatic aldehydes led to lower product yields (34–55%), presumably due to more reactive radicals.

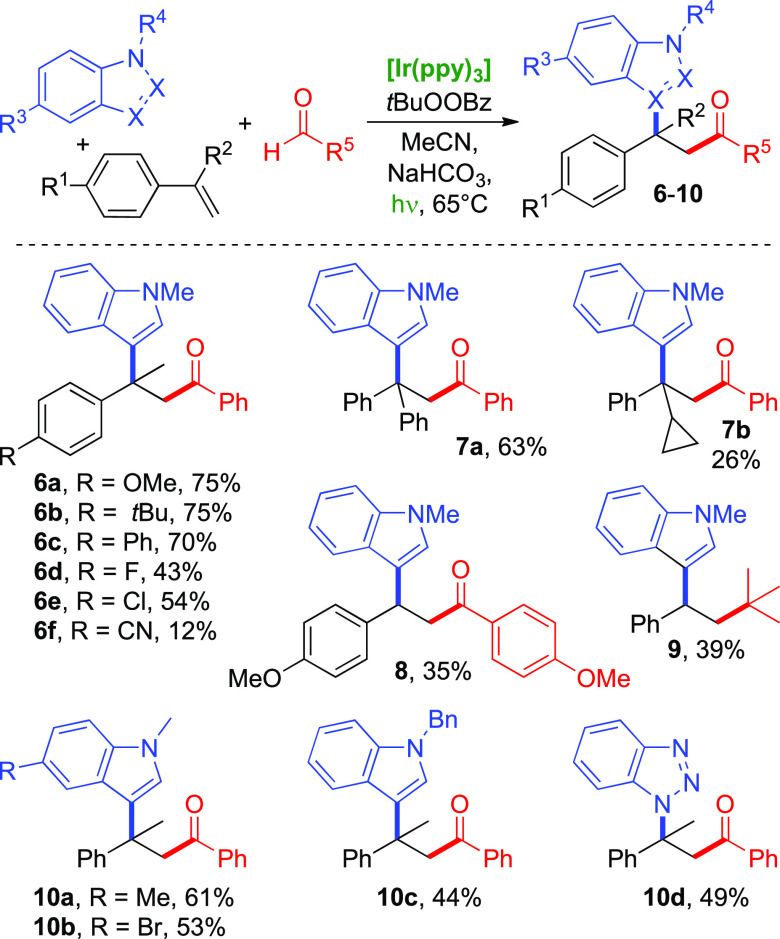

Besides checking the aldehydes’ influence on product formation, we examined para-substituted α-methylstyrenes in the reaction with N-methylindoles and benzaldehyde (Scheme 4). Electron-donating or neutral substituents on the styrenes give good yields (6a–6c), but electron-withdrawing substituents lead to significantly reduced yields (6d–6f). This is in line with the assumed carbocation intermediate 2, which would be stabilized least in the case of a p-CN substituent and which in turn gives the lowest product yield (6f, 12%). Accordingly, 1,1-diphenyl ethylene would lead to a highly stabilized carbocation and the corresponding product is indeed formed in good yield (7a, 63%). X-ray crystal analysis of 7a confirmed the products’ general structure (see the Supporting Information). With α-cyclopropyl styrene, the corresponding product 7b was isolated in only 26% yield, indicating that carbocation formation competes with ring opening of the radical intermediate.

Scheme 4. Application of Various Styrenes and Indoles.

Conditions: olefin (0.5 mmol, 1 equiv), TBPB (2 equiv), Ir(ppy)3 (0.4 mol %), aldehyde (5 equiv), N-methylindole (3 equiv), NaHCO3 (2 equiv), MeCN (5 mL), white LED light, 65 °C, 12 h.

Plain styrene and β-substituted styrenes did not give the desired product with benzaldehyde, which can be explained by the lower degree of stabilization of a secondary carbocation that would be formed in this case. Nevertheless, we could form indolyl ketone 8 from p-methoxybenzaldehyde and p-methoxystyrene, which would react via a secondary cation that is stabilized by the electron-donating substituent. Using pivaldehyde and styrene, the product (9) could be formed, by decarbonylation of the initially formed acyl radical, as shown in Scheme 3b. In contrast, pivaldehyde did not form the analogous product with 1,1-diphenyl ethylene as olefin, possibly due to steric hindrance (see the Supporting Information for a summary of unsuccessful substrate combinations).

In addition, different nucleophiles were evaluated in the reaction of α-methylstyrenes with benzaldehyde. Other electron-rich arenes like methoxy-substituted benzenes and thiophene were not applicable, and neither were alcohols even when used as the solvent. Surprisingly, even slight variations of the indole such as plain indole or N-carbamate-protected indole were unsuccessful (see the Supporting Information for an overview). However, the reaction works well with some N-alkyl indoles like 5-methyl- and 5-bromo-N-methylindole (10a and 10b, respectively) and N-benzyl indole (10c), as well as with benzotriazole (10d).

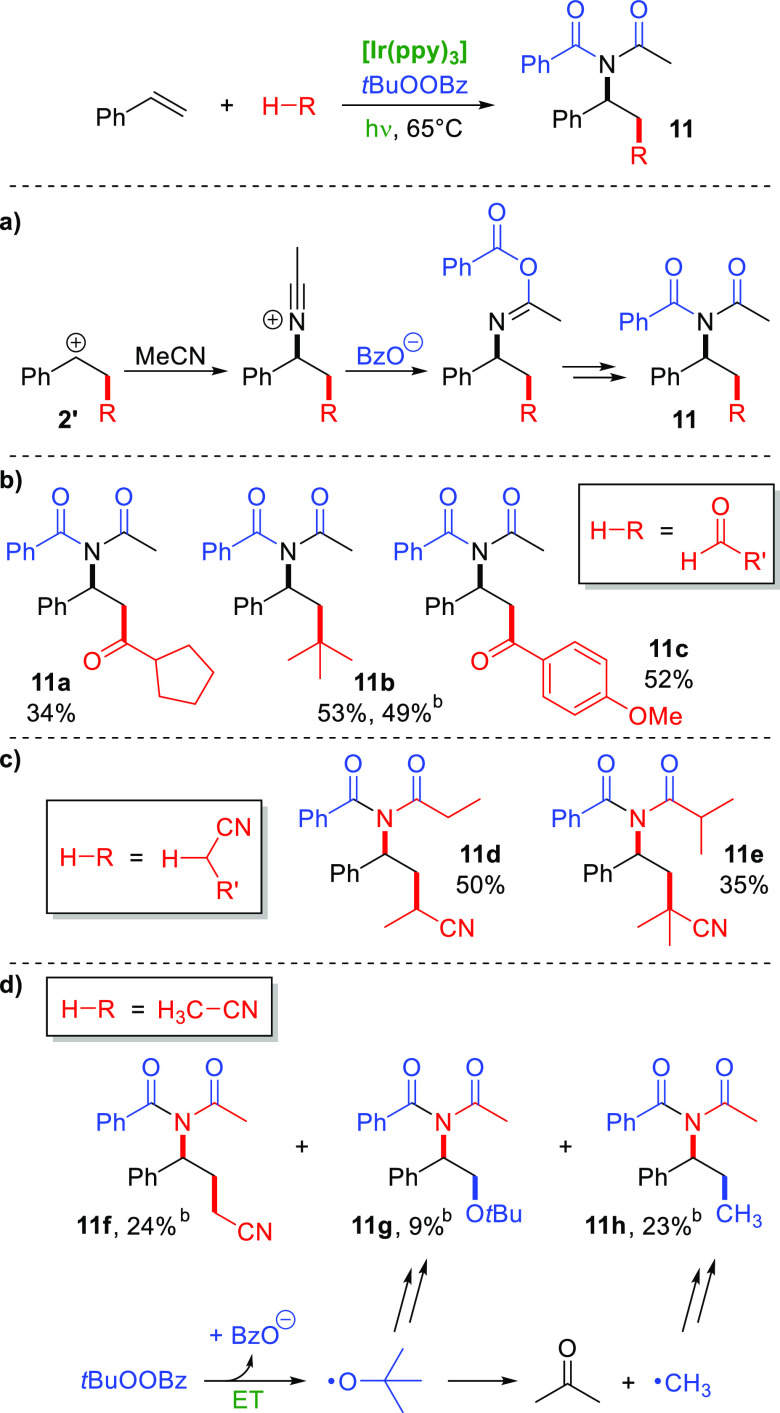

Reactions without addition of indole showed that the solvent acetonitrile could act as a nucleophile (Scheme 5). Interestingly, an N-acyl benzamide was formed, in contrast to an N-acetamide as in a conventional Ritter reaction. This can be explained by attack of acetonitrile on the intermediate carbocation 2′, giving a nitrilium ion, which is attacked by benzoate, giving an imidate that forms the final imide product 11 in a Mumm rearrangement (Scheme 5a).21 Similar imide formations had been observed in intra- and intermolecular reactions.16,22

Scheme 5. Alkyl Nitrile Solvent as a Nucleophile.

Conditions: olefin (0.5 mmol, 1 equiv), TBPB (2 equiv), Ir(ppy)3 (2 mol %), aldehyde (5 equiv), alkyl nitrile (5 mL), white LED light, 65 °C, 20 h.

On a 0.1 mmol scale.

Electron-rich aldehydes worked well in this reaction, providing the keto-imides 11a and 11c as well as the imide 11b via decarbonylation from pivaldehyde (Scheme 5b). Also omitting the aldehyde showed that solvent-derived radicals could also become involved, leading to nitrile products from propionitrile and isobutyronitrile (11d and 11e, respectively) (Scheme 5c). In the case of acetonitrile as the solvent, we could isolate the corresponding nitrile 11f and products 11g and 11h (Scheme 5d). The latter two indicate that radicals formed from the peroxide had become incorporated. Product 11g indicates addition of a tert-butoxyl radical, and 11h addition of a methyl radical, which is known to form from tert-butoxyl radicals by β-scission.23 In general, the imides were obtained in medium yields and only from styrene. With α-methylstyrene, no imide products were formed, possibly due to the low nucleophilicity of acetonitrile.

These results, especially the products shown in Scheme 5, provide important information about the reaction’s mechanism. They support the working model shown in Scheme 2, especially the formation of a benzoate anion and a tert-butoxyl radical, as well as an intermediate benzylic carbocation.

Further support for this mechanistic working model was gained from the following observations. (a) No product was formed in the presence of 1 equiv of the radical inhibitor BHT. (b) Product formation essentially stopped when the light was switched off, and no product was formed when Ir(ppy)3 was substituted with the radical initiators benzoyl peroxide and AIBN, supporting photocatalysis and rather discounting “smart initiation”.24 (c) We observed a larger decrease in luminescence with an increase in TBPB concentration, supporting ET from IrIII* to the peroxide; analysis of the Stern–Volmer relationship25 indicated that more than one quenching mode is operating (for experimental details and extended mechanistic discussions, see the Supporting Information).

To date, it has been very common for methods of radical difunctionalizations of olefins to have strong limitations. With indoles as nucleophiles, the electronic properties of the styrenes show an extraordinarily strong impact. Apart from our work shown here (see 6f above), there is only one procedure that could successfully apply a p-cyano-substituted styrene.3d Most methods are limited to electron-rich styrenes, which is not the case for difunctionalizations with other nucleophiles. There is no simple rationalization of the substrate limitations of such methods yet, hindered by a lack of information. In the work presented here, we could not isolate any characterizable products from reactions with incompatible substrates. Clearly, there is room for future studies in this field.

In summary, we could show that styrene difunctionalization reactions can be realized with a broad scope of aldehyde-derived acyl radicals, in combination with the addition of nucleophiles. This combination had previously not been reported. We were able to show that various functional groups on the styrene can be employed, forming quaternary all-carbon centers upon addition of indoles and benzotriazole to the benzylic position. The stabilization of the carbocation intermediate is a key issue, reflected by the preference for α-substituted styrenes in the case of heteroarene nucleophiles. The case is opposite for alkyl nitriles, which provide imides from α-unsubstituted styrenes only.

Acknowledgments

Support from the DFG (KL 2221/7-1 and Heisenberg scholarship to M.K., KL 2221/4-2) and from the MPI für Kohlenforschung is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Jörg Rust and Conny Wirtz (both MPI für Kohlenforschung) for X-ray crystal analysis and NMR measurements, respectively.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01182.

Experimental details, NMR spectra, crystallographic data, and further mechanistic discussion (PDF)

Accession Codes

CCDC 1978887 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lan X.-W.; Wang N.-X.; Xing Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 5821. 10.1002/ejoc.201700678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Capaldo L.; Ravelli D. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 2056. 10.1002/ejoc.201601485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mayer J. M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 36. 10.1021/ar100093z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Xue Q.; Xie J.; Xu P.; Hu K.; Cheng Y.; Zhu C. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 1365. 10.1021/cs400250m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ha T. M.; Chatalova-Sazepin C.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9249. 10.1002/anie.201604528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhu N.; Wang T.; Ge L.; Li Y.; Zhang X.; Bao H. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4718. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Yang Y.; Song R.-J.; Ouyang X.-H.; Wang C.-Y.; Li J.-H.; Luo S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7916. 10.1002/anie.201702349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Dong Y.-X.; Li Y.; Gu C.-C.; Jiang S.-S.; Song R.-J.; Li J.-H. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 7594. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Su R.; Li Y.; Min M.-Y.; Ouyang X.-H.; Song R.-J.; Li J.-H. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 13511. 10.1039/C8CC08274J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Ouyang X.-H.; Li Y.; Song R.-J.; Hu M.; Luo S.; Li J.-H. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav9839 10.1126/sciadv.aav9839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Liu S.; Klussmann M. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1557. 10.1039/C9CC09369A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Arcadi A.; Bianchi G.; Chiarini M.; D’Anniballe G.; Marinelli F. Synlett 2004, 2004, 944. 10.1055/s-2004-822903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhan Z.-P.; Yang R.-F.; Lang K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 3859. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.03.174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Huang Z.-H.; Zou J.-P.; Jiang W.-Q. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 7965. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.08.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Wu G. L.; Wu L. M. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2008, 19, 55. 10.1016/j.cclet.2007.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Gao Y.-H.; Yang L.; Zhou W.; Xu L.-W.; Xia C.-G. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 23, 114. 10.1002/aoc.1478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni A.; Dagousset G.; Magnier E.; Masson G. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 14197. 10.1039/C4CC07066F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauck F. J. R.; Yoon H.; James M. J.; Lautens M.; Glorius F. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 236. 10.1021/acscatal.8b04191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang X.-H.; Song R.-J.; Hu M.; Yang Y.; Li J.-H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3187. 10.1002/anie.201511624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Li M.; Yang J.; Ouyang X.-H.; Yang Y.; Hu M.; Song R.-J.; Li J.-H. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7148. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Duan Y.; Li W.; Xu P.; Zhang M.; Cheng Y.; Zhu C. Org. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 1443. 10.1039/C6QO00393A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang X.-H.; Cheng J.; Li J.-H. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 8745. 10.1039/C8CC04526G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang X.-H.; Hu M.; Song R.-J.; Li J.-H. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 12345. 10.1039/C8CC06509H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Banerjee A.; Lei Z.; Ngai M.-Y. Synthesis 2019, 51, 303. 10.1055/s-0037-1610329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chatgilialoglu C.; Crich D.; Komatsu M.; Ryu I. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 1991. 10.1021/cr9601425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Also see:; a Majek M.; Jacobi von Wangelin A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2270. 10.1002/anie.201408516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cartier A.; Levernier E.; Corcé V.; Fukuyama T.; Dhimane A.-L.; Ollivier C.; Ryu I.; Fensterbank L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1789. 10.1002/anie.201811858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chudasama V.; Fitzmaurice R. J.; Caddick S. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 592. 10.1038/nchem.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu W.; Li Y.; Liu K.; Li Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10756. 10.1021/ja204226n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Li J.; Wang D. Z. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5260. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b de Souza G. F. P.; Bonacin J. A.; Salles A. G. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 8331. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b01026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.-Y.; Wang Q.-Q.; Yang L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 9987. 10.1039/C7OB02598J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.-Y.; Lei T.; Su L.; Fan X.; Chen B.; Tung C.-H.; Wu L.-Z. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 8789. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yayla H. G.; Peng F.; Mangion I. K.; McLaughlin M.; Campeau L.-C.; Davies I. W.; DiRocco D. A.; Knowles R. R. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 2066. 10.1039/C5SC03350K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike T.; Akita M. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2014, 1, 562. 10.1039/C4QI00053F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R.; Darchen A.; Hauchard D. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 51, 1336. 10.1016/j.electacta.2005.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wayner D. D. M.; McPhee D. J.; Griller D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 132. 10.1021/ja00209a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mumm O. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1910, 43, 886. 10.1002/cber.191004301151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Qin Q.; Han Y.-Y.; Jiao Y.-Y.; He Y.; Yu S. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2909. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang J.; Zhang F.; Lai L.; Cheng J.; Sun J.; Wu J. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3891. 10.1039/C8CC01124A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wu D.; Cui S.-S.; Lin Y.; Li L.; Yu W. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 10978. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b01569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Brandhofer T.; Gini A.; Stockerl S.; Piekarski D. G.; García Mancheño O. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 12992. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b01765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zhang X.; Cui T.; Zhao X.; Liu P.; Sun P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 3465. 10.1002/anie.201913332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See, for example:Baciocchi E.; Bietti M.; Salamone M.; Steenken S. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 2266.and references therein 10.1021/jo0163041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer A.; Curran D. P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 58. 10.1002/anie.201505090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Boaz H.; Rollefson G. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 3435. 10.1021/ja01164a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Moon A. Y.; Poland D. C.; Scheraga H. A. J. Phys. Chem. 1965, 69, 2960. 10.1021/j100893a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.