Amid frenzied national responses to COVID-19, the world could soon reach a critical juncture to revisit and strengthen the International Health Regulations (IHR), the multilateral instrument that governs how 196 states and WHO collectively address the global spread of disease.1, 2 In many countries, IHR obligations that are vital to an effective pandemic response remain unfulfilled, and the instrument has been largely side-lined in the COVID-19 pandemic, the largest global health crisis in a century. It is time to reimagine the IHR as an instrument that will compel global solidarity and national action against the threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogens. We call on state parties to reform the IHR to improve supervision, international assistance, dispute resolution, and overall textual clarity.

First, the COVID-19 pandemic highlights long-standing challenges in the identification of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). The IHR obliges states to notify WHO of any event that may constitute a PHEIC within 24 h after public health authorities' assessment.2 Evidence indicates that some public health authorities in Wuhan, China, suspected what later became known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 for several weeks before WHO was privy to the information.3 Without legal authority to independently visit China and review the outbreak situation, WHO faced a barrier in mounting a cogent global response. In a reimagined IHR, states should allow for information to be received from non-state actors without being subject to verification from the state in question, as currently required by the IHR.2 Moreover, national accountability should be strengthened by mandating independent experts to conduct missions to states so that they can review potential outbreak situations. Arms control treaties bear the strongest examples of such inspection mechanisms, but they have also been wielded in other realms of global health, principally the international drug control regime.4 The concrete links between infectious disease control and global security provide a compelling rationale for an inspection mechanism that encourages states to be more forthright and accountable in reporting a potential PHEIC.5

Relatedly, the process for declaring a PHEIC must be revisited. In a reimagined IHR, states should call for transparency in the deliberations that lead to a PHEIC, by publishing, for example, the transcript of discussion that led to the declaration of a PHEIC.6 Transparency would enhance accountability in the IHR process. Furthermore, states should consider replacing the rigid binary PHEIC architecture, whereby the decision is either no PHEIC or a PHEIC, with an incremental mechanism that would enable intermediate stages for IHR-based alerts and guidance.7 This change would enable greater flexibility and global coordination in responding to disease outbreaks as they unfold.

Second, COVID-19 has shown that all states must invest more domestic resources in their public health systems. Following more than a decade under the revised IHR, only a third of countries meet the core capacities of public health systems required therein,2 impacting countries' abilities to prevent, detect, and respond to disease outbreaks and putting “the whole world at risk”.8 However, even in states where public health core capacities are deemed strong, public health responses to COVID-19 are woefully inadequate.9

Strengthening public health core capacities in all countries demands the concretisation of global solidarity and international support in our shared vulnerability to pathogens.10 States should consider bolstering the IHR provisions for international assistance, including incorporating a financial mechanism to assist low-income countries in building and sustaining required capacities.

To ensure accountability for national capacity building, states should integrate an effective reporting mechanism to monitor implementation of IHR obligations. Robust reporting procedures generally require states to submit periodic national reports on the measures adopted, progress made, and problems encountered in the implementation of a treaty and, crucially, to incorporate some type of independent review. Periodic reporting procedures assist states in identifying and alleviating obstacles they face when implementing commitments, without criticising their performance. International monitoring is crucial for treaty implementation in a wide range of fields and can be imagined as a key mechanism to catalyse cooperation in a post-COVID-19 world. The absence of any provision for such monitoring in the IHR hampers its effectiveness and relevance.

Third, the COVID-19 pandemic confirms how disruptive health measures can be for trade, transport, and economic activities.11, 12, 13 Disputes over the legality of such health measures are likely, and agreed mechanisms to settle them would prevent political tensions from becoming disruptions. Some disputes lend themselves to longer judicial processes, but many would benefit from prompt and practical mechanisms of resolution. The IHR provides a range of options, but these have never been publicly used.2 Multilateral dispute resolution processes, including consultation forums among concerned states and an active good offices role by the WHO Director-General preceding the dispute resolution process, could provide pragmatic solutions.

Fundamentally, states must tackle the overarching issue of ambiguity in the text of the regulations in any future IHR reform process. The widespread lack of clarity with respect to key state obligations in the current IHR undermines compliance by producing a “zone of ambiguity within which it is difficult to say with precision what is permitted and what forbidden”.14

There will soon come a time when negotiators will meet to reimagine the IHR or devise a new legal instrument to promote global cooperation to address infectious disease outbreaks and other global health threats. The challenge should be met head on, not squandered or hidden behind a veil of ambiguity so that a strengthened IHR is better equipped to respond to future global health challenges and acts as an instrument for global solidarity.

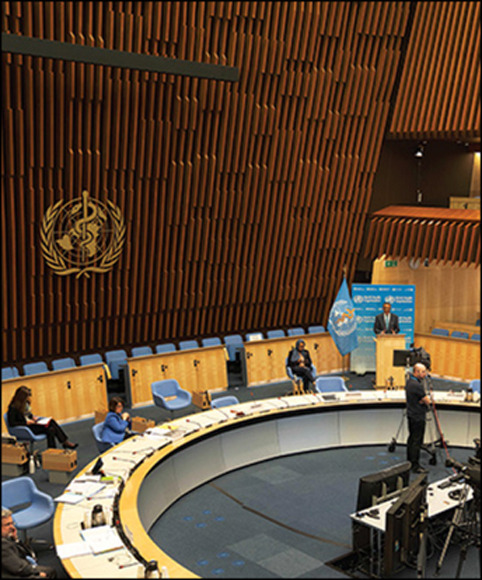

© 2020 Xinhua/Alamy Stock Photo

Acknowledgments

ALT was a legal adviser at WHO and a consultant to WHO on global health law matters. GLB reports personal fees from WHO Regional Office for Europe for consultancy on governance and procedural questions; the fees relate to a consultancy on the governance of the Office and the procedures of the Regional Committee. SD is a member of the WHO research ethics review committee. ME-T previously worked as a consultant to WHO on unrelated matters. AP reports grants and personal fees as past and current consultant to WHO on global and public health law matters, including the IHR. SJH is Scientific Director of the Institute of Population and Public Health at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the agency's Scientific Co-Lead for the COVID-19 Rapid Research Response. The views expressed in this Comment are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of their affiliated institutions. RH, LOG, BMM, PAV, AEY, DC, LF, GO, and SS declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ghebreyesus TA. World Health Organization; 2020. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the World Health Assembly.https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-world-health-assembly [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . 2nd edn. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. International Health Regulations, WHA 58.3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor AL. Addressing the global tragedy of needless pain: rethinking the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. J Law Med Ethics. 2007;35:556–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UN Security Council Security Council Resolution 2177. 2014. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_RES_2177.pdf

- 6.Eccleston-Turner M, Kamradt-Scott A. Transparency in IHR emergency committee decision making: the case for reform. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey F, Ammar W, Endo H. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. Interim Report on WHO's response to COVID-19 January–April 2020.https://www.who.int/about/who_reform/emergency-capacities/oversight-committee/IOAC-interim-report-on-COVID-19.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global Preparedness Monitoring Board A world at risk: annual report on global preparedness for health emergencies. September, 2019. https://apps.who.int/gpmb/assets/annual_report/GPMB_annualreport_2019.pdf

- 9.Aitken T, Chin KL, Liew D, Ofori-Asenso R. Rethinking pandemic preparation: Global Health Security Index (GHSI) is predictive of COVID-19 burden, but in the opposite direction. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.001. published online May 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor A. Oxford handbook of United Nations treaties. 1st edn. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2019. Health; pp. 339–354. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Trade Organization Trade set to plunge as COVID-19 pandemic upends global economy. 2020. https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr855_e.htm

- 12.World Bank . World Bank; Washington, DC: 2020. Global economic prospects.https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Civil Aviation Organization Effects of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) on civil aviation: economic impact analysis. 2020. https://www.icao.int/sustainability/Pages/Economic-Impacts-of-COVID-19.aspx

- 14.Chayes A, Chayes AH. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1998. The new sovereignty. [Google Scholar]