Dear Editor,

SARS-CoV-2 causes an upper respiratory tract infection, spreading by aerosols with coughing, sneezing & exhalation [1]; it has already infected >5 m individuals claiming around 350k lives. Individuals in highly laden healthcare environments have higher infection risk [2]. Concrete data on SARS-CoV-2 transmission via aerosols are lacking; with the potential of faecal viral load of infected individuals surpassing that of aerosols [3], both upper & lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopies are considered high-risk procedures for disease transmission. Therefore, we read with interest the clinical commentary by Cennamo et al. on Redesign of a GI endoscopy unit during the COVID-19 emergency: A practical model [4].

Suspension of non-emergency endoscopies (elective, screening or even urgent/suspected cancer cases) has been widely employed to allow crucial utilisation of human and material resources to areas of immediate COVID-19 care, thus sparing both personal protective equipment (PPE) and medications e.g. midazolam and pethidine/fentanyl the midst of the pandemic. Additionally, meticulous donning & doffing of PPE and extensive cleaning of procedure rooms & equipment after each endoscopy are done at the expense of time, limiting the amount of procedures that can be performed in any allocated list. One can observe an increase in turn-around time of up to 60 min for deep cleaning, reducing total capacity by 50–70%! However, the scale of the macroeconomic impact and ability to deliver human-centred healthcare, considering the detriment of the psychological effect of delayed diagnosis of sinister GI conditions and management guidance in case of chronic conditions cannot be overstated. Furthermore, the growing digestive endoscopy waiting lists, and the potential of medicolegal litigations associated with it, should be taken into account.

Hence, focus should also be given to the use of well-established, minimal-contact, GI diagnostic modalities as a transition to a modern model of care is required. Telemonitoring or telemedicine (TM) facilitates the delivery of healthcare services by providing the transmission of diagnostic information and consultation opportunities at a distance without direct physical contact with an individual or patient. To this end, capsule endoscopy (CE) is a prime example; able to guide (even at the pre-pandemic era) a refined management pathway by rationalising [5,6] the use of conventional/flexible endoscopy, it allows extra confidence in decision-making whilst safeguarding patient interests. The validity of pan-enteric CE for diagnosis, mucosal healing follow-up and/or treatment assessment in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has already been demonstrated [7]. Furthermore, CE can reduce hospital admission rates, hospital stay and provide on-the-spot answer when querying an important upper GI bleed [8]. Admittedly, CE is not an entirely aerosol-free procedure. Occasionally, patients cough or even -very infrequently- aspirate the capsule device [9] . To minimize risks while safeguarding ‘distancing’ until the situation changes, one should employ all the necessary precautions, including live or app-based, remotely guided testing.

Therefore, with the introduction of newest technologies such as wireless body sensors & mobile-cloud-assisted, tele-endoscopic systems patients can follow their daily routines during a spectrum of diagnostic procedures. Evidence has shown that e-consultations is an effective and safe tool that offers the opportunity of delivering care at a distance without direct physical contact with the patient, hence with little risk(s) of spreading infections. For example, in patients with liver cirrhosis a smartphone-based Stroop test has been validated for the diagnosis of covert hepatic encephalopathy [10]. Similarly, a “Patient Buddy App” that monitors symptoms such as weight gain along with medication adherence and daily sodium intake has shown potential to prevent hospital readmissions secondary to hepatic encephalopathy [11]. This intervention showed the ability for TM to reduce 30-d and 90-d readmissions. Additionally, studies have shown that TM enables integrated care for all patients with IBD, regardless of disease severity or medication use [12]. TM helps to educate patients on the importance of measuring physiological parameters and taking their medication. Furthermore, patients learn to recognise a change in themselves, evaluate the symptoms, implement a treatment strategy in collaboration with the medical team and evaluate the response to therapy.

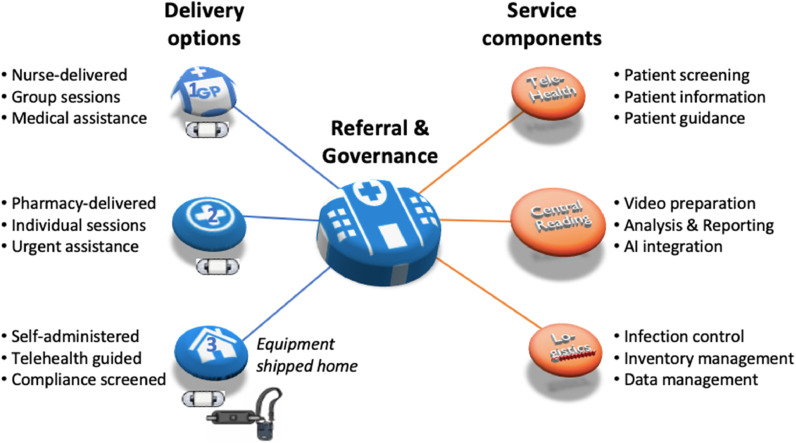

Latest service innovations in CE delivery offer models, economically viable already in ‘pre-crisis’ situations, through extensive use of telehealth for patient interaction, data transfer & video analysis, central pooling of resources and overall minimal capital expenditure [13]. Establishing this modality provides a platform to rapidly adopt further innovation such as artificial intelligence (AI) video reading, allowing therefore stepwise automation from capsule ingestion up to immediate report creation [14], Fig 1 . The road to full recovery will be slow [15]; This pandemic calls for a drastic change of our ‘conventional’ ways, Table 1 . Non-contact or minimal-contact methods are already available, evidently COVID-19 pandemic will speed up further development of such methods.

Fig. 1.

Point-of-care delivery of telemedical-organised capsule endoscopy (CE) examinations. If not at the hospital, CE can be delivered a) at a General Practice (GP) surgery; b) a local pharmacy; c) the patient's residence if compliance can be ensured through screening. Referral, diagnosis and overall governance maintained by GI healthcare service.

Table 1.

Exemplary patient inclusion guidelines during different waves of the pandemic. CCE colon capsule endoscopy; OC optical colonoscopy; FIT faecal immunochemistry test.

| Situation | OC capacity | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Maximum pandemic | 5–10% | Urgent only |

| Phase 2 | Steady-state pandemic | 30–50% | Extra Infection Protection Controls |

| Phase 3 | Post pandemic | 100% | Original capacity (less than demand) |

| FIT | Symptomatic | Symptomatic | Surveillance | Surveillance | Screening | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >=400 μg/g | FIT 20–399 μg/g | FIT <20 μg/g | previous OC- | previous OC+ | FIT+ | |

| Phase 1 | CCE | CCE | Other | – | – | – |

| Phase 2 | OC | CCE | Other | – | OC/CCE | CCE |

| Phase 3 | OC | OC/CCE | CCE/Other | CCE | OC | CCE/OC |

Footnotes

Ethics: This is a letter to editor, expressing opinions of all co-authors, requiring no ethics approval or review and containing no new clinical/patient-related data.

References

- 1.Guo Y.R., Cao Q.D., Hong Z.S. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson N.M., Norton A., Young F.P., Collins D.W. Airborne transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 to healthcare workers: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1111/anae.15093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian Y., Rong L., Nian W., He Y. Review article: gastrointestinal features in COVID-19 and the possibility of faecal transmission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:843–851. doi: 10.1111/apt.15731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cennamo V., Bassi M., Landi S. Redesign of a GI endoscopy unit during the COVID-19 emergency: a practical model [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 16] Dig Liver Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holleran G., Leen R., O'Morain C., McNamara D. Colon capsule endoscopy as possible filter test for colonoscopy selection in a screening population with positive fecal immunology. Endoscopy. 2014;46:473–478. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yung D.E., Koulaouzidis A., Plevris J.N. Earlier use of capsule endoscopy in clinical practice: don't hold back the scouts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:973. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eliakim R. The impact of panenteric capsule endoscopy on the management of Crohn's disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:737–744. doi: 10.1177/1756283X17720860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah N., Chen C., Montano N., Cave D., Siegel R., Gentile N.T. Video capsule endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.03.008. pii: S0735-6757(20)30150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yung D.E., Plevris J.N., Koulaouzidis A. Short article: aspiration of capsule endoscopes: a comprehensive review of the existing literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:428–434. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajaj J.S., Heuman D.M., Sterling R.K., Sanyal A.J., Siddiqui M., Matherly S., Luketic V., Stravitz R.T., Fuchs M., Thacker L.R., Gilles H., White M.B., Unser A. Validation of EncephalApp, Smartphone-Based Stroop Test, for the Diagnosis of Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1828–1835. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.011. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganapathy D., Acharya C., Lachar J., Patidar K., Sterling R.K., White M.B., Ignudo C., Bommidi S., DeSoto J., Thacker L.R., Matherly S., Shaw J., Siddiqui M.S. The patient buddy app can potentially prevent hepatic encephalopathy-related readmissions. Liver Int. 2017;37:1843–1851. doi: 10.1111/liv.13494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Jong M.J., van der Meulen-de Jong A.E., Romberg-Camps M.J. Telemedicine for management of inflammatory bowel disease (myIBDcoach): a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:959‐968. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31327-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wenzek H. Video capsule reporting. At ‘AI in GI – Vision 2020’ conference. Royal College of Physicians, London, 2020 Feb 28. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tqg23Pdi3iI

- 14.SCOTCAP (Scottish Capsule Programme)https://www.dhi-scotland.com/projects/scotcap/ (accessed on 2nd May 2020).

- 15.Luo J. When will COVID-19 end? Data-driven prediction. available fromhttps://lasillarotarm.blob.core.windows.net.optimalcdn.com/docs/2020/04/28/covid19predictionpaper.pdf(assessed 2nd May 2020).