Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine trends in uninsured rates between 2012 and 2016 among low-income adults aged <65 years and to determine whether the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which expanded Medicaid, impacted insurance coverage in the Diabetes Belt, a region across 15 southern and eastern U.S. states in which residents have high rates of diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Data for 3,129 U.S. counties, obtained from the Small Area Health Insurance Estimates and Area Health Resources Files, were used to analyze trends in uninsured rates among populations with a household income ≤138% of the federal poverty level. Multivariable analysis adjusted for the percentage of county populations aged 50–64 years, the percentage of women, Distressed Communities Index value, and rurality.

RESULTS

In 2012, 39% of the population in the Diabetes Belt and 34% in non-Belt counties were uninsured (P < 0.001). In 2016 in states where Medicaid was expanded, uninsured rates declined rapidly to 13% in Diabetes Belt counties and to 15% in non-Belt counties. Adjusting for county demographic and economic factors, Medicaid expansion helped reduce uninsured rates by 12.3% in Diabetes Belt counties and by 4.9% in non-Belt counties. In 2016, uninsured rates were 15% higher for both Diabetes Belt and non-Belt counties in the nonexpansion states than in the expansion states.

CONCLUSIONS

ACA-driven Medicaid expansion was more significantly associated with reduced uninsured rates in Diabetes Belt than in non-Belt counties. Initial disparities in uninsured rates between Diabetes Belt and non-Belt counties have not existed since 2014 among expansion states. Future studies should examine whether and how Medicaid expansion may have contributed to an increase in the use of health services in order to prevent and treat diabetes in the Diabetes Belt.

Introduction

The Diabetes Belt is an important region for public health interventions to reduce health disparities (1). It consists of 644 counties across the southern and eastern U.S. with a prevalence of diabetes ≥11% in 2007–2008; throughout the rest of the country, the prevalence was 8.5%. This area is populated by substantially more non-Hispanic African Americans than the rest of the country (23.8% vs. 8.6%), and its population has a higher prevalence of obesity (32.9% vs. 26.1%) and sedentary lifestyle (30.6% vs. 24.8%) (1). The Diabetes Belt roughly coincides with two of the “Eight Americas” described by Murray et al. (2,3) and the Institute of Medicine (4), namely, low-income whites in Appalachia and blacks in the rural South. Populations in these two regions are known to have shorter life expectancy at birth than the rest of America: 71.8 and 67.7 years for men and 77.8 and 74.6 for women in Appalachia and the rural South, respectively, compared with 76.2 for men and 81.1 for women in the rest of America (2). Murray et al. (2,3) linked a high risk of mortality in these areas to high chronic disease burden.

Access to care and lack of health insurance coverage have been identified as the main reasons for health disparities in the Diabetes Belt. Care of diabetes is often complicated and costly because patients tend to have multiple coexisting conditions and complications and be managed with multiple medications. Insurance coverage for patients with diabetes is important because it alleviates the cost burden on patients and improves access to care (5–8). According to the National Health Interview Survey, 84.7% of U.S. adults who have diabetes and are <65 years of age had health insurance in 2009, and ∼2 million adults with diabetes were uninsured (9). Two years after Medicaid expansion began under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), health insurance coverage increased to 90.1% in this patient population (10). There are still no data on how Medicaid expansion has affected insurance coverage for low-income adults <65 years old who live in the Diabetes Belt.

Our aim in this study was to investigate the impact of Medicaid expansion on insurance coverage among low-income adults <65 years of age who live in the Diabetes Belt compared with those who live outside the Belt.

Research Design and Methods

Study Sample and Data Sources

All counties in the U.S. were designated either as Medicaid expansion counties or nonexpansion counties (see Medicaid Expansion). For all counties, we obtained county-level estimates of health insurance coverage for 2012 through 2016 from the Census Bureau’s Small Area Health Insurance Estimates (SAHIE) program (11). This period represents 2 years before and 2 years after the year Medicaid expansion was implemented under the ACA (2014). Currently, SAHIE is the only source of single-year estimates of health insurance coverage in the U.S. Since 2008, SAHIE has used health insurance data collected in annual American Community Surveys (ACS) and other sources to produce consistent estimates for tracking annual changes in health insurance coverage in the U.S. Estimation methods and data sources are described in detail elsewhere (12,13).

County-level demographic and socioeconomic data were obtained from the Area Health Resources Files (AHRF) compiled by the Health Resources and Services Administration, part of the Department of Health and Human Services (14), and from the Distressed Communities Index (DCI) (15). The DCI is a data set that includes information on the economic well-being of U.S. communities; it combines seven metrics (percentage of the population with no high school diploma, housing vacancy rate, percentage of adults who are not working, poverty rate, median income ratio, change in employment, and change in business establishments) derived from ACS 5-year estimates and county business patterns data into one measure of community economic well-being (16).

Medicaid Expansion

Under the ACA, Medicaid eligibility was expanded to cover all people with household incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). Twenty-six states and the District of Columbia initially expanded Medicaid in 2014. Medicaid coverage became effective on 1 January 2014 in all of these states except Michigan, which started coverage on 1 April 2014, and New Hampshire, which began coverage 1 August 2014. Five more states expanded Medicaid by the end of 2016: Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Alaska in 2015; Montana and Louisiana in 2016. Among 15 states in the Diabetes Belt, six (Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia) have expanded Medicaid and nine have not. In this study, we defined the 24 states and the District of Columbia that initially expanded Medicaid on 1 January 2014 as Medicaid expansion states; we defined all others as nonexpansion states. For the two states that expanded Medicaid in 2014, we used the majority rule in terms of the number of months with expanded Medicaid coverage, given that ACS insurance coverage data are collected throughout the year; we included Michigan as an expansion state and New Hampshire as a nonexpansion state. To test whether and how the classification of these and other states that expanded Medicaid later might have affected the trends in uninsured rates, we conducted sensitivity analyses that 1) reclassified New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Alaska as expansion states; and 2) excluded states that expanded after 1 January 2014 through 2016. Among the expansion states, Arizona, Arkansas, Iowa, New Mexico, Ohio, and Michigan expanded via Section 1115 waivers to operate their Medicaid expansion programs through private insurance. In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to exclude the five states (California, Connecticut, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Washington) and the District of Columbia that implemented comprehensive early expansions (17–19).

Identification of Diabetes Belt and County Types

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention include in the Diabetes Belt 644 counties across 15 southern and eastern states (1): Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia, and the entire state of Mississippi.

We identified Diabetes Belt counties in SAHIE and AHRF using the Federal Information Processing Standard state and county codes. One Belt county and 21 non-Belt counties were excluded from this study because AHRF or SAHIE did not include data for them.

We placed all counties into four groups according to their Medicaid expansion and Diabetes Belt status: Medicaid expansion/non-Belt counties, Medicaid expansion/Belt counties, nonexpansion/non-Belt counties, and nonexpansion/Belt counties.

Covariates

For multivariable analyses, we included demographic covariates that could potentially influence uninsured rates in our multivariable models. Information on covariates including sex, age (18–49 vs. 50–64 years), and percentage of the county population living at or below 138% of the FPL (20) were obtained from the SAHIE data files for 2012 through 2016. We used county-level data from AHRF for race (percentage of total adult population who were non-Hispanic white in 2010), marital status (percentage married in 2010), and urban/rural classification. We used the Rural-Urban Continuum Codes to classify counties into metropolitan, nonmetropolitan, and rural groups. In addition, we used the DCI community economic level to classify counties into five groups (distressed, at risk, mid-tier, comfortable, and prosperous), which we used as indicators of economic well-being in the counties.

Statistical Analysis

For unadjusted trends, we computed weighted averages of uninsured rates for each year for the four types of counties (i.e., the Medicaid expansion and Diabetes Belt combinations) using county total adult population as the weight. For multivariable analyses, we combined county-level annual health insurance data for 2012 through 2016 to form repeated data (five records per county). The number of uninsured adults in each county during each year was modeled by using a two-level random intercept Poisson model with the logged total county population as the offset. The model controlled for potential confounders of the combined data to account for autocorrelation and clustering at the county level. We included interaction terms in the model between year and county types to obtain any differential effects of Medicaid expansion in Belt and non-Belt counties over time.

To obtain trends in adjusted uninsured rates, we estimated marginal means (commonly known as least squares means) of the number of uninsured individuals each year in the four types of counties from the Poisson model (21). These means were compared across county types and years by using the χ2 likelihood ratio test. P values were adjusted by using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The average treatment effects were computed separately for Diabetes Belt and non-Belt counties as absolute differences in the change in uninsured rates between 2012 and 2016 in Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states (22).

Because of concerns about overdispersion and the robustness of our results, we estimated identical two-level random intercept models using negative binomial and linear regressions. We used the number and proportion of uninsured people among the county population as dependent variables for negative binomial and linear regressions, respectively. Estimated marginal means from these regressions were very similar to those obtained from the Poisson model, and our conclusions were robust to the estimation methods used. For this reason, we present results from the Poisson regression. Full regression estimates and their estimated marginal means are shown in Supplementary Tables 4–6.

This study was approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board. We used Stata/SE version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for statistical analyses.

Results

After exclusion, the study sample included 3,129 counties (99.3% of the 3,151 counties in the U.S.): 1,180 counties in Medicaid expansion states and 1,949 counties in nonexpansion states. During 2012 through 2016, uninsured rates in the U.S. declined by 8% among the overall population and by 15% among those with incomes at or below 138% of the FPL. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of this low-income population in the four county types. Supplementary Table 1 has the same information for all income levels. Figure 1 shows the unadjusted trends in uninsured rates for the low-income population by Medicaid expansion and Diabetes Belt status for 2012 through 2016. Henceforth we focus on the insurance status of those with incomes at or below 138% of the FPL—the intended target of the Medicaid expansion policy. The sensitivity analysis showed that the results were similar regardless of whether states that expanded Medicaid in 2014–2016, after the initial 1 January 2014 expansion date, were included as expansion states or nonexpansion states or were excluded from the analysis (see Supplementary Figs. 4–6). Additional sensitivity analysis showed that results remained similar when the five states and the District of Columbia, where comprehensive early expansion occurred, were excluded from the analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Table 1.

Unadjusted uninsured rates and socioeconomic characteristics of the county population living at or below 138% of the federal poverty line, by Medicaid expansion and Diabetes Belt status, 2012–2016

| Variables | Medicaid expansion states | Nonexpansion states | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Diabetes Belt | Non-Belt | Total | Diabetes Belt | Non-Belt | |

| Counties, n | 1,180 | 143 | 1,037 | 1,949 | 500 | 1,449 |

| Total population in 2012, n | 21,286,925 | 758,213 | 20,528,712 | 20,122,367 | 3,917,968 | 16,204,399 |

| Uninsured rates (%) by year, mean (SD) | ||||||

| 2012 | 34.6 (8.5) | 39.3 (4.2) | 33.9 (8.7) | 42.0 (8.1) | 40.4 (5.0) | 42.5 (8.9) |

| 2013 | 33.6 (8.3) | 38.5 (4.1) | 32.9 (8.5) | 41.2 (8.2) | 39.9 (5.3) | 41.7 (8.9) |

| 2014 | 23.0 (5.8) | 21.4 (3.1) | 23.2 (6.1) | 36.4 (7.8) | 35.8 (4.8) | 36.6 (8.6) |

| 2015 | 16.9 (5.3) | 15.0 (3.0) | 17.2 (5.5) | 31.9 (8.7) | 31.2 (4.9) | 32.1 (9.6) |

| 2016 | 14.8 (4.6) | 13.1 (2.3) | 15.1 (4.8) | 29.4 (8.8) | 28.7 (5.2) | 29.7 (9.7) |

| Demographic factors (%), mean (SD) | ||||||

| Age 50–64 years | 28.3 (5.5) | 31.2 (3.4) | 27.9 (5.7) | 28.5 (5.5) | 30.1 (4.4) | 28.0 (5.8) |

| Female sex | 55.1 (2.1) | 55.5 (2.1) | 55.1 (2.1) | 55.7 (2.5) | 57.0 (2.2) | 55.3 (2.5) |

| DCI, n (%) | ||||||

| Prosperous | 272 (23.1) | 1 (0.7) | 271 (26.1) | 353 (18.1) | 16 (3.2) | 337 (23.3) |

| Comfortable | 264 (22.4) | 3 (2.1) | 261 (25.2) | 362 (18.6) | 31 (6.2) | 331 (22.8) |

| Mid-tier | 258 (21.9) | 23 (16.1) | 235 (22.7) | 368 (18.9) | 58 (11.6) | 310 (21.4) |

| At risk | 209 (17.7) | 34 (23.8) | 175 (16.9) | 417 (21.4) | 124 (24.8) | 293 (20.2) |

| Distressed | 177 (15.0) | 82 (57.3) | 95 (9.2) | 449 (23.0) | 271 (54.2) | 178 (12.3) |

| Urban-rural classification of counties, n (%) | ||||||

| Rural | 210 (17.8) | 37 (25.9) | 173 (16.7) | 424 (21.8) | 92 (18.4) | 332 (22.9) |

| Micropolitan | 519 (44.0) | 75 (52.5) | 444 (42.8) | 812 (41.7) | 232 (46.4) | 580 (40.0) |

| Metropolitan | 451 (38.2) | 31 (21.7) | 420 (40.5) | 713 (36.6) | 176 (35.2) | 537 (37.1) |

Supplementary Table 1 shows the matching numbers for all income levels. DB, Diabetes Belt.

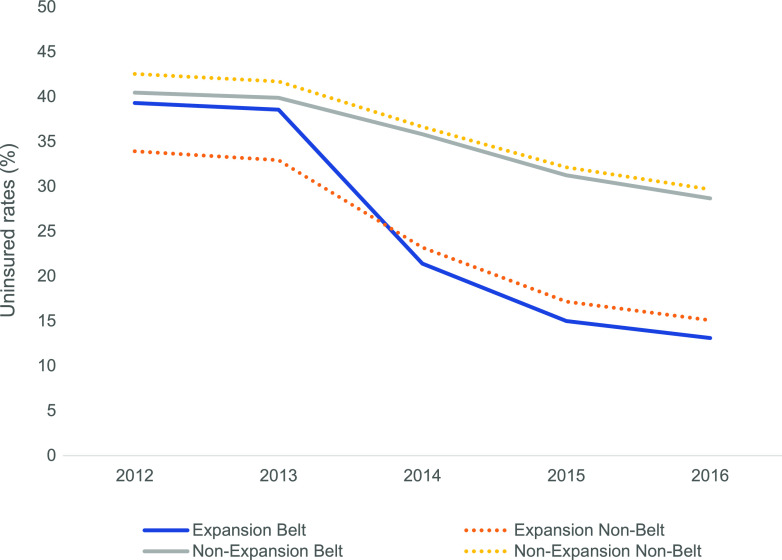

Figure 1.

Unadjusted uninsured rates for county adult populations living at or below 138% of the federal poverty line, 2012–2016.

In 2012, expansion states had significantly lower crude uninsured rates than did nonexpansion states (35% vs. 42%; P < 0.001). The rate of decrease was much greater in expansion states than nonexpansion states. In 2016, the uninsured rate was 15% in the expansion states and 29% in the nonexpansion states (P < 0.001) after absolute reductions of 20% and 13%, respectively, since 2012.

Of all county types, non-Belt counties in expansion states had the lowest (34%) and non-Belt counties in nonexpansion states had the highest (43%) uninsured rates in 2012. After 2014, uninsured rates decreased in all four types of counties.

Among expansion states, Belt counties had higher uninsured rates than non-Belt counties before Medicaid expansion (39% vs. 34% in 2012; P < 0.001). Initial disparities in uninsured rates between Belt and non-Belt counties were completely eliminated in 2014 (21% vs. 23%; P < 0.001), with Belt counties enjoying rates about 2% lower than those in non-Belt counties.

In nonexpansion states during the same period, uninsured rates declined significantly but much more modestly in both Belt (from 40% to 29%; P < 0.001) and non-Belt (from 43% to 30%; P < 0.001) counties than in expansion states. Trends in Belt and non-Belt counties paralleled each other, and no divergence or crossing seemed to occur during this period.

Counties in expansion states were similar to counties in nonexpansion states in terms of age and sex distributions of their populations. However, economic well-being and rural/urban status differed considerably by Medicaid expansion status. The percentage of prosperous counties was higher among expansion states (23%) than nonexpansion states (18%) (P < 0.001), whereas the percentage of distressed counties was higher in nonexpansion states (23%) than in expansion states (15%) (P < 0.001). Interestingly, Belt counties were much more likely to be distressed (57%) than prosperous (1%) in expansion states, whereas non-Belt counties were more prosperous (26%) than distressed (9%) in nonexpansion states. In expansion states, 26% of the population resided in rural areas in Belt counties and 17% in rural areas in non-Belt counties, whereas 18% and 23% lived in such areas, respectively, in nonexpansion states.

Table 2 shows adjusted least squares means of county-level uninsured rates estimated from a Poisson regression model (see Supplementary Table 2 for the full model). Adjusted uninsured rates in Belt counties changed from 37.5% in 2012 to 13.3% in 2016 in expansion states; they changed from 39.5% to 27.5% in nonexpansion states. The average treatment effect, or the net absolute reduction in uninsured rates, due to Medicaid expansion was 12.3% (95% CI 10.9–13.7%) in Belt counties and 4.9% (95% CI 4.4–5.3%) in non-Belt counties. It is noteworthy that this low-income population in both Belt and non-Belt counties in nonexpansion states experienced uninsured rates that were ∼15% higher than those in expansion states.

Table 2.

Adjusted marginal estimated means of county uninsured rates by Medicaid expansion and Diabetes Belt status, income ≤138% of FPL, 2012 through2016

| County type | Year | ATE* (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ||

| Diabetes Belt | ||||||

| Nonexpansion | 39.5 | 38.8 | 34.7 | 30.3 | 27.5 | 12.3 (10.9–13.7) |

| Expansion | 37.5 | 36.4 | 21.1 | 15.1 | 13.3 | |

| Non-Belt | ||||||

| Nonexpansion | 43.0 | 42.1 | 36.8 | 32.2 | 30.2 | 4.9 (4.4–5.3) |

| Expansion | 33.6 | 32.5 | 24.2 | 18.1 | 15.9 | |

Data are percentages.

The average treatment effect (ATE) was computed as the difference in uninsured rates between 2012 and 2016 between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states. We estimated ATEs separately for Diabetes Belt and non-Belt counties. The 95% CIs were corrected for multiple comparisons by using Bonferroni methods. P values are not shown because they were <0.001 for all pairwise comparisons between 2012 and subsequent years, and between adjacent years within county type, and for all pairwise comparisons across county types within the same year after Bonferroni correction. The full model from which these marginal means were derived is shown in Supplementary Table 2.

When all income levels were considered, however, the change was much more modest. Medicaid expansion helped to achieve an absolute reduction in uninsured rates of 4.8% (95% CI 4.0–5.6%) in Belt counties and of 1.6% (1.4–1.9%) in non-Belt counties in 2012–2016 (Supplementary Table 3).

Conclusions

Our results show that Medicaid expansion was significantly associated with reductions in uninsured rates for all counties—over and above secular trends in the uninsured rates in the U.S.—in 2012 through 2016. During this period, states that expanded Medicaid achieved an absolute reduction of 20 percentage points in uninsured rates, whereas states that did not achieved a 13% absolute reduction among the population with an income at or below 138% of the FPL. Adjusting for county demographic and economic factors, Medicaid expansion helped reduce uninsured rates by 12.3 percentage points in the Diabetes Belt counties and by 4.9 percentage points in the non-Belt counties. Initial differences in uninsured rates between Belt and non-Belt counties did not exist anymore the 1st year the policy was in effect in Medicaid expansion states, and uninsured rates fell further during each successive year in both Belt and non-Belt counties. By 2016, uninsured rates were almost 15 percentage points higher in both Belt and non-Belt counties in the nonexpansion states than in the expansion states. During the same period, overall uninsured rates also dropped significantly in all income groups in expansion states.

Numerous studies have shown that uninsured rates in the adult population <65 years old significantly declined after the ACA was implemented in 2010 (23). Since then insurance coverage has improved substantially among low-income populations and ethnic minorities (24,25). Medicaid expansion since 2014 has also helped to further increase insurance coverage for the low-income population (26). One study looking at the effect of expansion in Kentucky found that uninsured rates decreased by 8.3 absolute percentage points between 2013 and 2015, and disparities in uninsured rates between blacks and other races did not exist in 2015 (27). Medicaid expansion also improved insurance rates among minority groups, particularly Latinos in California (28). These studies, along with our results, suggest that expansion had its intended effect of increasing insurance coverage among low-income populations and racial/ethnic minorities in various parts of the country. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that the initial disparities in uninsured rates between Diabetes Belt and non-Belt counties were completely eliminated in 2014, the 1st year of Medicaid expansion.

Whether and how improved insurance coverage in the Diabetes Belt would lead to improved care and health for patients in that region is still an open question. Previous studies have shown that increased access to health care is generally associated with improved diagnosis and treatment of diabetes (29,30), greater adherence to medication regimens, fewer emergency room visits, and more outpatient visits (8). Greater access to care also seems to improve medication use for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia and leads to improved laboratory test results and blood pressure readings (31).

According to some studies, increased insurance coverage after Medicaid expansion had positive effects on access to care. Luo et al. (32) showed that Medicaid expansion helped increase insurance coverage for patients with diabetes, who attended more annual checkups in expansion states than in nonexpansion states. However, the same study found that expansion did not lead to more utilization of preventive care such as eye exams, foot exams, A1C tests, or influenza vaccinations. Other studies have shown that access to care after Medicaid expansion may be dependent on race/ethnicity (33) and rurality (34). Despite increases in insurance coverage after Medicaid expansion, improvements in access to care were not statistically significant among patients in rural areas. More studies are needed in order to determine whether better insurance coverage would ultimately lead to better care and better health specifically for patients in the Diabetes Belt.

Our results have implications for policy and clinical practice. Medicaid expansion has had its intended effect of increasing insurance coverage among low-income populations. In 2014, only 4 of the 15 states with Diabetes Belt counties expanded Medicaid. Since 2014, eight more states have expanded Medicaid, three of which (Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Louisiana) have counties that are included in the Diabetes Belt (35). Eight states that contain Diabetes Belt counties are not expanding Medicaid at this time. Medicaid expansion may help realize more equity in insurance coverage between Belt and non-Belt areas in these states. It is yet to be seen whether improved insurance coverage will eventually lead to more equity in diabetes prevalence and diabetes complication rates between Belt and non-Belt counties.

This study has several limitations. The Diabetes Belt region was defined on the basis of data from 2007 to 2008; it is possible that the boundaries would be different if redefined according to data from the study period (2012 through 2016). The number of Diabetes Belt counties that expanded Medicaid was relatively small compared with the number of non-Belt counties that did so. Because states made decisions to expand Medicaid in part on the basis of awareness of the health care needs of the population and the financial burden on the state, extrapolation of our results to Belt and non-Belt counties in the nonexpansion states must be done carefully (36,37). One concern with our approach may be our decision to use a random intercept model as opposed to a fixed effects specification. We compared the coefficients obtained from the fixed effects with our main results, and the point estimates were nearly identical (see Supplementary Table 7). We also performed a Hausman test to judge the efficiency gains from the random intercept model against the potential reduction in bias from using the fixed effects approach (38,39); we failed to reject the null, allowing us to conclude that our random intercept results are consistent. Because of data limitations, we cannot assess the level of insurance coverage and actual use of insurance, and as a result we are unable to examine whether Medicaid expansion has affected access to care and utilization of services. However, minimum insurance requirements established through the ACA ensure preventive care for all patients and other important provisions for patients with diabetes, including diabetes screening, medication adherence assessment, and a 20% copay for all diabetes-related preventive care. Some expansion states had partial or comprehensive expansion programs in place before 1 April 2014. These states with early expansion might have affected the trends in uninsured rates in a way that we did not describe in this report. To check this, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding the District of Columbia and the five states with comprehensive early expansion; the results were remarkably similar to those reported in this article. Furthermore, this study did not directly evaluate the effects of the ACA on uninsured rates of low-income people with diabetes, because of a lack of available data. Last, only 2 years of data before the expansion were available for this study. Given the limited data, it is difficult to assume whether the trends in the counties we found would have been the same in the absence of expansion.

Conclusion

Before the ACA, individuals living in the Diabetes Belt had higher uninsured rates than those living in non-Belt counties in Medicaid expansion states. Medicaid expansion was associated with its intended effect on health insurance coverage for the low-income population in the Diabetes Belt, consistent with the rest of the country. The initial disparities between Diabetes Belt and non-Belt counties in the Medicaid expansion states did not exist anymore after Medicaid expansion. More studies are needed in order to examine whether the improved insurance coverage among the low-income population in the Diabetes Belt helped reduce the prevalence of diabetes and the number of diabetes complications.

Supplementary Material

Article Information

Funding. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under grant number R01-DK-113295.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Economic Innovation Group. The Economic Innovation Group does not guarantee the accuracy or reliability of, nor necessarily agrees with, the information provided herein. The funder had no role in study design, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. J.M.L. and M.-W.S. conceived the study. J.M.L., S.K., G.O., and M.-W.S. wrote the manuscript. S.K. conducted statistical analysis. All authors designed and interpreted the study, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved this version for publication. M.-W.S. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. Data from this study were presented in poster form at the 79th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, San Francisco, CA, 7–11 June 2019.

Footnotes

This article contains supplementary material online at https://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc19-0874/-/DC1.

References

- 1.Barker LE, Kirtland KA, Gregg EW, Geiss LS, Thompson TJ. Geographic distribution of diagnosed diabetes in the U.S.: a diabetes belt. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:434–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Kulkarni S, Ezzati M. Eight Americas: new perspectives on U.S. health disparities. Am J Prev Med 2005;29(Suppl. 1):4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C, et al. . Eight Americas: investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Med 2006;3:e260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine Challenges and Successes in Reducing Health Disparities: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu R, Shi L, Rane S, Zhu J, Chen CC. Insurance, racial/ethnic, SES-related disparities in quality of care among US adults with diabetes. J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:565–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polonsky WH. Poor medication adherence in diabetes: what’s the problem? J Diabetes 2015;7:777–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polonsky WH, Henry RR. Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:1299–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after Medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1501–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stark Casagrande S, Cowie CC. Health insurance coverage among people with and without diabetes in the U.S. adult population. Diabetes Care 2012;35:2243–2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casagrande SS, McEwen LN, Herman WH. Changes in health insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act: a national sample of U.S. adults with diabetes, 2009 and 2016. Diabetes Care 2018;41:956–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowers L, Gann C, Upton R. Small area health insurance estimates: 2016. In Current Population Reports. Washington, DC, U.S. Census Bureau, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauder M, Luery D, Szelepka S. Small Area Estimation of Health Insurance Coverage in 2010-2016. Washington, DC, U.S. Census Bureau, Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powers D, Bowers L, Basel W, Szelepka S. Medicaid and CHIP data methodology for SAHIE models. In SAHIE Working Papers. Washington, DC, U.S. Census Bureau, Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health Resources and Services Administration Area Health Resources File. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Economic Innovation Group 2018 Distressed Communities Index. [Internet], 2019. Available from https://eig.org/dci. Accessed 21 March 2019.

- 16.Economic Innovation Group Distressed Communities Index methodology. [Internet], 2019. Available from https://eig.org/dci/methodology. Accessed 21 March 2019.

- 17.Sommers BD, Arntson E, Kenney GM, Epstein AM. Lessons from early Medicaid expansions under health reform: interviews with Medicaid officials. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev 2013;3: mmrr.003.04.a02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golberstein E, Gonzales G, Sommers BD. California’s early ACA expansion increased coverage and reduced out-of-pocket spending for the state’s low-income population. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:1688–1694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikpay S, Buchmueller T, Levy H. Early Medicaid expansion in Connecticut stemmed the growth in hospital uncompensated care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:1170–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frean M, Gruber J, Sommers BD. Premium subsidies, the mandate, and Medicaid expansion: coverage effects of the Affordable Care Act. J Health Econ 2017;53:72–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Searle SR, Speed FM, Milliken GA. Population marginal means in the linear model: an alternative to least squares means. Am Stat 1980;34:216–221 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wooldridge JM. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kominski GF, Nonzee NJ, Sorensen A. The Affordable Care Act’s impacts on access to insurance and health care for low-income populations. Annu Rev Public Health 2017;38:489–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sommers BD, Buchmueller T, Decker SL, Carey C, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act has led to significant gains in health insurance and access to care for young adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, Musco T. Changes in self-reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA 2015;314:366–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wherry LR, Miller S. Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions: a quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:795–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blewett LA, Planalp C, Alarcon G. Affordable Care Act impact in Kentucky: increasing access, reducing disparities. Am J Public Health 2018;108:924–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sommers BD, Chua KP, Kenney GM, Long SK, McMorrow S. California’s early coverage expansion under the Affordable Care Act: a county-level analysis. Health Serv Res 2016;51:825–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Geiss LS, Cheng YJ, Beckles GL, Gregg EW, Kahn HS. The missed patient with diabetes: how access to health care affects the detection of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1748–1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Bullard KM, Gregg EW, et al. . Access to health care and control of ABCs of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1566–1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatch B, Marino M, Killerby M, et al. . Medicaid’s impact on chronic disease biomarkers: a cohort study of community health center patients. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:940–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo H, Chen ZA, Xu L, Bell RA. Health care access and receipt of clinical diabetes preventive care for working-age adults with diabetes in states with and without Medicaid expansion: results from the 2013 and 2015 BRFSS. J Public Health Manag Pract. 20 June 2018 [Epub ahead of print] DOI: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yue D, Rasmussen PW, Ponce NA. Racial/ethnic differential effects of Medicaid expansion on health care access. Health Serv Res 2018;53:3640–3656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benitez JA, Seiber EE. US health care reform and rural America: results from the ACA’s Medicaid expansions. J Rural Health 2018;34:213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norris L. Medicaid coverage in your state. [Internet], 14 September 2019. Available from https://www.healthinsurance.org/medicaid/. Accessed 21 March 2019.

- 36.Jacobs LR, Callaghan T. Why states expand Medicaid: party, resources, and history. J Health Polit Policy Law 2013;38:1023–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark CR, Ommerborn MJ, A Coull B, Quyen Pham D, Haas JS. Income inequities and Medicaid expansion are related to racial and ethnic disparities in delayed or forgone care due to cost. Med Care 2016;54:555–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baltagi BH. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data. Chichester, West Sussex, U.K., John Wiley & Sons, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics Using Stata. College Station, TX, Stata Press, 2010 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.