Abstract

Tourist pressure on local populations, also termed ‘overtourism’, has received much attention in the global media, as tensions related to social, economic or environmental change have grown in many destinations. While protests against tourists and tourism development have existed for decades, these are now often more organised, vocal, and politically active. As a phenomenon associated with residents' negative views of tourism development outcomes, socio-psychological foundations of overtourism have so far been insufficiently considered. This paper summarises the historical background on crowding and attitudes of residents to tourism, to then discuss social psychological theories connected to place change in order to explain anti-tourism sentiment.

Keywords: Crowding, Social psychology, Overtourism, Social density, Resident attitudes

Highlights

-

•

Discusses ‘overtourism’ as an outcome of place change

-

•

Uses social psychology theory to interpret resident reactions as emotional responses

-

•

Finds that place change leads to loss of perceived control over place identity

-

•

Suggests that overtourism responses are place-protective actions

Introduction

Tourism is under almost a constant global media spotlight in recent years. 2017 saw the beginning of a worldwide debate on the desirability of continued tourism growth prompted by widespread media coverage of anti-tourist protests in major cities and destinations associated with high levels of tourist demand, crowding at certain sites, and tensions between locals and destination stakeholders. In the first six months of 2020, virtually all global travel and tourism completely halted due to the spread of Coronavirus. In 2017/2018, the global media was quick to lambast the tourism industry for the problems that ‘overtourism’ wrought to local communities, sparking a worldwide scrambled to identify management solutions (e.g., UNWTO, 2018; WTTC & McKinsey, 2017), and intense academic scrutiny about the causes, consequences and policy responses and management of overtourism (e.g. Butler & Dodds, 2019; Peeters et al., 2018). By the early summer of 2020, the discourse had changed to highlight the plight of destinations and communities whose economic dependency on tourism put the focus firmly back on the need to restart tourism as critical to economic recovery. With jobs worldwide at risk, the importance of tourism to the global economy has been put in stark and alarming context (UNWTO, 2020). Against the background of a global restart of tourism in the summer of 2020, and industry hopes of a return to business-as-usual, this paper seeks to discuss the social-psychological foundations of overtourism phenomena.

Protests directed at mass tourism are not new, indeed, they have been documented in a European context in Spain, Italy, Malta and France since at least the 1990s (Boissevain, 1996a, Boissevain, 1996b). However, it appears that recent sustained high levels of tourism growth have led to a tipping point being reached in some destinations, leading to increasingly negative attitudes being expressed among significant segments of the population. These new protests now involve communities, social movements, neighbourhood associations and activist groups, such as the Assembly of Neighbourhoods for Sustainable Tourism (ABTS) or the Network of Southern European Cities against Touristification (SET) (Colomb & Novy, 2016; Seraphin, Sheeran, & Pilato, 2018). Recent vocal anti-tourism campaigns have been recorded in many destinations which were historically accepting of large volumes of tourists in the world's major destination countries, including; France, Spain, Italy and Germany (Füller & Michel, 2014; Gravari-Barbas & Jacquot, 2016; Novy, 2016; Sans & Russo, 2016; Vianello, 2016).

Since the sustained growth of global tourism demand continues unabated, leading to concentrations in specific places, crowding phenomena now have a sense of urgency (Muler Gonzalez, Coromina, & Galí, 2018; Usher & Gómez, 2017). Tourism organisations have pointed to the large influx of tourists in some destinations, highlighting the problems faced by residents, and the need to “disperse” visitors (UNWTO, 2018: 8). However, given the stated desirability of continued tourism growth among organisations such as UNWTO (UNWTO, 2018), much attention has been paid to the management of tourist flows (Butler & Dodds, 2019; Peeters et al., 2018; World Economic Forum, 2017; WTTC & McKinsey 2017), with relatively little focus provided on the underlying socio-psychological foundations that might explain or account for attitudes towards tourists, leading to a more integrative conceptualisation of overtourism. Current responses to overtourism tend to focus on destination policy and management at the expense of a broader understanding of the possible social psychological causes of crowding-induced stress.

This paper contends that a socio-psychological conceptualisation of tourist pressure is needed to understand the dimensions underlying negative resident perceptions. The theoretical focus of the paper is on the social psychology of place perceptions, and linkages to tourism-related change. It is argued that such a perspective complements the current partial adequacy of existing theories in providing effective frameworks to explain resident attitudes towards tourism (García, Vázquez, & Macías, 2015). Building on McKercher, Wang, and Park's (2015) observation that attitudes to tourism are related to place change, this paper provides a historical overview of research on resident-visitor interrelationships, to then discuss social psychological theories that explain emotional responses to tourism.

The consequences of tourism growth: a brief overview

Four books may be considered crucial in the historical context of ‘overtourism’. During the early 1970s, i.e. a time of turbulence in travel and transport caused by the oil crisis, inflation, and global economic recession, these books all warned of the potential negative outcomes that could result from a continued expansion in demand for international travel. In France, this was Haulot's (1974) Tourisme et Environment, in Switzerland, Krippendorf's (1975) Die Landschaftsfresser, as well as, in the UK, Tourism: Blessing or Blight? (Young, 1973) and The Golden Hordes (Turner & Ash, 1975). All correctly identified that demand for tourism would continue to grow, and that such growth would require careful planning and management to mitigate the effects of mass tourism on the environment and societies. The effect of these books was to cement the issue of tourism growth and its relationships with social attitudes as a function of place governance, management and planning rather than a human/environment relationship.

Young (1973) foresaw severe social, environmental, and economic consequences for destination regions without controls on growth and proactive regional planning and management. Growth could only be managed through a global tourism policy, which would optimize tourist flows, be integrated with national and regional policies to distribute tourist demand, and thus minimize conflicts. Turner and Ash's (1975) The Golden Hordes argued along similar lines, that demand for tourism would become democratised to include the ‘ordinary’ classes, whose volumes would become so vast, that destinations would be unable to cope. This argument corresponded to Haulot (1974) and Krippendorf's (1975) central critique, that as tourist flows grew, so would the impact on the environment, consuming resources and land, resulting in a radical change to traditional socioeconomic systems. While these texts all are located within the temporal context of the very early stages of the expansion in international tourism, annual growth rates subsequently ballooned.

At the time these popular books were published, the nascent tourism industry and academy were growing, and largely dismissive of the main concerns of the ideas put forward by these writers. In the 1970s, tourism was still at the ‘advocacy’ stage (Jafari, 1990), and focused on the many benefits that it could bring to (often) peripheral regions with few options for other forms of development. Yet even at the time, academic consideration of the impacts of tourism development on host communities was emerging as a foundational area of concern in relation to the implications of tourism (Butler, 1974). Doxey (1975) published the ‘Irridex’, a theory on how attitudes of residents towards the presence of tourists in a community would change from a welcoming acceptance to irritation and annoyance as the numbers increased relative to the size of the local population, until finally they resulted in antagonism between hosts and guests (see Allen, Long, Perdue, & Kisselbach, 1988; Boissevain, 1977; Williams, 1979). Host-guest relationships were also the focus of much of the early tourism research in sociology and anthropology (Cohen, 1979; MacCannell, 1976; Smith, 1989). For example, Rosenow and Pulsipher (1979) associated seasonal visitor pressure, adverse tourist behaviour, and environmental impacts with negative tourism outcomes; issues remarkably similar to those identified 40 years later as root causes for overtourism (Peeters et al., 2018).

From the 1980s onwards, this led to various conceptualisations of tourist pressure, and attempts to develop management solutions. Butler (1980) saw risks associated with destination growth as potentially leading to their decline, while UNWTO (1983) discussed the risk of destination saturation. Interrelated dimensions of carrying capacity were introduced by O'Reilly (1986), changing the view from assessments of pressure on a system to the pressure a system may tolerate. In the 1990s, more systematic analyses of mass tourism phenomena began to emerge. Considerable research focused on the situation in the Mediterranean, where economics of scale had turned sun and sea experiences into “widely affordable forms of mass consumption” since the 1950s (Bramwell, 2004: 1–2). Tourism growth was seen as a way of diversification, and usually welcomed by residents, even when negative developments related to coastal environments, unregistered labour, and seasonal and spatial concentration became evident. However, with continued growth, views changed (Bramwell, 2003), also as a result of the concentration of tourism developments in narrow strips of coastal land in specific areas (Ioannides & Holcomb, 2001; Jordan, 2000). Since the early 1990s, this sparked public protests against tourism (Boissevain, 1996a, Boissevain, 1996b; Boissevain & Theuma, 1998) and prompted authorities to empirically investigate resident perceptions (Bramwell, 2003). “Overtourism”, if defined as a form of public protest by residents, is thus a phenomenon that has existed for at least 25 years (Capocchi, Vallone, Amaduzzi, & Pierotti, 2019; Milano, Novelli, & Cheer, 2019). Management approaches have been developed for equally long periods of time (e.g. Cooke, 1982; McCool, 1994).

In recent decades, research has highlighted complexities of tourist pressure in the context of “crowding”. Studies have shown that perceptions of tourism are related to visitor density; yet, tourist “pressure” is a psychological construct more than a measurable reality (Neuts, Nijkamp, & Van Leeuwen, 2012). It is thus closely linked to individual perceptions (Bell, Needham, & Szuster, 2011; Navarro Jurado, Damian, & Fernández-Morales, 2013), including motivations (Alazaizeh, Hallo, Backman, Norman, & Vogel, 2016; Marin, Newman, Manning, Vaske, & Stack, 2011). Some research has shown that perceptions of visitor pressure are associated with nationality and cultural backgrounds (Jin, Hu, & Kavan, 2016; Li, Zhang, Nian, & Zhang, 2017). Other influential factors include personal and situational characteristics, such as socio-demographics including, education, age and gender (Rasoolimanesh, Jaafar, Marzuki, & Abdullah, 2017; Zehrer & Raich, 2016); environmental characteristics, and activity types (Klanjšček, Geček, Marn, Legović, & Klanjšček, 2018; Manning, Valliere, Minteer, Wang, & Jacobi, 2000; Tarrant, Cordell, & Kibler, 1997). Yet further studies have noted the degree of interaction with local communities as an influence on perceptions of crowding (Neuts & Nijkamp, 2012; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017).

While much of the research in this area has studied visitor density from the perception of tourists, “overtourism” is a concept explicitly linked to the perspective of residents (Koens, Postma, & Papp, 2018). Research shows that crowding leads to changes in the perception of the liveability, desirability or economic viability of a place (e.g. Bellini, Go, & Pasquinelli, 2017; Lawson, Williams, Young, & Cossens, 1998). Overtourism has been mostly discussed in urban contexts (Koens et al., 2018), but such perceptions can also be expressed in other spaces, such as, parks, beaches or attractions, often seasonally (e.g. Milano, Cheer, & Novelli, 2019). Negative outcomes can be related to social, environmental or economic issues (Weber et al., 2017). For instance, negative consequences include congestion and overuse of infrastructure (from roads to toilets), the privatisation of public places, the loss of purchasing power, high tourist to resident ratios, commercial gentrification, antisocial behaviour, and environmental deterioration (air pollution, waste) (Koens et al., 2018; Peeters et al., 2018).

The types of effects outlined in recent reports (cf Peeters et al., 2018) also reveal that many of the issues are linked in causal chains. For instance, the rapid expansion of peer to peer accommodation platforms such as AirBnB in virtually all world cities has reduced access to residential housing, leading to increased pressure on rental markets, and simultaneously changing the proportion of tourists in the local population (Koens et al., 2018; Lee, 2016). The reason for these developments is property speculators and developers seeking to maximize income from their properties, and city councils failing to regulate housing markets (Peeters et al., 2018). The discussion of such causalities helps to distinguish the development of tourism in destinations, from their root causes, as well as the role (and failure) of governance and destination managers in resolving overtourism conflicts (Butler & Dodds, 2019; Koens et al., 2018).

Method

This paper takes a conceptual approach to overtourism. This posits the issue as a psychological reaction of residents to tourist pressure, in which place-person interrelationships are affected and damaged, triggering different types of emotional and behavioural responses. Conceptual research encompasses a wide range of approaches, definitions and meanings, making attempts to contrast it with empirical approaches overly reductionist and simplistic (for a review of conceptual research, see Xin, Tribe, & Chambers, 2013). The term ‘conceptualisation’ is used in this paper to reinterpret, clarify and integrate concepts from a range of different disciplines, and to formally and systematically analyse those concepts. Thus, we take a combined empirical and philosophical route to examine “reality as well as the analytic practice and the practical ideas that have emerged from it” (Xin et al., 2013: 72), in this case the place/person relationships that describe attitude shifts due to overtourism. This approach involves a thorough review of relevant knowledge about concepts, their origins and historical development, as well as clarifying their meaning to create a conceptual framework that provides a holistic interpretation of the phenomenon. A similar approach is taken by Pung, Gnoth, and Del Chiappa (2020), in their conceptual research on tourist transformation. Through hermeneutical lens, this paper analyzed streams of associated key concepts to develop an holistic model of transformation processes.

This paper synthesizes concepts on the basis of a literature review of articles on crowding and tourist pressure, and the use of social psychology theory to discuss the implications of place change. This is not novel per se (Devine-Wright, 2009), as interrelationships of place attachment and place satisfaction in tourism contexts have been confirmed in earlier studies (Dredge, 2010; Ramkissoon, Weiler, & Smith, 2012). Yet, the use of social psychological theory to interpret reactions to place change in this paper is different from earlier studies because of its context (tourist pressure from a resident perspective) and focus (emotions constituting resistance). The paper also discusses reactions to on-going place change, rather than reflections on anticipated developments that may include forms of NIMBYism (Devine-Wright, 2009), i.e., views on (future) change in the tourism system (Dredge, 2010).

Resistance to change may be explained out of the lack of institutional form, such as opportunities for residents to participate in planning processes. Newspapers often present tourism ‘resistance’ as a form of emotional response, however, triggered by notions of place change and ownership, and the purpose of place-protective action. This underlines the importance of a psychological approach to ‘overtourism’ that considers meanings and emotions (Devine-Wright, 2009). Place attachment, Ramkissoon et al. (2013: 260) affirm, is an “emotional bond people share with a place”, and place change will result in an issue-attention cycle involving awareness, interpretation, evaluation, coping and action (Devine-Wright, 2009). This paper consequently argues that in order to understand overtourism, it is necessary to understand agency (the forms and expressions of resistance) in the context of the meanings associated with location, and the emotional responses to change. For this purpose, the paper discusses social psychology theories related to place, and conceptualizes responses to change as overtourism outcomes.

Social psychological theory and resident perceptions of tourism

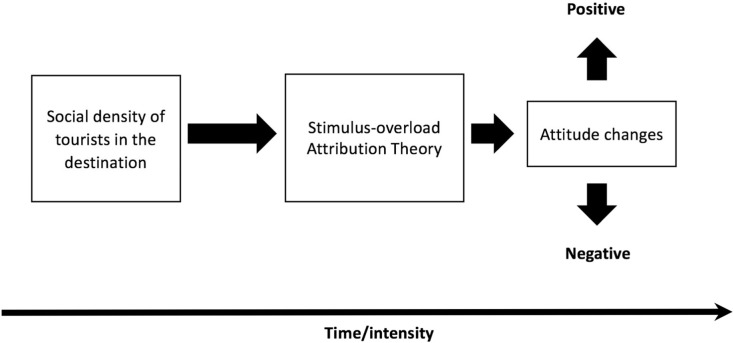

“Overtourism” has been defined as a situation in which a share of a local population feels that local ways of life or quality of life is diminished as a result of tourism, leading to forms of resistance or protest directed at tourism, tourists, policymakers or economic stakeholders (UNWTO, 2018). Relationships between place and person have been noted over many decades and studied on the basis of different theories. Studies in the 1970s discussed negative emotions (Stokols, 1972), also on the basis of psychological theories, such as Social Exchange Theory (Emerson, 1976). A simplified representation of these interrelationships is presented in Fig. 1 . This conceptualisation is based on the presumption that overtourism is essentially about visitor numbers (social density) in relation to space, the (speed of) change linked to outcomes that may be social, cultural, economic and/or environmental in character (intensity over time), and the socio-psychological responses among residents triggered by these changes (stimulus overload, attribution, control, arousal). The conceptualization acknowledges that the presence of tourists is not per se negative, and can also be perceived positively.

Fig. 1.

A simplified model of resident reactions to the presence of tourists.

While resident perceptions have been assessed in different ways, a key challenge in the context of overtourism is to understand how changes in attitudes transmit and how they are triggered. For this purpose, it is important to distinguish overtourism from crowding. Early tourism studies extensively discussed crowding as a phenomenon representing negative views of tourists on tourists (Alegre & Garau, 2010; Andereck & Becker, 1993; Shelby, Vaske, & Heberlein, 1989; Vaske & Shelby, 2008). Overtourism commonly refers to resident viewpoints of tourism, with antecedents in the perceptions literature (Allen et al., 1988; Ap, 1992; Ap & Crompton, 1993; Sheldon & Var, 1984). What these studies have in common is that they describe attitudes towards visitors.

In a recent study, Steen Jacobsen, Iversen, and Hem (2019) noted that links between place and psychology have relevance for understanding antecedents to social attitudes. Their study related notions of density of people within space to psychological responses. “Perceived social density” can activate higher states of arousal, leading to either positive or negative outcomes, and goal directed behaviours such as negative avoidance or positive approach (Stokols, 1972). Humans might actively seek out crowds in certain contexts but find them highly stressful in other environments. Steen Jacobsen and colleagues also relate these cognitive and affective responses to concepts of ‘personal space’, noting that perceptions of social density can trigger the human defence system, including fear and aversion (Andereck, 1997). Yet, there is a distinct conceptual difference between social density (closeness to other people) and physical density (restricted movement), as highlighted by Kim, Lee and Sirgy (2016).

Allport (1935: 810) defines attitude as “a mental or neural state of readiness, organized through experience, exerting a directive or dynamic influence upon the individual's response to all objects and situations with which it is related”. Thus, attitudes change over time, as a response to developments in the socio-economic and environmental fabric of a local community reach a ‘tipping point’, where attitudes to tourism become predominantly negative. Subsequently, such negative views may spread to larger parts of the population (cf. Allport, 1954).

Two recent review articles have examined the literature on resident's attitudes towards tourism and it's impacts. García et al. (2015) identified that research on resident's attitudes to tourism has been ongoing since the 1960's and has been undertaken across global contexts. They highlighted some common findings: that resident attitudes are linked to economic, social and environmental changes brought about by the development of tourism (cf Andereck, Valentine, Knopf, & Vogt, 2005). Of the huge range in research undertaken on the sociocultural impacts of tourism, García et al. (2015) point to more contradictory results, where some positive aspects were often counterbalanced by negative views on the social cost (see for example Teye, Sönmez, & Sirakaya, 2002). García et al. (2015) emphasize the methodological homogeneity of much research on resident attitudes, mostly based on quantitative, cross-sectional surveys using Likert scales, with fewer devoted to developing theory. In their review, the range of theories includes dependency theory, compensation theory in addition to the predominant social exchange theory model and specific ones developed to explain resident attitudes (such as Gursoy, Jurowski, & Uysal, 2002). Yet these have all proven to lack effectiveness in explaining changes in resident attitudes, something bemoaned almost thirty years ago by Ap (1992).

In the second review, McKercher et al. (2015) identified and analyzed 160 papers on community attitudes to tourism, concluding that negative perceptions of place change were far more likely than positive resulting from tourism. Where tourism was perceived negatively, this was a result of “diminished place attachment, loss of distinctiveness, continuity, self-esteem or self-efficacy” (ibid.: 58). These findings showed remarkable similarities to the findings of recent research on overtourism, that negative perceptions were linked to various forms of disruptions or competition over scarce resources (cf. Koens et a. 2018; Peeters et al., 2018).

Steen Jacobsen et al. (2019) identified stimulus-overload theory (Schmidt & Keating, 1979) as a key conceptual basis from which to examine these changing place/person relationships. These determine the changes in attitudes brought about by the changes in social density of tourists in places. Stimulus overload theory is based on the idea that the numbers, their presence in the space and their diversity can lead to psychological stress causing affective or behavioural responses (Schmidt & Keating, 1979). Steen Jacobsen et al. (2019) measured approach/avoidance reactions grounded in stimulus-overload theory, in the context of cruise ship visitation. Avoidance reactions may be expected when too many stimuli over a rapid rate of time exceed the individual's tolerance levels. This leads to a perceived loss of control and negative attitudes to tourism. This research is particularly suited to understanding the crowding perceptions of tourists within visitor site spaces, i.e. processes that are fundamentally different from other tourism outcomes, such as longer-term resident displacement as a result of AirBnB expansion in residential areas. The theory of stimulus-overload and perceived loss of control can also be usefully applied to explain changes in resident attitudes.

Responses among the local community to overtourism might be triggered when local residents perceive changes to be out of their control. It has been long recognized that people like to feel a sense of control over their environment, indeed it is perhaps one of the most fundamental human needs (Skinner, 1996). A perceived loss of control has been linked to high social density environments, leading to compensatory or control restoring behavioural responses among consumers for example (Consiglio, De Angelis, & Costabile, 2018). In tourism contexts, perceived loss of control may become an issue when tourist numbers are highly unstable. A situation of loss of control could emerge over the course of a tourist season, when large volumes of tourists are sustained over a period of weeks or months, or at a sudden influx associated with arrivals from cruise ships at certain times of the day. Residents may not feel willing to relocate due to feelings of place attachment, a sense of belonging or an inability to move for personal, situational reasons such as family ties. As Baumeister and Leary (1995: 522) highlighted, humans have a fundamental need to belong, and “the desire for interpersonal attachment may well be one of the most far-reaching and integrative constructs […] to understand human nature”.

Another relevant theory that connects these issues is attribution theory (Heider, 1958). Attribution theory is concerned with the perceived causes of one's own or other people's behaviour, based on the idea that people seek to make causal attributions in order to understand and control their environment. Attribution is a cognitive process, whereby an inference is made about the cause of an actor's behaviour. Kelley (1973) developed the theory in a systematic way based on the principle of covariance. This refers to the necessity to distinguish between three possible types of causal inferences; in the case of overtourism reactions, these would include the tourists, their actions/behaviour in the destination and the effects on place. People interpret behaviour in terms of its causes and their interpretations have an influence on reactions to this behaviour (Kelley & Michela, 1980). Considering that overtourism causes increased stimulus-overload, and higher states of arousal, leading to perceived loss of control, the emotion a person will experience upon his arousal will be linked to the explanation the person has for it. Attribution theory could have a role to play in understanding how changes in resident attitudes to tourists can be linked to the ascriptions made to the behaviours of tourists in the space or ascribe problems to tourists: Local residents will associate crowding, high rents, displacement, pressure on public transport and other infrastructure, to the presence of tourists. This is a psychological state based on perceptions of the behaviours of others in space, which adds a different perspective to other approaches, such as stimulus-overload theory.

Accordingly, people (residents) make judgments on the behaviours of people that are consistent with expectations for those behaviours. Thus, they may judge some outcomes can be attributed to situational constraints, the external stimulus, or other factors, and not the person(s) doing the behaviour. Alternatively, people may judge outcomes as departing from what is expected, and therefore attributable to the characteristics, or traits of the person(s) doing the behaviour. This is important since tourist behaviours are often perceived pejoratively (cf McCabe, 2005), and consistent with ‘out-group’ characteristics (McCabe & Stokoe, 2004), rather than as being related to behaviours or characteristics people might ascribe to themselves. While attribution theory has been raised in relation to tourist motivation and expectancy formation as well as satisfaction with experiences (Gnoth, 1997; Juvan & Dolnicar, 2014), it has yet to be applied in relation to residents' reactions to tourism, and in the context of place.

A multidimensional conceptualisation of place/person interactions

A place has essential features (Gieryn, 2000: 464–465): it is a “unique spot”, and even though its boundaries are elastic, it is a locality that is mostly understood in distinction to “near and far”, this is, in comparison. Place also has “physicality”, in that it is characterized by its built or natural environment, as well as specific social and economic structures. Finally, a place carries meaning and value, in that it is narrated, felt or imagined. Place-making becomes possible on the basis of these dimensions, including processes of identification, interpretation and remembering, which create proximity, interaction and community. As this definition of place suggests, physical, social and psychological dimensions are interrelated and interwoven.

It follows that a place has a past and a present that create its social value (Tuan, 1975), and even though it is “malleable over time, and inevitably contested” (Gieryn, 2000: 465), it also has stability. Even though a large share of humanity is on the move in the age of globalization, residents continue to dwell in specific places for prolonged periods, and they constitute the customs, cuisine, believes, ideas, or other forms of intellectual or material development that characterize a place (Glennie & Thrift, 1993). These interrelationships of humans with their environment have received much attention in the literature, originally a research field in anthropology (e.g. Ingold, 2000), and advanced in environmental psychology (Lewicka, 2005). Bonds with a place have been discussed as “sense of place”, “rootedness”, “place attachment” and “place identity” (e.g. Bonaiuto, 2004; Jorgensen and Stedman, 2001, Jorgensen and Stedman, 2006; Lewicka, 2005; Low & Altman, 1992; McAndrew, 1998; Proshansky, Fabian, & Kaminoff, 1983; Stedman, 2002, Stedman, 2003). The understanding of a place is multidimensional, in that it includes aspects of “beliefs, emotions and behavioural commitments” to a locality (Jorgensen & Stedman, 2006: 316), or what Lew (2017: 449) summarized as “how a culture group imprints its values, perceptions, memories, and traditions on a landscape and gives meaning to geographic space”.

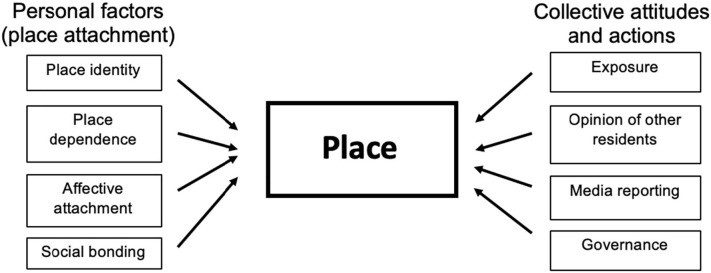

In this paper, the wider term place attachment is used to describe perspectives on place, reflected in dimensions of place identity, place dependence, affective attachment, and social bonding. Together, these represent three elements of attitudes towards a place, i.e. beliefs and ideas (cognitive), feelings or emotions (affective) and tendencies to act in specific ways (conative) in regard to place (Hidalgo & Hernández, 2001; Jorgensen & Stedman, 2001).

“Attachment” is a term that was originally introduced in psychology to describe mother-child relationships (Bowlby, 1958). In the context of human-environmental bonds, it describes the strength of an association between an individual and a place (Stokoe & Shumaker, 1981), and specifically emotional (affective) associations with place (Jorgensen & Stedman, 2001). Place attachment develops out of personal experiences, i.e. place memories, which form and reflect the basis for place attachment (Chen & Dwyer, 2018). Affective attachment is an emotional dimension of place that also includes social networks, reflected in a social dimension of bonding that has great importance for feelings of social belonging (Gieryn, 2000). Where such feelings are jeopardized, this affects willingness to stay in a place. This may for instance reverberate in Putnam's (2000) finding that where social structures are in decline, people are more likely to migrate or to become more mobile. Tourism can disrupt place attachment. McCool and Martin (1994) found, for example, that length of residency and place attachment are interrelated; and that tourism development reduces the average tenure of residents in communities. Residents feeling to have an emotional right to place are also more likely to consider outsiders' claims of place as illegitimate (McCabe & Stokoe, 2004).

Place identity, as a cognitive dimension of place attachment, refers to beliefs, ideas or thoughts about place in relation to Self, embracing elements of continuity (the characteristics of a place) and uniqueness (the distinctiveness of a place) (Lewicka, 2008). Place identity is consequently an outcome of “memories, ideas, feelings, attitudes, values, preferences, meanings and conceptions of behaviour” (Proshansky et al., 1983: 59). In reference to Urry (1995), it may be added that place identity also evolves in juxtaposition to an imagined or perceived Other, through imaginative, virtual or corporeal travel. For local residents, place identity is thus also linked to their own tourist experiences, watching TV, or the observation of tourists and their behaviours. Overall, place identity is characterized by at least four elements (Breakwell, 1986, Breakwell, 1992), i.e. distinctiveness (the uniqueness of a place to a person), continuity (the persistence of feelings for a place), self-esteem (personal worth or social value in relation to place), and self-efficacy (having goals in relation to place that can be achieved).

Place dependence, as a conative dimension of place attachment, refers to the propensity to act in certain, place-specific ways. The concept was originally used by Stokols and Shumaker (1982) to describe an individual's perception of being strongly attached to a place, also because of specific activities, though Stokols and Shumaker described this as “place specificity” (ibid.: 157). Importantly, Stokols and Shumaker (1982) linked place dependence to activities carried out in a location, and decisions to move from an area to mental health and stress: A place “congruent with one's needs” (ibid.: 167) was found to be associated with better health. This continues to be of relevance, because residents may, in extremis, be forced to leave an area because of tourism. Place dependence, as a conative dimension, consequently describes the disposition to act in a certain way in relation to a place confronted with tourism (see also Hammitt, Backlund, & Bixler, 2006).

Place attachment and its dimensions determine place satisfaction, which in the context of this paper describes the general attitude of residents to a place, including a sense of ownership and views regarding its ‘ideal’ states. In most destinations, tourism will have grown over time, and even have co-evolved with local communities. The presence of tourists or day visitors will consequently be part of place attitudes. Where more critical views on tourism emerge, this will be a result of change, i.e. developments interfering with place attachment (Shamai & Ilatov, 2005). Perceptions of undesirable developments will generally depend on personal factors, described by place attachment, as well as collective attitudes and actions, including the views of other residents, media reports, employment in tourism, or forms of governance and policy responses (Fig. 2 ). Change also includes a dimension of speed, i.e. the timeframes over which change occurs. For instance, seasonal tourist pressure, a significant new infrastructure (e.g., a large hotel), or other developments may have great relevance for place satisfaction.

Fig. 2.

Place-person interactions.

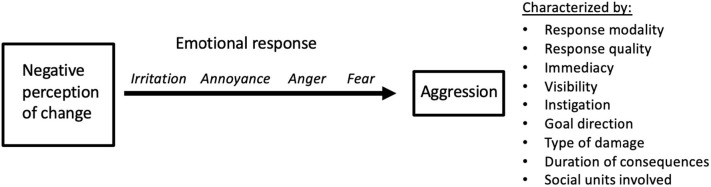

On the level of the individual, changes questioning place attachment are a potential threat to place satisfaction. When thresholds are exceeded, this may result in negative reactions to tourism, in which tourists are considered an out-group in juxtaposition to a resident in-group. Through forms of social categorization, identification and comparison, tourists may be more easily seen as invading a place, an effect that maybe reinforced through critical media reporting. As Bushman and Huesmann (2010: 839) outlined, a situation perceived as unpleasant will produce “primitive reaction tendencies (e.g. flight or fight)”. Such responses are stress-responsive and can be triggered by frustrations as well as more aversive stimuli. They are also dependent on the individual, i.e. personalities, values, or moods. Importantly, reactions will be emotional, and develop through various stages, such as irritation, annoyance, anger and fear (Fig. 3 ). Depending on an individual's emotional state, responses may be defensive (withdrawing, flight) or offensive (aggressive, fight).

Fig. 3.

Response to negative perceptions of change.

Emotional responses may serve various purposes, such as to escape from aversive situations, to release negative affective arousal, to resolve conflict, or to gain respect (e.g. Parrot, 2001). Along the distinction of flight or fight, flight responses may include avoidance of tourists – for instance, by leaving a certain area during a seasonal peak or specific event. Flight may also be involuntary, as in the case of residents being forced to leave an area as a result of rising rents caused by a growing number of commercially rented AirBnB properties. Where the reaction is to fight, this represents a form of aggression, i.e. “a response that delivers noxious stimuli to another organism” (Buss, 1961: 1). In a social system, aggression may be considered as a violation of social norms that depends on cognitive interpretation as well as the presence of aversive cues (Berkowitz, 1993). Taken to its extreme, aggression can involve violence, defined as “the infliction of intense force upon persons or property for the purposes of destruction, punishment, or control” (Geen, 1995: 669).

The character of emotional responses and reactions can be defined in various dimensions. Krahé (2001) suggested a typology of aggressive behaviour that embraces response modality (verbal versus physical); response quality (action versus failure to act); immediacy (direct versus indirect); visibility (overt versus covert); instigation (unprovoked versus retaliative); goal direction (hostile versus instrumental); type of damage (physical versus psychological); duration of consequences (transient versus long-term); social units involved (individuals versus groups). These response characteristics and dimensions, which may often represent a continuum rather than a dichotomy, can be used to structure specific reactions to overtourism (Table 1 ; see also Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Overtourism response characteristics.

| Response characteristic | Dimension | |

|---|---|---|

| Response quality | Failure to act | Action |

| Response modality | Verbal | Physical |

| Immediacy | Direct | Indirect |

| Visibility | Overt | Covert |

| Instigation | Unprovoked | Retaliative |

| Goal direction | Hostile | Instrumental |

| Type of damage | Physical | Psychological |

| Duration of consequences | Transient | Long-term |

| Social units involved | Individuals | Groups |

Source: based on Krahé (2001).

For example, the case of a resident berating a tourist in response to littering represents an action (response quality), is verbal (response modality), direct (immediacy), overt (visibility), retaliative (instigation), hostile (goal direction), psychological (type of damage), transient (duration of consequences) and individual (social unit involved). In comparison, the founding of an anti-tourism organisation represents an action (response quality), is verbal (response modality), indirect (immediacy), overt (visibility), retaliative (instigation), instrumental (goal direction), psychological (type of damage), long-term (duration of consequences) and group-based (social unit involved). Resident responses to overtourism may be organised on the basis of these response characteristics.

Responses to overtourism

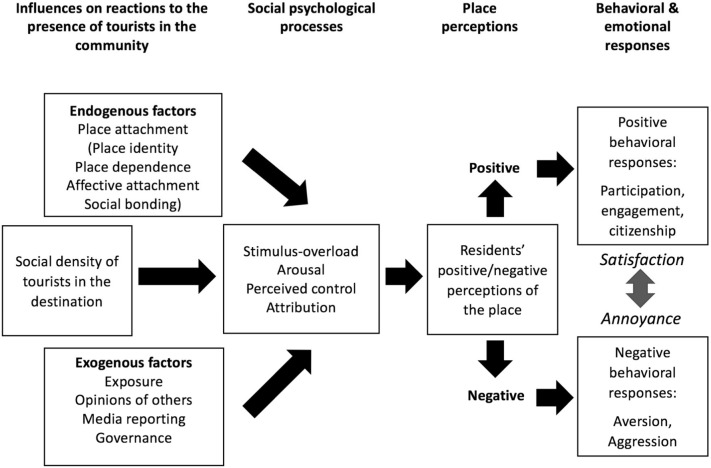

As the preceding sections have illustrated, overtourism is linked to perceived social density and residents' changing attitudes towards the presence of tourists. Tourism, through a wide range of interrelated impacts, can interfere with notions of desirable place states, and invoke questions of place ownership (McKercher et al., 2015). These interrelationships can be conceptualized in a social-psychological overtourism model (Fig. 4 ). The model suggests that perceived social density as an outcome of the number of people in a given location can trigger crowding experiences (Stokols, 1972) and is in itself an important factor in stimulus-overload (Steen Jacobsen et al., 2019). Place attachment, as a form of place sense making and belonging, is important in determining overtourism outcomes. Where place attachment is disrupted, attitudes change from positive (or neutral) to negative. Factors influencing perceptions include, for instance, media reporting or policy responses. These affect perceived control. Together, these dimensions will determine perceptions of overtourism, emotional responses, and behavioural reactions including participation and engagement (positive) or aversion and aggression (negative). As the model suggests, tourism will not per se have negative outcomes; rather, it is possible that tourism can positively reinforce perceptions of a place. This, however, is less likely in scenarios where visitor numbers are high in relation to the local population, or concentrated in small areas, where tourist behaviours interfere negatively with local customs and social norms, and where fewer people profit from tourism developments.

Fig. 4.

A social psychology conceptualisation of overtourism.

In summary, the social psychology conceptualisation model of overtourism proposes that reactions to environmental and social change should be interpreted as social psychological processes that reflect interferences with place perceptions, leading to behavioural and emotional responses. This is consistent with previous models discussed on residents' perception and behaviours regarding tourism development, but with stronger theoretical implications. For instance, Jurowski, Uysal, and Williams (1997) proposed a model of reactions to environmental change (including the evaluation of economic gain, resource use) and linkages to social psychology processes (such as community attachment and eco-centric attitudes), which then leads to perceived impacts of tourism and behaviours such as support for tourism. Similar models can also be found in the studies by Choi and Murray (2010) or Vargas-Sánchez, Porras-Bueno and Plaza-Mejía (2011). A limitation of these models is that they focus solely on the cognitive aspect of the social psychology, overlooking emotional responses and their relevance for observed outcomes. Yet, the importance of emotions for behaviour is widely acknowledged in social psychology (e.g. Dasborough, 2006), marketing (e.g. Watson & Spence, 2007), and tourism (Chang, Gibson, & Sisson, 2014; Palmer, Koenig-Lewis, & Jones, 2013).

The proposed conceptualisation in this paper provides an extended context for the discussion of overtourism. Importantly, it suggests that to ignore resident stress responses is equal to accepting more violent forms of anti-tourism sentiment in the longer term. While the paper thus confirms some of the place-person interrelationships outlined by McKercher et al. (2015) or Steen Jacobsen et al. (2019), it also highlights social psychological complexities, and the importance of considering responses to overtourism as emotionally accentuated outcomes of changes in place perceptions. The results require a macro-level consideration of limits to tourism growth, i.e. strategies rejected by UNWTO (2018) and unconsidered in tourism reports (World Economic Forum, 2017; WTTC & McKinsey 2017).

Conclusions

Academic consideration of the impact of tourism development on host communities is one of the most traditional and foundational areas of tourism research. With notions of overtourism, it has reached a new type of audience and taken on a heightened level of significance to denote significant changes in the collective attitudes of a community towards the presence of tourists. There is an inadequate understanding of the social and psychological processes underlying perceptions of and attitudes towards overtourism among local communities.

This paper has conceptualized the processes behind understandings of overtourism; a phenomenon that might be triggered when local residents perceive social, economic or environmental changes brought about by increased social density of visitors in localities, to represent a significant, negative change, causing stimulus overload, arousal, and negative affect. Residents will feel that they have no internal locus of control over tourism or tourist activity, and psychologically, a decline in place satisfaction will foster anti-tourism sentiment. Where such interferences reach thresholds, this will trigger avoidance strategies or forms of aggression.

Existing research has generally highlighted that tourist arrival growth as well as tourist density are important factors determining overtourism outcomes. Both represent interferences in person-place interrelationships, expressed in terms of the speed and character of change in a given location, and underline the need to reconsider volume growth tourism models. As this research contends, a continuing failure to address the socio-psychological consequences on resident communities of burgeoning tourist demand at the macro and local levels will produce negative social outcomes; to the point where municipal governments are toppled (Russo & Scarnato, 2018).

The discussion of place attachment implications of tourist pressure also calls for an ethnographic research agenda, as many interrelationships remain insufficiently understood. As tourism industry and advocacy platforms currently chart the trajectories for a return to a post-pandemic business-as-usual scenario, understanding anti-tourism sentiment gains importance in order to avoid the mistakes of the past. Most certainly, strategies to avoid overtourism phenomena will have to be sought outside UNWTO's (2018) ‘disperse and distribute’.

Biographies

Stefan Gössling is a professor at the Department of Service Management, Lund University, and the School of Business and Economics, Linnaeus University, Sweden. He is also the research co-ordinator at the Western Norway Research Institute's Research Centre for Sustainable Tourism. His major interest is the sustainability of tourism and transport. Email: stefan.gossling@lnu.se

Scott McCabe is a professor of Tourism Management/Marketing at Nottingham University Business School, and Associate Dean for Research. His research interests are on tourist experience, consumer behaviour and social tourism. His research takes an interdisciplinary perspective spanning sociology and psychology, and particularly socio-linguistics. He is Editor in co-Chief of Annals of Tourism Research.

Ning (Chris) Chen Ph.D. is Senior Lecturer at the Department of Management, Marketing & Entrepreneurship, University of Canterbury, New Zealand; Research Fellow at the Tsinghua University Center for Development of Sports Industry, Tsinghua University, China. His research interests are in place attachment, resident/tourist psychology & behaviour, destination branding, and sports marketing.

Associate editor: Juergen Gnoth

References

- Alazaizeh M.M., Hallo J.C., Backman S.J., Norman W.C., Vogel M.A. Crowding standards at Petra Archaeological Park: A comparative study of McKercher's five types of heritage tourists. Journal of Heritage Tourism. 2016;11(4):364–381. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre J., Garau J. Tourist satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Annals of Tourism Research. 2010;37(1):52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Allen L.R., Long P.T., Perdue R.R., Kisselbach S. The impact of tourism development on residents' perceptions of community life. Journal of Travel Research. 1988;27(1):16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Allport G.W. Attitudes. In: Murchison C., editor. A handbook for social psychology. Worcester; Clark University Press: 1935. pp. 798–844. [Google Scholar]

- Allport G.W. Addison-Wesley; New York: 1954. The nature of prejudice. [Google Scholar]

- Andereck K.L. Territorial functioning in a tourism setting. Annals of Tourism Research. 1997;24(3):706–720. [Google Scholar]

- Andereck K.L., Becker R.H. Perceptions of carry-over crowding in recreation environments. Leisure Sciences. 1993;15(1):25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Andereck K.L., Valentine K.M., Knopf R.C., Vogt C.A. Residents' perceptions of community tourism impact. Annals of Tourism Research. 2005;32(4):1056–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Ap J. Residents' perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research. 1992;19(4):665–690. [Google Scholar]

- Ap J., Crompton J.L. Residents' strategies for responding to tourism impacts. Journal of Travel Research. 1993;32(1):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R.F., Leary M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C.M., Needham M.D., Szuster B.W. Congruence among encounters, norms, crowding, and management in a marine protected area. Environmental Management. 2011;48(3):499–513. doi: 10.1007/s00267-011-9709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini N., Go F.M., Pasquinelli C. Urban tourism and city development: Notes for an integrated policy agenda. In: Bellini N., Pasquinelli C., editors. Tourism in the city: Towards an integrative agenda on urban tourism. Springer International Publishing; Switzerland: 2017. pp. 333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. Mcgraw-Hill Book Company; Philadelphia, PA: 1993. Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. [Google Scholar]

- Boissevain J. Tourism and development in Malta. Development and Change. 1977;8(4):523–538. [Google Scholar]

- Boissevain J. Vol. 1. Berghahn Books; Providence, Oxford: 1996. Coping with tourists: European reactions to mass tourism. [Google Scholar]

- Boissevain J. ‘But we live here!’: Perspectives on cultural tourism in Malta. In: Briguglio L., Butler R., Harrison D., Filho W., editors. Sustainable tourism in islands and small states: Case studies. Pinter; London: 1996. pp. 220–240. [Google Scholar]

- Boissevain J., Theuma N. Contested space. Planners, tourists, developers and environmentalists in Malta. In: Abram S., Waldren J., editors. Anthropological perspectives on local development. Routledge; London: 1998. pp. 96–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaiuto M. Residential satisfaction and perceived urban quality. Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology. 2004;3:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The nature of the child's tie to his mother. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 1958;XXXIX:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell B. Maltese responses to tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 2003;30(3):581–605. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell B., editor. Coastal mass tourism: Diversification and sustainable development in Southern Europe. Vol. 12. Channel View Publications; Bristol: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Breakwell G.M. Methuen; London: 1986. Coping with threatened identity. [Google Scholar]

- Breakwell G.M. Surrey University Press; Surrey: 1992. Social psychology of identity and the self-concept. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman B.J., Huesmann R. Aggression. In: Fiske S.T., Gilbert D.T., Lindzey G., editors. Handbook of social psychology. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2010. pp. 833–863. [Google Scholar]

- Buss A.H. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 1961. The psychology of aggression. [Google Scholar]

- Butler R.W. The social implications of tourist developments. Annals of Tourism Research. 1974;2(2):100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Butler R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien. 1980;24(1):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Butler R.W., Dodds R., editors. Overtourism: Issues, realities and solutions. De Gruyter; Berlin: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Capocchi A., Vallone C., Amaduzzi A., Pierotti M. Is ‘overtourism’ a new issue in tourism development or just a new term for an already known phenomenon? Current Issues in Tourism. 2019:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chang S., Gibson H., Sisson L. The loyalty process of residents and tourists in the festival context. Current Issues in Tourism. 2014;17(9):783–799. [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Dwyer L. Residents' place satisfaction and place attachment on destination brand-building behaviors: Conceptual and empirical differentiation. Journal of Travel Research. 2018;57(8):1026–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.C., Murray I. Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2010;18(4):575–594. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E. Rethinking the sociology of tourism. Annals of tourism research. 1979;6(1):18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Colomb C., Novy J., editors. Protest and resistance in the tourist city. Routledge; London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Consiglio I., De Angelis M., Costabile M. The effect of social density on word of mouth. Journal of Consumer Research. 2018;45(3):511–528. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke K. Guidelines for socially appropriate tourism development in British Columbia. Journal of Travel Research. 1982;21:22–28. summer. [Google Scholar]

- Dasborough M.T. Cognitive asymmetry in employee emotional reactions to leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly. 2006;17(2):163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Devine-Wright P. Rethinking NIMBYism: The role of place attachment and place identity in explaining place-protective action. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 2009;19(6):426–441. [Google Scholar]

- Doxey G. Proceedings of the sixth travel and tourism research association (TTRA) annual conference. 1975. A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants: Methodology and research inferences; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Dredge D. Place change and tourism development conflict: Evaluating public interest. Tourism Management. 2010;31(1):104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R.M. Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology. 1976;2(1):335–362. [Google Scholar]

- Füller H., Michel B. ‘Stop being a tourist!’ New dynamics of urban tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2014;38(4):1304–1318. [Google Scholar]

- García F.A., Vázquez A.B., Macías R.C. Resident's attitudes towards the impacts of tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2015;13:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Geen R.G. Cole Publishing; Belmont, CA: 1995. Human motivation: A social psychological approach. [Google Scholar]

- Gieryn T. A space for place in sociology. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:463–496. [Google Scholar]

- Glennie P.D., Thrift N.J. Modern consumption: Theorising commodities and consumers. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. 1993;11(5):603–606. [Google Scholar]

- Gnoth J. Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Annals of Tourism Research. 1997;24(2):283–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gravari-Barbas M., Jacquot S. No conflict? Discourses and management of tourism-related tensions in Paris. In: Colomb C., Novy J., editors. Protest and resistance in the tourist city. Routledge; London: 2016. pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy D., Jurowski C., Uysal M. Resident attitudes. A structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research. 2002;29(1):79–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hammitt W.E., Backlund E.A., Bixler R.D. Place bonding for recreation places: Conceptual and empirical development. Leisure Studies. 2006;25(1):17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Haulot A. La Recherche d'un Equilibre; Verviers: Marabout SA: 1974. Tourisme et environnement. [Google Scholar]

- Heider F. John Wiley; New York: 1958. The psychology of interpersonal relations. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M.C., Hernández B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2001;21:273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold T. Routledge; London: 2000. The perception of the environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides D., Holcomb B. Raising the stakes: Implications of upmarket tourism policies in Cyprus and Malta. In: Ioannides D., Apostolopoulos Y., Sönmez S.F., editors. Mediterranean Islands and sustainable tourism development. Practices, management and policies. Continuum; London: 2001. pp. 234–258. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari J. Research and scholarship: The basis of tourism education. Journal of Tourism Studies. 1990;1:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q., Hu H., Kavan P. Factors influencing perceived crowding of tourists and sustainable tourism destination management. Sustainability. 2016;8(10):976–992. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan P. Restructuring Croatia's coastal resorts: Change, sustainable development and the incorporation of rural hinterlands. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2000;8(6):525–539. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen B.S., Stedman R.C. Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners attitudes toward their properties. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2001;21(3):233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen B.S., Stedman R.C. A comparative analysis of predictors of sense of place dimensions: Attachment to, dependence on, and identification with lakeshore properties. Journal of Environmental Management. 2006;79(3):316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurowski C., Uysal M., Williams D.R. A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. Journal of Travel Research. 1997;36(2):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Juvan E., Dolnicar S. The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 2014;48:76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley H.H. The processes of causal attribution. American Psychologist. 1973;28:107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley H.H., Michela J.L. Attribution theory and research. Annual Review of Psychology. 1980;31(1):457–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Lee C.-K., Sirgy M.J. Examining the differential impact of human crowding versus spatial crowding on visitor satisfaction at a festival. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 2016;33(3):293–312. [Google Scholar]

- Klanjšček J., Geček S., Marn N., Legović T., Klanjšček T. Predicting perceived level of disturbance of visitors due to crowding in protected areas. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koens K., Postma A., Papp B. Is Overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability. 2018;10(12):43–84. doi: 10.3390/su10124384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krahé B. Psychology Press; London and New York: 2001. The social psychology of aggression. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf J. Hallwag; Bern: 1975. Die Landschaftsfresser: Tourismus und Erholungslandschaft-Verderben oder Segen? [Google Scholar]

- Lawson R.W., Williams J., Young T.A.C.J., Cossens J. A comparison of residents' attitudes towards tourism in 10 New Zealand destinations. Tourism Management. 1998;19(3):247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. How Airbnb short-term rentals exacerbate Los Angeles's affordable housing crisis: Analysis and policy recommendations. Harvard Law & Policy Review. 2016;10:229–254. [Google Scholar]

- Lew A.A. Tourism planning and place making: Place-making or placemaking? Tourism Geographies. 2017;19(3):448–466. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka M. Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2005;25(4):381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka M. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2008;28(3):209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhang J., Nian S., Zhang H. Tourists' perceptions of crowding, attractiveness, and satisfaction: A second-order structural model. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research. 2017;22(12):1250–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Low S.M., Altman I. Springer; Berlin: 1992. Place attachment. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell D. Schocken Books; New York: 1976. The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. [Google Scholar]

- Manning R., Valliere W., Minteer B., Wang B., Jacobi C. Crowding in parks and outdoor recreation: A theoretical, empirical, and managerial analysis. Journal of Park Recreation Administration. 2000;18(4):57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Marin L.D., Newman P., Manning R., Vaske J.J., Stack D. Motivation and acceptability norms of human-caused sound in Muir Woods National Monument. Leisure Sciences. 2011;33(2):147–161. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew F.T. The measurement of ‘rootedness’ and the prediction of attachment to home-towns in college students. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1998;18(4):409–417. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. ‘Who is a tourist?’ A critical review. Tourist Studies. 2005;5(1):85–106. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S., Stokoe E.H. Place and identity in tourist accounts. Annals of Tourism Research. 2004;31(3):601–622. [Google Scholar]

- McCool S.F. Planning for sustainable nature dependent tourism development: The limits of acceptable change system. Tourism Recreation Research. 1994;19(2):51–55. [Google Scholar]

- McCool S.F., Martin S.R. Community attachment and attitudes toward tourism development. Journal of Travel Research. 1994;32(3):29–34. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher B., Wang D., Park E. Social impacts as a function of place change. Annals of Tourism Research. 2015;50:52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Milano C., Cheer J.M., Novelli M., editors. Overtourism: Excesses, discontents and measures in travel and tourism. CABI; London: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Milano C., Novelli M., Cheer J.M. Overtourism and tourismphobia: A journey through four decades of tourism development, planning and local concerns. Tourism Planning & Development. 2019;16(4):353–357. [Google Scholar]

- Muler Gonzalez V., Coromina L., Galí N. Overtourism: Residents' perceptions of tourism impact as an indicator of resident social carrying capacity-case study of a Spanish heritage town. Tourism Review. 2018;73(3):277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Jurado E., Damian I.M., Fernández-Morales A. Carrying capacity model applied in coastal destinations. Annals of Tourism Research. 2013;43:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuts B., Nijkamp P. Tourist crowding perception and acceptability in cities. Annals of Tourism Research. 2012;39(4):2133–2153. [Google Scholar]

- Neuts B., Nijkamp P., Van Leeuwen E. Crowding externalities from tourist use of urban space. Tourism Economics. 2012;18(3):649–670. doi: 10.5367/te.2012.0130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Novy J. The selling (out) of Berlin and the de-and re-politicization of urban tourism in Europe's ‘Capital of Cool’. In: Colomb C., Novy J., editors. Protest and resistance in the tourist city. Routledge; London: 2016. pp. 52–72. [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly A.M. Tourism carrying capacity: Concept and issues. Tourism Management. 1986;7(4):254–258. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A., Koenig-Lewis N., Jones L.E.M. The effects of residents' social identity and involvement on their advocacy of incoming tourism. Tourism Management. 2013;38:142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Parrot W. Psychology Press; Philadelphia: 2001. Emotions in Social Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters P., Gössling S., Klijs J., Milano C., Novelli M., Dijkmans C.…Postma A. Research for TRAN Committee - Overtourism: Impact and possible policy responses, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels. 2018. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/629184/IPOL_STU(2018)629184_EN.pdf Available from.

- Proshansky H.M., Fabian A.K., Kaminoff R. Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1983;3(1):57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pung J.M., Gnoth J., Del Chiappa G. Tourist transformation: Towards a conceptual model. Annals of Tourism Research. 2020;81 [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. Simon & Schuster; New York: 2000. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon H., Weiler B., Smith L.D.G. Place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2012;20(2):257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon H., Smith L.D.G., Weiler B. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tourism management. 2013;36:552–566. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh S.M., Jaafar M., Marzuki A., Abdullah S. Tourist's perceptions of crowding at recreational sites: The case of the Perhentian Islands. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Research. 2017;28(1):41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenow J.E., Pulsipher G.L. Century Three Press; Lincoln: 1979. Tourism, the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. [Google Scholar]

- Russo A.P., Scarnato A. “Barcelona in common”: A new urban regime for the 21st-century tourist city? Journal of Urban Affairs. 2018;40(4):455–474. [Google Scholar]

- Sans A.A., Russo A.P. The right to Gaudí: What can we learn from the commoning of Park Güell, Barcelona? In: Colomb C., Novy J., editors. Protest and resistance in the Tourist City. Routledge; London: 2016. pp. 247–263. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D., Keating J. Human crowding and personal control: An integration of the research. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:680–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin H., Sheeran P., Pilato M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management. 2018;9:374–376. [Google Scholar]

- Shamai S., Ilatov Z. Measuring sense of place: Methodological aspects. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Social Geografie. 2005;96(5):467–476. [Google Scholar]

- Shelby B., Vaske J., Heberlein T. Comparative analysis of crowding in multiple locations: Results from fifteen years of research. Leisure Sciences. 1989;11(4):269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon P.J., Var T. Resident attitudes to tourism in North Wales. Tourism Management. 1984;5(1):40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E.A. A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71(3):549–570. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith V.L., editor. Hosts and guests: The anthropology of tourism. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman R.C. Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environment and Behavior. 2002;34(5):561–581. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman R.C. Sense of place and forest science: Toward a program of quantitative research. Forest Science. 2003;49(6):822–829. [Google Scholar]

- Steen Jacobsen J.K., Iversen N.M., Hem L.E. Hotspot crowding and over-tourism: Antecedents of destination attractiveness. Annals of Tourism Research. 2019;76:53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe D., Shumaker S.A. People in places: A transactional view of settings. In: Harvey J.H., editor. Cognition, social behavior and the environment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale: 1981. pp. 441–488. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. On the distinction between density and crowding: Some implications for future research. Psychological Review. 1972;79(3):275–277. doi: 10.1037/h0032706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D., Shumaker S.A. The psychological context of residential mobility and well-being. Journal of Social Issues. 1982;38(3):149–171. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrant M.A., Cordell H.K., Kibler T.L. Measuring perceived crowding for high-density river recreation: The effects of situational conditions and personal factors. Leisure Sciences. 1997;19(2):97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Teye V., Sönmez S.F., Sirakaya E. Residents' attitudes toward tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research. 2002;29(3):668–688. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan Y.F. Place: An experiential perspective. Geographical Review. 1975;65(2):151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Turner L., Ash J. Constable Limited; London: 1975. The “golden hordes”: International tourism and the pleasure periphery. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . WTO; Madrid: 1983. Risks of saturation of tourist carrying capacity overload in holiday destinations. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . UNWTO; Madrid: 2018. Overtourism? Understanding and managing urban tourism growth beyond perceptions. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO Restarting Tourism. 2020. https://www.unwto.org/news/restarting-tourism Available.

- Urry J. Routledge; London: 1995. Consuming places. [Google Scholar]

- Usher L.E., Gómez E. Managing stoke: Crowding, conflicts, and coping among Virginia Beach surfers. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration. 2017;35(2):9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Sánchez A., Porras-Bueno N., de los Ángeles Plaza-Mejía M. Explaining residents' attitudes to tourism: Is a universal model possible? Annals of Tourism Research. 2011;38(2):460–480. [Google Scholar]

- Vaske J.J., Shelby L.B. Crowding as a descriptive indicator and an evaluative standard: Results from 30 years of research. Leisure Sciences. 2008;30(2):111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Vianello M. The No Grandi Navi campaign: Protests against cruise tourism in Venice. In: Colomb C., Novy J., editors. Protest and resistance in the tourist city. Routledge; London: 2016. pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Watson L., Spence M.T. Causes and consequences of emotions on consumer behaviour: A review and integrative cognitive appraisal theory. European Journal of Marketing. 2007;41(5/6):487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Weber F., Stettler J., Priskin J., Rosenberg-Taufer B., Ponnapureddy S., Fux S.…Barth M. Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts; Lucerne, Switzerland: 2017. Tourism destinations under pressure. Challenges and innovative solutions. [Google Scholar]

- Williams T.A. Impact of domestic tourism on host population. Tourism Recreation Research. 1979;4(2):15–21. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum Wish you weren't here: What can we do about over-tourism? 2017. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/09/what-can-we-do-about-overtourism (last accessed 29 March 2019)

- WTTC (World Travel & Tourism Council), McKinsey Coping with success: Managing overcrowding in tourism destinations. 2017. https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/policy-research/coping-with-success---managing-overcrowding-in-tourism-destinations-2017.pdf (last accessed 29 March 2019)

- Xin S., Tribe J., Chambers D. Conceptual research in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 2013;41:66–88. [Google Scholar]

- Young G. Penguin Books; Harmondsworth: 1973. Tourism: Blessing or blight? [Google Scholar]

- Zehrer A., Raich F. The impact of perceived crowding on customer satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2016;29:88–98. [Google Scholar]