Abstract

Background

This systematic review and meta-analysis searched, retrieved and synthesized the evidence as to whether preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy (p-EGD) should be routine before bariatric surgery (BS).

Methods

Databases searched for retrospective, prospective, and randomized (RCT) or quasi-RCT studies (01 January 2000–30 April 2019) of outcomes of routine p-EGD before BS. STROBE checklist assessed the quality of the studies. P-EGD findings were categorized: Group 0 (no abnormal findings); Group 1 (abnormal findings that do not necessitate changing the surgical approach or postponing surgery); Group 2 (abnormal findings that change the surgical approach or postpone surgery); and Group 3 (findings that signify absolute contraindications to surgery). We assessed data heterogeneity and publication bias. Random effect model was used.

Results

Twenty-five eligible studies were included (10,685 patients). Studies were heterogeneous, and there was publication bias. Group 0 comprised 5424 patients (56%, 95% CI: 45–67%); Group 1, 2064 patients (26%, 95% CI: 23–50%); Group 2, 1351 patients (16%, 95% CI: 11–21%); and Group 3 included 31 patients (0.4%, 95% CI: 0–1%).

Conclusion

For 82% of patients, routine p-EGD did not change surgical plan/ postpone surgery. For 16% of patients, p-EGD findings necessitated changing the surgical approach/ postponing surgery, but the proportion of postponements due to medical treatment of H Pylori as opposed to “necessary” substantial change in surgical approach is unclear. For 0.4% patients, p-EGD findings signified absolute contraindication to surgery. These findings invite a revisit to whether p-EGD should be routine before BS, and whether it is judicious to expose many obese patients to an invasive procedure that has potential risk and insufficient evidence of effectiveness. Further justification is required.

Keywords: Preoperative, Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Bariatric surgery

Introduction

There is a debate about the utility of routine preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy (p-EGD) screening of patients undergoing bariatric surgery (BS) [1, 2]. The European and Italian national recommendations advocate the use of presurgery upper gastrointestinal endoscopy together with multiple biopsies in the work-up of patients; conversely, the American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery only recommends it in selected cases with symptomatic gastric disease [3–5]. Generally, the question of routine p-EGD has many clinical implications and significant financial repercussions [1].

Some evidence supports routine p-EGD among patients undergoing BS. The reasons include the weak correlation between the patients’ symptoms and p-EGD findings, that p-EGD is convenient, safe, applied easily [6–8], and p-EGD findings may alter the management and hence eliminate the future development of gastric pathology [9], or detect asymptomatic benign or pre/malignant lesions. Missing asymptomatic lesions in some BS where the distal stomach and/or duodenum is rendered unreachable by esophagogastroduodenoscopy could lead to missing some lesions in the bypassed stomach that p-EGD could have discovered [10–16]. Some authors endorse that all BS patients have p-EGD, as after surgery, the endoscope may not reach the gastric/duodenal mucosa [17]. In agreement, others recommended that all BS patients should have upper gastrointestinal endoscopy [8]. For some procedures (e.g., laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and vertical banded gastroplasty), p-EGD could provide information that might influence the operative procedure, particularly due to upper gastrointestinal lesions that often require medical therapy [7, 18].

It remains contested whether routine p-EGD should be undertaken for all patients undergoing e.g., laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) [19]. Some authors support routine p-EGD in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms (symptomatic cases only) [3, 20, 21]. Others suggest a selective approach for asymptomatic cases, because of the weak clinical relevance of most lesions discovered on routine p-EGD, its cost, and invasiveness [22, 23]. Still, other research found that routine p-EGD in LSG might require further justification for asymptomatic patients due to its low utility in managing such patients in regions with low prevalence of upper gastrointestinal cancers [2]. Only 2% of asymptomatic patients had any abnormality detected at p-EGD, none of which affected their treatment plan, and hence a focus on symptomatic patients only can safely reduce p-EGD rate by 80% [24].

Others reported that most of the pathology identified at p-EGD among patients scheduled for gastric banding did not significantly influence their management; however, two early cancers were detected [25]. In addition, although obesity is a risk factor for gastroesophageal reflux and esophageal adenocarcinoma, research could not confirm a high prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus among 233 patients selected for laparoscopic gastric banding [26]. Likewise, the association between obesity and reflux remains controversial [27], and it is unclear whether BS impacts the advancement of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) [28]. Despite a somewhat inaccessible foregut after bypass surgery, the low gastric cancer incidence among Caucasians [29] may not demand routine p-EGD [30].

Opinions remain divided as to whether p-EGD should be undertaken for all BS patients. One position is that the “intuitive reasons to continue p-EGD screening of BS patients include endoscopic findings that optimize medical management for the healing of their BS in a substantial proportion of patients and/or the endoscopic findings in at least a few patients that alter or delay the surgery itself” (p. 712) [22]. Conversely, others recommended that standard p-EGD is not indicated, as many BS patients are screened in order to discover clinically significant abnormalities [11]. For example, in Turkey, none of the 755 LSG patients had macro/microscopic malignant pathological finding in the preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy [31]. In Brazil, researchers did not perform routine p-EGD on 649 LSG patients and only did when patients complained of abdominal pain or dysphagia; however, even with these symptomatic complaints, most patients had no abnormal findings [32]. Across 93.2% of BS patients, p-EGD findings were negative or had no effect on the preoperative management or choice of surgery; thus, it might not be wise to expose morbidly obese patients to a routine invasive uncomfortable procedure that carries potential (although minimal) risk [21]. Hence, authors have raised the question: “We do not screen the general population for those minor esophagogastroduodenoscopy findings; so why should we do it on people planned for bariatric surgery?” (p. 414) [21]. Likewise, a comment on “Is esophagogastroduodenoscopy before Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy mandatory?” concluded that p-EGD had no value in prediction or prevention of postoperative complications [33].

Such inconsistency highlights a gap as to whether routine p-EGD is sufficiently justified for all BS patients, and inspired the current systematic review and meta-analysis of the significance of routine p-EGD screening in BS. To the best of our knowledge, there exists no systematic review of the English literature on the topic, and no meta-analysis has been undertaken to answer this important question. Globally, many upper gastrointestinal endoscopies are performed for inappropriate indications, and the overuse of healthcare negatively affects healthcare quality and places pressure on endoscopy services [34]. Therefore, the current systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the justifications as to whether p-EGD should be routinely undertaken for all BS patients.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement. The study was registered at the International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO CRD42020157596).

Literature Searches

A systematic review was carried out using PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Scopus, clinicaltrials.gov, and Google scholar electronic databases. We used the keywords “bariatric surgery” “Esophagogastroduodenoscopy,” “preoperative” [in Title/Abstract]. The medical subject headings (MeSH) terms used were bariatric surgery (All Fields) AND “Esophagogastroduodenoscopy” (MeSH Terms); bariatric surgery (All Fields) AND “preoperative AND Esophagogastroduodenoscopy” (MeSH Terms); bariatric surgery (All Fields) AND “preoperative OR Esophagogastroduodenoscopy” (MeSH Terms). Additional searches were conducted using the reference lists of studies and review articles for a selection of relevant articles. The references of all included articles or relevant reviews were cross-checked.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were (1) original studies, (2) English language, (3) published from 01 January 2000 through 30th April 2019, (4) assessed “Esophagogastroduodenoscopy” and “bariatric surgery,” and, (5) patients of any age, gender, and ethnicity. Articles other than original studies such as commentaries, letters to the editor, reviews, case reports, and studies that did not include outcomes or comparisons were also excluded. The consensus on the inclusion/exclusion criteria was premised on the fact that whether a given study provided information on the association between p-EGD and post-operative outcomes among bariatric surgery patients. Therefore, even studies with smaller sample sizes were also included in the initial evaluation. Three authors independently abstracted the data.

Objectives

To assess the significance of routine p-EGD screening in BS, the specific objectives were to:

Conduct a systematic review of the literature in order to identify all relevant articles on the topic;

Employ Sharaf et al.’s classification [6] of predetermined criteria to categorize the p-EGD findings of each article into the four groups (detailed below);

Compute the yield of p-EGD findings of each article in terms of the four groups of Sharaf et al.’s classification [6]; and,

Use the findings emerging from the meta-analysis to make informed judgments of the justification as to whether p-EGD should be routinely undertaken for all BS patients or otherwise.

Categorization of P-EGD Findings

In order to gauge the value of routine p-EGD screening in BS, we employed Sharaf et al.’s classification [6] of predetermined criteria to categorize p-EGD findings into four groups:

Group 0: no abnormal p-EGD findings, i.e., normal.

Group 1: abnormal p-EGD findings that do not necessitate changing the surgical approach or postponing surgery (e.g., mild esophagitis, gastritis and/or duodenitis, esophageal web).

Group 2: abnormal p-EGD findings that change the surgical approach or postpone surgery (e.g., mucosal/submucosal mass lesions, ulcers, severe erosive esophagitis, gastritis, and/or duodenitis, Barrett’s esophagus, Bezoar, hiatal hernia, peptic stricture, Zenker’s or esophageal diverticula, arteriovenous malformations).

Group 3: p-EGD findings that signify absolute contraindications to surgery (e.g., upper gastrointestinal cancers and varices).

Data Extraction

The titles of the research articles obtained from the initial database searches were screened and relevant papers were selected. Then the abstracts and full texts were reviewed according to the inclusion criteria for final selection. Three authors independently reviewed the studies based on the exclusion and inclusion criteria. Initially, titles of the studies identified from the search were assessed for inclusion. Titles approved by the authors were moved to abstract screening. If three authors rejected a study at this stage, it was excluded from the review. In the third stage, full text articles were screened for eligibility. Only those studies approved by the three authors were included in the review. Agreement between the authors on the quality of the articles ranged between 90 and 100%. All disagreements were resolved by consensus among the authors. Data extracted from the selected articles included authors, the origin of studies, source population, study settings and duration, inclusion/exclusion criteria, data sources and measurement, sample size, and the yield of p-EGD findings in terms of the four groups of Sharaf et al.’s classification [6].

Methodological Quality

The methodological quality of the selected studies was assessed based on five STROBE criteria from the checklist, namely, study design, setting, participants, data sources/measurement, and study size. The STROBE checklist and the five criteria selected from the checklist were most relevant in the assessment of the methodological quality of observational studies in epidemiology (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary and quality assessment of eligible studies for the meta-analysis in the current review

| Author a | Procedure | Study design | Sample | Data collection | D b | Country | Patients N | Female (%) | Age c | Group 0 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | H Pylori | H Hd | S patients | STROBE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 Frigg [18] | LAGB | P | C | 1996–2000 | 4 | Switzerland | 104 | 84 | 39 | 46 | 47 | 14 | 0 | 23 | 13 | — | Complete |

| 2002 Schirmer [40] | RYGB | R | C | 1986–2001 | 15 | USA | 536 | — | — | 510 | 17 | 9 | 0 | 62/206 | 3 | — | Complete |

| 2004 Sharaf [6] | Multiple procedures | P | C | 2000–2002 | 2 | USA | 195 | — | — | 20 | 19 | 93 | 0 | — | 78 | — | Complete |

| 2006 Azagury [41] | LRYGB | R | C | 1997–2004 | 7 | Switzerland | 319 | 82.1 | 40.4 | 172 | 33 | 65 | 0 | 124/318 | 54 | — | Complete |

| 2006 Korenkov [24] | LAGB | P | C | 1997–2004 | 7 | Germany | 145 | 72.4 | 39.8 | 130 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 17/145 | 8 | — | Complete |

| 2006 Zeni [42] | LRYGB | R | C | 2004–2005 | 1 | USA | 159 | 81.8 | 41.1 | 53 | 80 | 68 | 1 | 1/53 | 56 | 9 | Complete |

| 2007 Teivelis [43] | LRYGB | R | C | — | — | Brazil | 42 | 87.5 | 42 | — | 26 | 2 | 0 | 25/42 | — | — | Complete |

| 2008 Al Akwaa [44] | Multiple procedures | R | C | 2004–2007 | 3 | Saudi Arabia | 65 | 65 | 42 | 15 | 51 | 9 | 1 | — | 8 | — | Complete |

| 2008 de Moura Almeida [45] | Multiple procedures | P | C | 2004–2005 | 1 | Brazil | 162 | 69.8 | 36.7 | 37 | 157 | 18 | 0 | 36/96 | 14 | — | Complete |

| 2008 Loewen [22] | Multiple procedures | R | C | 2004–2006 | 2 | USA | 447 | 87 | 40.6 | 316 | 96 | 62 | 0 | 9/61 | 40 | — | Complete |

| 2008 Mong [9] | LRYGB | R | C | 2000–2005 | 5 | USA | 272 | 87.1 | 43 | — | 37 | 10 | 1 | — | — | 40 | Complete |

| 2009 Munoz [14] | LRYGB | P | C | 1999–2006 | 7 | Chile | 626 | 72.2 | 38.5 | 338 | 281 | 108 | 1 | 280/533 | 67 | — | Complete |

| 2010 Bueter [35] | LAGB | P | C | 1997–2006 | 9 | UK | 68 | 85.3 | 34 | — | 33 | 22 | 0 | — | 22 | — | Complete |

| 2010 Küper [8] | Multiple procedures | P | C | Jan-Dec 2008 | 11 m | Germany | 69 | 62.3 | 43.4 | — | 33 | 45 | 3 | 6/69 | 19 | 11/55 | Complete |

| 2012 Dietz [36] | Multiple procedures | P | C | — | — | Brazil | 126 | 82.5 | 42.1 | 53 | 75 | 4 | 0 | 67/126 | — | — | Complete |

| 2012 Humphreys [25] | LAGB | P | C | 2003–2010 | 7 | UK | 371 | 72.2 | 45 | 164 | 148 | 129 | 2 | 14/207 | 90 | — | Complete |

| 2013 D’hondt [37] | LRYGB | R | C | 2003–2010 | 7 | Belgium | 652 | 70.9 | 39.5 | 208 | 437 | 208 | 2 | 115/652 | 159 | — | Complete |

| 2013 Peromaa-Haavisto [23] | LRYGB | P | C | 2006–2010 | 4 | Finland | 412 | 50.5 | — | 191 | 95 | 117 | 1 | 41/412 | 87 | — | Complete |

| 2014 Gómez [38] | Multiple procedures | R | C | 2006–2013 | 7 | USA | 232 | 82.3 | 51 | — | 98 | 78 | 4 | 8/232 | 55 | — | Complete |

| 2014 Petereit [39] | LRYGB | P | C | 2010–2013 | 3 | Lithuania | 180 | 71.1 | 42.7 | 74 | 110 | 37 | 0 | 108/180 | 37 | — | Complete |

| 2014 Schigt [11] | Multiple procedures | P | C | 2007–2012 | 5 | Netherlands | 523 | 76.7 | 44.3 | 257 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 84/523 | — | — | Complete |

| 2014 Tolone [28] | Multiple procedures | P | C | — | — | Italy | 124 | 41.9 | 36 | — | 18 | 23 | 0 | — | 23 | — | Complete |

| 2016 Abd Ellatif [21] | Multiple procedures | P | C | 2001–2015 | 4 | Kuwait, KSA, Egypt | 3219 | 79 | 37 | 2414 | 410 | 409 | 0 | 407/3219 | 383 | — | Complete |

| 2017 Lee [30] | Multiple procedures | P | C | 2002–2014 | 12 | China | 268 | — | — | 138 | 109 | 74 | 14 | 58/243 | 48 | — | Complete |

| 2017 Salama [2] | LSG | R | C | 2011–2014 | 3 | Qatar | 1369 | 69.7 | 35.65 | 675 | 550 | 144 | 0 | 597/1369 | 96 | — | Complete |

aDue to space limitations, only the first author is cited; D Duration of study; byears; cmean age in years; HH Hiatus hernia; dnumber of patients; S Symptomatic; P prospective; R retrospective; C Convenience; LAGB Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass; LRYGB laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; LSG Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy; m months; KSA Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; — not reported

Data Analysis and Synthesis

Prevalences were calculated for categorical variables. The decision to employ either a fixed-effect or random effect model depended on the results of statistical tests for heterogeneity. Data heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochrane Q homogeneity test (significance set at p < 0.10). If the studies were statistically homogeneous, a fixed-effect model was selected. A random effect model was used when studies were statistically heterogeneous. The Higgin’s I2 test is the ratio of true heterogeneity to the total variation in observed effects. A rough guide to interpretation of I2 test is 0–25%: might not be important; 25–50%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50–75%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; and > 75%: considerable heterogeneity. Publication bias was visually estimated by assessing funnel plots. Pooled estimates were calculated using the R 3.5.1 software.

Results

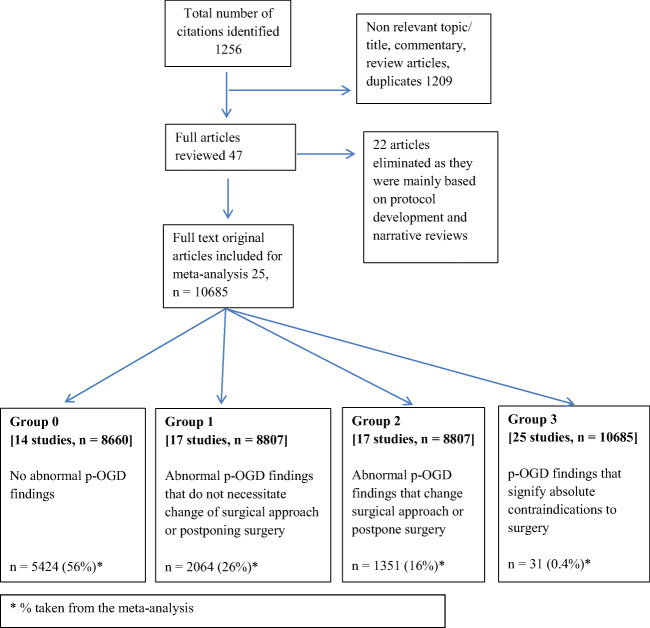

The search generated a total of 1256 articles; 1209 articles were either non-relevant to the topic, duplicates, or review articles which were excluded. The relevant titles and/or abstracts and full text of the remaining 47 articles underwent detailed evaluation, after which 22 articles were further eliminated as these were mainly based on protocol development and narrative reviews. Finally, 25 original studies met all the review criteria and were considered for the final meta-analysis (Fig. 1 and Table 1) [2, 6, 8, 9, 11, 14, 18, 21–25, 28, 30, 35–45].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection process for systematic review

Median study duration was 4 years with an inter quartile range of 2–7 years. Overall average age was 40.7 years, and overall average percentage of males (25%) was lower than females (75%). All studies were non-randomized controlled trials, comprising 15 prospective and 10 retrospective studies. These studies had low or unclear risk of bias, unlikely to seriously alter the results. In addition, these studies had no serious risk of bias that can downgrade the quality. There was no inconsistency: the study populations were BS patients, and outcome assessment was consistent, namely the yield of p-EGD findings in terms of the four groups of Sharaf et al.’s classification [6].

Outcome Measures

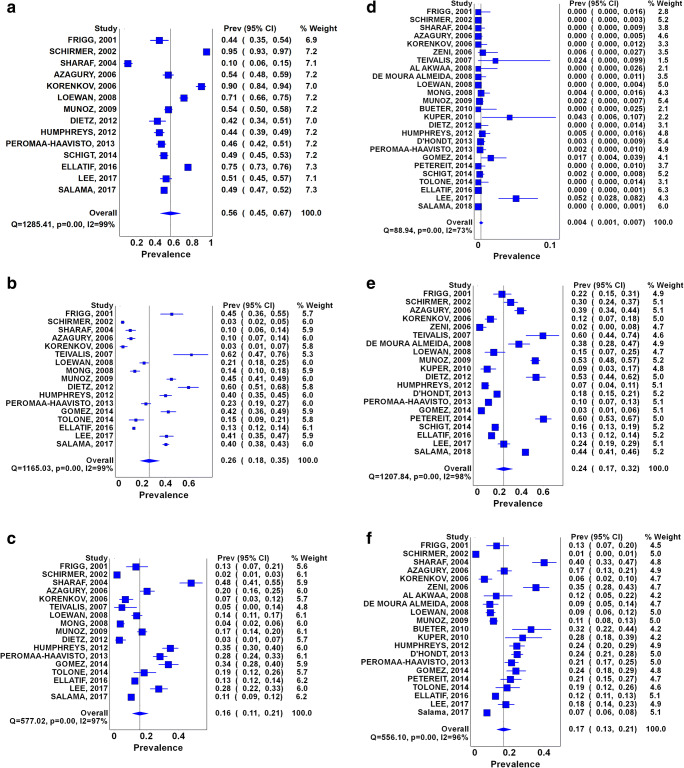

The total number of patients pooled was 10,685. Figure 2 depicts the meta-analysis of the 4 groups (groups 0–3) of patients based on their p-EGD findings. The largest group was Group 0 (no abnormal p-EGD findings, 56%, 95% CI: 45–67%) followed by Group 1 (abnormal p-EGD findings that do not necessitate changing the surgical approach or postponing surgery, 26%, 95% CI: 18–35%). These were followed by Group 2 (abnormal p-EGD findings that change the surgical approach or postpone surgery, 16%, 95% CI: 11–21%) and Group 3 (p-EGD findings that signify absolute contraindications to surgery, 0.4%, 95% CI: 0–1%). H. pylori infection was positive among about one-fourth of patients, and hiatal hernia was present in a mean of 17% of patients.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of a no abnormal p-EGD findings (Group 0); b abnormal p-EGD findings that do not necessitate changing the surgical approach (Group 1); c abnormal p-EGD findings that change the surgical approach or postpone surgery (Group 2); d p-EGD findings that signify absolute contraindications to surgery (Group 3); e H. pylori infection; f Hiatal hernia

Heterogeneity Among Included Studies

The results for the test of heterogeneity for the meta-analysis among bariatric surgery patients are displayed in the bottom line to the left of each Forest plot. For Group 0 (no abnormal p-EGD findings), Q [χ2] = 1285.41, P = 0.001, I2 = 99%, tau2 = 0.0159 (Fig. 2a); for Group 1 (abnormal p-EGD findings that do not necessitate changing the surgical approach or postponing surgery), Q [χ2] = 165.03, P = 0.001, I2 = 99%, tau2 = 0.140 (Fig. 2b); for Group 2 (abnormal p-EGD findings that change the surgical approach or postpone surgery), Q [χ2] = 557.02, P = 0.001, I2 = 97% tau2 = 0.077 (Fig. 2c); for Group 3 (p-EGD findings that signify absolute contraindications to surgery) Q [χ2] = 557.02, P = 0.001, I2 = 72%, tau2 = 0.007 (Fig. 2d); for H pylori infection Q [χ2] = 1207.84, P = 0.001, I2 = 98%, tau2 = 0.007 (Fig. 2e); and, for hiatal hernia Q [χ2] = 556.10, P = 0.001, I2 = 96%, tau2 = 0.196 (Fig. 2f). However, as I2 was > 25%, a random effect model was considered. Tau2 reflect the amount of true heterogeneity among the studies.

Publication Bias and Funnel Plots

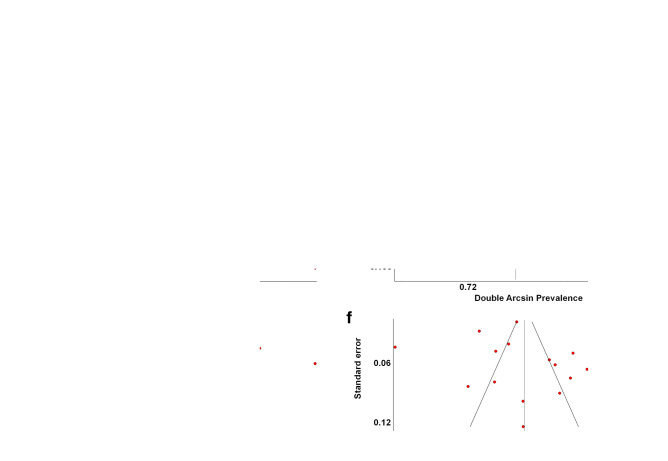

For all of the above analyses, sensitivity analysis yielded consistent results. Based on a visual inspection of the funnel plots, there was evidence of publication bias for the included studies (Fig. 3). The funnel plots exhibited presence of studies with large standard error and they were not symmetrical.

Fig. 3.

Funnel plots of a no abnormal p-EGD findings (Group 0); b abnormal p-EGD findings that do not necessitate changing the surgical approach (Group 1); c abnormal p-EGD findings that change the surgical approach or postpone surgery (Group 2); d p-EGD findings that signify absolute contraindications to surgery (Group 3); e H. pylori infection; f Hiatal hernia

Limitation

The studies included in this meta-analysis did not report the frequency of multiple abdominal conditions. Rather, the studies reported the frequency of each abdominal condition separately. Hence, there might be a probability of multiple abdominal conditions for a single patient which would influence the overall estimation in Groups 1 and 2.

Discussion

The current systematic review and meta-analysis is the first to assess the yield of p-EGD findings in terms of four groups [6], in order to gauge justifications as to whether p-EGD should be routine for all BS patients. Routine p-EGD can diagnose rare gastric pathologies [19]. The current review showed that 82% of patients had either no abnormal p-EGD findings (Group 0) or abnormal p-EGD findings that do not necessitate changing the surgical approach or postponing surgery (Group 1). Another 16% of patients required changing the surgical approach or postponing surgery based on the p-EGD findings (Group 2). Only 0.4% of patients had p-EGD findings that signified absolute contraindication to surgery (Group 3).

Generally, EGD carries risks to patients, as well as legal risks [46]. Hence, in addition to the p-EGD ‘yield’ in discovering/excluding pathologies, the appropriate gauging of whether routine p-EGD is justified for all BS patients needs to consider several parameters. These include the following: adverse effects of routine p-EGD; missing or over-diagnoses of lesions (false negatives, false positives); skill level of the esophagogastroduodenoscopy personnel; availability and cost of alternative (non-invasive) diagnostic methods to discover upper gastrointestinal pathology; and the costs of routine p-EGD. A related point is the changes that could occur to any missed pathology across time: i.e., initially before and then subsequent to BS (histological patterns of cellular alterations after gastric surgeries).

Adverse effects of esophagogastroduodenoscopy include infections, bleedings or perforations [47, 48], acute pancreatitis (direct trauma/gas insufflation) [49]; cardiopulmonary events [48]; methemoglobinemia (genetic predispositions/use of topical anesthetics) [50]; hypoxic respiratory failure/critical events requiring bronchoscopic intratracheal oxygen insufflation [8, 51]; orbital hematoma [52]; and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy with complete heart block [53]. Other effects include pre-endoscopy anxiety (unsedated esophagogastroduodenoscopy) [54], effects related to comorbidities of e.g., morbidly obese diabetic patients where the overnight fasting challenges the metabolic status, and sleep apnea (needs surveillance during sedation) [8]. Despite these, some authors suggest that the infrequent adverse events should not limit routine p-EGD [55].

As for missing important lesions (false negatives), the quality of the esophagogastroduodenoscopy varies [56]. In Spain, 17 out of 187 gastric cancer patients had prior esophagogastroduodenoscopy (9.1%), and 12 of those 17 missed gastric cancer had prior esophagogastroduodenoscopy with abnormal findings [57]. P-EGD is also frequently inaccurate at diagnosing hiatal hernia (particularly large hernias), where 23 patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy had paraesophageal hernia intraoperatively; many of these patients were asymptomatic, and p-EGD revealed large hiatal hernia in only 4 patients [58–60]. Conversely, hiatal hernia repair was performed in 56 (5%) of patients positive for intraoperative findings despite a negative p-EGD for hiatal hernia [55]. A related point here pertains to the probability of changes of a given missed lesion, i.e., the changes of pathology across time and the histological cellular alterations after gastric surgeries [61]. Pre-surgery biopsies of 798 LSG patients showed non-significant findings in 86.2%; among them, 99.7% maintained a pattern without relevance for its follow-up; and some patients who had intestinal metaplasia reversed its histopathology (maybe following H. pylori treatment) [62]. Others found that the pre-operative inflammatory alterations were reduced post-operatively, where the chronic gastritis with inflammatory activity associated with H. pylori was reduced by 16.7%, and foveolar hyperplasia was reduced by 25% [61]. Further research can evaluate whether such improvements are due to treatment of H. pylori [61].

In terms of false positives, EGD over-diagnosed small hiatal hernias, most did not require repair, and 60% of EGD positive hiatal hernias were found to be negative intraoperatively [55]. Both the presence of symptoms and EGD findings may not always correlate with intraoperative findings [55]. In the current meta-analysis, p-EGD findings suggested hiatal hernia in a mean of 17% of patients (95% CI: 13–21%). However, the data provided by the studies does not enable one to speculate how many hiatal hernias/other lesions were missed or over-diagnosed during these EGDs.

In connection with the skill level, p-EGD has some subjectivity; hence, the endoscopist’s expertise could lead to over/under diagnoses [55, 63]. The endoscopist is vital in missed gastric cancer [57], and training/learning interventions could enhance the quality of endoscopy [63]. About 51.8% of the incomplete endoscopy reports did not have justification for its incompleteness [64]. Patients with no symptoms or no esophagogastroduodenoscopy evidence of hiatal hernias had hernia repairs (4%–6%), suggesting that small hiatal hernias are operator-dependent diagnoses [55]. The studies included in the current meta-analysis did not examine such skills, and we are unable to conclude how this might have affected the p-EGD yield we computed.

In terms of alternative diagnostic methods for gastric cancer pathologies, there are novel noninvasive screening techniques for e.g., Barrett’s esophagus [65] and H. pylori [66–68]. However, some authors might view that some novel techniques might be inferior to established gold standards, not all institutions might have advanced alternative diagnostic technologies, and esophagogastroduodenoscopy allows both the direct visualization and tissue biopsy [55].

Endoscopy is costly [1]. In the USA, the average hospital cost of an esophagogastroduodenoscopy with and without biopsy was $3732 and $3038 [69]. Endoscopy necessitates time, money, and personnel resources including experienced investigators, anesthesiological support, and special surveillance [8].

The current meta-analysis found that Group 2 patients (abnormal p-EGD findings that change the surgical approach or postpone surgery) amounted to 16%. However, it is not clear what proportion of these patients were postponed solely for H. pylori medical treatment as opposed to a “true” more substantial esophagogastroduodenoscopy-informed change in the surgical approach. This is important, as some might argue that if H. pylori is diagnosed by a non-invasive method (no need for esophagogastroduodenoscopy), and if the surgery waiting list time at a given institution is > 2–4 weeks (sufficient time for H. pylori treatment), then no postponement might have been required. One inquiry [2] examined the postponement, cancelation, or change of surgical approach based on the p-EGD findings across several sleeve gastrectomy studies and found that a considerable number of Group 2 patients were postponed solely for the treatment of H. pylori. This research [2] reported that across three studies, 21.5% [6], 12% [10], and 27% [30] of Group 2 patients had their BS postponed for H. pylori treatment, or waiting for H. pylori test result to assess severity of inflammation after medical treatment. Such findings suggest, that for the present meta-analysis, it might be reasonable to speculate that the proportion of Group 2 patients postponed due to a “true” change in surgical approach could be much less that the current 16%, further questioning the utility of routine p-EGD.

This review searched most of the citation databases and reference lists of the included studies. We also accessed paid articles. Nevertheless, a limitation of the current meta-analysis is that it included only published studies and only the English literature. We could not find “gray” literature, and hence, potential publication bias cannot be excluded. There were no studies from some regions of the world. However, 25 studies were included in this meta-analysis and we had a sizeable sample of 10,685 patients.

Conclusions

The findings of this meta-analysis compel a revisit of current practice, and a re-evaluation of why p-EGD should be routine for all bariatric surgery patients. In 2016, about 634,897 bariatric operations were performed worldwide [70]. It might not be totally judicious to expose very large numbers of morbidly obese patients to a routine invasive uncomfortable procedure that has potential (although minimal) risk and insufficient evidence of effectiveness. Limitations include the lack of studies from some world regions and a small number of studies.

Authorship

WEA was involved in the conceptualization and design of this study. AE, SB, and WEA searched databases, screened articles extracted data. SB performed the acquisition and analysis of data. AE, SB, and WEA interpreted the data. WEA AE, and SB drafted the manuscript. HAT, MA and AA critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. WEA is the guarantor of this study.

Funding Information

Open Access funding for the publication of this article provided by Qatar National Library.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

For this type of study, ethical approval and informed consent do not apply as it is a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Walid El Ansari, Email: welansari9@gmail.com.

Ayman El-Menyar, Email: aymanco65@yahoo.com.

Brijesh Sathian, Email: BSathian@hamad.qa.

Hassan Al-Thani, Email: althanih@hotmail.com.

Mohammed Al-Kuwari, Email: malkuwari2@hamad.qa.

Abdulla Al-Ansari, Email: AALANSARI1@hamad.qa.

References

- 1.Lalor PF. Comment on: is esophagogastroduodenoscopy before Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy mandatory? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):417–418. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salama A, Saafan T, El Ansari W, Karam M, Bashah M. Is routine preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy screening necessary prior to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy? Review of 1555 Cases and Comparison with Current Literature. Obes Surg. 2018;28(1):52–60. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2813-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauerland S, Angrisani L, Belachew M, Chevallier JM, Favretti F, Finer N, Fingerhut A, Garcia Caballero M, Guisado Macias JA, Mittermair R, Morino M, Msika S, Rubino F, Tacchino R, Weiner R, Neugebauer EAM. Obesity surgery: evidence-based guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) Surg Endosc. 2005;19:200–221. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-9194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SAGES Guidelines Committee SAGES guideline for clinical application of laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5(3):387–405. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SICOB Linee Guida di Chirurgia dell’ Obesita. Società Italiana di Chirurgia dell’Obesità e della Malattie Metaboliche. 2016 edition Available from: https://www.sicob.org/00_materiali/linee_guida_2016.pdf (accessed 17 July 2019)

- 6.Sharaf RN, Weinshel EH, Bini EJ, Rosenberg J, Sherman A, Ren CJ. Endoscopy plays an important preoperative role in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1367–1372. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verset D, Houben JJ, Gay F, Elcheroth J, Bourgeois V, van Gossum A. The place of upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy before and after vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2333–2337. doi: 10.1023/a:1018835205458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Küper MA, Kratt T, Kramer KM, Zdichavsky M, Schneider JH, Glatzle J, Stüker D, Königsrainer A, Brücher BL. Effort, safety, and findings of routine preoperative endoscopic evaluation of morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(8):1996–2001. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0893-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mong C, Van Dam J, Morton J, et al. Preoperative endoscopic screening for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has a low yield for anatomic findings. Obes Surg. 2008;18(9):1067–1073. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Praveenraj P, Gomes RM, Kumar S, Senthilnathan P, Parathasarathi R, Rajapandian S, Palanivelu C. Diagnostic yield and clinical implications of preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25(6):465–469. doi: 10.1089/lap.2015.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schigt A, Coblijn U, Lagarde S, Kuiken S, Scholten P, van Wagensveld B. Is esophagogastroduodenoscopy before Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy mandatory? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lord RV, Edwards PD, Coleman MJ. Gastric cancer in the bypassed segment after operation for morbid obesity. Aust N Z J Surg. 1997;67:580–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1997.tb02047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khitin L, Roses RE, Birkett DH. Cancer in the gastric remnant after gastric bypass. Curr Surg. 2003;60:521–523. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7944(03)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munoz R, Ibanez L, Salinas J, et al. Importance of routine preoperative upper GI endoscopy: why all patients should be evaluated? Obes Surg. 2009;19:427–431. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seva-Pereira G, Trombeta VL. Early gastric cancer found at preoperative assessment for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1109–1111. doi: 10.1381/096089206778026343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boru C, Silecchia G, Pecchia A, Iacobellis G, Greco F, Rizzello M, Basso N. Prevalence of cancer in Italian obese patients referred for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1171–1176. doi: 10.1381/0960892055002284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cowan GSM, Hiler ML. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in bariatric surgery. In: Deitel M, editor. Update: Surgery for the Morbidly Obese Patient. Toronto: FD-Communications Inc; 2000. pp. 387–416. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frigg A, Peterli R, Zynamon A, Lang C, Tondelli P. Radiologic and endoscopic evaluation for laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: preoperative and follow-up. Obes Surg. 2001;11:594–599. doi: 10.1381/09608920160557075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dogan U, Suren D, Oruc MT, Gokay AA, Mayir B, Cakir T, Aslaner A, Oner OZ, Bulbuller N. Spectrum of gastric histopathologies in morbidly obese Turkish patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21(23):5430–5436. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201712_13931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson MA, Gan SI, Fanelli RD, Baron TH, Baneerje S, Cash BD, Dominitz JA, Harrison ME, Ikenberry SO, Jagannath SB, Lichtenstein DR, Shen B, Lee KK, Van Guilder T, Stewart LE. Role of endoscopy in the bariatric surgery patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abd Ellatif ME, Alfalah H, Asker WA, El Nakeeb AE, Magdy A, Thabet W, Ghaith MA, Abdallah E, Shahin R, Shoma A, Dawoud IE, Abbas A, Salama AF, Ali GM. Place of upper endoscopy before and after bariatric surgery: a multicenter experience with 3219 patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8(10):409–417. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i10.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loewen M, Giovanni J, Barba C. Screening endoscopy before bariatric surgery: a series of 448 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(6):709–712. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peromaa-Haavisto P, Victorzon M. Is routine preoperative upper GI endoscopy needed prior to gastric bypass? Obes Surg. 2013;23:736–739. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0956-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korenkov M, Sauerland S, Shah S, Junginger T. Is routine preoperative upper endoscopy in gastric banding patients really necessary? Obes Surg. 2006;16(1):45–47. doi: 10.1381/096089206775222104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphreys LM, Meredith H, Morgan J, Norton S. Detection of asymptomatic adenocarcinoma at endoscopy prior to gastric banding justifies routine endoscopy. Obes Surg. 2012;22(4):594–596. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0506-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masci E, Viaggi P, Mangiavillano B, Di Pietro S, Micheletto G, Di Prisco F, Paganelli M, Pontiroli AE, Laneri M, Testoni S, Testoni PA. No increase in prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus in a surgical series of obese patients referred for laparoscopic gastric banding. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(8):613–615. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corley DA, Kubo A. Body mass index and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;108:2619e2628. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tolone S, Limongelli P, del Genio G, Brusciano L, Rossetti G, Amoroso V, Schettino P, Avellino M, Gili S, Docimo L. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity: do we need to perform reflux testing in all candidates to bariatric surgery? Int J Surg. 2014;12(Suppl 1):S173–S177. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD; [updated 2015 April; cited 2019 Dec 12] Available from http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/.

- 30.Lee J, Wong SK, Liu SY, Ng EK. Is preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery mandatory? An Asian Perspective. Obes Surg. 2017;27(1):44–50. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yardimci E, Bozkurt S, Baskoy L, Bektasoglu HK, Gecer MO, Yigman S, Akbulut H, Coskun H. Rare entities of histopathological findings in 755 sleeve gastrectomy cases: a synopsis of preoperative endoscopy findings and histological evaluation of the specimen. Obes Surg. 2018;28(5):1289–1295. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-3014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ge L, Moon RC, Nguyen H, de Quadros LG, Teixeira AF, Jawad MA. Pathologic findings of the removed stomach during sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:4003–4007. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-06689-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coblijn UK, Kuiken SD, van Wagensveld BA. Comment on: is esophagogastroduodenoscopy before Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy mandatory? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(5):1192–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Jong JJ, Lantinga MA, Drenth JP. Prevention of overuse: a view on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(2):178–189. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bueter M, Thalheimer A, Le Roux CW, Wierlemann A, Seyfried F, Fein M. Upper gastrointestinal investigations before gastric banding. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(5):1025–1030. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0720-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dietz J, Ulbrich-Kulcynski JM, Souto KEP, Meinhardt NG. Prevalence of upper digestive endoscopy and gastric histopathology findings in morbidly obese patients. Arq Gastroenterol. 2012;49(1):52–55. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032012000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Hondt M, Steverlynck M, Pottel H, Elewaut A, George C, Vansteenkiste F, et al. Value of preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy in morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Acta Chir Belg. 2013;113(4):249–253. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2013.11680922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gómez V, Bhalla R, Heckman MG, Florit PTK, Diehl NN, Rawal B, Lynch SA, Loeb DS. Routine screening endoscopy before bariatric surgery: is it necessary? Bariatr Surg Pract Patient Care. 2014;9(4):143–149. doi: 10.1089/bari.2014.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petereit R, Jonaitis L, Kupcˇinskas L, Maleckas A. Gastrointestinal symptoms and eating behavior among morbidly obese patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Medicina (Kaunas) 2014;50(2):118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schirmer B, Erenoglu C, Miller A. Flexible endoscopy in the management of patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2002;12(5):634–638. doi: 10.1381/096089202321019594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azagury D, Dumonceau JM, Morel P, Chassot G, Huber O. Preoperative work-up in asymptomatic patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: is endoscopy mandatory? Obes Surg. 2006;16(10):1304–1311. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeni TM, Frantzides CT, Mahr C, Denham EW, Meiselman M, Goldberg MJ, Spiess S, Brand R. Value of preoperative upper endoscopy in patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2006;16(2):142–146. doi: 10.1381/096089206775565177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teivelis MP, Faintuch J, Ishida R, Sakai P, Bresser A, Gama-Rodrigues J. Endoscopic and ultrasonographic evaluation before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Arq Gastroenterol. 2007;44(1):8–13. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032007000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al Akwaa AM, Alsalman A. Benefit of preoperative flexible endoscopy for patients undergoing weight-reduction surgery in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(1):12–14. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.37795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Moura AA, Cotrim HP, Santos AS, Bitencourt AGV, Barbosa DBV, Lobo AP, et al. Preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery: is it necessary? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(2):144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adler DG. Consent, common adverse events, and post-adverse event actions in endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2015;25(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jałocha L, Wojtuń S, Gil J. Incidence and prevention methods of complications of gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2007;22(131):495–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Standards of Practice Committee. Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, et al. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(4):1063–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nwafo NA. Acute pancreatitis following oesophagogastroduodenoscopy. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr-2017-222272. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khan K, White-Gittens I, Saeed S, Ahmed L. Benzocaine-induced methemoglobinemia in a postoperative bariatric patient following esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Case Rep Crit Care. 2019;2019:1571423. doi: 10.1155/2019/1571423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiens EJ, Mylnikov A. Hypoxic respiratory failure complicating esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(5):706. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lotlikar M, Pandey V, Chauhan S, Ingle M, Shukla A. Orbital hematoma: a new complication of esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(1):181–182. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang AN, Sacchi T, Altschul R, Guss D, Mohanty SR, Notar-Francesco V. A case of esophagogastroduodenoscopy induced Takotsubo cardiomyopathy with complete heart block. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2019;12:296–300. doi: 10.1007/s12328-019-00967-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang M, Lu LL, Zhao M, Liu J, Li QL, Li Q, Xu P, Fu L, Luo LM, He JH, Meng WB, Lei PG, Yuan JQ. Associations of anxiety with discomfort and tolerance in Chinese patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mohammed R, Fei P, Phu J, Asai M, Antanavicius G. Efficiency of preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy in identifying operable hiatal hernia for bariatric surgery patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(2):287–290. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang LW, Lin H, Xin L, Qian W, Wang TJ, Zhang JZ, Meng QQ, Tian B, Ma XD, Li ZS. Establishing a model to measure and predict the quality of gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(8):1024–1030. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i8.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Delgado Guillena PG, Morales Alvarado VJ, Jimeno Ramiro M, et al. Gastric cancer missed at esophagogastroduodenoscopy in a well-defined Spanish population. Dig Liver Dis. 2019; 51(8): 1123–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Pham DV, Protyniak B, Binenbaum SJ, Squillaro A, Borao FJ. Simultaneous laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair and sleeve gastrectomy in the morbidly obese. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(2):257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Daes J, Jimenez ME, Said N, Daza JC, Dennis R. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux can be reduced by changes in surgical technique. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1874–1879. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0746-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soricelli E, Casella G, Rizzello M, Cali B, Alessandri G, Basso N. Initial experience with laparoscopic crural closure in the management of hiatal hernia in obese patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1149–1153. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Onzi TR, d'Acampora AJ, de Araújo FM, Baratieri R, Kremer G, Lyra HF, Jr, Leitão JT. Gastric histopathology in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: pre- and post-operative comparison. Obes Surg. 2014;24(3):371–376. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Canil AM, Iossa A, Termine P, Caporilli D, Petrozza V, Silecchia G. Histopathology findings in patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2018;28(6):1760–1765. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-3092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu L, Zhang J, Zhou W, et al. Randomised controlled trial of WISENSE, a real-time quality improving system for monitoring blind spots during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Gut. 2019; 68(12): 2161–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Lisboa-Gonçalves P, Libânio D, Marques-Antunes J, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Pimentel-Nunes P. Quality of reporting in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: effect of a simple audit intervention. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2018;26(1):24–32. doi: 10.1159/000487145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanghi V, Thota PN. Barrett’s esophagus: novel strategies for screening and surveillance. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10:2040622319837851. doi: 10.1177/2040622319837851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guarner J, Kalach N, Elitsur Y, Koletzko S. Helicobacter pylori diagnostic tests in children: review of the literature from 1999 to 2009. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:15–25. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Erzin Y, Altun S, Dobrucali A, Aslan M, Erdamar S, Dirican A, Kocazeybek B. Evaluation of two enzyme immunoassays for detecting Helicobacter pylori in stool specimens of dyspeptic patients after eradication therapy. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:863–866. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45914-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Erzin Y, Altun S, Dobrucali A, Aslan M, Erdamar S, Dirican A, Kocazeybek B. Comparison of two different stool antigen tests for the primary diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in turkish patients with dyspepsia. Helicobacter. 2004;9:657–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson JM, Carter TM, Schwartz RW, Gagliardi J. P24: pre-operative upper endoscopy in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is not mandatory. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:307. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Vitiello A, Higa K, Himpens J, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. IFSO worldwide survey 2016: primary, endoluminal, and revisional procedures. Obes Surg. 2018;28(12):3783–3794. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]