Abstract

There is an increasing interest in the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats CRISPR-associated protein (CRISPR-Cas) system to reveal potential virus–host dynamics. The universal and most conserved Cas protein, cas1 is an ideal marker to elucidate CRISPR-Cas ecology. We constructed eight Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and assembled cas1 directly from metagenomes by a targeted-gene assembler, Xander, to improve detection capacity and resolve the diverse CRISPR-Cas systems. The eight HMMs were first validated by recovering all 17 cas1 subtypes from the simulated metagenome generated from 91 prokaryotic genomes across 11 phyla. We challenged the targeted method with 48 metagenomes from a tallgrass prairie in Central Oklahoma recovering 3394 cas1. Among those, 88 were near full length, 5 times more than in de-novo assemblies from the Oklahoma metagenomes. To validate the host assignment by cas1, the targeted-assembled cas1 was mapped to the de-novo assembled contigs. All the phylum assignments of those mapped contigs were assigned independent of CRISPR-Cas genes on the same contigs and consistent with the host taxonomies predicted by the mapped cas1. We then investigated whether 8 years of soil warming altered cas1 prevalence within the communities. A shift in microbial abundances was observed during the year with the biggest temperature differential (mean 4.16 °C above ambient). cas1 prevalence increased and even in the phyla with decreased microbial abundances over the next 3 years, suggesting increasing virus–host interactions in response to soil warming. This targeted method provides an alternative means to effectively mine cas1 from metagenomes and uncover the host communities.

Subject terms: Microbial ecology, Climate-change ecology

Introduction

CRISPR-Cas system is mainly known as an adaptive immunity that enables the bacterial and archaeal hosts to robustly adapt to the rapidly evolving viruses by acquiring viral sequences and storing in CRISPR arrays as immunity memories [1]. Our knowledge of CRISPR-Cas system is restricted to a limited number of archaeal and bacterial genomes deposited in the public databases which cannot well-represent environmental microbiomes. A few pilot metagenome studies detected new CRISPR-Cas systems and their prevalence in the environments like acid mine drainage [2], sediments [2], marine sponge [3], and global oceans [4]. The CRISPR-Cas system in environmental microbiomes, such in soil, with high microbial diversity, and cryptic species are understudied. Some basic questions remain unanswered such as: (i) what are the subtypes and the host community of CRISPR-Cas system found in soil microbiome, and (ii) how does the CRISPR-Cas preference shift in response to environmental perturbation.

Compared with CRISPR arrays, cas genes provide more information of subtypes and host taxonomy [5]. Current methods of mining for cas genes in metagenome are based on the de-novo assembled contigs and binned genomes [6]. Assembling long contigs requires high coverage of the genomes so that the dominant microbes with low genomic heterogeneity and less repetitive regions are often more represented in de-novo assemblies [7]. Besides, the incomplete assembling of soil metagenomes generates shorter contigs, which makes cas gene annotation more problematic. In addition to the computational challenges, the viral load in soil is much lower than that in marine system, 1.5 × 108 g−1, which is approximately one soil virus for every 25 bacterial cells [8] in contrast to 0.03–11.71 × 109 g−1 viruses found in marine sediments [9]. Given the potentially low recovery of CRISPR-Cas system in soil metagenomes by current approaches, alternative methods are required.

To overcome the difficulties mentioned above, we applied a more targeted approach to assemble cas directly from the metagenomes by a targeted-gene assembler, Xander [10] using profile Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to guide de Bruijn graph traversal. This could provide an opportunity to more efficiently reveal CRISPR-Cas systems in complex microbiomes such as in soil. We targeted cas1, one of the universally conserved cas genes, to assemble as a biomarker of CRISPR-Cas system [1]. Cas1 binds to Cas2 to form a complex to initiate the adaptive immunity at the integration stage in the majority of CRISPR-Cas systems [11]. An exception is putative CRISPR-Cas subtype IV, lacking cas1, cas2, and CRISPR arrays, is carried by a plasmid and opportunistically becomes functional only when transferred into hosts with CRISPR available, which is not included in the detection here. Hence, we applied this targeted-assembly method to more robustly recover cas1 diversity and decipher CRISPR-Cas ecology.

Different soil histories or exposures to new environmental conditions drive soil microbiome changes, which could include their relationships with their viral predators. Climate change which can result in warmer soils, as well as new moisture regimes is one example of an environmental driver of microbiome change of current concern. In situ experimental soil warming studies have been conducted in various ecosystems including temperate forest soils [12, 13], temperate grassland soils [14, 15], high latitude alpine meadows [16], Antarctic peninsula [17], and Alaska tundra [18, 19], among which microbial succession and their ecological functions have been investigated but not potential interactions between prokaryotes and viruses. cas1 may reflect the dynamics of this interaction in response to soil warming. This may show whether or how soil warming affects microbial communities and also shed light on the microbial response to environmental changes.

Materials and methods

Site description and soil property measurements

The soil warming experiment was set up at the Kessler Atmospheric and Ecological Field Station in McClain County, OK (34° 59′ N, 96° 31′ W). The mean annual temperature is 16.3 °C and mean annual precipitation is 914 mm [20]. The experiment was a blocked split-plot design and initiated in July, 2009. For each selected block, soil was sampled yearly through 2016 from three randomly selected warming replicates heated by above ground infrared radiators and from three paired ambient control plots located 5 m away. The sampling scheme, soil properties measurements, and DNA extraction from 48 soil samples used (2 treatments, 3 replicates over 8 years) were reported previously [15, 21].

Constructing Cas1 HMMs and Xander packages

The three files for automatically generating a Xander package include (1) a fasta file containing seed sequences; (2) an HMM, and (3) a fasta file containing a more diverse collection of the targeted protein sequences (framebot.fa). Near full length of cas1 protein sequences were retrieved from GenBank [22] for the well-curated protein family seed sequences in Pfam [23] (Pfam 01867), TIGERFAM [24] (TIGRFAM00287, TIGRFAM03637, TIGRFAM03638, TIGRFAM03639, TIGRFAM03640, TIGRFAM03641, TIGRFAM03983, TIGRFAM04093, and TIGRFAM04329) and the recent literature [2, 25–29]. The compiled cas1 protein sequences were aligned by MAFFT [30] in Jalview (jalview.org, v. 2.10.2b2). The aligned cas1 protein sequences were dereplicated to remove the identical or substring of sequences and clustered by sequence similarity using RDPTools (ReadSeq.jar and Clustering.jar; https://github.com/rdpstaff/RDPTools). The dereplicated cas1 protein sequences grouped into seven complete-linkage clusters at 50% identity cutoff. The sequences in each cluster were used as the seed sequences to build HMMs using modified HMMER 3.0 [31] with a patch file [10]. An additional HMM was added specifically for archaeal Type II cas1 considering its novelty [2]. To prepare the third file required for a Xander package (framebot.fa), we used the respective HMM to search against the nonredundant protein sequence database (nr, NCBI) via hmmsearch [31] and collected sequences annotated as ‘Cas1’. Eight cas1 Xander packages named as M1–M8 were automatically prepared using a shell script (https://github.com/rdpstaff/Xander_assembler/blob/master/bin/).

Evaluating and improving HMM performance

We created a reference genome set including 91 bacterial and archaeal genomes across 11 phyla carrying 93 cas1 sequences of 17 subtypes from NCBI Genome database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome) (Supplementary T1) to evaluate and train the newly constructed HMMs (Fig. 1b). The subtypes included Archaeal Type II, CasX, CasY, IA-IF, IU, IIA-IIC, and IIIA-IIID, which are classified followed the naming standard that has been specified by Makarova KS and Koonin EV [5]. Pairwise distances among the 93 cas1 protein sequences were calculated (https://github.com/rdpstaff/Clustering), and a cas1 protein tree was built by FastTree [32]. Together with the reference genome set, a genome of Streptomyces coelicolor (NC_003888.3) with a gene encoding transposase, a homolog of cas1 protein [33], was included as the outgroup to root the cas1 protein tree and also used to detect potential false positives in the following evaluation step.

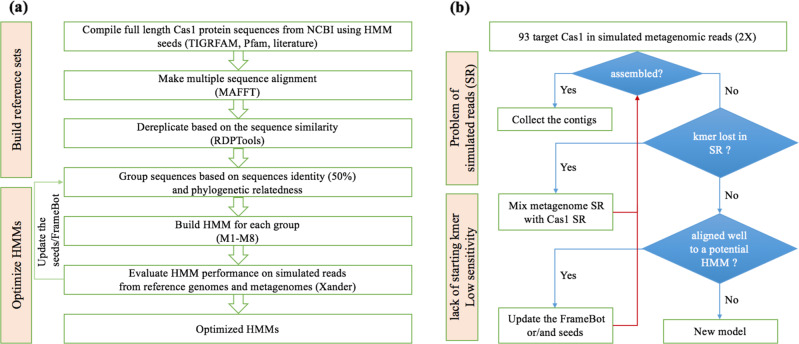

Fig. 1. The procedures of HMM construction and model optimization.

HMM construction (a): near full length of cas1 protein sequences previously used in Cas1 TIGRFAM, Pfam and mentioned in the literature were retrieved from NCBI and were cluster at 50% sequence identity after aligned by MAFFT and dereplicated by RDPTools. Eight HMMs were constructed based on the seed sequences in each cluster. Model optimization (b): the HMM performance was evaluated by the simulated reads generated from a set of reference genomes carrying 17 subtypes of CRISPR-Cas systems. We optimized the HMMs by updating the coverage of the corresponding seed sequences and Framebot files.

First, we used the reference genome set to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the eight HMMs. Simulated metagenomic reads from the 91 genomes were generated by an amplicon and shotgun sequence simulator, Grinder [34], starting with a 2× coverage of each genome. The simulated metagenome was then fed to Xander with the eight Xander packages to assemble cas1. The assemblies were then subjected to chimera check by Xander. The HMM sensitivity was assessed by whether all the 17 subtypes of cas1 can be recovered from the simulated metagenome using the targeted-assembly method. The HMM specificity was evaluated by accurate mapping of the targeted-assembled nucleotide sequences to the cas1 coding region of the designated genome from the reference genome set using Bowtie2 [35]. The respective cas1 protein sequences were also searched against nr database (NCBI) by BLAST [36] to check the assembly accuracy.

Second, the curated reference genome set can better improve the performance of the eight HMMs within the Xander packages. We first confirmed that the cas1 sequences of the reference genomes were covered in the simulated metagenome by checking if at least two 45-mer of the reference cas1 was in the kmer set of simulated reads (Fig. 1b). For the reference cas1 that contributed to the simulated reads but was not captured by any of the preliminary models, we aligned the corresponding protein sequence of the reference cas1 to the eight HMMs and added it to the seeds and framebot.fa of the best aligned HMM to enhance the sensitivity and the recovery of cas1 diversity (Fig. 1b).

Similar to the simulated metagenomes, the preliminary assemblies of cas1 proteins from the Oklahoma soil metagenomes mentioned below were also used to improve the performance of HMMs for targeted assembly. We searched the preliminary cas1 assemblies (though short and below the length threshold) against nr database (NCBI) by BLAST [36] and added the near full-length best hits into the corresponding seeds and framebot files to optimize the models.

After the iteration by updating the coverage of the seeds and framebot files (Fig. 1a) and reconstructing the HMMs, the eight final Xander packages contain more robust models, which are available at https://github.com/Ruonan0101/Targeted_Cas1_assembly. The processing steps are summarized in Fig. 1a.

Sequence trimming and targeted cas1 assembly from Oklahoma soil metagenomes

The Illumina adapters were removed from the paired-end reads using Trimmomatic v0.33 [37] (ILUMINACLIP). The trimmed reads were filtered for contiguous segments longer than 45 bases (same as the kmer length used in assembling) with the average quality score higher than 20 (SolexaQA++ v3.1.5 [38] dynamictrim and lengthsort). The trimmed sequences were fed to Xander [10] for targeted cas1 assembly. All eight cas1 HMMs, together with bacterial and archaeal ribosomal protein L2 (rplB) HMMs, were run simultaneously on each sample from the same bloom filter with the same kmer size of 45 since this larger kmer size can result in better assemblies with lower chimera occurrence. The length cutoff for cas1 protein sequences was set to 60 amino acids based on the lowest length coverage of cas1 subtype, which was IIID at 30.8% (Table 1). We kept rplB sequences longer than 150 amino acids. RplB was used rather than the 16S rRNA gene because it is a single copy ribosomal protein in all microbes and is well tested for assembly by Xander and taxonomic placement [39].

Table 1.

cas1 subtypes included in the training set, and subtype coverage and length recovered by each model.

| Subtype covered | No. of Cas1 included | Model | Average coverage (length) | Coverage (subtype) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IF | 8 | M1 | 92.3% | 100.0% | |||||||||||||

| IE | 20 | M2 | 86.2% | 100.0% | |||||||||||||

| CasY | 3 | M3 | 99.6% | 100.0% | |||||||||||||

| IIC/IIA/IIIA | 3/5/2 | M4 | 94.9% | 100.0% | |||||||||||||

| IA/IIB/IIIB/CasX | 5/2/2/1 | M5 | 59.0% | 100.0% | |||||||||||||

| Archaeal II | 1 | M6 | 99.4% | 100.0% | |||||||||||||

| IC/ID/IU/IIIC/IIID | 17/2/3/3/2 | M7 | 82.7% | 100.0% | |||||||||||||

| IB | 14 | M8 | 86.9% | 100.0% | |||||||||||||

| Cas1 subtypes | Archaeal II | CasX | CasY | IA | IB | IC | ID | IE | IF | IU | IIA | IIB | IIC | IIIA | IIIB | IIIC | IIID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average coverage (length) | 99.4% | 40.4% | 99.6% | 31.5% | 85.5% | 97.1% | 98.2% | 86.2% | 92.3% | 60.4% | 95.7% | 91.1% | 95.4% | 96.4% | 99.4% | 72.7% | 30.8% |

| Coverage (subtype) | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Contigs validation and host assignment to phylum level

Because the eight HMMs have overlapping specificity, we first dereplicated the combined assemblies from all eight models before predicting host taxonomy. All contigs from one sample were pooled together and searched against NCBI nr database. The top five hits with the descending bit scores of each contig were recorded together with the information of percent identity, coverage, accession number, and lineage. The best hit was selected only if the percent identity of the top hit was greater than the second one by 3% or it has the same host taxonomy with the remaining hits (phyla level used in the following data analysis), otherwise the contig was unclassified. The unclassified contigs kept the information of the best hit but with lineage noted as “unclassified.” All the classified and unclassified contigs were sorted based on accession numbers of the best hit to check the potential overlap between models. Contigs assembled by different models but with the same accession number of the best hit were re-examined and the ones with (1) classified lineage, (2) higher bit score, and (3) longer length were selected. The host of cas1 assemblies was assigned based on the taxonomy annotation of the screened hits.

Validation of assembly accuracy by comparing to the traditional annotation method

We leveraged de-novo assembled contigs obtained from Oklahoma grassland metagenomes to validate the assembly accuracy and evaluate the performance of the targeted method. The quality-filtered metagenomic reads were assembled by MegaHit [40] using kmer from 31 to 131 with step size of 20. The option of -kmin-1pass was used to recover low coverage species. There were 1,488,684 contigs with length longer than 1000 bp used for the following analysis.

We then applied the traditional cas1 annotation method by searching the ORFs predicted from all the de-novo assembled contigs using the eight HMMs. The ORFs annotated as putative cas1 via hmmsearch (HMMER, v3.1b2, http://hmmer.org/) were further validated by NCBI nr database. As both targeted and de-novo assembly methods can generate gene fragments, we only compared the numbers of cas1 sequences with near full length (>300 aa) from both methods to make a fair and conservative estimate of the performance.

Validation of host assignment method by comparing to the cas1-mapped de-novo assemblies

The reliability of cas1-based host assignment was tested by searching the targeted-assembled cas1 sequences against the de-novo assembled contigs using BLASTn. A qualified match was defined as a hit with (1) the highest bit score, (2) the percent identity greater than 95%, and (3) the length coverage higher than 50%. We predicted the taxonomies of de-novo assembled contigs via the Contig Annotation Tool (CAT) [41] with modifications. CAT assigned a de-novo assembled contigs with NCBI lineage based on multiple open reading frames (ORFs) predicted by Prodigal [42]. As cas1 is normally grouped with other CRISPR-Cas genes, which are more prone to horizontal transfer [1], we removed ORFs with NCBI annotations as CRISPR-Cas related proteins and fed CAT with filtered ORFs for taxonomy assignment. To check the sequence redundancy of cas1-mapped de-novo assembled contigs, we used the single linkage clustering to cluster the de-novo assembled contigs [43]. The detailed clustering method and results were in Supplementary File 1.

cas1 subtype assignment and prevalence estimation

As cas1 protein sequences were mostly grouped by subtype, we assigned the subtypes by placing the assemblies on the cas1 protein tree. The tree was built with the 93 cas1 protein sequences of 17 subtypes from the reference genome set using FastTree [32]. The cas1 assemblies filtered from the validation step were aligned to a reference HMM and the modeled positions were used to map to the branches of the cas1 protein tree via pplacer [44]. The cas1 contigs then adopt the subtype assignment of the mapped references.

cas1 abundance was adjusted by subtracting the abundance of the contigs assembled from the potentially overlapped models. The adjusted cas1 abundance detected in a microbial phylum was further normalized by the corresponding rplB abundance and noted as cas1 prevalence of a particular phylum in the following discussion.

Statistical analysis

Sequence distance matrix was calculated using RDPTools (Clustering) and plotted in R (v3.3.3, Vegan, pheatmap [45]). Canonical correspondence analysis including the cas1 host composition with environmental attributes was conducted by R (v3.3.3) with packages of Vegan [46] and ggplot2 [47].

Results

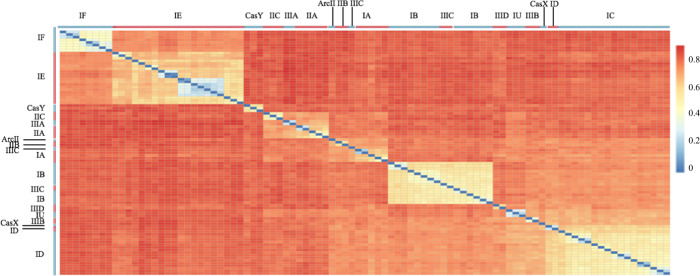

Targeted-assembly method provides a high coverage of cas1 diversity

To assess cas1 diversity, the pairwise distance of the 93 cas1 protein sequences belonging to 17 subtypes in the curated reference genome set (Fig. 2) was analyzed. The same subtype showed higher similarities but the distances within subtype can be up to 50–60%. The distance between different subtypes can be up to 80%. These revealed a high cas1 protein sequence diversity. Although HMMs are known to robustly detect remote protein homology [48], multiple HMMs were need to cover cas1 diversity. A limited (but sufficient) number of HMMs is preferred to avoid the potential coverage overlaps among models.

Fig. 2. Pairwise distances among cas1 protein sequences in the reference set of 91 genomes.

The designation of the 17 subtypes is shown. The scale of dissimilarity is from 0 to 1. The hotter color indicates a higher dissimilarity.

To test the coverages of the eight optimized HMMs implemented in Xander, we first assembled all the 17 subtypes of cas1 from the simulated metagenomes (Table 1). Generally, the eight HMMs have high average length coverages of targeted cas1 protein sequences (59–99% length coverage). Owing to the high diversity of some cas1 sequences, subtypes like CasX, IA, and IIID could be recovered by 30–40% of their length.

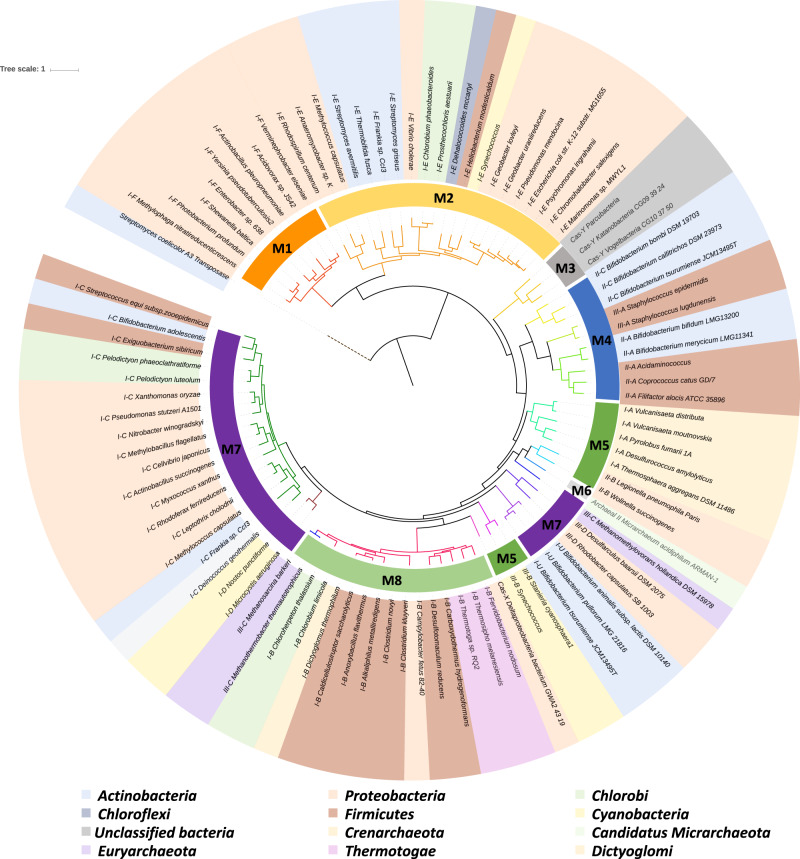

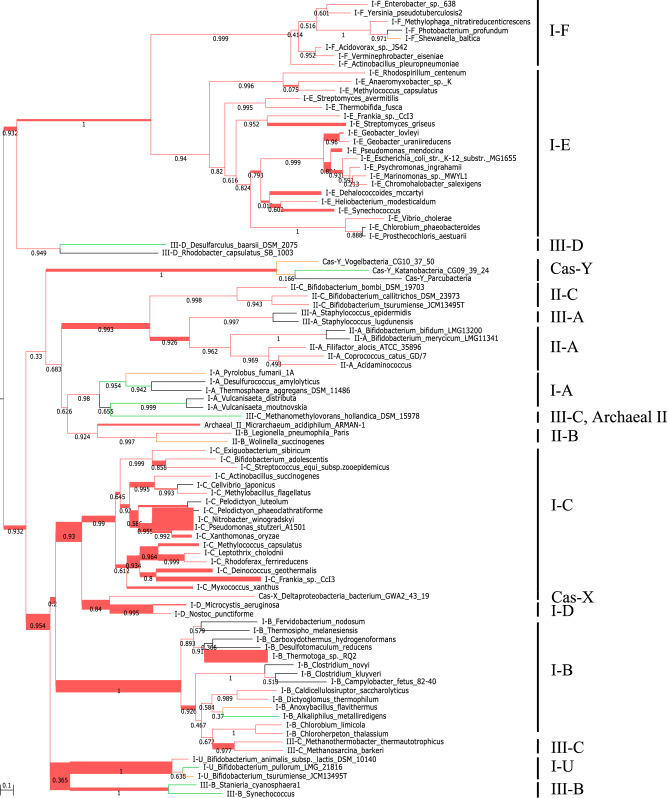

We built a cas1 protein tree (Fig. 3) to visualize the clustering of the different subtypes and potential coverage overlap among the eight models. cas1 protein sequences were clustered by subtypes and within each subtype, those from the same phylum generally clustered together (Fig. 3). Most of the models covered one clade except M5 and M7 (Fig. 3). cas1 protein sequences covered by M5 and M7 were both developed a deep subclade, which intersected with each other, implying potential overlap between models (Fig. 3). The Bowtie results (Supplementary T2) of the assemblies from the simulated metagenome generated from the reference genomes indeed showed some M7-assembled contigs were also captured by M5 but not the opposite. In this case, M7 always gave longer contigs. Length sorting was therefore incorporated in the contig validation step to remove the replicated assemblies resulting from the models with overlapping coverage.

Fig. 3. Rooted phylogenetic tree of cas1 protein sequences from the reference genomes.

Clades formed by 17 subtypes are colored differently. Model (M1–M8) coverages on different subtypes are shown in the inner circle and the taxonomy (phylum) of the host is displayed in the outer circle.

Targeted method increased the detection capacity and reliably resolved cas1 host community

To evaluate the performance of the targeted method and validate host assignment using the targeted-assembled cas1, we cross-checked cas1 annotated from contigs that were de-novo assembled from the Oklahoma soil metagenomes analyzed below.

Compared with 88 dereplicated near full length (greater than 300 amino acids) targeted cas1 assemblies, there were 17 near full length dereplicated cas1 genes from the de-novo assembled contigs (Supplementary T3). Nine of these matched targeted cas1 assemblies at greater than 99% nucleotide sequence identity. The other eight were distant to the known cas1 sequences, with between 45% and 83% amino acid identity to their closest cas1 BLAST matches. In comparison with the traditional method, the targeted method increased the detection capacity of recovering near full-length cas1 by five times (88 in targeted method versus 17 in traditional method). In addition, ~3300 targeted-assembled cas1 shorter than 300 amino acids were not included in this comparison but also contribute to cas1 diversity that can only be recovered by the targeted method.

The de-novo assemblies were also used to test the reliability of cas1 host assignment. We used BLAST to find contigs matching the targeted cas1 assemblies and found 147 de-novo assembled contigs with BLAST matches to 27 different targeted-assembled cas1. All but three of these have a match with greater than 99% nucleotide identity (Supplementary T4). These de-novo contigs could be dereplicated into 25 clusters with 100% amino acid pairwise identity between the shared ORFs, but for host assignment each contig was assessed individually. Among the 147 cas1-mapped de-novo assembled contigs, 110 (74%) could be assigned to host phyla using the CAT program after removing putative CRISPR-Cas genes. All the assignments agreed with the matching targeted-assembled cas1 assignment (Supplementary T4).

cas1 host community and subtypes in Oklahoma grassland microbiomes

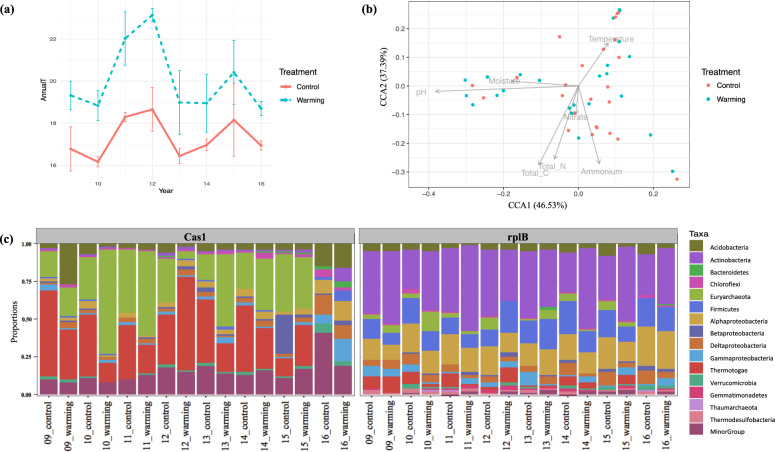

The 8-year continuous soil warming significantly increased the annual soil temperature above ambient by a mean of 2.38 °C with the largest increase of 4.16 °C, which occurred in the 4th year, 2012 (Fig. 4a). We targeted-assembled rplB and cas1 from 48 Oklahoma soil metagenomes with the average reads count of 1.0 × 108. The single copy core gene, rplB was used as a phylum-specific marker to estimate the microbial abundances and the major soil taxa were noted as the ones with rplB relative abundances greater than 1% (Fig. 4c, rplB). About 60% of the total cas1 counts were detected in the major phyla, suggesting cas1 was mainly distributed in the abundant phyla (Fig. 4c, Cas1). As noted above, cas1 was prevalent in Euryarchaota and Thermotogae (Fig. 4c, Cas1). cas1 host composition slightly changed in response to soil warming (Fig. 4c, Cas1). Besides temperature, cas1 host composition was under the impacts of nutrients (total carbon, total nitrogen, ammonium, and nitrate), pH and moisture (Fig. 4b). Diverse cas1 subtypes were detected in Oklahoma grassland microbiomes, i.e., 14 of the 17 subtypes (not IIIA, IIIB, and IIID) were found in both control and warming samples (Fig. 5). The cas1 subtype composition was not altered much when the soil was heated (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Increasing temperature with 8-year warming treatment and cas1 host composition.

Temperature fluctuation in warming and paired control treatment (a); canonical correspondence analyses (CCA) of cas1 host composition with the environmental attributes (b); cas1 host composition (c, left panel) and microbial composition revealed by rplB (c, right panel).

Fig. 5. Subtype annotation of cas1 protein assemblies from control and warming treatments.

cas1 protein sequences assembled from Oklahoma soil metagenomes with control and warming treatments were mapped to the branches of Cas1 reference tree that was constructed by 93 cas1 protein sequences with the verified subtypes specified on the right. The branches placed with cas1 protein sequences assembled from both control and warming samples are highlighted in red. The branches mapped by cas1 protein sequences from control or warming samples are colored in green and yellow, respectively.

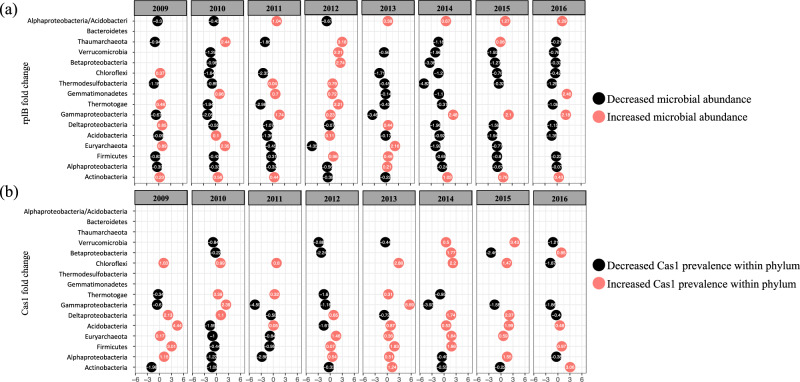

Change of rplB abundances and cas1 prevalence in each taxon under soil warming treatment

To assess the general dynamics of microbial communities in response to 8 years of soil warming, we calculated the fold changes of rplB abundance (Fig. 6a) and cas1 prevalence in major soil taxa (Fig. 6b). There was no gradual temporal pattern observed over the 8-year continuous warming. However, the rplB abundances of 9 out of 13 major taxa increased in 2012 when the soil warming effect reached a peak though it dropped thereafter (Fig. 6a). The ratio of rplB abundances of Alphaproteobacteria to Acidobacteria was included as an indicator of nutrient availability since Alphaproteobacteria are regarded as fast-growing and copiotrophic microbes in contrast to Acidobacteria, which are more generally oligotrophic. This ratio gradually increased after 2012 and doubled since 2015 (Fig. 6a). Moreover, cas1 prevalence tended to increase in warming plots after 2012, even in the taxa with decreased rplB abundances, such as Acidobacteria, Chloroflexi, Deltaproteobacteria, Euryarchaeota (Fig. 6b), suggesting a preference to CRISPR-Cas carrying microbes.

Fig. 6. Responses of microbial abundance (rplB) and cas1 prevalence within each major taxon (relative microbial abundance >1%) to 8-year soil warming treatment.

Fold change (log2) of rplB abundance of each major taxon (relative abundance >1%) (a) and the cas1 prevalence within the corresponding phyla (b) in response to the 8-years’ soil warming; All listed major taxa are arranged according to an ascending order of rplB abundances. The positive and negative values of log2 transformed fold changes are differentiated by red and black bubbles, respectively.

Discussion

Targeted-assembly method gives a high coverage of cas1 diversity and a reliable host assignment

The conventional approach to studying CRISPR-Cas subtype and host taxonomy is annotating the de-novo assembled contigs [6]. This largely limits the detection ability due to the incomplete assemblies from metagenomes with high sequence complexity such as in soil. To overcome this challenge, we constructed eight Cas1 HMMs to assemble the universal and most conserved Cas protein [1] directly from the metagenomes using Xander. The main advantages of this targeted approach are high coverage of cas1 sequence diversity, subtype classification, and reliable host assignment.

Targeted assembly using the eight HMMs provided a high coverage of the 17 subtypes of cas1 as validated with a simulated metagenome. This provides the opportunity to deeply mine the CRISPR-Cas system in more complex microbiomes. cas1 protein sequences generally clustered according to subtypes which were classified based on the organization of CRISPR-Cas system loci (Fig. 3) [5]. Therefore, the cas1 protein tree can be used as a template to place the cas1 protein assemblies and assign the subtypes.

In comparison with the traditional method of annotating cas1 on the contigs de-novo assembled from the Oklahoma soil metagenomes, the targeted method recovered five times more cas1 with near full length in addition to the another ~3300 shorter ones, which could be from the less abundant microbes. Analyzing the targeted-assembled cas1 could provide new opportunities to investigate the diverse CRISPR-Cas system. CRISPR arrays are reported to be horizontally transferred with Cas proteins homologous across different subtypes [49, 50]. No studies, however, specifically investigated the mobility of cas1 proteins. To validate the cas1-based host assignment to the phylum level, we compared the results of mapping the targeted-assembled cas1 to the de-novo assembled contigs from the Oklahoma soil metagenomes.

Only a small proportion of the targeted-assembled cas1 nucleotide sequences could be mapped to the de-novo assembled contigs and all were within the cas1 coding regions, highlighting that the targeted-assembly method can potentially better recover cas1 diversity with high assembly accuracy. None of the cas1-mapped de-novo assembled contigs (sans CRISPR-Cas-related genes) were assigned to a different host taxonomy by the targeted and de-novo assembly methods (Supplementary T4). This showed strong evidence that at least in Oklahoma grassland microbiomes, cas1 protein sequences were less mobile across phyla. This could be due to the high sequence diversity giving distinctive cas1 features and/or selective usage of CRISPR-Cas system by different phyla. The majority of cas1-mapped de-novo assembled contigs were annotated as Euryarchaeota and Thermotogae, which are also the two most dominant cas1 hosts (Fig. 4c, Cas1), although they were minor groups in the total microbial community (Fig. 4c, rplB). The targeted-assembly method can retrieve cas1 even from the less abundant microbes, providing more opportunities to uncover CRISPR-Cas ecology. Comparing with the de-novo assembled contigs is an important step to further validate the assembly accuracy and whether the gene of interest can inform the host taxonomy, especially when studying new habitats.

Effects of soil warming on cas1 subtypes and preference in Oklahoma grassland microbiome

rplB and cas1 were targeted-assembled from 48 metagenomes encompassing 8 years of continuous warming of a tallgrass prairie soil in Oklahoma to investigate the dynamics of microbial abundance and cas1 prevalence in response to soil warming. The microbial abundance of the major phyla increased in 2012 when the heating differential was the highest, and dropped back after 2012 (Fig. 6a). This may reflect a strong resilience of the soil microbiome at the phylum level. In addition, the microbial abundance ratio of Alphaproteobacteria to Acidobacteria after 2012 gradually rose and doubled after 2015. This ratio has been used to suggest nutrient availability in which fast-growing microbes like Proteobacteria are favored over slow-growing bacteria like Acidobacteria that are more successful in low nutrient environments [16, 17]. The increasing soil temperature may act as a trigger and slowly induce changes or sequential reactions affecting the other environmental factors, such as pH, moisture, carbon, and nitrogen [51], which may explain the strong negative correlations between soil temperature with pH, and pH with moisture and nitrogen (Supplementary Fig 1). cas1 host composition, as a result, could be influenced by a combined effect of temperature, pH and moisture, and nutrients (total carbon, total nitrogen, nitrate, and ammonium) (Fig. 4b). Although the overall microbial communities have an ability to recover after environmental perturbation, the warming effect may lead to changes of soil physiochemistry and slowly affect the microbe and cas1 host composition.

We detected a diverse but similar cas1 subtype composition in the warming samples and the paired controls. Therefore, there may be a microbial shift within a phylum carrying the same subtypes in response to soil warming. Our previous study at the same sampling site indeed revealed that this warming treatment led to an increasing divergence of microbial composition based on 16S ribosomal RNA genes [15]. A recent study has experimentally demonstrated that CRISPR-Cas systems can be shared between bacterial genera [52]. Replicating and passing the same mature CRISPR-Cas systems among the different and same genera within a phylum may be advantageous for microbial survival under environmental perturbation.

In addition to the need of detecting the CRISPR-Cas dynamics within phyla, CRISPR-Cas system was favored within different microbial taxa, especially in Euryarchaeota and Thermotogae at our study site. As a result, the total counts of cas1 mainly reflect the abundance changes of the cas1-predominant hosts. Therefore, we calculated the cas1 prevalence per phylum, which can reveal a preference of CRISPR-Cas system within each host phylum. The prevalence of cas1 in each taxon tended to increase in response to soil warming. In 2013, 8 out of 10 taxa were increased in cas1 prevalence, 7 out of 11 taxa in 2014, and 6 out of 9 taxa in 2015 while 4 out of 9 in 2016 (Fig. 6b). The prevalence of cas1 or CRISPR-Cas system within each taxon also increased in the other major taxa, even in those with decreased microbial abundances after the heating stimuli, such as in Acidobacteria and Firmicutes (Fig. 6a). These imply that CRISPR-Cas system became more preferred in the major taxa after the largest temperature differential, suggesting more intense interactions with the viruses after soil warming. The higher temperature could increase the virulence of soil phages and induce the release of free phages as more become lytic [53].

Here, we validated and applied the gene targeted-assembly method to detect the CRISPR-Cas subtype diversity and predict cas1 hosts. Although the soil microbiome is known to have strong resilience to environmental changes, increasing CRISPR-Cas preference was observed in response to 8 years of soil warming. Applying this new method to environmental samples can improve our understanding of the ecological outcomes, and potentially the role of CRISPR-Cas in nature.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Fig 1 Correlation of the environmental attributes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Institute for Cyber-Enabled Research at Michigan State University for supplying computational resources. This study was funded by the US Department of Energy Office of Science, awards DE-SC0010715 and DE-FG02-99ER62848; National Science Foundation Awards DBI-1356380 and DBI-1759892. RW was funded by a Hong Kong Ph.D. Fellowship.

Data availability

The shotgun metagenomic sequences have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information under the BioProject PRJNA533082. The cas1 assemblies were submitted to DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank as a Targeted Locus Study project under the accession KDDF00000000, PRJNA551292. The de-novo assembled contigs are available at https://iegst1.rccc.ou.edu/owncloud/index.php/s/mODjEsnzJ8Jxe3s. The eight Cas1 HMMs can be downloaded from Fungene website (http://fungene.cme.msu.edu) and Xander packages are available on GitHub, https://github.com/Ruonan0101/Targeted_Cas1_assembly.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41396-020-0635-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Marraffini LA. CRISPR-Cas immunity in prokaryotes. Nature. 2015;526:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature15386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burstein D, Harrington LB, Strutt SC, Probst AJ, Anantharaman K, Thomas BC, et al. New CRISPR-Cas systems from uncultivated microbes. Nature. 2017;542:237–41. doi: 10.1038/nature21059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horn H, Slaby BM, Jahn MT, Bayer K, Moitinho-Silva L, Forster F, et al. An enrichment of CRISPR and other defense-related features in marine sponge-associated microbial metagenomes. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1751. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorokin VA, Gelfand MS, Artamonova II. Evolutionary dynamics of clustered irregularly interspaced short palindromic repeat systems in the ocean metagenome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2136–44. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01985-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makarova KS, Koonin EV. Annotation and classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. CRISPR: methods and protocols; 2015. p. 47–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Zhang Q, Doak TG, Ye Y. Expanding the catalog of cas genes with metagenomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:2448–59. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayling M, Clark MD, Leggett RM. New approaches for metagenome assembly with short reads. Brief Bioinform. 2019. 10.1093/bib/bbz020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Ashelford KE, Day MJ, Fry JC. Elevated abundance of bacteriophage infecting bacteria in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:285–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.285-289.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danovaro R, Manini E, Dell’Anno A. Higher abundance of bacteria than of viruses in deep Mediterranean sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1468–72. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.3.1468-1472.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Q, Fish JA, Gilman M, Sun YN, Brown CT, Tiedje JM, et al. Xander: employing a novel method for efficient gene-targeted metagenomic assembly. Microbiome. 2015;3:32. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0093-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nunez JK, Lee ASY, Engelman A, Doudna JA. Integrase-mediated spacer acquisition during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Nature. 2015;519:193. doi: 10.1038/nature14237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schindlbacher A, Rodler A, Kuffner M, Kitzler B, Sessitsch A, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S. Experimental warming effects on the microbial community of a temperate mountain forest soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43:1417–25. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeAngelis KM, Pold G, Topçuoğlu BD, van Diepen LT, Varney RM, Blanchard JL, et al. Long-term forest soil warming alters microbial communities in temperate forest soils. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:104. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J, Xue K, Xie J, Deng Y, Wu L, Cheng X, et al. Microbial mediation of carbon-cycle feedbacks to climate warming. Nat Clim Change. 2012;2:106–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo X, Feng J, Shi Z, Zhou X, Yuan M, Tao X, et al. Climate warming leads to divergent succession of grassland microbial communities. Nat Clim Change. 2018;8:813–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong JB, Sun HB, Peng F, Zhang HY, Xue X, Gibbons SM, et al. Characterizing changes in soil bacterial community structure in response to short-term warming. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2014;89:281–92. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yergeau E, Bokhorst S, Kang S, Zhou JZ, Greer CW, Aerts R, et al. Shifts in soil microorganisms in response to warming are consistent across a range of Antarctic environments. ISME J. 2012;6:692–702. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston ER, Rodriguez RL, Luo C, Yuan MM, Wu L, He Z, et al. Metagenomics reveals pervasive bacterial populations and reduced community diversity across the Alaska tundra ecosystem. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:579. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xue K, Yuan MM, Shi ZJ, Qin Y, Deng Y, Cheng L, et al. Tundra soil carbon is vulnerable to rapid microbial decomposition under climate warming. Nat Clim Change. 2016;6:595. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arndt D. Oklahoma climatological survey. 2009. http://climate.ok.gov/index.php/climate. Accessed Jul 2009.

- 21.Xu X, Sherry RA, Niu S, Li D, Luo Y. Net primary productivity and rain‐use efficiency as affected by warming, altered precipitation, and clipping in a mixed‐grass prairie. Glob Change Biol. 2013;19:2753–64. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwala R, Barrett T, Beck J, Benson DA, Bollin C, Bolton E, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D8–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(D1):D290–301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haft DH, Selengut JD, White O. The TIGRFAMs database of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:371–3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR–Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:722. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. The basic building blocks and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:1392. doi: 10.1042/BST20130038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Zhang F. Diversity, classification and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2017;37:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makarova KS, Haft DH, Barrangou R, Brouns SJJ, Charpentier E, Horvath P, et al. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:467–77. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briner AE, Lugli GA, Milani C, Duranti S, Turroni F, Gueimonde M, et al. Gueimonde M, et al. Occurrence and diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems in the genus bifidobacterium. PloS ONE. 2015;10:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:511–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eddy SR. A new generation of homology search tools based on probabilistic inference. Genome Inf. 2009;23:205–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PloS ONE. 2010;5:e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krupovic M, Shmakov S, Makarova KS, Forterre P, Koonin EV. Recent mobility of casposons, self-synthesizing transposons at the origin of the CRISPR-Cas immunity. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8:375–86. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Angly FE, Willner D, Rohwer F, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. Grinder: a versatile amplicon and shotgun sequence simulator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–U54. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson M, Zaretskaya I, Raytselis Y, Merezhuk Y, McGinnis S, Madden TL. NCBI BLAST: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Suppl 2):W5–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox MP, Peterson DA, Biggs PJ. SolexaQA: at-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:485. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo J, Cole JR, Brown CT, Tiedje JM. Comparing faster evolving rplB and rpsC versus SSU rRNA for improved microbial community resolution. 2018. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/435099v2.full.

- 40.Li D, Luo R, Liu C-M, Leung C-M, Ting H-F, Sadakane K, et al. MEGAHIT v1. 0: a fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods. 2016;102:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Meijenfeldt FB, Arkhipova K, Cambuy DD, Coutinho FH, Dutilh BE. Robust taxonomic classification of uncharted microbial sequences and bins with CAT and BAT. 2019. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/530188v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Hyatt D, Chen G-L, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez-R LM, Gunturu S, Harvey WT, Rosselló-Mora R, Tiedje JM, Cole JR, et al. The Microbial Genomes Atlas (MiGA) webserver: taxonomic and gene diversity analysis of Archaea and Bacteria at the whole genome level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W282–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsen FA, Kodner RB, Armbrust EV. pplacer: linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:538. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kolde R, Kolde MR. Package ‘pheatmap’. R Package. 2015;1:7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J Veg Sci. 2003;14:927–30. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plötz T, Fink GA. Robust remote homology detection by feature based Profile Hidden Markov Models. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2005;4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Scholz I, Lange SJ, Hein S, Hess WR, Backofen R. CRISPR-Cas systems in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 exhibit distinct processing pathways involving at least two Cas6 and a Cmr2 protein. PloS ONE. 2013;8:e56470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makarova KS, Aravind L, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Unification of Cas protein families and a simple scenario for the origin and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Biol Direct. 2011;6:38. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alatalo JM, Jägerbrand AK, Juhanson J, Michelsen A, Ľuptáčik P. Impacts of twenty years of experimental warming on soil carbon, nitrogen, moisture and soil mites across alpine/subarctic tundra communities. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44489. doi: 10.1038/srep44489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watson BN, Staals RH, Fineran PC. CRISPR-Cas-mediated phage resistance enhances horizontal gene transfer by transduction. MBio. 2018;9:e02406–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02406-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shan J, Korbsrisate S, Withatanung P, Adler NL, Clokie MR, Galyov EE. Temperature dependent bacteriophages of a tropical bacterial pathogen. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:599. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig 1 Correlation of the environmental attributes.

Data Availability Statement

The shotgun metagenomic sequences have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information under the BioProject PRJNA533082. The cas1 assemblies were submitted to DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank as a Targeted Locus Study project under the accession KDDF00000000, PRJNA551292. The de-novo assembled contigs are available at https://iegst1.rccc.ou.edu/owncloud/index.php/s/mODjEsnzJ8Jxe3s. The eight Cas1 HMMs can be downloaded from Fungene website (http://fungene.cme.msu.edu) and Xander packages are available on GitHub, https://github.com/Ruonan0101/Targeted_Cas1_assembly.