Abstract

Objectives: The management of healthcare workers (HCWs) exposed to confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is still a matter of debate. We aimed to assess in this group the attack rate of asymptomatic carriers and the symptoms most frequently associated with infection.

Methods

Occupational and clinical characteristics of HCWs who underwent nasopharyngeal swab testing for the detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in a university hospital from 24 February 2020 to 31 March 2020 were collected. For those who tested positive and for those who tested positive but who were asymptomatic, we checked the laboratory and clinical data as of 22 May to calculate the time necessary for HCWs to then test negative and to verify whether symptoms developed thereafter. Frequencies of positive tests were compared according to selected variables using multivariable logistic regression models.

Results

There were 139 positive tests (8.8%) among 1573 HCWs (95% confidence interval, 7.5–10.3), with a marked difference between symptomatic (122/503, 24.2%) and asymptomatic (17/1070, 1.6%) workers (p < 0.001). Physicians were the group with the highest frequency of positive tests (61/582, 10.5%), whereas clerical workers and technicians had the lowest frequency (5/137, 3.6%). The likelihood of testing positive for COVID-19 increased with the number of reported symptoms; the strongest predictors of test positivity were taste and smell alterations (odds ratio = 76.9) and fever (odds ratio = 9.12). The median time from first positive test to a negative test was 27 days (95% confidence interval, 24–30).

Conclusions

HCWs can be infected with SARS-CoV-2 without displaying any symptoms. Among symptomatic HCWs, the key symptoms to guide diagnosis are taste and smell alterations and fever. A median of almost 4 weeks is necessary before nasopharyngeal swab test results are negative.

Keywords: COVID-19, Healthcare operators, Nasopharyngeal swab, Nosocomial transmission, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a previously unknown virus that recently jumped from an as yet unidentified animal host to humans and is responsible for causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1]. The virus has since spread worldwide from China, causing the first pandemic of the 21st century, disrupting healthcare services in the affected countries and exacting a terrible toll of human lives [2,3].

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are crucial actors in the pandemic. Indeed, they work in an emergency situation and are continuously at risk of being infected while also being in contact with the most fragile members of our society: those who need health assistance. It is therefore crucial to avoid infected HCWs, who will spread the disease. Unfortunately, it is still unclear which microbiologic investigations and procedures should be adopted in HCWs in COVID-19 settings, especially with regard to those exposed to confirmed cases of COVID-19 and at risk for infection.

To answer this question, we reviewed all the nasopharyngeal swab tests performed in HCWs exposed to confirmed cases of COVID-19 at the Foundation IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico located in Milan, the capital of Lombardy, a large Italian region affected by COVID-19 [4]. We assessed the frequency of positive tests among symptomatic and asymptomatic HCWs, and we evaluated the association between occupations, symptoms (type and number) and presence of infection. We also calculated the median time between the day of diagnosis (first positive test) and the day the test results became negative.

Methods

We collected occupational and clinical characteristics of all the consecutive HCWs who underwent nasopharyngeal swabbing for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 at the Foundation IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico from 24 February 2020 (the day after the first COVID-19 case occurred in a physician at our hospital) to 31 March 2020. For workers with a positive test result, we collected laboratory results as of 22 May to calculate the time to test negative.

We tested HCWs at risk for infection, which we defined as contact with a patient or another HCW with (or later diagnosed with) SARS-CoV-2 infection. All those at risk were, according to the internal protocol, identified and contacted by the hospital infection prevention unit, isolated at home and tested. HCWs were subdivided into physicians (including residents), nurses and midwives, healthcare assistants, health technicians and clerical workers, and technicians. All information was collected from the infectious disease notification form associated with each test. HCWs were defined as symptomatic if they manifested any of the following in the 14 days before test: fever, cough, dyspnoea, asthenia, myalgia, coryza, sore throat, headache, ageusia or dysgeusia, anosmia or parosmia, ocular symptoms, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting. For those without symptoms who tested positive as of 31 March, we verified through clinical records whether they developed symptoms thereafter. The study was approved by the ethical committee (368_2020bis) of our institution and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

SARS-CoV-2 detection

For virus detection, two different methods were used. The first used Seegene reagents (Seoul, Korea). RNA extraction was performed with the STARMag Universal Cartridge kit on a Nimbus instrument (Hamilton, Agrate Brianza, Italy), and amplification was performed by Allplex 2019-nCoV assay. The second method used a GeneFinder COVID-19 Plus RealAmp Kit (Osang Healthcare, Anyangcheondong-ro, Dongan-gu, Anyang-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) on an ELITech InGenius instrument (Turin, Italy). Both assays identify the virus by multiplex real-time reverse transcription PCR targeting three virus genes (E, RdRP and N).

Statistical analysis

We compared frequencies of positive tests according to selected variables by the chi-square test, adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated with a multivariable logistic regression model including as covariates gender, age and occupation, as well as having reported any symptom. We evaluated the discriminating ability of the number of reported symptoms in a univariate logistic model and assessed the performance of each of 11 groups of symptoms by fitting a multivariable logistic model containing all groups of symptoms. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated after these models. We calculated the time since first positive test until a negative test result by the Kaplan-Meier test. The log-rank test was used to evaluate the association of gender, age or symptoms with the median time to a negative test result. Statistical analysis was performed by Stata 16 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

In the period 24 February 2020 to 31 March 2020, a total of 1573 HCWs, 1010 women (64.2%) and 563 men (35.8%), underwent at least a first nasopharyngeal swab test for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1 ). Mean age was 44.5 years, and the majority (1104/1573, 70.2%) were physicians (including residents) or nurses/midwives. One third of women (343/1010) and one fourth of men (137/563) reported having had at least one symptom at the time of testing or thereafter. The majority (1224/1573, 77.8%) had only one test performed, while 350 (22.2%) of 1573 individuals had from two to seven tests. The overall frequency of workers with at least one positive test result was 8.8% (139/1573; 95% CI, 7.5–10.3%). The frequency of positive tests ranged from 8.0% (13/162, healthcare assistants) to 10.5% (61/582, physicians)—much higher than among clerical workers (5/137, 3.6%). Among HCWs with symptoms, the frequency of positive tests was 24.2% (122/503). At the time of the first positive test, 28 workers (20.1%) among the 139 with positive results reported no symptoms; of these, 11 developed symptoms in subsequent weeks. Therefore, over the whole period 24 February to 22 May, the frequency of positive test results among the 1070 asymptomatic HCWs was 17 (1.6%), and the final proportion of asymptomatic HCWs among those who tested positive was 17 (12.2%) of 139. The predictive role of occupation and the presence of symptoms were confirmed in the multivariable logistic model. The likelihood of a positive test result increased with the number of reported symptoms.

Table 1.

Association between selected variables and frequency of at least one positive test among 1573 healthcare workers tested for SARS-CoV-2 in Milan, Italy, during 24 February 2020 to 31 March 2020

| Characteristic | Workers |

Positive test |

p | ORa | 95% CIa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | % | ||||

| All | 1573 | 139 | 8.8 | — | — | 7.5–10.3 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 1010 | 82 | 8.1 | 0.18 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Men | 563 | 57 | 10.1 | — | 1.63 | 1.08–2.47 |

| Age | ||||||

| <30 years | 248 | 31 | 12.4 | 0.30 | 1.00 | Reference |

| 30–39 years | 387 | 33 | 8.5 | — | 0.62 | 0.34–1.11 |

| 40–49 years | 326 | 26 | 8.0 | — | 0.55 | 0.29–1.01 |

| 50–59 years | 444 | 35 | 7.9 | — | 0.58 | 0.32–1.05 |

| 60+ years | 168 | 14 | 8.3 | — | 0.63 | 0.30–1.33 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Physicians, including residents | 582 | 61 | 10.5 | 0.15 | 4.15 | 1.55–11.1 |

| Nurses, midwives | 522 | 44 | 8.4 | — | 2.54 | 0.94–6.84 |

| Healthcare assistantsb | 162 | 13 | 8.0 | — | 2.27 | 0.75–6.86 |

| Health technicians | 170 | 16 | 9.4 | — | 2.61 | 8.88–7.69 |

| Clerical workers, technicians | 137 | 5 | 3.6 | — | 1.00 | Reference |

| Any symptom | ||||||

| No | 1070 | 17 | 1.6 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 503 | 122 | 24.2 | — | 24.3 | 14.3–41.5 |

| No. of symptoms | ||||||

| 1 | 197 | 33 | 16.7 | <0.001 | 12.5 | 6.79–22.9 |

| 2 | 149 | 34 | 22.8 | 18.3 | 9.92–33.8 | |

| 3 | 108 | 36 | 33.3 | 31.0 | 16.6–57.8 | |

| 4–7 | 49 | 19 | 38.8 | 39.2 | 18.6–82.9 | |

The p values were calculated by chi-square test. Data for number of symptoms come from chi-square test for trend.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

From a multivariable logistic model including gender, age class, occupation and any symptom. Number of symptoms calculated by univariate logistic model (reference: no symptoms).

Includes biologists, radiology and laboratory technicians, psychologists, other health technicians.

All symptoms (excluding sore throat) were positively associated with test positivity, especially fever and taste and smell alterations (Table 2 ). In a multivariable model, the strongest predictors of a positive test result were taste and smell alterations (OR = 76.9) and fever (OR = 9.12), followed by myalgias, asthenia, ocular symptoms and dyspnoea (ORs ranging from 2.15 to 5.78). The AUC from the model including these six group of symptoms was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.79–0.87), similar to an AUC of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.82–0.90) when including all symptoms. Sore throat was negatively associated with positivity (OR = 0.30).

Table 2.

Association between selected symptoms and frequency of at least one positive tests among 1573 healthcare workers tested for SARS-CoV-2 in Milan, Italy, during 24 February 2020 to 31 March 2020

| Specific symptom | Workers |

Positive test |

p | ORa | 95% CIa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | % | ||||

| Cough | ||||||

| No | 1343 | 84 | 6.2 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 230 | 55 | 23.9 | — | 1.72 | 1.05–2.81 |

| Fever | ||||||

| No | 1368 | 61 | 4.5 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 205 | 78 | 38.0 | — | 9.12 | 5.61–14.8 |

| Sore throat | ||||||

| No | 1422 | 128 | 9.0 | 0.48 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 151 | 11 | 7.3 | — | 0.30 | 0.14–0.64 |

| Coryza | ||||||

| No | 1462 | 113 | 7.7 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 111 | 26 | 23.4 | — | 1.71 | 0.89–3.30 |

| Headache | ||||||

| No | 1485 | 115 | 7.7 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 88 | 24 | 27.3 | — | 0.75 | 0.38–1.48 |

| Myalgias | ||||||

| No | 1513 | 119 | 7.9 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 60 | 20 | 33.3 | — | 2.15 | 1.02–4.55 |

| Diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting | ||||||

| No | 1524 | 126 | 8.3 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 49 | 13 | 26.5 | — | 1.59 | 0.67–3.79 |

| Asthenia | ||||||

| No | 1526 | 117 | 7.7 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 47 | 22 | 46.8 | — | 3.72 | 1.74–7.92 |

| Ocular symptoms | ||||||

| No | 1537 | 126 | 8.2 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 36 | 13 | 36.1 | — | 2.49 | 0.90–6.85 |

| Dyspnoea | ||||||

| No | 1541 | 124 | 8.0 | 0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 32 | 15 | 46.9 | — | 5.78 | 2.39–14.0 |

| Taste and smell alterations | ||||||

| No | 1547 | 119 | 7.7 | <0.001 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Yes | 26 | 20 | 76.9 | — | 51.4 | 17.6–150 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The p values were calculated by chi-square test.

From a multivariable logistic model including all symptoms.

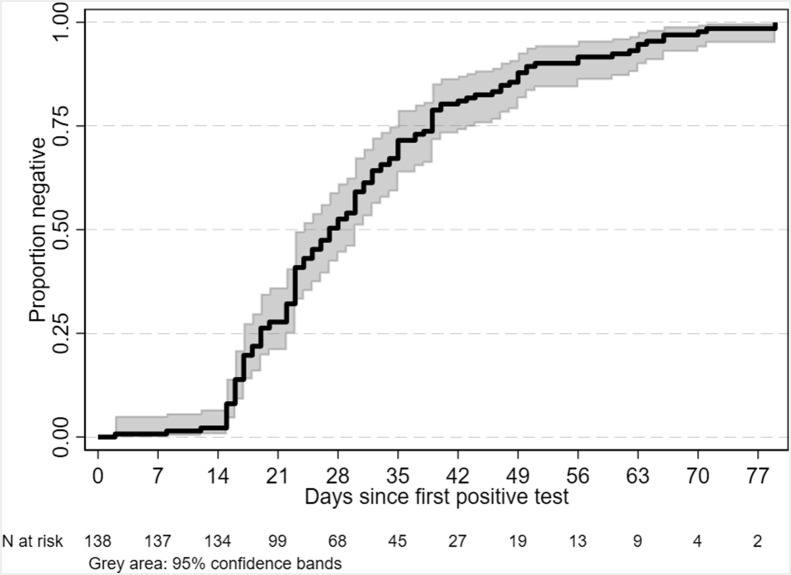

Among the 139 positive test results among HCWs, 100 (71.9%) had already tested positive at first testing, while 39 (28.1%) tested positive in a subsequent test. As of 22 May, all workers were test negative except for three who had not yet returned to work, and so did not have a control test performed. The rate of becoming test negative was almost null in the first 2 weeks, then started to rise at an approximately constant rate (Fig. 1 ). The median time from first positive test result to a negative result was 27 days (95% CI, 24–30) (Fig. 1). A total of 55 (39.6%) of 139 and 10 (7.2%) of 139 workers still had positive test results within 30 and 60 days, respectively. Median time was 1 week shorter in HCWs without symptoms (22 days; 95% CI, 15–30) than in those with symptoms (29 days; 95% CI, 24–31), but the p value from the log-rank test was high (p 0.91) as a result of the low number of asymptomatic workers. Median time was not associated with gender (p 0.96) or age (p 0.69). As of 22 May, eight workers, five men (three physicians and two nurses) and three women (two physicians and a clerical worker) were hospitalized.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier failure function showing times at which healthcare workers tested negative.

A minority of HCWs (81/1573, 5.1%) reported having had contact with an infected person outside the hospital (relatives, colleagues or friends). Of these, 12 (14.8%) of 81 had positive test results.

Discussion

In this Italian group of HCWs exposed to confirmed cases of COVID-19, the presence of symptoms—particularly taste and smell alterations and fever—was associated with positivity of nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2. Despite the low relative frequency of positive tests among asymptomatic workers, their number was high in absolute terms (one fifth of all those infected at the time of first positive test and about one eighth thereafter). Interestingly, the AUC of a model considering six groups of symptoms (fever, myalgia, asthenia, ocular symptoms, dyspnoea and taste and smell alterations) was 0.83. On the basis of these results, it seems reasonable to tailor the screening approach of HCWs at risk by using the resources available. In low-resource settings, we suggest focusing testing on those with symptoms to maximize efficacy, especially considering the continuous exposure of HCWs to at-risk situations, thus requiring repeated testing. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that in our study a nonnegligible number of workers were infected but displayed no symptoms, meaning that a fraction of those infected can be lost with a symptoms-based screening strategy. Therefore, in middle- and high-resource settings, mass screening for all HCWs exposed to confirmed COVID-19 cases appears to be the best approach to limit the spread of the virus. More detailed cost-effectiveness studies encompassing the epidemiologic context should be performed to define the optimal method.

The frequency of positive tests among symptomatic workers in our study population (24.2%) is similar to that reported by Keeley et al. [5] (18%) in their cohort composed of 1533 symptomatic HCWs presenting with fever plus one symptom among the following: cough, sore throat, runny nose, myalgia, headache and persistent cough. However, we note that focusing only on symptomatic HCWs results in missing many infected people. Indeed, we had 50 (36.0%) of 139 positive HCWs who had no symptoms or only one symptom. When we consider the overall frequency, our proportion of HCWs who tested positive (8.8%) is comparable to the 6% described by Kluytmans et al. [6] in a small Dutch cohort of HCWs, whereas it is far lower than the 38% reported by Folgueira et al. [7] in their Spanish cohort.

When stratified according to occupation, test-positive frequencies were clearly higher among subsets of workers with direct contact with patients (physicians including residents, nurses and midwives, healthcare assistants and health technicians) than those without (clerical workers and technicians). Consequently, careful screening of these groups of workers should be mandatory. No differences in terms of infection attack rate were seen between different age groups or between men and women, suggesting that risk factors for acquiring COVID-19 among HCWs are unrelated to age and sex.

Another relevant point is the high number of HCWs whose test results were negative at the first test but then positive when tested a second time. This might represent a serious concern, as a discrete fraction of these HCWs can further spread the virus unnoticed, thus hampering the efficacy of the screening strategy. It should be noted, however, that the second test was performed on a small number of operators, not on a routine basis, making these considerations subject to several potential biases. In addition, in a relevant proportion of our population, we could not retrieve information about the most likely date of exposure to a documented COVID-19 case. Thus, we cannot exclude a recent contact in which case the first test may have been performed too early (i.e. still in the incubation period, which has been estimated to be 5 days), before a sufficient amount of virus particles is detectable in the nasopharynx [8]. Moreover, it has to be considered that HCWs employed in COVID-19 units/hospitals are at risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure on a daily basis, and therefore repeated exposures, even unnoticed, can also occur after the first contact that motivated the test. Moreover, technical limitations may result in a falsely negative test: the sensitivity of nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2 detection has been estimated to be around 71% [9].

Finally, we observed a median time from first positive test to a negative test of 27 days. This is in accordance with several published reports, and it may have an impact on the efficiency of health systems [[10], [11], [12]]. Indeed, it means that infected HCWs will be unavailable to perform their duties for almost 4 weeks after their diagnosis. Our results were based on three-gene qualitative reverse transcriptase PCR. To understand the real significance of this virus detection, new studies are needed assessing the infectivity of virus particles and the possible impact of quantitative techniques.

Our study has some limitations. First, the surveillance system was set up quickly, in only a few days, as a result of the virus spread in our region since 20 February, when the first Italian case was identified in the south-east part of Lombardy. Therefore, the quality of the data was imperfect, and extensive, time-consuming data editing (through review of electronical records and, when necessary, paper forms) was required to retrieve and complete the relevant information. For the same reason, and because we wanted to provide a rapid response to concerns about virus spread in the hospital, we were forced to limit the analyses to only a part of the workforce, i.e. those first tested as of 31 March. Data revision as of 22 May was performed only for a subset of workers (those with positive test results and asymptomatic workers).

In conclusion, our results show that symptomatic HCWs exposed to confirmed cases of COVID-19 are almost 8 times more likely to be infected than asymptomatic HCWs. Nevertheless, a nonnegligible number of asymptomatic HCWs are also infected. Therefore, screening strategies should be tailored according to available resources. Taste and smell alterations and fever should be considered the most relevant symptoms suggesting a test ought to be performed. Finally, the median time to negative results of the nasopharyngeal swab test was almost 4 weeks. These results should be taken together with the mounting evidence showing that in many cases what is identified are noninfective virus particles, to find the best moment to perform surveillance nasopharyngeal swab testing.

Transparency declaration

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgements

We thank the personnel of the Virology Unit and SPIO (Servizio Prevenzione e Igiene Ospedaliera), F. De Palo, L. Guerrieri, L. Bordini, C. Nava, A. Lela, E. Radice, C. Mensi and L. Cariani, for their help in data collection and editing. The authors are also grateful to S. Villa for critical review.

Editor: L. Leibovici

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) 2019. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villa S., Lombardi A., Mangioni D., Bozzi G., Bandera A., Gori A. The COVID-19 pandemic preparedness or lack thereof: from China to Italy. Glob Heal Med. 2020;6:1–5. doi: 10.35772/ghm.2020.01016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) 2020. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020.https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cereda D., Tirani M., Rovida F., Demicheli V., Ajelli M., Poletti P. The early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.09320 arXiv.org, 20 March 2020.

- 5.Keeley A.J., Evans C., Colton H., Ankcorn M., Cope A., State A. Roll-out of SARS-CoV-2 testing for healthcare workers at a large NHS Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom, March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:1–4. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.14.2000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kluytmans M., Buiting A., Pas S., Bentvelsen R., van den Bijllaardt W., van Oudheusden W. SARS-CoV-2 infection in 86 healthcare workers in two Dutch hospitals in March. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.23.20041913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folgueira M.D., Muñoz-Ruipérez C., Alonso-López M.Á., Delgado R. SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers in a large public hospital in Madrid, Spain, during March 2020. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.07.20055723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang Y., Zhang H., Xie J., Lin M., Ying L. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang H., Hong Z. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1175–1177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y., Yan L.M., Wan L., Xiang T.X., Le A., Liu J.M. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;2019:2019–2020. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]