Dear Editor,

Acute respiratory syndrome (ARDS) is well documented as the primary manifestation of severe infection by the coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and is considered as the leading cause of death.1 However, emerging observations indicate severe SARS-CoV-2 infection should be regarded as a systemic disease involving multiple organs.2 This inflammatory state is associated with disturbances in the immune and hematopoietic systems.3 In this context, several laboratory findings related to severe inflammation, might be employed as biomarkers for monitoring disease severity, risk of complication and progression.4

Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a member of a family of neuronal growth factors that also includes nerve growth factor (NGF), Neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and NT-4/5. BDNF protein is synthesized as a 32 kDa pro-form (proBDNF) that is proteolytically cleaved to the 14 kDa mature form (mBDNF).5 BDNF has complex and incompletely verified peripheral sources; however, it has now become evident that BDNF is abundant in the peripheral blood,6 and different leukocyte subsets such as lymphocytes and monocytes were previously shown to produce and secrete BDNF.7

The effect of viral infection on peripheral BDNF levels that were previously studied show conflicting trends. One report indicated increased of BDNF and IL-6 under viral induced encephalopathy.8 In another study, viral infection with HIV resulted in reduced levels of BDNF in human lymphocytes.9 Blood levels of BDNF in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients were not reported yet. In this study we provide the first data on serum BDNF levels in SARS-CoV-2 patients and their correlations with clinical and laboratory indices of disease severity.

After obtaining approval from the institutional ethics committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, sixteen patients with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were recruited to this study. Serum samples were isolated upon hospital admission and at several time points during hospitalization. Disease severity was determined upon hospital admission and during hospitalization for each patient using the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2 calculator.10 Serum samples that were collected were stored in −30 °C for ELISA analysis. Other laboratory data that were recorded, included: total WBCs, absolute lymphocyte, platelets counts, C reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, D-dimmer and ferritin levels. Serum was thawed and diluted in phosphate buffered saline with 1% Bovine Serum Albumin. The total BDNF level in the diluted serum was quantified by the DuoSet ELISA Development System kit (R&D System DY278). BDNF concentration was calculated using an 8-point standard curve and multiplied by the dilution factor to achieve the fixed concentration in the serum. 2-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was used to compare BDNF levels in different clinical groups. A logistic regression model was used to test the correlation between BDNF levels and other continues variables. All statistical analyses and graphs were performed using JMP (SAS Inc.) statistical software.

Demographic details and variables of the patients are summarized in Table 1 . Nine patients (4 females and 5 males) had mild disease, 5 patients (5 males) determined with moderate disease and 2 patients (1 female and 1 male) had severe disease. One patient died (patient#13). There was no significant difference in mean age between patients with severe or moderate disease. Serum BDNF levels were normally distributed in patients (prob<W 0.56). Overall, we found significantly lower levels of serum BDNF in patients with severe or moderate disease as compared to patients with mild disease (6.3 ± 1.24 vs. 7.43 ± 2.31 ng/ml; p = 0.04). Patients with severe or moderate disease had significantly lower absolute lymphocyte count (1.18 ± 0.517 vs. 1.48 ± 0.46 × 103/µl; p = 0.04), higher CRP (77.56 ± 84.05 vs. 23.12 ± 29.66 mg/L; p = 0.007) and ferritin levels (691.47 ± 370.85 vs. 347.68 ± 235.79 ng/ml; p = 0.0009). In addition, we found a trend, albeit not significant, towards higher WBCs and lower platelets in patients with severe or moderate disease as compared to patients with mild disease. There was no difference in fibrinogen and D-dimmer levels.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and variables.

| Total participants: N | 16 |

|---|---|

| Gender: F:M (% of total) | 5(31.25) : 11(68.75) |

| Age (years): Mean ± SD (range) | 57.5 ± 17.5 (19–90) |

| WBCs (×103/µl) : Mean ± SD (range) | 6.27 ± 1.83 (3.2–10.68) |

| Lymphocytes abs (×103/µl) : Mean ± SD (range) | 1.32 ± 0.51 (0.48–2.36) |

| PLT (×103/µl) : Mean ± SD (range) | 259.72 ± 110.48 (100–605) |

| CRP (mg/L) : Mean ± SD (range) | 52.16 ± 69.62 (0.8–277.7) |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) : Mean ± SD (range) | 579.02 ± 185.76 (53–1174) |

| D-dimmer (ng/ml) : Mean ± SD (range) | 1338.37 ± 2992.92 (12.31–19,452) |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) : Mean ± SD (range) | 535.20 ± 357.93 (42.98–1685) |

| Serum BDNF (ng/ml): Mean ± SD (range) | 6.85 ± 1.97 (2.88–11.03) |

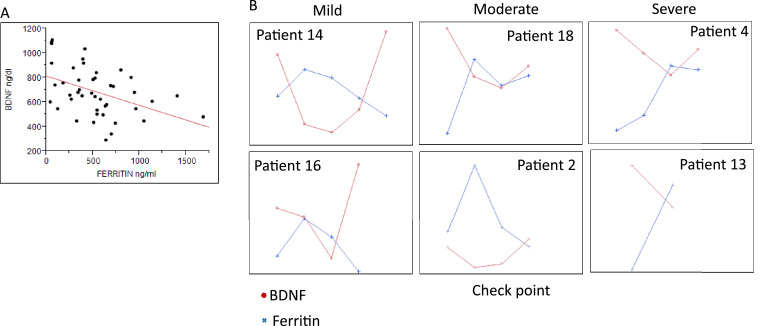

A logistic regression model was used to test the correlation between BDNF levels and other laboratory data. We found a significant inverse correlation only between BDNF levels and ferritin levels (r = −0.42, p< 0.003) (Fig. 1 a). Further analysis within patients, showed an opposite trend between BDNF and Ferritin levels with a trend of BDNF restoration through patients' recovery (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

BDNF and Ferritin levels in SARS-CoV-2 patients. a. A Linear regression between BDNF and Ferritin levels (r = −0.42, p< 0.003). b. BDNF (ng/dL) (red line) and Ferritin (ng/ml) (blue line) levels upon hospital admission (left check point) and at several time points during hospitalization and hospital discharge (right check point) in selected individual patients.

In our study, low serum BDNF levels were found to be correlated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, during patient's recovery, BDNF levels were restored. These data suggest that serum BDNF may serve as a biomarker for disease severity and for assessing the patient's clinical course. Our study confirms previous reports indicating the prognostic potential of Lymphopenia11 and the high levels of acute phase reactants such as CRP and ferritin in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.12 The contribution of lymphocytes BDNF secretion to the circulating pool, demonstrated in our earlier work,6 may link between the lymphopenia and the low BDNF observed in patients with severe disease.

Severe SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with an uncontrolled and over-production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e. “cytokine storm").3 The kinetics of BDNF in this study may be explained by previous reports indicated the suppressive effect of pro-inflammatory states on BDNF levels and function.13 To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first data on serum BDNF levels in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients and their correlations with clinical and laboratory indices of disease severity. However, this study is limited because of its low patient number. Therefore, further studies are needed to verify the interplay between ferritin and BDNF, and the potential using of BDNF as a biomarker in SARS-CoV-2 patients.

Funding sources

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- 1.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M., Wu X., Zhang L., He T. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. Hlh across speciality collaboration UK: COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen G., Wu D., Guo W., Cao Y., Huang D., Wang H. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620–2629. doi: 10.1172/JCI137244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binder D.K., Scharfman H.E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Growth Fact. 2004;22(3):123–131. doi: 10.1080/08977190410001723308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azoulay D., Vachapova V., Shihman B., Miler A., Karni A. Lower brain-derived neurotrophic factor in serum of relapsing remitting MS: reversal by glatiramer acetate. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;167(1–2):215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azoulay D., Urshansky N., Karni A. Low and dysregulated BDNF secretion from immune cells of MS patients is related to reduced neuroprotection. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;195(1–2):186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morichi S., Yamanaka G., Ishida Y., Oana S., Kashiwagi Y., Kawashima H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and interleukin-6 levels in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of children with viral infection-induced encephalopathy. Neurochem Res. 2014;39(11):2143–2149. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avdoshina V., Garzino-Demo A., Bachis A., Monaco M.C., Maki P.M., Tractenberg R.E. HIV-1 decreases the levels of neurotrophins in human lymphocytes. Aids. 2011;25(8):1126–1128. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834671b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Q., Meng M., Kumar R., Wu Y., Huang J., Deng Y. Lymphopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis. 2020;96:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calabrese F., Rossetti A.C., Racagni G., Gass P., Riva M.A., Molteni R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a bridge between inflammation and neuroplasticity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:430. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]