Abstract

Background

The viral shedding duration of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has not been fully defined. Consecutive detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from respiratory tract specimens is essential for determining duration of virus shedding and providing evidence to optimize the clinical management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Research Question

What are the shedding durations of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the upper and lower respiratory tract specimens? What are their associated risk factors?

Study Design and Methods

A total of 68 patients with COVID-19 admitted to Wuhan Taikang Tongji Hospital and Huoshenshan Hospital from February 10, 2020, to March 20, 2020, were recruited. Consecutive SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection from paired specimens of nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) and sputum were carried out. The clinical characteristics of patients were recorded for further analysis.

Results

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected from NPSs in 48 patients (70.6%), and from sputum specimens in 30 patients (44.1%). The median duration of viral shedding from sputum specimens (34 days; interquartile range [IQR], 24-40) was significantly longer than from NPSs (19 days; IQR, 14-25; P < .001). Elderly age was an independent factor associated with prolonged virus shedding time of SARS-CoV-2 (hazard ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.01-2.93). It was noteworthy that in 9 patients, the viral RNA was detected in sputum after NPS turned negative. Chronic lung disease and steroids were associated with virus detection in sputum, and diabetes mellitus was associated with virus detection in both NPS and sputum.

Interpretation

These findings may impact a test based clearance discharge criteria given patients with COVID-19 may shed virus longer in their lower respiratory tracts, with potential implication for prolonged transmission risk. In addition, more attention should be given to elderly patients who might have prolonged viral shedding duration.

Key Words: COVID-19, nasopharyngeal swab, SARS-CoV-2, sputum, virus shedding

Abbreviations: CLD, chronic lung disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; Ct, cycle threshold; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range; NPS, nasopharyngeal swab; rRT-PCR, real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 1804

Since December 2019, an outbreak of pneumonia started in Wuhan, China, and gradually spread around the world. The pathogen has been identified as a novel enveloped RNA beta-coronavirus named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which has a phylogenetic similarity to SARS-CoV, and has now been designated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization.1 The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 vary diversely from asymptomatic infection to mild upper respiratory tract infection and even acute respiratory distress syndrome.1, 2, 3, 4 Even though COVID-19 in China has been temporarily contained through proactive public health interventions including early detection and quarantine, it has rapidly spread to cause a pandemic around the world. Up to June 9, 2020, the global number of laboratory-confirmed cases had been > 7 million, highlighting that COVID-19 poses a substantial threat to international health.

Characterizing the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 is important for disease control and prevention. The duration of viral shedding, which has been recognized as a proxy measure of the infectious period for other respiratory viruses,5 , 6 is a current consideration with SARS-CoV-2. Hence, it is of urgent need to elucidate the viral shedding duration among patients with COVID-19 to optimize public health management policy.

COVID-19 is an infectious disease that is transmitted mainly through the respiratory tract. Therefore, consecutive detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from respiratory tract specimens using real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) with approximate sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 95%7 is crucial for defining virus shedding duration and may impact clinical decisions on a patient's discharge from the hospital and whether isolation and surveillance is required depending on infection control recommendations in a particular country. Nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) has been widely used for diagnosis and dynamic observation of patients with COVID-19 on account of its ease of acquisition. Two consecutive negative detections of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in NPS specimens have been recognized as criterion for discharge from hospital or release from quarantine.8, 9, 10, 11 Nevertheless, one limitation of NPS is the possibility of false-negative results, raising the concern that persistence of viral shedding might be present in the lower respiratory tract.12

Sputum has been reported to be more sensitive than NPS in SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection because SARS-CoV-2 mainly bind with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor of the lower respiratory tract.13, 14, 15 However, the use of sputum specimen in clinical practice is quite limited because only a proportion of patients with COVID-19 produce sputum spontaneously. Induced sputum is a convenient option to get lower respiratory tract samples and Han et al10 proposed in a case report that SARS-CoV-2 RNA could be detected more readily in a sputum specimen than in an upper respiratory tract specimen. The risk of medical staff exposure to COVID-19 is lower with sputum induction than with BAL methods; however, BAL fluid has exhibited a higher positive rate compared with nasal and pharyngeal swab samples.13 , 16 However, the SARS-CoV-2 detection yield and distinct virus shedding duration between sputum and NPS remain unclear.

We conducted a prospective cohort study of 68 hospitalized patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 by consecutively monitoring SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection from paired specimens of NPS and sputum aiming to identify viral shedding duration in the upper and lower respiratory tract specimens and to investigate possible factors associated with prolonged viral presence.

Methods

Data Collection

A cohort of 68 patients hospitalized (including ICU and non-ICU) in Wuhan Taikang Tongji Hospital and Huoshenshan Hospital were prospectively recruited from February 10, 2020, to March 20, 2020. They were all patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 according to the seventh edition of the Chinese Clinical Guidance for COVID-19 Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment,11 with specific clinical symptoms and radiologic abnormalities and two sequential positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA tests or specific serum IgM and IgG antibodies of SARS-CoV-2. Demographic information, clinical indexes, underlying diseases, treatment, and outcome data were extracted from electronic medical records using a standardized data collection form. This study was approved by the ethics commission of Shanghai East Hospital, China, and informed consent was obtained from participants.

The CURB-65 score was determined on the day of admission according to clinical criteria (confusion, urea > 7 mmol/L, respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/min, either diastolic BP ≤ 60 mm Hg or systolic BP < 90 mm Hg, age ≥ 65 years) defined by the British Thoracic Society.17

rRT-PCR Assay for SARS-CoV-2 in Respiratory Samples

Both NPS and sputum specimens were collected every 1 to 2 days after admission for detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using rRT-PCR until two sequential negative results were obtained. Briefly, induced sputum was obtained after inhalation of 10 mL of 3% hypertonic saline through a mask with oxygen at a flow rate of 6 L/min for 20 min, if patients did not have sputum; tracheal aspirates sputum was collected through aspiration with a sterile catheter if patients were intubated. The SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR assay was developed by Master Biotechnology with primers and probes targeting the N and Orf1b genes of SARS-COV-2 and applied in the laboratory of Taikang Tongji Hospital and Huoshenshan Hospital. Respiratory specimens with cycle threshold (Ct) values < 37 were considered positive for SARS-CoV-2, and those with Ct values ≥ 37 underwent repeat testing. On repeated testing, respiratory specimens with Ct values < 40 were considered positive for SARS-CoV-2, and those with Ct values ≥ 40 or with undetectable results were considered negative. We defined the interval between symptom onset and the date of the first SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative result for respiratory samples including both NPS and sputum specimens as the shedding duration.

Antibody Detection

Serum samples were detected for IgM/IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 using the colloidal gold immunochromatography antibody detection kit (Innovita Biological Technology Co, Ltd). Briefly, the serum samples were first incubated at 56°C for 30 min to heat-inactivate viruses, and then added into the sample well of the testing plate. After addition of reaction buffer and incubation for 10 to 15 min at room temperature, the testing result could be achieved and interpreted according to the instructions.

Statistical Analysis

The measurement data of normal distribution were presented as mean ± SD and compared by t test or analysis of variance, whereas the measurement data of nonnormal distribution were expressed by median and upper and lower quartile spacing and compared by Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test. The categoric variables were presented as numbers and percentages and were compared by χ2 or Fisher exact test. The analyses of risk factors associated with detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA in NPS or sputum or both were conducted using 1-way analysis of variance or the χ2 test. To identify risk factors associated with the duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding, we used a Cox proportional hazards model that adjusted for baseline covariates. Outcome was defined as the time interval from symptom onset to SARS-CoV-2 RNA negativity in both NPS and sputum specimens. For this analysis, we censored patients if they never cleared SARS-CoV-2 RNA, or if they were discharged alive or dead before they had cleared SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Potential variables for analysis of prolonged duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding were as follows: sex, age, comorbidities, lymphocyte count, and treatment with steroids. A hazard ratio (HR) > 1 indicated prolonged viral RNA shedding. In multivariable-adjusted Cox regression models, the HR was further adjusted for covariates including age and sex. We performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to estimate the cumulative SARS-CoV-2 RNA negativity rate among respiratory specimens and the stratified log-rank test to compare the difference of virus clearance between patients < 65 and ≥ 65 years of age. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 15 (StataCorp), and two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Overall, a total of 68 patients with COVID-19 who underwent consecutive SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection from NPS and sputum specimens were included: 36 (52.9%) were men and 32 (47.1%) were women. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1 . The median age of the patients was 67 years (interquartile range [IQR], 57-72). Fever was most commonly presented in 73.8% of the patients on admission (median maximum temperature, 38.5°C; IQR, 38.0°C-39.0°C), followed by cough (45.6%). Dyspnea (33.8%) and fatigue (32.4%) were also frequently observed, and diarrhea (10.3%) was less common. The median duration of fever, cough, and diarrhea was 11.0 days (IQR, 8.0-13.0), 20.0 days (IQR, 11.0-26.0), and 4.0 days (IQR, 2.0-5.0), respectively. Comorbidities were present in 39 patients (57.4%), with chronic lung disease (CLD) (17.6%) and diabetes mellitus (17.6%) being the most common underlying diseases, followed by cardiac disease (13.2%). On admission, 43 patients (63.2%) were diagnosed with COVID-19 based on positive NPSs, whereas 25 patients (36.8%) were diagnosed based on positive serum IgM/IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. During hospitalization, the overall positive rates of serologic tests for IgM and IgG against SARS-CoV-2 were 76.5% (n = 52) and 83.8% (n = 57), respectively. Regarding treatment, 30 patients (44.2%) required mechanical ventilation. Among them, five were intubated and the rest received noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation. High-flow nasal cannula and conventional oxygen support were used in 21 (30.9%) and 18 patients (26.5%), respectively. On admission, the severity of patients was evaluated by CURB-65 score: 30 patients (44.1%) had a score of 1, 36 patients (52.9%) had a score of 2, and two patients reached a score of 3. Meanwhile, the overall mortality of all patients was 4.4%.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of 68 Patients With COVID-19 (N = 68)

| Demographic and Clinical Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 67 (57-72) |

| Age ≥ 65 y | 40 (58.8) |

| Male | 36 (52.9) |

| Underlying diseases | |

| Chronic lung disease | 12 (17.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (17.6) |

| Cardiac disease | 9 (13.2) |

| Malignant tumor | 3 (4.4) |

| Clinical features | |

| Fever | 50 (73.5) |

| Temperature | 38.5°C (38°C-39°C) |

| Cough | 31 (45.6) |

| Dyspnea | 23 (33.8) |

| Fatigue | 22 (32.4) |

| Diarrhea | 7 (10.3) |

| Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 at admission | |

| By NPS (+) | 43 (63.2) |

| By IgM/IgG (+) | 25 (36.8) |

| IgM/IgG against SARS-CoV-2 during hospitalization | |

| IgM positive | 52 (76.5) |

| IgG positive | 57 (83.8) |

| Respiratory support | |

| NPPV | 25 (36.8) |

| HFNC | 21 (30.9) |

| Conventional oxygen therapy | 18 (26.5) |

| Intubation | 5 (7.4) |

| CURB-65 score | |

| 1 | 30 (44.1) |

| 2 | 36 (52.9) |

| 3 | 2 (2.9) |

| Duration of different symptoms in survivors, d | |

| Fever | 11.0 (8.0-13.0) |

| Cough | 20.0 (11.0-26.0) |

| Diarrhea | 4.0 (2.0-5.0) |

| Mortality | 3 (4.4) |

Values are No. (%) or median (interquartile range). COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; HFNC = high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy; NPPV = noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation; NPS = nasopharyngeal swab; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Distinct Yields of SARS-CoV-2 RNA Detection in NPS and Sputum Specimens

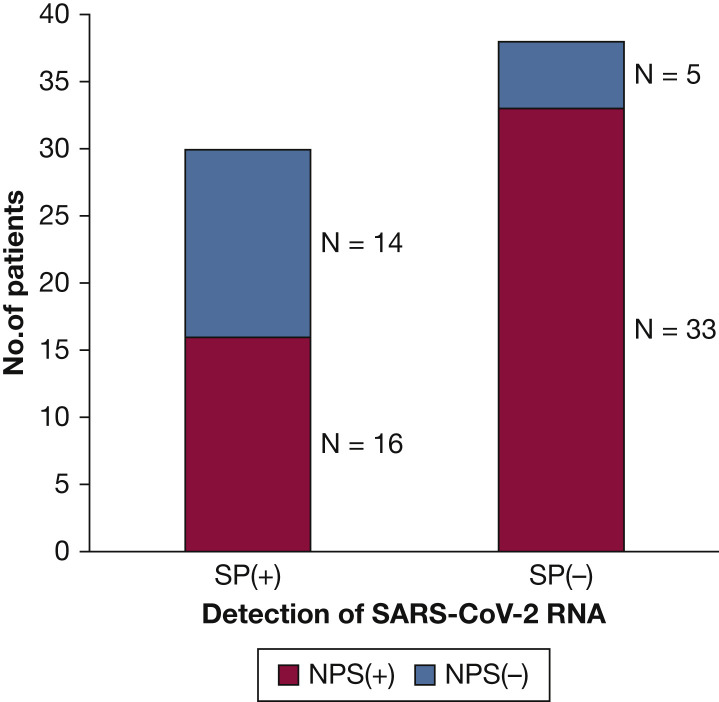

As shown in Figure 1 , of all 68 patients with confirmed COVID-19, 72.1% (n = 49) were identified with initial or follow-up positive NPS samples, 20.6% (n = 14) had initial and follow-up negative NPS samples paired with follow-up positive sputum specimens, and 7.4% (n = 5) had been diagnosed by serum IgM and IgG antibody assay while both NPS and sputum specimens remained negative during hospitalization.

Figure 1.

Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA in nasopharyngeal swab and sputum specimens from patients with coronavirus disease 2019 during hospitalization. NPS = nasopharyngeal swab specimen; SP = sputum specimen.

Meanwhile, 16 patients were detected with SARS-CoV-2 RNA both in NPS and sputum specimens, among whom further analysis was carried out to characterize the time interval between the last time of NPS positive and the first time of sputum positive. As shown in Figure 2 , nine patients had positive testing for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the sputum after NPS turned negative, six patients had positive sputum before NPS turned negative, and one patient had positive sputum on the day when NPS turned negative. The time interval ranged from 6 days before to 16 days after the NPS turned negative.

Figure 2.

Results of SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in 16 patients with both NPS and SP positive samples, by timing of first positive testing for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Day 0 is the day of first positive testing for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in each patient. D = day; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Factors Associated With Viral RNA Detection Yields of NPS and Sputum Specimens

We then explored the possible factors associated with the yields of NPS and sputum in detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The results showed CLD and systemic steroids use were associated with SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection from sputum, and diabetes mellitus was associated with viral RNA detection from NPS or sputum specimens. We further performed a sensitivity analysis in patients without CLD to take into consideration the possible effect of CLD on the association of systemic steroids with detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. There still existed a statistical difference in positive sputum rate between the steroids use group and nonsteroids use group (steroids use: 11 of 17; nonsteroids use: nine of 39; P = .003), which was consistent with the previous results. Besides, CLD was associated with both NPS and sputum positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Factors Associated With SARS-CoV-2 RNA Detection Yields in Nasopharyngeal Swab and Sputum Specimens During the Hospitalization

| Characteristics | NPS (+) (n = 49) |

NPS (−) (n = 19) |

P Value | SP (+) (n = 30) |

SP (−) (n = 38) |

P Value | NPS (+) and SP (+) (n = 16) |

Others (n = 52) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic lung disease | 8 | 4 | .646 | 10 | 2 | .003 | 6 | 6 | .017 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 | 7 | .010 | 9 | 3 | .018 | 3 | 9 | .895 |

| Fever | 35 | 15 | .398 | 25 | 25 | .103 | 14 | 36 | .147 |

| Cough | 23 | 7 | .452 | 13 | 17 | .908 | 7 | 23 | .973 |

| Fatigue | 16 | 6 | .932 | 9 | 13 | .712 | 6 | 16 | .615 |

| Diarrhea | 6 | 1 | .395 | 4 | 3 | .464 | 3 | 4 | .203 |

| Steroids | 12 | 8 | .153 | 13 | 7 | .025 | 7 | 13 | .150 |

| Lymphocyte numbers, mean ± SD | 0.88 ± 0.47 | 1.13 ± 0.75 | .721 | 0.99 ± 0. 47 | 1.14 ± 0.89 | .135 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | .517 |

Values are number of patients or as otherwise indicated. SP = sputum specimen. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

SARS-CoV-2 Shedding Duration and Risk Factors of Prolonged Viral Presence

The median duration of viral shedding from NPS and sputum specimens was 19 days (IQR, 14-25) and 34 days (IQR, 24-40), respectively (P < .001). By pooling together, the median duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding from either NPS or sputum specimens was 21 days (IQR, 16-31). Of 63 patients with rRT-PCR confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, only four patients (6.3%) had undetectable virus RNA within 8 days, 18 patients (28.6%) tested negative within 14 days, and 41 patients (65.1%) tested negative within 28 days after illness onset (Fig 3 ).

Figure 3.

A-C, Cumulative proportion of patients who had detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA by days after onset of illness: (A) from both NPS and SP specimens, (B) from NPS and SP separately, and (C) with age < 65 vs ≥ 65 y. See Figure 1 and 2 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

We further explored SARS-CoV-2 shedding duration and potential risk factors. In a multivariable model, elderly age (≥ 65 years) was identified as an independent factor associated with the viral shedding time in hospitalized patients (Table 3 ). SARS-CoV-2 RNA clearance was significantly delayed in patients ≥ 65 years of age compared with those < 65 years of age after onset of illness (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.12-2.93; P < .01) (Fig 3B).

Table 3.

Multivariable Analyses of Risk Factors Associated With Duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA Detection in Hospitalized Patients

| Characteristics | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 65y | 1.66 (0.99- 2.82) | .06 | 1.71 (1.01-2.93) | .04 |

| Sex, male | 1.04 (0.63-1.73) | .867 | 1.21 (0.69-2.13) | .50 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.57 (0.30-1.08) | .18 | 0.64 (0.31-1.29) | .21 |

| Chronic lung diseases | 0.72 (0.38-1.36) | .30 | 0.88 (0.40-1.97) | .76 |

| Lymphocyte counts | 1.01 (.083-1.23) | .91 | 0.98 (0.78-1.21) | .83 |

| Systemic steroids | 0.74 (0.41-1.32) | .30 | 1.08 (0.51-2.24) | .84 |

| Cardiac diseases | 0.59 (0.29-1.20) | .12 | 1.00 (0.45-2.27) | .99 |

| Hypertension | 0.61 (0.34-1.10) | .09 | 0.55 (0.26-1.16) | .76 |

| Malignant tumor | 0.23 (0.30-1.70) | .07 | 0.15 (0.16-1.49) | .11 |

HR, hazard ratio. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Adjusted for age and sex.

Recurrent Positive Detections of Viral RNA From NPS Specimens in Two Cases

We found two patients who had recurrent positive detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from NPS specimens (Fig 4 ) after serially negative tests. Case 1 was a 68-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus for 20 years. After nine consecutive negative NPS tests, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected again in NPS at day 29 after illness onset, whereas the sputum specimen tested positive serially six times from day 16 to day 29. Case 2 was a 55-year-old man with hypertension and cardiac disease. From day 9 to day 25 after illness onset, the patient had 11 consecutive negative NPS tests and seven consecutive positive sputum specimen tests, and then he had recurrent positive detection of virus RNA in NPS at day 25. These two cases continued to receive isolation and surveillance in hospital until NPS tests turned negative. When these two cases converted to NPS positive, they remained clinically stable without recurrence of symptoms and substantial changes in laboratory examinations.

Figure 4.

Illustrated information about two cases that had recurrent positive detection of SARS-COV-2 RNA from nasopharyngeal swab. d = day; DM = diabetes mellitus. See Figure 1 and 2 legends for expansion of other abbreviations.

Discussion

In this study, we found the median duration of SARS-CoV-2 shedding from either NPS or sputum specimens was 21 days and the median duration of viral shedding from sputum was significantly longer than from NPS. Age was identified as an independent risk factor of prolonged viral shedding time. Meanwhile, a combination of NPS and sputum specimens for detecting viral RNA could improve the diagnostic sensitivity. CLD and steroids use are associated with the detection of virus RNA from NPS, and diabetes mellitus is associated with the detection of virus RNA from both NPS and sputum specimens. In addition, it was noteworthy that in nine of 16 hospitalized patients where SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected both in NPS and sputum specimens, virus RNA could be detected in the sputum specimen after the NPS specimen turned negative.

Because coronavirus RNA detection is more sensitive than virus isolation by culture, most studies have used viral RNA tests as a potential marker to assess the potential transmission risk and to inform decisions regarding patients’ isolation. For Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome-COV, the duration of viral RNA detection in respiratory specimens was about 3 to 4 weeks after illness onset.18, 19, 20 Recently, Zhou et al21 reported that SARS-COV-2 RNA persisted for a median of 20 days in survivors and that is consistent with the findings from our present study. Additionally, we have found that age was an independent factor associated with prolonged SARS-COV-2 RNA shedding. Previously, it has been suggested that increased age was associated with mortality in SARS and MERS and may lead to death in patients with COVID-19.22 , 23 One possible reason for this is the age-dependent dysfunction of lymphocytes and the overproduction of type 2 cytokines.24 This could further result in slower viral clearance and prolonged shedding time.21

According to the Chinese guideline for COVID-19,11 the criteria for discharge were absence of fever for at least 3 days, substantial improvement in both lungs in chest CT scan, clinical remission of respiratory symptoms, and two throat swab samples negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA obtained at least 24 h apart.25 However, there is growing evidence showing that a certain number of discharged patients have tested positive during follow-up.9 In the present study, we describe two patients in detail who had a recurrence of detection of SARS CoV-2 virus RNA from NPS after previously converting to negative testing. The possible reasons for the relapse are multifold. First, COVID-19 is a novel coronaviral infectious disease; therefore, the clinical features and course are been fully understood. The pathogen of the disease is an RNA beta-coronavirus named SARS-COV-2, and mutation may occur during transmission, which could lead to ineffective antibodies produced by the recovered patients. If the discharged patient is reinfected by the mutated virus, the nucleic acid test may be positive again. Negative results may also occur if a patient still has very low levels of viral shedding, but their viral load is below the lower threshold of assay detection.

In this study, we found that viral RNA could be detected in sputum specimens after the NPS specimen turned negative, which was consistent with a previous report describing 22 patients with COVID-19 who had positive rRT-PCR results for SARS-CoV-2 in the sputum or feces after negative conversion of pharyngeal swabs.26 We also found that the duration of viral shedding in sputum specimens was longer than that in NPS. These findings may impact test-based clearance discharge criteria given patients with COVID-19 may shed virus longer in their respiratory tracts, with potential implication for prolonged transmission risk. Additionally, although not routinely recommended for initial diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2,27 induced sputum should be considered as an alternative for testing SARS-CoV-2 RNA when individuals are highly suspected of COVID-19 but nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal consecutively negative.

There are still several limitations to this study. First, the interpretation of our findings might be limited by its small sample size. Second, NPS specimens were obtained by different physicians, and this could have an impact on its detecting sensitivity. Third, lymphocyte subtypes and serum IgM/IgG antibody titers test were not performed. It was therefore not possible to determine the relationship between antiviral response and prolonged SARS-CoV-2 shedding. Finally, another limitation is that we detected virus by rRT-PCR instead of by virus isolation by culture. It is becoming more widely accepted that prolonged viral shedding may not indicate infectivity because rRT-PCR does not distinguish between infectious virus and noninfectious nucleic acid.28 In spite of this, relative cautious management strategies are still warranted for optimal transmission prevention, especially among vulnerable populations and health-care staff. Further studies are needed to determine whether individuals with prolonged positive NPS or sputum are infectious or not.

Interpretation

In patients hospitalized with COVID-19, the median duration of viral shedding from sputum specimens was significantly longer than from NPS. Elderly age was independently associated with prolonged SARS-CoV-2 shedding in the respiratory specimens. Viral RNA could be detected in sputum specimens after the NPSs became negative in some patients. These findings may impact test-based clearance discharge criteria given patients with COVID-19 may shed the virus longer in the lower respiratory tract, with potential implication for prolonged transmission risk. In addition, more attention should be given to elderly patients who might have prolonged viral shedding period. Besides, more studies are needed to determine whether prolonged viral shedding indicates infectivity of patients.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: X. W. is responsible for the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. T. S., Q. L., and X. W. conceived and designed the study. X. Zhang, J. S., F. Wang, J. Y., and J. H. coordinated to collect the data with technical guidance from X. W. K. Wang, X. W., H. Zhang, and T. S. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Drs K. Wang, X. Zhang, and Sun contributed equally to this manuscript. Drs T. Shi, Q. Li and X. Wu are corresponding authors and contributed equally to this manuscript.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant 81700006], the National Key R&D Program [Grant 2018YFC1313700], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant 81870064], and the “Gaoyuan” project of the Pudong Health and Family Planning Commission [Grant PWYgy2018-06].

References

- 1.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y., Guo Q., Yan Z. Factors associated with prolonged viral shedding in patients with avian influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2018;217(11):1708–1717. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsang T.K., Cowling B.J., Fang V.J. Influenza A virus shedding and infectivity in households. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(9):1420–1428. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson J., Whiting P.F., Brush J.E. Interpreting a covid-19 test result. BMJ. 2020;369:m1808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie X., Zhong Z., Zhao W., Zheng C., Wang F., Liu J. Chest CT for typical 2019-nCoV pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology. 2020:200343. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lan L., Xu D., Ye G. Positive RT-PCR test results in patients recovered from COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1502–1503. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han H., Luo Q., Mo F., Long L., Zheng W. SARS-CoV-2 RNA more readily detected in induced sputum than in throat swabs of convalescent COVID-19 patients. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):655–656. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30174-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chinese clinical guidance for COVID-19 pneumonia diagnosis and treatment (7th edition) http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202003/46c9294a7dfe4cef80dc7f5912eb1989.shtml Accessed March 4, 2020.

- 12.Winichakoon P., Chaiwarith R., Liwsrisakun C. Negative nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs do not rule out COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(5) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00297-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan Y., Shang J., Graham R., Baric R.S., Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94(7) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, Yang M, Shen C, et al. Evaluating the accuracy of different respiratory specimens in the laboratory diagnosis and monitoring the viral shedding of 2019-nCoV infections [published online ahead of print February 17, 2020]. medRxiv.https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.11.20021493

- 16.Liu R., Han H., Liu F. Positive rate of RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 4880 cases from one hospital in Wuhan, China, from Jan to Feb 2020. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;505:172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim W.S., van der Eerden M.M., Laing R. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58(5):377–382. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu D., Zhang Z., Jin L. Persistent shedding of viable SARS-CoV in urine and stool of SARS patients during the convalescent phase. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24(3):165–171. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-1299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh M.D., Park W.B., Choe P.G. Viral load kinetics of MERS coronavirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(13):1303–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1511695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau L.L.H., Cowling B.J., Fang V.J. Viral shedding and clinical illness in naturally acquired influenza virus infections. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(1):1509–1516. doi: 10.1086/652241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi K.W., Chau T.N., Tsang O. Outcomes and prognostic factors in 267 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(9):715–723. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong K.H., Choi J.P., Hong S.H. Predictors of mortality in Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) Thorax. 2018;73(3):286–289. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Opal S.M., Girard T.D., Ely E.W. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis in elderly patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 7):S504–S512. doi: 10.1086/432007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.China. Pneumonia diagnosis and treatment for COVID-19 infection. (trial version 7 revised version). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7652m/202003/a31191442e29474b98bfed5579d5af95.shtml. Accessed March 4, 2020.

- 26.Chen C., Gao G., Xu Y. SARS-CoV-2-positive sputum and feces after conversion of pharyngeal samples in patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(12):832–834. doi: 10.7326/M20-0991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html Accessed May 5, 2020.

- 28.Bullard J, Dust K, Funk D, et al. Predicting infectious SARS-CoV-2 from diagnostic samples [published online ahead of print May 22, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis.https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]