Abstract

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) accelerates epidermal regeneration, and it is widely studied as a wound-healing agent. However, the special carrier for the topical administration of EGF is urgently needed to deliver EGF on the wound site. In a preceding study, sacran hydrogel film (Sac-HF) showed a possible use as a dressing material for wound healing, as well as a good capability as a drug carrier. In the current study, we prepared Sac-HF containing EGF (Sac/EGF-HF) and then characterized their physicochemical properties, including thickness, swelling ratio, degradability, tensile strength, and morphology. In addition, we have also conducted thermal and crystallography studies using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and X-ray diffraction, respectively. Furthermore, we investigated the in vitro influence of Sac/EGF-HF on cell migration using a fibroblast cell line. Morphology study confirmed that the casting method used for the film preparation resulted in a homogeneous film of Sac/EGF-HF. Furthermore, EGF significantly increased the thickness, tensile strength, and degradability of Sac/EGF-HF compared to Sac-HF. Sac/EGF-HF had a lower swelling ability compared to Sac-HF; this result corroborated the tensile strength result. Interestingly, X-ray diffraction and DSC results showed that Sac/EGF-HF had an amorphous shape. The in vitro studies revealed that Sac/EGF-HF induced the fibroblast migration activity. These results conclude that Sac/EGF-HF has the potential properties of HF for biomedical applications.

Keywords: Epidermal growth factor, fibroblast migration, hydrogel film, sacran

INTRODUCTION

Human skin, the body's largest organ, has the three main roles, namely protection, regulation, and sensation of the body.[1] In everyday life, the skin can easily experience frictions which can cause wound injuries. The wound is the result of skin function disruptions on its anatomical and physiological normal conditions. At the time the wound occurs, the body responds with the four stages: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. At these stages, various kinds of growth hormones are released to promote wound healing, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor.[2]

The types of wound can be categorized into acute and chronic wounds. An acute wound can be totally healed in < 12 weeks.[3] Meanwhile, a chronic wound takes longer to heal compared to the acute wound, usually more than 12 weeks.[4] The healing of chronic wounds is troublesome, due to recurring of tissue damage or physiological conditions disorder, including diabetes, malignancy, chronic infections, poor hygiene, and other factors related to the patient.[5] Therefore, growth factors that accelerate wound healing are urgently needed. EGF is one of the essential growth factors, which affects the regeneration of the epidermis. Furthermore, EGF has been extensively observed as a wound-healing agent.[6,7,8] However, EGF can be easily degraded in the wound sites due to its proteolytic condition.[9]

To circumvent the above problem of degradation, many studies have been conducted to develop an effective EGF delivery system, improving its bioavailability and healing, such as dermal patches, nanofibers, and hydrogels.[10,11,12] Recent studies showed that hydrogel film (HF)-based natural polysaccharides could be used in the biomedical field as an excellent wound-dressing system due to its biocompatibility and low toxicity.[13,14,15] Three-component membranes of chitosan, hyaluronan, and a mitochondrially-targeted antioxidant-MitoQ demonstrated excellent wound-healing properties.[16] Ajovalasit et al. revealed that xyloglucan-based HFs are appropriate candidates for wound-dressing application.[17] Moreover, ionic cross-linking of alginate-pectin in HF improved the mechanical properties of HF.[18] Sacran, a mega molecular sulfate polysaccharide extracted from the extracellular jelly matrix of cyanobacterium Aphanothece sacrum, has a good characteristic biomaterial in HF for wound-healing process because of its high swelling ability and porosity, which can absorb more wound exudates and drug loading.[19,20] In the current study, we have prepared sacran hydrogel film (Sac-HF) comprising EGF (Sac/EGF-HF) and characterized their physicochemical properties. Then, we investigated the effect of Sac/EGF-HF on the migration of fibroblast cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Sacran was gifted from Green Science Material Inc. (Kumamoto, Japan) and EGF (sH-oligopeptide-1/synthetic human EGF) with purity >95% in ammonium sulfate solution was obtained from Skin Actives Scientific (Arizona, USA). Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and trypsin (TrypLE™) is a recombinant fungal trypsin-like protease were purchased from Merck (Jakarta, Indonesia) and Gibco (Jakarta, Indonesia), respectively. NIH3T3 cells were a kind gift from ProSTEM Indonesia (Jakarta, Indonesia). All other reagents were of analytical grade and used as received.

Preparation of sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

Sac-HF was prepared by the solvent-casting method as described in our previous study.[19] Sac-HF was inserted in Tissue-TekCryomold® (Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan). Then, 10 μl of EGFs (100 ng) in ammonium sulfate solution was placed and cast on the surface of the Sac-HF. The Sac/EGF-HF was kept for 24 h at 4°C in the dark condition and then dried for 4 h at 37°C.

Characterization of sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

Scanning electron microscopy analysis

Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF (1 cm × 1 cm) were coated by the platinum on the aluminum stub for 10 s (30 mM, 8 Pa). The surface of HFs was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (JEOL JSM-6510LA, Tokyo, Japan) in ×300 (50 μm, 15 kV).[19]

X-ray diffraction analysis

Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF (2.5 mm × 2.5 mm) were positioned on the specified X-ray diffraction (XRD) sample holder. XRD patterns were obtained in conditions of Ni-filtered Cu-Kα radiation, 40 kV, 20 mA, 10 mm diverging gap (0.5°), scanning speed 5°/min, opened scattering and receiving slit.[19]

Differential scanning calorimetric analysis

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) examination was performed using Auto Q20 (TA Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF were heated on the aluminum pan at a steady rate (10°C/min from 50°C to 300°C).[19]

Thickness study of sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

The thickness of Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF (1 cm × 1 cm) was measured using a dial thickness gauge (Teclock Corp., Nagano, Japan) in three random areas of HFs.[19]

Tensile strength of sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF (1 cm × 1 cm) were clipped with two holding grips; pulling force was applied by the top clip (0.5 mm/s) in Textechnofavigraph (Monchengladbach, Germany). Tensile strength was represented as the breakpoint of the HGFs for three times, and then, the average value was calculated by the tensile strength equation.

Tensile strength (MPa)

Where, P is a breaking force (the force needed for sample damage), b and d are the width and thickness of the sample, respectively.[21]

The swelling ratio of sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF (1 cm × 1 cm) were weighed (W0) and immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) for 24 h. Then, they were reweighed (Wt) at room temperature. The gravimetric method was used to calculate the swelling ratio (q) by comparing Wt and W0 (q = Wt − W0/W0).[22]

Degradability of sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel films

Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF (1 cm × 1 cm) were weighed (W0) and added with 2 ml (20%) of TCA and trypsin solutions for 24 h. Then, HFs were weighed as the final weight (Wt) and calculated the percent change in weight by the equation, percent in weight = 100 − (Wt/W0*100).[23]

Cell migration study

NIH3T3 cells were used to test the cell migration assay using the scratch method with slight modification.[24] Briefly, 24 well plates containing NIH3T3 cells culture (1 × 105 cells/well plate) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and 10% of fetal bovine serum were scratched with a sterile pipette tip and formed a straight line. NIH3T3 monolayer was washed with PBS to eliminate the cellular debris. Then, Sac-HF and Sac/EGF-HF were added to the plates. The migration of cells was monitored and photographed using the microscope at 0, 6, 12, and 18 h. The gap between migrating cells from the opposing wound edge at 0 h expressed as a percentage of the initial migration area. Then, the migration of cells was calculated by the following equation:[25,26]

At is the gap of the migration area measured at selected h.

A0 is the gap of the migration area measured at 0 h.

Data analysis

The results are presented as average ± standard error of the mean. Statistical evaluation was performed using the Scheffe's test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant between the group population.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Preparation of sacranhydrogel film and sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

In the preparation process of Sac-HF, heating at 80°C was conducted to form sacran solution. The solution was mixed by sonication to eliminate the air bubbles. The existence of bubbles in the solution will affect the thickness of HF. To acquire Sac-HF, the solution was heated at 60°C by evaporating the solvent. Furthermore, the heating process at 110°C is an important process because crosslinks between the sacran chains are formed by hydrogen bonding. Sacran has an annealing temperature between 70°C and 140°C, which affects the number of crosslinks.[20,27]

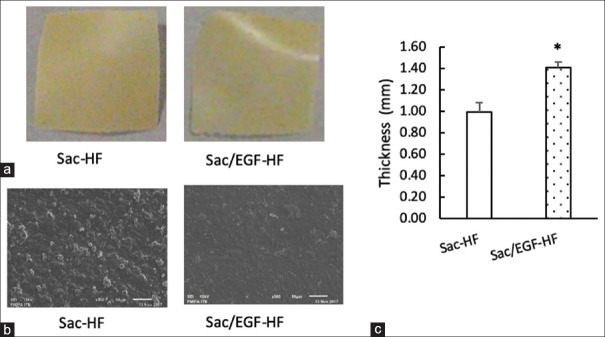

Figure 1a and b describe that Sac-HF and Sac/EGF-HF were successfully prepared with homogenous HF. Furthermore, there were no different shape and color between Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF in the macroscopic study. However, SEM results showed that Sac/EGF-HF was smoother than Sac-HF, indicating that EGF totally dissolved in Sac-HF. In our previous study, a combination of Sac-HF and water-soluble drug alike EGF can successfully form a homogenous HF.[28] A homogeneous condition is important to form Sac-HF with not only the equal thickness of HF but also the equal dose of EGF.[29]

Figure 1.

Appearances and thickness of Sac/EGF-HF (a) Macroscopic Appearances of Sac/EGF-HF (b) Microscopic Appearances of Sac/EGF-HF (c) Thickness of Sac/EGF-HF (a) The size of Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF was approximately in 1 cm × 1 cm (b) Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF were placed on an aluminum stub and coating it with platinum coater. The surface of HFs was analyzed by the SEM with × 300 (50 μm) (c) The thickness of Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF (1 cm × 1 cm) was measured by using a dial thickness gauge. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of three experiments. *P < 0.05, compared to Sac-HF. Sca/EGF-HF: Sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

Physicochemical characterization of sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

Previously, Sac-HF possessed the ideal properties as wound-dressing materials.[19] In the current study, we inspected the effect of EGF in the physicochemical properties of Sac-HF. First, the microscopic characteristics and surface homogeneity of Sac/EGF-HF were analyzed by the SEM. The morphology of Sac/EGF-HF was similar to that of Sac-HF [Figure 1b], indicating that EGF was incorporated and permeated into the Sac-HF forming homogenous HFs.

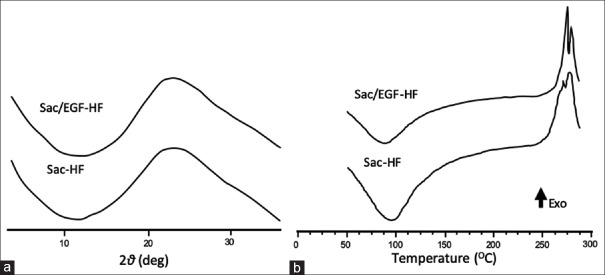

We, therefore, studied the crystallography of Sac/EGF-HF using XRD and DSC. As shown in Figure 2a, Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF had a similar pattern with no sharp peaks, representing the amorphous form. Thermal analyses by DSC are important to confirm the amorphous state. Furthermore, DSC testing is conducted to analyze the information about the characteristics of heat. Figure 2b confirms that Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF had a similar pattern without melting points. In addition, thermal analyses indicated that the exothermic peak in the area of 270°C–275°C represents a high degradation temperature, probably because sacran has a large molecular weight (2.9 × 10[7] Da). In addition, Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF had an endothermic peak at a temperature around 100°C, indicating the evaporation of water in Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF.[19] The DSC thermogram of Sac/EGF-HF did not show any melting points, indicating that Sac/EGF-HF was in the amorphous form. Amorphous HFs have been gaining attention in recent years owing to their high thermodynamic activity, thus accelerating drug diffusion and enhancing its solubility and bioavailability.[30,31]

Figure 2.

XRD and DSC Analyses of Sac/EGF-HF (a) XRD patterns of Sac/EGF-HF (b) DSC thermograms of Sac/EGF-HF (a) Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF (2.5 mm × 2.5 mm) were installed in the sample holder. XRD patterns were obtained in the specific conditions (b) Sac/EGF-HF and Sac-HF were heated on an aluminum pan, with a heating speed of 10°C/min from 50°C to 300°C. Sca/EGF-HF: Sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film, XRD: X-ray diffractometry, DSC: Differential scanning calorimetry

To determine the effect of EGF on the thickness of Sac-HF, the thickness of the Sac/EGF-HFs was examined. Figure 1c shows that the incorporation of EGF on Sac-HF significantly increased the thickness of Sac/EGF-HF compared to Sac-HF, suggesting that the EGF successfully incorporated in Sac-HF.[27]

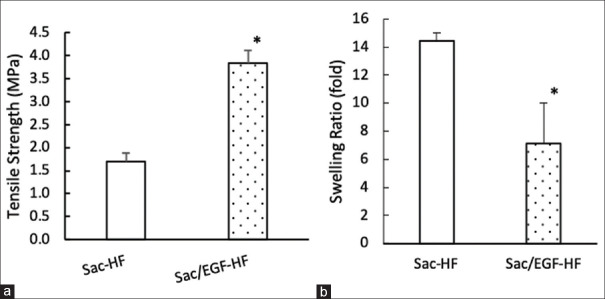

The mechanical strength of HFs provides the durability of HFs.[32] [Figure 3a] shows that the existence of EGF in Sac-HF significantly improved the mechanical strength of HFs compared to Sac-HF without EGF, suggesting that Sac/EGF-HF (3.8 MPa) was more durable than Sac-HF (1.7 MPa).

Figure 3.

Mechanical strength and swelling ratio of Sac/EGF-HF (a) Mechanical Strength of Sac/EGF-HF (b) Swelling ratio of Sac/EGF-HF (a) Tensile strength was done by placing hydrogel films on the sample holder with two holding grips and pulled by the top clip at a rate of 0.5 mm/s. Then, hydrogel films were analyzed by Textechnofavigraph (Monchengladbach, Germany) (b) Swelling ratio of Sac/EGF-HF was measured by the gravimetric method in PBS solution (pH 7.4) for 48 h. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of three experiments. *P < 0.05, compared to Sac-HF. Sca/EGF-HF: Sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film, PBS: Phosphate buffered saline

The addition of EGF in Sac-HF not only increased the properties of mechanical strength but also the thickness of HFs. Furthermore, the mechanical strength and swollen ratio of Sac/EGF-HF provided two opposite properties, and thereby it should be balanced through the optimal design. We speculated that EGF probably has a synergistic chemical interaction with sacran molecule. However, further extensive studies are necessary to fully understand this phenomenon.

Swelling ability in HFs is required to understand the effect of fluid absorption which correlates to the absorption of wound exudates.[32] Figure 3b shows that the swollen ratio of Sac-HF was up to 14.5 times, whereas Sac/EGF-HF was seven times. This result indicates that the addition of EGF decreased the swollen ratio of Sac-HF. In many cases, high hydrogel swelling ratio was related to low tensile strength.[33,34] In our previous study, the porous structure of Sac-HF was known to have great water absorption ability and played an important role in exudate wounds absorbing abilities.[32,35,36] The wound exudates contain many substances such as matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase, neutrophil elastase, and albumin.[35] Previous research showed that there was an increase of MMP-9 in acute and chronic wounds causing a decrease in wound-healing level, whereas the decrease of MMP-9 caused the increase of wound-healing level.[37,38,39,40,41,42]

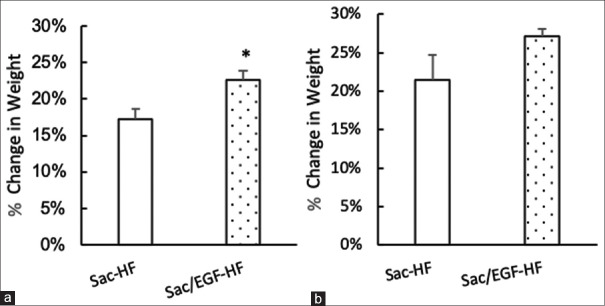

Degradability of sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

We next determined the effect of Sac/EGF-HF on the influence of chemicals (TCA) and the influence of enzymes (trypsin). The effect of HFs on TCA [Figure 4a] showed that the percent of weight change was not significantly different between Sac/EGF-HF and HF-Sacran. Instead, the effect of trypsin on HFs [Figure 4b] confirmed that Sac/EGF-HF had the percent of weight change (22.59%) considerably higher than that of Sac-HF (17.18%). The degradability study suggested that the degradation in the presence of trypsin enzyme could be ascribed to biocatalyst degradation. Therefore, polymer degradation in the presence of biocatalysts revealed that the polymer could be used as a good carrier for realizing the drugs.[23]

Figure 4.

Degradability Studies of Sac/EGF-HF (a) Effect of Sac/EGF-HF on TCA (b) Effect of Sac/EGF-HF on trypsin degradability studies were done by the gravimetric method in 20% of TCA or trypsin solutions, incubated for 24. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of three experiments. *P < 0.05, compared to Sac-HF. Sca/EGF-HF: Sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film, TCA: Trichloroacetic acid

Cell migration study

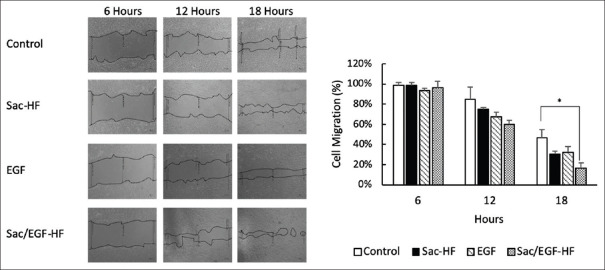

To investigate fibroblast migration, which significantly affects the wound-healing process, we clarified by the scratch method on NIH3T3 cells. Figure 5 represents the results of cell migration studies of Sac/EGF-HF. The cell migration at 6 and 12 h showed no significant different between all the groups. This result was in line with that of the previous proliferation studies. Interestingly, the cell migration of Sac/EGF-HF at 18 h was significantly higher than that of the control, suggesting that EGF in Sac-HF increased the cell migration ability of EGF alone or Sac-HF without EGF. The result of cell migration studies describes that the presence of EGF altered the migration speed at least at 18 h. This result is probably due to the prolonged release of EGF from Sac-HGF. Thönes et al. revealed that the sustained release of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor in hyaluronan/collagen hydrogels plays a crucial part in accelerating the wound healing of porcine skin.[43] However, the in vitro release of EGF is still unknown. Therefore, further studies regarding the release rate of EGF from Sac-EGS are required. Herein, Kim et al. proved that the addition of EGF enhanced the migration of aged fibroblasts.[44] In addition, recent studies revealed that EGF was biologically active in vitro and improved NIH3T3 cell proliferation in bell-shaped dose-response.[45,46] Therefore, Sac/EGF-HF is highly potential for wound-dressing application due to EGF role in fibroblasts, especially in the re-epithelization process by improving the production of collagen and stimulates cell renewal.

Figure 5.

Cell Migration Study of Sac/EGF-HF Sac/EGF-HF (1 mm × 1 mm) was added into 24 well-plates containing cell culture of NIH3T3 (1 × 105 cells/well). The space of cell migration was observed by using a microscope at the time of 0, 6, 12, and 18 h. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of three experiments. *P < 0.05, compared to Sac-HF. Sca/EGF-HF: Sacran/epidermal growth factor-hydrogel film

CONCLUSION

In the current study, we successfully prepared Sac/EGF-HF with homogeneous HF in an amorphous form. Moreover, Sac/EGF-HF had a better mechanical strength compared to Sac-HF. However, the existence of EGF in Sac-HF decreased the swelling ability of HF. Notably, the in vitro studies confirmed that Sac/EGF-HF significantly accelerated cell migration activity compared to control, suggesting that Sac/EGF-HF has the potential properties of HF for the biomedical application.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported by the fundamental research grant (grant number 751t/UN6.O/PL/2018) and Travel Grant Award 2020 from Universitas Padjadjaran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Shinichiro Kaneko, the CEO of Green Science Material, for affording sacran.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kanitakis J. Anatomy, histology and immunohistochemistry of normal human skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:390–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boateng JS, Matthews KH, Stevens HN, Eccleston GM. Wound Healing Dressings and Drug Delivery Systems. Wiley Intersci. 2008;97:2892–923. doi: 10.1002/jps.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Percival NJ. Classification of Wounds and their Management. Surg. 2002;20:114–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding KG, Morris HL, Patel GK. Healing chronic wounds. BMJ. 2002;324:160–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7330.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore K, McCallion R, Searle RJ, Stacey MC, Harding KG. Prediction and monitoring the therapeutic response of chronic dermal wounds. Int Wound J. 2006;3:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4801.2006.00212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown GL, Nanney LB, Griffen J, Cramer AB, Yancey JM, Curtsinger LJ, 3rd, et al. Enhancement of wound healing by topical treatment with epidermal growth factor. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:76–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907133210203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardwicke J, Schmaljohann D, Boyce D, Thomas D. Epidermal growth factor therapy and wound healing – Past, present and future perspectives. Surgeon. 2008;6:172–7. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(08)80114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi JK, Jang JH, Jang WH, Kim J, Bae IH, Bae J, et al. The effect of epidermal growth factor (EGF) conjugated with low-molecular-weight protamine (LMWP) on wound healing of the skin. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8579–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim H, Kong WH, Seong KY, Sung DK, Jeong H, Kim JK, et al. Hyaluronate-epidermal growth factor conjugate for skin wound healing and regeneration. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:3694–705. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b01216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alemdaroǧlu C, Deǧim Z, Celebi N, Zor F, Oztürk S, Erdoǧan D. An investigation on burn wound healing in rats with chitosan gel formulation containing epidermal growth factor. Burns. 2006;32:319–27. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hori K, Sotozono C, Hamuro J, Yamasaki K, Kimura Y, Ozeki M, et al. Controlled-release of epidermal growth factor from cationized gelatin hydrogel enhances corneal epithelial wound healing. J Control Release. 2007;118:169–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seonwoo H, Kim SW, Kim J, Chunjie T, Lim KT, Kim YJ, et al. Regeneration of chronic tympanic membrane perforation using an EGF-releasing chitosan patch. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:2097–107. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun J, Memon MA, Bai W, Xiao L, Zhang B, Jin Y, et al. Controllable fabrication of transparent macroporous graphene thin films and versatile applications as a conducting platform. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:4334–43. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao K, Chen T, Lin B, Cui W, Kan B, Yang N, et al. Adsorption and recognition of protein molecular imprinted calcium alginate/polyacrylamide hydrogel film with good regeneration performance and high toughness. React Funct Polym. 2015;87:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo Y, Diao H, Xia S, Dong L, Chen J, Zhang J. A physiologically active polysaccharide hydrogel promotes wound healing. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;94:193–204. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamer TM, Collins MN, Valachovaá K, Hassan MA, Omer AM, Mohy-Eldin MS, et al. MitoQ Loaded Chitosan-Hyaluronan Composite Membranes for Wound Healing. Materials (Basel) 2018;11:1–14. doi: 10.3390/ma11040569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ajovalasit A, Sabatino MA, Todaro S, Alessi S, Giacomazza D, Picone P, et al. Xyloglucan-based hydrogel films for wound dressing: Structure-property relationships. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;179:262–72. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rezvanian M, Ahmad N, Mohd Amin MC, Ng SF. Optimization, characterization, and in vitro assessment of alginate-pectin ionic cross-linked hydrogel film for wound dressing applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;97:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wathoni N, Motoyama K, Higashi T, Okajima M, Kaneko T, Arima H. Physically crosslinked-sacran hydrogel films for wound dressing application. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;89:465–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shikinaka K, Okeyoshi K, Masunaga H, Okajima MK, Kaneko T. Solution structure of cyanobacterial polysaccharide sacran. Polymer (Guildf) 2016;99:767–70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sezer AD, Hatipoğlu F, Cevher E, Oğurtan Z, Basş AL, Akbuğa J. Chitosan film containing fucoidan as a wound dressing for dermal burn healing: Preparation and in vitro/in vivo evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2007;8:1–8. doi: 10.1208/pt0802039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu A, Gwon K, Kim M, Tae G, Kornfield JA. Visible-light-initiated thiol-acrylate photopolymerization of heparin-based hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:497–506. doi: 10.1021/bm501543a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geesala R, Bar N, Dhoke NR, Basak P, Das A. Porous polymer scaffold for on-site delivery of stem cells – Protects from oxidative stress and potentiates wound tissue repair. Biomaterials. 2016;77:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botusan IR, Sunkari VG, Savu O, Catrina AI, Grünler J, Lindberg S, et al. Stabilization of HIF-1alpha is critical to improve wound healing in diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19426–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805230105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pratoomsoot C, Tanioka H, Hori K, Kawasaki S, Kinoshita S, Tighe PJ, et al. A thermoreversible hydrogel as a biosynthetic bandage for corneal wound repair. Biomaterials. 2008;29:272–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grada A, Otero-Vinas M, Prieto-Castrillo F, Obagi Z, Falanga V. Research techniques made simple: analysis of collective cell migration using the wound healing assay. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:e11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji D, Choi S, Kim J. A hydrogel-film casting to fabricate platelet-reinforced polymer composite films exhibiting superior mechanical properties. Small. 2018;14:e1801042. doi: 10.1002/smll.201801042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wathoni N, Motoyama K, Higashi T, Okajima M, Kaneko T. Enhancement of curcumin wound healing ability by complexation with 2-hydroxypropyl- g -cyclodextrin in sacran hydrogel film. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;98:268–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okajima MK, Mishima R, Amornwachirabodee K, Mitsumata T, Okeyoshi K, Kaneko T. Anisotropic swelling in hydrogels formed by cooperatively aligned megamolecules. RSC Adv. 2015;5:86723–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bigucci F, Abruzzo A, Saladini B, Gallucci MC, Cerchiara T, Luppi B. Development and characterization of chitosan/hyaluronan film for transdermal delivery of thiocolchicoside. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;130:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen NT, Liu JH. Fabrication and characterization of poly (vinyl alcohol)/chitosan hydrogel thin films via UV irradiation. Eur Polym J. 2013;49:4201–11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed EM. Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications: A review. J Adv Res. 2015;6:105–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anseth KS, Bowman CN, Brannon-Peppas L. Mechanical properties of hydrogels and their experimental determination. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1647–57. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)87644-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drury JL, Dennis RG, Mooney DJ. The tensile properties of alginate hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3187–99. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Power G, Moore Z, O'Connor T. Measurement of pH, exudate composition and temperature in wound healing: A systematic review. J Wound Care. 2017;26:381–97. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2017.26.7.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wathoni N, Motoyama K, Higashi T, Okajima M, Kaneko T, Arima H. Enhancing effect of γ-cyclodextrin on wound dressing properties of sacran hydrogel film. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;94:181–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tarlton JF, Bailey AJ, Crawford E, Jones D, Moore K, Harding KD. Prognostic value of markers of collagen remodeling in venous ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 1999;7:347–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.1999.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarlton JF, Vickery CJ, Leaper DJ, Bailey AJ. Postsurgical wound progression monitored by temporal changes in the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:506–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trengove NJ, Stacey MC, MacAuley S, Bennett N, Gibson J, Burslem F, et al. Analysis of the acute and chronic wound environments: The role of proteases and their inhibitors. Wound Repair Regen. 1999;7:442–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.1999.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ladwig GP, Robson MC, Liu R, Kuhn MA, Muir DF, Schultz GS. Ratios of activated matrix metalloproteinase-9 to tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in wound fluids are inversely correlated with healing of pressure ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10:26–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2002.10903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muller M, Trocme C, Lardy B, Morel F, Halimi S, Benhamou PY. Matrix metalloproteinases and diabetic foot ulcers: The ratio of MMP-1 to TIMP-1 is a predictor of wound healing. Diabet Med. 2008;25:419–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Min D, Bolton T, Nubé V, Twigg SM, Yue DK, et al. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 predicts poor wound healing in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:117–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thönes S, Rother S, Wippold T, Blaszkiewicz J, Balamurugan K, Moeller S, et al. Hyaluronan/collagen hydrogels containing sulfated hyaluronan improve wound healing by sustained release of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor. Acta Biomater. 2019;86:135–47. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim D, Kim SY, Mun SK, Rhee S, Kim BJ. Epidermal growth factor improves the migration and contractility of aged fibroblasts cultured on 3D collagen matrices. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35:1017–25. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu Z, Tang Y, Fang H, Su Z, Xu B, Lin Y, et al. Decellularized scaffolds containing hyaluronic acid and EGF for promoting the recovery of skin wounds. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2015;26:5322. doi: 10.1007/s10856-014-5322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su Z, Ma H, Wu Z, Zeng H, Li Z, Wang Y, et al. Enhancement of skin wound healing with decellularized scaffolds loaded with hyaluronic acid and epidermal growth factor. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2014;44:440–8. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]