Abstract

We explored the role of the transcription factor, NF-κB, and its upstream kinase IKKβ in regulation of migration, invasion, and metastasis of cisplatin-resistant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). We showed that cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells have a stronger ability to migrate and invade, as well as display higher IKKβ/NF-κB activity compared to their parental partners. Importantly, we found that knockdown of IKKβ, but not NF-κB, dramatically impaired cell migration and invasion in these cells. Consistent with this, the IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA, also inhibited cell migration and invasion. Previous studies have already shown that N-Cadherin, an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) marker, and IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, play important roles in regulation of HNSCC migration, invasion, and metastasis. We found that cisplatin-resistant HNSCC expressed higher levels of N-Cadherin and IL-6, which were significantly inhibited by CmpdA. More importantly, we showed that CmpdA treatment dramatically abated cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cell metastasis to lungs in a mouse model. Our data demonstrated the crucial role of IKKβ in control of migration, invasion, and metastasis, and implicated that targeting IKKβ may be a potential therapy for cisplatin-resistant metastatic HNSCC.

Keywords: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, HNSCC, IKKβ, NF-κB, IKKβ inhibitor, migration, invasion, metastasis, cisplatin resistance

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) are currently the sixth most common cancer worldwide [1, 2]. The major factors that affect overall patient survival are due to recurrence and metastasis of cancer following standard therapies such as surgery, radiation therapy, or a combination [3–5]. Currently, cisplatin-based chemotherapy remains the primary option for patients with recurrent and metastatic HNSCC, but nearly all patients will eventually become resistant to cisplatin treatment and die within a year. Therefore, it is important to define the key signaling pathways that regulate HNSCC metastasis and discover effective inhibitors to target them and overcome metastasis [3, 6–8]. In addition, a major determinant for cancer cell metastasis is its ability to migrate and invade. Therefore, identification of the crucial proteins and signaling pathways that associate with cancer cell migration and invasion remains vital to discovery of new therapies for HNSCC metastatic cancer [8].

Multiple survival pathways involve HNSCC development, progression, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance [4, 9–11]. Many studies have demonstrated that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) plays an important role in HNSCC, since more than 90% of head and neck cancers overexpress EGFR [4, 10, 12]. EGFR overexpression correlates with poorer outcomes in HNSCC patients because it leads to the activation of several crucial pathways including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mTOR, MEK/MAPK/ERK, protein kinase C (PKC), JAK/STAT, and IKK/NF-κB pathways [9–11, 13–15]. These signaling pathways control gene expression, cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion, as well as metastasis through different mechanisms [11, 12].

The transcription factor NF-κB plays many roles in different types of cancer, including head and neck cancer. It has been shown that NF-κB is activated in different stages of HNSCC. NF-κB cross-talk with multiple signaling pathways downstream of EGFR promotes cancer cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis, as well as accelerates metastasis through transcription of its target gene. NF-κB activity is modulated by its upstream kinases IKKα and IKKβ, which cooperate to regulate proliferation and migration in HNSCC, though the mechanisms remain unclear [11, 13–16]. In this study, we explored the role of IKKβ and NF-κB in regulation of migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant HNSCC. We showed that IKKβ controls cell migration and invasion independent of NF-κB, and CmpdA, an IKKβ inhibitor, inhibits cell migration and invasion, as well as metastasis of cisplatin-resistant HNSCC.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Cal 27 cells were obtained from ATCC and the UMSCC74B cell lines were purchased from Dr. Thomas E. Carey (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). All cell lines were authenticated by Short Tandem Repeat (STR) assay and tested for mycoplasma contamination in the Genomics and Translational Core Facility of the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center (UMGCCC). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, and 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco).

Antibodies and reagents

The antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology: phospho-IKKα (S176)/β (S177) (CST-2697 and CST-2078), IKKα (CST-2682), IKKβ (CST-8943), phospho-p65-S536 (CST-3033), p65 (CST-6956), phospho-STST3-Y705 (CST-9113), STST3 (CST-4904), E-Cadherin (CST-3195), N-Cadherin (CST-4061), β-actin (CST-4967) and GAPDH (CST-5174). Protease and phosphatase inhibitors were from Roche. The IKKβ inhibitor CmpdA (Bay65–1942) was provided by Dr. Albert Baldwin at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill [17].

Cell lysis and Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in ice-cold M-PER lysis buffer purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (78501). Cell lysates were spun down by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 15,000 × g at 4 °C and protein concentration was measured with the BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 20–50 μg of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was transferred to a PVDF membrane, blocked in 5% nonfat milk, and blotted with the indicated antibodies.

siRNA transfection

siRNA SMARTpool IKKβ (catalog #M-003503) and NF-кB (p65) (catalog #M-003533) were from Dharmacon. Each siRNA represents four pooled SMART-selected siRNA duplexes that target the indicated mRNA. Cells were transfected with indicated SMARTpool siRNA or nonspecific control pool using (D-001810) Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX™ Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were recovered in full serum. Cells were harvested 48–72 hours post-siRNA transfection.

Colony focus assay

Cells (1000/well) transfected with siRNA control, IKKβ, or NF-кB for 24 hours were seeded in 12-well plates and grown in normal media for 10 days, washed once with 1x PBS, fixed with methanol, and stained with crystal violet.

Measurement of cell migration and invasion

xCELLigence real-time migration and invasion experiments were conducted as described previously [18].

Generation of luciferase-Yellow fluorescent protein expressing cells

CL20IM-luc-IYFP lentiviral supernatant (yellow fluorescent protein, YFP, and luciferase controlled by the same promotor) was the generous gift of the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Vector Core. Cal27 cells were harvested and plated into a 24 well plate, and the following day lentiviral supernatant was added to the cells. After 72 hours, cells were harvested and re-plated for expansion. YFP-luciferase positive cells were sorted on the Aria II platform (BD Biosciences) in UMGCCC’s flow cytometry core. YFP-luciferase positive cells were then expanded, frozen viably and re-tested by STR analysis for cell line authentication prior to in vivo studies.

Tumor metastasis in lungs in mice

Six-week old female NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) or NRG (NOD.Cg-Rag1tm1Mom Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) mice were obtained from and bred by University of Maryland Baltimore’s Comparative Medicine Department under a license from Jackson Labs (Maine). All in vivo experiments were carried out in compliance with institutional and NIH guidelines and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations for care and use of experimental animals. In the metastasis model, 1×106 YFP/luc-Cal 27cells were injected intravenously into 6-week old, female NRG or NSG mice. Within hours of the IV injection, mice were imaged for bioluminescence on Perkin Elmer’s IVIS Xenogen system following intraperitoneal injection with 150 mg/kg luciferin. At the termination of the experiment, mice were euthanized and lungs excised and imaged for YFP.

Statistics

In vitro experiments were expressed as mean ± SD using 3 independent experiments. Comparisons between groups were carried out by 2-way ANOVA or Student’s t-test. For mouse studies, the two-tailed t test was used to compare tumor numbers between control and treatment groups. P values ˂ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells show elevated IKKβ/NF-κB signaling and have stronger abilities to migrate and invade

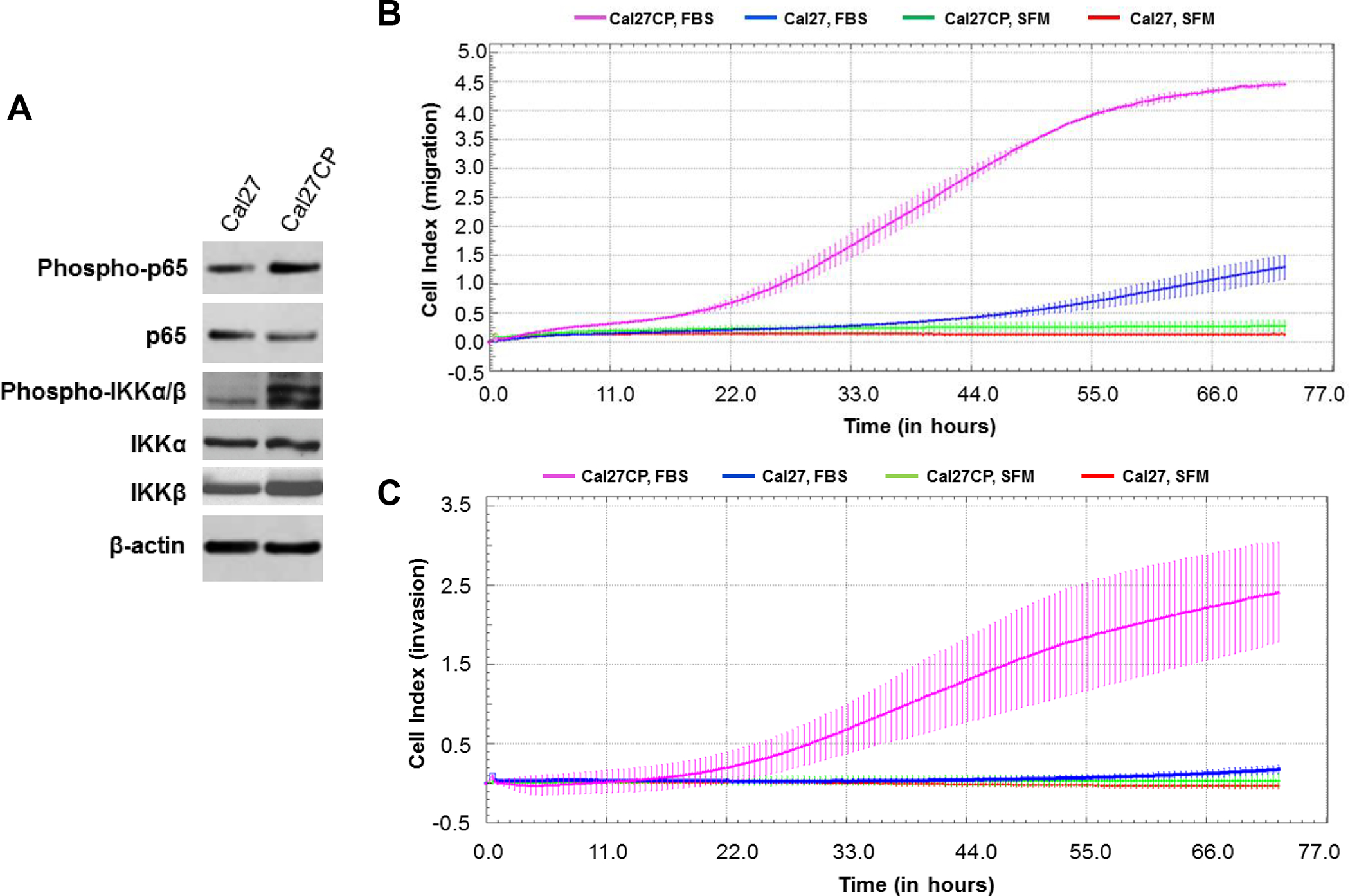

CAL 27 is a frequently used oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line for HNSCC studies, including those that involve cisplatin resistance [19]. We recently established a cisplatin-resistant Cal27CP cell line by treatment of parental Cal27 cells with 0.5 μM to 5 μM of cisplatin for 6 months. The IC50 of Cal27 and Cal27CP to cisplatin were 3 μM and 15 μM, respectively. In the Western blot analysis, increased levels of IKKα/β phosphorylation, especially IKKβ, were detected in Cal27CP cells. Consistently, phosphorylation of NF-κB (p65), the downstream target of IKK, was higher in Cal27CP cells than in parental cells (Figure 1A). These results indicated that IKK/NF-κB signaling was up-regulated in cisplatin-resistant Cal27 (Cal27CP) cells. Next, the xCELLigence real-time cell system was used to monitor the migration ability of Cal27 and Cal27CP cells. Cal27CP cells showed an increase in migration over time (Figure 1B). In addition, Cal27CP cells had a stronger ability to invade compared to their parental partners (Figure 1C). These data are consistent with the previous report that the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) increased in cisplatin-resistant Cal27CP cells [19].

Figure 1. Cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells have elevated IKKβ/NF-κB signaling and stronger abilities to migrate and invade.

A: Cal27 and Cal27CP cells were lysed and the phosphorylation status and total protein levels of IKKα/β and p65, as well as β-actin, were analyzed by Western blot. B and C: Cal27 and Cal27CP cell migration (B) and invasion (C) were monitored by xCELLigence system. SFM: serum-free medium.

Knockdown of IKKβ, but not NF-κB, impairs migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant HNSCC

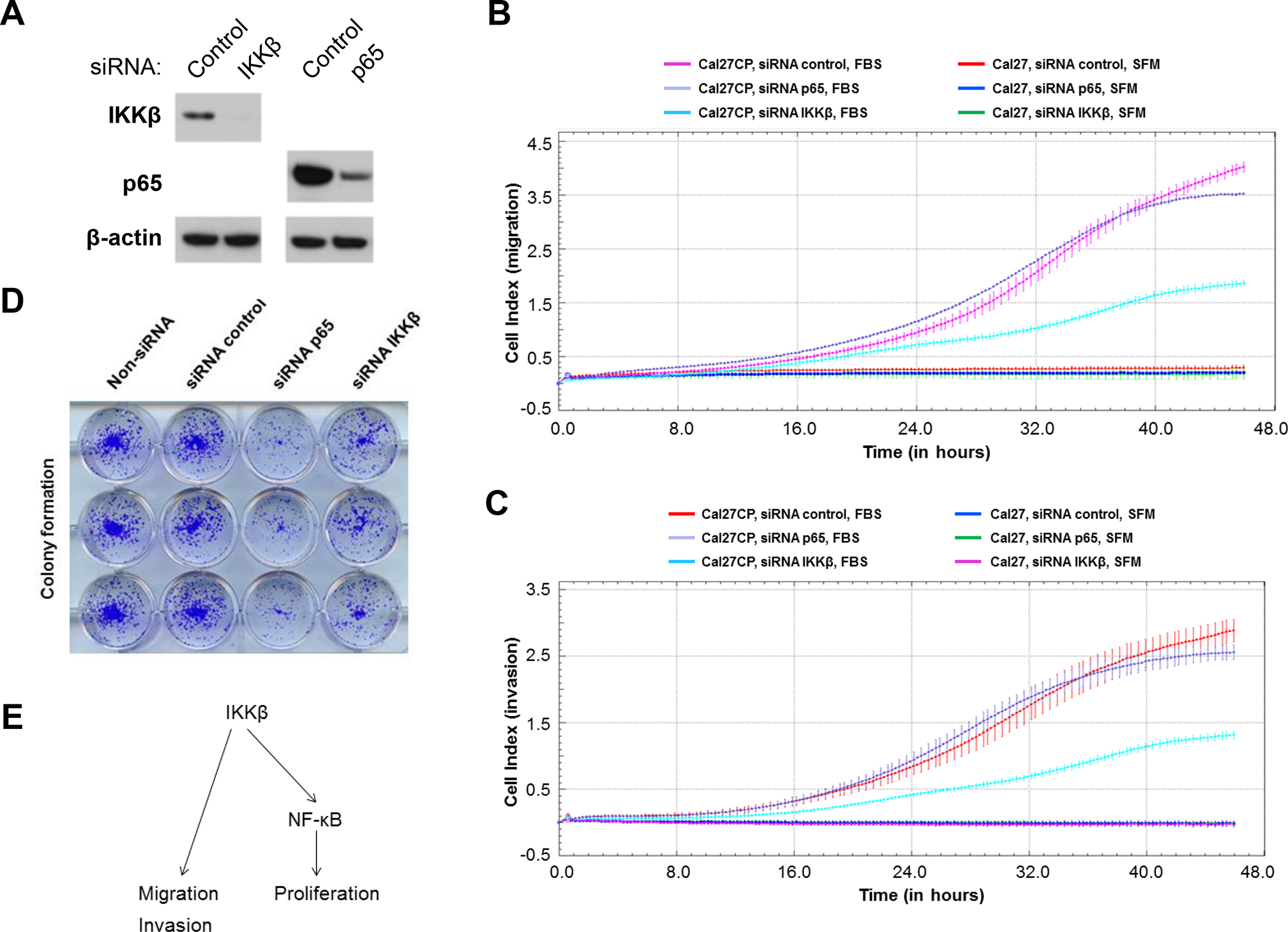

Next, we determined the roles of IKKβ and NF-κB in the regulation of Cal27CP cell migration and invasion. siRNA against IKKβ and NF-κB (p65) was used to knock down IKKβ and NF-κB, respectively, in Cal27CP cells. Western blot analysis showed that IKKβ and NF-κB were effectively knocked down 48 hours post-transfection (Figure 2A). In a parallel experiment, cell migration and invasion were monitored after knockdown of either IKKβ or NF-κB. Knockdown of IKKβ, but not NF-κB, dramatically impaired cell migration (Figure 2B) and significantly decreased cell invasion (Figure 2C). It should be noted that we observed significant difference in cell proliferation between cells treated with control siRNA and IKKβ siRNA in 96 hours (Supplementary Figures 1B), rather than 48 hours (Supplementary Figures 1A). Thus, depletion of IKKβ-induced inhibition of cell migration and invasion did not occur through inhibition of cell proliferation. Interestingly, colony assay experiments showed that NF-κB knockdown more significantly decreased cell proliferation compared to IKKβ knockdown (Figure 2D). Our data indicate that IKKβ regulates cell migration and invasion independent of NF-κB, whereas it may regulate cell proliferation through NF-κB (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. IKKβ knockdown impairs cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cell migration and invasion.

A: Cal27CP cells were transfected with non-target siRNA, siRNA IKKβ, or siRNA p65 for 48 hours and the expression of IKKβ, p65 and β-Actin was tested by Western blot. B and C: Cal27CP cells were transfected with non-target siRNA, siRNA IKKβ, or siRNA p65 for 48 hours and cell migration (B) and invasion (C) were monitored by xCELLigence system. SFM: serum-free medium. D: Cal27CP cells transfected with non-target siRNA, siRNA IKKβ, or siRNA p65 for 24 hours were seeded in 12 well plates (800/well) and colony formation was observed after 10 days. E: IKKβ regulates cell migration and invasion independent of NF-κB, whereas it may regulate cell proliferation through NF-κB migration in Cal27CP cells.

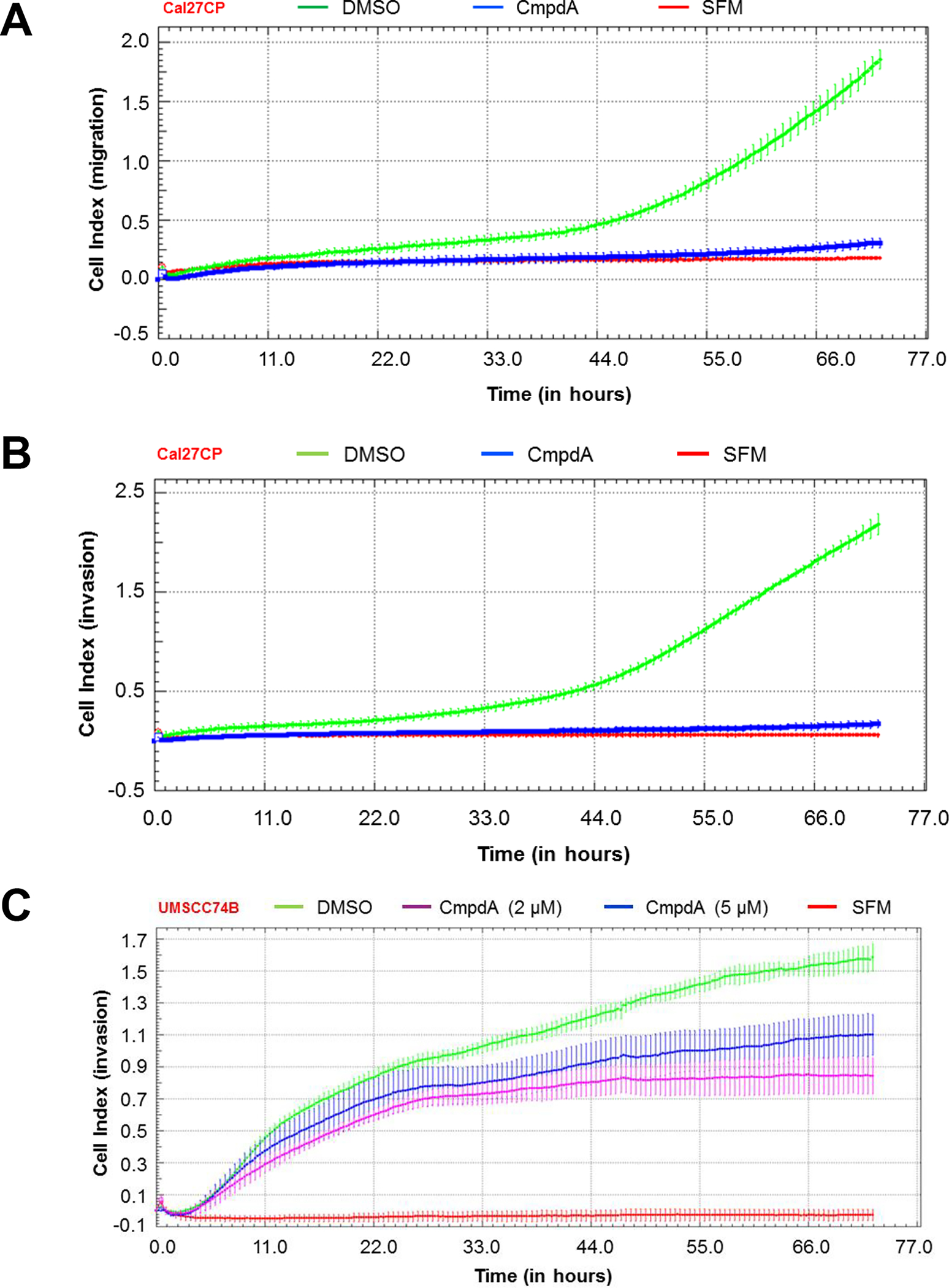

IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA, inhibits EMT and cell migration and invasion

CmpdA is a selective IKKβ inhibitor [17, 18, 20]. To test whether IKKβ/NF-κB inhibition suppresses migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant HNSCC, Cal27CP cells were treated with CmpdA (2 μM), and we subsequently monitored cell migration and invasion. CmpdA treatment significantly inhibited cell migration (Figure 3A) and invasion (Figure 3B). The UMSCC74B cell line was derived from a patient treated with chemotherapy [21]. Our data demonstrated that these cells were resistant to cisplatin with an IC50 of 20 μM. The xCELLigence real-time cell system also demonstrated that CmpdA dramatically inhibited UMSCC74B cell invasion (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA, inhibits cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cell migration and invasion.

A and B: Cal27CP cells were treated with IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA (2 μM) and cell migration (A) and invasion (B) were monitored. C: UMSCC74B cells were treated with increasing doses of CmpdA and cell invasion was monitored.

In a separate experiment, we treated Cal27CP cells with 2 or 5 μM of CmpdA for 48 hours and found that there was no significant inhibition of cell proliferation (Supplementary Figures 2). These results indicated that CmpdA inhibition of cell migration and invasion is independent of inhibition of cell proliferation. However, treatment of Cal27CP Cells with 1 μM of CmpdA significantly decreased colony formation in 10 days (Supplementary Figures 3). These data are consistent with the results shown in Figure 2, which demonstrates that IKKβ depletion decreased cell proliferation over a longer period of time. Thus, IKKβ plays roles in regulation of cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Our data demonstrate that IKKβ targeting may inhibit EMT in cisplatin-resistant HNSCC.

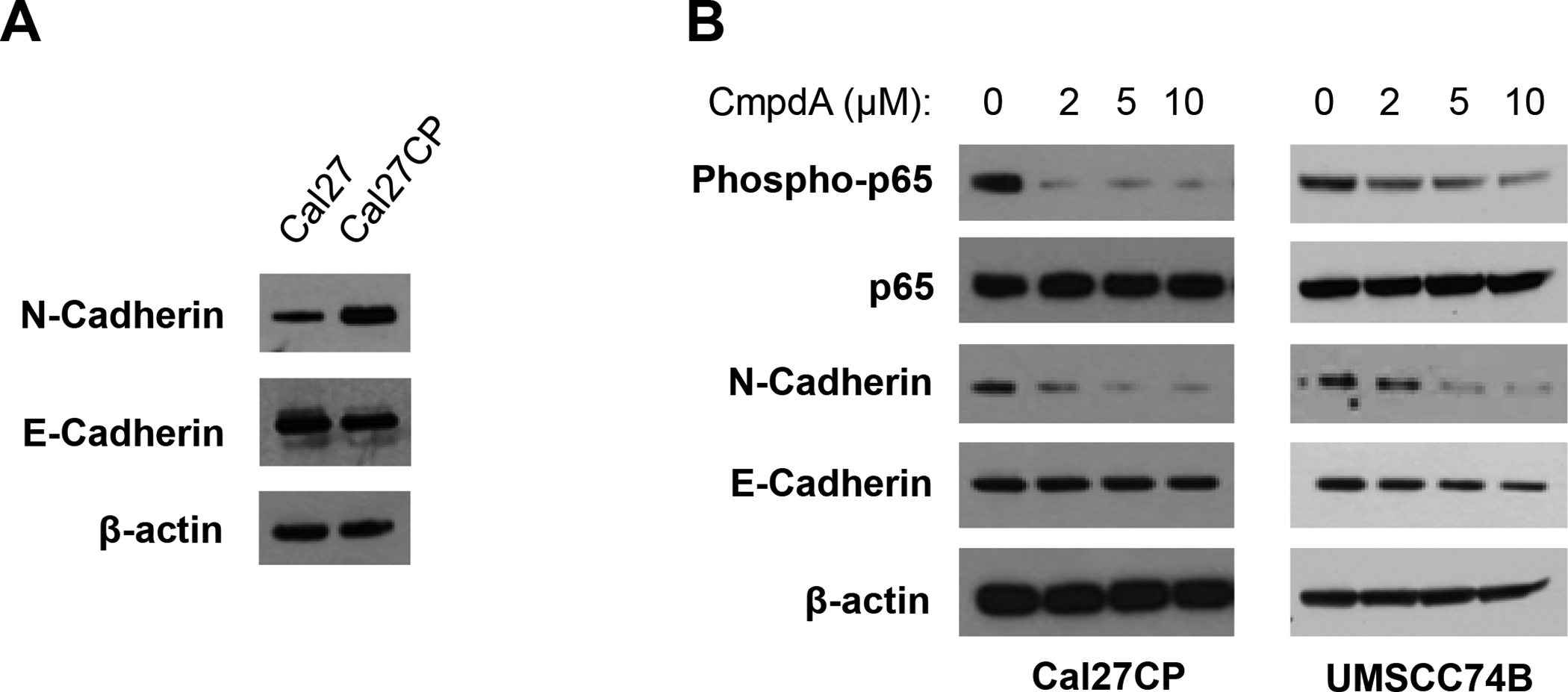

IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA, inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) marker, N-cadherin, expression in cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells

EMT plays a crucial role in regulation of cancer cell migration and invasion. N-cadherin and E-cadherin are important biomarkers for EMT [8]. Sun, et. al., previously reported that cisplatin-resistant Cal27 cells showed higher levels of N-cadherin, but lower levels of E-cadherin in comparison to the parental cells [19]. A similar result was found in our Cal27CP cells compared to Cal27 cells (Figure 4A). Next, we treated Cal27CP and UMSCC74B cells with CmpdA for 72 hours to test its effects on the expression of N- and E-cadherin expression. The phosphorylation of p65, an IKKβ substrate, significantly decreased in response to CmpdA treatment, which suggested that CmpdA treatment inhibited IKKβ/NF-κB signaling (Figure 4A). Importantly, the expression of N-cadherin was also downregulated by CmpdA treatment, while there were no changes to E-cadherin levels (Figure 4B). These data demonstrate that CmpdA inhibition of migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant HNSCC may involve N-Cadherin inhibition.

Figure 4. CmpdA inhibits N-Cadherin expression in cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells.

A: Cal27 and Cal27CP cells were lysed and the expression of E-Cadherin, N-Cadherin, and β-actin was detected by Western blot. B: Cal27CP and UMSCC74B cells were treated with increasing doses of CmpdA for 24 hours and the levels of phosphor-p65, p65, E-Cadherin, N-Cadherin, and β-actin were detected by Western blot.

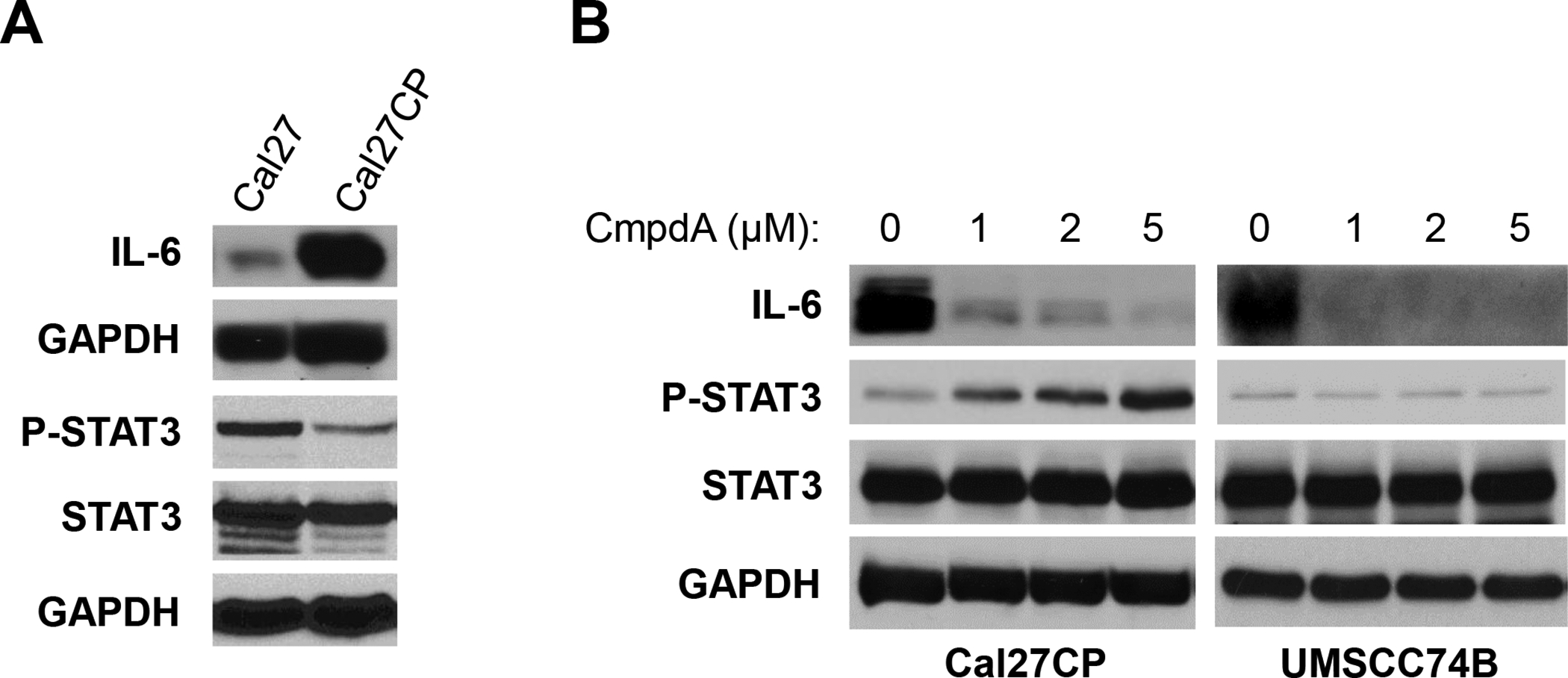

IL-6 expression in cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells is significantly elevated and is also inhibited by CmpdA

Previous reports demonstrated that IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, played a crucial role in regulation of migration, invasion, and metastasis through the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway in HNSCC [22–27]. Here, we found that IL-6 expression in Cal27CP cells was much higher than that in Cal27 cells, whereas the phosphorylation of STAT3 in Cal27CP cells was lower (Figure 5A). Furthermore, we showed that CmpdA treatment dramatically decreased IL-6 expression and led to increased STAT3 phosphorylation in Cal27CP but not UMSCC74B cells (Figure 5B). These results suggest that CmpdA can inhibit migration and invasion through IL-6, independent of STAT3.

Figure 5. CmpdA inhibits IL-6 expression in cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells.

A: Cal27 and Cal27CP cells were lysed and the levels of IL-6, phospho-STAT3, Stat3, and GAPDH were detected by Western blot. B: Cal27CP and UMSCC74B cells were treated with increasing concentrations of CmpdA for 24 hours and the levels of IL-6, phospho-STAT3, Stat3, and GAPDH were detected by Western blot.

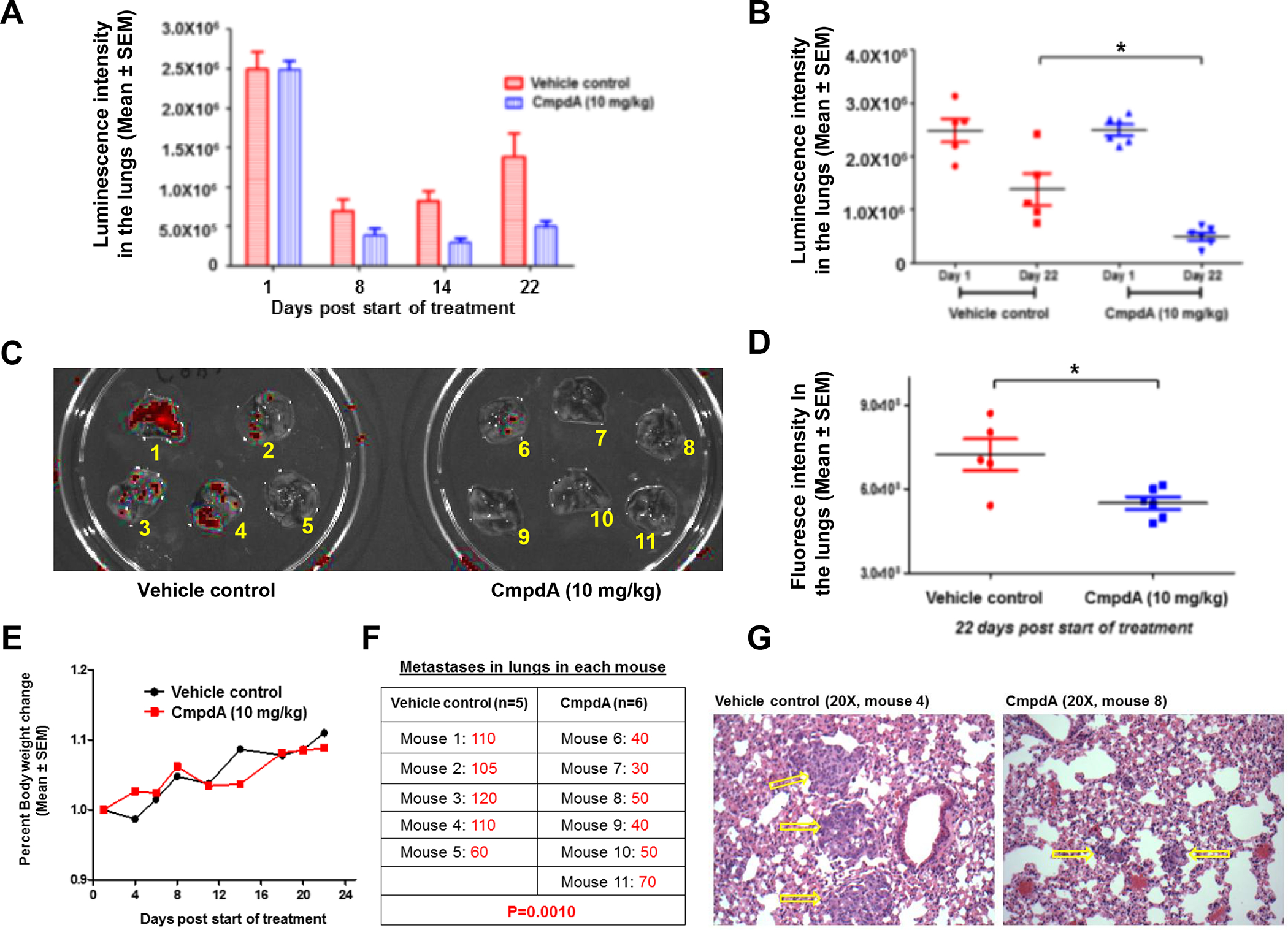

CmpdA abates Cal27CP cell metastasis to lungs in mice

To better monitor tumor metastasis in vivo, we transduced Cal27 and Cal27CP cells with a lentivirus that expressed yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) and luciferase (luc) in order to visualize these cells in mice and in tissue. YFP expression was confirmed under fluorescence microscopy in both Cal27 (YFP/luc-Cal27) and Cal27CP (YFP/luc-Cal27CP) cells (Supplementary Figure 4A). Proliferation assays showed that the IC50 of YFP/luc-Cal27CP cells was 15 μM, whereas that in YFP/luc-Cal27 cells was around 4 μM. Thus, the IC50 of YFP/luc-Cal27CP cells remains consistent with prior studies (Supplementary Figure 4B). YFP/luc-Cal27CP cells were intravenously injected into mice and luminescence was measured. Significant luminescence signaling, which correlates to disease burden, gradually increased from days 4 to 36 (Supplementary Figures 4C and 4D). These results demonstrate that YFP/luc-Cal27CP cells metastasize to the lungs, making this a good model to study cisplatin-resistant, metastatic HNSCC.

Next, we determined whether CmpdA could suppress metastatic cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cell growth in lungs. YFP/luc-Cal27CP cells treated with vehicle control or CmpdA (2.5 μM) for 48 hours were injected into NSG mice and eleven mice with similar levels of luminescence signaling in their lungs were divided into two groups: Group 1 (vehicle control) contained five mice, whereas Group 2 (CmpdA treatment) had six. The mice were treated with vehicle control or 10 mg/kg CmpdA starting from day 3 for three weeks (twice/week) and luminescence signaling in lungs was monitored at days 1, 8, 14, and 22 (Figure 6A). There were no significant differences in photo intensity of luminescence between treatment and control groups after 24 hours (Figure 6A). However, the bioluminescence intensity in the treatment group was weaker than the control group mice on days 8 and 14, and that was further confirmed on day 22 (Figures 6A and B). Furthermore, when the mice were sacrificed, lungs removed, and luciferase activity measured, a significant decrease in luciferase signaling was found in the CmpdA-treated group (Figures 6C and D). In addition, there was no difference in mice body weight between the treatment and control groups (Figure 6E). Furthermore, we found that metastatic lesions (numbers) in the mice treated with CmpdA were significantly less than those in the mice treated with vehicle control (Figure 6F), which suggested that CmpdA treatment could decrease tumor numbers (Figure 6F). Furthermore, we found that metastatic lesions (sizes) in the mice treated with CmpdA were significantly smaller than those in the mice treated with vehicle control (Figure 6G). In summary, CmpdA inhibits growth of metastatic cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells through inhibition of both metastasis and colony formation.

Figure 6. CmpdA abates Cal27CP cell metastasis to lungs in mice.

A: 1×106 YFP/luc-Cal27CP cells pre-treated for 72 hours with vehicle control or 2.5 μM CmpdA were injected intravenously into NRG mice. On day of injection, mice were imaged and grouped into the control group (Group 1; n=5) and the treatment group (Group 2; n=6) so that mean intensity of luminescence signaling in lungs was similar. Mice were then treated intraperitoneally (IP) three times per week with 10% DMSO (Group 1) or 10 mg/kg CmpdA (Group 2), for three weeks. Luminescence signaling (photon intensity) in lungs was monitored. B: Intensity of luminescence signaling in lungs at days 1 (start) and 22 (end) were compared (*P˂0.05). C: 11 mice labeled from 1 to 11 (control group: 1–5; and treatment group: 6–11) were euthanized at day 22, lungs were washed and collected, and fluorescence images (red) were taken. D: Fluorescence images on lungs were measured (**P˂0.01). E: Percent body weight changes in mice treated with vehicle control or CmpdA were recorded from days 1 to 22. F: Lung lesions in mice treated with vehicle control or CmpdA (mice 1–11 in Figure D) were counted and compared. G: Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of paraffin sections of lungs from control and CmpdA treated mice are shown at the same magnification. Yellow arrows indicate metastatic lung tumors.

Discussion

In this study, we established a cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cell line derived from oral squamous cell carcinoma Cal27 cells and found that IKKβ/NF-κB signaling was upregulated in these cells. Consistent with previous reports [19], we showed that Cal27CP cells have a stronger ability to migrate and invade compared to the parental Cal27 cells. Importantly, we found that knockdown of IKKβ dramatically slowed cell migration and invasion in Cal27CP cells. Furthermore, the IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA, decreased N-cadherin expression and inhibited cell migration and invasion in Cal27CP cells, as well as in UMSCC7B cells, a patient-derived, chemotherapy-resistant HNSCC cells. CmpdA also decreased Cal27CP cell metastasis and invasion in the lungs of mice. Our data demonstrated the crucial role that IKKβ plays to control cell invasion and metastasis in cisplatin-resistant HNSCC and indicated that use of IKKβ as a target could be a potential strategy to treat cisplatin-resistant, metastatic HNSCC.

Many studies, including ours, have already shown that NF-κB plays important roles in cell proliferation, chemotherapy resistance, migration, invasion, and metastasis in many cancer types, including HNSCC [16, 28–30]. The study by Wu, et. al., demonstrated that NF-κB regulated breast cancer metastasis through transcriptional regulation of Snail [31]. Li, et. al., showed that NF-κB regulated Twist to control cancer invasion and metastasis [32]. We previously reported that NF-κB promoted prostate cancer proliferation, migration, and invasion, and that the IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA, inhibited these processes through NF-κB inhibition [18]. In the current study, we found that IKKβ regulated cell migration and invasion, independent of NF-κB. It should be noted that this regulation may be cell-type specific.

The most common biochemical change associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is the over-expression of N-cadherin and the decrease of E-cadherin expression. N-cadherin and E-cadherin are transcriptionally regulated by multiple proteins such as Snail (SNAI1), Slug (SNAI2), and ZEB-1 [33]. Down-regulation of N-cadherin and increases of E-cadherin expression leads to inhibition of migration and invasion [33]. Interestingly, the IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA, inhibited only the expression of N-cadherin without any effects on E-cadherin. We are currently attempting to ascertain the precise mechanism(s) by which IKKβ regulates N-cadherin.

While many studies have already demonstrated that NF-κB controls IL-6/STAT3 signaling to promote EMT and tumor metastasis [22–27], we have shown that the IKKβ inhibitor CmpdA inhibits NF-κB and IL-6, while still causing elevated STAT3 phosphorylation. It will be interesting to elucidate the detailed molecular links among IKKβ/NF-κB, IL-6, and STAT3 in more cisplatin-resistant HNSCC models.

In our study, CmpdA targeting of IKKβ caused dramatic inhibition of migration and invasion in vitro and significant inhibition of metastasis in vivo. These data suggest that the inhibition of IKKβ alone, or in combination with other targeted therapies, could be a potential regimen for treatment of cisplatin-resistant, metastatic HNSCC. We are currently investigating new potential crucial pathways associated with IKK/NF-κB activation in order to identify the most effective multiple-targeted therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Translational Core Facility of the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Cancer Center for analyzing cell migration and invasion through xCELLigence real-time cell system and in vivo treatment study. We also thank Dr. Albert S. Baldwin at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for providing the IKKβ inhibitor, CmpdA (Bay65-1942).

Grant Support

This research was supported, in part, by the grants from the NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI) to H.D. (R00CA149178 and R01CA212094), and the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center. The funding agency was not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- HNSCC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- IKKβ

inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-B

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, and Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin, 2019. 69(1): p. 7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, et al. , Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018. 68(6): p. 394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pendleton KP and Grandis JR, Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy Options for Recurrent and/or Metastatic Squamous Cell Cancer of the Head and Neck. Clin Med Insights Ther, 2013. 2013(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ, and Brakenhoff RH, The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 2011. 11(1): p. 9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH, and Leemans CR, Treatment choice for locally advanced head and neck cancers on the basis of risk factors: biological risk factors. Ann Oncol, 2012. 23 Suppl 10: p. x173–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas SM and Grandis JR, The current state of head and neck cancer gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther, 2009. 20(12): p. 1565–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Specenier PM and Vermorken JB, Current concepts for the management of head and neck cancer: chemotherapy. Oral Oncol, 2009. 45(4–5): p. 409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith A, Teknos TN, and Pan Q, Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol, 2013. 49(4): p. 287–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molinolo AA, et al. , Dysregulated molecular networks in head and neck carcinogenesis. Oral Oncol, 2009. 45(4–5): p. 324–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalyankrishna S and Grandis JR, Epidermal growth factor receptor biology in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2006. 24(17): p. 2666–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Psyrri A, Seiwert TY, and Jimeno A, Molecular pathways in head and neck cancer: EGFR, PI3K, and more. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 2013: p. 246–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabinowits G and Haddad RI, Overcoming resistance to EGFR inhibitor in head and neck cancer: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol, 2012. 48(11): p. 1085–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shostak K and Chariot A, EGFR and NF-kappaB: partners in cancer. Trends Mol Med, 2015. 21(6): p. 385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown M, et al. , NF-kappaB in carcinoma therapy and prevention. Expert Opin Ther Targets, 2008. 12(9): p. 1109–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang F, et al. , Current and potential inflammation targeted therapies in head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2009. 9(4): p. 389–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nottingham LK, et al. , Aberrant IKKalpha and IKKbeta cooperatively activate NF-kappaB and induce EGFR/AP1 signaling to promote survival and migration of head and neck cancer. Oncogene, 2014. 33(9): p. 1135–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziegelbauer K, et al. , A selective novel low-molecular-weight inhibitor of IkappaB kinase-beta (IKK-beta) prevents pulmonary inflammation and shows broad anti-inflammatory activity. Br J Pharmacol, 2005. 145(2): p. 178–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, et al. , Targeting IkappaB Kinase beta/NF-kappaB Signaling in Human Prostate Cancer by a Novel IkappaB Kinase beta Inhibitor CmpdA. Mol Cancer Ther, 2016. 15(7): p. 1504–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun L, et al. , MiR-200b and miR-15b regulate chemotherapy-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human tongue cancer cells by targeting BMI1. Oncogene, 2012. 31(4): p. 432–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, et al. , A positive feedback loop involving EGFR/Akt/mTORC1 and IKK/NF-kB regulates head and neck squamous cell carcinoma proliferation. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(22): p. 31892–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenner JC, et al. , Genotyping of 73 UM-SCC head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Head Neck, 2010. 32(4): p. 417–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA, and Grandis JR, Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2018. 15: p. 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith CW, et al. , The host environment promotes the development of primary and metastatic squamous cell carcinomas that constitutively express proinflammatory cytokines IL-1alpha, IL-6, GM-CSF, and KC. Clin Exp Metastasis, 1998. 16(7): p. 655–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choudhary MM, et al. , Interleukin-6 role in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma progression. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2016. 2(2): p. 90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun W, et al. , Interleukin-6 promotes the migration and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines and upregulates the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9. Int J Oncol, 2014. 44(5): p. 1551–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen MF, et al. , IL-6 expression predicts treatment response and outcome in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Mol Cancer, 2013. 12: p. 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanazawa T, et al. , Interleukin-6 directly influences proliferation and invasion potential of head and neck cancer cells. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 2007. 264(7): p. 815–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, et al. , IKK phosphorylation of NF-kappaB at serine 536 contributes to acquired cisplatin resistance in head and neck squamous cell cancer. Am J Cancer Res, 2015. 5(10): p. 3098–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vander Broek R, et al. , Chemoprevention of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma through inhibition of NF-kappaB signaling. Oral Oncol, 2014. 50(10): p. 930–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Waes C, Targeting NF-kappaB in mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov, 2011. 1(3): p. 200–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y, et al. , Stabilization of snail by NF-kappaB is required for inflammation-induced cell migration and invasion. Cancer Cell, 2009. 15(5): p. 416–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li CW, et al. , Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by TNF-alpha requires NF-kappaB-mediated transcriptional upregulation of Twist1. Cancer Res, 2012. 72(5): p. 1290–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peinado H, Portillo F, and Cano A, Transcriptional regulation of cadherins during development and carcinogenesis. Int J Dev Biol, 2004. 48(5–6): p. 365–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.