Abstract

Critical cases of COVID-19 require respiratory support provided primarily by mechanical ventilators. But, as per the current trend, about 15% of the cases require hospitalization and less than 5% cases are critical. Due to the massive number of COVID-19 cases all over the world, the ventilator requirement is increasing, and these traditional ventilators are quite expensive and are occupied for the critical cases, thus available in limited numbers. In this regard, BiPAP (Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure) ventilation support can be used for the less critical cases where patients do not require intubation by specialized staff and also minimizing the risk of infection during the procedure. The current article aims to deliver a design of an inexpensive BiPAP with an infection-free exhaust. BiPAP is a mode of ventilation which maintains positive pressure for air intake, and a low or zero pressure is created for expiration. The BiPAP suggested in the current article uses an air blower connected to an Arduino via a speed controller, the level of pressure and breathing rate are programmed in the Arduino, thus, the blower functions in BiPAP mode. The 3D printed mask proposed here comprises of a unique design for the intake and exhalation of air; and comprises of two sizes to fit all adults while avoiding any leakage. The design suggested is further tweaked for emergency use to support up to four patients using a single BiPAP. The mass production of the same would cost approx. INR 6500 or 85 USD.

Keywords: BiPAP, Multi-patient, Respiratory support, Universal size, Non-invasive ventilation

Introduction

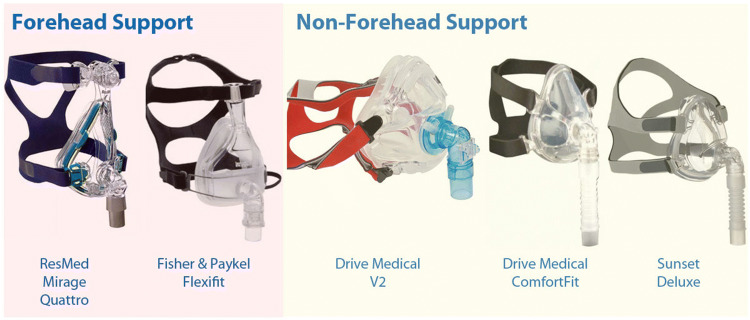

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented an unprecedented challenge to the healthcare services around the world. The latest available WHO data suggests that around 0.7 hospital beds are available per 1000 people in India (The World Bank 2020), this number is lower than what is recommended by the WHO. COVID-19 is extremely contagious and the mortalities are growing at an alarming rate (The Lancet 2020). Thus, healthcare facilities should be suitably equipped to incorporate the sudden rise of patients. As per the recent studies, about 15% of the COVID-19 patients require hospitalization, and less than 5% of the patients need intensive care and respiratory support through ventilators which are available in limited numbers (CDC 2020). The conventional mechanical ventilation is an invasive technique and should be reserved for highly critical cases. Prolonged ventilator support causes lung injury and its invasive nature impends infection (Arca et al. 2015). Alternative non-invasive respiratory support including BiPAP machines reduces the need for ventilation (Shaffer et al. 2012). A BiPAP machine though generally used to cure sleep apnea, can be used for less critical cases which do not require ventilators, and for the critical cases waiting for ventilator support (Poponick et al. 1997). Hence, alternative respiratory support systems reduce the required number of ventilators. A BiPAP machine is much easier to operate and inexpensive as compared to ventilators. Commercial BiPAPs are expensive and the masks included leak the exhaled breath to the surroundings, which increases the risk of infection to healthcare workers. The various types of commercial non-invasive masks are shown in Fig. 1. As evident from Fig. 1, all of the variants of commercial non-invasive masks contain a port for the inlet but do not have a separate port for the outlet. Hence, there is no provision for filtration of the exhaled air.

Fig. 1.

Commercial non-invasive masks (Vitality Medical 2020)

A BiPAP referred henceforth in the current article is the proposed BiPAP machine unless stated otherwise. The current article proposes an affordable, compact and infection-free BiPAP machine which includes a universal size mask with a HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filter. A HEPA filter blocks COVID-19 causing particulates, which was established during the 2003 SARS outbreak (Kim et al. 2008). Commercial non-invasive ventilation machines do not have a mask that filters out the exhaled air (Castro-Codesal et al. 2019; Wilke and Ghamande 2013). Commercial BiPAP mechanism is very complex, and the proposed design is minimal, easy to operate, made out of readily available and economical electronic/mechanical parts. It has been established that a single ventilator can support multiple patients, provided that airflow is sufficient (Neyman and Irvin 2006). The FDA approved the use of splitters to support four patients on a single ventilator during emergencies (ECRI 2020). Therefore, the application of splitters can help the medical department to reduce the resources and time required to curb the imminent shortage of ventilators. Various hospitals in the US have used the splitters in case of ventilator shortage (Baskauf and Nalpathanchil 2020). The use of splitters in BiPAPs for non-critical is safer as compared to the traditional ventilators owing to their low pressure requirement and limited complexity of electronic parts as compared to the ventilators. The final design is envisioned to support four patients using a single BiPAP. The BiPAP is intended to be set up in hospitals to treat non-critical COVID-19 cases and as backup respiratory support for critical cases until a conventional mechanical ventilator is available. The simple working of the BiPAP empowers remote hospitals with respiratory support which do not have trained anesthetists.

Device Design and Working

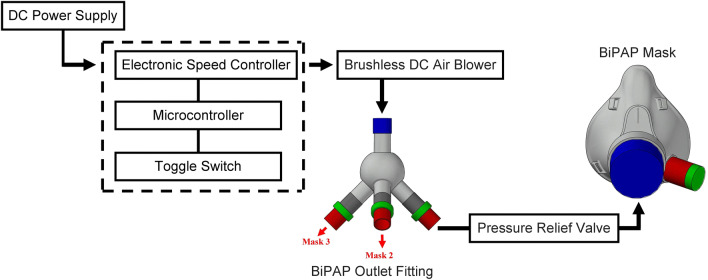

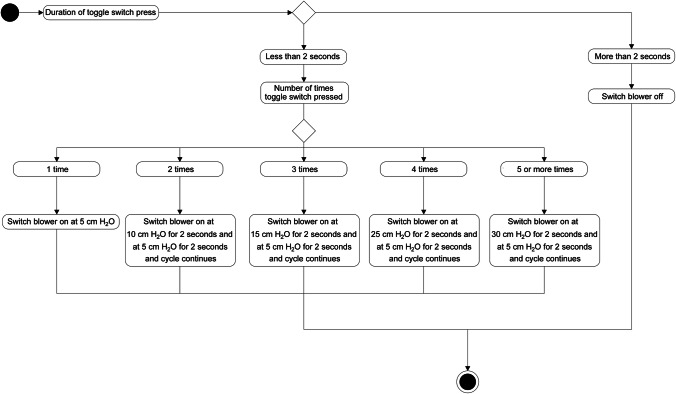

BiPAP is a mode of ventilation which maintains positive pressure for air intake, called inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and a low or zero pressure is created for expiration which is known as expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) or positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). The critical part of the BiPAP is the microcontroller which dictates the flow of air into the mask. An Arduino is selected as the microcontroller because of its easy to use features and open-source software. A brushless DC air blower is connected to the Arduino via an electronic speed controller, the circuit diagram is shown in Fig. 2. Prior to the entry to the mask the air flows through a pressure relief valve which prevents the inlet pressure to increase beyond 40 cm H2O, the pressure relief valves are commercially available and are frequently used in manual ventilators. The valve can easily be disabled in case of high pressure requirements for emergency cases. The electronic speed controller provides commands to the motor present in the blower, and these commands are programmed in the Arduino. The BiPAP cycle maintains a breathing rate of about 16 breaths per minute which is considered normal for a healthy adult (Cretikos et al. 2011). Hence, the blower will be programmed to create IPAP for 2 s and PEEP 2 s, and this BiPAP cycle is continued (Fig. 3). The toggle switch is used to vary the IPAP to 5 or more levels while the PEEP is kept constant. The IPAP range is targeted to vary from 5 to 30 cm H2O, and the PEEP is kept at 5 cm H2O. The pressure range is kept below 30 cm H2O to prevent tissue damage. The selection of the blower is critical because tidal volume requirement of the lungs has to be fulfilled while preventing lung-related injury. The tidal volume is intended to be kept below 6 ml/kg, which is considered a general practice in anaesthesiology (Putensen and Wrigge 2007). The proposed BiPAP operates in the pressure-controlled mode. The aforementioned information will be programmed in the Arduino whose activity diagram is mentioned in Fig. 4.

Fig. 2.

BiPAP design flow diagram

Fig. 3.

BiPAP pressure cycle

Fig. 4.

Activity diagram for BiPAP

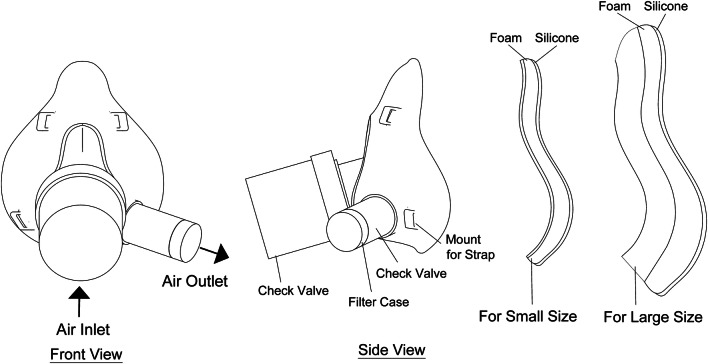

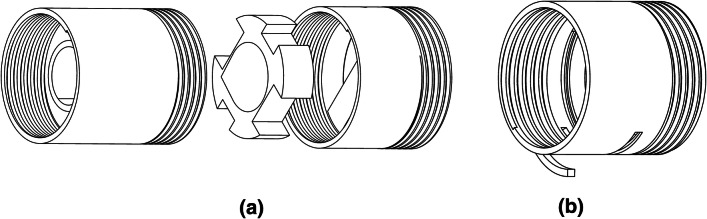

The detailed description of the mask is shown in Fig. 5, the mask is designed such that the bottom part is on the chin and the upper part is on the nose of the user. An add-on attachment is added to the mask body to vary the height of the mask as 115 mm and 85 mm for large and small sizes respectively to fit all adults. The range of critical dimensions of the mask body are provided in Table 1. The inlet port contains a check valve, which allows only incoming pressurized air from the air blower and no exhaled air is allowed to flow through this port to negate any probability of mixing of exhaled air with the incoming air and prevent any back flow. The inlet port diameter is larger as compared to conventional face masks to minimize the effect of increase in pressure due to the decreased area available as a result of the check valve mechanism. Beyond the check valve, the port opening is of standard size. The outlet check valve allows only the exhaust air to flow, the bigger size of exhaust valves compared to conventional mask allows for comfortable expiration of air as a result of decreased lung exertion. Immediately following the outlet check valve, a filter case is present, the check valves and the filter case are removable, which ensures easy access for cleaning and sterilization. To ensure a universal fit, a thick polyurethane foam layer is present, and as a result of its highly compressive nature the foam is able to compress around a wide variety of facial features. The shape of the mask body is designed to cover the basic facial features, the remaining sealing is ensured by the foam layer. The foam layer is followed by a silicone layer, which does not allow any air to escape, thus, creating a seal around the mask. Provisions for mask strapping around the face is available at the mounts on the mask body. The mask has to be strapped tightly to ensure proper fitting. PVC is selected as the material for mask body, check valve body and filter case because of its non-toxic nature, easy cleaning and easy manufacturability. The check valves at air inlet and outlet have the same working mechanism, the difference being that the direction of the allowed and blocked airflow is reversed and the diameter of inlet port is double that of the outlet port. The check valve and filter case are shown in Fig. 6. The check valve contains three parts, the middle part is the moving part which blocks the airflow in one direction and allows it in the opposite. Rubber coating the moving part ensure improved sealing effect of the mechanism. The filter case contains a hinge which opens up to facilitate easy replacing of the HEPA filter which is placed in the groove.

Fig. 5.

BiPAP mask

Table 1.

Dimensions of the BiPAP mask

| Part | Feature | Dimension range (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Outlet check valve | Diameter | 18–24 |

| Length | 24–30 | |

| Inlet check valve | Diameter | 32–38 |

| Length | 46–52 | |

| Filter case | Diameter | 19–25 |

| Length | 14–20 | |

| Small size attachment | Height | 80–85 |

| Width | 65–70 | |

| Large size attachment | Height | 110–115 |

| Width | 90–95 |

Fig. 6.

a Check valve and b filter case of BiPAP mask

Device Testing and Upscaling

The prototype has to undergo pressure and tidal volume testing, pressure testing using a simple U-tube manometer and the volumetric capacity during BiPAP operation measured by a flow meter is satisfactory. Reliability tests have to be performed to ensure that the device is suited for long term use. On-site testing and approval by experts are crucial for the success of the device. The final BiPAP has to comply with various standards including IEC 60601-1 (General Requirements for Basic Safety and Essential Performance of Medical Electrical Equipment), ISO 80601-2-70 (Sleep Apnea Breathing Therapy Equipment), etc. before the product is launched. To upscale the prototype to the product stage requires design and material changes provided by experts from the industry. In the final product, the 3D printed parts should be redesigned to comply with conventional manufacturing processes. Similarly, the microcontroller and motor controller are selected as per mass production requirements.

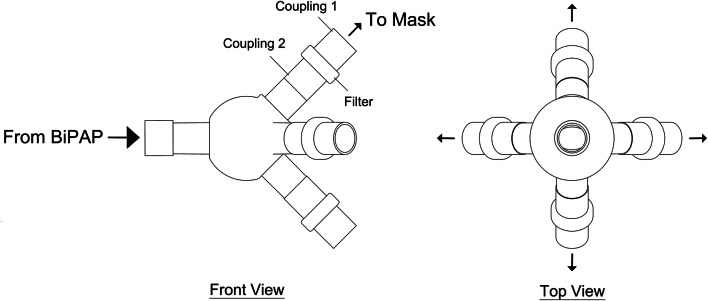

The prototype, as defined until now, is intended for a single patient because of the small capacity blower, but by doing few modifications in the design, i.e. by increasing the blower capacity and modifying the blower inlet, a single BiPAP is able to support four patients simultaneously. The modification is done by including a fitting onto the outlet of the blower which splits it into four, hence, a single blower is used to supply four patients. The design for this modification is shown in Fig. 7, coupling mechanism is used to connect the mask inlet tubes to the fitting and the other end is connected to the BiPAP blower outlet. The fitting contains a filter which ensures that the inhaled air is not infected to prevent cross contamination. Although the fitting attachment requires an increased capacity blower, the overall cost of providing respiratory support is significantly reduced as a single machine supports multiple patients simultaneously. The high pressure and low pressure settings of the BiPAP have to be modified according to the number of patients being supplied. If only two patients need to be supported, two of the ports are closed off and the pressures maintained are half of the required pressure for four patients. Since the BiPAP is intended to be used for non critical pressure which is lower than the traditional ventilator pressure, the multi-patient setup is much safer. Furthermore, the minimal components lead to an easy setup for multiple patient support. The BiPAP has to undergo further testing and trials to add these modifications in the final design.

Fig. 7.

BiPAP outlet fitting

Novelty in Design Technology

A tweaked BiPAP is proposed with:

A replaceable filter connected to the outlet valve of the mask to entrap the airborne disease causing particles.

A BiPAP machine that can support up to four patients simultaneously.

Timeline

A fully functional tweaked device is possible in 4 months. Successfully developing a BiPAP requires interdisciplinary collaborations. The design team should comprise of engineers to tackle the machinal and electrical aspects, the output parameters and practical design complexities have to be handled by medical professionals. The prototype requirements include brushless DC air blower, Arduino nano, electronic speed controller, DC power supply, toggle switch, pressure relief valve, HEPA filter, connecting tubes and other miscellaneous parts. The remaining components including mask, check valves and filter case are intended to be 3D printed. The pressure and volume testing facilities are available at various educational institutes or private labs, while on-site testing has to be performed in hospitals. Expansion to the product stage will require additional modifications provided by industry experts. A comprehensive business model has to be developed to acquire funding for the capital required to set up the production of the final product.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented a massive challenge to healthcare services around the globe which requires innovative and immediate solutions. The BiPAP machine proposed in the current article aims to deliver an economical and user-friendly respiratory support for non-critical patients and a backup resource for hospitals facing ventilation shortage. The final BiPAP design can support four patients simultaneously and has filtration for both inlet and outlet air to minimize the risk of infection. The mass-produced BiPAP should cost approx. INR 6500 or 85 USD.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Indian Institute of Technology Ropar and MHRD (Ministry of Human Resource Development), Government of India for providing PhD scholarship.

Author contributions

Gaurav Pal Singh: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft, formal analysis. Neha Sardana: conceptualization, resources, writing—review and editing, formal analysis, supervision.

Funding

The authors are grateful to Indian Institute of Technology Ropar and MHRD (Ministry of Human Resource Development), Government of India for providing PhD scholarship.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Gaurav Pal Singh, Email: gaurav.19mmz0003@iitrpr.ac.in.

Neha Sardana, Email: nsardana@iitrpr.ac.in.

References

- Arca MJ, Uhing M, Wakeham M. Current concept in acute respiratory support for neonates and children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2015;24:2–7. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskauf C, Nalpathanchil L (2020) Connecticut innovators take on COVID-19. https://www.wnpr.org/post/connecticut-innovators-take-covid-19. Accessed 01 Jun 2020

- Castro-Codesal ML, Olmstead DL, MacLean JE. Mask interfaces for home non-invasive ventilation in infants and children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2019;32:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): cases in U.S. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html. Accessed 20 Apr 2020

- Cretikos MA, Bellomo R, Hillman K, Chen J, Finfer S, Flabouris A. Respiratory rate: the neglected vital sign. Med J Aust. 2011;188(11):657–659. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECRI (2020) Single ventilator use to support multiple patients. https://assets.ecri.org/PDF/COVID-19-Resource-Center/COVID-19-Clinical-Care/COVID-ECRI_HTA_Single-Ventilator-Use-Multiple-Patients.pdf. Accessed 01 Jun 2020

- Kim GT, Ahn YC, Lee JK. Characteristics of Nylon 6 nanofilter for removing ultra fine particles. Korean J Chem Eng. 2008;25:368–372. doi: 10.1007/s11814-008-0061-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neyman G, Irvin CB. A single ventilator for multiple simulated patients to meet disaster surge. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(11):1246–1249. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poponick JM, Renston JP, Emerman CL. Successful use of nasal BiPAP in three patients previously requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(6):785–788. doi: 10.1016/S0736-4679(97)00185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putensen C, Wrigge H. Tidal volumes in patients with normal lungs: one for all or the less, the better? Anesthesiology. 2007;106(6):1085–1087. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000265424.07486.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer TH, Alapati D, Greenspan JS, Wolfson MR. Neonatal non-invasive respiratory support: physiological implications. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47:837–847. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet (Editorial) COVID-19: too little, too late? Lancet. 2020;395(10226):755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30522-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank (2020) Hospital beds (per 1,000 people). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sh.med.beds.zs. Accessed 20 Apr 2020

- Vitality Medical (2020) Full face masks. https://www.vitalitymedical.com/full-face-masks-cpap.html. Accessed 01 Jun 2020

- Wilke LD, Ghamande S. Mask interfaces. Sleep Med Clin. 2013;8:477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2013.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]