Abstract

Despite the advancement of immunotherapy in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer, patients with poor performance status (PS) have been excluded from clinical trials and it is unknown if the benefit exists in this cohort. Our retrospective study showed that immunotherapy is an active regimen in patients with poor PS, however, inferior survival outcomes were noted when compared to medically fit patients.

Introduction:

Immunotherapy has become a key treatment for patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). While a survival advantage has been proven for patients who are medically fit, it is unknown whether a benefit exists for patients with poor performance status (PS).

Patients and Methods:

We performed a retrospective analysis of NSCLC patients who received immunotherapy in our health system. Age and PS at the time of initial immunotherapy administration were assigned based on physician documentation. Radiographic response and date of progression were assigned according to the treating physician’s assessment and confirmed by the study team. Immune-related adverse events were extracted from records.

Results:

We identified 285 NSCLC patients who received immunotherapy between January 2014 and April 2018. In this group, 153 patients (53.7%) had PS 0–1, 114 (40.0%) had PS 2, and 18 (6.3%) had PS 3. Response rates were similar across PS groups with 26.6% for PS 1, 25.2% for PS 2, and 23.1% for PS 3 (P = .95). Survival outcomes varied with pretreatment PS. For PS 0–1, PS 2, and PS 3, median overall survival was 14.7, 8.3, and 1.5 months (P < .001), and progression-free survival was 7.4, 5.1, and 1.3 months (P < .001). Patients aged < 70 had a lower rate (7.6%) of immune-related adverse events requiring steroids compared to patients ≥ 70 (15%) (P = .04).

Conclusion:

Patients with poor baseline PS demonstrate similar response rate but inferior progression-free survival and overall survival compared to medically fit patients. Prospective trials are needed to optimize treatment for this large population.

Keywords: Elderly, ICU admissions, Immune-related adverse events, Programmed death receptor inhibitor, Steroids

Introduction

Drugs targeting the programmed death 1 (PD-1) receptor and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) have demonstrated survival benefits for patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Pembrolizumab is now considered a standard of care in the front-line setting either in combination with chemotherapy or as monotherapy for patients with PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) above 50%. While immunotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy have changed the current treatment paradigm, most published studies restricted participation to medically fit patients.1–7 The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) is known to predict outcomes for patients receiving chemotherapy.8 Given the toxicity profile of immunotherapy it is unclear if the ECOG scale will continue to have predictive value when using this newer class of drugs.

PS has been established as one of the most powerful independent prognostic factors in advanced NSCLC since it is a strong predictor of survival and adverse events.8 When treated with conventional chemotherapy, patients with PS 2 and 3 have worse outcomes and higher rates of toxicity which is why they have been excluded from many clinical trials.9,10 Standard treatment is generally recommended in patients with PS 0–1, while best supportive care is offered to patients with PS 4. Clinical trials are needed to define the best practices for patients with PS 2 and PS 3. Prior studies indicate that patients with PS 2 and PS 3 account for approximately 30% and 15% of lung cancer patients representing a substantial population without sufficient representation in randomized trials.11

Lung cancer is predominantly a disease of older adults12 with approximately 50% of lung cancers diagnosed in patients at least 70 years of age with 15% older than 80 years of age.13 Advanced age alone does not predict for a lack of clinical benefit in most studies with cytotoxic chemotherapy.14–16 However, increasing age does predict a higher risk of chemotherapy toxicities.17 For immunotherapy, subgroup analyses (≥65 vs. < 65 years old) from 3 registration trials have shown no difference3 or decreased survival benefit for elderly patients (≥ 65 years old).5 There are a limited number of immunotherapy clinical trials dedicated to the elderly, potentially putting such patients at risk for undertreatment and overtreatment biases.18

Given a more favorable toxicity profile, it is possible that immunotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors would be an acceptable treatment regimen in patients with poor PS and in adults of advanced age. In this retrospective study, we analyzed patients with advanced NSCLC who were treated with immunotherapy at our institution and investigated survival outcomes and adverse events based on PS and age.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wake Forest University. We reviewed the medical records for all patients with a diagnosis of lung cancer and who were treated with immunotherapy between January 01, 2014 and April 1, 2018. Data were collected by chart review. Inclusion criteria were: age at start of immunotherapy > 18 years, diagnosis of Stage IV NSCLC, and administration of immunotherapy (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, atezolizumab or ipilimumab) within our health system.

Patient characteristics reviewed included date of birth, date of initiation of immunotherapy, sex, race, smoking status, line of therapy (counting systemic therapies given for metastatic disease), ECOG PS, PD-L1 TPS, next-generation sequencing (NGS) for cancer-associated genetic alterations detected either in peripheral blood (Guardant360, Guardant Health) or tumor samples (FoundationOne, Foundation Medicine or Caris, Caris Life Sciences), date of immunotherapy administration, number of cycles, date of progression, best response, date of death, reason for discontinuation of immunotherapy, hospital admissions in our health system, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions in our health system, length of stay during hospital and ICU admissions, and steroid use for immune-related adverse events (irAE) including pneumonitis, colitis, nephritis, hepatitis, adrenal insufficiency, rash, hyper-/hypothyroidism, hypophysitis, arthralgia/arthritis, and other significant toxicities.

Age was determined at the date of initiation of immunotherapy. The ECOG PS that was used in our study was the PS that was documented at the date of initial immunotherapy administration. If the patient was not seen in clinic on the day of administration, the PS of the most recent prior clinic visit was used. For the purposes of analysis, we categorized PS scores into 3 groups: 0–1, 2, or 3.

Response Assessment

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of initial immunotherapy administration to the date of death or last follow-up. Patients who were alive at the date of last contact were censored at that time point. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the date of initial immunotherapy administration to the date of progression or death. Date of progression was determined clinically by the treating physician as documented in the medical chart. Overall response was defined as obtaining a partial response or complete response (CR) which was not typically specified in the medical chart by the treating physician, therefore responses were independently categorized according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines19 by a study team physician from medical oncology (T.A., T.L., A.D.).

Statistical Analysis

We first examined basic sample characteristics after stratifying by PS level (0–1, 2, and 3). We computed basic frequencies for categorical variables and medians for continuous variables. Differences in frequencies across PS strata were tested with the chi-square and Fisher exact test. Differences in medians were tested using the Kruskal-Wallis test. We also examined differences in outcomes (median OS, median PFS, overall response rate, and variables related to steroid use for adverse events and to hospitalizations) stratified both by PS level and then by age group (< 70 vs. ≥70 years at start of immunotherapy). Differences in median survival were tested with the log-rank test (based on Kaplan-Meier time-to-event curves) while differences in means were tested with F-tests from analyses of variance. Finally, we ran Cox proportional hazards models treating both PFS and OS as outcomes and considering PS level (in 3 nominal categories) and age at start of immunotherapy (as a continuous variable) as predictors, while also including key covariates of smoking status (never, current, or former) and line of therapy (first through fourth). A 2-tailed alpha level of .05 was used throughout. All analyses were performed by SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 285 patients with NSCLC were treated with immunotherapy between January 2014 and April 2018. Patient characteristics stratified by PS level are summarized in Table 1. One hundred fifty-three patients (53.7%) had an ECOG PS of 0–1, 114 (40.0 %) had a PS of 2, and 18 patients (6.3%) had a PS of 3. The median age at start of immunotherapy was related to PS, with those with less favorable PS levels having a higher median age (P = .007). There were no significant differences in the frequencies of PS groups among patients who were less than 70 years of age and those 70 years old and over. Most patients were white and were current or former smokers with nonsquamous histology. None of these variables differed significantly by PS group. Combination chemotherapy/immunotherapy (45 patients; 16%) was only given in the first line of treatment. There was a significant difference (P = .03) in PD-L1 TPS, with those with the best PS the most likely to have PD-L1 TPS less than 50%. The majority of patients in each group did not have an available PD-L1 TPS documented in the medical record. Patients with PS of 3 were more likely to receive pembrolizumab monotherapy and received fewer cycles of immunotherapy than those with more favorable PS scores. No cases of hyper-progression were identified.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by ECOG PS

| Characteristic | PS 0–1 | PS 2 | PS 3 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 153 (53.7) | 114 (40.0) | 18 (6.3) | |

| Age (y) | 64.5 (38.3–91.1) | 67.7 (47.1–86.8) | 68.7 (50.9–92.0) | .007a |

| Age Group | ||||

| <70 y | 108 (70.6) | 67 (58.8) | 10 (55.6) | .07 |

| ≥70 y | 45 (29.4) | 47 (41.2) | 8 (44.4) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 84 (54.9) | 68 (59.7) | 7 (38.9) | .24 |

| Female | 69 (45.1) | 46 (40.4) | 11 (61.1) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 124 (81.1) | 98 (86.0) | 16 (88.9) | .71b |

| African American | 26 (17.0) | 13 (11.4) | 2(11.1) | |

| Other | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.6) | 0 | |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Current | 26 (17.0) | 30 (26.3) | 4 (22.2) | .43b |

| Former | 110 (71.9) | 72 (63.2) | 13 (72.2) | |

| Never | 17(11.1) | 12 (10.5) | 1 (5.6) | |

| Histology | ||||

| Nonsquamous | 110 (71.9) | 72 (63.2) | 12 (66.7) | .31 |

| Squamous | 43 (28.1) | 42 (36.8) | 6 (33.3) | |

| PD-L1 TPS | ||||

| <50% | 25 (16.3) | 6 (5.3) | 1 (5.6) | .03b |

| ≥50% | 19 (12.4) | 20 (17.5) | 4 (22.2) | |

| Not available | 109 (71.2) | 88 (77.2) | 13 (72.2) | |

| Immunotherapy Regimen | ||||

| Pembrolizumab | 18 (11.8) | 28 (24.6) | 7 (39.9) | <.0001b |

| Nivolumab | 96 (62.8) | 68 (59.7) | 11 (61.1) | |

| Atezolizumab | 2(1.3) | 2(1.8) | 0 | |

| Pembrolizumab + carboplatin + pemetrexed | 29 (19.0) | 6 (5.3) | 0 | |

| Pembrolizumab + carboplatin + paclitaxel | 0 | 10 (8.8) | 0 | |

| Other | 5 (4.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Line of Treatment | ||||

| First | 37 (24.2) | 34 (29.8) | 6 (33.3) | .17 |

| Second | 94 (61.4) | 59 (51.8) | 6 (33.3) | |

| Third | 15 (9.8) | 16 (14.0) | 4 (22.2) | |

| Fourth or higher | 7 (4.6) | 5 (4.4) | 2(11.1) | |

| No. of doses received | 7(1–57) | 5 (1–53) | 1.5 (1–36) | <.0001a |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range).

Abbreviations: ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PD-L1 = programmed death ligand 1; PS = performance status; TPS = tumor proportion score.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Fisher exact test.

Outcomes by PS

The median OS for patients with a PS of 0–1 was 14.7 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 11.83 to [unestimable upper limit] months) while the median OS for patients with PS of 2 and 3 were 8.3 months (95% CI, 5.0–12.4) and 1.5 months (95% CI, 1–4.9) (Figure 1A). The differences in OS indicate significantly shorter OS with increasing PS (P < .0001) (Table 2).

Figure 1. (A) OS and (B) PFS by PS.

Abbreviations: OS = overall survival; PFS = progression-free survival; PS = performance status.

Table 2.

Survival by ECOG PS and Age

| PS | Age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 0–1 | 2 | 3 | P | <70 Years | ≥70 Years | P |

| OS (months), median 95% CI) | 14.7 (11.8−) | 8.3 (5.0–12.4) | 1.5 (1.0–4.9) | <.0001a | 12.4 (9.4–14.4) | 10.3 (5.8−) | .77a |

| PFS (months), median (95% CI) | 7.4 (5.7–12.2) | 5.1 (3.2–6.7) | 1.3 (1.0–4.9) | .0003a | 6.0 (3.9–6.6) | 6.7 (4.8–12.1) | .14a |

| Response, n (%) | 38 (26.6) | 27 (25.2) | 3 (23.1) | .95b | 40 (23.0) | 28 (31.5) | .14b |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; OS = overall survival; PFS = progression-free survival; PS = performance status.

Log-rank test.

Chi-square test.

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1B, PFS also worsened with increasing PS (P = .0003). Patients with a PS of 0–1, 2, and 3 demonstrated median PFS of 7.4 months (95% CI, 5.7–12.2), 5.1 months (95% CI, 3.2–6.7), and 1.3 months (95% CI, 1.0–4.9). Radiographic response rates between the PS groups were not significantly different (PS 0–1, 2, and 3 were 26.6%, 25.2%, and 23.1% respectively, P = .95).

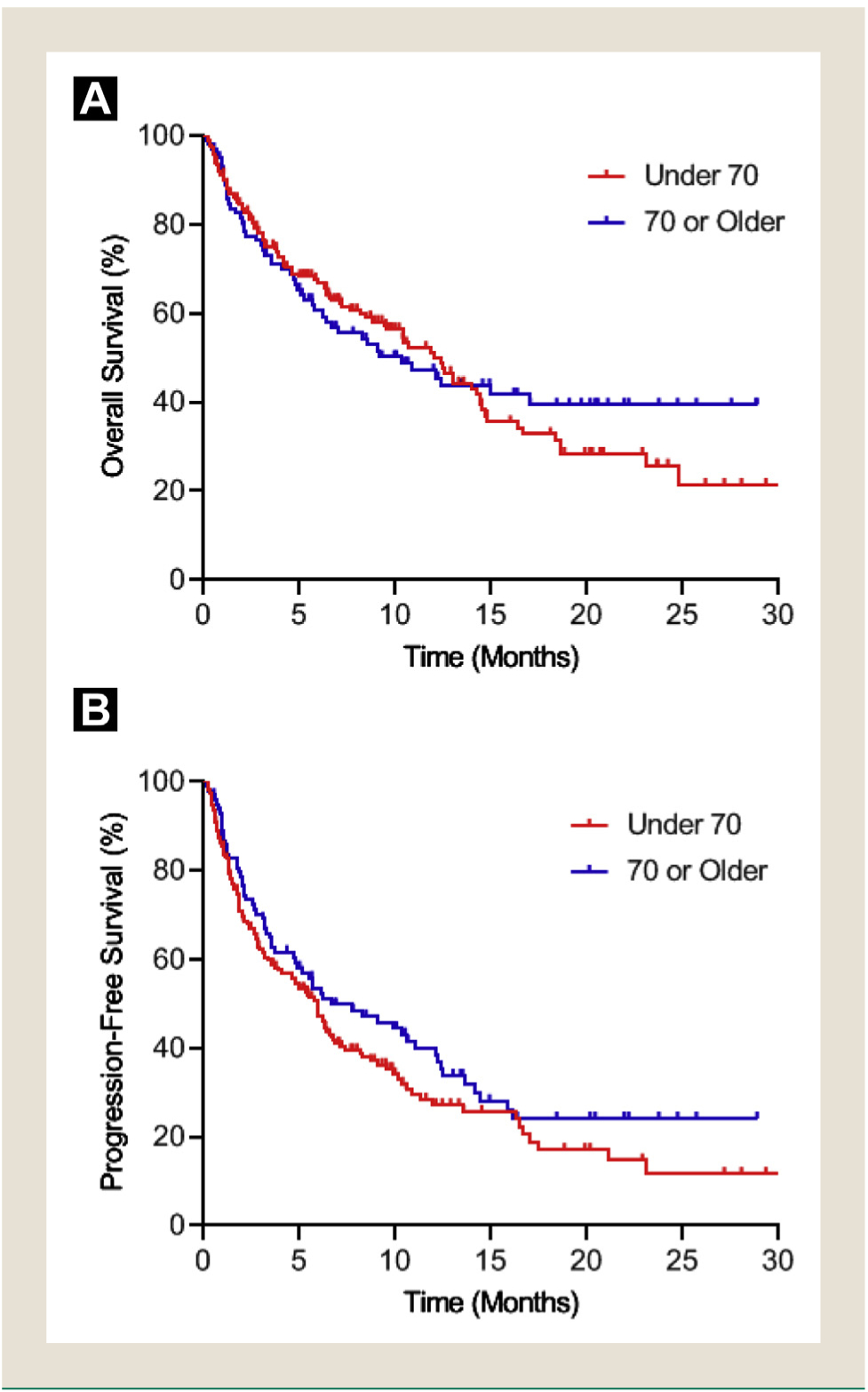

Outcomes by Age

The OS, PFS, and overall response did not differ significantly by age group (Table 2). Patients less than 70 years old had an OS of 12.4 months (95% CI, 9.4–12.4) while patients 70 years old and over had an OS of 10.3 months (95% CI, 5.8-[inestimable upper limit]; P = .77) (Figure 2A). The PFS of younger as compared to older age groups were similar with 6.0 months (95% CI, 3.9–6.6) versus 6.7 months (95% CI, 4.8–12.1; P = .18) (Figure 2B). The response rate in the younger cohort was lower at 23% compared to the older cohort at 31.5% but this difference was not statistically significant (P = .14).

Figure 2. (A) OS and (B) PFS by Age.

Abbreviations: OS = overall survival; PFS = progression-free survival.

Outcomes by Oncogene Status

NGS testing for cancer-associated genetic alterations was obtained in 154 patients (54%) and found KRAS mutations in 49 patients (32% of NGS-tested patients) and STK11 mutations in 14 patients (9% of NGS-tested patients), including variants of unknown significance. Among the subgroup of NGS-tested patients, PS distribution was not markedly different among patients with a KRAS mutation (PS0–1, 57%; PS2, 36%; PS3, 6%) or a STK11 mutation (PS0–1, 71%; PS2, 29%). Response rate was 23% (11/47) among patients with a KRAS mutation and 23% (3/13) among patients with a STK11 mutation.

Adverse Events

There were 15 patients (9.8%) in the PS 0–1 group that developed irAE which required steroids (Table 3). In this group, the irAEs experienced included pneumonitis (n = 5), colitis (n = 3), dermatitis (n = 3), nephritis (n = 2), arthritis (n = 1), and nerve palsy (n = 1). In the PS 2 group, there were 10 patients (8.8%) who developed an irAE which required steroids including pneumonitis (n = 1), colitis (n = 3), dermatitis (n = 3), hepatitis (n = 1), hyponatremia (n = 1) and myasthenia gravis (n = 1). Those with PS 3 were the most likely to experience an adverse event requiring steroids, though the difference did not reach statistical significance. In the PS 3 group, 4 patients (22.2%) developed an irAE which required steroids (pneumonitis, dermatitis, hepatitis, and arthritis). Those who did require steroid use in the PS 3 group were on steroids for a significantly longer time than patients requiring steroids in either of the other 2 PS groups (P = .004). There were no significant differences among the PS groups in number of general or ICU hospitalizations, or the number of days spent in hospital or ICU. In the PS 0–1, 2, and 3 groups, 12 patients (7.8%), 6 patients (5.3%), and 0 patients discontinued immunotherapy treatment due to an irAE (P = .16). There was only one patient death (PS 2 and age ≥ 70) attributed to an irAE (myasthenia gravis) in the entire population.

Table 3.

Adverse Events by ECOG PS and Age

| PS | Age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 0–1 | 2 | 3 | P | <70 Years | ≥70 Years | P |

| irAE requiring steroid | 15 (9.8) | 10 (8.8) | 4 (22.2) | .21 | 14 (7.6) | 15 (15.0) | .05 |

| Duration of steroid use (days), mean (SD) | 7.0 (30.5) | 5.7 (21.7) | 37.1 (108.9) | .004 | 6.7 (38.5) | 11.5 (37.2) | .31 |

| No. of hospital admissions, mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.7 (1.4) | .54 | 1.0 (1.6) | 0.9 (1.3) | .57 |

| Total days of hospitalization, mean (SD) | 4.5 (8.2) | 4.7 (8.4) | 3.2 (6.7) | .76 | 4.8 (8.3) | 4.0 (7.8) | .47 |

| No. of ICU admissions, mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.4 (1.0) | .18 | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.4) | .04 |

| Total days in ICU, mean (SD) | 1.0 (2.9) | 0.5 (1.7) | 1.0 (2.0) | .26 | 1.0 (2.8) | 0.4 (1.3) | .007 |

| Discontinued treatment due to irAE, n (%) | 12 (7.8) | 6 (5.3) | 0 | .36 | 8 (4.3) | 10 (10.0) | .06 |

Abbreviations: ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ICU = intensive care unit; irAE = immune-related adverse event; PS = performance status; SD = standard deviation.

There was a significant difference in the proportion of patients in the younger and older groups who developed an irAE requiring steroid treatment (Table 3). Fourteen patients (7.6%) in the younger group required steroid treatment, compared to 15 patients (15%) in the older group. There was no significant difference between the age groups in duration of steroid use or general hospital admissions. Patients in the younger age group had significantly more ICU admissions and spent more days in the ICU compared to the older age group (P = .04 for ICU admissions and P = .007 for ICU days). Eight patients (6.0%) in the younger age group and 10 patients (13.3%) in the older age group discontinued treatment due to an irAE (P = .07).

Line of Treatment and Smoking Status in Multivariate Analysis

Table 4 shows results from multivariable regression models for the 3 main outcomes of interest. In a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model of OS considering both PS level and age as predictors of interest and including smoking status and therapy line as covariates, both PS level 2 and level 3 had significantly worse OS relative to the referent group of PS level 0–1 (Table 2). This also held in the proportional hazards model for PFS. The lack of predictive value of age for either OS or PFS also persisted after adjusting for PS level. In both models, current and former smokers had better survival than did the never smokers. We modeled overall response as a dichotomous outcome with a logistic regression model, and while the 2 higher PS levels were associated with lower odds of response compared to the referent PS level of 0–1, neither of the differences reached statistical significance. In this model as well, age was not significantly associated with response rate after adjusting for PS.

Table 4.

Associations Between Variables at Start of Immunotherapy and Main Outcomes

| Characteristic | PFS (Months), HR (95% CI)a | OS (Months), HR (95% CI)a | Overall Response, OR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG PS | |||

| 0–1 | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| 2 | 1.65 (1.21–2.26)c | 2.03 (1.42–2.90)c | 0.84 (0.46–1.52) |

| 3 | 3.02 (1.72–5.30)c | 5.42 (3.02–9.71)c | 0.65 (0.16–2.62) |

| Age (years) at start of immunotherapy Smoking Status | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) |

| Never | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| Current | 0.43 (0.25–0.73)c | 0.48 (0.27–0.86)c | 3.72 (0.97–14.30) |

| Former | 0.43 (0.27–0.68)c | 0.44 (0.27–0.74)c | 2.73 (0.78–9.60) |

| Line of Therapy | |||

| 1 | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| 2 | 1.38 (0.95–2.02) | 1.73 (1.10–2.74) | 0.64 (0.33–1.23) |

| 3 | 1.41 (0.86–2.33) | 1.61 (0.90–2.88) | 0.73 (0.28–1.95) |

| 4 | 1.13 (0.54–2.37) | 1.28 (0.57–2.90) | 1.01 (0.27–3.72) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HR = hazard ratio; OR = odds ratio; OS = overall survival; PFS = progression-free survival; PS = performance status.

Cox proportional hazards model.

Logistic regression model.

Statistically significant (P < .05).

Discussion

Patients with advanced NSCLC who have PS 2 or 3 have been excluded from many clinical trials and determining the best course of treatment remains clinically challenging. Several studies have demonstrated that patients with poor PS experience increased toxicities and have poor survival outcomes when treated with conventional chemotherapy.20 Since the toxicity profile of immunotherapy differs from cytotoxic chemotherapy, it is possible that baseline PS will have less of an impact on predicting outcomes with immunotherapy. A recent meta-analysis supports this viewpoint and has identified similar survival benefits for patients with PS 0 and patients with PS 1–2 who are treated with immunotherapy.21 In the conclusion, the authors of this study suggested that immunotherapy could be offered to even the frailest of patients given the potential for favorable outcomes.

When comparing the PS 2 group to the PS 0–1 group, our analysis found similar radiographic response rates but inferior median PFS and OS. After adjusting for age and line of therapy, poor PS continued to predict worsened survival outcomes. This finding suggests that PS should remain a stratification factor for randomized immunotherapy trials where PFS or OS are primary endpoints. Our study found no differences in irAE requiring steroids, duration of steroid use, hospital admissions, days hospitalized, ICU admissions, days spent in the ICU, or treatment discontinuation due to irAE.

There is limited historical data to guide the use of immunotherapy in PS2 patients. The registration phase 3 immunotherapy trials for nivolumab,5,7 pembrolizumab,1–3 and atezolizumab21 excluded PS 2 patients. KEYNOTE-10 did not exclude patients with poor PS but their study only included 5 patients with PS 2 which was < 1% of the study population.6 Checkmate 153 is an ongoing phase 3B/4 safety trial of nivolumab which included 556 patients who were ≥ 70 years old and 128 patients who were PS2, with decreased efficacy noted among the PS2 subpopulation. Subgroup analyses for these 2 groups reported median OS of 10.3 and 4.0 months (9.1 months for overall population) and 2-year survival of 25% and 9% (26% in overall population). Safety in terms of incidence of high-grade (grade 3 to 5) treatment-related AEs was similar among the ≥ 70 years old (6%) and PS2 sub groups (9%) as compared to the overall population (6%).22 An ongoing American phase 2 trial of pembrolizumab in 60 PS2 patients (PePS2, NCT02733159) reported preliminary efficacy and safety data with overall response rate 30%, median PFS 4.4 months, and incidence of high-grade (grade 3/4) treatment-related AEs 8%.23 An ongoing European phase 2 trial of nivolumab (CheckMate 171, NCT02409368) also reported preliminary safety data which showed similar toxicity (treatment discontinuation due to treatment-related AE) among the ≥ 70-year-old subgroup (n = 279, 6%) and PS2 subgroup (n = 98, 5%) as compared to the overall population (n = 809, 6%).24 To provide context for our data, several historical studies of PS 2 patients were compiled and summarized in Table 5.22–28 Our results are not directly comparable due to the observational nature of our study. However, despite the majority of patients on our study being in the relapsed or refractory setting, the fact that survival outcomes are at the least on par if not better than those reported in front-line studies is promising.

Table 5.

Historical Studies of Patients With ECOG PS 2

| Characteristic | Our Study | CheckMate 15322 | PePS223 | CheckMate 17124 | Lilenbaum et al27 | STELLAR 328 | ECOG 159925 | AB0UND.PS226 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | immunotherapy | Nivolumab | Pembrolizumab | Nivolumab | Carboplatin, paclitaxel | Carboplatin, paclitaxel | Cispiatin, gemdtabine | Carboplatin, paclitaxe | Carboplatin, nab-paclitaxel |

| Prior systemic treatment | Yes | Yes | Yes (83%) | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| No. of subjects | 114 | 128 | 60 | 98 | 51 | 201 | 49 | 54 | 40 |

| Median OS (months) | 8.3 | 4.0 | NR | NR | 9.7 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 7.7 |

| Median PFS (months) | 5.1 | NRa | 4.4 | NR | 3.5 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 4.4 |

| RR | 27% | NR | 30% | NR | 12% | 37% | 23% | 14% | 30% |

| Incidence of high-grade (grade 3/4) irAE | 9% | 9% | 8% | 5%b | 41 %c | 40% | 15%b | 16%b | 75% |

Abbreviations: ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; irAE = immune-related adverse event; NR = not reported; OS = overall survival; PFS = progression-free survival; PS = performance status; RR = response rate.

Disease progression listed as reason for death in in 79% of patients.

Rate of treatment discontinuation due to treatment-related AE.

Included grade 5 (fatal) events in 2 patients (4%), both from febrile neutropenia

Our retrospective study validates immunotherapy as an active regimen in the PS 2 population. There are ongoing, prospective, phase 2 trials that are dedicated to patients with advanced NSCLC and PS 2 which may ultimately answer the question of immunotherapy in this population with pembrolizumab (NCT02733159) and durvalumab (NCT02879617).

Our study found 18 patients who had documented PS 3 prior to initiation of immunotherapy. The median OS and PFS were quite short in this cohort at 1.5 months and 1.3 months. When compared to the PS 3 subgroup in the TRUST study, erlotinib had similar survival outcomes with an OS and PFS of 1.8 months and 1.6 months.29 Immunotherapy for patients with very poor PS may seem like a viable option given the favorable toxicity profile when compared to cytotoxic chemotherapy, but our study does not provide strong support for this approach and best supportive care for PS 3 patients without a driver mutation continues to be a reasonable clinical approach.30 Further study of this population is needed. It is possible that better outcomes could be achieved for patients who have poor PS due to cancer compared who have poor PS due to comorbidities. As is done for small cell patient evaluations, subdividing PS 2 and 3 NSCLC patient cohorts according to the underlying cause of poor PS may be useful for future work in the field.

Although lung cancer is a disease of older adults, age alone has not been an established predictor for survival. Although the large phase 3 immunotherapy trials excluded patients with poor PS, age was evaluated in subgroup analyses.1,5–7 Our study evaluated older patients using 70 years as the cut-off and is consistent with prior studies finding no statistically significant difference in OS, PFS, and response rate between the 2 cohorts. We found that patients ≥ 70 years developed significantly more irAE which required treatment with steroids. It is unclear why there is a toxicity discrepancy in our population compared to the larger randomized trials. Providers in clinical practice may have a lower threshold to prescribe steroids in the elderly population given overtreatment bias. Although hospital admission between the age groups were similar, surprisingly, patients < 70 years of age had significantly higher ICU admissions and days spent in the ICU. Bias may have played a role in this discrepancy because providers thought that ICU admission in the elderly population would have been futile and not recommended. It is also possible that the more frequent administration of steroids in the elderly may have prevented ICU admissions. Further dedicated studies to irAE toxicities and outcomes are needed, but providers may need to have just as low of a threshold to prescribe steroids in younger patients as compared to the elderly to prevent ICU admissions.

Our retrospective study has limitations. Since our data were collected by chart review, we were limited by provider’s documentation of events that occurred. Toxicity was difficult to ascertain by this method alone which is why we collected data on patients who were administered steroids after initiation of immunotherapy and determined by chart review if this was given for an irAE. Thus, we were not able to evaluate patients who developed low-grade toxicities not requiring steroids. We also did not capture patients who developed hypo-thyroidism requiring thyroid replacement treatment. However, we thought that if an irAE occurred and required steroid administration, then it was deemed to be clinically significant. There were limited PD-L1 results available due to the timing of this real-world retrospective cohort with half of the patients starting immunotherapy in 2015–2016 with nivolumab as a later line of therapy, a situation when PD-L1 testing was not a routine part of clinical management. Despite their poor PS, our providers thought the patients were good candidates for immunotherapy leading to possible selection bias that could limit the generalizability of these findings. Another limitation is that we included all immunotherapy regimens, PD-L1 levels, and lines of therapy together when evaluating the PS. This led some heterogeneity among the different PS groups. The multivariate analysis examined the contributions of these factors and found that the findings held after correction for these.

In conclusion, our retrospective study demonstrated that PS is a predictive factor of survival outcomes in patients with advanced NSCLC receiving immunotherapy. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors appear to be well-tolerated and active regimen in patients with PS 2. Given the apparent benefit, inclusion of PS 2 patients should be strongly considered in phase 3 trials with immunotherapy going forward. However, PS should be considered as a stratification factor to avoid the potential for imbalances in arms impacting OS and PFS.

Clinical Practice Points.

Although, immunotherapy has changed the landscape of how we treat advanced NSCLC, it has largely only been studied in medically fit patients with good PS (0 or 1).

PS is a strong independent predictor of survival and adverse events, which is why patients with poor PS have historically been excluded from clinical trials. It is unknown if PS will retain its status as powerful prognostic factor in the era of immunotherapy.

Our retrospective study of 285 patients with advanced NSCLC treated with immunotherapy demonstrated that indeed patients with poor PS did worse when compared to patients with good PS even when accounting for age, line of therapy, and smoking status as covariables in a multivariate analysis.

With favorable survival outcomes in the PS 2 group, our study validates immunotherapy as an active regimen in this population. Despite no difference in survival outcomes between younger and older adults, we did find that older adults had more steroid requiring irAE compared to younger adults.

Although large randomized prospective trials are needed for validation, our study shows that immunotherapy is an active regimen in patients with poor PS.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have stated that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1epositive non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:1823–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:2078–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:2040–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:2288–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1627–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1epositive, advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387:1540–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:123–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sculier JP, Chansky K, Crowley JJ, Van Meerbeeck J, Goldstraw P, International Staging Committee and Participating Institutions. The impact of additional prognostic factors on survival and their relationship with the anatomical extent of disease expressed by the 6th edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors and the proposals for the 7th edition. J Thorac Oncol 2008; 3:457–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunn PA. Chemotherapy for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: who, what, when, why? J Clin Oncol 2002; 20(18 suppl):23S–33S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tartarone A, Aieta M. Treatment of performance status 2 patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: what we know and what we don’t know. Future Oncol 2009; 5:837–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lilenbaum RC, Cashy J, Hensing TA, Young S, Cella D. Prevalence of poor performance status in lung cancer patients: implications for research. J Thorac Oncol 2008; 3:125–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel RL,Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owonikoko TK, Ragin CC, Belani CP, et al. Lung cancer in elderly patients: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:5570–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langer CJ, Manola J, Bernardo P, et al. Cisplatin-based therapy for elderly patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: implications of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 5592, a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94:173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belani CP, Fossella F. Elderly subgroup analysis of a randomized phase III study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for first-line treatment of advanced nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (TAX 326). Cancer 2005; 104:2766–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hensing TA, Peterman AH, Schell MJ, Lee JH, Socinski MA. The impact of age on toxicity, response rate, quality of life, and survival in patients with advanced, stage IIIB or IV nonsmall cell lung carcinoma treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Cancer 2003; 98:779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veluswamy RR, Levy B, Wisnivesky JP. Chemotherapy in elderly patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2016; 22:336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, Grove L, Spitznagel EL. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA 2004; 291:2441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 228–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sweeney CJ, Zhu J, Sandler AB, et al. Outcome of patients with a performance status of 2 in Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E1594: a Phase II trial in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 2001; 92: 2639–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non–small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 389:255–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spigel DR, McCleod M, Jotte RM, et al. Safety, efficacy, and patient-reported health-related quality of life and symptom burden with nivolumab in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer, including patients aged 70 years or older or with poor performance status (CheckMate 153). J Thorac Oncol 2019; 14: 1628–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Middleton G, Brock K, Summers Y, et al. Pembrolizumab in performance status 2 patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): results of the PePS2 trial. Poster discussion presented at: European Society of Medical Oncology Congress; October 19–23, 2018; Munich, Germany, Available at: https://oncologypro.esmo.org/meeting-resources/ESMO-2018-Congress/Pembrolizumab-in-performance-status-2-patients-with-non-small-cell-lung-cancer-NSCLC-results-of-the-PePS2-trial. Accessed: January 31, 2020.

- 24.Popat S, Ardizzoni A, Ciuleanu T, et al. Nivolumab in previously treated patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC: results of a European single-arm, phase 2 trial (CheckMate 171) including patients aged ≥ 70 years and with poor performance status. Paper presented at: European Society for Medical Oncology; September 10, 2017; Madrid, Spain, Available at: https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article/28/suppl_5/mdx380.006/4109361. Accessed: January 31, 2020.

- 25.Langer C, Li S, Schiller J, et al. Randomized phase II trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin or gemcitabine plus cisplatin in Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 2 non–small-cell lung cancer patients: ECOG 1599. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:418–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gajra A, Karim NA, Mulford DA, et al. Paclitaxel-based therapy in underserved patient populations: the ABOUND.PS2 study in patients with NSCLC and a performance status of 2. Front Oncol 2018; 8:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lilenbaum R, Axelrod R, Thomas S, et al. Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib or standard chemotherapy in patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer and a performance status of 2. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:863–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lilenbaum R, Villaflor VM, Langer C, et al. Single-agent versus combination chemotherapy in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer and a performance status of 2: prognostic factors and treatment selection based on two large randomized clinical trials. J Thorac Oncol 2009; 4:869–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Meerbeeck J, Galdermans D, Bustin F, De Vos L, Lechat I, Abraham I. Survival outcomes in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer treated with erlotinib: expanded access programme data from Belgium (the TRUST study). Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2014; 23:370–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: non–small cell lung cancer, version 2.2018, Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed: January 31, 2020.