Abstract

Objective:

Concerns over resident ability to practice effectively after graduation have led to the competency-based medical education movement. Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) may facilitate competency-based medical education in surgery, but implementation is challenging. This manuscript describes one strategy used to implement EPAs into an academic general surgery residency.

Design, Setting, Participants:

A mobile application was developed incorporating five EPAs developed by the American Board of Surgery; residents and faculty from the Departments of Surgery, Emergency Medicine, and Hospital Medicine at a single tertiary care center were trained in its use. Entrustment levels and free text feedback were collected. Self-assessment was paired with supervisor assessment, and faculty assessments were used to inform clinical competency committee entrustment decisions. Feedback was regularly solicited from app users and results distributed on a monthly basis.

Results:

1720 microassessments were collected over the first 16 months of implementation; 898 (47.8%) were performed by faculty with 569 (66.0%) matched pairs. Engagement was skewed with small numbers of high performers in both resident and faculty groups. Continued development of resident and faculty was required to sustain engagement with the program. Nonsurgical specialties contributed significantly to resident assessments (496, 28.8%).

Conclusion:

EPAs are being successfully integrated into the assessment framework at our institution. EPA implementation in surgery residency is a long-term process that requires investment, but may address limitations in the current assessment framework.

Keywords: Education, Assessment, Surgery Residency, Entrustable Professional Activities, Implementation

Introduction

The field of surgery is evolving much more quickly than the methods used to educate and evaluate surgery residents. Multiple stakeholder groups, including faculty surgeons, residency and fellowship program directors, and even residents themselves, have expressed concerns about the ability of the current surgical education system to prepare residents for unsupervised practice.1–7 The reasons the traditional training model may no longer be effective include advances in novel surgical techniques, the rapidly expanding surgical literature, limited resident interactions with any single faculty member, increasing subspecialization, financial pressures, administrative responsibilities competing with education, duty hour restrictions, and mandated increased supervision of surgical trainees.2,4–6,8 While some of these reasons are specific to the surgical fields, graduate medical education as a whole is attempting to adapt to medicine as practiced in the 21st century.

In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) endorsed the six Core Competencies to begin the transition to competency-based medical education (CBME).9 Competency-based education is learner-centered, and progression through the system is determined by mastery of specific knowledge and skills in contrast with more traditional education systems in which progression is determined by time in the system.9 The Core Competencies were an important first step, but difficulties with implementation lead to further changes. In 2009, Milestones were created within the Next Accreditation System.9 Milestones are narrative descriptions of competencies that track a resident’s development over time in relation to core aspects of surgical practice. While Milestones have provided more granularity for assessing resident performance, they are unable to capture the full scope of skills that a resident should be able to demonstrate at the end of training and are typically used to provide broad, infrequent, summative assessment. Additionally, the Milestones track progression of resident skills, knowledge, and abilities over the entire spectrum of surgery and do not necessarily demonstrate competence with respect to specific disease processes.

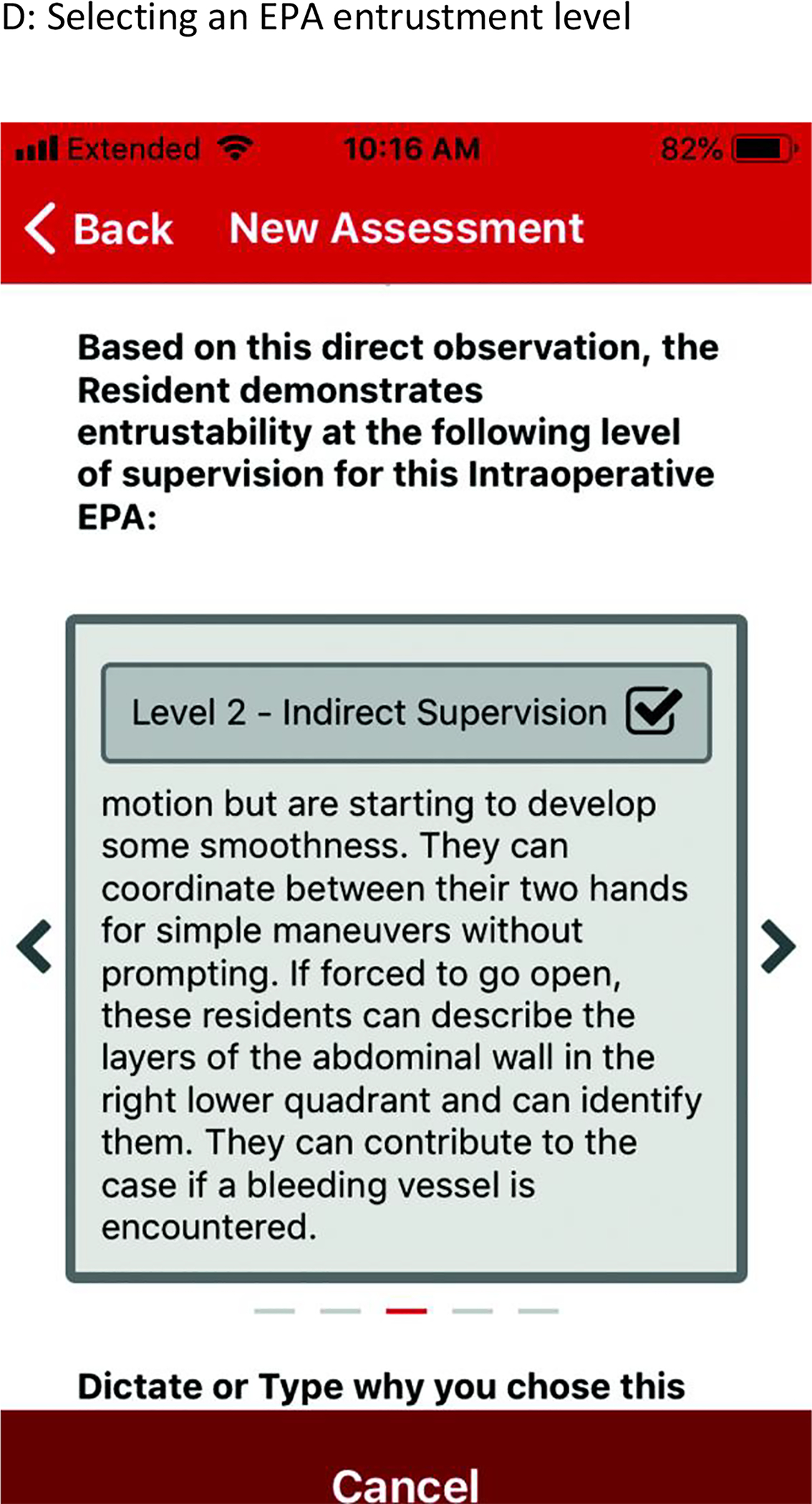

Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) are a novel technique used to operationalize the Competencies and Milestones.10,11 EPAs take a specific clinical activity (e.g. “provide general surgical consultation to other health care providers”12) and provide an entrustability roadmap ranging from zero to four (observation only, performance under direct supervision, performance under indirect supervision, independent practice, supervising others). Each level of entrustability is associated with a description of the behaviors exhibited by residents demonstrating that level of autonomy so that residents and faculty members can utilize a shared mental model of the entrustment behaviors at each level. Clinical care is represented by the integration of the competencies and their milestones; in caring for a patient, clinicians utilize medical knowledge, communication skills, technical skills, etc. However, Milestones address each of these in isolation, leading to feedback and a picture of ability that is fractured and not representative of a trainee’s actual capabilities. In contrast, EPAs combine the competencies and apply them to clinical situations in aggregate, rather than in isolation. EPA assessments are practical, performed in real-time and closely tied to discrete behaviors. This is a natural assessment for faculty to perform, and brings CBME back to its fundamental purpose: to create a surgeon workforce capable of providing excellent care to patients.

While the global process behind the construction of EPAs for a given field and the implementation across entire medical fields has been written about extensively13–18, there is relatively little written about how a given program can take a developed EPA framework and implement it into their residency.19–22 This manuscript describes the implementation of the five current EPAs in general surgery into a residency training program at an academic medical center.

Methods

The American Board of Surgery (ABS) developed five EPAs in general surgery (see Table 1) and recruited 28 residency programs to participate in a national pilot trial. This implementation study took place at an academic tertiary care center with a medium-sized general surgery residency program (7 residents per year). The implementation began with buy-in from the General Surgery Residency Program Director (JG) and Chair of the Department of Surgery (RM). Additional support for the project came from the surgical education research team within the department, including an education research scientist (SJ), associate research specialist (AR), and education fellow (CS). The department also employs several Information Technology personnel with experience in mobile platform application (app) development. The EPA group at our institution was strongly supported by the input from the national ABS EPA Pilot group at meetings held at the American College of Surgeons and Surgical Education Week conferences, as well as monthly webinars and conference calls in which participating members worked through the regulatory process and fundamentals of implementation together.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Submitted EPA Assessments

| Entrustable Professional Activities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Microassessments | N (%) | |

| Total | 1720 (100%) | |

| Submitted by | ||

| Resident | 898 (52.2%) | |

| Faculty | 822 (47.8%) | |

| Matched pairs | 569 (66.0%) | |

| EPA Type | ||

| Gallbladder Disease | 406 (23.6%) | |

| RLQ Pain | 303 (17.6%) | |

| Inguinal Hernia | 273 (15.8%) | |

| Trauma | 460 (26.7%) | |

| Consult | 278 (16.1%) | |

| Phase of Care | ||

| Intraoperative | 737 (42.8%) | |

| Nonoperative* | 983 (57.2%) | |

| Assessor Department | ||

| Surgery | 1224 (71.2%) | |

| EM | 496 (28.8%) | |

| Resident Department | ||

| Surgery | 1662 (96.6%) | |

| EM | 58 (3.4%) | |

| PGY status† | ||

| PGY1 | 196 (11.4%) | |

| PGY2 | 288 (16.7%) | |

| PGY3 | 450 (26.2%) | |

| PGY4 | 415 (24.1%) | |

| PGY5 | 274 (15.9%) | |

| Nonsurgical | 97 (5.6%) | |

includes preoperative, postoperative, consultative, and trauma care

for 2018–2019 year

Mobile Application Development

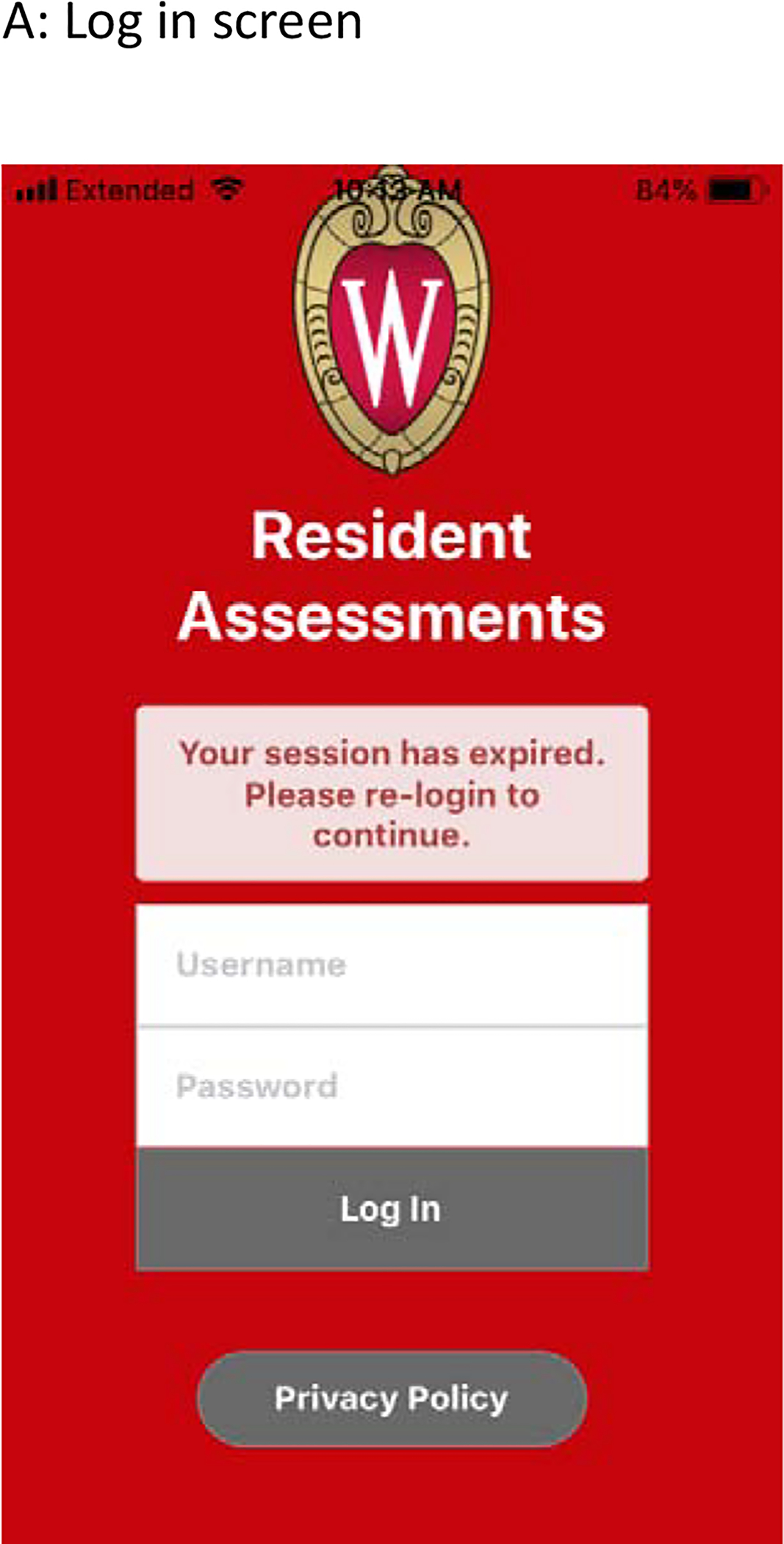

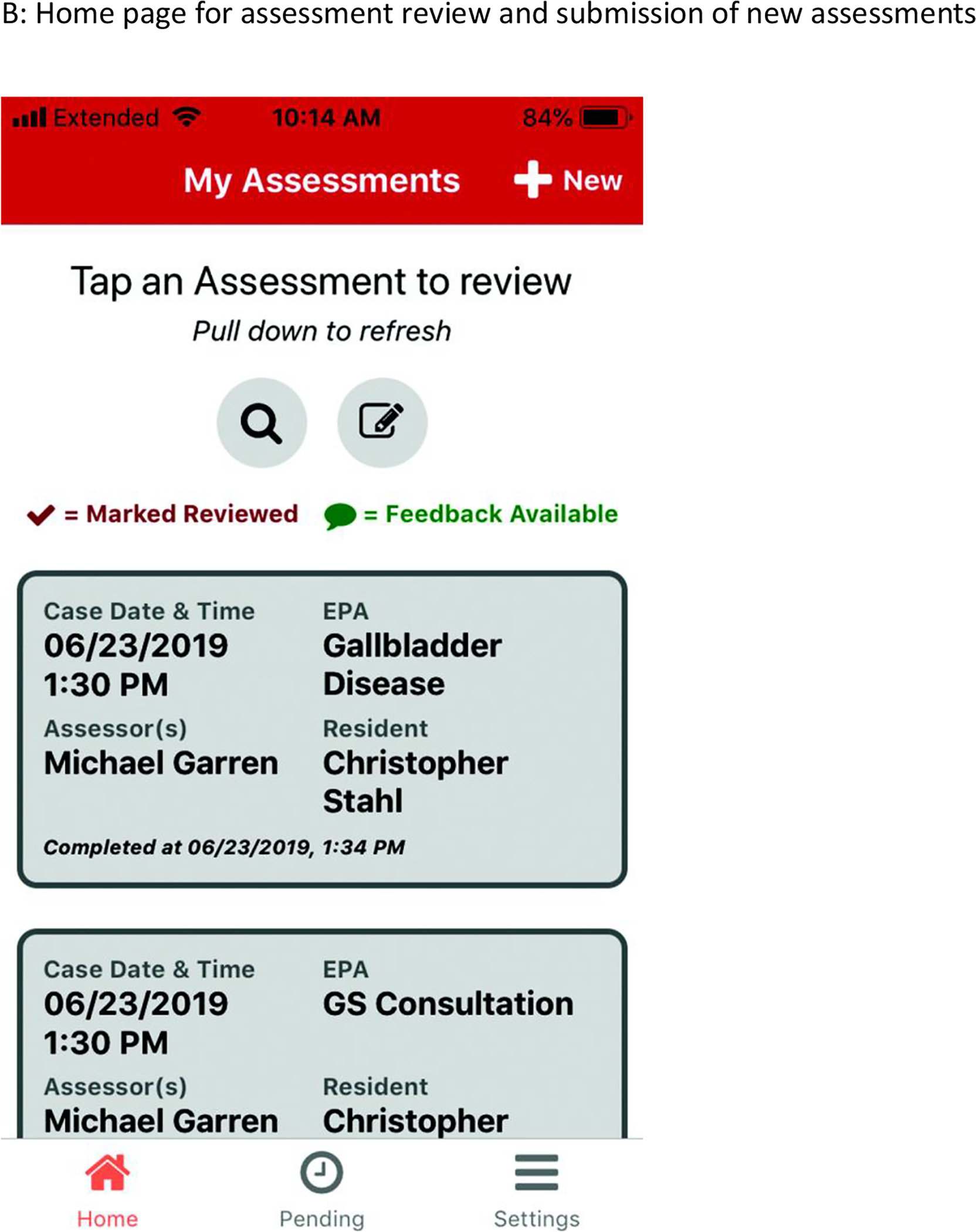

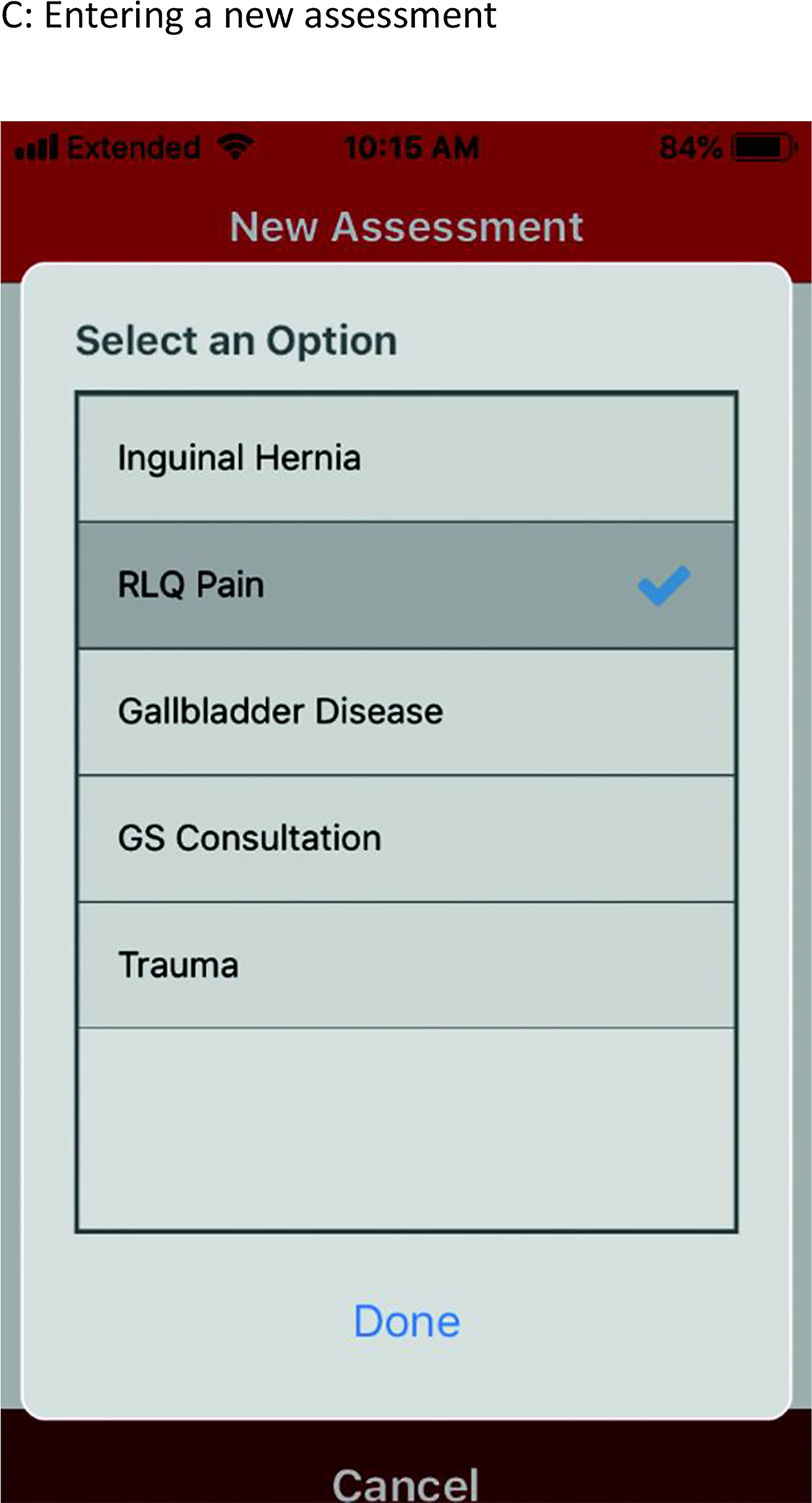

The five general surgery EPAs created by the ABS were used to create our mobile app. The app was designed and iteratively improved to facilitate rapid submission of entrustment levels (0–4) in a way that would be minimally disruptive to workflow for both faculty and trainees. The app was provided to residents in both general surgery and emergency medicine as both sets of trainees are involved in the care of traumatically injured patients at our institution. Additionally, faculty members in the Department of Surgery, the Department of Emergency Medicine, and the Division of Hospital Medicine were also given access to the app so that they could evaluate general surgery trainees on two of the five EPAs (trauma and consultative services).

After an EPA and observing faculty member is selected, the text description of each level of entrustment is shown along with the rating tool to allow easy review of behaviors expected at that level at the time of submission (Figure 1). Once an entrustment level is selected, a textbox allows for specific comments on that case. Text can be submitted by dictation or keypad. Initial submission can be performed by either the participating resident or faculty member. Once submitted, a push notification is sent to the matched resident or faculty member prompting them to submit an evaluation as well. To facilitate assessment by multiple faculty that may have input on a case (e.g. both the trauma surgeon and emergency medicine physician in the case of a trauma evaluation), residents can select multiple faculty. When faculty respond to a resident evaluation, the resident receives a notification that they have an unread assessment to review. Submitted evaluations can be searched by case date, time, EPA, assessor, resident, and completion time for easier review. On the back end, each submission is given a unique case ID to allow for further analysis and the data are fed into a secure website hosted on Department of Surgery servers. The data can be downloaded in aggregate and reports generated for clinical competency committee meetings, for distribution to individual residents, and for faculty members to review when a resident switches onto their service.

Figure 1:

Representative Screenshots of the EPA Mobile App

Throughout the implementation process, feedback on the app has been sought from multiple sources. The mobile app was designed to allow for feedback submission by end-users at any time. Additional feedback was solicited in-person periodically at educational conferences, and several of the driving members behind the EPA pilot use the app on a daily basis and contributed their personal experiences. One year after the implementation of EPAs, a formal web-based survey was developed (Qualtrics International Inc., Provo, Utah, United States) and distributed to residents and faculty to further guide innovation within the system. These surveys were 14 and 12 items long, respectively, with a mix of quantitative and qualitative questions covering constructs including: ease of use of the EPA app, integration of the EPA process into the current workflow, the utility of EPA feedback, barriers to EPA implementation and ways to improve, and resident autonomy. These surveys are available as supplemental material for review. Of note, these surveys were strictly designed for quality improvement purposes and are discussed in the manuscript only to highlight how they functioned as a tool assisting the iterative process of EPA implementation.

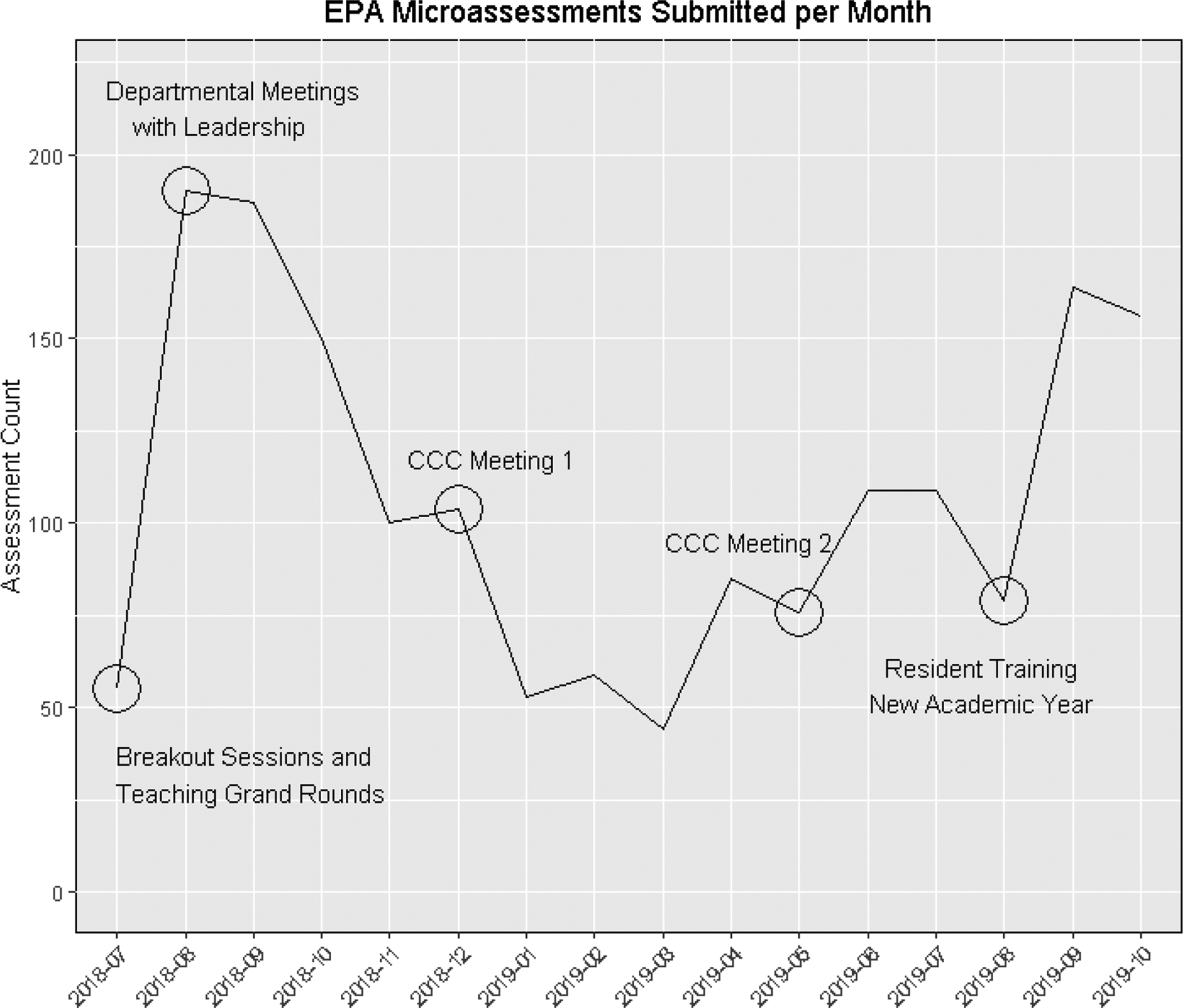

Faculty and Resident Development

Surgical residents were first exposed to the concept of EPAs, entrustment, and entrustability at our departmental annual education retreat and grand rounds in June 2018. Following this introduction, the first in-depth training occurred during an educational conference for general surgery residents in July 2018. The workshop was performed with jigsaw breakout groups designed to contain residents from each post-graduate year, and each group was given an example case and in-depth descriptors of resident behaviors that mapped to each entrustment level (0–4) for a specific EPA. Each group was assigned responsibility for one entrustment level for that EPA. Once group members understood the behavioral descriptors for that EPA entrustment level, the residents were reorganized into different groups containing at least one member of each original group. Each individual resident then taught the new group about the behaviors at each level of entrustment as they had learned in their initial group. This session was repeated a week later at a teaching grand rounds that was attended by both residents and participating surgery and emergency medicine faculty members. This provided a review for residents and utilized their experience to help teach participating faculty. Since the initiation of the EPA assessments, monthly emails have been sent out to participating residents and faculty, publically reporting number of evaluations submitted by residents and faculty members and recognizing high performers. There was a repeat training session in August of the new academic year.

Multi-Disciplinary Engagement

The General Surgery Residency Program Director met with leadership from the Department of Emergency Medicine and the Division of Hospital Medicine in order to incorporate them in our implementation and evaluation process. These two groups were specifically targeted to help assess general surgery residents in the Trauma and Consultative Services EPAs as these faculty members routinely observe general surgery residents performing different aspects of these clinical activities than surgery faculty, and add new perspective and breadth to the assessment process. Members of the research team and the General Surgery Residency Program Director attended faculty meetings in both Emergency Medicine and Hospital Medicine in order to introduce both EPAs as well as the mobile app in June of 2018.

Emergency Medicine (EM) approached the implementation of Trauma and Consultative Services EPAs as a new operational initiative, devoting specific attention to messaging and logistics to ensure a successful rollout. Initially, EM leadership outlined the importance of this project at its outset, ensuring that faculty were aware of the level of executive sponsorship from both Surgery and EM. Clear expectations were set for EPA assessment completion, with a goal of one completed assessment per EM faculty shift. Assessment completion was tracked for individual faculty members, and directly tied to faculty at-risk compensation. The EM faculty compensation model at our institution involves a pool of ‘at-risk’ pay that may be earned by fulfilling a number of different requirements aligned with the missions of the Department of EM. While most requirements to earn this compensation remain static from year-to-year (e.g. conference attendance, scholarly work), the Chair of EM selects new requirements annually. As the EPA project was a high priority collaboration between the Departments of Emergency Medicine and Surgery designed to improve interdisciplinary relationships among faculty and trainees within our trauma program, the Department of EM elected to designate the completion of 1 EPA assessment per shift as an option to qualify for the at-risk compensation pool. During the period of implementation, EPA assessment completion numbers were reviewed at monthly faculty meetings, at which time the Chair of EM reinforced the importance of continued vigilance in the implementation effort. These meetings also served to “gamify” the project for faculty by comparing response rates between Surgery and EM, as well as among EM faculty to promote friendly competition.

EPA assessment forms were offered to EM faculty in multiple formats to minimize the burden of completion. Faculty were all encouraged to use a smartphone application to complete assessments. For those who preferred to forgo the application, paper copies of the assessment forms were placed at the physician workstations in the ED. EM leadership met with surgery leadership on a bimonthly basis to review assessment completion rates and troubleshoot data collection issues. These meetings were attended by the surgery program director, the EM program director and associate program director, the EM Vice Chair of Education, and the surgical education research team.

Entrustment Decisions and the Clinical Competency Committee

Data from faculty EPA microassessments were used in subsequent clinical competency committee (CCC) meetings to create entrustment decisions for each resident in each EPA. A system was developed in which the data were first presented in a blinded fashion to the committee, concealing the identity of both the resident being assessed and the assessor. Therefore, all entrustment decisions were based solely on the data from the microassessments. The resident identity was then revealed, and that previously decided upon entrustment level was used as an additional data point in the ensuing CCC discussion. Resident entrustment levels were then distributed via email to both residents and faculty to facilitate entrustment and supervision decisions in clinical practice.

Data visualization was performed using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). This project was reviewed by the institutional Health Sciences IRB and certified as exempt from formal review (Application 2018–0451).

Results

From July 2018 to October 2019, 1,720 total microassessments were submitted at our institution. Approximately half of the assessments (n=898) were submitted by residents (52.2%), 983 were nonoperative (57.2%), and 1,224 involved assessors from the Department of Surgery (71.2%). The most common EPAs evaluated were Trauma evaluations, followed by Gallbladder Disease, Consults, Inguinal Hernia, and Right Lower Quadrant Pain (Table 1). The majority of assessments were matched pairs (66.0%), meaning both resident and faculty submitted an assessment for the same case/consult. Assessment by non-surgical faculty, primarily in the Department of Emergency Medicine, was common, at 28.8% of all microassessments.

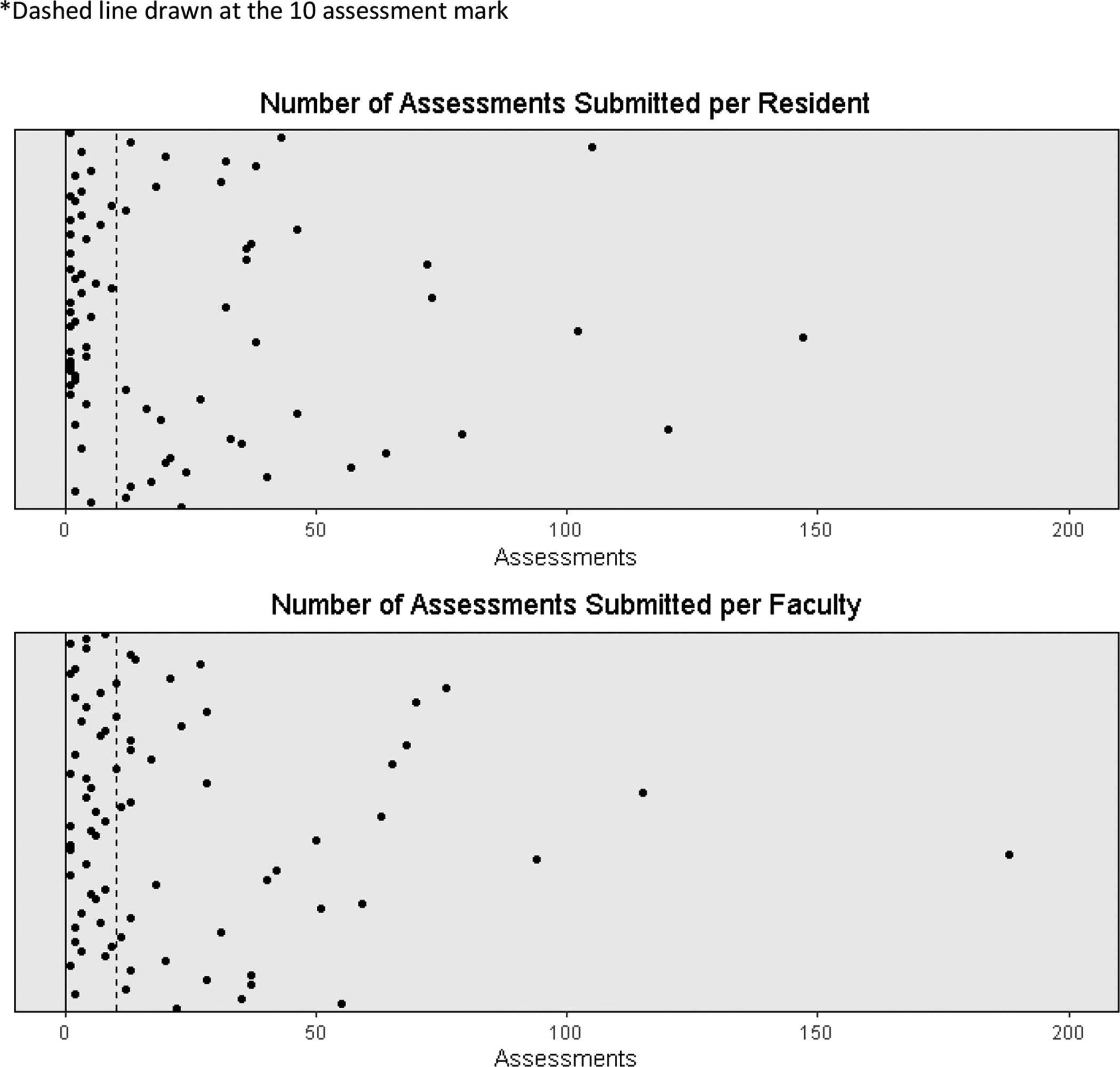

There was significant variation in microassessment counts at the individual resident and faculty level. Several “early adopters” were present in each group that were significant outliers relative to their peers, but overall penetrance was limited (Figure 2). Of residents and faculty with at least one EPA assessment, the median number of assessments were 9 and 10, respectively. The number of EPA assessments submitted per month varied, with notable increases in submissions following dedicated resident and faculty development sessions (Figure 3).

Figure 2:

Variation in Resident and Faculty Assessments*

Figure 3:

Monthly Variation in Total EPA Assessment Submissions

The mobile EPA application collects both entrustment level as well as text feedback for each assessment. The vast majority of assessments (99.9%) contained text feedback (>=2 words entered into the text box), with a median word count of 23 (mean 30.5). After removal of stop words (common words with very little meaning such as “the” or “and”, and any words under 3 letters in length), the top 200 words submitted as part of an EPA microassessments are demonstrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4:

200 Most Common Words Present in EPA Text Feedback

A survey submitted to general surgery residents, Surgery faculty, and EM faculty demonstrated that while the app is easy to use, there are still multiple barriers to assessment submission (Table 2). The most common barriers for residents were forgetting to submit the EPA in the moment after their case/consult and the initial low faculty response rate after residents sent an evaluation. Interestingly, the most common barrier reported for faculty was residents not sending them enough EPA assessment requests. Some suggested improvements from the survey included a daily notification in the evening prompting submission of any EPA eligible cases from the previous day and repeat training on how to use the application with examples from those who had implemented the process well in their daily practice.

Table 2:

Five Most Common Barriers to EPA Assessment Submission for Residents and Faculty

| Faculty Survey (n=28) | Response | Count (%)* |

|---|---|---|

| Residents do not send me EPAs | 19 (34%) | |

| Other | 9 (16%) | |

| I find it difficult to develop a habit when EPAs only exist for certain operations | 8 (14%) | |

| I don’t have time | 7 (13%) | |

| I intend to submit EPAs, but forget after being notified | 6 (11%) | |

| Resident Survey (n=16) | ||

| I intend to submit EPAs, but forget in the moment | 10 (29%) | |

| The low faculty response rate | 7 (21%) | |

| It is difficult for me to develop a habit when EPAs are only used on certain rotations | 7 (21%) | |

| I don’t have time | 3 (9%) | |

| I don’t find them useful and choose not to submit them | 3 (9%) |

respondents could select more than one response

Discussion

Implementation of EPA assessments into a busy general surgery residency program is possible, but has challenges. Given the time-intensive and difficult nature of surgical training, any change in assessment model that requires buy-in and time from a diverse group of residents and faculty is difficult to implement. Programs should expect an ongoing process of implementation, with repeated training sessions for both residents and faculty, and iterative improvements in methods of feedback collection over time. Even with the success seen at our program, the number of EPAs submitted per resident and faculty member is highly variable (Figure 2), with a small number of high outliers and many resident with low numbers of microassessments. This is in part related to only having 5 EPAs currently developed and thus exposure and opportunity to a possible EPA assessment varies significantly depending on the resident rotations. However, results from an internal survey also highlighted that both the resident and faculty groups attribute lack of participation by the other group as major barrier to their submission of additional microassessments. Other barriers included lack of time to submit evaluations, lack of training, difficulty implementing EPAs into their workflow as they only exist for a small number of surgeries/conditions, and simply forgetting submissions during the busy clinical day.

Despite these challenges, a high volume of EPA assessments were collected at our program in the first year of the pilot. Aspects of the implementation that were key to this success included high-level departmental buy-in and allocation of personnel critical for both application development and behavior change throughout the department. A focus on streamlining the assessment process using a mobile application and incorporating all available EPAs were strategies that minimized barriers to EPA assessment submission and helped make a novel assessment practice routine. The incorporation of resident self-assessment into the EPA process facilitated resident buy-in to the process, and helped drive faculty engagement when they received notifications with resident requests for feedback. The overarching theme guiding this work was to design EPAs in such a way as to provide value to both faculty and trainees that need to invest their precious time and expertise in order to make the process function.

The literature discussing practical aspects of EPA implementation into residency programs is limited, but generally supports our findings. Key lessons learned in the implementation of a competency-based EPA curriculum at Oregon Health and Science University include: choose leaders wisely, don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good, expect resistance, and emphasize the importance of effective communication.20 A manuscript discussing the implementation of CBME using EPAs into a family medicine residency in Canada highlights the high resource requirements a shift to CBME takes in terms of both personnel-hours and an estimated 600 hours for software development.21 They also highlight the importance of departmental buy-in, local champions within the program, resident/faculty development, removing obstacles, creating short term wins, and note that they wish they had further developed residents’ self-assessment and feedback-seeking skills earlier during the process. An article discussing tips for the operationalization of EPAs highlighted the need for encouraging learner ownership and engagement in the assessment process, using technology to facilitate documentation, and the use of aggregate metrics for program evaluation.22 Finally, an article from the Netherlands about using EPAs to develop a physician assistant curriculum describes the three pillars of implementation as 1) a central developmental portfolio for each learner that aggregates assessments, 2) statements of awarded responsibility after competency has been attained, and 3) supervisor training.19 Themes regarding the importance of effective leadership, rapid development and implementation of curricular improvements, effective communication, buy-in and local champions, repeated resident and faculty training, and leveraging technology to simplify the process seem to be cross-cutting through experiences in multiple settings.

We are planning future interventions at our program based on these overarching principles. Faculty and resident development sessions at the start of each academic year will review the purpose of EPA microassessments and describe how they are utilized by the program. Best practices from high outliers in the program will be identified and disseminated. The app itself will continue to be iteratively developed, in particular by creating an automated daily reminder that will help develop habits. We will continue to streamline the application to make assessment as rapid and simple as possible. Monthly emails recognizing high performers and publically reporting numbers of submitted EPAs will continue to both recognize success and provide peer pressure/competitive drive to participants. CCC meetings will continue to incorporate EPA data and disseminate those summative findings to individual residents and faculty when residents rotate onto their specialty services. Residents and faculty will be given access to an “EPA Portal” where they can create their own reports showing their own EPA data in a summative fashion in addition to piecemeal through the mobile app. Ultimately, we recognize that the change to an EPA-based assessment framework, while representing an important and overdue focus on competency and autonomy in surgical education, is an additional burden on already overworked residents and faculty members. We have tried to view EPA assessment application as a product that we are creating for end-users, iteratively improving usability, utility, and the use of the data in a way that benefits all involved. We recognize that true EPA adoption into a program will require EPAs to add tangible value to the end-users who are asked to frequently contribute their time and expertise.

Despite being one of the first papers to look at implementation of EPAs into a general surgery training program, this study has several limitations. Our implementation strategy may not be generalizable to all general surgery programs. A combination of high-level institutional buy-in, dedicated departmental resources, and excellent relationships with co-existing hospital departments facilitated our success and may not be available to every program. However, we hope that programs may look at our experience in total and select aspects of the process that can be adapted to their specific circumstance. Additionally, some resource-intensive aspects of the process (e.g. app creation and development) can be collaboratively distributed from resource-rich programs or governing societies to programs with limited resources to facilitate dissemination/implementation on a national scale. The ABS EPA Pilot group has experience implementing EPAs into a wide variety of programs and is willing to share their experiences with programs that are trying to develop their own system. Of course, any single surgical residency is a limited sample size, and our experience should be compared with those at other institutions to assess generalizability.

Conclusions

Entrustable Professional Activities are being successfully implemented into the surgery resident assessment framework at our institution. This model can be used to assist other programs hoping to develop a similar assessment program. EPAs are an important step on the journey towards competency-based assessment in surgery, and provide timely, activity-specific, focused feedback to surgery residents to support their progression towards full entrustment and autonomous practice. Successful EPA implementation is a long-term process that requires departmental buy-in and significant resident and faculty development.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Entrustable Professional Activities can be implemented into surgery residency

Effective implementation requires leveraging technology

Repeat exposure is required for effective engagement

Entrustable Professional Activities may address current assessment limitations

Grant Support:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers T32CA090217. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- EPA

Entrustable Professional Activity

- CBME

Competency-Based Medical Education

- EM

Emergency Medicine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Meeting Presentation: This work was presented at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2019, San Francisco, CA, October 2019

References

- 1.Coleman JJ, Esposito TJ, Rozycki GS, Feliciano DV. Early subspecialization and perceived competence in surgical training: are residents ready? J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(4):764–771; discussion 771–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenna DT, Mattar SG. What Is Wrong with the Training of General Surgery? Advances in Surgery. 2014;48(1):201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattar SG, Alseidi AA, Jones DB, et al. General surgery residency inadequately prepares trainees for fellowship: results of a survey of fellowship program directors. Ann Surg. 2013;258(3):440–449. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a191ca [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Napolitano LM, Savarise M, Paramo JC, et al. Are general surgery residents ready to practice? A survey of the American College of Surgeons Board of Governors and Young Fellows Association. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(5):1063–1072.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiSegna ST, Kelley TD, DeMarco DM, Patel AR. Effects of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Duty Hour Regulations on Clinical Preparedness of First-Year Orthopaedic Attendings: A Survey of Senior Orthopaedic Surgeons. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2018;27(1):42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klingensmith ME, Lewis FR. General surgery residency training issues. Adv Surg. 2013;47:251–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonseca AL, Reddy V, Longo WE, Gusberg RJ. Graduating general surgery resident operative confidence: perspective from a national survey. J Surg Res. 2014;190(2):419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandhu G, Teman NR, Minter RM. Training Autonomous Surgeons: More Time or Faculty Development? Annals of Surgery. 2015;261(5):843–845. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milestones Resources. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Milestones/Resources. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- 10.ten Cate O Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Medical Education. 2005;39(12):1176–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ten Cate O, Hart D, Ankel F, et al. Entrustment Decision Making in Clinical Training. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):191–198. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stucke RS, Sorensen M, Rosser A, Sullivan S. The surgical consult entrustable professional activity (EPA): Defining competence as a basis for evaluation. Am J Surg. December 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.12.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carraccio C, Englander R, Gilhooly J, et al. Building a Framework of Entrustable Professional Activities, Supported by Competencies and Milestones, to Bridge the Educational Continuum. Academic Medicine. 2017;92(3):324. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brasel KJ, Klingensmith ME, Englander R, et al. Entrustable Professional Activities in General Surgery: Development and Implementation. Journal of Surgical Education. 2019;76(5):1174–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shorey S, Lau TC, Lau ST, Ang E. Entrustable professional activities in health care education: a scoping review. Medical Education. 2019;53(8):766–777. doi: 10.1111/medu.13879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkins RE, Welcher CM, Holmboe ES, et al. Implementation of competency-based medical education: are we addressing the concerns and challenges? Medical Education. 2015;49(11):1086–1102. doi: 10.1111/medu.12831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lomis K, Amiel J, Ryan M, et al. Implementing an Entrustable Professional Activities Framework in Undergraduate Medical Education: Early Lessons From the AAMC Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency Pilot. Academic Medicine. 2017;92(6):765–770. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ten Cate O, Scheele F. Viewpoint: Competency-Based Postgraduate Training: Can We Bridge the Gap between Theory and Clinical Practice? Academic Medicine. 2007;82(6):542–547. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31805559c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulder H, Cate OT, Daalder R, Berkvens J. Building a competency-based workplace curriculum around entrustable professional activities: The case of physician assistant training. Medical Teacher. 2010;32(10):e453–e459. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.513719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mejicano G, Bumsted T. Describing the Journey and Lessons Learned Implementing a Competency-Based, Time-Variable Undergraduate Medical Education Curriculum. Academic Medicine. 2018;93(3S). doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schultz K, Griffiths J. Implementing Competency-Based Medical Education in a Postgraduate Family Medicine Residency Training Program: A Stepwise Approach, Facilitating Factors, and Processes or Steps That Would Have Been Helpful. Academic Medicine. 2016;91(5):685–689. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters H, Holzhausen Y, Boscardin C, ten Cate O, Chen HC. Twelve tips for the implementation of EPAs for assessment and entrustment decisions. Medical Teacher. 2017;39(8):802–807. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1331031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.