Summary

Escherichia coli broadly colonize the intestinal tract of humans and produce a variety of small molecule signals. However, many of these small molecules remain unknown. Here, we describe a family of widely distributed bacterial metabolites termed the “indolokines.” In E. coli, the indolokines are upregulated in response to a redox stressor via aspC and tyrB transaminases. While indolokine 1 represents a previously unreported metabolite, four of the indolokines (2-5) were previously shown to be derived from indole-3-carbonyl nitrile (ICN) in the plant pathogen defense response. We show that the indolokines are produced in a convergent evolutionary manner relative to plants, enhance E. coli persister cell formation, outperform ICN protection in an Arabidopsis thaliana-Pseudomonas syringae infection model, trigger a hallmark plant innate immune response, and activate distinct immunological responses in primary human tissues. Our molecular studies link a family of cellular stress-induced metabolites to defensive responses across bacteria, plants, and humans.

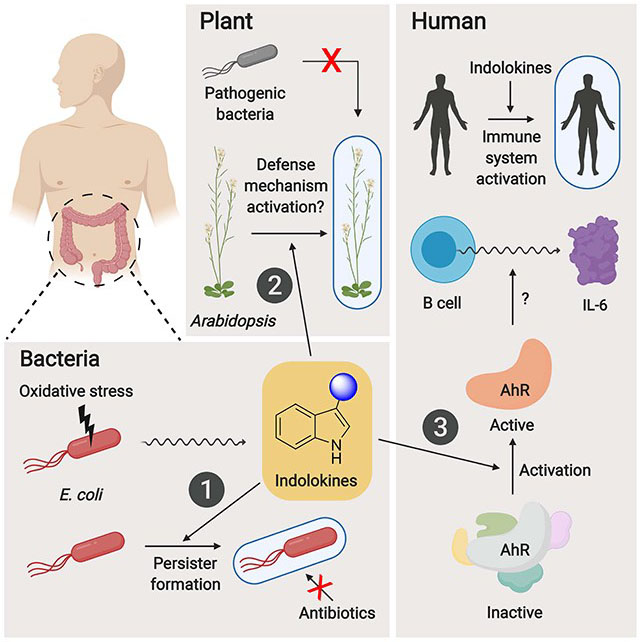

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Kim, Li, et al. describe the characterization of cellular stress-induced, bacterial indole-functionalized metabolites termed “indolokines.” The indolokines are found in diverse bacteria, enhance persister formation in E. coli, and activate innate immune responses in both plant and human tissues.

Introduction

The human intestinal tract contains a diverse microbial community known as the gut microbiota that includes trillions of microbial cells. The gut microbiota members produce tens of thousands of detectable metabolites, but the majority of these putative small molecules remain structurally and functionally uncharacterized (Donia and Fischbach, 2015; Dorrestein et al., 2014; Rath and Dorrestein, 2012). Escherichia coli is one of the most well-studied gut bacteria estimated to reside in ~90% of the human population (Secher et al., 2016). E. coli isolates serve as commensals (Tenaillon et al., 2010), probiotics (Sonnenborn, 2016), and pathogens with the latter contributing to well over 200 thousand infections per year in the United States alone (Scallan et al., 2011). To mediate their diverse interactions with other microbes and their animal host, E. coli strains produce diverse small molecule metabolites to mediate bacterial signaling [e.g., indole (Kumar and Sperandio, 2019; Lee et al., 2015), autoinducer-2 (Papenfort and Bassler, 2016), and autoinducer-3 (Kim et al., 2019; Sperandio et al., 2003)], inter-microbial competition [e.g., microcins (Asensio et al., 1976)], iron acquisition [e.g., enterobactin, enterochelin, salmochelin, aerobactin, and yersiniabactin (Ellermann and Arthur, 2017)], and host physiological responses [e.g., colibactin (Nougayrède et al., 2006; Xue et al., 2019)], among others. Biosynthesis of these representative small molecules range from simple modifications of primary amino acid precursors to highly complex multi-modular nonribosomal peptide synthetase and polyketide synthase systems.

AspC is a pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent amino acid transaminase that reversibly converts amino acids (l-Phe, l-Trp, l-Tyr, l-Asp, l-kynurenine, and l-Cys) into their α-ketoacid forms using 2-oxoglutarate as a preferred co-substrate (Chatagner and Sauret-Ignazi, 1956; Gelfand and Steinberg, 1977; Han et al., 2001; Romasi and Lee, 2013). Intriguingly, genetic studies have linked aspC to a core “hormetic” antibiotic stress response, which operates through the general RpoS stress response regulon (Mathieu et al., 2016), and to the formation of bacterial persister cells, an antibiotic tolerant cell state (Shan et al., 2015). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these phenotypes remain unknown. In this study, we describe a new family of aspC-regulated signaling molecules in E. coli, which invoke the coupling of l-Trp- and l-Cys-derived metabolites, and explore their biological defense functions in bacteria, plants, and humans. Strikingly, the metabolites enhance bacterial persister cell formation and regulate innate immune responses in both plant and human tissues, expanding our understanding of the detailed molecular interactions possible at the host-microbe interface.

Results and Discussion

Detection of aspC/tyrB-dependent metabolites from diverse bacteria and mouse fecal samples

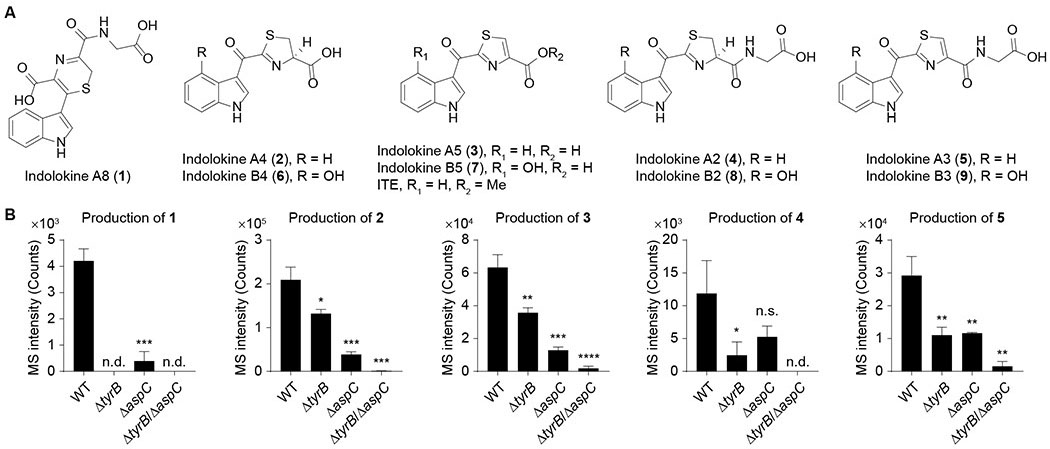

To identify new bacterial metabolites regulated by transaminase aspC, we conducted differential metabolite analysis between the commensal model E. coli BW25113 and its aspC mutant strain via liquid chromatography coupled to a photodiode array detector and an electrospray ionization-quadrupole time of flight-mass spectrometer (ESI-QTOF-MS). Because transaminase tyrB can also accept similar substrates as aspC, we also analyzed a tyrB mutant and an aspC-tyrB double mutant. Five metabolites with distinctive indole-like chromophores and protonated masses of m/z 360.0630 (1, C16H14N3O5S+, calc 360.0649), 275.0486 (2, C13H11N2O3S+, calc 275.0485), 273.0324 (3, C13H9N2O3S+, calc 273.0328), 332.0703 (4, C15H14N3O4S+, calc 332.0700), and 330.0538 (5, C15H12N3O4S+, calc 330.0543) were significantly down-regulated in the transaminase mutants relative to wild-type cells (Figure 1). These transaminase-regulated ions were not consistent with any metabolites previously reported from E. coli.

Figure 1. Structure of indolokine metabolites and characterization of their genetic origins in E. coli.

A, Structures of characterized bacterial metabolites (indolokines 1-5) and their plant-derived analogs (6-9). B, Comparison of metabolite production levels between wild-type E. coli BW25113 and its tyrB, aspC, and tyrB-aspC mutants. n = 3 biological replicates. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. n.s., not significant; n.d., not detected. Two-tailed t-test.

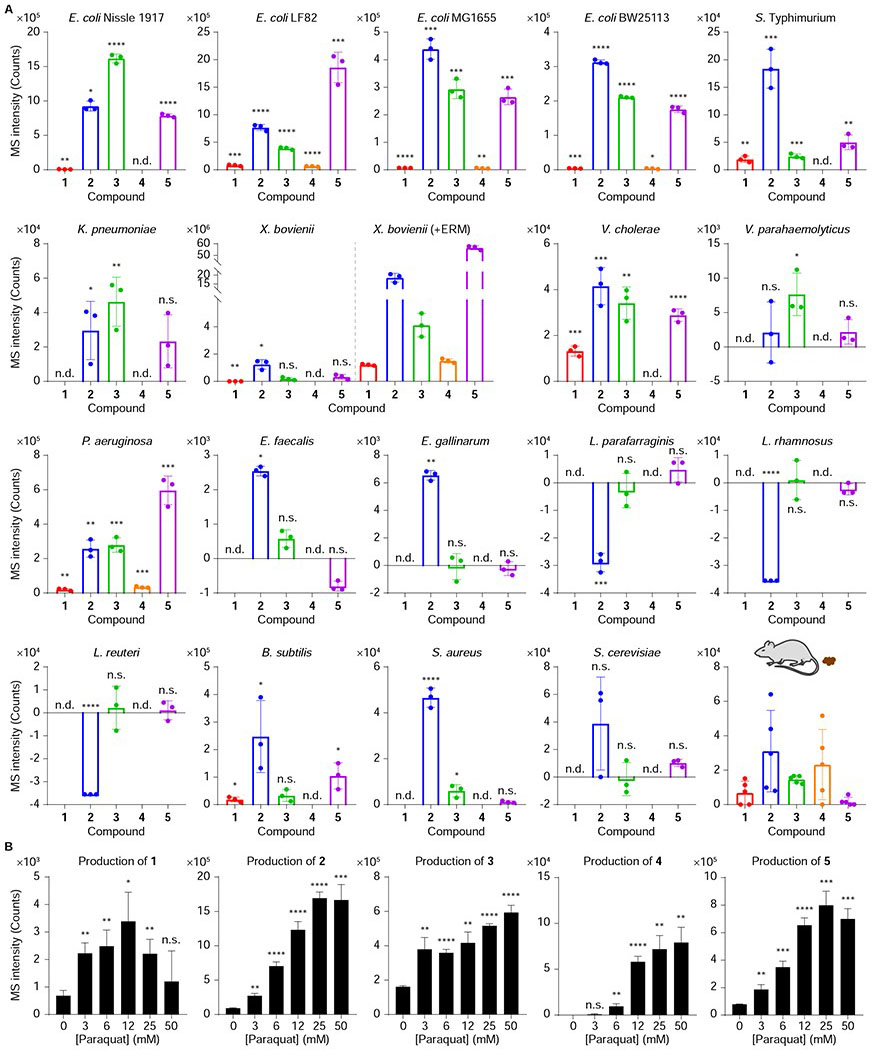

Because amino acid transamination reactions are broadly catalyzed by primary PLP-dependent enzymes (McMurry and Begley, 2016), we proposed that metabolites 1-5 could be detected in other bacteria. Thus, we first analyzed probiotic, pathogenic, and commensalistic E. coli strains, including E. coli Nissle 1917 associated with the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) (Schultz, 2008), adherent invasive E. coli (AIEC) LF82 associated with the severity of Crohn’s disease (Agus et al., 2014), and E. coli MG1655 / BW25113 as model commensal strains (Baba et al., 2006). The metabolites could be detected across all of the E. coli strains (Figure 2A), suggesting that the metabolites were general E. coli metabolites rather than being strain specific. We next analyzed other well-known Gram-negative [human pathogens Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603, Vibrio cholerae El Tor N16961 ΔctxAB, V. parahaemolyticus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, and entomopathogen Xenorhabdus bovienii str. feltiae Moldova] and Gram-positive bacteria [pathogens vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis (VRE), Enterococcus gallinarum (Manfredo Vieira et al., 2018), and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ATCC BAA-1717 (MRSA); commensals Lactobacillus parafarraginis F0439, Lactobacillus rhamnosus LMS2-1, and Lactobacillus reuteri CF48-3A; and environmental isolate Bacillus subtilis BR151], as well as a representative fungus, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Under our cultivation conditions, most of the bacteria produced some or all of the metabolites except for the three Lactobacillus species and S. cerevisiae (Figure 2A). Since metabolites 2, 3, and 5 were also detected at basal levels in media controls, statistically significant bacterial production levels of these three metabolites were obtained by comparing and subtracting respective media signals. Intriguingly, the significant negative values of metabolite 2 in the three Lactobacillus species likely derive from bacterial degradation of background metabolite. These studies suggest that 1-5 are commonly produced bacterial metabolites, initiating from aromatic amino acid transamination.

Figure 2. Production of indolokines 1-5 in various microbial strains and mouse fecal samples.

A, Production of indolokines 1-5 from E. coli Nissle 1917, E. coli LF82, E. coli MG1655, E. coli BW25113, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, X. bovienii str. feltiae Moldova (with and without 25 μM of erythromycin (ERM) as a ribosomal stressor), V. cholerae El Tor N16961 ΔctxAB, V. parahaemolyticus, P. aeruginosa PAO1, vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis (VRE), E. gallinarum, L. parafarraginis F0439, L. rhamnosus LMS2-1, L. reuteri CF48-3A, B. subtilis BR151, methicillin-resistant S. aureus ATCC BAA-1717 (MRSA), S. cerevisiae, and mouse fecal samples. n = 3 (bacteria) or 5 (mouse fecal samples) biological replicates. Data are presented by mean ± s.d. of MS intensities (counts) observed in bacterial culture extracts subtracted by the mean of the media background signals. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, n.s., not significant; n.d., not detected. Two-tailed t-test between bacterial metabolite production level signals and respective media control signals. B, Dose-dependent regulation of 1-5 in E. coli Nissle 1917 by paraquat. n = 3 biological replicates. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. n.s., not significant. Two-tailed t-test between no stress controls and paraquat stress conditions.

Given aspC’s phenotypic role in regulating stress responses (Mathieu et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2015), we treated E. coli Nissle 1917 with sub-lethal concentrations of the redox stressor paraquat as a mimetic of host immune stress. Paraquat causes oxidative cellular stress through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Bus and Gibson, 1984; Fukushima et al., 1994); ROS is produced by the gut epithelia when in contact with enteric bacteria (Jones et al., 2012). From these experiments, we observed the dose-dependent enhancement of metabolites 1-5 in E. coli (Figure 2B), suggesting that the metabolites may contribute to the AspC cellular stress response phenotypes in cell culture. We also examined whether the metabolites could be detected in the fecal samples of specific pathogen free C57BL/6 mice colonized with E. coli (Park et al., 2019). LC/MS analysis of the fecal samples showed good detection of all five metabolites (Figure 2A). Because we have shown that these bacterial metabolites are not limited to E. coli, multiple members of the gut microbiota likely contribute to the observed signals. Collectively, these studies indicate that metabolites 1-5 are regulated by transaminases AspC/TyrB in E. coli, upregulated in response to redox stress, found in diverse bacteria, and could be physiologically-relevant in vivo. These results prompted us to solve their unknown structures and evaluate their biological activities.

Structural characterization of indolokines.

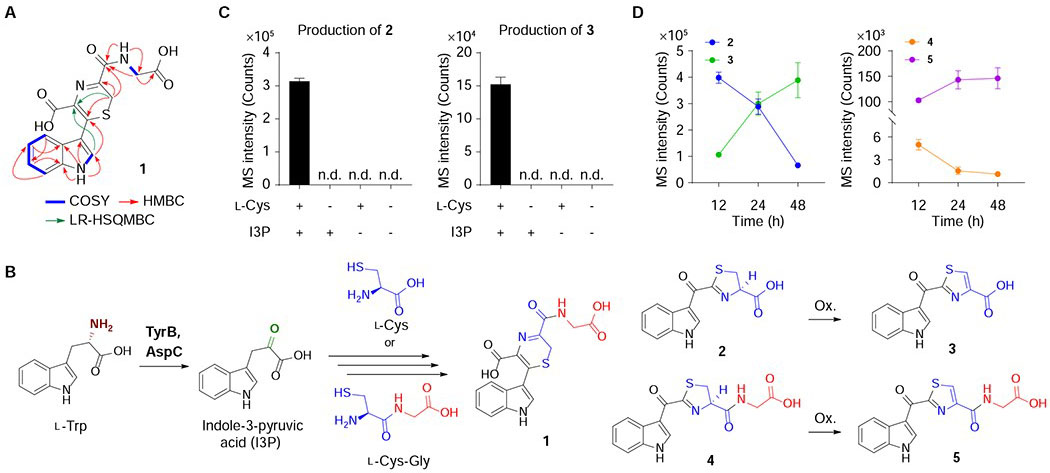

To characterize their chemical structures, we first cultured 4 L of X. bovienii as a representative producer. These cultures were treated with sub-lethal concentrations of erythromycin to induce ribosome stress, as this led to the robust production of these molecules to facilitate isolation (Figure 2A). Metabolites 1 and 5 were extracted into n-butanol, isolated via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and characterized using 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy (1H, 13C, COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and LR-HSQMBC) and tandem MS (Figures 3A, S1, and S2, Table S1). Key NMR correlations to establish novel molecule 1 are shown in Figure 3A. By comparing tandem MS spectra between the characterized bacterial-derived metabolite 5 and its variants 4 (+2, for +H2), 3 (−57, for −Gly+H2O), and 2 (−55, for −Gly+H2O+H2), we proposed their structures as reduced, deglycinated, and reduced-deglycinated derivatives of 5, respectively. To confirm this proposal, we synthesized 2-4 using established procedures (Rajniak et al., 2015) and demonstrated that they shared identical tandem MS spectra (Figure S2) and LC retention times (Figure S3) with those of the natural materials. While 1 is a previously unreported small molecule with an unusual 2H-1,4-thiazine ring, which was reported only once in natural products cytochathiazines A-C isolated from co-culture of Chaetomium globosum and Aspergillus flavipes (Wang et al., 2018), metabolites 2-5 and 3 were characterized from the plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Rajniak et al., 2015) and a thermophilic bacterium Thermosporothrix hazakensis SK20-1T (Park et al., 2015), respectively. Based on prior plant metabolite nomenclature (Rajniak et al., 2015) and other functions discussed below, we named these five metabolites indolokines A8 (1), A4 (2), A5 (3), A2 (4), and A3 (5).

Figure 3. Proposed biosynthesis of the indolokines.

A, Key NMR correlations for novel small molecule 1. COSY (blue bold); HMBC (red arrows); LR-HSQMBC (green arrows). B, Proposed pathway of 1-5 in E. coli. Ox., oxidation. C, Biomimetic synthesis of 2 and 3 in M9 medium (see Figure S3 for corroborating LB medium data). Metabolites 2 and 3 were produced only when both l-Cys and I3P were present. n = 3 biological replicates. Data are mean ± s.d.; n.d., not detected. D, Time-course analysis for production of metabolites 2-5 in E. coli Nissle 1917.

Biosynthetic proposal of indolokines

Given the structural variations observed in 1-5, we proposed that indole-3-pyruvic acid (I3P) derived from AspC- and TyrB-mediated transamination of l-Trp could spontaneously react with l-Cys or l-Cys-Gly dipeptide to produce the indolokines (Figure 3B). l-Cys-Gly dipeptide is a common metabolite in glutathione biosynthesis (Hanes et al., 1950; Meister and Tate, 1976). To test this proposal, we incubated I3P (1 mM) and l-Cys (1 mM) in the absence of bacteria under identical culture conditions (M9 medium, 37 °C, 48 hrs). As anticipated, compounds 2 and 3 were detected from these reaction mixtures and were abolished when either I3P or l-Cys were absent in the reaction mixtures (Figure 3C). These studies support a non-enzymatic coupling pathway, which is consistent with their broader detection in various bacteria. In E. coli cultures, production of the two reduced metabolites 2 and 4 decreased over 12-48 hours while production of their oxidized variants 3 and 5 inversely increased, which is consistent with our proposal (Figure 3D).

Persister-forming activity of indolokines in E. coli

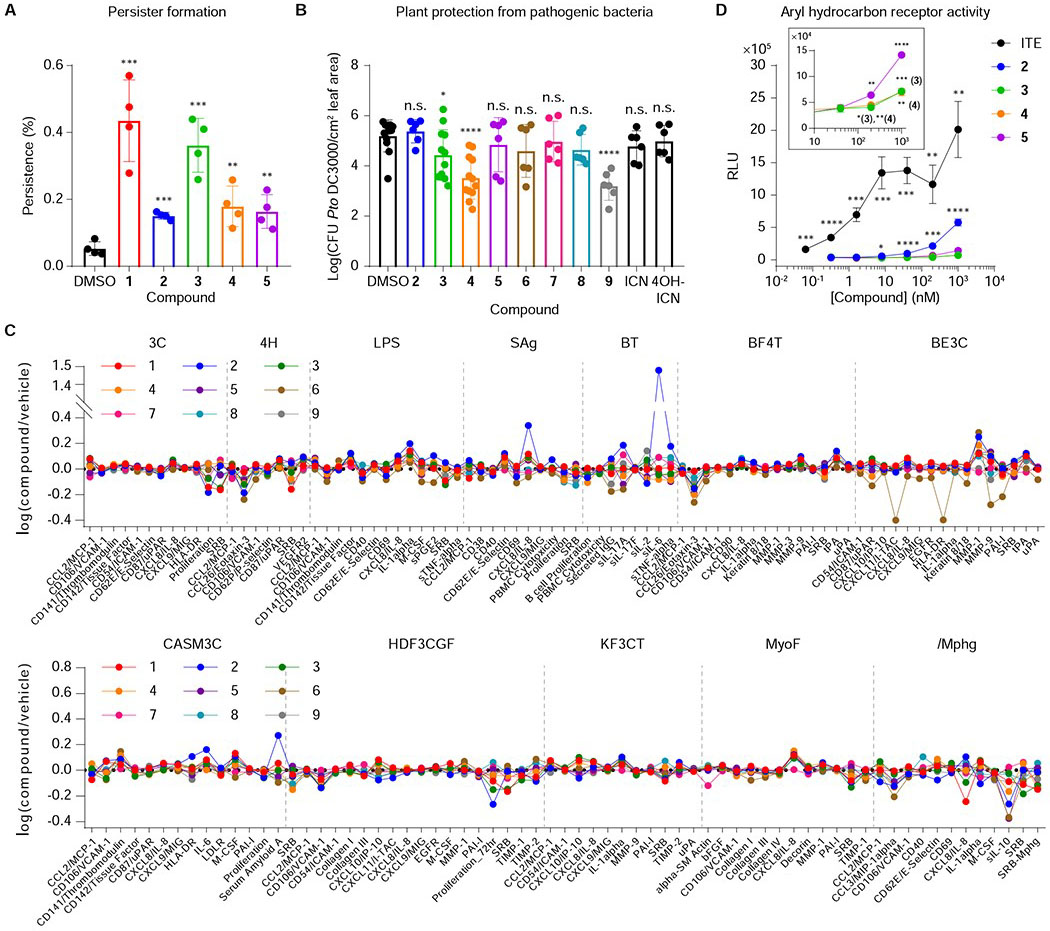

Indole and indole-functionalized metabolites are known to contribute to persister cell regulation in E. coli at high concentrations (sub-mM to mM) (Hu et al., 2015; Kwan et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Vega et al., 2012). Intriguingly, aspC also contributes to stationary phase regulation of persister cell formation in E. coli, and the addition of amino acids did not rescue this phenotype (Shan et al., 2015). We proposed that aspC-derived metabolites, such as the indolokines, could similarly contribute to this phenotype. To test this proposal, we first needed to establish physiologically-relevant doses. Using the standard addition method (Skoog et al., 2017), we determined the concentrations of oxidized 3 and 5 in aerobic stationary phase cultures to be ~0.2 μM and ~0.04 μM, respectively. However, under paraquat cellular stress conditions, their concentrations were upregulated by about one order of magnitude (Figure 2B). Consequently, we individually treated E. coli BW25113 with indolokines 1-5 at 5 μM to mimic a stressed cell environment in our persister cell assays. Assays were conducted under aerobic conditions, as in prior studies (Shah et al., 2006; Shan et al., 2015; Vega et al., 2012). We used gentamicin sulfate to challenge the cultures, as this aminoglycoside kills both growing and non-growing cells and has been used to eradicate non-persister cells (Shan et al., 2015). Under these conditions, we observed a reproducible and significant increase in colonies indicative of an increase in persister cell formation in stationary phase cultures (Figure 4A). Supplementation with compounds 1 and 3, for example, led to an ~10-fold enhancement (1, 12-fold; 3, 10-fold), which is consistent with the ~50-fold change previously observed between wildtype and aspC mutant cultures (Shan et al., 2015). In addition, no growth inhibition was observed upon treating the cultures with indolokines 1-5 (data not shown). These studies support secreted indolokines as cellular stress-enhanced, bacterial cell-extrinsic factors, that enhance persister cell formation and likely account at least in part for the prior aspC genetic studies. The metabolite concentrations that we observed in cultures are consistent with known bacterial signaling molecules, such as cholera autoinducer-1 (CAI-1, ~0.3 μM) (Kelly et al., 2009), autoinducer-2 (AI-2, ~2 μM) (Fitts et al., 2016), and 3,5-dimethylpyrazin-2-ol (DPO, ~1 μM) (Papenfort et al., 2017).

Figure 4. Evaluation of indolokine 1-9 biological activities.

A, Persister cell formation of E. coli BW25113 pretreated with or without 1-5 in the presence of gentamicin. n = 4 biological replicates. Data are mean ± s.d. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Two-tailed t-test. B, Growth analysis of the virulent plant pathogen P. syringae pv. tomato (Pto) DC3000 in surface-inoculated adult leaves of A. thaliana. 5-week-old leaves were pre-infiltrated (pre-immunized) with 1 μM flg22 and 1 μM compounds (1-9) 24 h prior to infiltration with OD600 = 0.0002 bacteria. n = 6 (2, 5-9, ICN, and 4-OH-ICN) or 12 (DMSO, 3, and 4) biological replicates. Data are mean ± s.d. *P< 0.05, ****P< 0.0001. n.s., not significant. Two-tailed t-test. C, BioMAP® Phenotypic Profiling assay with metabolites 1-9 (21 μM). Cell types and stimuli used in each system are as follows: 3C system [HUVEC + (IL-1β, TNFα and IFNγ)], 4H system [HUVEC + (IL-4 and histamine)], LPS system [PBMC and HUVEC + LPS (TLR4 ligand)], SAg system [PBMC and HUVEC + TCR ligands (1×)], BT system [CD19+ B cells and PBMC + (α-IgM and TCR ligands (0.001×))], BF4T system [bronchial epithelial cells and HDFn + (TNFα and IL-4)], BE3C system [bronchial epithelial cells + (IL-1β, TNFα and IFNγ)], CASM3C system [coronary artery smooth muscle cells + (IL-1β, TNFα and IFNγ)], HDF3CGF system [HDFn + (IL-1β, TNFα, IFNγ, EGF, bFGF and PDGF-BB)], KF3CT system [keratinocytes and HDFn + (IL-1β TNFα and IFNγ)], MyoF system [differentiated lung myofibroblasts + (TNFα and TGFβ)] and /Mphg system [HUVEC and M1 macrophages + Zymosan (TLR2 ligand)]. D, AhR activating properties of 2-5 and ITE (positive control). n = 3 biological replicates. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Non-marked data in panel D were not significant relative to controls. Two-tailed t-test.

Plant-defensive responses of indolokines against pathogenic bacteria

Indolokines A2-A5 (4, 5, 2, and 3, respectively) and their 4-hydroxylated derivatives B2-B5 (8, 9, 6, and 7, respectively) are derived from indole-3-carbonyl nitrile (ICN) and 4-hydroxy-1H-indole-3-carbonyl nitrile (4-OH-ICN), respectively, in Arabidopsis thaliana as part of a pathogen-induced P450-mediated plant defense response against various biotic stresses (Barco et al., 2019; Rajniak et al., 2015). 4-OH-ICN and 4-hydroxylated indolokines 6-9 are derived from ICN via a single plant P450, CYP82C2. ICN and 4-OH-ICN alter plant defense responses to bacterial pathogens via an unknown signaling mechanism (Barco et al., 2019; Rajniak et al., 2015), and it is unclear if their spontaneous indolokine breakdown products contribute to these responses. Small molecule defense responses are a hallmark of sessile plants, and previously identified lineage-specific plant defense metabolites have been shown to interact with evolutionarily conserved proteins to alter their activities (Katz et al., 2015; Malinovsky et al., 2017). Since the biosynthetic precursor of indolokines 6-9, 4-OH-ICN, showed plant protective activity against pathogenic bacteria (Rajniak et al., 2015), we challenged A. thaliana with the virulent bacterial hemibiotroph Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pto) DC3000 after pre-immunizing the plant with 1 μM of Pseudomonas-derived flagellin peptide flg22, and 1 μM of individual 2-9 or their labile plant precursors ICN and 4-OH-ICN (metabolite 1 was substrate limited). We found that indolokine A5 (3) conferred an order of magnitude of protective effect against bacterial infection, whereas indolokine A2 (4) and B3 (9) provided protection up to two orders of magnitude over controls (Figure 4B). Surprisingly, 4-OH-ICN, which was described as having a weak protective effect (Rajniak et al., 2015), had no significant effect in our current study. We also looked at pathogen-triggered callose (β-1,3-glucan) deposition on plant cell walls, which is a hallmark plant immune response to microbial infection and physical damage (Ellinger and Voigt, 2014). In this assay, we found that indolokine A2 (4) conferred increased callose deposition in the presence of both flg22 and E. coli-derived bacterial elongation factor Tu peptide elf26, which have been previously described to elicit plant defense responses (Kunze et al., 2004; Zipfel et al., 2004), whereas plant indolokine B3 (9) conferred greater callose deposition in the presence of elf26 peptide (Figure S4). These data suggest that the indolokines contribute to the regulation of an ancient innate immune response in plants. Strikingly, our studies suggest that the metabolites are derived from convergent evolution between plants (Rajniak et al., 2015) and bacteria (Figure 2A) to similarly regulate cellular defensive responses.

Assessment of human primary cell responses to indolokines

Because the indolokines can be detected in feces and are produced in common gut bacteria (Figure 2), we evaluated their potential functional roles in primary human tissues using the BioMAP® Phenotypic Profiling Assay system. We screened the nine indolokines 1-9 (21 μM) against this panel of 12 human primary cell-based co-culture systems (venular endothelial cells, lung fibroblasts, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, PBMCs) that model various tissues and diseases (Figure 4C). Protein biomarker readouts in these mixed cell systems were used to quantify the effects of the nine metabolites. Interestingly, Indolokine A4 (2) showed a very robust ~30-fold increase (relative to vehicle control) of interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion from CD19+ B cells co-cultured with PMBCs. Indolokine A4 (2) also increased interleukin-8 (IL-8) in venular endothelial cells co-cultured with PBMCs, caused a decrease in proliferation in dermal fibroblasts, and decreased eotaxin-3 (CCL26) in both venular endothelial cells (mono-culture) and bronchial epithelial cells co-cultured with dermal fibroblasts. These results suggest the role of indolokine A4 (2) in affecting immunomodulatory and inflammation-related activities. Indolokine B4 (6) caused a decrease in matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9), urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (CD87), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and C-X-C chemokine 11 (CXCL-11), all of which are associated with tissue remodeling.

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) agonistic effect of indolokines

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a cytoplasmic receptor and transcription factor in humans that plays important roles in immunity and tissue homeostasis (Shinde and McGaha, 2018). Dysregulation of AhR signaling has been associated with autoimmune diseases and cancer (Shinde and McGaha, 2018). Aromatic hydrocarbons including indole-functionalized metabolites produced by the human gut microbiome are known to activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and regulate innate immune responses (Shinde and McGaha, 2018; Zelante et al., 2013). Indeed, indolokine A5 (3), in particular, is the demethylated analog of a very potent AhR agonist 2-(1′H-indole-3′-carbonyl)-thiazole-4-carboxylic acid methyl ester (ITE) (Song et al., 2002). Consistent with our human functional profiling results, AhR agonists including ITE regulate IL-6 secretion from immune cells, such as dendritic cells (Wang et al., 2014) and macrophages (Shinde et al., 2018). Thus, we proposed that indolokine A4 (2) would more strongly regulate the AhR pathway relative to 3-5, which would be consistent with its very robust IL-6 secretion phenotype. To test this proposal, we evaluated indolokines 2-5 (up to 10 μM) against a commercial human AhR reporter cell line utilizing a beetle luciferase gene downstream of dioxin/xenobiotic response elements (DRE/XRE). All of the indolokines tested showed AhR activation at sub- and low-micromolar concentrations, which is consistent with the concentrations that we observed in stationary phase cultures (Figure 4D). As anticipated from the IL-6 responses, indolokine A4 (2), the most abundant indolokine measured in mouse fecal samples, significantly activated the AhR pathway at 100 nM and higher and was more potent than its oxidized A5 (3) variant (i.e., the demethylated analog of ITE). While ITE has become an important chemical model in the AhR regulation field (Shinde and McGaha, 2018), ITE was originally isolated from pig lung using acid and methanol extraction conditions (Song et al., 2002). This suggests that ITE may be a synthetic artefact (i.e., a Fischer esterification of 3). Consistent with this notion, we were unable to detect ITE in the fecal samples using our neutral extraction conditions. Moreover, we extracted E. coli BW25113 cultures using the prior extraction conditions and could detect ITE, whereas our neutral extraction conditions did not lead to detectable levels of the small molecule (see general synthetic procedures). Given the largely microaerobic conditions at the gut host-microbe interface (Carlson-Banning and Sperandio, 2018), our results support indolokine A4 (2) as a more ecologically-relevant AhR model than ITE.

Conclusion

Modern analytical methods have revealed that the majority of metabolites found in the intestinal tract remain unknown (Dorrestein et al., 2014). Some of the small molecules from this so called “dark matter” of the intestinal metabolome will regulate the compositions and activities of the intestinal microbiota and/or modulate host cell responses that could significantly affect human health and disease. Indeed, some indole-functionalized metabolites at often high concentrations (sub-mM to mM) can regulate bacterial cellular stress responses (Bianco et al., 2006; Garbe et al., 2000; Hirakawa et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2007; Vega et al., 2012), and consistently, select indole metabolites accumulate to high concentrations in the intestinal tract, leading to immunological responses (Dodd et al., 2017; Hubbard et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2014; Zelante et al., 2013). In the current study, we describe a family of indole-functionalized bacterial metabolites termed the indolokines (1-5) that harbor high potency for both persister cell activation in bacteria (5 μM, aerobic conditions in vitro) and immune activation in human host tissues (100 nM). One indolokine is a previously unreported small molecule (1) and four of the indolokines (2-5) are shared with the pathogen-defense response of plants (Rajniak et al., 2015). Strikingly, we show here that select members of the indolokines protect plants against bacterial infection with higher efficacy than the known plant indolokine precursors ICN and 4-OH-ICN (Rajniak et al., 2015) in part through increased plant cell wall reinforcement, a phenomenon which has also been observed in Arabidopsis by indole glucosinolates (Clay et al., 2009). In bacterial culture conditions, we show that the indolokines can be produced spontaneously from I3P and l-Cys (or l-Cys-Gly), representing a striking example of convergent evolution at both the structural and phenotypic cellular defense levels. Our studies are also consistent with prior genetic studies implicating aromatic amino acid transamination as a defense strategy against drug stress conditions (Mathieu et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2015), which likely extend to other human pathogens (e.g., Figure 2). Intriguingly, indolokine A4 (2) very robustly regulated IL-6 secretion in human B-cells, which was consistent with 2 being the most potent AhR agonist among the natural metabolite family. Collectively, our studies define a bacterial cellular stress response in a common member of the human microbiota at the molecular level and link it to conserved interkingdom cellular defense signaling.

Significance

Bacteria produce tens of thousands of small molecule metabolites with unknown functions in the human intestinal tract. Some of those may regulate the composition and activity of the microbiome and/or modulate host immunity. Using host inflammation-mimetic conditions (i.e., ROS) to prioritize metabolite characterization efforts led to the characterization of the indole metabolites termed “indolokines,” which are found in E. coli and other Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The broad distribution of metabolites in the selected bacteria and in mouse fecal samples is consistent with their spontaneous biosynthesis from reactive thiols (i.e., l-Cys and l-Cys-Gly) and indole-3-pyruvate derived from AspC/TyrB-mediated transamination. Intriguingly, the bacterial metabolites are derived from a convergent evolutionary process relative to the ICN pathway described in plants. Strikingly, the spontaneous chemical processing observed here appears to be monitored by both the bacteria and the eukaryotic hosts, including the enhancement of bacterial persister cell formation, activation of IL-6 in human immune cells, and protection of plants from bacterial infection. Thus, these studies support a new interkingdom cellular defense strategy conserved among bacteria, plants, and mammals.

STAR★METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact: Jason M. Crawford (jason.crawford@yale.edu). There are restrictions to the availability of indolokines due to synthesis requirements.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Microbial Strains

Please refer to key resource table for the complete list.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli BW25113 | CGSC | 7636 |

|

E. coli JW4014-2 (ΔtyrB747::kan) |

CGSC | 10886 |

|

E. coli JW0911-1 (ΔaspC745::kan) |

CGSC | 8924 |

| E. coli BW25113 ΔtyrB/ ΔaspC | (Park et al., 2019) | N/A |

| E. coli MG1655 | CGSC | 6300 |

| E. coli Nissle 1917 | ArdeyPharm | N/A |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | Dr. MacMicking (Yale School of Medicine) | N/A |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC | 700603 |

| X. bovienii str. feltiae Moldova | Dr. Heidi Goodrich-Blair (University of Wisconsin-Madison) | N/A |

| V. cholerea El Tor N16961 ΔctxAB | Dr. Waldor (Harvard Medical School) | N/A |

| V. parahaemolyticus | Dr. Waldor (Harvard Medical School) | N/A |

| P. aeruginosa PA01 | Dr. Strobel (Yale University) | N/A |

| E. faecalis | Dr. Kriegel (Yale School of Medicine) | N/A |

| E. gallinarum | Dr. Kriegel (Yale School of Medicine, (Manfredo Vieira et al., 2018)) | N/A |

| L. parafarraginis F0439 | BEI Resources | HM-478 |

| L. rhamnosus LMS2-1 | BEI Resources | HM-106 |

| L. reuteri CF48-3A | BEI Resources | HM-102 |

| B. subtilis BR151 | Dr. Kolter (Harvard Medical School) | N/A |

| S. aureus | ATCC | 23235 |

| P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 | (Cuppels, 1986) | N/A |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Mouse fecal sample | (Park et al., 2019) | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Paraquat | Acros Organics | Cat # AC227320010 |

| Erythromycin | Acros Organics | Cat # 227330050 |

| L-Cysteine | Alfa Aesar | Cat # J63745 |

| Indole-3-pyruvic acid | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat # SC-218597 |

| ITE | Tocris | Cat # 1803 |

| Kanamycin sulfate | AmericanBio | Cat # AB01100-00010 |

| Rifampicin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # R3501-250MG |

| Gentamicin sulfate | Acros | Cat # 455310010 |

| Manganese(IV) oxide | Beantown Chemical | Cat # 129129-100G |

| 4-Hydroxyindole-3-carboxaldehyde | ChemCruz | Cat # sc-262003 |

| DDQ (2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone) | Alfa Aesar | Cat # A11879 |

| LB | Difco | Cat # 244620 |

| M9 | VWR | Cat # J863-500G |

| Fafard Growing Mix 2 | Sun Gro Horticulture, Vancouver, Canada | N/A |

| Vermiculite | Scotts, Marysville, OH | N/A |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Human AhR Reporter Assay System | Indigo Biosciences | Cat # IB06001 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Plant: Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 | ABRC | Cat # CS1092 |

| S. cerevisiae | ATCC | 9763 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pET-28a (+) | Addgene | Cat # 69864-3 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ChemDraw 19.0 | PerkinElmer | https://www.perkinelmer.com/product/chemoffice-professional-chemofficepro |

| Mnova | Mestrelab Research | https://mestrelab.com/download/mnova/ |

| Prism 8 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Adobe Illustrator CC 2018 | Adobe | https://www.adobe.com/products/illustrator.html |

| BioRender | BioRender | biorender.com |

| Others | ||

| Amberlite XAD-7 HP | Acros Organics | Cat # 202245000 |

| Celite | Acros Organics | Cat # 349675000 |

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana accession Columbia-0 (Col-0) plants were grown on soil [3:1 mix of Fafard Growing Mix 2 (Sun Gro Horticulture, Vancouver, Canada) to vermiculite (Scotts, Marysville, OH)] at 22 °C daytime/18 °C nighttime with 60% humidity under a 12-hr light cycle [50 (dawn/dusk) and 100 (midday) μE m-2 s-1 light intensity].

METHOD DETAILS

Instrumentation

Low-resolution LC-MS data were obtained using an Agilent 6120 single quadrupole LC-MS system and an Agilent 6490 Triple-Quad (QQQ) fitted with an ESI source coupled to Infinity 1290 HPLC system and a Kinetex 1.7 μm C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm) with a water:acetonitrile linear gradient containing 0.1% formic acid at 0.3 mL/min: 0-18 min, 15% to 100% acetonitrile. High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) data were obtained using an Agilent iFunnel 6550 quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) instrument fitted with an ESI source coupled to an Agilent 1290 Infinity HPLC system and a Kinetex 5μ C18 100 Å column (250 × 4.6 mm) with a water:acetonitrile gradient containing 0.1% formic acid at 0.7 mL/min: 0-30 min, 5 to 100% acetonitrile. The mass spectra were recorded in positive ionization mode with a mass range from m/z 100 to 1,700. 10 ppm mass windows were used to generate extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) spectra and then to measure the metabolite production levels (1, m/z 360.0649; 2, m/z 275.0485; 3, m/z 273.0328; 4, m/z 332.0700; 5, m/z 330.0543). Isolation of metabolites was performed using an Agilent Prepstar high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system with an Agilent Polaris C18-A 5 μm (250 × 21.2 mm2) column and a Phenomenex Luna C18 (2) 100 Å (250 × 10 mm) column. 1D (1H and 13C) and 2D (gCOSY, gHSQCAD, gHMBCAD, and LR-HSQMBC) NMR spectral data were measured on Agilent 400 or 600 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a cold probe with a 3-mm tube, and the chemical shifts were recorded as δ values (ppm) referenced to solvent residual signals.

Metabolite detection from wild-type E. coli BW25113 and its aromatic amino acid aminotransferase mutants

Fresh single colonies of E. coli BW25113 and its three aromatic amino acid aminotransferase mutants (ΔtyrB, ΔaspC, and ΔtyrB/ΔaspC) were used to inoculate 5 mL of M9-Glucose medium (0.4% D-glucose), and the cultures were grown overnight at 37 °C under aerobic conditions (250 rpm). After 48 hrs of cultivation, the cultures were centrifuged for 20 mins at 1500 × g to remove the cells. 6 mL of water-saturated n-butanol was added to each supernatant, which was vortexed for 10 seconds and centrifuged for 5 mins at 1500 × g. The top 5 mL of the organic layer was transferred and dried in vacuo. The dried extracts were dissolved in 200 μL of methanol, and 10 μL of each sample was injected into the QTOF LC-MS instrument for metabolite analysis.

Metabolite detection from diverse bacteria cultures

Four strains of E. coli (Nissle 1917, MG1655, BW25113, and LF82), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603, X. bovienii str. feltiae Moldova, V. cholerea El Tor N16961 ΔctxAB, V. parahaemolyticus, P. aeruginosa PAO1, vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis (VRE), E. gallinarum, and methicillin-resistant S. aureus ATCC BAA-1717 (MRSA) were grown for 48 h at 37 °C in LB. L. reuteri CF48-3A, L. parafarraginis F0439, and L. rhamnosus LMS2-1 were grown in Lactobacilli MRS broth at 37 °C for 48 h. B. subtilis BR151 and S. cerevisiae were grown at 30 °C for 48 h in LB and yeast malt broth, respectively. In order to induce cellular stress in E. coli, five different concentrations of paraquat (3, 6, 12, 25, and 50 mM; Acros Organics, Nidderau, Germany) were added into the E. coli Nissle 1917 cultures at OD600 = ~0.5, and 25 μg/mL of erythromycin was supplemented to the X. bovienii cultures at the beginning of cultivation. LC-MS samples for these bacteria cultures and their corresponding media controls were prepared as described above.

Metabolite detection from mouse fecal samples

The mouse fecal samples were derived from our prior study (Park et al., 2019); mouse experiments were not conducted in the current study. Briefly, before colonization, 8-10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were fasted for 4 hrs followed by gavage of kanamycin (20 mg). After 20 hrs, mice were fasted again for 4 hrs and administrated with 1×104 kanamycin resistant E. coli (BW25113 wild-type carrying pET-28a (+) plasmid). Fecal pellets were collected 7 days post colonization and sonicated in methanol (HPLC grade) followed by centrifugation. Supernatants were dried in vacuo and resuspended in 100 μL of methanol and analyzed by QTOF LC-MS.

Isolation and characterization of metabolites

Single colonies of X. bovienii were used to inoculate four 5 mL of LB medium, and the cultures were grown overnight at 30 °C under aerobic conditions (250 rpm). Four 1 L of fresh LB medium with 25 μg/mL of erythromycin in 4 L Erlenmeyer flasks were inoculated by the overnight cultures and further incubated for 48 h at 30 °C. After removal of the cells by centrifugation for 20 mins at 13000 × g, 20 g/L of Amberlite® XAD-7 HP resins were added to the supernatant, which was shaken using 150 rpm for 30 mins. The resins were recovered by filtration using a glass frit under vacuum and extracted with 1 L of methanol to give crude extract (4.1 g). The dried extract was re-suspended with 100 mL of methanol and dried in the presence of 4 g of Celite® adsorbent. The extract-Celite® mixture was loaded onto pre-packed reversed-phase C18 resins (300 g) and separated using a step gradient with the following solvent composition (each 500 mL): Fraction 1, 10% aqueous methanol; Fraction 2, 20% aqueous methanol; Fraction 3, 30% aqueous methanol; Fraction 4, 40% aqueous methanol; Fraction 5, 50% methanol; Fraction 6, 100% methanol. Fraction 1 was further fractionated by an Agilent Prepstar HPLC system with an Agilent Polaris C18-A 5 μm (250 × 21.2 mm2) column with a gradient elution from 10 to 100% aqueous acetonitrile with 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 mins and flow rate of 8 mL/min using a 1 min fraction collection time window. Fraction 1-15 was purified using a Phenomenex Luna C18 (2) 100 Å column (250 × 10 mm, flow rate 4.0 mL/min, a gradient elution from 10 to 100% aqueous acetonitrile with 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 mins) to give compound 1 (tR = 12.7 min, 2.0 mg). Fraction 3 was separated and purified by the same method as Fraction 1 and compound 5 was obtained (tR = 16.0 min, 3.0 mg). The chemical structures of 1 and 5 were elucidated by 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy (1H, 13C, gCOSY, gHSQCAD, gHMBCAD, and LR-HSQMBC, Table S1, see NMR catalog). The structures of compounds 2-4 were confirmed by comparing retention times of synthetic materials (Figure S3).

Indolokine A8 (1):

Yellow powder; UV (acetonitrile:water = ~1:1 with 0.1% formic acid) λmax 218, 276, 410 nm; 1H (600 MHz) and 13C (125 MHz) NMR data, see Table S1; HR-ESI-QTOF-MS (positive-ion mode) m/z 360.0642 [M + H]+(calcd for C16H14N3O5S+, m/z 360.0649).

Biomimetic synthesis of 2 and 3

1 mM of l-Cys and/or I3P in M9-Glucose (0.4% D-glucose) or LB medium (three replicates) were shaken at 37 °C for 48 hrs. The reaction mixtures were extracted with n-butanol and dried in vacuo for LC-MS analysis as described above. The same experiments were performed in the absence of either l-Cys or I3P and both l-Cys and I3P in M9 or LB media.

Time-course analysis of metabolites in E. coli

Overnight cultures of E. coli Nissle 1917 were used to inoculate three biological replicates of 5 mL of fresh LB medium. These cultures were extracted with water-saturated n-butanol at three different time points (12, 24, and 48 hrs) of incubation, and then the dried materials were dissolved in 200 μL of methanol for QTOF LC-MS analysis as described above.

Quantification of 3 and 5 in E. coli

The method of standard addition was performed to quantify the concentration of 3 and 5 produced by E. coli. An overnight culture of E. coli BW25113 in LB was used to inoculate 200 mL of LB at a 1:100 dilution. Then the cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 2 days and aliquoted into 27 × 14-mL polypropylene culture tubes each containing 5 mL of the cultures. After different amounts of synthetic 3 and 5 (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 μL) from stock solutions (214 μM in DMSO) was added to the cultures to make the final concentrations of 0, 0.04, 0.09, 0.13, and 0.17 μM, the cultures extracted with 6 mL of water-saturated n-butanol. The extract was centrifuged and 5 mL of n-butanol layer was transferred and dried with reduced pressure. The dried crude extract was re-dissolved with 200 μL of methanol and subjected to QQQ LC-MS instrument for analysis. The dynamic MRM mode was used to monitor 3 and 5 with the following transitions: 3, 273.03 to 144, CE 17; 5, 330.05 to 144, CE 25.

Detection of indolokine A5 (3), its methyl ester (ITE), and ethyl ester from E. coli

2-day cultures of E. coli BW25113 (5 mL) were lyophilized and individually extracted with neutral methanol in room temperature, methanol with 1 N HCl in 100 °C for 1 hr, or ethanol with 1 N HCl in 100 °C for 1 hr. After the organic solvents were evaporated, the dried samples were resuspended with 500 μL of methanol and centrifuged. 200 μL of supernatant was transferred to LC-MS vial for analysis. Acid facilitated esterification as expected, suggesting that ITE previously isolated from pig lung may be a synthetic artefact.

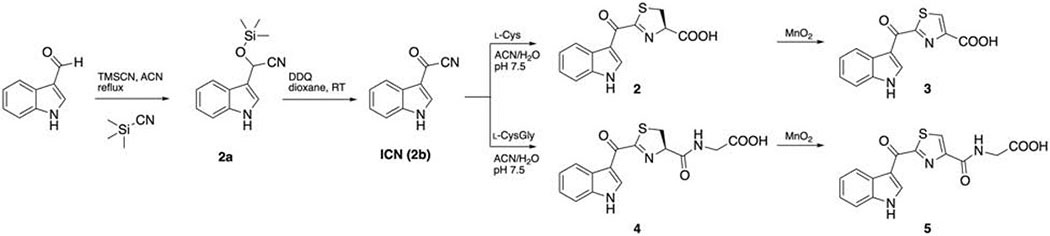

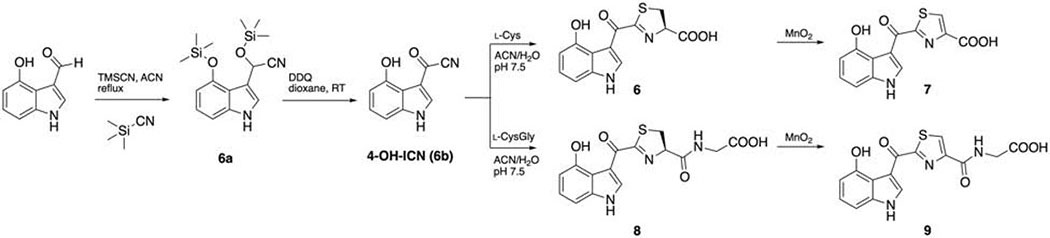

Synthetic procedures for indolokines

Synthesis routes were adopted from the previous protocol (Rajniak et al., 2015) with minor modifications. (Scheme 1,2) All the reactions were performed in single-neck round bottom flasks. Flash chromatography was performed with an Isolera™ Biotage system and C18 HPLC. The identity and purity of the compounds were determined through high resolution mass spectrometry and 1H-NMR.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of indolokines 2-5.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of indolokine 6-9.

Synthesis of 2a

To a solution of indole-3-carboxyaldehyde (1.52 g, 10.5 mmol) in anhydrous acetonitrile (10 mL) was added TMSCN (2 mL, 16 mmol), and the mixture was heated to reflux for 2.5 hrs. The solvent was evaporated and subjected to flash chromatography (n-hexane/ethyl acetate, with a linear gradient from 0% to 60% ethyl acetate in 15 column volumes) to afford 2a as black oil (2.10 g, 8.59 mmol, 82%). 1H NMR (chloroform-d) δ 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.71 (m, 1H), 7.40 (m, 2H), 7.16-7.27 (m, 2H), 5.81 (m, 1H), 0.20 (s, 9H).

Synthesis of ICN (2b)

To a solution of 2a (2.10 g, 8.59 mmol) in anhydrous 1,4-dioxane (5 mL) was gradually added DDQ (1950 mg, 8.59 mmol) dissolved in anhydrous 1,4-dioxane (13 mL) and stirred overnight. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, subjected to flash chromatography with dichloromethane, and yielded a grey solid (970 mg, 66%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 12.89 (s, 1H), 8.63 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (m, 1H), 7.57 (m, 1H), 7.33 (m, 2H).

Synthesis of Indolokine A4 (2)

To a solution of l-cysteine (712 mg, 5.88 mmol) in pH 7.5 sodium phosphate buffer (8 mL) was gradually added ICN (250 mg, 1.47 mmol) in acetonitrile (15 mL). The solution was degassed, purged with N2 and reacted overnight. The solution was dried down and purified with preparative reverse phase HPLC system equipped with an Agilent Polaris C18-A 5 μm (250 × 21.2 mm2) column (flow rate 8.0 mL/min, a gradient elution from 35% to 65% acetonitrile in water with 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 min) and yielded 2.2 mg. 1H NMR (methanol-d4) δ 8.71 (s, 1H), 8.26 (m, 1H), 7.48 (m, 1H), 7.27 (m, 2H), 5.51 (dd, J = 9.8, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 3.63 (m, 2H). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calcd for C13H10N2O3S, 275.0485; found, 275.0491.

Synthesis of Indolokine A5 (3)

To a solution of crude indolokine A4 (2) in methanol/acetone 3:1 (8 mL) was added MnO2 (460 mg) and stirred overnight. The reaction was centrifuged and filtered to remove MnO2. The solution was dried down and purified with preparative reverse phase HPLC system equipped with an Agilent Polaris C18-A 5 μm (250 × 21.2 mm2) column (flow rate 8.0 mL/min, a gradient elution from 35% to 65% acetonitrile in water with 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 min) and yielded 2.5 mg. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 12.32 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 9.14 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.31 (m, 1H), 7.59 (m, 1H), 7.30 (m, 2H). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calcd for C13H8N2O3S, 273.0328; found, 273.0339.

Synthesis of Indolokine A2 (4)

To a solution of l-Cys-Gly dipeptide (32.9 mg, 0.113 mmol) in pH 7.5 sodium phosphate buffer (3.5 mL) was gradually added ICN (23.8 mg, 0.14 mmol) in acetonitrile (3 mL). The solution was stirred overnight at room temperature. The solution was dried down and purified with preparative reverse phase HPLC system equipped with an Agilent Polaris C18-A 5 μm (250 × 21.2 mm2) column (flow rate 8.0 mL/min, a gradient elution from 35% to 65% acetonitrile in water with 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 min) and yielded 2.2 mg. 1H NMR (methanol-d4) δ 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.28 (m, 1H), 7.48 (m, 1H), 7.27 (m, 2H), 5.47 (t, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 4.03 (s, 2H), 3.61 (m, 2H). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calcd for C15H13N3O4S, 332.0700; found, 332.0707.

Synthesis of Indolokine A3 (5)

To a solution of crude Indolokine A2 (4) in methanol/acetone 1:3 (8 mL) was added MnO2 (658 mg) and stirred overnight. The reaction was centrifuged and filtered to remove MnO2. The solution was dried down and purified with preparative reverse phase HPLC system equipped with an Agilent Polaris C18-A 5 μm (250 × 21.2 mm2) column (flow rate 8.0 mL/min, a gradient elution from 35% to 65% acetonitrile in water with 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 min) and yielded 2.2 mg. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 12.35 (s, 1H), 9.41 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 9.06 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 8.33 (m, 1H), 7.58 (m, 1H), 7.30 (m, 2H), 4.02 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H).HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calcd for C15H11N3O4S, 330.0543; found, 330.0549.

Synthesis of 4-OH-indole cyanohydrin (6a)

To a solution of 4-OH-indole-3-carboxaldehyde (0.098 g, 0.61 mmol) in anhydrous acetonitrile (2 mL) was added TMSCN (172 μL, 1.34 mmol). The mixture was heated at reflux for 2.5 hrs. The solvent was evaporated, and the brown material was subjected to flash chromatography (n-hexane/ethyl acetate, with a linear gradient from 0% to 100% ethyl acetate in 16 column volume) to afford 4-OH-indole cyanohydrin (6a) as maroon oil (104 mg, 0.313 mmol, 51%). 1H NMR (chloroform-d) δ 8.83 (s, 1H), 7.27 (m, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H) 6.52 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (s, 1H), 0.42 (s, 9H), 0.15 (s, 9H).

Synthesis of 4-OH-ICN (6b)

To a solution of 6a (100.0 mg, 0.301 mmol) in anhydrous 1,4-dioxane (2 mL) was added DDQ (140 mg, 0.617 mmol) dissolved in anhydrous 1,4-dioxane (4 mL) and stirred overnight. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, subjected to flash chromatography with dichloromethane, and yielded a yellow oil (110 mg, >100%). Only a fraction of 4-OH-ICN was silylated and was subjected to the next step directly. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.65 (s, 1H), 8.70 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H).

Synthesis of Indolokine B4 (6)

To a solution of l-cysteine (174 mg, 1.44 mmol) in pH 7.5 sodium phosphate buffer (4 mL) was gradually added 4-OH-ICN (60mg, 0.32 mmol) in acetonitrile (2 mL). The solution was degassed, purged with N2 and reacted overnight. The solution was dried down and extracted with ethyl acetate and 5% citric acid (aq). The ethyl acetate layer was collected, dried down and purified with preparative reverse phase HPLC system equipped with an Agilent Polaris C18-A 5 μm (250 × 21.2 mm2) column (flow rate 8.0 mL/min, a gradient elution from 35% to 65% acetonitrile in water with 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 min) and yielded 1.0 mg. 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.85 (s, 1H), 7.14 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 5,43 (m, 1H), 3.65 (m, 2H). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calcd for C13H10N2O4S, 291.0434; found, 291.0438.

Synthesis of Indolokine B5 (7)

To a solution of crude indolokine B4 (6) in methanol/acetone 1:1 (4 mL) was added MnO2 (200 mg) and stirred overnight. The reaction was centrifuged and filtered to remove MnO2. The solution was dried down and purified with preparative reverse phase HPLC system equipped with an Agilent Polaris C18-A 5 μm (250 × 21.2 mm2) column (flow rate 8.0 mL/min, a gradient elution from 35% to 65% acetonitrile in water with 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 min) and yielded 2.2 mg. 1H NMR (methanol-d4) δ 9.44 (s, 1H), 8.66 (s, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.61 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H).HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calcd for C13H8N2O4S, 289.0278; found, 289.0287.

Synthesis of Indolokine B2 (8)/B3 (9)

To a solution of l-Cys-Gly dipeptide (275.9 mg, 0.945 mmol) in pH 7.5 sodium phosphate buffer (5 mL) was gradually added 4-OH-ICN (100 mg, 0.301 mmol) in acetonitrile (5 mL). The solution was stirred overnight at room temperature and monitored on LC/MS. Both B2 and B3 are observed ~1:1 ratio. The solution was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 mL × 3), dried and purified with HPLC.The solution was dried down and purified with preparative reverse phase HPLC system equipped with an Agilent Polaris C18-A 5 μm (250 × 21.2 mm2) column (flow rate 8.0 mL/min, a gradient elution from 35% to 65% acetonitrile in water with 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 min) and yielded B2 (8) 1.5 mg and B3 (9) 2.7 mg. 1H NMR δ 8.89 (s, 1H), 7.15 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (dd, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (dd, J = 7.9, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 5.48 (t, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 4.02 (s, 2H), 3.64 (m, 2H). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calcd for C15H13N3O5S, 348.0649; found, 348.0653. B3 (9) 1H NMR (methanol-d4) δ 9.43 (s, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (dd, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (dd, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (s, 2H). HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calcd for C15H11N3O5S, 346.0492; found, 346.0500.

Persister assay

The persister assay was performed as reported with minor modifications (Shan et al., 2015). Overnight LB cultures of E. coli BW25113 were diluted 1:50 in filtered M9-Glucose medium (0.4% d-glucose) at 37 °C for 6 hrs until OD600 0.5. Cultures were treated with 5 μM of compounds 1-5 in DMSO stock solution or the same amount of DMSO for negative vehicle control for 18 hours at 37 °C. Cultures were treated with 50 μg/mL gentamicin sulfate from a stock solution in water for another 24 hrs. For CFU counting, 20 μL of the culture was taken and serial diluted with cold PBS for both before and after antibiotic treatment. Appropriate dilution of the culture was plated on LB agar and incubated overnight in 37 μC incubator after spotted onto LB agar. The ratio of CFU/mL before and after antibiotic treatment was used as an indicator of persistence. Persistence data were plotted as bar graphs against survival percentage in the same way as other references (Kwan et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016).

Plant protection from bacterial infection

A single colony of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Pto DC3000) was used to inoculate 2 mL of LB containing 25 μg/mL rifampicin (Sigma-Aldrich). Bacteria were grown to log phase, washed in sterile water twice, resuspended in water to OD600 of 0.2, and incubated at room temperature with no agitation for 6 hr prior to infection. 5-week-old adult leaves were preinfiltrated with ~100 μL solution of 1 μM indolokines or DMSO and 1 μM flg22 for 24 hr prior to infiltration with the bacterial inoculum (OD600 = 0.0002 or 105 CFU/cm2 leaf area). Leaves were left to air-dry until not soaked and then plants were covered with humidity dome under high humidity (>80%) for 3 days. Leaves were then surface-sterilized in 70% ethanol for 10 sec, rinsed in sterile water, surface-dried on paper towels, and the bacteria were extracted into water, using an 8-mm stainless steel bead and a ball mill (20 Hz for 3 min). Serial dilutions of the extracted bacteria were plated on LB agar plates for colony-forming units (CFU) counting.

Callose deposition response assay

Seedlings were elicited with flg22, elf26, and/or 1 μM compounds for 16 h, and callose deposits were stained as previously described (Clay et al. 2009) and viewed under UV illumination using a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) Axio Observer D1 microscope equipped with a DAPI filer set (excitation filter 365 nm; dichroic mirror 395 nm; emission filter 445 nm (bandwidth 50 nm). Callose deposits were quantified using NIH Image J software.

AhR activation assay

Human Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) Reporter Assay System (96-well Format) was purchased from Indigo Biosciences and the protocol was followed as recommended. In brief, frozen reporter cell stock was thawed with Cell Recovery Medium (CRM) at 37 °C, and 100 μL of the cell suspension was transferred to a 96-well assay plate. All the compounds were prepared as 2× solution with Compound Screening Medium (CSM) provided, and 100 μL of this solution was added to designated wells and incubated at 37 °C. After incubation for 24 hours, medium was discarded and 100 μL of provided Luciferase Detection Reagent (LDR) was added, and luminescence was measured with Perkin Elmer Envision 2100 Multilabel plate reader.

BioMAP® Phenotypic Profiling Assay

BioMAP® Diversity PLUS assay was performed by Eurofins DiscoverX. Human primary cells in BioMAP systems were used at early passage (passage 4 or earlier) to minimize adaptation to cell culture conditions and preserve physiological signaling responses. All cells were from a pool of multiple donors (n = 2 – 6), commercially purchased and handled according to the recommendations of the manufacturers. Human blood derived CD14+ monocytes are differentiated into macrophages in vitro before being added to the /Mphg system. Abbreviations are used as follows: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), Human neonatal dermal fibroblasts (HDFn), B cell receptor (BCR), T cell receptor (TCR) and Toll-like receptor (TLR). Cell types and stimuli used in each system are as follows: 3C system [HUVEC + (IL-1β, TNFα and IFNγ)], 4H system [HUVEC + (IL-4 and histamine)], LPS system [PBMC and HUVEC + LPS (TLR4 ligand)], SAg system [PBMC and HUVEC + TCR ligands (1×)], BT system [CD19+ B cells and PBMC + (α-IgM and TCR ligands (0.001×))], BF4T system [bronchial epithelial cells and HDFn + (TNFα and IL-4)], BE3C system [bronchial epithelial cells + (IL-1β, TNFα and IFNγ)], CASM3C system [coronary artery smooth muscle cells + (IL-1β, TNFα and IFNγ)], HDF3CGF system [HDFn + (IL-1β, TNFα, IFNγ, EGF, bFGF and PDGF-BB)], KF3CT system [keratinocytes and HDFn + (IL-1β, TNFα and IFNγ)], MyoF system [differentiated lung myofibroblasts + (TNFα and TGFβ)] and /Mphg system [HUVEC and M1 macrophages + Zymosan (TLR2 ligand)]. Systems are derived from either single cell types or co-culture systems. Adherent cell types were cultured in 96- or 384-well plates until confluence, followed by the addition of PBMC (SAg and LPS systems). The BT system consists of CD19+ B cells co-cultured with PBMC and stimulated with a BCR activator and low levels of TCR stimulation. Metabolites 1-9 were prepared in DMSO (final concentration ≤ 0.1%) and added at a final concentration of 21 μM, 1 h before stimulation and remained in culture for 24 h or as otherwise indicated (48 h: MyoF system; 72 h: BT system (soluble readouts); 168 h: BT system (secreted IgG)). Each plate contained drug controls, negative controls (e.g., non-stimulated conditions) and vehicle controls (e.g., 0.1% DMSO) appropriate for each system. Direct ELISA was used to measure biomarker levels of cell-associated and cell membrane targets. Soluble factors from supernatants were quantified using either HTRF® detection, bead-based multiplex immunoassay or capture ELISA. Overt adverse effects of test agents on cell proliferation and viability (cytotoxicity) were detected by sulforhodamine B (SRB) staining, for adherent cells, and alamarBlue® reduction for cells in suspension. For proliferation assays, individual cell types were cultured at sub-confluence and measured at time points optimized for each system (48 h: 3C and CASM3C systems; 72 h: BT and HDF3CGF systems; 96 h: SAg system). Cytotoxicity for adherent cells was measured by SRB (24 h: 3C, 4H, LPS, SAg, BF4T, BE3C, CASM3C, HDF3CGF, KF3CT, /Mphg systems; 48 h: MyoF system), and by alamarBlue staining for cells in suspension (24 h: SAg system; 42 h: BT system) at the time points indicated.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. Two tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

This study did not generate any unique datasets or code not available in the manuscript files.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cellular stress induced indole metabolites termed indolokines in diverse bacteria

Indolokines were identified in fecal samples and enhanced E. coli persister cell formation

Indolokines outperformed known plant defense metabolites in Arabidopsis-Pseudomonas model

Indolokines activated human aryl-hydrocarbon receptor and induced IL-6 secretion

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Richard A. Flavell and Mr. Zheng Wei (Yale University School of Medicine) for providing mouse fecal samples. This work was supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Foundation (1016720 to J.M.C.), the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2019R1A6A3A12033304 to C.S.K.), and a fellowship from the Ministry of Education in Taiwan (to J.-H.L). We also acknowledge prior support from the National Institutes of Health (1DP2-CA186575 & R01CA215553 to J.M.C., T32-GM007499 to B.B.), the Camille & Henry Dreyfus Foundation (TC-17-011 to J.M.C.), Elsevier/Phytochemistry (to N.K.C.), and Yale University. The TOC image was created with BioRender.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

R.W., T.P.W., and G.P. are employees of Merck Exploratory Science Center, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Employees may hold stocks and/or stock options in Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

References

- Agus A, Massier S, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Billard E, and Barnich N (2014). Understanding host-adherent-invasive Escherichia coli interaction in Crohn’s disease: opening up new therapeutic strategies. BioMed research international 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asensio C, Pérez-Díaz JC, Martínez MC, and Baquero F (1976). A new family of low molecular weight antibiotics from enterobacteria. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 69, 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, and Mori H (2006). Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Molecular systems biology 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barco B, Kim Y, and Clay NK (2019). Expansion of a core regulon by transposable elements promotes Arabidopsis chemical diversity and pathogen defense. Nature communications 10, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco C, Imperlini E, Calogero R, Senatore B, Amoresano A, Carpentieri A, Pucci P, and Defez R (2006). Indole-3-acetic acid improves Escherichia coli’s defences to stress. Archives of Microbiology 185, 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bus JS, and Gibson JE (1984). Paraquat: model for oxidant-initiated toxicity. Environmental health perspectives 55, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson-Banning KM, and Sperandio V (2018). Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli outwits hosts through sensing small molecules. Current opinion in microbiology 41, 83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatagner F, and Sauret-Ignazi G (1956). Role of transamination and pyridoxal phosphate in the enzymatic formation of hydrogen sulfide from cysteine by the rat liver under anaerobiosis. Bulletin de la Societe de chimie biologique 38, 415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay NK, Adio AM, Denoux C, Jander G, and Ausubel FM (2009). Glucosinolate metabolites required for an Arabidopsis innate immune response. Science 323, 95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuppels DA (1986). Generation and characterization of Tn5 insertion mutations in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Appl Environ Microbiol 51, 323–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd D, Spitzer MH, Van Treuren W, Merrill BD, Hryckowian AJ, Higginbottom SK, Le A, Cowan TM, Nolan GP, and Fischbach MA (2017). A gut bacterial pathway metabolizes aromatic amino acids into nine circulating metabolites. Nature 551, 648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donia MS, and Fischbach MA (2015). Small molecules from the human microbiota. Science 349, 1254766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrestein PC, Mazmanian SK, and Knight R (2014). Finding the missing links among metabolites, microbes, and the host. Immunity 40, 824–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellermann M, and Arthur JC (2017). Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition and modulation of host-bacterial interactions. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 105, 68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinger D, and Voigt CA (2014). Callose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis with a focus on pathogen response: what we have learned within the last decade. Annals of botany 114, 1349–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts EC, Andersson JA, Kirtley ML, Sha J, Erova TE, Chauhan S, Motin VL, and Chopra AK (2016). New insights into autoinducer-2 signaling as a virulence regulator in a mouse model of pneumonic plague. mSphere 1, e00342–00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima T, Yamada K, Hojo N, Isobe A, Shiwaku K, and Yamane Y (1994). Mechanism of cytotoxicity of paraquat: III. The effects of acute paraquat exposure on the electron transport system in rat mitochondria. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology 46, 437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbe TR, Kobayashi M, and Yukawa H (2000). Indole-inducible proteins in bacteria suggest membrane and oxidant toxicity. Archives of microbiology 173, 78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand DH, and Steinberg RA (1977). Escherichia coli mutants deficient in the aspartate and aromatic amino acid aminotransferases. Journal of Bacteriology 130, 429–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q, Fang J, and Li J (2001). Kynurenine aminotransferase and glutamine transaminase K of Escherichia coli: identity with aspartate aminotransferase. Biochemical Journal 360, 617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanes C, Hird F, and Isherwood F (1950). Synthesis of peptides in enzymic reactions involving glutathione. Nature 166, 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa H, Inazumi Y, Masaki T, Hirata T, and Yamaguchi A (2005). Indole induces the expression of multidrug exporter genes in Escherichia coli. Molecular microbiology 55, 1113–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Kwan BW, Osbourne DO, Benedik MJ, and Wood TK (2015). Toxin YafQ increases persister cell formation by reducing indole signalling. Environmental microbiology 17, 1275–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard TD, Murray IA, Bisson WH, Lahoti TS, Gowda K, Amin SG, Patterson AD, and Perdew GH (2015). Adaptation of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor to sense microbiota-derived indoles. Scientific reports 5, 12689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin U-H, Lee S-O, Sridharan G, Lee K, Davidson LA, Jayaraman A, Chapkin RS, Alaniz R, and Safe S (2014). Microbiome-derived tryptophan metabolites and their aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent agonist and antagonist activities. Molecular pharmacology 85, 777–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RM, Mercante JW, and Neish AS (2012). Reactive oxygen production induced by the gut microbiota: pharmacotherapeutic implications. Current medicinal chemistry 19, 1519–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz E, Nisani S, Yadav BS, Woldemariam MG, Shai B, Obolski U, Ehrlich M, Shani E, Jander G, and Chamovitz DA (2015). The glucosinolate breakdown product indole-3-carbinol acts as an auxin antagonist in roots of A rabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 82, 547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RC, Bolitho ME, Higgins DA, Lu W, Ng W-L, Jeffrey PD, Rabinowitz JD, Semmelhack MF, Hughson FM, and Bassler BL (2009). The Vibrio cholerae quorum-sensing autoinducer CAI-1: analysis of the biosynthetic enzyme CqsA. Nature chemical biology 5, 891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CS, Gatsios A, Cuesta S, Lam YC, Wei Z, Chen H, Russell RM, Shine EE, Wang R, Wyche TP, et al. (2019). Characterization of autoinducer-3 biosynthesis in E. coli. ACS Central Science, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, and Sperandio V (2019). Indole Signaling at the Host-Microbiota-Pathogen Interface. mBio 10, e01031–01019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze G, Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Niehaus K, Boller T, and Felix G (2004). The N terminus of bacterial elongation factor Tu elicits innate immunity in Arabidopsis plants. The Plant Cell 16, 3496–3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan BW, Osbourne DO, Hu Y, Benedik MJ, and Wood TK (2015). Phosphodiesterase DosP increases persistence by reducing cAMP which reduces the signal indole. Biotechnology and bioengineering 112, 588–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan BW, Valenta JA, Benedik MJ, and Wood TK (2013). Arrested protein synthesis increases persister-like cell formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57, 1468–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Bansal T, Jayaraman A, Bentley WE, and Wood TK (2007). Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli biofilms are inhibited by 7-hydroxyindole and stimulated by isatin. Appl Environ Microbiol 73, 4100–4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-H, Kim Y-G, Gwon G, Wood TK, and Lee J (2016). Halogenated indoles eradicate bacterial persister cells and biofilms. AMB Express 6, 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-H, Wood TK, and Lee J (2015). Roles of indole as an interspecies and interkingdom signaling molecule. Trends in microbiology 23, 707–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinovsky FG, Thomsen M-LF, Nintemann SJ, Jagd LM, Bourgine B, Burow M, and Kliebenstein DJ (2017). An evolutionarily young defense metabolite influences the root growth of plants via the ancient TOR signaling pathway. Elife 6, e29353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredo Vieira S, Hiltensperger M, Kumar V, Zegarra-Ruiz D, Dehner C, Khan N, Costa FRC, Tiniakou E, Greiling T, Ruff W, el al. (2018). Translocation of a gut pathobiont drives autoimmunity in mice and humans. Science 359, 1156–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu A, Fleurier S, Frénoy A, Dairou T, Bredeche M-F, Sanchez-Vizuete P, Song X, and Matic I (2016). Discovery and function of a general core hormetic stress response in E. coli induced by sublethal concentrations of antibiotics. Cell reports 77, 46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurry T, and Begley TP (2016). The Organic Chemistry of Biological Pathways, 2nd edn (Greenwood Village: Roberts and Company Publishers; ). [Google Scholar]

- Meister A, and Tate SS (1976). Glutathione and related γ-glutamyl compounds: biosynthesis and utilization. Annual review of biochemistry 45, 559–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nougayréde J-P, Homburg S, Taieb F, Boury M, Brzuszkiewicz E, Gottschalk G, Buchrieser C, Hacker T, Dobrindt U, and Oswald E (2006). Escherichia coli induces DNA double-strand breaks in eukaryotic cells. Science 313, 848–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papenfort K, and Bassler BL (2016). Quorum sensing signal–response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nature Reviews Microbiology 14, 576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papenfort K, Silpe JE, Schramma KR, Cong J-P, Seyedsayamdost MR, and Bassler BL (2017). A Vibrio cholerae autoinducer–receptor pair that controls biofilm formation. Nature chemical biology 13, 551–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HB, Wei Z, Oh I, Xu H, Kim CS, Wang R, Wyche TP, Pnzzi G, Flavell RA, and Crawford JM (2019). Sulfamethoxazole drug stress upregulates redox active immunomodulatory metabolites in E. coli. in revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Park J-S, Yabe S, Shin-ya K, Nishiyama M, and Kuzuyama T (2015). New 2-(1′ H-indole-3 ′ -carbonyl)-thiazoles derived from the thermophilic bacterium Thermosporothrix hazakensis SK20-1 T. The Journal of antibiotics 68, 60–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajniak J, Barco B, Clay NK, and Sattely ES (2015). A new cyanogenic metabolite in Arabidopsis required for inducible pathogen defence. Nature 525, 376–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath CM, and Dorrestein PC (2012). The bacterial chemical repertoire mediates metabolic exchange within gut microbiomes. Current opinion in microbiology 15, 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romasi EF, and Lee J (2013). Development of indole-3-acetic acid-producing Escherichia coli by functional expression of IpdC, AspC, and Iad1. J Microbiol Biotechnol 23, 1726–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson M-A, Roy SL, Jones JL, and Griffin PM (2011). Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerging infectious diseases 17, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz M (2008). Clinical use of E. coli Nissle 1917 in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases 14, 1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secher T, Brehin C, and Oswald E (2016). Early settlers: which E. coli strains do you not want at birth? American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 311, G123–G129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah D, Zhang Z, Khodursky AB, Kaldalu N, Kurg K, and Lewis K (2006). Persisters: a distinct physiological state of E. coli. BMC microbiology 6, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y, Lazinski D, Rowe S, Camilli A, and Lewis K (2015). Genetic basis of persister tolerance to aminoglycosides in Escherichia coli. MBio 6, e00078–00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde R, Hezaveh K, Halaby MJ, Kloetgen A, Chakravarthy A, da Silva Medina T, Deol R, Manion KP, Baglaenko Y, and Eldh M (2018). Apoptotic cell-induced AhR activity is required for immunological tolerance and suppression of systemic lupus erythematosus in mice and humans. Nature immunology 19, 571–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde R, and McGaha TL (2018). The Aryl hydrocarbon receptor: connecting immunity to the microenvironment. Trends in immunology 39, 1005–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoog DA, Holler FJ, and Crouch SR (2017). Principles of Instrumental Analysis, 6th edn (Cengage learning; ). [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Clagett-Dame M, Peterson RE, Hahn ME, Westler WM, Sicinski RR, and DeLuca HF (2002). A ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor isolated from lung. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99, 14694–14699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenborn U (2016). Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917—from bench to bedside and back: history of a special Escherichia coli strain with probiotic properties. FEMS microbiology letters 363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandio V, Torres AG, Jarvis B, Nataro JP, and Kaper JB (2003). Bacteria–host communication: the language of hormones. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100, 8951–8956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenaillon O, Skurnik D, Picard B, and Denamur E (2010). The population genetics of commensal Escherichia coli. Nature Reviews Microbiology 8, 207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega NM, Allison KR, Khalil AS, and Collins JJ (2012). Signaling-mediated bacterial persister formation. Nature chemical biology 8, 431–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Ye Z, Kijlstra A, Zhou Y, and Yang P (2014). Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor affects activation and function of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 177, 521–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Zeng F, Bie Q, Dai C, Chen C, Tong Q, Liu J, Wang J, Zhou Y, and Zhu H (2018). Cytochathiazines A-C: Three Merocytochalasans with a 2 H-1, 4-Thiazine Functionality from Coculture of Chaetomium globosum and Aspergillus flavipes. Organic letters 20, 6817–6821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, Kim CS, Healy AR, Wernke KM, Wang Z, Frischling MC, Shine EE, Wang W, Herzon SB, and Crawford JM (2019). Structure elucidation of colibactin and its DNA cross-links. Science 365, eaax2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelante T, Iannitti RG, Cunha C, De Luca A, Giovannini G, Pieraccini G, Zecchi R, D’Angelo C, Massi-Benedetti C, and Fallarino F (2013). Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 39, 372–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Navarro L, Oakeley EJ, Jones JD, Felix G, and Boller T (2004). Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature 428, 764–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate any unique datasets or code not available in the manuscript files.