Abstract

Malaria is one of the serious health problems in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Its treatment has been met with chronic failure due to pathogenic resistance to the currently available drugs. This review attempts to compile phytotherapeutical information on antimalarial plants in Kenya based on electronic data. A comprehensive web search was conducted in multidisciplinary databases, and a total of 286 plant species from 75 families, distributed among 192 genera, were retrieved. Globally, about 139 (48.6%) of the species have been investigated for antiplasmodial (18%) or antimalarial activities (97.1%) with promising results. However, there is no record on the antimalarial activity of about 51.4% of the species used although they could be potential sources of antimalarial remedies. Analysis of ethnomedicinal recipes indicated that mainly leaves (27.7%) and roots (19.4%) of shrubs (33.2%), trees (30.1%), and herbs (29.7%) are used for preparation of antimalarial decoctions (70.5%) and infusions (5.4%) in Kenya. The study highlighted a rich diversity of indigenous antimalarial plants with equally divergent herbal remedy preparation and use pattern. Further research is required to validate the therapeutic potential of antimalarial compounds from the unstudied claimed species. Although some species were investigated for their antimalarial efficacies, their toxicity and safety aspects need to be further investigated.

1. Introduction

Globally, malaria continues to be in the top list of the major global health challenges. A global estimate of 655,000 malarial deaths was reported in 2010 of which 91% were in Africa and 86% of these were children under 5 years of age [1, 2]. Africa is particularly more susceptible, and conservative estimates cited that malaria causes up to 2 million deaths annually in Africa [3, 4]. The World Health Organization reported that about 2 billion people in over 100 countries are exposed to malaria, and the situation is exacerbated on the African continent which is characterized by limited access to health services and chronic poverty [5]. In East Africa and Kenya particularly, malaria remains endemic in the Lake Victoria basin and the coast with the country's highest rate of infection at 27% (6 million cases) in 2015 from 38% in 2010 [6, 7]. The Kenyan population at risk of malaria as of 2016 was estimated at 100% [5]. Anopheles gambiae and A. funestus are the primary vectors of malaria in East Africa [8], while Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax are the deadliest malarial parasites in sub-Saharan Africa.

The misuse of chloroquine in the management of malaria has led to the development of chloroquine-resistant parasites worldwide [9]. In Kenya, the use of chloroquine has been discontinued as the first line treatment for malaria due to the prevalence of resistant P. falciparum strains [10, 11]. Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is currently the only available treatment option for malaria as the quinolines (quinine, chloroquine, and mefloquine) have been reported to cause cardiotoxicity, and the malarial parasites have already developed sturdy resistance to them [12, 13]. Unfortunately, resistance of P. falciparum to artemisinin has also been reported elsewhere [14].

The Kenyan government has attempted to reduce malaria incidences in Kenya through several approaches including entomologic monitoring, insecticide resistance management, encouraging the population to sleep under insecticide-treated mosquito nets, intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women, and indoor residual spraying [6, 7, 15, 16]. The situation has been made more complicated by the emergence of pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes throughout Western Kenya which prompted the government to declare no spraying of mosquitoes between 2013 and 2016 [6].

Malaria may manifest with relatively simple symptoms such as nausea, headache, fatigue, muscle ache, abdominal discomfort, and sweating usually accompanied by high fever [17]. However, at advanced stages, it can result in serious complications such as kidney failure, pulmonary oedema, brain tissue injury, severe anaemia, and skin discoloration [5, 18]. Conventional treatment is usually costly, and in rural Kenya just like in other parts of the world, the use of plants for either preventing or treating malaria is a common practice [3]. The current study attempted to gather comprehensive ethnobotanical information on various antimalarial plants and their use in Kenyan communities to identify which plants require further evaluation for their efficacy and safety in malaria management.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Relevant literature pertaining to antimalarial plants and their use in management of malaria and malarial symptoms in Kenya were sourced from Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Scientific Electronic Library Online from November 2019 to February 2020 following procedures previously used [19–21]. The searches were performed independently in all the databases. Key search words such as malaria, vegetal, traditional medicine, ethnobotany, alternative medicine, ethnopharmacology, antimalarial, quinine, chloroquine, antimalarial activity, antiplasmodial activity, malaria management, and Kenya were used. All publishing years were considered, and reports with information on antimalarial or medicinal plants in Kenya were carefully screened. Thus, references contained within the returned scientometric results were assessed concerning their inclusion in the study, and further searches were carried out at the Google search engine using more general search terms, to broaden the search, as follows: words: malaria, plants, plant extract, vegetal, vegetal species, vegetal extract, traditional medicine, alternative medicine, complementary therapy, natural medicine, ethnopharmacology, ethnobotany, herbal medicine, herb, herbs, decoction, infusion, macerate, concoction, malaria fever, malaria incidence, and Kenya were used. The last search was done on 15th February 2020. The search outputs were saved wherever possible on databases, and the author received notification of any new searches meeting the search criteria from Science Direct, Scopus, and Google scholar. For this study, only full-text original research articles published in peer-reviewed journals, books, theses, dissertations, patents, and reports on antimalarial plants or malaria phytotherapy in Kenya written in English and dated until February 2020 were considered.

Missing information in some studies particularly the local names, growth habit of the plants, and misspelled botanical names were retrieved from botanical databases: The Plant List, International Plant Names Index, NCBI taxonomy browser and Tropicos, and the Google search engine. Where a given species was considered as distinct species in different reports, the nomenclature as per the botanical databases took precedence. The traditional perception of malaria as well as the families, local names (Digo, Giriama, Kamba, Kikuyu, Kipsigis, Kuria, Luo, Markweta, Maasai, Nandi, and Swahili), growth habit, part (s) used, preparation, and administration mode of the different antimalarial plants were captured.

2.2. Data Analysis

All data were entered into Microsoft Excel 365 (Microsoft Corporation, USA). Descriptive statistical methods, percentages, and frequencies were used to analyze ethnobotanical data on reported medicinal plants and associated indigenous knowledge. The results were subsequently presented as tables and charts.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Antimalarial Plants Used in Kenya

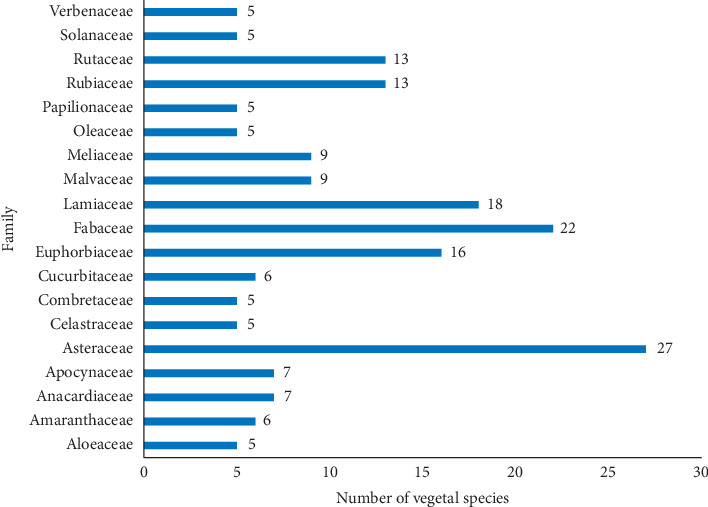

In aggregate, 61 studies and reports identified 286 plant species from different regions of Kenya belonging to 75 botanical families distributed among 192 genera (Table 1). Asteraceae (36.5%), Fabaceae (29.7%), Lamiaceae (24.3%), Euphorbiaceae (21.6%), Rutaceae (17.6%), and Rubiaceae (17.6%) were the most common plant families (Figure 1). The most frequently encountered species were Toddalia asiatica (L.) Lam (11 times), Aloe secundiflora Engl. (10 times), Azadirachta indica A. Juss, Carissa edulis (Forsk.) Vahl., Harrisonia abyssinica Olive (9 times each), Zanthoxylum chalybeum Engl. (8 times), Ajuga remota Benth., Rotheca myricoides (Hochst.) Steane and Mabb, Warburgia ugandensis Sprague (7 times each), Albizia gummifera (J. F. Gmel.), Erythrina abyssinica Lam. ex DC., Plectranthus barbatus Andrews, Rhamnus prinoides L.'Herit, Senna didymobotrya (Fresen) Irwin and Barneby, and Solanum incanum L. (6 times). One botanically unidentified plant (Ima) was reported by Kuria et al. [11]. Decoction of a whole lichenized fungi (Usnea species and Intanasoito in Maasai dialect) and Engleromyces goetzei P. Henn. fungi were also reported to be used in management of malaria in rural Kenya [22, 23].

Table 1.

Synopsis of medicinal plants used in the management of malaria in Kenya.

| Plant family | Botanical name | Local name | Part(s) used | Habit | Preparation mode | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Justicia betonica L. | Shikuduli | Aerial parts | Herb | Decoction | [34, 35] |

|

| ||||||

| Alliaceae | Allium sativum L. | Kitungu saumu (Luo) | Roots | Herb | Crushed, chewed | [36] |

|

| ||||||

| Aloeaceae | Aloe barbadensis Mill. (vera) | Oldopai (Maasai) | Leaves | Herb | Not specified | [37] |

| Aloe kedongensis Reynolds | Osukuroi (Maasai) | Leaves, roots | Herb | Infusion | [3, 38–40] | |

| Aloe elgonica Bullock | Not reported | Leaves, roots | Herb | Decoction | [41] | |

| Aloe lateritia Engl. | Kiiruma (Kikuyu) | Leaves, root | Herb | Decoction | [3, 42] | |

| Aloe volkensii Engl. | Osukuroi (Maasai) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [22] | |

| Caesalpinia volkensii Harms | Mujuthi (Kikuyu) | Leaves | Liana | Decoction | [3, 11, 43, 44] | |

|

| ||||||

| Amaranthaceae | Achyranthes aspera L. | Uthekethe (Kamba) | Whole plant | Herb | Not specified | [23, 45] |

| Amaranthus hybridus L. | Mchicha (Swahili) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [17, 46] | |

| Celosia schweinfurthiana Schinz. | Not reported | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [47] | |

| Cyathula schimperiana non Moq | Namgwet | Leaves, roots | Herb | Decoction | [38, 40] | |

| Cyathula cylindrica Moq | Ng'atumyat | Roots | Herb | Decoction | [38, 40] | |

| Sericocomopsis hildebrandtii Schinz. | Oloituruj-ilpeles (Maasai) | Roots | Shrub | Decoction | [22, 48] | |

|

| ||||||

| Anacardiaceae | Heeria insignis Del. | Mwamadzi (Swahili) | Bark, stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [17, 46] |

| Lannea schweinfurthii (Engl.) Engl. | Mnyumbu | Bark, leaves | Shrub | Not specified | [49, 50] | |

| Ozoroa insignis Delile | Not reported | Not reported | Shrub | Not specified | [42] | |

| Rhus natalensis Bernh. ex Krauss | Muthigiu (Kikuyu) | Root, stem, fruits, root bark | Tree | Decoction | [3, 42, 49–51] | |

| Rhus vulgaris Meikle | Sungula | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [3, 42] | |

| Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rixh.) Hochst | Oloisuki (Maasai) | Bark | Tree | Not specified | [49] | |

| Searsia natalensis (Bernh. ex C. Krauss) | Olmisigiyioi (Maasai) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [34] | |

|

| ||||||

| Annonaceae | Uvaria acuminata Oliv. | Mukukuma (Kamba) | Roots | Shrub | Not specified | [50] |

| Uvaria scheffleri Diels | Not reported | Leaves | Liana | Decoction | [17] | |

| Apiaceae | Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. | Not reported | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [17] |

|

| ||||||

| Apocynaceae | Carissa edulis (Forssk.) Vahl. | Olamuriaki (Maasai), Mukawa (Kikuyu) | Root, root bark | Shrub | Decoction, inhale steam | [3, 17, 34, 38, 40, 47, 48, 52, 53] |

| Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don | Olubinu | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [47] | |

| Gomphocarpus fruticosus (L.) W. T. Aiton | Kosirich | Root | Herb | Not specified | [54] | |

| Laudolphia buchananii (Hall.f) Stapf | Mhonga (Swahili) | Leaves | Liana | Decoction | [17, 46] | |

| Mondia whitei | Ogombo (Luo) | Roots | Herb | Chewed | [42] | |

| Rauwolfia cothen | Not reported | Root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [17] | |

| Saba comorensis (Bojer ex A.D.C) Pichon | Abuno (Luo) | Not specified | Herb | Not reported | [42] | |

|

| ||||||

| Asclepiadaceae | Curroria volubilis (Schltr.) Bullock | Simatwet | Bark | Liana | Decoction | [38, 40] |

| Periploca linearifolia Dill. & A. Rich. | Muimbathunu (Kikuyu) | Bark | Liana | Decoction | [3, 44] | |

|

| ||||||

| Asteraceae | Achyrothalamus marginatus O. Hoffm. | Not reported | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [55] |

| Acmella caulirhiza Del. | Shituti | Aerial parts | Shrub | Decoction | [34, 56] | |

| Ageratum conyzoides L. | Not reported | Whole plant | Herb | Decoction | [56, 57] | |

| Artemisia afra Jacq | Not reported | Leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [41] | |

| Artemisia annua L. | Not reported | Leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [42] | |

| Aspilia pluriseta Schweinf. | Rirangera | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [35] | |

| Bidens pilosa L. | Nyanyiek mon (Luo) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [11, 37] | |

| Ethulia scheffleri S. Moore | Not reported | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [58] | |

| Gutenbergia cordifolia Benth. | Olmiakaru-kewon (Maasai) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [48] | |

| Kleinia squarrosa | Mungendya (Kamba) | Leaves | Shrub | Infusion | [55] | |

| Launaea cornuta (Oliv and Hiern) C. Jeffrey | Uthunga (Kamba) | Leaves | Liana | Infusion/decoction | [17, 46, 55] | |

| Microglossa pyrifolia (Lam.) O. Kuntze | Nyabung-Odide (Luo) | Root, leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [34, 37, 38] | |

| Psiadia arabica Jaub. & Pach | Nyabende winy (Luo) | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [42] | |

| Psiadia punctulata (D.C.) Vatke | Olobai (Maasai) | Roots | Herb | Not specified | [48] | |

| Sonchus schweinfurthii Oliv. & Hiern | Egesemi (Kuria) | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [37] | |

| Schkuhria pinnata (Lam.) Kuntze ex Thell | Gakuinini (Kikuyu) | Whole plant | Herb | Infusion | [3, 23, 42, 44] | |

| Senecio syringitolia O. Hoffman | Reisa (Digo) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [17, 46] | |

| Solanecio mannii (Hook. f) C. Jeffrey | Maroo, marowo (Luo), Livokho | Leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [23] | |

| Sonchus luxurians (R.E. Fries) C. Jeffrey | Kimogit (Nandi) | Roots | Herb | Decoction | [38] | |

| Sphaeranthus suaveolens (Forsk.) DC | Njogu-ya-iria | Whole plant | Herb | Infusion, rubbed on the body | [44, 52] | |

| Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) Gray | Maua madongo (Luo) | Leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 34, 42] | |

| Tridax procumbens L. | Not reported | Whole plant | Herb | Infusion | [17] | |

| Vernonia amygdalina Del. | Musulilitsa | Leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 34, 42] | |

| Vernonia auriculifera (Welw.) Hiern | Muthakwa | Leaves, roots, bark | Shrub | Infusion, decoction | [35, 37, 38, 41, 44] | |

| Vernonia brachycalyx O. Hoffm. Schreber | Irisabakw (Kuria) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [37, 44, 58] | |

| Vernonia brachycalyx O. Hoffm. Lasiopa Lam. | Olusia (Luo) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [37] | |

| Vernonia lasiopus O. Hoffm. | Shiroho, Mwatha | Leaves, root bark | Shrub | Infusion | [23, 35, 44] | |

|

| ||||||

| Bignoniaceae | Kigelia africana (Lamk.) Benth. | Omurabe, Morabe | Leaves, bark, fruits | Tree | Decoction | [44, 58, 59] |

| Markhamia lutea (Benth.) K. Schum. | Lusiola, Shisimbali | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [34, 47] | |

| Markhamia platycalyx Sprague | Siala (Luo) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [42] | |

| Spathodea campanulata P. Beauv. | Muthulio, Mutsuria | Leaves | Tree | Decoction | [34] | |

|

| ||||||

| Boraginaceae | Ehretia cymosa Thonn | Mororwet | Leaves, roots | Shrub | Infusion | [38, 40] |

|

| ||||||

| Burseraceae | Commiphora eminii Engl | Mukungugu (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [3] |

| Commiphora schimperi (Berg) Engl. | Osilalei (Maasai), Dzongodzongo (Swahili) | Inner bark, roots, stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [17, 46, 48] | |

|

| ||||||

| Canellaceae | Warburgia salutaris (Bertol.F.) Chiov. | Osokonoi (Maasai) | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [22, 37, 45] |

| Warburgia stuhlmannii Engl. | Not reported | Stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [17] | |

| Warburgia ugandensis Sprague subsp ugandensis | Muthiga (Kikuyu) | Stem bark, fruits, leaves | Tree | Decoction | [3, 11, 22, 34, 43, 51, 54] | |

|

| ||||||

| Capparaceae | Boscia angustifolia A. Rich. | Oloiroroi (Maasai) | Inner bark fibres, stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [42, 44, 48, 52] |

| Boscia salicifolia Oliv. | Mwenzenze (Kamba) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [49] | |

| Cadaba farinosa Forssk | Akado marateng (Luo) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [42] | |

| Capparidaceae | Cleome gynandra L. | Isakiat | Leaves, roots | Herb | Decoction | [40] |

| Cariaceae | Carica papaya L. | Poipoi, Apoi (Luo) | Leaves, roots, sap | Shrub | Infusion, decoction | [36] |

|

| ||||||

| Celastraceae | Maytenus arbutifolia (A. Rich.) Wilczek | Muraga | Root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [44] |

| Maytenus heterophylla (Eckl. & Zeyh.) N. Robson | Muraga | Root, root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [41, 44] | |

| Maytenus putterlickioides (Loes.) Excell & Mendonca | Muthuthi | Root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [44] | |

| Maytenus senegalensis (Lam.) Exell | Muthuthi (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [3, 47] | |

| Maytenus undata (Thunb.) Blakelock | Muthithioi | Root bark, leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [44] | |

|

| ||||||

| Cleomaceae | Cleome gynandra L. | Isakiat | Leaves roots | Herb | Decoction | [38] |

|

| ||||||

| Combretaceae | Combretum illairii Engl. | Mshinda arume | Leaves, root bark | Tree | Decoction | [50] |

| Combretum molle G. Don | Muama, Kiama (Kamba) | Bark, leaves | Tree | Decoction | [17, 45] | |

| Combretum padoides Engl. & Diels | Mshinda arume | Leaves, roots | Tree | Decoction | [17, 46, 50, 60] | |

| Terminalia brownii Fresen. | Muuku (Kamba) | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [55] | |

| Terminalia spinosa Engl. | Not reported | Bark, stem bark | Tree | Decoction, infusion | [17, 61] | |

|

| ||||||

| Commelinaceae | Aneilema spekei (C. B. Clarke) | Enkaiteteyiai (Maasai) | Whole plant | Liana | Decoction | [22] |

| Commelina forskaolii Vah | Not reported | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [47] | |

|

| ||||||

| Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe lanceolata (Forsk.) Pers. | Mahuithia (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [3] |

|

| ||||||

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucumis aculeatus Cogn. | Gakungui (Kikuyu) | Leaves | Climber | Decoction | [3, 34, 42, 62] |

| Cucumis prophetarum L. | Chepsawoy (Kipsigis) | Root tuber | Herb | Decoction | [39] | |

| Gerranthus lobatus (Cogn.) Jeffrey | Mgore manga (Digo) | Leaves, roots | Herb | Decoction | [17, 46] | |

| Momordica foetida Schumach | Cheptenderet (Kipsigis) | Leaves, roots | Liana | Decoction, roasting | [17, 38, 41] | |

| Momordica friesiorum Hams C. Jeffrey | Libobola | Root tuber | Herb | Decoction | [54] | |

| Zehneria minutiflora (Cogn.) C. Jeffrey | Manereriat (Kimanererit) | Leaves, roots | Liana | Decoction | [38] | |

|

| ||||||

| Cyperaceae | Cyperus articulatus L. | Ndago | Tuber | Herb | Infusion | [44] |

|

| ||||||

| Ebenaceae | Euclea divinorum Hiern | Uswet (Markweta) | Root bark | Tree | Decoction, use for brushing teeth | [38, 47] |

| Diospyros abyssinica (Hiern) F. White subsp. abyssinica | Lusui | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [41, 59] | |

| Diospyros scabra | Not reported | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [61] | |

|

| ||||||

| Euphorbiaceae | Bridelia micrantha Baill. (Hochst). | Mdungu (Digo) | Leaves, bark, stem bark | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 46] |

| Clutia abyssinica Jaub. & Spach | Muthima mburi (Kikuyu) | Leaves, root, root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 38, 44] | |

| Croton dichogamus Pax. | Oloiborrbenek (Maasai) | Whole plant | Shrub | Decoction | [22, 38] | |

| Croton macrostachyus Hochst. ex Del. | Mukinduri (Kikuyu) | Leaves, root, bark | Tree | Decoction | [34, 38, 56] | |

| Croton megalocarpoides Friis & M.G. Gilbert | Ormegweit (Maasai) | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [22] | |

| Croton megalocarpus Del. | Not reported | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [3] | |

| Euphorbia inaequilatera Sond. | Ogota Kwembeba | Whole plant | Shrub | Decoction | [35] | |

| Euphorbia meridionalis Bally & S. Carter | Enkokuruoi (Maasai) | Stem | Climber | Not specified | [22] | |

| Euphorbia tirucalli L. | Kariria (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [3] | |

| Flueggea virosa (Willd.) Voigt | Mukwamba | Root bark | Tree | Decoction | [50] | |

| Flueggea virosa (Roxb.ex Willd.) Royle | Mkwamba, mteja (Swahili) | Aerial parts, root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 34] | |

| Neoboutonia macrocalyx Pax | Mutuntuki | Leaves, stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [44, 53] | |

| Phyllanthus sepialis Müll. Arg. | Not reported | Leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [34] | |

| Ricinus communis L. | Kivaiki (Kamba) | Root, seeds, leaves | Shrub | Decoction, topical | [17, 38, 46] | |

| Sapium ellipticum | Achak (Luo) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [42] | |

| Suregada zanzibariensis Baill | Not reported | Root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [17] | |

|

| ||||||

| Fabaceae | Abrus precatorius L. ssp africanus Verdc | Ndirakalu | Leaves | Herb | Not specified | [42, 50] |

| Acacia hockii De Wild. | Eluai (Maasai) | Root bark | Tree | Decoction | [48] | |

| Acacia mellifera (M.Vahl) Benth. | Oiti (Maasai), Muthiia (Kamba) | Stem bark, root, pith | Tree | Decoction | [11, 22, 48, 52, 63] | |

| Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd.ex Delile | Olkirorit, Ol-rai (Masaai) | Bark, root | Tree | Decoction | [22, 37, 53, 64] | |

| Acacia oerfota (Forssk.) Schweinf. | Not reported | Root | Tree | Not reported | [63] | |

| Acacia seyal Delile | Mgunga (Digo) | Root | Tree | Decoction | [17] | |

| Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Hayne | Oltepesi (Maasai) | Sap, roots | Tree | Taken directly, decoction | [22, 48] | |

| Albizia amara (Roxb.) Boiv. | Mwiradathi | Stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [44] | |

| Albizia anthelmintica Brongn. | Kyoa (Kamba) | Root, bark | Tree | Decoction | [17, 22, 63] | |

| Albizia coriaria Welw ex Oliver | Omubeli | Multiple parts | Tree | Decoction | [42, 47, 57, 65] | |

| Albizia gummifera (J.F. Gmel.) | Seet (Nandi) | Root, stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [23, 34, 38, 42, 44, 66] | |

| Albizia zygia (DC) J.F. Macbr. | Ekegonchori (Kuria) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [37] | |

| Cassia didymobotrya Fres. | Irebeni (Kuria), Murao | Leaves, roots, root bark | Shrub | Infusion, decoction | [37, 38, 40, 44] | |

| Cassia occidentalis L. | Mnuka uvundo (Swahili) | Leaves, roots | Herb | Decoction | [11, 17, 46] | |

| Dichrostachys cinereal L. | Chinjiri (Digo) | roots | Tree | Decoction | [17] | |

| Erythrina abyssinica Lam. ex DC. | Omutembe (Kuria), Muhuti (Kikuyu) | Root, bark | Tree | Decoction | [3, 23, 34, 37, 38, 42] | |

| Indigofera arrecta A. Rich | Not reported | Roots | Herb | Decoction, chew directly | [41] | |

| Mucuna gigantea | Ogombo (Luo) | Not specified | Liana | Not specified | [42] | |

| Senna didymobotrya (Fresen) Irwin & Barneby | Osenetoi (Maasai) | Roots, leaves, bark, stem | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 23, 34, 41, 42, 67] | |

| Senna occidentalis (L.) Link | Imbindi | Roots | Shrub | Decoction | [34, 47] | |

| Tamarindus indica L. | Muthumula (Kamba), Mkwadzu (Swahili) | Bark, fruits, roots, leaves | Tree | Decoction, fruit eaten | [17, 46, 47, 54] | |

| Tylosema fassoglense | Not reported | Tuber | Climber | Not specified | [56] | |

|

| ||||||

| Hydnoraceae | Hydnora abyssinica Schweinf. | Muthigira (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [3] |

|

| ||||||

| Hypericaceae | Harungana madagascariensis Lam. ex Poir. | Musila | Stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [17, 34, 42] |

|

| ||||||

| Icacinaceae | Pyrenacantha malvifolia Engl. | Empalua (Maasai) | Roots | Climber | Not specified | [22] |

|

| ||||||

| Lamiaceae | Ajuga integrifolia Buch. Ham. | Imbuli yumtakha | Aerial parts | Herb | Decoction | [34] |

| Ajuga remota Benth. | Wanjiru (Kikuyu) | Leaves, roots, whole plant | Herb | Decoction | [3, 11, 23, 38, 44, 68, 69] | |

| Clerodendrum johnstonii Oliv | Singoruet (Nandi) | Leaves | Shrub | Infusion | [34, 38] | |

| Fuerstia africana T.C.E.Fr. | Kwa matsai, aremo (Luo) | Aerial parts, leaves, whole plant | Herb | Decoction, infusion | [34, 38, 44, 48, 65] | |

| Hoslundia opposita Vahl. | Cheroronit, Cherungut (Nandi) | Leaves, whole plant | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 38, 46, 50] | |

| Leucas calostachys Oliv | Bware (Luo), Lumetsani | Leaves, roots, aerial parts | Shrub | Decoction | [34, 37, 38] | |

| Leucas martinicensis (Jacq.) Ait.f. | Chepkari (Nandi) | Flowers | Herb | Infusion | [38] | |

| Leonotis mollissima Guerke | Nyanyondhi (Luo), Orbibi (Maasai) | Leaves, roots | Shrub | Decoction | [23, 37, 38] | |

| Leonotis nepetifolia (R. Br) Ait.f. | Kipchuchuniet (Kipsigis) | Not specified | Shrub | Decoction | [47, 70] | |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Sisiyat (Nandi) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [23, 46] | |

| Ocimum balansae Briq. | Not reported | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [17] | |

| Ocimum gratissimum L. Suave wiild, O. tomentosum Oliv. | Mukandu (Kamba) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [17, 23] | |

| Ocimum kilimandscharicum Guerke | Mutaa (Kamba) | Aerial parts | Herb | Inhale steam | [3, 34, 56] | |

| Ocimum lamiifolium Benth | Not reported | Roots | Shrub | Decoction | [38] | |

| Ocimum suave Willd | Murihani (Giriama) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [17, 46, 71] | |

| Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | Kan'gurwet (Markweta) | Leaves | Shrub | Infusion, decoction | [17, 34, 42, 46, 56, 58] | |

| Plectranthus sylvestris Gurke | Not reported | Leaves | Herb | Not specified | [58] | |

| Rotheca myricoides (Hochst.) Steane and Mabb (Clerodendrum myricoides (Hochst.) Vatke) | Olmakutukut (Maasai), Munjuga iria (Kikuyu) | Roots, leaves, root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 34, 38, 42, 44, 48, 67] | |

|

| ||||||

| Lauraceae | Ocotea usambarensis Engl. | Muthaiti (Kikuyu) | Root bark | Tree | Infusion | [3, 44] |

|

| ||||||

| Loganiaceae | Strychnos henningsii Gilg | Muteta (Kamba, Kikuyu) | Roots, leaves, stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [3, 11, 44, 47, 55, 67] |

|

| ||||||

| Malvaceae | Adansonia digitata L. | Mbamburi (Swahili) | Leaves | Tree | Decoction | [17, 46] |

| Azanza gackeana (F. Hoffm.) Excell & Hillcoat | Mutoo (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [3] | |

| Grewia bicolor Juss | Esiteti (Maasai) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [47] | |

| Grewia hainesiana Hole | Not reported | Leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [17] | |

| Grewia hexamita Burret | Mkone (Digo) | Roots, leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [46] | |

| Grewia plagiophylla K. Schum | Mkone (Digo) | Bark, leaves | Not specified | [50] | ||

| Grewia trichocarpa (Hochst) ex A. Rich. | Cone (Digo) | Roots | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 41, 46] | |

| Pavonia kilimandscharica Gurke | Chemanjililiet, Chepsabuni (Nandi) | Roots | Herb | Decoction | [38] | |

| Sida cordifolia L. | Menjeiwet (Nandi) | Leaves | Shrub | Infusion | [38] | |

| Meliaceae | Azadirachta indica A. Juss | Muarubaini (Kamba) | Leaves, roots, bark | Tree | Decoction, inhalation, topical | [3, 11, 17, 36, 43, 50, 54, 55, 72] |

| Azadirachta indica (L) Burm. | Mkilifi (Digo) | Leaves, roots, root bark | Tree | Decoction | [46, 73] | |

| Ekebergia capensis Sparrm. | Olperre-longo (Maasai) | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [3, 48] | |

| Melia azedarach L. | Mwarubaine | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [47] | |

| Melia volkensii L. | Mukau (Kamba) | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [55] | |

| Melia azedarach L. | Mwarubaini (Nandi) | Leaves, bark | Tree | Decoction | [34, 38, 42] | |

| Trichilia emetica Vahl. | Munyama | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [34, 72] | |

| Turraea mombassana C. DC | Onchani Orok (Maasai) | Leaves, root, fruits | Shrub | Decoction | [67] | |

| Turraea robusta | Not reported | Root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [49] | |

|

| ||||||

| Melianthaceae | Bersama abyssinica Fres. | Kibuimetiet (Nandi) | Root bark, bark, seeds | Tree | Decoction | [38, 41] |

|

| ||||||

| Menispermaceae | Cissampelos mucronata A. Rich. | Mukoye | Root | Climber | Root chewed | [17, 34, 74, 75] |

| Cissampelos pareira L. | Karigi munana | Root, root bark | Liana | Decoction | [39] | |

|

| ||||||

| Moraceae | Ficus bussei Warb ex Mildbr and Burret | Mgandi (Digo) | Roots, leaves | Tree | Decoction | [17, 46] |

| Ficus cordata Thunb | Oladardar (Maasai) | Branches, roots, stem | Tree | Decoction | [67] | |

| Ficus sur. Forssk | Omora | Stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [35] | |

| Ficus thonningii Blume | Mutoto | Stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [34] | |

|

| ||||||

| Myricaceae | Myrica salicifolia A. Rich. | Murima | Root bark | Tree | Decoction | [44] |

|

| ||||||

| Myrsinaceae | Embelia schimperi Vatke | Kibong'ong'inik (Nandi) | Seeds | Tree | Decoction | [38] |

| Maesa lanceolata Forssk | Katera (Luo), Kibabustanyiet (Nandi) | Roots, fruits, seeds, bark | Shrub | Decoction | [22, 34, 38, 76] | |

|

| ||||||

| Myrtaceae | Eucalyptus globulus Labil. | Mubau (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [3] |

| Psidium guajava L. | Mapera (Luo) | Leaves, fruits | Tree | Decoction | [36] | |

|

| ||||||

| Oleaceae | Jasminum floribunda R.Br. | Not reported | Root | Herb | Decoction | [41] |

| Jasminum fluminense Vell. | Kipkoburo | Bark, stem, root tuber | Vine | Not specified | [77] | |

| Olea capensis L. | Mutukhuyu, Mucharage | Stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [41, 44] | |

| Olea europaea L. | Oloirien (Maasai) | Inner/stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [3, 22, 44, 45, 48] | |

| Ximenia americana L. | Olamai (Maasai) | Leaves | Tree | Decoction | [47] | |

|

| ||||||

| Onagraceae | Ludwigia erecta (L.) Hara | Mungei | Whole plant | Herb | Infusion, decoction | [44, 52] |

|

| ||||||

| Opiliaceae | Opilia campestris Engl. | Enkirashai (Maasai) | Roots | Shrub | Decoction | [22] |

|

| ||||||

| Oxalidaceae | Oxalis corniculata L. | Nyonyoek (Nandi) | Whole plant | Herb | Decoction | [38] |

|

| ||||||

| Papilionaceae | Cajanus cajan Millsp. | Mucugu (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [3] |

| Dalbergia lactea Vatke | Mwaritha (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [3] | |

| Ormocarpum trachycarpum (Taub.) Harms | Muthingii (Kamba) | Bark, leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [52, 58] | |

| Rhynchosia hirta (Andrews) Meikle & Verdc. | Tilyamook (Nandi) | Roots | Liana | Decoction | [38] | |

| Stylosanthes fruticosa (Retz.) Alston | Kalaa (Kamba) | Leaves, whole plant | Herb | Infusion | [55] | |

|

| ||||||

| Passifloraceae | Passiflora ligularis A. Juss. | Hondo (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [3] |

|

| ||||||

| Piperaceae | Piper capense L.f. | Olerrubaat (Maasai) | Roots | Herb | Decoction | [48] |

|

| ||||||

| Pittosporaceae | Pittosporum lanatum Hutch. & Bruce | Munyamati (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [3] |

| Pittosporum viridiflorum Sims | Munati | Stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [34, 44, 52] | |

|

| ||||||

| Poaceae | Pennisetum hohenackeri Hochst. ex Steud | Olmakutian (Maasai) | Bark, branches, roots | Grass | Decoction | [67] |

| Rottboellia exaltata L.f. | Mpunga (Digo) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [17, 46] | |

| Sporobolus stapfianus | Not reported | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [45] | |

|

| ||||||

| Podocarpaceae | Podocarpus latifolius (Thunb.) R.Br. ex Mirb. | Enchani-enkashi (Maasai) | Roots | Tree | Decoction | [48] |

|

| ||||||

| Polygonaceae | Rumex abyssinicus Jacq. | Shikachi | Leaves | Herb | Decoction | [34] |

| Rumex steudelii Hochst ex A. Rich | Alukhava | Roots | Herb | Decoction | [34] | |

|

| ||||||

| Polygalaceae | Securidaca longifolia Poepp. | Not reported | Roots | Tree | Decoction | [17] |

| Securidaca longipedunculata Fres. | Mzigi (Digo) | Roots, bark, leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [46] | |

|

| ||||||

| Primulaceae | Myrsine africana L. | Oseketeki (Maasai) | Seeds, fruits, roots, multiple parts | Shrub | Decoction | [54, 67] |

|

| ||||||

| Rahmnaceae | Rhamnus prinoides L.'Herit | Orkonyil (Maasai) | Roots, root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 11, 35, 38, 44, 48, 69, 78] |

| Rhamnus staddo A. Rich | Orkokola (Maasai), Ngukura (Kikuyu) | Root bark, stem bark | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 11, 35, 44, 48, 69] | |

| Scutia myrtina (Burm. f.) Kurz | Osanankoruri (Maasai) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [3] | |

|

| ||||||

| Ranunculaceae | Clematis brachiata Thunb. | Olkisusheeit (Maasai) | Roots, root bark | Liana | Decoction | [44, 48] |

|

| ||||||

| Rhizophoraceae | Cassipourea malosana (Baker) Alston | Muthathi (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [3] |

|

| ||||||

| Rosaceae | Prunus africana (Hook. f.) Kalkman | Orkujuk (Maasai), Muiri (Kikuyu) | Bark, root, stem, stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [3, 38, 44, 79, 80] |

| Rubus pinnatus Wild. | Butunduli | Leaves, bark, fruits | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 34] | |

|

| ||||||

| Rubiaceae | Aganthesanthemum bojeri Klotzsch. | Kahithima | Whole plant | Herb | Not specified | [50] |

| Agathisanthenum globosum (Hochst. ex A. Rich.) Bremek. | Chivuma nyuchi (Digo) | Roots | Herb | Decoction | [17, 46] | |

| Canthium glaucum Hiern. | Mhonga/Mronga (Digo) | Fruits | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 46] | |

| Gardenia ternifolia subsp. Jovistonatis | Kibulwa | Fruits | Shrub | Decoction | [54] | |

| Keetia gueinzii (Sond.) Bridson | Mugukuma (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [3] | |

| Pentanisia ouranogyne S. Moore | Chungu (Digo) | Roots | Herb | Decoction | [17, 46] | |

| Pentas bussei K. Krause | Not reported | Root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [17] | |

| Pentas longiflora Oliv. | Muhuha (Kikuyu), Cheroriet (Nandi) | Bark, fruits, leaves, roots | Shrub | Decoction, rub on skin | [3, 17, 38, 41, 61] | |

| Pentas lanceolata (Forssk.) Deflers | Olkilaki-olkerr (Maasai) | Root bark | Herb | Decoction | [48] | |

| Rubia cordifolia L. | Urumurwa (Kuria) | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [37] | |

| Spermacoce princeae (K. Schum.) Verdc. | Omonhabiebo | Whole plant | Herb | Decoction | [35] | |

|

Vangueria madagascariensis

Gmel (Vangueria acutiloba Robyns) |

Mubiru | Stem bark | Shrub | Decoction | [44] | |

| Vangueria volkensii K.Schum. | Kimoluet (Nandi) | Roots | Shrub | Decoction | [38, 47] | |

|

| ||||||

| Rutaceae | Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | Mutimu (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [3] |

| Citrus limon (L.) Burm.f. | Ndim (Luo) | Fruits, leaves | Tree | Eaten, decoction | [36] | |

| Clausena anisata (Willd) Hook. f. ex Benth. | Mtondombare (Digo), Mukibia | Leaves, roots, bark, root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 34, 41, 44, 46] | |

| Fagaropsis angolensis (Eng.) H.M. Gardner | Murumu, mukuriampungu | Leaves, roots, stem bark | Tree | Decoction | [3, 23, 38, 44, 53] | |

| Fagaropsis angolensis (Eng.) Dale | Mukaragati (Kikuyu) | Leaves, roots | Tree | Decoction | [3, 17, 46] | |

| Fagaropsis hildebrandtii (Engl.) Milne-Redh. | Muvindavindi (Kamba) | Leaves | Tree | Decoction | [3, 81] | |

| Harrisonia abyssinica Olive | Osiro (Luo), Orongoriwe (Kuria) | Leaves, roots, root bark | Tree | Decoction | [17, 23, 37, 44, 46, 47, 54, 82, 83] | |

| Teclea nobilis | Not reported | Stem bark | Shrub | Decoction | [11, 45] | |

| Teclea simplicifolia (Engl.) Verdoorn | Mutuiu (Kamba), Munderendu (Kikuyu) | Leaves, roots, stem bark | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 17, 44, 46, 55] | |

| Toddalia asiatica (L.) Lam | Mururue (Kikuyu), Oleparmunyo (Maasai) | Roots, root bark, leaves, fruits (multiple parts) | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 11, 17, 44, 45, 47, 58, 59, 62, 67, 84] | |

| Zanthoxylum chalybeum Engl. | Oloisuki (Maasai) | Stem bark, root bark | Tree | Decoction | [3, 17, 44, 46, 55, 61, 71, 85] | |

| Zanthoxylum gilletii (De Wild.) P.G. Waterman | Shihumba/Shikuma | Bark | Tree | Decoction | [34, 86] | |

| Zanthoxylum usambarense (Engl.) Kokwaro | Oloisuki (Maasai) | Root, fruits, bark, leaves, stem | Tree | Decoction | [3, 11, 67, 78, 85] | |

|

| ||||||

| Salicaceae | Dovyalis abyssinica (A. Rich.) Warb | Kaiyaba (Kikuyu) | Leaves, roots | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 38] |

| Dovyalis caffra (Hook. f. & Harv.) Warb | Mukambura (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [3] | |

| Flacourtia indica (Burm.f) Merr. | Mtondombare (Digo) | Roots, bark | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 46] | |

| Trimeria grandifolia (Hochst.) Warb | Oledat (Maasai) | Roots | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 38, 47] | |

|

| ||||||

| Salvadoraceae | Salvadora persica L. | Mukayau (Kamba) | Root, stem | Shrub | Decoction; prepared with salt and milk | [22, 51, 63] |

|

| ||||||

| Santalaceae | Osyris lanceolata Hochst. & Steudel | Olosesiai (Maasai), muthithii (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [3] |

|

| ||||||

| Sapindaceae | Allophylus pervillei Blume. | Mvundza kondo | Leaves, roots, bark | Shrub | Decoction | [50] |

| Cardiospermum corundum | Not reported | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [23] | |

| Pappea capensis (Spreng) Eckl. & Zeyh. | Muba (Kikuyu), Enkorr irri (Maasai) | Branches | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 48] | |

|

| ||||||

| Sapotaceae | Manilkara butegi | Anon | Bark | Shrub | Decoction | [54] |

| Mimusops bagshawei S. Moore | Lolwet (Nandi) | Leaves, bark | Tree | Decoction | [38] | |

|

| ||||||

| Solanaceae | Physalis peruviana L. | Mayengo | Leaves | Shrub | Inhale steam | [34] |

| Solanum aculeastrum Dunal | Mutura (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Shrub | Not specified | [3] | |

| Solanum incanum L. | Mutongu (Kamba), Entulelei (Maasai) | Roots, leaves, root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [17, 34, 37, 44, 46, 87] | |

| Solanum taitense Vatke | Entemelua (Maasai) | Roots | Shrub | Chewed directly | [22] | |

| Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal | Murumbae (Kikuyu) | Root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 44] | |

|

| ||||||

| Ulmaceae | Chaetacme aristate Planch | Not reported | Roots | Shrub | Decoction | [41] |

|

| ||||||

| Urticaceae | Urtica massaica Mildbr. | Thabai (Kikuyu) | Aerial parts | Herb | Decoction | [3, 35] |

|

| ||||||

| Verbenaceae | Clerodendrum eriophyllum Guerke | Muumba | Root bark | Shrub | Decoction | [44, 52] |

| Lantana camara L. | Ruithiki, Mukenia (Kikuyu) | Leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 73] | |

| Lantana trifolia L. | Ormokongora (Maasai) | Leaves | Shrub | Decoction | [34, 72] | |

| Lippia javanica (Burm.f.) Spreng | Angware-Rao (Luo) | Roots | Herb | Not specified | [37, 58] | |

| Premna chrysoclada (Bojer) Gürke | Mvuma | Roots, leaves | Herb | Not specified | [50] | |

|

| ||||||

| Vitaceae | Cissus quinquangularis L. | Not reported | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [45] |

| Cyphostemma maranguense (Gilg) Desc. | Mutambi (Kikuyu) | Not specified | Herb | Not specified | [3] | |

| Rhoicissus tridentata (L.f.) Wild & Drum | Ndurutua (Kikuyu) | Bark, roots | Shrub | Decoction | [3, 34, 38, 62] | |

|

| ||||||

| Xanthorrhoeaceae | Aloe deserti A. Berger | Ngolonje (Digo) | Leaves | Herb | Decoction, infusion | [17, 46] |

| Aloe macrosiphon Bak. | Golonje (Giriama) | Leaves | Herb | Infusion | [46] | |

| Aloe secundiflora Engl. | Osukuroi (Maasai), Kiluma (Kamba) | Leaves, leaf sap (exudate) | Herb | Infusion, decoction | [11, 17, 34, 43, 44, 46, 58, 78, 88, 89] | |

| Aloe vera (L) Webb. | Alvera (Digo) | Leaves | Herb | Infusion | [17, 46] | |

| Rhoicissus revoilli | Rabongo (Luo) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Zingiberaceae | Zingiber officinale | Tangawizi (Luo) | Roots | Herb | Chewed | [36] |

|

| ||||||

| Zygophyllaceae | Balanites glabrus Mildbr. & Schltr. | Orng'osua (Maasai) | Not specified | Tree | Not specified | [22] |

| Balanites glabra Mildbr. & Schltr. | Olng'osua (Maasai) | Bark | Shrub | Decoction | [22] | |

| Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del. | Olngosua (Maasai) | Bark | Shrub | Decoction | [48] | |

Language is also known as Kikamba. Local names with language(s) not indicated are sometimes a blend of Kiswahili and other local languages or were not specified by the authors. Decoction involves boiling a plant part in water. Infusion entails soaking of a plant part in water.

Figure 1.

Major botanical families from which antimalarial remedies are obtained in Kenya.

Some of the plants such as Acacia mellifera has been reported for treatment of malaria in Somalia [24], Albizia coriaria Welw. ex Oliver, Artemisia annua L., Momordica foetida Schumach, Carica papaya L., and Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don in Uganda [25, 26], Cameroon [27], and Zimbabwe [28], Clematis brachiata and Harrisonia abyssinica Oliv in Tanzania [29] and South Africa [30], Artemisia afra in Ethiopia [31], and Tamarindus indica L., Carica papaya L., and Ocimum basilicum L. in Indonesia [32].

3.2. Growth Habit, Part(s) Used, Preparation, and Administration of Antimalarial Plants

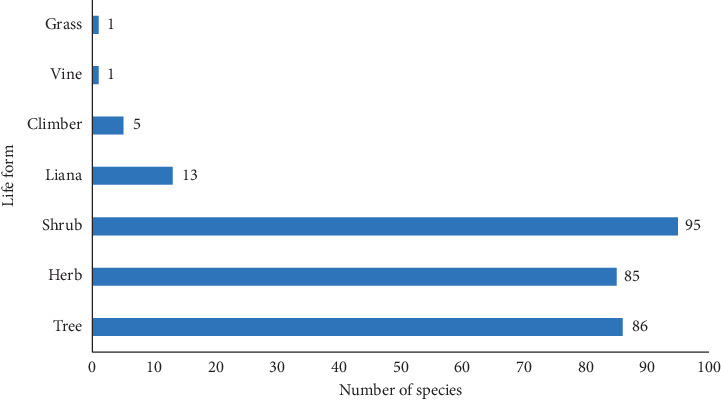

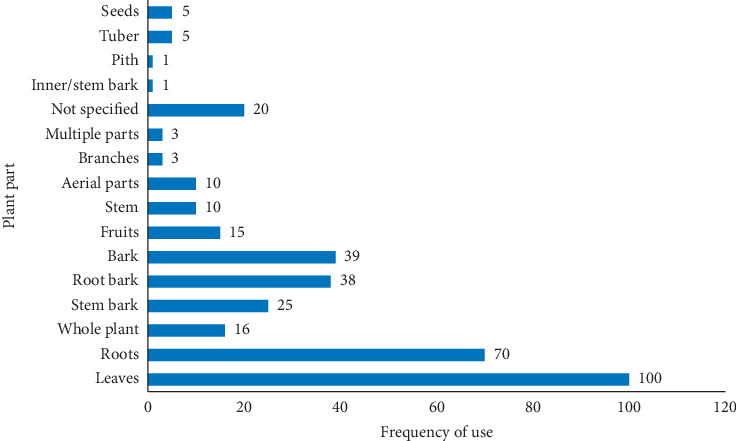

Antimalarial plants used in Kenya are majorly shrubs (33.2%), trees (30.1%), and herbs (29.7%) (Figure 2), and the commonly used plant parts are leaves (27.7%) and roots (19.4%) followed by bark (10.8%), root bark (10.5%), and stem bark (6.9%) (Figure 3). Comparatively, plant parts such as fruits, seeds, buds, bulbs, and flowers which have reputation for accumulating phytochemicals are rarely used, similar to reports from other countries [26, 28, 33].

Figure 2.

Growth habit of antimalarial plants used in Kenyan communities as per ethnobotanical surveys.

Figure 3.

Frequency of the reported plant parts used for preparation of antimalarial remedies in Kenya.

The dominant use of leaves presents little threat to the survival of medicinal plants. This encourages frequent and safe utilization of the plants for herbal preparations. Roots and root structures such as tubers and rhizomes are rich sources of potent bioactive chemical compounds [33], but their frequent use in antimalarial preparations may threaten the survival of the plant species used. For example, Zanthoxylum chalybeum and African wild olive (Olea europaea) have been reported to be threatened due to improper harvesting methods [2]. Thus, proper harvesting strategies and conservation measures are inevitable if sustainable utilization of such medicinal plants are to be realized.

Antimalarial remedies in Kenya are prepared by different methods. These include decoctions (70.5%), infusions (5.4%), ointments and steaming (1.3%), and roasting (0.3%). Preparation of antimalarial remedies from dry parts of one plant or several plants and ashes by using grinding stones was reported [38]. Burning, chewing, heating/roasting, pounding, and boiling or soaking in hot or cold water and milk were reported, and these are then orally administered as is the case with Western medicine [38]. Preparations for application onto the skin such as ointments, poultices, and liniments are frequently percutaneous, by rubbing or covering which are occasionally complimented by massage [38]. Rarely are antimalarial remedies administered through the nasal route. Fresh solid materials are eaten and chewed directly upon collection or after initial pounding/crushing. Dry plant materials are smoked and inhaled. These findings corroborate observations in other countries [33, 90–92].

Malaria is caused by protozoan intracellular haemoparasites, and its treatment entails delivering adequate circulating concentration of appropriate antiprotozoal chemicals. The oral route is a convenient and noninvasive method of systemic treatment as it permits relatively rapid absorption and distribution of active compounds from herbal remedies, enabling the delivery of adequate curative power [93]. In addition, potential risk of enzymatic breakdown and microbial fermentation of active chemical entities may prompt the use of alternative routes of herbal remedy administration like inhalation of the steam or rubbing on the skin.

In this survey, it was noted that few plant species are used for management of malaria simultaneously in different locations. This could probably be attributed to the abundant distribution of the analogue active substances among species, especially belonging to family Asteraceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Meliaceae, Rubiaceae, and Rutaceae. Differences in geographical and climatic conditions may also influence the flora available in a given region. However, some plants have a wider distribution and therefore are used by most communities [34].

3.3. Perception, Prevention, and Treatment of Malaria and Its Symptoms

In rural Kenya, some believe that esse (malaria in native Tugen dialect) is caused by Cheko che makiyo (fresh unboiled milk), dirty water, ikwek (vegetables such as Solanum nigrum and Gynadropis gynadra) [54], mosquito bites, or cold weather [42]. Thus, burning of logs and plants such as Albizia coriaria with cow dung, Azadirachta indica (L) Burm (fresh leaves), Ocimum basilicum L., Ocimum suave Willd. (fresh leaves), and Plectranthus barbatus Andr. (ripe fruits or seeds) are done to keep mosquitoes away [17, 42]. Artemisia annua L. is planted in the home vicinity or near the bedroom window to repel mosquitoes believed to cause malaria [42].

Except in the case of life-threatening illnesses or where there is concern that there may be some supernatural forces in the aetiology of the disease, malaria and its symptoms (periodic fever, sweating, headache, backache, and chills) are treated primarily using decoctions and infusions of plants. Whenever it is thought that malaria is due to supernatural forces, diviners (such as Orgoiyon among the Tugen and Oloiboni among the Maasai) are consulted [94]. Croton dichogamus Pax though used for normal malaria treatment is used by Oloiboni for treatment of malaria or other ailment(s) thought to be due to witchcraft [22]. According to indigenous diagnoses, malaria is due to the presence of excess bile in the body, so the bile has to be expelled before healing can take place. Thus, purgation is regarded as the key treatment regimen for malaria [22, 54].

On the basis of this knowledge, different forms of herbal medications are prescribed according to the severity of the illness. Treatment of malaria is based on a number of interlinked elements: beliefs related to causation, the action or effectiveness of “modern” medicines, and the availability of plant treatments [54]. Salvadora persica L. is used for management of malarial colds, while Aneilema spekei (C. B. Clarke) is used for prevention of malaria fever [22]. The whole plant is mixed with other herbs in milk and sprinkled onto the patient. This is often administered by an Oloibon among the Maasai [22].

Though single plant parts are often used, more than one plant part, for example, decoctions from a mixture of roots of Plectranthus sylvestris together with those of Cassia didymobotrya and Clerodendrum johnstonii may be used as a remedy for malaria and headache [52]. Acacia species stem bark was reported to be used as a first treatment and is usually prepared as an overnight cold-water infusion, and then 40 ml is taken three times a day [11]. A follow-up medication would involve taking a decoction made from powders of Aloe species (leaf juice), Rhamnus staddo (stem or root bark), Clerodendrum myricoides (root bark), Warburgia ugandensis, Teclea nobilis (stem barks), and Caesalpinia volkensii, Ajuga remota Benth, Rhamnus prinoides, and Azadirachta indica leaves [11]. For this, 40 ml is taken thrice a day for 5 days.

The popular method of preparation as decoctions and concoctions suggest that the herbal preparations may only be active in combination, due to synergistic effects of several compounds that are inactive singly [95]. It is possible that some of the compounds that are inactive in vitro could exhibit activity in vivo due to enzymatic transformation into potent prodrugs [96] as reported for Azadirachta indica extracts [97].

3.4. Adverse Side Effects, Antidotes, and Contraindications of Medicinal Plants in Kenya

In traditional context, the pharmacological effect of medicinal plants is generally ascribed to their active and “safe” content that will only exert quick effect when taken in large quantities [22, 33]. Most reviewed reports in this study did not mention the side effects of antimalarial preparations. Nevertheless, herbal preparations from some antimalarial plants were reported to induce vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and urination [22, 54] (Table 2). This may be due to improper dosage, toxic phytochemicals, or metabolic by-products of these preparations [22].

Table 2.

Side effects, antidotes, and contraindications of medicinal plants used for traditional management of malaria in Kenya.

| Plant | Side effects | Antidote(s) | Contraindication | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albizia anthelmintica Brongn. | Induces vomiting, diarrhea, and bile release from the gall bladder | Not reported | Pregnant women | [22] |

| Aloe volkensii L. | Induces vomiting | Not reported | Children | [22] |

| Balanites glabrus Mildbr. & Schltr. | Induces vomiting, diarrhea, and bile release from the gall bladder | Not reported | Pregnant women | [22] |

| Croton megalocarpoides Friis & M.G. Gilbert | Stomachache, induce vomiting, and bile release from the gall bladder | Not reported | Not reported | [22] |

| Euphorbia meridionalis Bally & S. Carter | Induces diarrhea as a means of cleansing the body | Taken with goat or sheep soup | Not reported | [22] |

| Momordica friesiorum Hams C. Jeffrey | Induces vomiting and bile release from the gall bladder | Not reported | Not reported | [54] |

| Opilia campestris Engl. | Induces vomiting and bile release from the gall bladder | Mixed with soup | Not reported | [22] |

| Pyrenacantha malvifolia Engl. | Induces vomiting | Not reported | Pregnant women | [22] |

| Salvadora persica L. | Induces vomiting and bile release | Milk, salt | Not reported | [22] |

| Sericocomopsis hildebrandtii Schinz. | Stomachache, weight loss through induced vomiting, and bile release from the gall bladder | Milk | Pregnant women | [22] |

However, purgation and emesis are interpreted as signs that malaria is leaving the body and that the healing process has begun [22, 54]. It is reasonable that some side effects might also be masked through the use of more than one plant (or plant parts) especially for bitter remedies (such as Ajuga remota Benth.) [11, 38]. However, some herbalists are known to use more than one plant (plant parts) as a trick of keeping the secrecy of their formula [11]. Boiling of plant parts in goat fat, meat bone broth (as is done for Carissa edulis), taking decoctions mixed with milk (for Rhamnus prinoides), and mixing remedies with milk and salt for Salvadora persica L. [22] could serve as antidotes for potential side effects from use of the herbal preparations as reported elsewhere [33]. Some of the plants reported in this study such as Ajuga integrifolia and Croton macrostachyus were reported in Ethiopia to cause vomiting, nausea, headache, urination, and diarrhea when used for management of malaria [33]. Because the outcome of the treatment remains generally unclear due to lack of feedback from patients, herbalists rely on anecdotal reporting as far as efficacy and side effects are concerned.

Some antimalarial plants were reported as contraindicated to pregnant women and children (Table 2). Gathirwa et al. [50] reported that the posology of antimalarial herbal preparations in Kenya sometimes is dictated by the plant to be used, the traditional herbalist, the sex and the age of the patient, reiterating that pregnant women and children are often given lower dosages compared to other adults. This indicates the existence of research gaps with regard to the potential toxicities and corresponding counteracting mechanisms of antimalarial plants in Kenya. This gap represents a barrier to effective development and exploitation of indigenous antimalarial plants. In essence, some of the plants listed are reported to exhibit marked toxicity. Teclea simplicifoli (roots) is regarded to be poisonous by rural Kenyans [98]. Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don is another such plant known to house neurotoxic alkaloids [99]. Vincristine and vinblastine in this plant are highly cytotoxic antimitotics that block mitosis in metaphase after binding to mitotic microtubules [100]. Side effects such as kidney impairment, nausea, myelosuppression, constipation, paralytic ileus, ulcerations of the mouth, hepatocellular damage, abdominal cramps, pulmonary fibrosis, urinary retention, amenorrhoea, azoospermia, orthostatic hypotension, and hypertension [101–103] have been documented for antitumor drugs vincristine and vinblastine derived from this plant. These observations could partly explain why some antimalarial herbal preparations in Kenya are ingested in small amounts, applied topically, or are used for bathing. This gives a justification for the investigation of the plants for their potential toxicity.

3.5. Other Ethnomedicinal Uses of Antimalarial Plants Used in Rural Kenya

Most of the antimalarial plant species identified are used for traditional management of other ailments in Kenya and in other countries. Ajuga remota Benth (different parts), for example, are used to relieve toothache, severe stomachache, oedema associated with protein-calorie malnutrition disorders in infants when breast-feeding is terminated, pneumonia, and liver problems [52, 104, 105]. Such plants are used across different ethnic communities for managing malaria and can be a justification of their efficacy in malaria treatment [19].

3.6. Toxicity, Antiplasmodial, and Antimalarial Studies

Table 3 shows the list of some of the antimalarial plants used in Kenya with reports of toxicity/safety, antimalarial, and antiplasmodial activity evaluation. Across African countries, many antimalarial plants captured in this review have demonstrated promising therapeutic potential on preclinical and clinical investigations [68, 106–111]. Interestingly, antimalarial compounds have been identified and isolated from some of these species [62, 112].

Table 3.

Antiplasmodial/antimalarial activities of investigated plants used for malaria treatment in Kenya and their active chemical constituents.

| Plant | Part used | Extracting solvent | Antiplasmodial (IC50 μg/ml)/antimalarial activity (Plasmodium strain) | Active phytochemicals and toxicity information | Reference (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Justicia betonica L. | Shoot | Methanol, water, ether | 69.6 (K39), >100 (K39), 13.36 μg/ml | Justetonin (indole(3,2-b) quinoline alkaloid glycoside) | [117, 118] |

| Allium sativum L. | Synthetic | Ethanol | 50 mg/kg of ajoene suppressed development of parasitemia; ajoene (50 mg/kg) and chloroquine (4.5 mg/kg), given as a single dose, prevented development of parasitemia | Ajoene, nontoxic | [119] |

| Acmella caulirhiza | Whole plant | Dichloromethane | 9.939 (D6); 5.201 (W2) | No reports | [56] |

| Aloe kedongensis Reynolds | Leaves | Methanol | 87.7 (D6); 67.8 (W2) | Anthrone, C-glucoside homonataloin, anthraquinones, aloin, lectins | [120, 121] |

| Aloe secundiflora Eng. | Leaf exudate | Tested direct | 66.20 (K39) | No reports | [58] |

| Achyranthes aspera L. | Leaf, stem, roots, seeds | Ethanol | >100, 76.75, >100, >100 μg/ml | Alkaloids, glycosides, saponins, triterpenoids | [122] |

| Artemisia annua L. | Leaves | Water | 1.1 (D10), 0.9 (W2) | Sesquiterpenes and sesquiterpene lactones including artemisinin; safe and effective; artemisinin is safe for pregnant women | [120, 123, 124] |

| Bidens pilosa L. | Leaves | Dichloromethane, chloroform, water, and methanol | 8.5, 5, 11, 70 (D10) | No reports | [76] |

| Maytenus undata (Thunb.) Blakelock | Leaves | Dichloromethane, dichloromethane/chloroform (1 : 1), methanol, water | >100, 21, 60, >100 (D10) | No reports | [76] |

| Stem | Dichloromethane, dichloromethane/chloroform (1 : 1), methanol, water | 85, 24, 38, >100 (D10) | |||

| Roots | Dichloromethane, chloroform, methanol, water | 23, 36, 40, >100 (D10) | |||

| Rhus natalensis Bernh. ex Krauss | Stem bark, leaves | Ethanol | >50 (FcB1) | Triterpenoids | [50, 125] |

| Leaves, roots | Methanol | 43.92 (D6), 51.2 (W2); >100 (D6), 80.44 (W2) | |||

| Carissa edulis (Forssk.) Vahl | Stem bark, root bark, roots | Dichloromethane, chloroform, water, and methanol | 33 (D10), 6.41 (D6), >250, 148.53 and >250, >250 against ENT 30, and NF 54, respectively | Lignan, nortrachelogenin, cytotoxicity IC50 > 20, LD50 of 260.34, and 186.71 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | [48, 53, 76] |

| Euphorbia tirucalli L. | Leaves | Dichloromethane, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), methanol, water | 12, 23.5, >100, 83 (D10) | No reports | [76] |

| Psiadia punctulata | Twigs | Dichloromethane, water | 9, >100 (D10) | No reports | [76] |

| Leaves | Dichloromethane, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 14, 22.5, >100 (D10) | |||

| Whole plant | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 18 (D10), >100 (D10) | |||

| Ricinus communis L. | Leaves | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 27.5, >100 (D10) | No reports | [76] |

| Stems | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 8, >100 (D10) | |||

| Fruit | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 90, >100 (D10) | |||

| Catharanthus roseus G. Don | Leaves | Methanol | 4.6 (D6); 5.3 (W2) | Has neurotoxic alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, sesquiterpenes | [57, 126] |

| Caesalpinia volkensii Harms | Leaves | Decoction, ethanol, petroleum ether, methanol, water | 480, 481, 490, 858, 404 (FCA: 20 GHA), 923, 960, 250, 961, 563 (W2) | No reports | [11] |

| Artemisia afra Jacq. ex Willd | Leaves | Methanol | 9.1 (, D6); 3.9 (W2) | Acacetin, genkwanin, 7-methoxyacacetin; cytotoxicity observed in Vero cells | [57, 127] |

| Microglossa pyrifolia (Lam.) O. Ktze | Leaves | Chloroform, dichloromethane | <5 (both NF54 and FCR3) | E-Phytol, 6e-geranylgeraniol-19-oic acid; cytotoxic to human foetal lung fibroblast cell lines | [18, 25, 128, 129] |

| Cucumis aculeatus Cogn | Fruit | Water | >30 | No reports | [62] |

| Schkuhria pinnata (Lam.) | Whole plant | Water | 22.5 (D6); 51.8 (W2) | Schkuhrin I and schkuhrin II; methanol extract: low cytotoxicity against human cells; aqueous extracts: no toxicity observed in mice | [57, 130] |

| Solanecio mannii (Hook. f.) C. Jeffrey | Leaves | Methanol | 21.6 (3D7); 26.2 (W2) | Phytosterols, n-alkanes, and N-hexacosanol | [120, 128] |

| Tagetes minuta L. | Leaves | Ethyl acetate | 61.0% inhibition at 10 μg/ml | No reports | [130] |

| Tithonia diversifolia A. Gray | Leaves, aerial parts | Methanol, ether | 1.2 (3D7), 1.5 (W2), methanolic extract had 74% parasitemia suppression | Tagitinin C and sesquiterpene lactones; aerial parts are cytotoxic against cells from the human foetal lung fibroblast cell line. | [128, 131–133] |

| Vernonia amygdalina Del. | Leaves | Methanol/dichloromethane, ethanol | 2.7 (K1), 9.83. In vivo parasite suppression of between 57.2 and 72.7% in combination with chloroquine | Vernolepin, vernolin, vernolide, vernodalin and hydroxy vernodalin, and steroid glucosides; petroleum ether extract shows strong cytotoxicity | [111, 120, 130, 131, 134, 135] |

| Vernonia auriculifera (Welw.) Hiern | Leaves | Ethane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, water | >100, 37.7, 40.3, 55.2, >100 (K39) | No reports | [35] |

| Vernonia brachycalyx O. Hoffm. Schreber | Leaves | Chloroform/ethyl acetate, methanol | 6.6, 31.2 (K39) 29.6, 30.2 (V1/S) | 5-Methylcoumarin isomers, 16,17-dihydrobrachycalyxoloid | [58] |

| Vernonia lasiopus O. Hoffm. | Leaves | Methanol | 44.3 (D6); 52.4 (W2) | Sesquiterpene lactones, polysaccharides | [57, 120] |

| Markhamia lutea (Benth.) K. Schum. | Leaves | Ethyl acetate | 71% inhibition of P. falciparum at 10 μg/ml | Phenylpropanoid glycosides, cycloartane triterpenoids, musambins A-C, Candmusambiosides A-C | [130, 136] |

| Spathodea campanulata | Stem bark, leaves | Ethyl acetate, ethanol | 28.9% inhibition of P. falciparum | Quinone (lapachol) | [130, 137, 138] |

| Cassia didymobotrya Fres. | Leaves | Methanol | 23.4 (D6); undetectable (W2) | Alkaloids | [57] |

| Warbugia ugandensis Sprague | Stem bark | Methanol, water | 6.4 (D6); 6.9 (W2), 12.9 (D6); 15.6 (W2) | Coloratane sesquiterpenes, e.g., muzigadiolide | [57, 131, 139–141] |

| Dichloromethane | 69% parasite inhibition | ||||

| Carica papaya L. | Leaves | Ethyl acetate | 2.96 (D10), 3.98 (DD2) | Alkaloids, saponins, tannins, glycosides; no serious toxicity reported; carpaine, an active compound against P. falciparum had high selectivity and was nontoxic to normal red blood cells | [142, 143] |

| Maytenus senegalensis | Roots | Ethanol | 1.9 (D6), 2.4 (W2) | Terpenoids, pentacyclic triterpenes, e.g., pristimerin; no toxicity observed in ethanol extract | [144, 145] |

| Ethulia scheffleri S.Moore | Leaves | Chloroform/ethyl acetate/methanol | 49.8 (K39), 32.2 (V1/S) | No reports | [58] |

| Combretum molle G. Don | Stem bark | Acetone | 8.2 (3D7) | Phenolics, punicalagin | [146] |

| Momordica foetida Schumach | Shoot | Water | 6.16 (NF54); 0.35 (FCR3) | Saponins, alkaloid, and cardiac glycosides; no pronounced toxicity against human hepatocellular (HepG2) and human urinary bladder carcinoma (ECV-304, derivative of T-24) cells | [25, 134, 147] |

| Clutia abyssinica Jaub. & Spach | Leaves | Methanol | 7.8 (D6); 11.3 (W2) | Diterpenes | [57] |

| Croton macrostachyus Olive. | Leaves | Chloroform, dichloromethane | Chemotherapeutic effect of 66–82%, 2 (D6) | Triterpenoids including lupeol | [14, 56] |

| Flueggea virosa (Roxb. ex Willd) Voigt | Leaves | Water/methanol | 2.0 (W2) | Bergenin, nontoxic, extracts exposed to murine macrophages did not slow or inhibit growth of cells | [148, 149] |

| Erythrina abyssinica Lam. | Stem bark | Ethyl acetate | 83.6% inhibition of P. falciparum at 10 μg/ml | Chalcones (5-prenylbutein and homobutein), flavanones including 5-deoxyabyssinin II, abyssinin III, and abyssinone IV | [130, 137] |

| Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth | Bark, fruit | Chloroform/ethyl acetate, methanol | 59.9 (K39), 83.8 (V1/S); fruits had 165.9 (K39) | No reports | [58] |

| Trichilia emetica Vahl | Leaves, twigs | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1) | 3.5 for all (D10) | Kurubasch aldehyde | [76, 150] |

| Senna didymobotrya (Fresen.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby | Leaves, twigs | Methanol, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1) | >100 (K39), 9.5 (D10) | Quinones | [35, 76, 117] |

| Tamarindus indica L. | Stem bark | Water | 25.1% chemosuppressive activity at 10 mg/kg (P. berghei) | Saponins (leaves), tannins (fruits) | [73] |

| Harungana madagascariensis Lam. | Stem bark | Water, ethanol | 9.64 (K1); <0.5 with 28.6–44.8% parasite suppression | Quinones including bazouanthrone, ferutinin A, harunganin, harunganol A, anthraquinones, saponins, steroids | [137, 151–153] |

| Rotheca myricoides (Hochst.) Steane and Mabb | Leaves | Methanol | 9.51–10.56 and 82% parasite suppression at 600 mg/kg | No reports | [154] |

| Leucas calostachys Oliv. | Leaves | Methanol | 3.45 with parasite inhibition of 3.5–5.2% | No reports | [82] |

| Ajuga remota Benth. | Whole plant | Ethanol; decoction, ethanol, petroleum ether, methanol, and water | 55 (FCA/GHA), 57 (W2); 937, 55, 149, 504, 414 (FCA/GHA), 371, 57, 253, 493, 101 (W2) | Ajugarin-1, ergosterol-5,8-endoperoxide, 8-oacetylharpagide, steroids | [11, 14] |

| Suregada zanzibariensis Baill | Root bark | Water, methanol | ≤10 (K67), (ENT36) | Alkaloids | [96, 155] |

| Clerodendrum myricoides R. Br. | Root bark | Ethanol | 4.7 (D6); 8.3 (W2) | No reports | [156, 157] |

| Chloroform | >10 (D6) | Cytotoxicity, IC50 > 20.0 μg/ml | [48] | ||

| Hoslundia opposita Vahl. | Leaves | Ethyl acetate | 66.2% inhibition of P. falciparum at 10 μg/ml | Quinones, saponins, abietane diterpenes (3-obenzoylhosloppone) | [50, 130] |

| Roots; aerial parts | Methanol | 79.38 (D6), 64.21 (W2); 19.73 (D6), 29.41 (W2) | |||

| Leonotis nepetifolia | Leaves | Ethyl acetate, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 27.0% inhibition of P. falciparum at 10 μg/ml, 15, >100 (D10) | No reports | [76, 130] |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Leaves, whole plant | Ethanol | 68.14 (3D7); 67.27 (INDO) | No reports | [156, 157] |

| Ocimum gratissimum Wild | Leaves/twigs | Dichloromethane | 8.6 (W2) | Flavonoids | [56, 158] |

| Ocimum suave Wild | Leaves | Water (hot), chloroform/methanol mixture | 100 mg/kg/day of extracts provided 81.45% and 78.39% parasite chemosuppression | [71] | |

| Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | Leaves | Dichloromethane | No activity | No toxicity recorded | [56, 71] |

| Root bark | Water (hot), chloroform/methanol mixture | 100 mg/kg/day of extracts had 55.23% and 78.69% parasite chemosuppression | |||

| Azadirachta indica A. Juss. | Leaves | Water, methanol | 17.9 (D6); 43.7 (W2) | Terpenoids, isoprenoids, gedunin, limonoids: khayanthone, meldenin, and nimbinin; cytotoxicity LD50 of 101.26 and 61.43 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | [53, 144, 158–160] |

| Melia azedarach | Leaves | Methanol, dichloromethane | 55.1 (3D7), 19.1 (W2); 28 | No reports | [161, 162] |

| Ficus thonningii Blume | Leaves | Hexane | 10.4 | No reports | [163] |

| Cissampelos mucronata A. Rich. | Root bark, root | Methanol, ethyl acetate | 8.8 (D6); 9.2 (W2); root extract <3.91 (D6), 0.24 (W2) for the active compound (curine) | Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, curine | [74, 75, 157] |

| Acacia nilotica L. | Stem bark | Methanol | 100 mg/kg produced 77.7% parasitic inhibition | Tannins, flavonoids, terpenes | [53, 164] |

| Water, methanol | >250, 153.79 (ENT 30), 73.59, 70.33 (NF 54) | LD50 of 368.11 and 267.31 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | |||

| Albizia coriaria Welw. ex Oliv | Stem bark | Methanol | 15.2 (D6); 16.8 (W2) | Triterpenoids, lupeol, lupenone | [57] |

| Ageratum conyzoides L. | Whole plant | Dichloromethane, methanol | 2.15 (D6); 3.444 (W2), 11.5 (D6); 12.1 (W2) | Flavonoids | [57] |

| Albizia zygia (DC.) Macbr. | Stem bark | Methanol | 1.0 (K1) | Flavonoids mainly 3′,4′,7-trihydroxyflavone; aqueous extract is relatively safe on subacute exposure | [165, 166] |

| Maesa lanceolata Forsk. | Twig | Dichloromethane: methanol (1 : 1) | 5.9 (D10) | Lanciaquinones, 2,5, dihydroxy-3-(nonadec-14-enyl)-1,4-benzoquinone | [76, 128, 167] |

| Securidaca longipedunculata Fresen. | Leaves | Dichloromethane | 6.9 (D10) | Saponins, flavonoids, alkaloids, steroids | [168] |

| Prunus africana (Hook. f.) Kalkman | Stem bark | Methanol | 17.3 (D6); not detected (W2) | Terpenoids | [57] |

| Pentas longiflora Oliv. | Root | Methanol | 0.99 (D6); 0.93 (W2) | Pyranonaphthoquinones, pentalongin and psychorubrin, and naphthalene derivative mollugin; low cytotoxicity | [169] |

| Teclea nobilis Delile | Bark | 70% ethanol | 53.27% suppression of parasitemia at 700 mg/kg | Tannins, alkaloids, saponins, flavonoids | [167, 170] |

| Ethyl acetate | 54.7% inhibition of P. falciparum at 10 μg/ml | Quinoline alkaloids | [130] | ||

| Toddalia asiatica | Root bark, fruits, and leaves | Methanol, water, ethyl acetate, hexane | 6.8 (D6); 13.9 (W2); ethyl acetate fruit extract (1.80 mg/ml), root bark aqueous (2.43) (W2) | Furoquinolines (nitidine and 5,6-dihydronitidine), coumarins; acute and cytotoxicity of the extracts, with the exception of hexane extract from the roots showed LD50 > 1000 mg/kg and CC50 > 100 mg/ml, respectively | [84, 157] |

| Zanthoxylum chalybeum Engl. | Stem bark | Water | 4.3 (NF54); 25.1 (FCR3) | Chelerythine, nitidine, and methyl canadine; no toxicity recorded | [25, 71] |

| Trimeria grandifolia (Hochst.) Warb. | Leaves | Methanol | >50 (3D7) | No reports | [128] |

| Harrisonia abyssinica Olive. | Roots | Water, methanol | 4.4 (D6), 10.25 (W2); 89.74, 79.50 (ENT 30); 86.56, 72.66 (NF 54) | Limonoids and steroids; LD50 of 234.71 and 217.34 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | [53, 144] |

| Lantana camara L. | Leaves, leaves/twigs | Dichloromethane, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 8.7 (3D7), 5.7 (W2), 11 (D10), >100 (D10), >100 (D10) | Lantanine, sesquiterpenes, triterpenes, flavonoids | [76, 171] |

| Flacourtia indica (Burm. f.) Merr. | Roots | Dichloromethane, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 86.5 (D10), 78 (D10), >100 (D10) | No reports | [76] |

| Clausena anisata | Twigs, leaves | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 18 (D10), >100 (D10); 55, >100 (D10) | No reports | [76] |

| Flueggea virosa (Roxb.ex Willd.) Baill. | Leaves/twigs | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 19 (D10), 11.4 (D10) Alkaloids: Securinine and viroallosecurinine had IC50 of 2.7 and 2.9 |

Alkaloids, bergenin (root bark), securinine, and viroallosecurinine | [76, 172–174] |

| Lantana trifolia L. | Ariel parts | Petroleum ether, chloroform, ethanol | 13.2, >50, >50 (plasmodial lactate dehydrogenase) | Steroids, terpenoids, alkaloids, saponins | [125] |

| Bridelia micrantha (Hochst.) Baill. | Stem bark, leaves | Methanol | 158.7 (K1) | No reports | [175] |

| Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del. | Root bark | Chloroform | 3.49 (D6) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Sericocomopsis hildebrandtii | Root bark | Chloroform | 3.78 (D6) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Boscia angustifolia | Inner bark | Chloroform | >10.0 (D6); not active | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Acacia tortilis | Root bark | Chloroform | >10.0 (D6); not active | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Commiphora schimperi | Inner bark | Chloroform | 4.63 (D6) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Acacia mellifera | Inner bark | Chloroform | 4.48 (D6) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Fuerstia africana | Leaf, aerial parts, leaves | Chloroform, petroleum ether, methanol | 3.76 (D6), 1.5, <15 with >70% parasite suppression | Ferruginol, cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48, 65, 131, 176] |

| Psiadia punctulata | Root bark | Chloroform | >10.0 (D6); not active | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Ajuga integrifolia Buch.-Ham | Leaves | Methanol | 35.17% at 800 mg/kg/day parasite suppression | Alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, terpenoids, anthraquinone, steroids, tannins, phenols, and fatty acids; no lethal effect on mice in 24 h and within 10 days of observation | [177] |

| Albizia gummifera | Methanol | 0.16 (NF54), 0.99 (ENT 30) for alkaloidal fraction, spermine alkaloids had parasite suppression of 43–72% | Spermine alkaloids (budmunchiamine K, 6-hydroxybudmunchiamine K, 5-normethylbudmunchiamine K, 6-hydroxy-5-normethylbudmunchiamine K, 9-normethylbudmunchiamine K) | [178] | |

| Rhamnus staddo | Root bark | Chloroform | >10.0 (D6); not active | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Ocimum kilimandscharicum | Leaves, twigs | Dichloromethane | 0.843 (D6); 1.547 (W2) | No reports | [56] |

| Gutenbergia cordifolia | Leaves | Chloroform | 0.4 (D6) | Cytotoxicity IC50 = 0.2 μg/ml | [48] |

| Piper capense | Root bark | Chloroform | >10.0 (D6); not active | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Pentas lanceolata | Root bark | Chloroform | 5.15 (D6) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Clematis brachiata | Root bark | Chloroform | 4.15 (D6) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Ekebergia capensis | Inner bark, fruit, twigs | Chloroform, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1) | 3.97 (D6), 10, 18 (D10) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48, 76] |

| Rhamnus prinoides | Root bark | Chloroform | 3.53 (D6) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Olea europaea ssp. Africana | Inner bark, leaves, twigs | Chloroform, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1) | 9.48 (D6), 12, 13 (D10) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48, 76] |

| Pappea capensis | Inner bark | Chloroform | >10.0 (D6); not active | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Pittosporum viridiflorum Sims | Whole plant, leaves/flowers | Dichloromethane, methanol, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1) | 3, 10, 27.7, (D10), 28, 47, 70.5 (D10) | Triterpenoid estersaponin, pittoviridoside (saponins) | [76, 179, 180] |

| Podocarpus latifolius | Root bark | Chloroform | 6.43 (D6) | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Rumex abyssinicus Jacq. | Root | Dichloromethane | <15 | No reports | [176] |

| Rubus pinnatus Wild | Leaves | Ethanol | 20% parasite suppression | No reports | [130] |

| Zanthoxylum gilletii | Stem bark | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1) | 2.52 (W2), 1.48 (D6), 1.43 (3D7) | Nitidine, seas amine 8-acetyl dihydrochelerythrine | [86, 176] |

| Solanum incanum L. | Leaves | Chloroform/methanol | 31% parasite suppression | No reports | [87] |

| Rhoicissus tridentata | Roots | Water | >40.0 | No reports | [62] |

| Acacia hockii | Root bark | Chloroform | >10.0 (D6); not active | Cytotoxicity IC50 > 20 μg/ml | [48] |

| Lippia javanica (Burm.f.) Spreng | Roots | Chloroform/ethyl acetate, methanol | 16.7, 40.6 (K39), 19.2, 40.1 (V1/S) | No reports | [58, 76] |

| Roots, stem | Dichloromethane, methanol, dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1) | 3.8, 27, 24 (D10), 4.5, 21.8, 29.8 (D10) | |||

| Premna chrysoclada (Bojer) Gürke | Roots, leaves | Methanol | 27.63 (D6), 52.35 (W2); 7.75 (D6), 9.02 (W2) | Not cytotoxic at 100 μg/ml | [50] |

| Allophylus pervillei Blume | Roots, stem bark | Methanol | 45.62 (D6), 48.91 (W2); >100 (D6),>100 (W2) | Not cytotoxic at 100 μg/ml | [50] |

| Aganthesanthemum bojeri Klotzsch. | Whole plant | Methanol | 55.3 (D6), 55.97 (W2) | Not cytotoxic at 100 μg/ml | [50] |

| Abrus precatorius L. | Leaves | Methanol | 85.59 (D6), >100 (W2) | Not cytotoxic at 100 μg/ml | [50] |

| Combretum illairii Engl. | Stem bark, leaves | Methanol | 55.96 (D6), 58.54 (W2); 24.21 (D6), 33.31 (W2) | Not cytotoxic at 100 μg/ml | [50] |

| Grewia plagiophylla K. Schum | Leaves, stem bark | Methanol | 13.28 (D6), 34.2 (W2); >100 (D6), >100 (W2) | Not cytotoxic at 100 μg/ml | [50] |

| Combretum padoides Engl. & Diels | Roots | Methanol | 21.73 (D6), 59.43 (W2) | Not cytotoxic at 100 μg/ml | [50] |

| Uvaria acuminata | Leaves, roots | Methanol | 51.13 (D6), >100 (W2); 8.89 (D6), 6.90 (W2) | Cytotoxic with CC50 of 2.37 μg/ml. | [50] |

| Ormocarpum trachycarpum | Roots | Chloroform/ethyl acetate, methanol, water | 19.6, 41.7, 79.4 (K39); 17.5, 32.8 (V1/S) | No reports | [58] |

| Plectranthus sylvestris Gurke | Leaves | Chloroform/ethyl acetate, methanol | 41.1, 56.2 (K39); 61.0 (V1/S) | No reports | [58] |

| Turraea robusta | Root bark | Water, methanol | 25.32, 2.09 (D6), 42.41, 10.32 (W2) | IC50 of 24.38 and 45.72 μg/ml for methanol and aqueous extracts against Vero cells (cytotoxic) | [49] |

| Lannea schweinfurthii | Stem bark | Water, methanol | 10.55 and 75.90, 11.38 and 36.26 (D6 and W2) | IC50 of 225.25 and 3256.52 μg/ml for methanol and aqueous extracts against Vero cells | [49] |

| Sclerocarya birrea | Stem bark | Water, methanol | 18.96 and 71.74, 5.91 and 24.96 (D6 and W2) | IC50 of 361.24 and 3375.22 μg/ml for methanol and aqueous extracts against Vero cells | [49] |

| Withania somnifera | Stem bark | Water, methanol | >250, >250 (ENT 30); 145.86, 125.59 (NF 54) | LD50 of 301.44 and 207.27 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | [53] |

| Zanthoxylum usambarense | Stem bark | Water, methanol | 14.33, 5.25 (ENT 30); 5.54, 3.20 (NF 54) | LD50 of 260.90 and 97.66 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | [53] |

| Fagaropsis angolensis | Stem bark | Water, methanol | 10.65, 6.13 (ENT 30); 5.04, 4.68 (NF 54) | LD50 of 173.48 and 57.09 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | [53] |

| Myrica salicifolia | Stem bark | Water, methanol | 85.97, 66.84 (ENT 30); 55.89, 51.07 (NF 54) | LD50 of 328.22 and 320.17 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | [53] |

| Strychnos henningsii Gilg | Stem bark | Water, methanol | 73.39, 67.16 (ENT 30); 190.0, 159.71 (NF 54) | LD50 of 293.93 and 101.22 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | [53] |

| Neoboutonia macrocalyx | Stem bark | Water, methanol | 92.85, 84.56 (ENT 30); 78.44, 78.40 (NF 54) | LD50 of 41.69 and 21.04 μg/ml for water and methanol extracts | [53] |

| Urtica massaica Mildbr. | Aerial parts | Hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, water, methanol | >100 (K39) | No reports | [35] |

| Uvaria scheffleri Diels | Leaves, stem, root bark | Petroleum ether, dichloromethane, methanol | 5–500 (K1) | Indole alkaloid-(±L)-schefflone, uvaretin, diuvaretin | [181, 182] |

| Rauwolfia cothen | Root bark | Petroleum ether, dichloromethane, methanol | 0–499 (K1) | Yohimbine, an indole alkaloid | [183, 184] |

| Tridax procumbens L. | Whole plant | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1), water | 17 (D10), >100 (D10) | Bergenin | [76, 184, 185] |

| Centella asiatica | Leaves | Dichloromethane/methanol (1 : 1) | 8.3 (D10) | Alkaloids, sesquiterpenes | [76, 186] |

| Ficus sur | Stem bark | Hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, water, methanol | 19.2, 9.0, >100, >100, >100 (K39) | No reports | [35] |