Abstract

Background and purpose:

Cancer prevalence has increased in the last century posing psychological, social, and economic consequences. Chemotherapy uses chemical molecules to control cancer. New studies have shown that dihydropyrimidinethione (DHPMT) derivatives have the potential of being developed into anticancer agents.

Experimental approach:

New derivatives of DHPMTs and a few acyclic bioisosters were synthesized via Biginelli reaction and assessed for their toxicity against gastric (AGS) and breast cancer (MCF-7) cell lines through MTT method.

Findings / Results:

Chemical structures of all synthesized N-heteroaryl enamino amides and DHPMTs were confirmed by spectroscopic methods. Result of biological assessment exhibited that none of the tested agents was more cytotoxic than cis-platin against AGS and MCF-7 cell lines and compound 2b was the most cytotoxic agent against AGS (IC50 41.10 μM) and MCF-7 (IC50 75.69 μM). Cytotoxic data were mostly correlated with the number of H-bond donors within gastric and breast cancer cells.

Conclusion and implications:

It was realized that DHPMTs were able to inhibit the growth of cancer cells much better than acyclic enamino amides and moreover; N-(4-methylbenzothiazol-2-yl) DHPMT derivative (2b) supposed possible interaction with a poor electron site of target due to the lipophilic nature of benzothiazole ring and also less electron rich nature than isoxazole. Similar scenario was observed with acyclic enamino amides in which incorporation of sulfur and nitrogen containing heterocycles doubled the cytotoxic effects. Results of the present contribution might assist in extending the scope of DHPMTs as privileged medicinal scaffolds.

Keywords: Cancer, Cytotoxicity, Dihydropyrimidinethione, Enamino amide, MTT

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the largest family of non- infectious diseases. There is a common point in all types of this disease, which is the high and non-controllable multiplication of certain cells in the patient’s body.

The causes of cancer are very diverse and widespread. It has been revealed that 90-95% of cancers are the result of genetic mutations caused by environmental or lifestyle factors and the remaining 5 to 10 percent are due to heredity (1).

Environmental factors include lifestyle, economics, behavior, and the living environment.

In a smaller perspective, these factors include chemicals and outside factors (25-30%), obesity (30-35%), infections (15-20%), and radiation (15-20%) (2).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) on September 12, 2018, there were 18.1 million new cases of cancer and 9.6 million deaths due to cancer worldwide this year. Starting from September 12, 2013 to September 12, 2018, there were 43.8 million deaths recorded due to cancer worldwide. These statistics indicate the high importance of cancer in death rates (3). In the light of the high prevalence of the disease, its treatment or control is a key priority (4).

Heterocycles are privileged structures in biochemical processes since their chemical structure is present in important biological compounds and living cells. Among the heterocyclic compounds existing in nature, nitrogen-containing ones are more important than others due to their distribution in nucleic acids, amino acids, and also their interference in the physiological processes of plants and animals. Recent studies have shown that N- heteroaryl derivatives can be effective in control of cancer (5,6). Enamino amide scaffolds were demonstrated to kill cancer cells, which have significant cytotoxic effects on prostate PC-3, colon HT-29, and breast MDA- MB-231 cell lines (7).

Dihydropyrimidine derivatives (DHPMs) are present in many compounds such as organic bases, coenzymes, vitamins, and uric acid. Therefore, they possess many properties. Studies have shown that the derivatives of these compounds exhibit antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, anticancer, antimalaria, and antihypertensive effects (8,9,10,11,12,13). Many anticancer antimetabolites such as 5- fluorouracil, camphor, cytarabine, and gemcitabine bear a pyrimidine core and they are still used in some countries as a common treatment protocols (14). Moreover, several studies indicated DHPM compounds with heterocyclic rings inhibit the growth of cancer cell lines (15,16).

With the aim of achieving more diverse structural patterns with the potential for selective cytotoxic effects on cancer cells, this project was contributed to the synthesis and structural determination of a number of N- heteroaryl enamino amides and dihydropyrimidinethiones (DHPMTs) with different heteroaryl substituents via a cost- effective method and their subsequent cytotoxicity assessment against AGS and MCF- 7 cancer cells by MTT calorimetric assay (17).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemistry

All materials and reagents were purchased from Merck (Germany) and Aldrich (India) Companies and used without further purification. Melting points (MP) were determined using an Electro thermal type 9200 MP apparatus (England) and uncorrected. Infra-Red (IR) spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer-400 FT-IR spectrophotometer (England) while proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker DRX400 spectrometer (400 MHz) were recorded on an Agilent 7890A spectrometer.

Typical procedure for the synthesis of N- heteroaryl enamino amide derivatives

For synthesis of enamino amide derivatives, first the β-ketoamide intermediates were synthesized by dissolving 4 mmol of corresponding aromatic amine in a minimum amount of xylene. After obtaining a clear solution, 5 mmol of 2,2,6-trimethyl-1,3-dioxin- 4-one was added and the solution was refluxed (4 to 24 h). The precipitate was filtered and washed twice with petroleum ether (2 × 3 mL). Obtained products were further purified via recrystallization with cold ethanol and dried in desiccator for one day. Structures of obtained β- ketoamide intermediates were confirmed by thin layer chromatography (TLC) and MPs (18).

In the second phase of the synthesis, the enamino amides were prepared from β- ketoamide intermediates via adding 4 mmol of P-ketoamide to 4 mmol of 4-methylbenzyl amine in ethanol or isopropyl alcohol and refluxing for 24 h till formation of the precipitate. The precipitate was filtered and washed twice with appropriate solvent (2 × 3 mL). Obtained products were dried in desiccator for one day. Structural identification of the synthesized derivatives was performed through MP, TLC, 1H-NMR, mass spectrometry (MS), and infrared (IR).

Typical procedure for the synthesis of DHPMTs

In order to synthesize the DHPMT derivatives, to a solution of 1.2 mmol P-ketoamide, 1.3 mmol thiourea, 0.4-0.5 mmol CoSO4 in 5 mL ethanol, and 1 mmol benzaldehyde were added. The resulting mixture was refluxed for 24 h. Following reflux, the heater was switched off and after achieving room temperature, some water and ice (deionized water) were added to the flask in order to remove the remaining reactants. After this step, the contents of the flasks were washed with plenty of cold water and the reaction progress was analyzed by TLC and MP (19).

Biological assessment

Reagents and chemicals

RPMI 1640, fetal bovine serum (FBS), trypsin, and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from Biosera (Ringmer, UK). 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)- 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was obtained from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO, USA) and penicillin/streptomycin was purchased from Invitrogen (San Diego, CA, USA). Cisplatin and dimethyl sulphoxide were obtained from EBEWE Pharma (Unterach, Austria) and Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), respectively.

Cell lines

MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) and AGS (human gastric cancer) cells were obtained from the National Cell Bank of Iran, Pasteur Institute, Tehran, I.R. Iran. All cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, and 100 units/mL penicillin-G and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were grown in monolayer cultures.

Cytotoxic effect

Cell viability following exposure to the synthetic compounds was estimated using MTT reduction assay. Cells were plated in 96-well microplates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well (200 μL per well). Control wells contained no drugs and blank wells contained only growth medium for background correction. After cell attachment, the medium was removed, and cells were incubated with a serum-free medium containing 1 mg/mL of the synthetic compounds by 1/4 serial dilutions. Compounds were all first dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then diluted in medium, therefore the maximum concentration of DMSO in the wells did not exceed 0.5%. Cells were further incubated for 24 h. At the end of the incubation time, the medium was removed and MTT solution was added to each well at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL and plates were incubated for another 4 h at 37 °C. Then formazan crystals were solubilized in 200 μL DMSO. The optical density was measured at 570 nm with background correction at 655 nm using a Bio-Rad microplate reader (Model 680, USA). The percentage of inhibition of viability compared to control wells was calculated for each concentration of the compound and IC50 values were calculated with SigmaPlot version 12.5. The absorbance of wells containing no cells was subtracted from sample well absorbance before calculating the percentage of inhibition. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate.

RESULTS

Chemistry

Chemical structures of all synthesized N-heteroaryl enamino amides and DHPMTs were confirmed by spectroscopic methods.

3- (( 4- Methylbenzyl) amino) - N - (5- methyl- isoxazol-3-yl)but-2-enamide (1a)

White crystal, MP: 173-175 °C; IR (KBr) Vmax (cm-1): 3236, 3146, 3052, 1653, 1618, 1597; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 10.01 (1H, brs, NH-amide), 9.41 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, NH-enamine), 7.17 (4H, brs, CH-phenyl), 6.60 (1H, s, C4´H-isoxazole), 4.65 (1H, s, CH- alkene), 4.38 (2H, d, J = 6 Hz, CH2-benzyl), 2.30 (3H, s, 5´-CH3-isoxazole), 2.28 (3H, s, Ph- CH3), 1.88 (3H, s, CH3); MS m/z (%): 285 (13) [M+], 242 (7), 159 (25), 105 (100), 77 (19).

3- ((4 -Methylbenzyl)amino) -N- (thiazole-2-yl) but-2-enamide (2a)

Yellow crystal, MP: 191-193 °C; IR (KBr) Vmax (cm-1): 3204, 3007, 2917, 1643, 1582, 1540; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 11.27 (1H,brs, NH-amide), 9.34 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, NH- enamine), 7.35 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, C4’H-thiazole), 7.17 (4H, brs, CH-phenyl), 7.00 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, C5´H-thiazole), 4.73 (1H, s, CH-alkene), 4.24 (2H, d, J = 6 Hz, CH2-benzyl), 2.28 (3H, s, Ph- CH3), 1.90 (3H, s, CH3).

N-(6-Methoxybenzo [d] thiazole-2-yl)-3-((4- methylbenzyl)amino)but-2-enamide (3a)

White crystal, MP: 173-175 °C; IR (KBr) Vmax (cm-1): 3209, 3018, 2921, 1650, 1593, 1549, 1270; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 11.39 (1H, brs, NH-amide), 9.40 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, NH-enamine), 7.51 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, C4’H-benzothiazole), 7.44 (1H, s, C7´H- benzothiazole), 7.19 (4H, brs, CH-phenyl), 6.95 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, C5´H-benzothiazole), 4.75 (1H, s, CH-alkene), 4.44 (2H, d, J = 6 Hz, CH2- benzyl), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 2.29 (3H, s, Ph- CH3), 1.93 (3H, s, CH3); MS m/z (%): 367 (8) [M+], 246 (100), 218 (43), 189 (14), 77(17).

N-(4-Methylbenzo [d] thiazole-2-yl)-3-((4- methylbenzyl)amino)but-2-enamide (4a)

Yellow crystal, MP: 195-197 °C; IR (KBr) Vmax (cm-1): 3136, 3023, 2921, 1645, 1589, 1536; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 11.63 (1H,brs, NH-amide), 9.43 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, NH-enamine), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, C7´H-benzothiazole), 7.19 (4H, brs, CH- Phenyl), 7.17 (1H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, C5´H- benzothiazole), 6.95 (1H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, C6’H- benzothiazole), 4.79 (1H, s, CH-alkene), 4.45 (2H, d, J = 6 Hz, CH2-benzyl), 2.52 (3H, s, 4´- CH3-benzothiazole), 2.29 (3H, s, Ph-CH0, 194 (3H, s, CH3); MS m/z (%): 351 (13) [M+], 231 (21), 163 (39), 105 (100), 91 (22), 77(9).

N-(6-Methylbenzo [d] thiazole-2-yl)-3-((4- methylbenzyl)amino)but-2-enamide (5a)

White crystal, MP: 230-232 °C; IR (KBr) Vmax (cm-1): 3199, 3041, 2923, 1644, 1595, 1532; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 11.44 (1H, brs, NH-amide), 9.42 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, NH-enamine), 7.63 (1H, s, C7´H- benzothiazole), 7.49 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, C4’H- benzothiazole), 7.19 (4H, brs, CH-phenyl), 7.16 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, C5´H-benzothiazole), 4.76 (1H, s, CH-alkene), 4.45 (2H, d, J = 6 Hz, CH2- benzyl), 2.37 (3H, s, 6´-CH3-benzothiazole), 2.29 (3H, s, Ph-CH0, 194 (3H, s, CH3); MS m/z (%): 351 (11) [M+], 231 (19), 146 (9), 105 (100), 77(8).

N- (4-(4 -Bromophenyl) thiazole-2-yl)-3- ((4- methylbenzyl)amino)but-2-enamide (6a)

White crystal, MP: 128-130 °C; IR (KBr) Vmax (cm-1): 3349, 3247, 3095, 3015, 2916, 1637, 1592, 1531; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO- d6) δ (ppm) 11.54 (1H, brs, NH-amide), 9.36 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, NH-enamine), 7.81 (2H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, CH-phenyl), 7.59 (2H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, CH-phenyl), 7.51 (1H, s, C5´H-thiazole), 7.18 (4H, brs, CH-Phenyl), 4.75 (1H, s, CH-alkene), 4.43 (2H, d, J = 6 Hz, CH2-benzyl), 2.28 (3H, s, Ph-CH3), 1.92 (3H, s, CH3); MS m/z (%): 443 (15) [M+], 349 (15), 334 (68), 105 (100), 81(10).

3- ((4- Methylbenzyl) amino)-N-phenylbut -2- enamide (7a)

White crystal, MP: 135-137 °C; IR (KBr) Vmax (cm-1): 3290, 3134, 3018, 2918, 1622, 1592, 1523; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 9.39 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, NH-enamine), 9.18 (1H, brs, NH-amide), 7.54 (2H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, CH-Phenyl), 7.18-7.22 (6H, m, CH-Phenyl), 6.89 (1H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, CH-Phenyl), 4.60 (1H, s, CH-alkene), 4.37 (2H, d, J = 6 Hz, Cm- benzyl), 2.29 (3H, s, Ph-CH3), 1.89 (3H, s, CH3); MS m/z (%): 281 (13) [M+], 146 (6), 105 (100), 251 (46), 77(9).

6- Methyl -N,4- diphenyl-2- thioxo-1,,2,3,4- tetrahydropyrimidine-5-carboxamide (1b)

White crystal, MP: 165-167 °C; IR (KBr) Vmax (cm-1): 3486, 3284, 3181, 3060, 3012, 1679, 1630, 1589; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm)10.11 (1H, brs, NH-amide), 9.84 (1H, brs, N1H), 9.55 (1H, brs, N3H), 7.64 (2H, d, J = 8 Hz, CH-phenyl), 7.33-7.46 (8H, m, CH-phenyl), 5.49 (1H, brs, C4H-DHPM), 2.16 (3H, s, CH3-DHP);MS m/z (%): 323 (74) [M+], 231 (100), 203 (15), 77(28).

6-Methyl-4-phenyl-N-(4-methylbenzothiazol-2- yl)-2-thioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-5- carboxamide (2b)

White crystal, MP: 251-253 °C; IR (KBr) Vmax (cm-1): 3413, 3267, 3154, 1678, 1629, 1584; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 12.07 (1H, brs, NH-amide), 10.28 (1H, brs, N1H), 9.70 (1H, brs, N3H), 7.55 (1H, d, J = 3.2 Hz, C4’H-thiazole), 7.45 (3H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, CH- phenyl),7.35 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, CH-phenyl), 7.25 (1H, brs, C5´H-thiazole), 5.66 (1H, brs, C4H-DHPM), 2.25 (3H, s, CH3-DHP); MS m/z (%): 330 (64) [M+], 253 (25), 231 (56), 209 (100), 172 (51), 77(29).

The MPs, molecular weight, and calculated lipophilicity (ClogP) of all synthesized compound are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Synthesized derivatives of N-heteroaryl enamino amide and dihydropyrimidinethiones.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | R | Melting points (°C) | Molecular weight | calculated lipophilicity | Yield (%) |

| 1a | 5-Methyl isoxazol-3-yl | 173-175 | 285.35 | 3.148 | 70 |

| 2a | 2-Thiazolyl | 191-193 | 287.38 | 3.331 | 62 |

| 3a | 6-Methoxy benzothiazol-2-yl | 173-175 | 367.14 | 5.227 | 57 |

| 4a | 4-Methyl benzothiazol-2-yl | 195-197 | 351.47 | 5.424 | 78 |

| 5a | 6-Methyl benzothiazol-2-yl | 230-232 | 351.47 | 5.424 | 36 |

| 6a | 4-(4-Bromophenyl) thiazol-2-yl | 128-130 | 442.38 | 6.300 | 34 |

| 7a | Phenyl | 135-137 | 280.37 | 4.095 | 84 |

| 1b | Phenyl | 165-167 | 323.41 | 3.037 | 17 |

| 2b | 4-Methylbenzothiazol-2-yl | 251-253 | 330.42 | 2.274 | 69 |

Biological assessment

Prepared N-heteroaryl enamino amides and DHPMTs were assessed for their cytotoxic activity against two human cancer cell lines (AGS and MCF-7) in terms of IC50 values (Table 2). As could be seen from the obtained results, none of the tested agents was more cytotoxic than cis-platin for AGS and MCF-7 cell lines. Compound 2b bearing 4- methylbenzothiazol-2-yl moiety at C6 of DHPMT ring was the most cytotoxic agent within both cell lines.

Table 2.

Cytotoxic activity of N-heteroaryl enamino amides and dihydropyrimidinethiones assessed by the MTT reduction assay. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | R | IC50 (μM) | |

| AGS cells | MCF-7 cells | ||

| 1a | 5-Methyl isoxazol-3-yl | 2196.40 ± 36.32 | 2367.91 ± 41.26 |

| 2a | 2-Thiazolyl | 453.14 ± 14.29 | 761.90 ± 20.14 |

| 3a | 6-Methoxy benzothiazole-2-yl | 1946.01 ± 49.52 | 2375.28 ± 33.21 |

| 4a | 4-Methyl benzothiazole-2-yl | 1291.58 ± 28.39 | 1429.92 ± 46.99 |

| 5a | 6-Methyl benzothiazole-2-yl | 1468.21 ± 19.32 | 1659.40 ± 17.26 |

| 6a | 4-(4-Bromophenyl) thiazole-2-yl | 617.62 ± 22.62 | 487.20 ± 28.43 |

| 7a | Phenyl | 2223.92 ± 64.16 | 2451.45 ± 39.82 |

| 1b | Phenyl | 98.48 ± 10.62 | 149.13 ± 9.01 |

| 2b | 4-methylbenzothiazol-2-yl | 41.10 ± 5.01 | 75.69 ± 7.87 |

| Cis-platin | - | 11.49 ± 0.90 | 6.02 ± 2.29 |

Correlation of cytotoxic effects with physicochemical parameter

In order to explore the possible correlation of cytotoxic effects to a few physicochemical parameters, linear regression analysis was done for the data driven from AGS and MCF-7 cell lines. As shown in Fig. 1A-F) cytotoxic data were mostly correlated with the number of H- bond donors within gastric (Fig. 1D) and breast (Fig. 1I) cancer cells. Such trend might emphasize on the determinant role of polar hydrogens within the cytotoxic agents in AGS and MCF-7 cell lines and also possible presence of H-bond acceptors within the site of actions in cancer cell lines.

Fig. 1.

Linear Correlation of physicochemical data vs cytotoxic effects against AGS and MCF-7 cells for dihydropyrimidinethiones; (A) MW vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 = 0.05); (B) ClogP vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 = 0.09); (C) No. HBA vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 = 0.23); (D) No. HBD vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 = 0.49); (E) No. RTBs vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 = 0.36); (F) MW vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 = 0.08); (G) ClogP vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 = 0.07); (H) No. HBA vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 = 0.26); (I) No. HBD vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 =0.48); (J) No. RTBs vs IC50 (μM) against AGS cells (R2 = 0.35). MW; Molecular weight; ClogP, calculated lipophilicity; HBA, hydrogen bond acceptors; HBD, hydrogen bond donors; . RTBs; number of rotatable bonds.

DISCUSSION

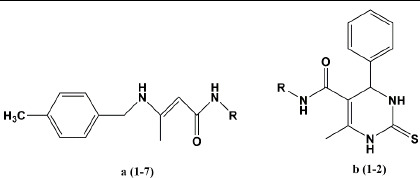

Synthetic routes to compounds (1-7) a and (1-2) b are depicted in Schemes 1 and 2. The mechanism of synthesis first involves nucleophilic attack of thiourea nitrogen to the aldehyde carbonyl group followed by tautomerism, intramolecular nucleophilic attack and water removal to give the imine intermediate. Carbonyl group of 3-oxo butane amide captures proton to produce enol which reacts with imine intermediate to give the second intermediate that will be converted to final DHPMT derivative via cyclization and water removal.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route toward en-amino amide derivatives (1a-7a).

Scheme 2.

Synthetic route toward dihydropyrimidinethiones (1b-2b).

The effect of the acyclic enamino amides were found to be about 50 times weaker than DHPMTs. Among the enamino amides, compound 2a bearing N-(2-thiazolyl) substituent was the superior agent (AGS; IC50 453.14 μM and MCF-7; IC50 761.90 μM). A closer observation of data revealed that addition of a 4-bromophenyl moiety to C4 of thiazole ring (6a) led to i ncrease cytotoxicity on MCF-7 cell line (IC50 487.20 μM).

The relative toxicity of DHPMTs, as mentioned above, is much higher than the enamino amide derivatives. The benzothiazole ring is also found in compound 2b that exhibited the best performance in this project. Thiazole is an electron-rich ring than oxazole suggesting a possible interaction with the poor electron site of the target. Similar results were achieved before (20). Electron deficiency is in the order of isoxazole > thiazole > benzene. Compound 7a (R = benzene) is less active than 2a (thiazole) whereas benzene is more electron rich. Perhaps, lipophilicity of thiazole helps it to show better effect than oxazole (2a > 1a > 7a). Other studies also suggested a crucial role of thiazole ring in enhancement of cytotoxic effects within colon, liver, breast, and gastric cancer cells (21,22).

Significant decrease of cytotoxic effect in compound 1a with N-(5-methyl isoxazol-3-yl) substituent indicated an important influence of heterocyclic ring on biological activity. Isoxazole ring is composed of oxygen but not sulfur and hence electron donation effect would be attenuated in comparison with thiazole.

Lower activity of 3a, 4a, and 5a might be probably related to their bulky structure and steric hindrance within the site of action. One exception to this could be seen for compound 6a which includes 4-(4-bromophenyl) thiazole- 2-yl) substituent. Possible rationalization would be the flexibility of 6a around its thiazole ring (in contrast to 3a, 4a, and 5a) which provided desirable accommodation of the compound in the site of action. Similar results could be detected for dihydropyridine compounds in a way that rigid bulky substituents led to attenuated cytotoxic activity against MCF-7 cell lines (17).Moreover; relatively good cytotoxic effects could be seen for rotatable bulky substituents on DHPM ring (23).

Comparing the cytotoxicity of 4a and 5a indicated the effect of isomerism (4-methyl benzothiazole and 6-methyl benzothiazole) on biological activity. It was interestingly observed that 4-methyl derivative had better cytotoxic effect than 6-methyl analogue within both cell lines. A general trend in the cytotoxicity of compounds was that almost all the derivatives were better cytotoxic agents against gastric cell lines.

CONCLUSION

Cytotoxicity tests showed that the acyclic enamino amide compounds did not have sufficient potency to inhibit AGS and MCF-7 cancer cells, while DHPMTs performed much better than the enamino amides. Results of the study indicated that the toxicity of acyclic enamino amides were weaker than DHPMTs. Additionally, incorporation of non-bulky electron-deficient rings such as thiazole into the nitrogen atom of 5-carboxamide moiety of enamino amide and DHPMTs increases the cytotoxicity against gastric (AGS) and breast (MCF-7) cancer cells (2a>1a>7a), but if the attached rings contain sterically hindered bulky substituents or more electron withdrawing groups such as benzothiazole or isoxazole, the effect would be decreased. This study indicated that DHPMTs and their optimized derivatives could be considered as privileged medicinal scaffolds for inhibiting the growth of gastric and breast cancer cells.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATMENT

Authors declare that no conflict of interest for this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors contributed equally in this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially (Grant No. IR.ARUMS.REC.1397.007) supported by Vice Chacellery of Research of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, I.R. Iran.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. DOI: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand P, Kunnumakara AB, Sundaram C, Harikumar KB, Tharakan ST, Lai OS, et al. Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes. Pharm Res. 2008;25(9):2097–2116. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9661-9. DOI: 10.1007/s11095-008-9661-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farhood B, Geraily G, Alizadeh A. Incidence and mortality of various cancers in Iran and compare to other countries: a review article. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47(3):309–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam LK LKT Laboratories Inc; assignee. Heterocyclic compounds for cancer chemoprevention United States Patent, 2000 No US 6166003A. https://europepmcorg/article/pat/us6166003 . inventor.

- 6.Penthala NR, Madhukuri L, Thakkar S, Madadi NR, Lamture G, Eoff RL, et al. Synthesis and anti-cancer screening of novel heterocyclic-(2^)-1,2,3-triazoles as potential anti-cancer agents. Medchemcomm. 2015;6(8):1535–1543. doi: 10.1039/C5MD00219B. DOI: 10.1039/C5MD00219B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathew B, Hobrath JV, Lu W, Li Y, Reynolds RC. Synthesis and preliminary assessment of the anticancer and Wnt/p-catenin inhibitory activity of small amide libraries of fenamates and profens. Med Chem Res. 2017;26(11):3038–3045. doi: 10.1007/s00044-017-2001-z. DOI: 10.1007/s00044-017-2001-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Sayed WA, Nassar IF, Adel AH. C-Furyl glycosides, II: synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of C-furyl glycosides bearing pyrazolines, isoxazolines, and 5,6-dihydropyrimidine-2(1#)- thiones. Monatsh Chem. 2009;140(4):365–370. DOI: 10.1007/s00706-008-0033-2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giffin MJ, Heaslet H, Brik A, Lin YC, Cauvi G, Wong CH, et al. A copper (I)-catalyzed 1,2,3-triazole azide-alkyne click compound is a potent inhibitor of a multidrug-resistant HIV-1 protease variant. J Med Chem. 2008;51(20):6263–6270. doi: 10.1021/jm800149m. DOI: 10.1021/jm800149m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou Y, Zhao Q, Liao J, Hu H, Yu S, Chai X, et al. New triazole derivatives as antifungal agents: synthesis via click reaction, in vitro evaluation and molecular docking studies. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22(8):2959–2962. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.042. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirisha K, Achaiah G, Reddy VM. Facile synthesis and antibacterial, antitubercular, and anticancer activities of novel 1,4-dihydropyridines. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2010;343(6):342–352. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200900243. DOI: 10.1002/ardp.200900243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayanaswamy VK, Gleiser RM, Chalannavar RK, Odhav B. Antimosquito properties of 2-substituted phenyl/benzylamino -6 -(4-chlorophenyl) -5 - methoxycarbonyl-4-methyl-3,6-dihydropyrimidin-1 - ium chlorides against Anopheles arabiensis. Med Chem. 2014;10(2):211–219. doi: 10.2174/157340641002140131164945. DOI: 10.2174/157340641002140131164945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Hamouly WS, Amine KM, Tawfik HA, Dawood DH. Synthesis and antihypertensive activity of certain substituted dihydropyridines and pyrimidinones. Egypt Pharm J. 2013;12(1):20–27. DOI: 10.7123/01.EPJ.0000426587.41764.d4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palucki M. Pyrimidines. In: Li JJ, Gribble GW, editors. Tetrahedron Organic Chemistry Series. Vol. 26. United Kingdom: Elsevier Ltd; 2007. pp. 475–509. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prashantha Kumar BR, Sankar G, Nasir Baig RB, Chandrashekaran S. Novel Biginelli dihydropyrimidines with potential anticancer activity: a parallel synthesis and CoMSIA study. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44(10):4192–4198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.05.014. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soumyanarayanan U, Bhat VG, Kar SS, Mathew JA. Monastrol mimic Biginelli dihydropyrimidinone derivatives: synthesis, cytotoxicity screening against HepG2 and HeLa cell lines and molecular modeling study. Org Med Chem Lett. 2012;2(1):23–33. doi: 10.1186/2191-2858-2-23. DOI: 10.1186/2191-2858-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Razzaghi-Asl N, Miri R, Firuzi O. Assessment of the cytotoxic effect of a series of 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives against human cancer cells. Iran J Pharm Res. 2016;15(3):413–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Razzaghi-Asl N, Firuzi O, Hemmateenejad B, Javidnia K, Edraki N, Miri R. Design and synthesis of novel 3,5-bis-N-(aryl/heteroaryl) carbamoyl-4- aryl-1,4-dihydropyridines as small molecule BACE- 1 inhibitors. Bioorgan Med Chem. 2013;21(22):6893–6909. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.033. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kappe CO, Stadler A. The Biginelli dihydropyrimidine synthesis. Organic Reaction. 2004;63:1–116. DOI: 10.1002/0471264180.or063.01. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassanzadeh F, Sadeghi-Aliabadi H, Jafari E, Sharifzadeh A, Dana N. Synthesis and cytotoxic evaluation of some quinazolinone-5-(4- chlorophenyl)1,3,4-oxadiazole conjugates. Res Pharm Sci. 2019;14(5):408–413. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.268201. DOI: 10.4103/1735-5362.268201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohareb RM, Abdallah AEM, Ahmed EA. Synthesis and cytotoxicity evaluation of thiazole derivatives obtained from 2-amino-4,5,6,7- tetrahydrobenzo[b]thiophene3-carbonitrile. Acta Pharm. 2017;67(4):495–510. doi: 10.1515/acph-2017-0040. DOI: 10.1515/acph-2017-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosseinzadeh L, Aliabadi A, Kalantari M, Mostafavi A, Rahmani Khajouei M. Synthesis and cytotoxicity evaluation of some new 6-nitro derivatives of thiazole-containing 4-(3H)-quinazolinone. Res Pharm Sci. 2016;11(3):210–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Udayakumar V, Gowsika J, Pandurangan A. A novel synthesis and preliminary in vitro cytotoxic evaluation of dihydropyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione derivatives. J Chem Sci. 2017;129(2):249–258. DOI: 10.1007/s12039-017-1223-4. [Google Scholar]