Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Cortical spreading depolarization (CSD) has been linked to poor clinical outcomes in the setting of traumatic brain injury, malignant stroke, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. There is evidence that electrocautery during neurosurgical procedures can also evoke CSD waves in the brain. It is unknown whether blood contacting the cortical surface during surgical bleeding affects the frequency of spontaneous or surgery-induced CSDs. Using a mouse neurosurgical model, the authors tested the hypothesis that electrocautery can induce CSD waves and that surgical field blood (SFB) is associated with more CSDs. The authors also investigated whether CSD can be reliably observed by monitoring the fluorescence of GCaMP6f expressed in neurons.

METHODS

CSD waves were monitored by using confocal microscopy to detect fluorescence increases at the cortical surface in mice expressing GCaMP6f in CamKII-positive neurons. The cortical surface was electrocauterized through an adjacent burr hole. SFB was simulated by applying a drop of tail vein blood to the brain through the same burr hole.

RESULTS

CSD waves were readily detected in GCaMP6f-expressing mice. Monitoring GCaMP6f fluorescence provided far better sensitivity and spatial resolution than detecting CSD events by observing changes in the intrinsic optical signal (IOS). Forty-nine percent of the CSD waves identified by GCaMP6f had no corresponding IOS signal. Electrocautery evoked CSD waves. On average, 0.67 ± 0.08 CSD events were generated per electrocautery episode, and multiple CSD waves could be induced in the same mouse by repeated cauterization (average, 7.9 ± 1.3 events; maximum number in 1 animal, 13 events). In the presence of SFB, significantly more spontaneous CSDs were generated (1.35 ± 0.37 vs 0.13 ± 0.16 events per hour, p = 0.002). Ketamine effectively decreased the frequency of spontaneous CSD waves (1.35 ± 0.37 to 0.36 ± 0.15 CSD waves per hour, p = 0.016) and electrocautery-stimulated CSD waves (0.80 ± 0.05 to 0.18 ± 0.08 CSD waves per electrocautery, p = 0.00002).

CONCLUSIONS

CSD waves are detected with far greater sensitivity and fidelity by monitoring GCaMP6f signals in neurons than by monitoring IOSs. Electrocautery reliably evokes CSD waves, and the frequency of spontaneous CSD waves is increased when blood is applied to the cortical surface. These experimental conditions recapitulate common scenarios in the neurosurgical operating room. Ketamine, a clinically available pharmaceutical agent, can block stimulated and spontaneous CSDs. More research is required to understand the clinical importance of intraoperative CSD.

Keywords: cortical spreading depolarization, CSD, electrocautery, GCaMP6f, mouse model, intraoperative bleeding, ketamine, vascular disorders, traumatic brain injury

Cortical spreading depolarization (CSD) is a phenomenon characterized by dramatic shifts in neuronal ion gradients,9,28 massive cellular depolarization, transient silencing of neuronal activity,18 and changes in local blood flow.4,17,27 CSD in the brain is triggered by a variety of stimuli, including ischemia8,30 and blunt trauma.17 CSD waves propagate through the cortex by extracellular accumulation of K+9,22 and by glutamatergic signaling.9,23,32

The clinical relevance of CSD was unclear until recently. However, the presence of CSD has now been demonstrated in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH),8,17,25 malignant stroke,17 and traumatic brain injury (TBI).17,24 Additionally, the onset of delayed neurological deficits associated with vasospasm in SAH patients has been temporally correlated with bursts of CSD events.8 It is widely hypothesized that CSD waves carry such a high metabolic demand that they impose additional stress on compromised tissue, leading to expanded infarct size.4,30 However, CSD is also thought to underlie migraine auras;28 in this less extreme circumstance of migraine headaches, CSD does not seem to contribute to tissue injury as it does in SAH, stroke, or TBI.1,7,16,17

CSD can also be caused by mechanical pressure1 and electrocautery5 and has been shown to occur in a mouse model of neurosurgery.5 Only one group has described CSD in the setting of intracranial surgery.5,6 Given that CSD is associated with SAH,8 that the brain is exposed to blood during neurosurgical procedures, and that intracranial intraaxial surgeries can require electrocautery of the cortex, we sought to further characterize CSD generation in a mouse neurosurgery model. We set out to accomplish three goals: 1) confirm that electrocautery injury triggers CSD events in a mouse neurosurgery model, 2) test whether surgical field blood (SFB) increases the rate of spontaneous and electrocautery-induced CSD events, and 3) test whether the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blocker ketamine can reduce the number of CSD events that occur with electrocautery or when SFB is present.

Methods

Ethics Statement

All experiments were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Institutes of Health. Experimental procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Care and Use of Animals Committee.

Animals

Transgenic mice expressing the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f in neurons under the CamK2a promoter were used to monitor CSD in the cortex. Forty-four (25 male and 19 female) C57BL/6 mice heterozygous for 129S-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm95.1(CAG-GCaMP6f)Hze/J X 129S6-Tg(Camk2a-cre/ERT2)1Aibs/J (Jackson Lab) were used. Animals were housed in the University of Minnesota laboratory animal facility, allowed ad libitum access to food and water, and kept in a 12/12-hour light/dark cycle. Mice received 1 intraperitoneal (IP) injection per day of 100 mg/kg tamoxifen in sunflower oil for 5 days to induce GCaMP6f expression. Experiments were performed 14 days following the final tamoxifen injection.

Chronic Thinned-Skull Cranial Window

Mice were prepared for chronic awake cortical imaging by creating a thinned-skull cranial window over the left visual cortex under isoflurane anesthesia as described previously.12,26 The skin over the scalp was removed and a metal head bar permanently attached to the skull with cyanoacrylate glue and dental cement. The edges of the cranial window were at 2.0 and 4.0 mm lateral to the sagittal suture and 0.0 and 2.0 mm anterior to the lambdoid suture (Fig. 1). By using a 0.25-mm drill bit, the bone was shaved down through the cancellous layer, leaving the inner table exposed. Animals recovered for 3–5 days after this procedure before they were used for experiments.

FIG. 1.

Electrocautery mouse model of neurosurgery. A 2 × 2–mm thinned-skull cranial window was created on the right side of the head, with the medial border of the window approximately 2 mm from the sagittal suture and the posterior border of the window approximately 0 mm from the lambdoid suture. A burr hole was then drilled 1 mm anterior to the cranial window, approximately at the center of the anterior border of the window, with subsequent durotomy. Through this burr hole, tail vein blood could be applied to the cortical surface and/or the cortex could be cauterized with bipolar electrocautery. During experiments, the mouse was fixed to a head bar attached to a treadmill under the microscope objective. Drawing by Pei-Pei Chiang; used with permission.

On the day of experimentation, while the mouse was under isoflurane anesthesia, a small burr hole and durotomy were created 1.0 mm anterior to the cranial window and roughly in the center of the medial-lateral axis (Fig. 1). The site of the burr hole along the medial-lateral axis was chosen to avoid any large surface blood vessels to minimize risk of bleeding. The burr hole was created using a 0.25-mm drill bit and the dura was gently perforated and stripped from the cortical surface with a 30-gauge needle. Bleeding from this procedure was minimal; in cases with significant bleeding, animals were not used for experiments. The burr hole site was used to access the cortical surface for electrocautery with bipolar forceps electrodes (Fig. 1).

Microscopy

Once the mouse fully recovered from isoflurane anesthesia, it was placed under a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1000) with the head bar screwed into posts and the feet resting on a treadmill. The mouse walked at will on the treadmill. CSD waves were monitored in two ways. The intrinsic optical signal (IOS) of the cortex was monitored with reflectance microscopy at 559 nm. Simultaneously, GCaMP6f fluorescence from cortical neurons was monitored with confocal microscopy at 488 nm. The cortical surface was viewed through the thinned-skull window with a 4× dry objective. During each trial 250 images were acquired over 410 seconds. Electrocautery and nonelectrocautery trials were alternated during a recording session, which lasted for 50 to 250 minutes.

Electrocautery

Electrocautery was performed with a DRE Citadel 180 Electrosurgical Unit designed for small-animal surgery using 3.5-mm curved reusable bipolar forceps electrodes (0.5-mm tip). The bipolar electrodes were positioned with a micromanipulator and lowered through the burr hole to the cortical surface. A period of 7 minutes was allowed to pass before initiation of confocal monitoring, in order to minimize the chance of capturing any CSD episodes that were triggered by the burr hole procedure or by contact of the electrode tips with the cortical surface. Each electrocautery event had a duration of 1 second, with an electrosurgical unit setting of Micro 5. The bipolar electrodes were lowered approximately 150 μm after each cauterizing event to ensure that the electrodes maintained contact with the cortical surface.

Surgical Field Blood

Blood was applied to the cortical surface though the burr hole to determine whether CSD events occur with greater frequency when blood is present in the surgical field. At the start of an experiment, 10 μl of venous blood was taken from the tail vein of the mouse and applied into the burr hole after positioning the bipolar electrodes within the hole. Additional blood was applied into the burr hole between trials if the blood in the hole dried out.

Ketamine

CSD events are heavily dependent on glutamate signaling.9,23,32 Ketamine, an NMDA receptor antagonist that has been implicated as an effective CSD blocker,11 was administered to test whether it could reduce or eliminate CSD events in response to electrocautery in the presence of SFB. The peak ketamine effect occurs approximately 20 minutes after administration.19 Therefore, 25 mg/kg IP ketamine was administered 40 minutes prior to imaging and again 10 minutes prior to imaging to maximize plasma ketamine concentrations. Given ketamine’s short half-life, 25 mg/kg ketamine was re-administered every 30 minutes for the duration of the experiment.

Control Groups

Three separate control experiments were conducted. In the first control group, CSD events were monitored through the thinned-skull window without electrocautery stimulation and before a burr hole was drilled. In the second control group, the burr hole was drilled, the dura was removed, the bipolar electrodes were lowered into the hole, and the mice were then monitored for CSD events, but no electrocautery stimulation was performed. In the third control group, the procedure was similar to that performed in the second group, except that SFB was added to the cortical surface in the burr hole after the bipolar electrodes were placed in the burr hole. In every animal, a period of 7 minutes was allowed to elapse prior to the initiation of confocal monitoring to avoid capturing spontaneous CSD waves due to cranial manipulation and mouse handling.

Analysis

CSD events were detected from image stacks that were processed using a custom MATLAB (MathWorks) routine to highlight changes in IOS brightness and GCaMP6f Ca2+ florescence (Fig. 2). Images were spatially averaged using a Gaussian blur, and changes in intensity were calculated by subtracting the mean of the previous 20 frames from each frame. The vast majority of electrocautery-induced CSD waves occurred within 82 seconds of an electrocautery event. Thus, electrocautery-induced CSD waves were defined as any wave that occurred within 82 seconds after an electrocautery event. Spontaneous CSD waves were defined as any wave that occurred before electrocautery or 82 seconds or more after electrocautery (Fig. 3).

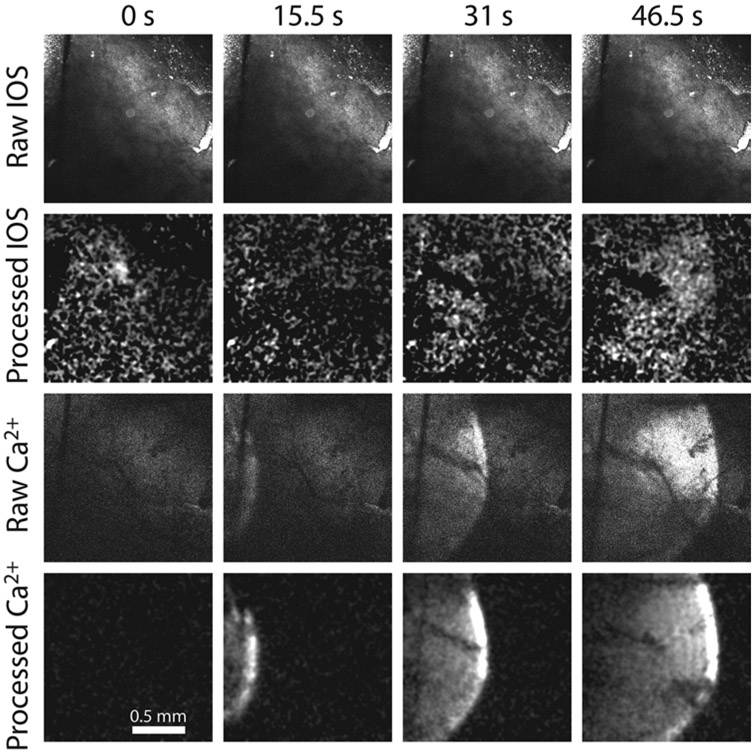

FIG. 2.

Detecting CSD with GCaMP6f fluorescence is superior to detecting CSD with IOS. Image frames are displayed at 4 different time points from a single trial in which GCaMP6 and IOS were monitored simultaneously while a CSD event was elicited with electrocautery at time = 0 seconds (s). The CSD wave in the Raw IOS series could not be detected. However, when the raw image stack was processed using a custom MATLAB routine to highlight changes in signal brightness, the CSD became evident (Processed IOS). Meanwhile, the CSD wavefront during the same trial could be clearly observed in the raw GCaMP6f fluorescence signal (Raw Ca2+) and was further enhanced after image processing (Processed Ca2+).

FIG. 3.

Most electrocautery-evoked CSD waves occur within 82 seconds of electrocautery. Histograms representing the distribution of the number of CSD events after electrocautery in the No SFB group (A), the SFB group (B), and the SFB group that was treated with ketamine (SFB+KET) (C). Electrocautery occurred at time 0. Most electrocautery-evoked CSD waves occurred within 82 seconds of electrocautery. The widened distribution of CSD events in the SFB group is thought to represent the observation of increased spontaneous CSD waves in that group.

Numerical data were analyzed in Excel (Microsoft) and Origin 2018 (OriginLab). Data are presented in dot plots with superimposed bar graphs indicating the mean of the group, with error bars representing SEM. Data are presented in the text as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was set at an alpha of 0.05 and comparisons between groups were made using one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey Honest Significant Difference test. For all experimental groups, n = 8 animals, except the groups of control mice that underwent the thinned-skull window procedure with or without receiving a burr hole, for which n = 6 animals. In the control mice for which SFB was added to the burr hole, n = 8 for control experiments.

Results

Cortical electrocautery has previously been shown to evoke CSD waves.5 In our study, we validated this electrocautery neurosurgical model and tested the hypothesis that SFB results in more frequent CSD events. The cortical surface of awake mice was viewed with confocal microscopy through a thinned-skull cranial window over the visual cortex. Bipolar electrocautery electrodes lowered through a small burr hole in the skull and touching the cortical surface were used to evoke CSD events.

CSD Waves Are More Reliably Detected by Monitoring Calcium Increases in Neurons Than by Monitoring IOS

CSD events can be effectively monitored by measuring GCaMP6 fluorescence in neurons.9

We used transgenic mice expressing the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f in neurons under the CamKII promoter to monitor CSD. Few studies have used genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators to monitor CSD, and in order to validate this technique, we used concurrent IOS intensity measurements and GCaMP6f fluorescence measurements to monitor CSD (Fig. 2). We found that GCaMP6 had far greater sensitivity for identifying CSD events, even when IOS images were processed to increase their contrast. Every CSD wave detected by IOS was also detected with GCaMP6f imaging, but 78 of 160 CSD waves (49%) identified by GCaMP6f had no corresponding IOS signal. When the IOS and GCaMP6 signals were analyzed for each wave, there was no difference in CSD latency (19.7 ± 1.3 vs 19.9 ± 3.4 seconds) or velocity (3.46 ± 0.17 vs 3.46 ± 0.16 mm/min) between the two imaging methods. Given the superiority of GCaMP6 signals in detecting CSD, we performed the rest of our experiments using only GCaMP6f fluorescence to monitor CSD.

Cortical Electrocautery Reliably Evokes CSD Waves

We reliably observed CSD waves when the cortical surface was electrocauterized in our mouse model of neurosurgery. Histograms representing the distribution of the number of CSD events after electrocautery are shown in Fig. 3. On average, 0.67 ± 0.08 waves occurred for each electrocautery event (Fig. 4A). CSD waves were always initiated outside the cranial window. Based on the concentric spread of the waves, they were initiated at or near the site of electrocautery. The latency from onset of electrocautery to the wavefront appearing in the imaging field was 19.9 ± 3.4 seconds (Figs. 3 and 4C). The average velocity of electrocautery-induced CSD waves was 3.46 ± 0.16 mm/min (Fig. 4E).

FIG. 4.

Frequency, latency, and velocity of CSD in the mouse electrocautery model. A: Electrocautery without SFB elicited CSD in the mouse cortex (No SFB group) at an average rate of 0.67 ± 0.08 waves per stimulus (stim). In the presence of SFB (SFB group), 0.80 ± 0.05 CSD waves occurred per stimulus (p = 0.186). However, in SFB mice treated with ketamine (SFB+KET group), the rate of electrocautery-induced waves was decreased (0.18 ± 0.08) compared to the rate in the animals in the No SFB and SFB groups (p = 0.0005 and p = 0.00002, respectively). B: In cortexes previously electrocauterized, the average rate of spontaneous CSD waves in the SFB group was 1.35 ± 0.37 events per hour. This rate was significantly higher than the rate in the No SFB group (0.13 ± 0.16, p = 0.002). Mice in the SFB+KET group showed reduced spontaneous CSD waves in SFB trials compared to SFB group mice that did not receive ketamine (0.36 ± 0.15 events per hour, p = 0.016). For cortexes that did not receive electrocautery, no waves were generated in trials in control mice that underwent the thinned-skull window procedure without a burr hole (Without burr hole) (0.00 ± 0.00). This result was not significantly different from that for mice with no electrocautery in the Burr hole group (0.45 ± 0.25 events per hour, p = 0.11) or in the Burr hole+SFB group (0.38 ± 0.26 events per hour, p = 0.25). C: In the mice with no electrocautery in the Burr hole+SFB group, the occurrence of spontaneous CSD waves did not vary as a function of exposure time to SFB. CSD events occurred randomly over 180-minute trials. D: For CSD wave latency, no statistically significant difference was observed from the time of electrocautery between the No SFB (19.9 ± 3.4 seconds), SFB (23.7 ± 3.5 seconds), and SFB+KET (26.5 ± 5.0) groups (p = 0.21). E: For wave velocity, when CSD waves were elicited by electrocautery (Stim Waves), the average CSD velocity in the No SFB group was 3.46 ± 0.16 mm/min, while in the SFB group it was 3.51 ± 0.19 mm/min (p = 0.99). The average CSD velocity in the SFB+KET group was 1.87 ± 0.13 mm/min, significantly less than that for the SFB group, which was not treated with ketamine (p = 0.0002). When CSD events occurred spontaneously (Spon Waves), there was no difference in CSD velocity between the No SFB (3.2 ± 0.27 mm/min), SFB (3.47 ± 0.27 mm/min), Burr hole (3.81 ± 0.32 mm/min), and Burr hole+SFB groups (3.87 ± 0.34 mm/min); however, ketamine significantly reduced velocity in the SFB+KET group (1.7 ± 0.21 mm/min, p = 0.0009). For all groups, n = 8 animals, except the control Burr hole and Without burr hole mice (all of which underwent the thinned-skull window procedure), for which n = 6 animals. Cautery = electrocautery. *Statistically significant at an alpha of 0.05.

We hypothesized that repeated electrocautery at the same cortical site would eventually result in enough tissue damage so that subsequent electrocautery would not elicit additional waves. However, we found that electrocautery could be repeated many times to reliably produce CSD waves. The maximum number of electrocautery-induced CSD events elicited in 1 animal was 13, and the average was 7.9 ± 1.3 events.

Spontaneous CSD Waves in the Absence of Electrocautery

Occasionally, spontaneous CSD waves were observed independent of electrocautery. These waves occurred infrequently; they were only seen in 2 out of 8 animals. We hypothesized that these waves occurred in response to injury from the burr hole. Indeed, no spontaneous waves were observed in animals that underwent the thinned-skull window procedure without receiving a burr hole, while 0.45 ± 0.26 CSD events per hour occurred in mice that underwent both the thinned-skull window and burr hole procedure (p = 0.11) (Fig. 4B). Comparison of the number of spontaneous CSD waves in mice with burr holes that underwent electrocautery to the number in mice that received a burr hole but did not undergo electrocautery revealed no statistically significant difference in the average number of spontaneous CSD events per hour (0.13 ± 0.16 vs 0.44 ± 0.26 events, p = 0.21) (Fig. 4B). (Spontaneous waves in animals that underwent electrocautery were defined as waves that occur 82 seconds or more after an electrocautery event, as outlined in the Methods.)

Together, these data suggest that the burr hole procedure is relatively benign and does not contribute to risk of CSD in a statistically significant manner. Likewise, skull thinning to produce a cranial window is not irritating to the underlying tissues. These data also suggest that electrocautery of the cortex does not injure the brain in a way that leads to spontaneous recurrent CSD events.

Blood at the Surgical Site Increases Spontaneous CSD Waves

Since SAH is a well-known trigger for CSD waves, we asked whether blood at the surgical site (site of electrocautery) affected the frequency of spontaneous and electrocautery-induced CSD waves. We applied 10 μl of tail vein blood from the mouse to the burr hole site. Contrary to expectations, SFB did not result in a significant increase in electrocautery-induced CSD waves: 0.80 ± 0.05 CSD waves/electrocautery stimulus occurred in the presence of blood, while 0.67 ± 0.08 CSD waves/electrocautery stimulus occurred in the absence of SFB (p = 0.186) (Fig. 4A). There were no statistically significant differences in latency (Fig. 4D) or velocity (Fig. 4E) of electrocautery-induced CSD waves in the presence or absence of SFB.

In contrast, we found that SFB did increase the rate of spontaneous CSD events that occurred in the minutes after the cortex had been cauterized. In the presence of SFB, spontaneous CSD waves occurred at 1.35 ± 0.37 events per hour, a significantly higher rate than the frequency without blood (0.13 ± 0.16, p = 0.002) (Fig. 4B).

We also tested whether SFB increased the rate of spontaneous CSD events in the absence of prior electrocautery. SFB did not result in an increase in spontaneous CSD waves: 0.38 ± 0.26 CSD waves per hour occurred in the presence of blood, while 0.45 ± 0.25 CSD waves per hour occurred in the absence of SFB (p = 0.85) (Fig. 4B). We tested whether the duration of SFB exposure affected the rate of CSD wave generation. The occurrence of CSD waves was not affected by the duration of exposure to SFB (Fig. 4C).

The rate of spontaneous waves in animals that underwent electrocautery in the absence of SFB (0.13 ± 0.16 waves per hour) was not statistically different from the rate of spontaneous CSDs in thinned-skull window controls (without burr hole) (0.00 ± 0.00 CSD events per hour, p = 0.23), in control animals with a burr hole that did not undergo electrocautery (0.45 ± 0.25 CSD events per hour, p = 0.21), and in control animals with a burr hole with SFB that did not undergo electrocautery (0.38 ± 0.26 CSD events per hour, p = 0.38) (Fig. 4B). To summarize, the rate of spontaneous CSD waves is increased in cauterized cortex only when SFB is present.

Ketamine Reduces the Frequency of Stimulated and Spontaneous CSD Waves and Decreases CSD Wave Velocity

Ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist and has been shown to effectively inhibit CSD waves in a variety of CSD model systems.3,10,11,24,29 We tested whether ketamine reduced the frequency of electrocautery-induced CSD events as well as spontaneous CSD events.

We found that IP ketamine reduced the number of CSD waves triggered by electrocautery in the presence of SFB by 77.5%. Ketamine-treated mice experienced 0.18 ± 0.08 CSD waves per electrocautery while mice that did not receive ketamine had 0.80 ± 0.05 CSD waves per electrocautery (p = 0.00002) (Fig. 4A). Ketamine also significantly reduced CSD wave velocity from 3.51 ± 0.19 mm/min in non-ketamine–treated animals to 1.87 ± 0.13 mm/min in ketamine-treated mice (p = 0.0002) (Fig. 4E). The average latency to CSD wave generation in ketamine-treated SFB animals was not significantly different from that of non–ketamine-treated SFB animals (26.5 ± 5.0 vs 23.7 ± 3.5 seconds, respectively) or from no SFB animals (19.9 ± 3.4 seconds, p = 0.21) (Fig. 4D). We also found that ketamine reduced the average number of spontaneous waves per hour in the presence of SFB from 1.35 ± 0.37 to 0.36 ± 0.15 (p = 0.016) (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

Our study confirms a previous report that electrocautery at the surface of the cortex induces CSD waves.5 In addition, we demonstrated, to our knowledge for the first time, that SFB in an animal model of neurosurgery increases spontaneous CSD events during neurosurgical procedures. This finding is particularly notable since blood-induced CSD has not previously been reported in a mouse model. We found that spontaneous CSD waves increased 10-fold following the addition of SFB to the surface of the cortex in brains that had previously been cauterized. However, SFB does not increase the occurrence of CSD events in cortexes not previously exposed to electrocautery. Nor does the duration of SFB exposure change the rate of CSD generation.

In previous studies, it was shown that subdural blood2 and subarachnoid blood4,8,17 from CNS injury are associated with CSD waves. We found that significant neurological compromise is not necessary for spontaneous CSD events to occur in the presence of blood; it is sufficient to apply a small volume of venous blood to the cortical surface. One study reported the occurrence of CSD waves in patients during elective neurosurgical procedures6 but did not attempt to correlate CSD events with bleeding or electrocautery due to the significant practical limitations of recording CSD in the operating room. Our findings of increased CSD with SFB offer a specific risk factor for intraoperative CSD.

The occurrence of CSD during surgical procedures could potentially result in brain damage from loss of neurons as repetitive CSD has been associated with neuronal death,13,23 poor clinical outcomes,25 and neurological deficits from secondary ischemic infarcts after SAH.8 The clinical implications of our results also rest on our finding that ketamine reduces both electrocautery-induced and spontaneous CSD waves seen with SFB. These data are consistent with previous reports that ketamine significantly reduces the incidence of CSD in a dose-dependent manner in animal models3,10 and in patients in the intensive care unit.24 Additionally, experiments in rats found that dexmedetomidine and isoflurane suppress CSD waves compared to propofol and pentobarbital,15 though the ability of these agents to reduce CSD in humans has not been tested. Taken together, these observations suggest that pharmacotherapies already in clinical use could be used to augment neuroanesthesia to limit CSD during neurosurgery.

We did not explore the mechanism of CSD wave generation in the setting of SFB, but wave generation could be due to release of K+ or reactive oxygen species produced by blood breakdown. Blood hemolysis is known to increase K+ levels in venipuncture samples.21 Applying K+ to nervous tissue or increasing oxidative stress has been shown to induce CSD waves.20,22,23,28,32

Our study validates a previously published model of electrocautery as a reliable method of inducing CSD events.5 In that study, Carlson et al. used electrocautery of the mouse cortex while measuring CSDs with electrophysiology and optical imaging techniques. While Carlson et al. limited electrocautery to a single stimulus per cortical site, we electrocauterized a single cortical area multiple times. Importantly, we observed that CSD events could be reliably triggered with repeated electrocautery at the same location, with 1 mouse exhibiting 13 evoked CSD waves. We had hypothesized that electrocautery would result in cortical necrosis from thermal injury, thereby limiting CSD initiation after a small number of electrocautery stimuli. But this was not the case. We also believed that electrocautery-induced cortical injury would increase the frequency of spontaneous CSD waves, just as ischemic injury results in repeated CSDs that originate from the peri-infarcted tissue.30 Surprisingly, this proved incorrect. Our observations demonstrate that not all cortical injuries increase the risk of CSD waves.

CSD is well known to cause changes in IOS due to cell swelling and changes in hemoglobin oxygenation.20,28,29,31 Only one study has investigated CSD by monitoring Ca2+ with genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators.9 In that report, GCaMP6f was expressed in mouse neurons after viral vector delivery and CSD was induced with KCl application to the brain through a small burr hole. The fluorescence signal at the CSD wavefront was found to closely correlate temporally with a negative shift in direct current (DC) potential and increased extracellular K+. This finding is not surprising, as the depolarization and K+ responses are indicative of massive neuronal depolarization, which is accompanied by increased cytoplasmic Ca2+.

We found that CSD waves were detected and characterized with much greater sensitivity and fidelity when the responses were monitored by measuring changes in neuronal Ca2+ compared to measuring the IOS from the cortex. A full 49% of CSD events detected by monitoring GCaMP6f could not be detected with the IOS. It was also much easier to detect the spatial distribution of the CSD event by monitoring neuronal Ca2+ than by measuring the IOS. Thus, mice expressing GCaMP in neurons is the preparation of choice when characterizing CSD in animal experiments.

One potential limitation of our study was that experiments were performed on awake mice, which does not necessarily reflect the clinical scenario in the operating room. Most intraaxial cranial surgeries are performed in patients under anesthesia, and some commonly used anesthetics and sedatives have been shown to inhibit CSD.3,10,11,15,24 This finding suggests that wakefulness may lower the threshold for CSD initiation. However, patients must occasionally be awakened during surgery for intraoperative functional localization of eloquent brain areas.14 These situations most frequently arise in the setting of tumor resections, and patients often remain awake during a portion of the resection. Our model reflects this particular clinical situation well.

A second shortcoming of our study applies to CSD investigations in general: the clinical significance of CSD events is unclear. On the one hand, the correlation between metabolic disturbances and delayed neurological deficits during CSD in the setting of major acute neurological pathology is convincing.8,17,25 Clinical focal neurological deficits correlate temporally with clustered CSD waves and subsequent imaging demonstrates ischemic infarcts in patients.8 However, it is not clear whether CSD episodes that occur without major brain injury or in a setting of controlled brain injury, such as during tumor resections, external ventricular drain placement, or other neurosurgical interventions, are equally deleterious. Several animal studies have reported increased cortical cell death mediated by apoptotic mechanisms after induction of repetitive CSD in healthy rats.13 On the other hand, a study that identified intraoperative CSDs during elective neurosurgical cases did not find any associated negative clinical outcomes or evidence of injury on postoperative imaging.6 Thus, it remains to be determined whether intraoperative CSDs impose clinical risk.

Conclusions

Using an awake, cortical mouse model of neurosurgery, we demonstrated that SFB increases the frequency of spontaneous CSD wave generation, a finding not previously described. We also found that electrocautery of the cortical surface reliably elicits CSD waves. Given that intraaxial neurosurgical operations often involve surgical site bleeding, it is of interest that SFB in our model resulted in a greater frequency of spontaneous CSD waves and a trend toward increased electrocautery-induced CSD waves. The mechanism of this enhancement of CSD generation is unclear, but could be due to the same cellular and molecular events that promote CSD in SAH. It remains to be determined whether intraoperative CSD results in cortical injury. Overall, these findings open an interesting avenue for the study of CSD and its relevance to the practice of neurosurgery.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health award number UL1TR000114 (to Anja I. Srienc) and the National Eye Institute awards R01EY026514 and R01EY026882 (to Eric A. Newman). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CSD

cortical spreading depolarization

- IOS

intrinsic optical signal

- IP

intraperitoneal

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- SAH

subarachnoid hemorrhage

- SFB

surgical field blood

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

References

- 1.Akerman S, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ: Mechanically-induced cortical spreading depression associated regional cerebral blood flow changes are blocked by Na+ ion channel blockade. Brain Res 1229:27–36, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alessandri B, Tretzel JS, Heimann A, Kempski O: Spontaneous cortical spreading depression and intracranial pressure following acute subdural hematoma in a rat. Acta Neurochir Suppl 114:373–376, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amemori T, Bures J: Ketamine blockade of spreading depression: rapid development of tolerance. Brain Res 519:351–354, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayata C, Lauritzen M: Spreading depression, spreading depolarizations, and the cerebral vasculature. Physiol Rev 95:953–993, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson AP, Carter RE, Shuttleworth CW: Vascular, electrophysiological, and metabolic consequences of cortical spreading depression in a mouse model of simulated neurosurgical conditions. Neurol Res 34:223–231, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson AP, Shuttleworth CW, Mead B, Burlbaw B, Krasberg M, Yonas H: Cortical spreading depression occurs during elective neurosurgical procedures. J Neurosurg 126:266–273, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SP, Ayata C: Spreading depression in primary and secondary headache disorders. Curr Pain Headache Rep 20:44, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dreier JP, Woitzik J, Fabricius M, Bhatia R, Major S, Drenckhahn C, et al. : Delayed ischaemic neurological deficits after subarachnoid haemorrhage are associated with clusters of spreading depolarizations. Brain 129:3224–3237, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enger R, Tang W, Vindedal GF, Jensen V, Helm PJ, Sprengel R, et al. : Dynamics of ionic shifts in cortical spreading depression. Cereb Cortex 25:4469–4476, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernándéz-Cáceres J, Macias-González R, Brozek G, Bures J: Systemic ketamine blocks cortical spreading depression but does not delay the onset of terminal anoxic depolarization in rats. Brain Res 437:360–364, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hertle DN, Dreier JP, Woitzik J, Hartings JA, Bullock R, Okonkwo DO, et al. : Effect of analgesics and sedatives on the occurrence of spreading depolarizations accompanying acute brain injury. Brain 135:2390–2398, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holtmaat A, Bonhoeffer T, Chow DK, Chuckowree J, De Paola V, Hofer SB, et al. : Long-term, high-resolution imaging in the mouse neocortex through a chronic cranial window. Nat Protoc 4:1128–1144, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahanbazi Jahan-Abad A, Alizadeh L, Sahab Negah S, Barati P, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Meuth SG, et al. : Apoptosis following cortical spreading depression in juvenile rats. Mol Neurobiol 55:4225–4239, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn E, Lane M, Sagher O: Eloquent: history of a word’s adoption into the neurosurgical lexicon. J Neurosurg 127:1461–1466, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kudo C, Toyama M, Boku A, Hanamoto H, Morimoto Y, Sugimura M, et al. : Anesthetic effects on susceptibility to cortical spreading depression. Neuropharmacology 67:32–36, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauritzen M: On the possible relation of spreading cortical depression to classical migraine. Cephalalgia 5 (Suppl 2):47–51, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauritzen M, Dreier JP, Fabricius M, Hartings JA, Graf R, Strong AJ: Clinical relevance of cortical spreading depression in neurological disorders: migraine, malignant stroke, subarachnoid and intracranial hemorrhage, and traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31:17–35, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leao AA: Further observations on the spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol 10:409–414, 1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Martinez-Lozano Sinues P, Dallmann R, Bregy L, Hollmén M, Proulx S, et al. : Drug pharmacokinetics determined by real-time analysis of mouse breath. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 54:7815–7818, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Netto M, Do Carmo RJ, Martins-Ferreira H: Retinal spreading depression induced by photoactivation: involvement of free radicals and potassium. Brain Res 827:221–224, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyirenda MJ, Tang JI, Padfield PL, Seckl JR: Hyperkalaemia. BMJ 339:b4114, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obrenovitch TP, Zilkha E: High extracellular potassium, and not extracellular glutamate, is required for the propagation of spreading depression. J Neurophysiol 73:2107–2114, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadeghian H, Jafarian M, Karimzadeh F, Kafami L, Kazemi H, Coulon P, et al. : Neuronal death by repetitive cortical spreading depression in juvenile rat brain. Exp Neurol 233:438–446, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakowitz OW, Kiening KL, Krajewski KL, Sarrafzadeh AS, Fabricius M, Strong AJ, et al. : Preliminary evidence that ketamine inhibits spreading depolarizations in acute human brain injury. Stroke 40:e519–e522, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakowitz OW, Santos E, Nagel A, Krajewski KL, Hertle DN, Vajkoczy P, et al. : Clusters of spreading depolarizations are associated with disturbed cerebral metabolism in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 44:220–223, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shih AY, Mateo C, Drew PJ, Tsai PS, Kleinfeld D: A polished and reinforced thinned-skull window for long-term imaging of the mouse brain. J Vis Exp (61):3742, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin HK, Dunn AK, Jones PB, Boas DA, Moskowitz MA, Ayata C: Vasoconstrictive neurovascular coupling during focal ischemic depolarizations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26:1018–1030, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somjen GG: Mechanisms of spreading depression and hypoxic spreading depression-like depolarization. Physiol Rev 81:1065–1096, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srienc AI, Biesecker KR, Shimoda AM, Kur J, Newman EA: Ischemia-induced spreading depolarization in the retina. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 36:1579–1591, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Bornstädt D, Houben T, Seidel JL, Zheng Y, Dilekoz E, Qin T, et al. : Supply-demand mismatch transients in susceptible peri-infarct hot zones explain the origins of spreading injury depolarizations. Neuron 85:1117–1131, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu Y, Santos LM, Mattiace LA, Costa ML, Ferreira LC, Benabou K, et al. : Reentrant spiral waves of spreading depression cause macular degeneration in hypoglycemic chicken retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:2585–2589, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou N, Rungta RL, Malik A, Han H, Wu DC, MacVicar BA: Regenerative glutamate release by presynaptic NMDA receptors contributes to spreading depression. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33:1582–1594, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]