Abstract

Background:

Universal 2-child policy was proposed in 2015 in China, but it was still uncertain whether having a second child would have any impacts on maternal health, especially mental health. So, the aim of this study was to compare the incidence of perinatal depression between the first-child women and the second-child women and to describe the patterns of perinatal depression from the first and third trimesters to 6 weeks postpartum.

Methods:

A prospective cohort study was conducted in a university hospital, 969 first-child women and 492 second-child women registered in this hospital from Dec 2017 to Mar 2018 were involved in the study. The Mainland Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was applied to screen perinatal depressive symptoms, while socio-demographic and obstetric data were obtained by self-administered questionnaires. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to compare the risk of depression between 2 groups, and repeated measures of analysis of variances (ANOVAs) were used to determine the EPDS scores of 2 groups across 3 stages.

Results:

The incidence of perinatal depression was 21.78% to 24.87% and 18.29% to 22.15% in the first-child group and the second-child group, respectively. The second-child women were less likely to exhibit depressive symptoms than the first-child women in the first trimester (Adjusted OR = 0.630, 95%CI = 0.457–0.868, P = .005), but no significant difference was found between the 2 groups in the third trimester and at postpartum period. During the whole perinatal period, no significant difference was found in EPDS scores of the first-child group among the three stages. However, the EPDS scores of the second-child group were higher in the first trimester than that at the postpartum period.

Conclusion:

The risk of perinatal depression for the second-child women was no higher than for the first-child women, and the EPDS scores of the second-child women were decreasing during the perinatal period. So couples in West China are recommended to consider having a second child without much worry about its negative effects on mental health under the universal 2-child policy.

Keywords: China, perinatal depression, two-child policy

1. Introduction

One-child policy proposed in 1980[1] was a special family planning policy in China. It restricted most of Chinese couples to have only one child and reduced the birth rate successfully. By 2010, China's total fertility rate had fallen to 1.18, which was far below the population replacement level.[2] Meanwhile, it has also some other benefits, including acceleration of gender equality, increasing of children's well-being, and falling of maternal mortality rate.[3] However, on the other side, the one-child policy has also brought many negative effects, such as accelerating population aging, labor shortages,[4] and the skewed sex ratio, which would threaten economic growth.[5] So 2-child policy was gradually introduced, couples at least one of the partners was an only-child were permitted to have 2 children from November 2013,[6] but by 2015,only 1.45 million (13 2%) of 11 million eligible couples applied for permission to have a second child.[3] In addition, the number of birth did not increase but decreased by 0.32 million in 2015 compared to the previous year.[2] The cost of childcare, age, work status, household income are main reasons preventing them from wanting a second child.[3,7] According to the low uptake, together with appeals from scholars and the media,[3] universal 2-child policy came into effect in China from January 1, 2016,[8] which means all Chinese couples are allowed to have 2 children, and it marks the end of China's one-child policy which has lasted more than three decades.

After 35 years of 1-child policy, most of Chinese families had only 1 child, and they usually focused on their only-child. Now the new policy comes into effect, if they would have a second child, they will confront many problems in coping with the changed family model, such as more stress, more cost, more caretaking, less time in work, et al.[9] So many couples hesitate to have a second child, and it significantly limits the implementation of 2-child policy. It is really still uncertain whether the new policy has any negative impacts on maternal health, including physical and mental health.

Perinatal depression, as a main mental problem in both pregnant and postnatal women, has far-reaching consequences, affecting not only the women but also the birth outcomes,[10] the offspring,[11,12] the partners and family relationships.[13–15] It had been increasingly concerned by clinicians, nurses, community workers and scientists, and a great deal of researches about prenatal and postnatal depression had been done during the past several decades. However, to our knowledge, few large prospective studies about the second-child women's depression status, especially with comparison to the first-child women were concluded after the shift of the policy. Therefore, both the second-child women and the first-child women were involved in this study, their depressive symptoms were followed up from the first trimester of pregnancy to postpartum, and comparisons of perinatal depression were made between 2 groups, aims to explore the impacts of the policy on perinatal maternal mental health and the patterns of depressive symptoms during the whole perinatal period. The results will guide the couples to make decisions whether to have a second baby, help healthcare providers improve their service, and ensure the successful implementation of the 2-child policy in China.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and sample

This is a prospective cohort study, taking “having a second child” as the exposure which means the women who are going to have their first child be involved in the unexposed group (group 1), and the women going to have a second child be involved in the exposed group (group 2), Three times follow-up were taken from the first trimester to postpartum, and depressive symptoms assessment were done every time. In this study, the “first-child women” and “second-child women” meant those who were going to have their first or second child in the family, not their first or second gestation.

Women registered to give birth at a university hospital were recruited to the study from December 2017 to March 2018, and follow-up investigations were taken in the third trimester from April 2018 to July 2018 and at 6 weeks postpartum from August 2018 to December 2018.

This university hospital is the biggest women's and children's hospital in China, it is located in Chengdu, the fourth most populous city in China with a population of more than 14 million people covering an area of 14,335 km2. Many women from Sichuan and other provinces of West China come to this hospital to give birth and more than 10,000 babies were delivered in this hospital per year.

Convenience sampling was used in this study, the inclusion criteria were:

-

(1)

≤13 weeks of gestation at enrolment;

-

(2)

≥18 years old;

-

(3)

have sufficient proficiency in Chinese and can complete the written questionnaires by themselves.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

(1)

still birth or fetal deformities;

-

(2)

already had 2 or more children alive;

-

(3)

personal and family history of psychiatric problems.

2.2. Data collection

All women were invited to participate in the study on the voluntary basis, and their written informed consent for the purpose of research and publication was obtained. The questionnaires were completed by the women themselves in 30 minutes anonymously and confidentially. The first set of data was collected in the first trimester of pregnancy when they came to hospital to register for antenatal care visit, the second in the third trimester of pregnancy (after 28 weeks of gestation according to Chinese standard of pregnancy staging) during routine antenatal follow-up, and the final survey was carried out approximately 6 weeks after childbirth when they came back to have their routine postnatal checkup.

2.3. Measurement

The socio-demographic data were collected in the first time at enrolment in the study by a self-administered questionnaire, which included age, nationality, marital status, educational level, employment status, place of residence, religion, monthly individual income, and inmate. But living with partner and living with parents/ parents-in-law were collected every time as they were more changeable variables.

Obstetrical data were collected at different stages. Gestational weeks, planning of pregnancy were collected in the first trimester; gender expectations and complications during pregnancy were collected in the third trimester; delivery mode, weight of the newborn, the newborn's health status, emotional disturbance and postnatal caregiver were collected at the postpartum follow up.

The Mainland Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was used to screen perinatal depressive symptoms as it has already been validated in China in both prenatal[16,17] and postnatal women[13,18] with good reliability and validity. It is a 10-item self-rating scale, with each item scores 0 to 3, and the total scores range from 0 to 30. The recommended cut-off score is 9.5 with a 78.6% sensitivity and 83.4% specificity, and the area under curve (AUC) is 0.845.[16] The Cronbach's alpha in this study was 0.757 to 0.826, which suggested a good internal consistency.

2.4. Ethics consideration

Ethical approval that complied with the Declaration of Helsinki was obtained from the Ethics Committee of West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University (No. 2019(002)).

2.5. Data analysis

The SPSS statistical software (version 22.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis was carried out to analyze the socio-demographic data, the obstetrical data, depression incidence and the EPDS scores. As there were significant differences between 2 groups’ baseline variables, adjusted odds ratio with its 95% confidence interval were calculated to report the significant differences of risk in perinatal depression between 2 groups. Regarding “depression incidence” as dependent variable, “group” as independent variable, and the baseline variables had statistically significant differences as covariant, to establish regression model. Repeated measures of analysis of variances (ANOVAs) were used to determine the EPDS scores of 2 groups across three stages. The missing data were not filled up in this study. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics of the participants

A total of 1551 women registered in a university hospital were invited to join the study (Fig. 1), of whom 1461 (969 first-child women and 492 second-child women) completed the questionnaires in the first trimester (response rate = 94.20%), and 90 women refused to participate. The retention of women was 945 in the third trimester, including 629 first-child women and 316 second-child women. Although messages were sent to the participants by researchers to attempt to increase the number of returns, only 613 women completed the questionnaires at 6 weeks postpartum, including 438 first-child women and 175 second-child women. The number of women retained throughout the entire 3 times of survey was 454, and the response rate is similar to the previous prospective studies.[19,20] The primary reasons for withdrawal were that they did not come back to the hospital but went to community healthcare centers to have their postnatal checkup, however we did not have enough investigators to follow up in those places. A flow diagram was presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the implementation of the study. Group 1 = the first-child women group, Group 2 = the second-child women group, The arrows to the left or right (“←” or “→”)in the figure meant the explanations to corresponding steps, and the down arrows (“↓”) represented the progress of the steps.

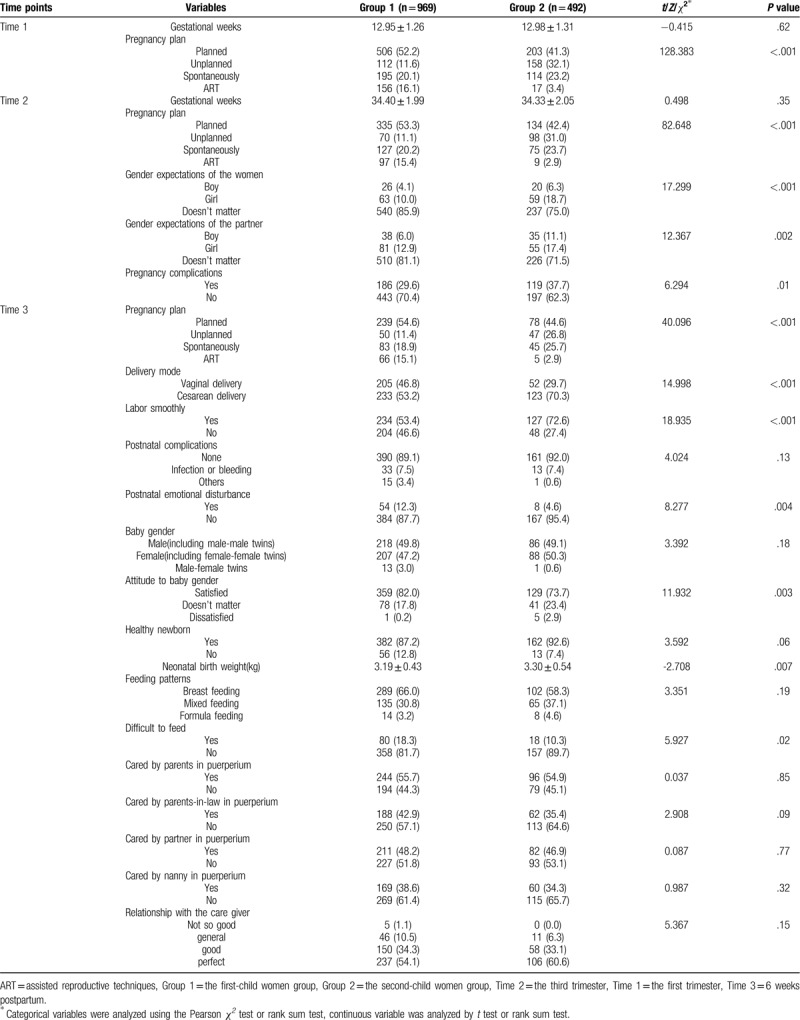

Detailed Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants were summarized in Table 1, and obstetric characteristics in Table 2.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants at three stages of the study.

Table 2.

Obstetrical characteristics of the participants at 3 stages of the studya.

3.2. Comparisons of depressive symptoms between 2 groups

As shown in Table 3, the second-child women were less likely to exhibit depressive symptoms in the first trimester (AOR = 0.630, 95%CI: 0.457–0.868, P = .005) after adjustment of all the significantly different baseline variables shown in Table 1 and Table 2, but 2 groups were equally likely to report depressive symptoms in the third trimester and postpartum.

Table 3.

Comparisons on the risk of depression between 2 groups at 3 stages.

3.3. Patterns of perinatal depressive symptoms

Repeated measures ANOVAs were used to determine the EPDS scores across three stages. As shown in Table 4 and Figure 2, the mean EPDS scores of 2 groups were both changing during the perinatal period. It could be seen from Table 5 that there was no significant difference during the EPDS scores of the first-child group, while there was a significant difference during the EPDS scores of the second-child group (F = 4.124, P = .02). And as shown in Table 6, the EPDS scores of the second-child group were significantly higher in the first trimester than at postpartum (P = .01).

Table 4.

EPDS scores of 2 groups at 3 stages.

Figure 2.

The line graph of EPDS scores in two groups. Time 1 = the first trimester, Time 2 = the third trimester, Time 3 = 6 weeks postpartum, Group 1 = the first-child women group, Group 2 = the second-child women group, EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Group  , Group

, Group  .

.

Table 5.

Repeated measures ANOVAs of EPDS scores at 3 stages in 2 groups.

Table 6.

Pairwise comparisons of EPDS scores in the second-child group (LSD pairwise comparison after the event).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective cohort study making a comparison between the first-child women and the second-child women and exploring the patterns of perinatal depressive symptoms in China. We found that depressive symptoms were common in perinatal women. The second-child women were less likely to exhibit depressive symptoms than the first-child women in the first trimester, but no significant differences were found between them in the third trimester and at postpartum period. For the first-child women, no significant differences were found in EPDS scores during the perinatal period; however, the second-child women's EPDS scores were decreasing gradually from the first trimester to postpartum, lowest at postnatal period and highest in the first trimester.

Similar to other studies, we found that depressive symptoms were prevalent in both prenatal[21] and postpartum period,[22] but lower than some previous studies,[20,23–26] this may be attributed to the fact that most of the women registered in this hospital came from the relatively higher socioeconomic class and easy to get adequate perinatal social support.

Contrary to expectations, with all the baseline variables which had significant differences being adjusted, we did not find higher prevalence of perinatal depressive symptoms in the second-child women, but lower than that of the first-child women in the first trimester(AOR = 0.630, 95%CI:0.457–0.868, P = .005). Similar results were seen by Ayele in a cross-sectional study of 388 pregnant women in Ethiopia.[21] This may be attributed to the fact that the first-child women are lack of experience in coping with pregnancy related problems and more fear of pregnant complications. But Golbasi et al's[27] previous study about 258 pregnant women from 19 primary health care centers in Turkey revealed that the EPDS scores of multiparas were higher than that of primiparas, the possible explanations could be that the multiparas included not only the second-child women but also the third or more, and more children might bring more stress, but the multiparas in our study just means the second-child women, and the family support in China is very strong, the grandparents always help to take care of the children, so the parents do not have so much burden in child care. These findings indicate that having a second child will not increase the risk of the maternal perinatal depressive symptoms, the 2-child policy is a good family planning policy in China and should be promoted by Chinese people.

Consistent with Lau et al's[20] and Takehara et al's[28] studies, it was found that the EPDS scores of the second-child women were decreasing gradually from the first trimester to 6 weeks postpartum in our study. This is likely due to their greater confidence in parenting abilities owing to previous experience, including breastfeeding and child caring.[28] However, the EPDS scores in Takehara et al's[28] study of Japanese women was much lower than that of this study, the main cause may be the differences in national culture and people's characteristics, and Japanese have higher adversity quotient.

As compared to the second-child women, the first-child women did not show a significant change throughout the perinatal period. This finding was consistent with Liou et al's study of 197 women in Taiwan China.[29] As time advances, the stress derived from pregnancy gradually weakens, but new stress such as infant feeding and caring occurs, so the EPDS scores remain stable from antenatal to postpartum.

Since the EPDS scores of the second-child women showed a peak in the first trimester, it is very important for clinicians to screen depressive symptoms early in pregnancy. But for the first-child women, it is necessary to screen perinatal depressive symptoms both early during pregnancy and postpartum. In addition, some non-pharmacological psychological training, such as self-management, mental relaxation techniques, and cognitive behavior programs should be suggested to antenatal intervention, so as to improve women's coping skills and reduce possibility of depressive symptoms.

5. Conclusion

The universal 2-child policy in China does not bring any significant influences in Chinese women's mental health. The second-child women are not more likely to experience perinatal depressive symptoms. On the contrary, they are less likely to exhibit antenatal depressive symptoms in the first trimester. Meanwhile, their depressive symptoms will decrease constantly during the perinatal period. So couples can consider having a second-child without too much worry.

6. Limitations and recommendations

Although a prospective cohort study was conducted and some useful results about the impacts of the 2-child policy had been found, several limitations must be considered in interpreting our findings. First, our participant sample was drawn from only one university hospital, the women registered in this hospital could be identified as a representative group of higher class urban citizens but not representative enough in other populations in China, and multi-center studies should be done in the future. In addition, we just followed up to 6 weeks postpartum, the long term influences of the new policy was still unclear. So longer term longitudinal studies need to be carried out to explore the long-term influences of the 2-child policy.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all of the women participating in the study and all the investigators help collecting the data.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Xiu-Jing Guo.

Data curation: Xue Deng.

Formal analysis: Xue Deng.

Investigation: Jing Chen, Xue Deng.

Methodology: Liang-Zhi Xu.

Project administration: Jing Chen, Jian-Hua Ren.

Resources: Jing Chen, Jian-Hua Ren.

Software: Jian-Hua Ren.

Supervision: Jian-Hua Ren, Liang-Zhi Xu.

Writing – original draft: Xiu-Jing Guo.

Writing – review & editing: Xiu-Jing Guo.

Footnotes

Abbreviation: EPDS = Edinburgh postnatal depression scale.

How to cite this article: Guo XJ, Chen J, Ren JH, Deng X, Xu LZ. Comparisons on perinatal depression between the first-child women and the second-child women in West China under the universal two-child policy: a STROBE compliant prospective cohort study. Medicine. 2020;99:23(e20641).

This study was supported by health and family planning commission of Sichuan province (project No. PJ222).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

- [1].Xinzhong Q. Implementation of China's population policy. China Popul Newsl 1983;1:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].The sixth national census office of the State Council. Major figures on 2010 population census of China: China Statistics Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zeng Y, Hesketh T. The effects of China's universal two-child policy. Lancet 2016;388:1930–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Xu L, Yang F, Sun J, et al. Evaluating family planning organizations under China's two-child policy in Shandong Province. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:2121–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhao Y, Lin J, Shang X, et al. Impact of the universal two-child policy on the workload of community-based basic public health services in Zhejiang Province, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:2289–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cheng PJ, Duan T. China's new two-child policy: maternity care in the new multiparous era. BJOG 2016;123:7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lau BH, Huo R, Wang K, et al. Intention of having a second child among infertile and fertile women attending outpatient gynecology clinics in three major cities in China: a cross-sectional study. Hum Reprod Open 2018;1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Feng W, Gu B, Cai Y. The end of China's one-child policy. Stud Fam Plann 2016;47:83–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schwank SE, Gu C, Cao Z, et al. China's child policy shift and its impact on Shanghai and Hangzhou women's decision-making. Int J Womens Health 2018;10:639–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Liou S, Wang P, Cheng C. Effects of prenatal maternal mental distress on birth outcomes. Women Birth 2016;29:376–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, et al. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2011;14:1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Bunn J, et al. Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness: a cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lau Y, Wang Y, Yin L, et al. Validation of the mainland Chinese version of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in Chengdu mothers. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:1139–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kerstis B, Berglund A, Engström G, et al. Depressive symptoms postpartum among parents are associated with marital separation: A Swedish cohort study. Scand J Public Health 2014;42:660–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cavalcante M, Lamy FF, Franca A, et al. Mother-child relationship and associated factors: Hierarchical analysis of the population base in a Brazilian state capital - BRISA Study. Cien Saude Colet 2017;22:1683–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Xiu-Jing G, Yu-Qiong W, Ying L, et al. Study on the optimal critical value of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in the screening of antenatal depression. Chin J Nurs 2009;44:808–10. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang Y, Guo X, Lau Y, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Mainland Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:813–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yuqiong W, Xiujing G. Study on the critical value of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in puerpera of Chengdu. Chin J Prac Nurs 2009;25:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bakker M, van der Beek AJ, Hendriksen IJM, et al. Predictive factors of postpartum fatigue: a prospective cohort study among working women. J Psychosom Res 2014;77:385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lau Y, Wong DFK, Chan KS. The utility of screening for perinatal depression in the second trimester among Chinese: a three-wave prospective longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2010;13:153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ayele TA, Azale T, Alemu K, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression among women attending antenatal care service at Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. PloS One 2016;11:e155125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chi X, Zhang P, Wu H, et al. Screening for postpartum depression and associated factors among women in China: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol 2016;7:1668–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Muneer A, Minhas FA, Tamiz-ud-Din NA, et al. Frequency and associated factors for postnatal depression. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2009;19:236–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ortiz MR, Gallego BC, Buitron ZE, et al. Prevalence of positive screen for postpartum depression in a tertiary hospital and associated factors. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr 2016;45:253–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Agbaje OS, Anyanwu JI, Umoke P, et al. Depressive and anxiety symptoms and associated factors among postnatal women in Enugu-North Senatorial District, South-East Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health 2019;77:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Aydin N, Inandi T, Karabulut N. Depression and associated factors among women within their first postnatal year in Erzurum province in eastern Turkey. Women Health 2005;41:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Golbasi Z, Kelleci M, Kisacik G, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depression in pregnancy among Turkish women. Matern Child Health J 2010;14:485–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Takehara K, Tachibana Y, Yoshida K, et al. Prevalence trends of pre- and postnatal depression in Japanese women: a population-based longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 2018;225:389–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liou S, Wang P, Cheng C. Longitudinal study of perinatal maternal stress, depressive symptoms and anxiety. Midwifery 2014;30:795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]