Abstract

This retrospective study aimed to explore the benefits and safety of probiotics (live combined Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium granules with multivitamines) for the treatment of children with antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD).

A total of 72 children with AAD were analyzed in this study. Of these, 36 children received routine treatment plus probiotics, and were assigned to a treatment group. The other 36 children underwent routine treatment alone, and were assigned to a control group. Patients in both groups were treated for a total of 7 days. The efficacy and safety were evaluated by duration of diarrhea (days), number of dressings needed daily, abdominal pain intensity, stool consistency (as assessed by Bristol Stool Scale (BSS)), and any adverse events.

After treatment, probiotics showed encouraging benefits in decreasing duration of diarrhea (days) (P < .01), number of dressings needed every day (P < .01), abdominal pain intensity (P < .01), and stool consistency (BSS (3–5), P < .01; BSS (6–7), P < .01). In addition, no adverse events were documented in this study.

The findings of this study demonstrated that probiotics may provide promising benefit for children with AAD. Further studies are still needed to warrant theses findings.

Keywords: antibiotic-associated diarrhea, efficacy, probiotics, safety

1. Introduction

Antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) is a very common disorder that is associated with utilization of many antibiotics.[1–4] Such antibiotics disrupt the colonization resistance of gastrointestinal flora and related overgrowth of bacteria.[5–6] It is defined as diarrhea of at least 3 times loose stools each day up to 2 weeks after the first treatment of antibiotics.[7–9] It has been estimated that about 11% to 40% children who underwent broad spectrum antibiotics experience AAD.[9–13] Several factors are responsible for such condition, including nearly all antibiotics and C. difficile infection.[14–16]

Several studies have reported to use probiotics for the treatment of children with AAD.[17–24] However, there are insufficient data to support probiotics (live combined Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium granules with multivitamines) for the treatment of ADD, although several similar studies reported such intervention may benefit children with diarrhea.[25–30] Therefore, more studies are still needed to further explore the efficacy of probiotics for the treatment of children with AAD. The present study investigated the efficacy and safety of probiotics for the treatment of children with AAD.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the ethics medical committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Jiamusi University. All included subjects provided written informed consent by their guardians.

2.2. Design

This retrospective study included 72 children with AAD from First Affiliated Hospital of Jiamusi University between December 2017 and November 2019. All 72 children were equally assigned to the treatment group (n = 36) and the control group (n = 36) according to the different treatment schedules they received. All children in both groups received routine treatment. In addition, children in the treatment group also received probiotics.

2.3. Patients

All eligible participants aged between 5 and 11 years old were diagnosed as AAD.[31] Patients were excluded if they had other gastrointestinal pathologies, allergy to the study medication, other medications that could affect the results of this study, and took laxatives. There were no limitations to the race, country and gender in this study.

2.4. Treatment schedule

All 72 patients in both groups received routine treatment, including fluids replenishment to prevent dehydration and to balance water and electrolyte disorders.

In addition, 36 patients in the treatment group received probiotics (live combined Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium granules with multivitamines, Beijing Hanmei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (S20020037)),[32–33] 1 g/pack, 1 pack each time, twice daily for a total of 7 days.

2.5. Outcome measurements

The primary outcomes were duration of diarrhea (days), and number of dressings needed every day.

The secondary outcomes were abdominal pain intensity (as measured by visual analog scale, varies from 0 (no pain), to 10 (the worst pain)),[34–35] stool consistency (as assessed by Bristol Stool Scale (BSS), including 7 types as follows: type 1 to 2 indicates constipation; type 3 to 5 suggests normal stools; and type 6 to 7 means liquid stool[36–37]), and any adverse events.

2.6. Statistical analysis

This study utilized SAS package (Version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) to analyze all baseline and outcome data. We used t test or Wilcoxon test to analyze continuous data, and applied Pearson chi-square test or Fisher exact test to analyze discontinuous data. The value of P < .05 was defined as having statistical significance.

3. Results

The comparison of baseline characteristics of patients in both groups is shown in Table 1. There are not significant differences regarding the baseline characteristics between two groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between 2 groups.

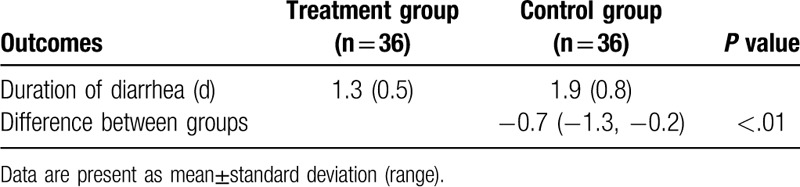

The results exerted that patients in the treatment group achieved more benefit in duration of diarrhea (days) (P < .01, Table 2), number of dressings needed every day (P < .01, Table 3), abdominal pain intensity (P < .01, Table 4), and stool consistency (BSS (3–5), P < .01; BSS (6–7), P < .01, Table 5), than patients in the control group.

Table 2.

Comparison of duration of diarrhea between 2 groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of number of dressings needed daily between 2 groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of abdominal pain intensity between two groups.

Table 5.

Comparison of stool consistency between two groups.

In addition, no expected or unexpected adverse events were recorded in both groups in this study.

4. Discussion

Although several studies have investigated the efficacy and safety of probiotics for the treatment of children with AAD,[17–24] few data are available to specifically support the efficacy and safety of probiotics for the treatment of Chinese children with AAD. This retrospective study explored the benefits and safety of probiotics for the treatment of Chinese children with AAD. Its results exerted promising benefits in Chinese children with AAD.

The findings of this study are partly consistent with previous studies.[25–30] In this study, our results found that probiotics showed promising benefits in children with AAD in reducing duration of diarrhea, number of dressings needed daily, abdominal pain intensity, and enhancing stool consistency. In addition, this study did not identify any adverse events after treatment. The results of this study indicated that probiotics may benefit Chinese children with AAD.

There are several limitations in this study. First, this retrospective study did not apply randomization procedure to assign patients to the treatment and control groups, because this study only collected data from previously completed patient case records. Second, all patient cases were collected from 1 center of First Affiliated Hospital of Jiamusi University, which may affect its generalization to the other hospitals in China. Third, this study evaluated the efficacy and safety of probiotics for the treatment of children with AAD within 7-day treatment period, and no follow-up measurement was assessed. Fourth, the sample size was quite small in this study, which may impact our findings. Finally, this study is a retrospective study, so it has an intrinsic limitation. Therefore, further studies should avoid above limitations.

5. Conclusion

The findings of this study found that probiotics may benefit children with AAD. However, future studies are still needed to verify the results of this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Xue Rui.

Data curation: Xue Rui, Shu-xia Ma.

Formal analysis: Shu-xia Ma.

Investigation: Shu-xia Ma.

Methodology: Xue Rui, Shu-xia Ma.

Project administration: Shu-xia Ma.

Resources: Xue Rui, Shu-xia Ma.

Software: Xue Rui.

Supervision: Shu-xia Ma.

Validation: Xue Rui, Shu-xia Ma.

Visualization: Xue Rui, Shu-xia Ma.

Writing – original draft: Xue Rui, Shu-xia Ma.

Writing – review & editing: Xue Rui, Shu-xia Ma.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AAD = antibiotic-associated diarrhea, BSS = Bristol stool scale.

How to cite this article: Rui X, Ma Sx. A retrospective study of probiotics for the treatment of children with antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Medicine. 2020;99:23(e20631).

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from a third party, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the third party.

References

- [1].Bartlett JG. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2002;346:334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Silverman MA, Konnikova L, Gerber JS. Impact of antibiotics on necrotizing enterocolitis and antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2017;46:61–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Plotnikova EY, Zakharova YV. Place of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Ter Arkh 2015;87:127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mantegazza C, Molinari P, D’Auria E, et al. Probiotics and antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children: a review and new evidence on Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG during and after antibiotic treatment. Pharmacol Res 2018;128:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Högenauer C, Hammer HF, Krejs GJ, et al. Mechanisms and management of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:702–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jabbar A, Wright RA. Gastroenteritis and antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Prim Care 2003;30:63–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bartlett JG. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 1992;15:573–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2002;346:334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cai J, Zhao C, Du Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of probiotics for antibiotic-associated diarrhea: systematic review with network meta-analysis. United European Gastroenterol J 2018;6:169–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McFarland LV. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea: epidemiology, trends and treatment. Future Microbiol 2008;3:563–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Goldenberg JZ, Lytvyn L, Steurich J, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;Cd004827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hempel S, Newberry SJ, Maher AR, et al. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;307:1959–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nasiri MJ, Goudarzi M, Hajikhani B, et al. Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection in hospitalized patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaerobe 2018;50:32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schröder O, Gerhard R, Stein J. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Z Gastroenterol 2006;44:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Alam S, Mushtaq M. Antibiotic associated diarrhea in children. Indian Pediatr 2009;46:491–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Luzina EV, Lareva NV. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea in clinical practice. Ter Arkh 2013;85:85–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Esposito C, Roberti A, Turrà F, et al. Frequency of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and related complications in pediatric patients who underwent hypospadias repair: a comparative study using probiotics vs Placebo. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2018;10:323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Uspenskiĭ IuP, Zakharenko SM, Fominykh IuA. Perspective applications of multi-species probiotics in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Eksp Klin Gastroenterol 2013;2:54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Szajewska H, Weizman Z, et al. ESPGHAN Working Group on Probiotics and Prebiotics. Inulin and fructo-oligosaccharides for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children: report by the ESPGHAN Working Group on Probiotics and Prebiotics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:828–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stein GY, Nanim R, Karniel E, et al. Probiotics as prophylactic agents against antibiotic-associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients. Harefuah 2007;146:520–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jirapinyo P, Densupsoontorn N, Thamonsiri N, et al. Prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in infants by probiotics. J Med Assoc Thai 2002;85: Suppl 2: S739–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Friedman G. The role of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2012;41:763–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pérez C. Probiotics for the treating acute diarrhea and preventing antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children. Nutr Hosp 2015;31: Suppl 1: 64–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Szajewska H, Canani RB, Guarino A, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;62:495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ye Q, Liu Q. Clinical efficacy of Bacillus subtilis combined live bacteria granules in treating children with diarrhea. China Continuing Medical Education 2016;8:194–5. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Haire Guli B. Study on the clinical effect of treating infantile diarrhea with Bacillus subtilis combined living bacteria granules. Journal of Contemporary Medicine 2015;13:280–1. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Si YL. Study on the clinical effect of oral treatment of children's diarrhea with Bacillus subtilis combined live particles. Modern Doctor of China 2015;53:54–6. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ye WW. Clinical efficacy analysis of Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus multi-active granules combined with montmorillonite powder in the treatment of children with antibiotic-related diarrhea, Journal of Practical Heart, Brain. Pulmonary and Vascular Diseases 2013;21:119–20. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Qu ZH. Clinical efficacy of Bacillus subtilis combined live bacteria granules in treating children with diarrhea. Contemporary Medicine 2012;18:116–7. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shen FY. Clinical observation on the treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children with Bacillus subtilis combined live particles. Medical Information 2010;23:1896. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gorenek L, Dizer U, Besirbellioglu B, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of Clostridium difficile in antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Hepatogastroenterology 1999;46:343–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chen S, Fu Y, Liu LL, et al. Live combined Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium Ameliorate Murine experimental Colitis by immunosuppression. Int J Inflam 2014;2014:878054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wu QF. Live combined Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium enteric-coated capsules in treating 60 children with functional abdominal pain. Asian Case Reports in Pediatrics 2013;1:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zusman M. The absolute visual analogue scale (AVAS) as a measure of pain intensity. Aust J Physiother 1986;32:244–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Breivik H. Fifty years on the visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain-intensity is still good for acute pain. But multidimensional assessment is needed for chronic pain. Scand J Pain 2016;11:150–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Vriesman MH, Velasco-Benitez CA, Ramirez CR, et al. Assessing children's report of stool consistency: agreement between the pediatric Rome III questionnaire and the Bristol stool scale. J Pediatr 2017;190:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Caroff DA, Edelstein PH, Hamilton K, et al. The Bristol stool scale and its relationship to Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Microbiol 2014;52:3437–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]