Abstract

In the kinase field, there are many widely held tenants about conformation-selective inhibitors that have yet to be validated using controlled experiments. We have designed, synthesized, and characterized a series of kinase inhibitor analogs of dasatinib, an FDA-approved kinase inhibitor that binds the active conformation. This inhibitor series includes two Type II inhibitors that bind the DFG-out inactive conformation and two inhibitors that bind the αC-helix out inactive conformation. Using this series of compounds, we analyze the impact that conformation-selective inhibitors have on target binding and kinome-wide selectivity.

INTRODUCTION

Protein kinases (PKs) play a key role in cellular signal transduction pathways and regulate important cellular processes such as cell growth through post-translational phosphorylation. PKs are one of the largest protein families; the human kinome encodes for 518 protein kinases, which corresponds to 1.7% of the entire genome.1 For these reasons, they continue to be an attractive target for drug discovery.

Structural analysis of the FDA-approved kinase inhibitors reveals three distinct kinase conformations amenable to inhibitor binding: DFG-in active, DFG-out inactive, and αC-helix out inactive.2–5 The majority of approved kinase inhibitors (19 of 30) bind the active kinase conformation and these inhibitors have previously been classified as ‘Type I’ inhibitors. There are 7 approved kinase inhibitors that bind the inactive, DFG-out conformation and these inhibitors have been termed ‘Type II’ inhibitors. Finally, 4 approved inhibitors bind an alternate inactive conformation, the αC-helix out conformation.

Type I inhibitors are the most common kinase inhibitor class, both among approved and non-approved inhibitors. These inhibitors bind their target kinase(s) in a manner similar to ATP, where the kinase is in an active conformation (in which the activation loop is poised for phosphate transfer).6 Meanwhile, Type II inhibitors bind an inactive kinase conformation in which the activation loop is forced to undergo a large conformational change due to the kinase inhibitor occupying an allosteric pocket adjacent to the nucleotide-binding site.7 The specific inactive conformation bound by Type II inhibitors is termed the DFG-out inactive conformation. In this conformation, the conserved Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG) motif required for catalysis is flipped outward so that the Asp faces into the solvent and can no longer coordinate ATP/Mg2+. Finally, αC-helix out inhibitors stabilize the kinase in a conformation where a key salt bridge between the catalytic lysine and a glutamate in helix αC is disrupted due to displacement (and/or outward rotation) of the αC-helix.8–12

Because the kinase ATP pocket is highly conserved, developing selective kinase inhibitors remains a key challenge for the drug discovery and chemical biology fields. Since the discovery of imatinib,13,14 a selective Type II inhibitor of c-Abl, the prevailing opinion has been that Type II inhibitors are more selective than their Type I counterparts.15,16 It is commonly believed that not all kinases can adopt the DFG-out conformation.17–19 These beliefs originate in the finding that imatinib does not inhibit c-Src, a protein kinase with homology to c-Abl.20,21 The prevailing hypothesis was that imatinib did not bind c-Src, because c-Src cannot adopt the DFG-out conformation.22 However, it was later shown that c-Src can in fact readily adopt the DFG-out conformation.23–26 Kinome-wide analyses of kinase inhibitors initially strengthened the idea that Type II inhibitors were more selective,27 however, recent analyses suggest that the DFG-out conformation is conserved across the kinome.7,28 Nonetheless, Type II inhibitors are still today claimed to be more selective than Type I kinase inhibitors.29 No comprehensive selectivity analysis of inhibitors that bind the αC-helix out (CHO) conformation has been performed, however, three of the FDA-approved inhibitors that bind this specific inactive conformation (lapatinib, vemurafenib, and ibrutinib) are among the most selective kinase inhibitors known.27,30,31 Complicating matters, CHO inhibitors are often incorrectly considered Type I inhibitors in analyses of kinome profiling data.7,18,32

In an effort to understand the role of conformation on the selectivity of kinase inhibitors, we have created a set of conformation-selective analogs of dasatinib, an FDA-approved pan-kinase inhibitor.4 Dasatinib is a potent inhibitor of c-Src (along with many other tyrosine kinases) and binds the active kinase conformation.33,34 Herein, we designed analogs of dasatinib that bind the DFG-out and αC-helix out conformations of c-Src. Crystallographic characterization of our conformation-selective dasatinib analogs confirms the desired inactive conformations. Selectivity profiling across a diverse kinome panel yields insight into the divergent selectivity of conformation-selective inhibitors. Notably, these inhibitors represent the first ‘matched set’ of conformation-selective kinase inhibitors that share the same hinge-binding scaffold and have been verified crystallographically. Using this unique inhibitor set, our results provide a deeper understanding of kinase inhibitor structure–function and selectivity.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design and structural characterization of DFG-out dasatinib analogs.

To design an analog of dasatinib that invokes the DFG-out conformation, we applied a hybridization strategy developed by Gray and colleagues for converting Type I kinase inhibitors into Type II inhibitors.32,35 Specifically, we created an overlay of dasatinib bound to c-Src (PDB: 3G5D) with imatinib bound to c-Src (PDB: 2OIQ) (Figure 1A). The overlaid structures suggested that addition of a benzamide group to the meta-position of dasatinib’s distal phenyl could result in a potent Type II analog of dasatinib. Following this design strategy, we synthesized two putative Type II inhibitors: DAS-DFGO-I and DAS-DFGO-II. These compounds vary only in the inclusion of a so-called ‘flag methyl’, a methyl group found both in dasatinib and in many Type II kinase inhibitors,7 including imatinib.

Figure 1.

(A) Overlay of dasatinib (blue) and imatinib (red) kinase inhibitors used in the design of dasatinib DFG-out analogs, DAS-DFGO-I and DAS-DFGO-II. (B) DAS-DFGO-I (white) bound to c-Src (PDB: 4YBJ). P-loop (blue), αC-helix (yellow) and DFG motif (red) are shown. (C) The trifluoromethyl benzamide group is positioned within the DFG pocket, resulting in the DFG-out, inactive kinase conformation.

Dasatinib is a highly potent inhibitor of both c-Src and c-Abl (Ki < 1 nM). In activity assays, both DAS-DFGO-I and DAS-DFGO-II titrated the lowest enzyme concentration that can be used in this assay (Ki < 1 nM for both Type II analogs; Supplemental Figure S1). To confirm that these Type II analogs invoke the DFG-out conformation, we obtained a crystal structure of DAS-DFGO-I bound to c-Src kinase domain (PDB: 4YBJ, Figure 1B). Several dasatinib:c-Src interactions were conserved in this crystal structure, including hydrogen bond contacts to the hinge and gatekeeper residues of c-Src (Figure 1C). Gratifyingly, c-Src is in the DFG-out inactive conformation when bound to DAS-DGFO-I, highlighted by the outward flip of Phe-405. The benzamide group we appended to dasatinib occupies the DFG-pocket, with the amide hydrogen bonding to Glu-310 and Asp-404, all of which are prototypical features of Type II inhibitors. Notably, a previously obtained crystal structure of imatinib bound to c-Src illustrates an identical, DFG-out binding mode (Supplemental Figure S2).

Design and structural characterization of αC-helix-out dasatinib analogs.

While design strategies for the conversion of Type I kinase inhibitors into Type II inhibitors are known,32,35 no such strategy has been proposed for the conversion of Type I inhibitors into αC-helix out (CHO) binding analogs. Thus, we first analyzed the binding space occupied by existing CHO inhibitors that have co-crystal structures available (for a list of CHO inhibitors used, see Supplemental Table S1).36 In contrast to Type II inhibitors, CHO inhibitors typically contain a bulky substituent that extends directly toward the αC-helix and lack hydrogen bond donors typically found in Type II inhibitors. Indeed, phenoxy or benzyloxy groups are commonly employed in the design of CHO inhibitors.12,37,38 An overlay of dasatinib:c-Src (PDB: 3G5D) with a panel of known and verified CHO inhibitors (Figure 2A), suggested that addition of a para-phenoxy group to dasatinib could lead to an optimal CHO analog of dasatinib. Thus, we synthesized two putative CHO inhibitors: DAS-CHO-I and DAS-CHO-II, where DAS-CHO-II incorporates the ‘flag methyl’ found in dasatinib and DAS-DFGO-II.

Figure 2.

(A) Overlay of dasatinib (blue) with the binding space (yellow) of structurally confirmed CHO inhibitors. A para-phenoxy group addition to dasatinib led to the generation of DAS-CHO-I and DAS-CHO-II. (B) DAS-CHO-I bound to c-Src (PDB: 4YBK). (C) An overlay with dasatinib bound to c-Src (PDB: 3G5D) shows the magnitude of the αC-helix shift (~5 Å) and incompatible binding between the CHO inhibitor and the Glu310 side chain of the kinase. (D) DAS-CHO-I bound to c-Abl (PDB: 4YC8). (E) The possible range of αC-helix positioning, from αC-helix in (blue) to c-Abl αC-helix out (green) to c-Src αC-helix out (yellow).

Consistent with dasatinib and the DFG-out analogs of dasatinib, both DAS-CHO-I and DAS-CHO-II are exceptionally potent in biochemical activity assays against both c-Src and c-Abl (Supplemental Figure S3). To confirm the proposed CHO conformation, we obtained a crystal structure of DAS-CHO-I bound to the c-Src kinase domain (Figure 2B; PDB: 4YBK). c-Src bound to DAS-CHO-I adopts the classic CHO (also termed Src/Cdk-like) inactive conformation8–12, as evidenced by the outward rotation of the αC-helix and outward projection of Glu-310 side chain from the ATP pocket. The phenoxy group cannot be accommodated within the DFG pocket and thus occupies the empty space that results from the outward movement of the αC-helix. As with the DFG-out analog, the hinge contacts are conserved and the Type I portion of the molecule bears striking similarity to dasatinib’s binding mode. In the c-Src:DAS-CHO-I structure the αC-helix is rotated nearly 5 Å from the active conformation of c-Src (Figure 2C), a change consistent with the binding of other CHO inhibitors to c-Src.11,12

Recent evidence has suggested that many kinases can adopt the DFG-out inactive conformation, however, relatively little is known about which kinases can adopt the CHO inactive conformation. Because our results showed that c-Abl was potently inhibited by DAS-CHO-I, we obtained a crystal structure of this CHO inhibitor bound to c-Abl (Figure 2D). In this structure, there is less movement of the αC-helix (Figure 2E), however, the key lysine-glutamate salt bridge is disrupted, which is a unique feature of CHO inhibitors. A recently reported structure of a CHO inhibitor bound to Erk2 possesses the same features (minimal movement of αC-helix and disruption of Lys-Glu salt bridge).38 Notably, our structure is the first of c-Abl bound to a small molecule inhibitor that binds the CHO inactive conformation.39

Characterization of conformation-selective dasatinib analogs binding to target kinases.

Due to the constraints of our activity-based assays for c-Src and c-Abl (the main targets of dasatinib), we used the KINOMEscan service40 to obtain quantitative Kd values for both c-Src and c-Abl (Table 1). Each compound is a very potent inhibitor of both c-Src and c-Abl without discrimination between targets.

Table 1.

KINOMEscan Kd profiling of conformation-selective dasatinib analogs.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | binding mode | R2 | c-Src Kd, nM | c-Abl Kd, nM |

| Dasatinib | active | Me | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| DAS-DFGO-I | DFG-out | H | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 2.2 ± 0.3 |

| DAS-DFGO-II | DFG-out | Me | 2.7 ± 0.01 | 2.9 ± 0.05 |

| DAS-CHO-I | CHO | H | 15 ± 3 | 14 ± 1 |

| DAS-CHO-II | CHO | Me | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.32 ± 0.02 |

We also examined the ability of our probes to bind to c-Abl that has been phosphorylated on the activation loop. Largely on the basis of imatinib’s strong preference for non-phosphorylated c-Abl,21,41,42 an often reported “feature” of Type II inhibitors is that they bind c-Abl tighter than c-Abl~pY393.26,35,43 Given this frequently claimed feature, we were surprised to see that both DAS-DFGO-I and DAS-DFGO-II have no preference between the activation state of the kinase (Table 2). To follow up on these results, we screened a panel of bona fide Type II inhibitors of c-Abl (imatinib, nilotinib, rebastinib, and ponatinib) for which a crystal structure verifies the DFG-out inactive conformation,41,44–46 and found that only imatinib has a preference for c-Abl over c-Abl-pY393. Imatinib’s hydrophobic hinge binding functionality has been hypothesized to be responsible for its preference for non-phosphorylated c-Abl.24,26 From these studies, we can state that Type II kinase inhibitors do not have an inherent activation-state preference in biochemical assays and this type of measurement cannot be relied upon to determine inhibitor binding mode, despite claims to the contrary.35,43

Table 2.

Type II inhibitor phosphorylation state dependence comparison

| Inhibitor | c-Abl Kd, nM | c-Abl~pY393 Kd, nM |

|---|---|---|

| DAS-DFGO-I | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| DAS-DFGO-II | 2.9 ± 0.05 | 2.0 ± 0.01 |

| imatinib | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 24 ± 1 |

| nilotinib | 11 ± 2 | 15 ± 4 |

| rebastinib | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 11 ± 5 |

| Ponatinib | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

In general, Type II inhibitors have been reported to have longer residence times, compared to Type I kinase inhibitors.21,24,47–49 However, these studies have not been performed using a controlled set of inhibitors, such as our dasatinib analogs. Thus, we synthesized BODIPY-labeled analogs (Figure 3A) for four of our dasatinib analogs (DAS-, DAS-DFGO-I-, DAS-DFGO-II, and DAS-CHO-II-BODIPY; for all probe data with wt c-Src and c-Abl, see Supplemental Figure S4). We first obtained Kd values for each probe and verified that binding was not impacted by addition of BODIPY-FL on the solvent-exposed piperazine ring. We then determined off-rates for each probe with both c-Src and c-Abl kinase domains. Consistent with previous reports, our Type II probes have significantly longer half-lives compared to the active-binding analog with both c-Src and c-Abl (Figure 3B). Relatively little is known about the binding kinetics of CHO kinase inhibitors, however, lapatinib (an FDA-approved CHO kinase inhibitor), has an exceptionally long half-life with its primary target EGFR (t1/2 = 300 min).37 We found that DAS-BODIPY and DAS-CHO-II-BODIPY have nearly identical off-rates (Supplemental Figure S4) for both c-Src and c-Abl, suggesting that a slow off-rate is not an inherent feature of CHO kinase inhibitors.

Figure 3.

(A) DAS- and DAS-DFGO-II-BODIPY structures. (B) Determination of BODIPY probes half-life values. A significantly longer half-life measurement was observed for DAS-DFGO-II-BODIPY (red) in comparison to DAS-BODIPY (blue) (C) Kinetic and thermodynamic data comparison for type I and type II BODIPY probes.

A significant amount of effort has been spent on understanding the binding preference of imatinib for c-Abl over c-Src.21,50,51 Initial reports suggested that c-Src was unable to adopt the DFG-out conformation (a hypothesis that has since been clearly refuted).22 Despite evidence to the contrary,23–26 the belief that there is an energetic penalty for c-Src to invoke the DFG-out conformation persists.52–54 Our probes represent a unique opportunity to examine whether there is any penalty (kinetic or thermodynamic) for the DFG-out conformation in c-Src. Using DAS-BODIPY and DAS-DFGO-II-BODIPY, we compared the binding of each probes to both c-Src and c-Abl kinase domains. With DAS-BODIPY, we observed no significant change in kinetics (kon and koff) or thermodynamics (Kd) of binding (Figure 3C). Likewise, we observed no significant change in the kinetics and thermodynamics for binding of DAS-DFGO-II-BODIPY. We also observed no significant differences between c-Src kinase domain and full-length constructs. From these data, we conclude that imatinib’s preference for c-Abl over c-Src is inherent to the ligand structure of imatinib and not conserved between Type II inhibitors.24

To complement our thermodynamic data (Kd values, Table 2) that suggest Type II inhibitors do not have a preference for a specific kinase activation-state, we examined the kinetics of DAS-BODIPY and DAS-DFGO-II-BODIPY for binding to c-Src~pY416 (activation-loop phosphorylated c-Src kinase domain). We found no significant change in the binding of either inhibitor (Supplemental Figure S5). These data reinforce our findings that conformation-selective inhibitors do not have an inherent activation-state preference in biochemical assays.

Selectivity profiling of conformation-selective dasatinib analogs.

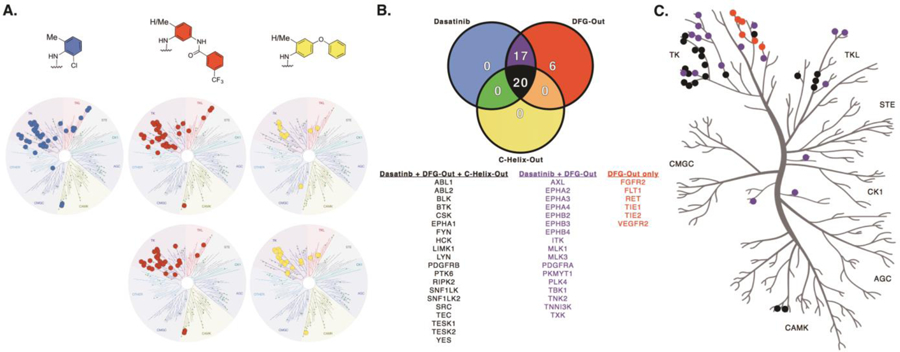

Type II inhibitors have been repeatedly stated to be more selective, in general, than Type I inhibitors.29 These analyses hinge upon the profiling of a collection of unrelated kinase inhibitors. Recent analyses have pointed out that several previously profiled Type II inhibitors are highly promiscuous,7 however, kinome-wide profiling of a matched set of conformation-selective kinase inhibitors has not been reported. Thus, we wanted to determine how the selectivity of dasatinib, a relatively promiscuous Type I inhibitor, compares to our panel of conformation-selective dasatinib analogs. We used a commercially available profiling service55,56 to profile each of the 5 analogs using a competition-binding assay for 124 non-mutant kinase domain constructs (Figure 4A; for individual kinase data, see Supplemental Data). We selected 500 nM as the screening concentration for each analog, a concentration that is significantly higher than each analog’s binding affinity for c-Src and c-Abl, the primary targets of dasatinib. Kinome-wide selectivity differences between the 5 compounds can be compared using their S-score. S-score represents the fraction of kinases inhibited to a particular level (e.g., S35 is the number of kinases with <35% of control activity divided by the total number of nonmutant kinases in the panel, here 124). In this panel, dasatinib has S35 = 0.21 at 500 nM. The Type II analogs (DAS-DFGO-I and DAS-DFGO-II) have similar S35 scores (0.24 and 0.20, respectively). Meanwhile, the CHO analogs are significantly more selective (DAS-CHO-I S35 = 0.05, DAS-CHO-II S35 = 0.16). It is worth noting that these selectivity scores do not correlate to inhibitor potency for an individual target (e.g., DAS-CHO-I, (S35 = 0.05) binds LIMK1 more potently than dasatinib (S35 = 0.21), see Supplemental Data for details).

Figure 4.

(A) Kinase target comparison for conformation-selective dasatinib analogs utilizing a 50% cutoff value. (B) Analysis of kinase targets amongst the three conformation-selective modes of inhibition. Twenty kinases are targeted equally by the inhibitor set, while six kinases demonstrate a preference for DFG-out binding. Seventeen kinases show shared inhibition between dasatinib and the two DFG-out inhibitors. (C) Kinome tree representation of kinase targets. Colors correspond to the Venn diagram.

This is the first kinome-wide selectivity analysis for a matched set of conformation-selective kinase inhibitors. Our findings suggest that conversion of a Type I inhibitor into a Type II inhibitor leads to similar or even reduced selectivity. This is in stark contrast to the dogma that Type II inhibitors are inherently more selective than their Type I counterparts.29 Of interest, is that while dasatinib is a poor inhibitor of non-Thr gatekeeper kinases, the Type II inhibitors (DAS-DFGO-I and DAS-DFGO-II) can potently inhibit many non-Thr gatekeeper kinases (Figure 4B). We confirmed this with by obtaining Kd values using an orthogonal assay (KINOMEscan Kd determinations) and found that several non-Thr gatekeeper kinases can be preferentially inhibited by the DFG-out analogs (Supplemental Table S2). Notably, there are no kinases (in this panel) that bind dasatinib and do not also bind to the Type II analogs. Thus, the ability of the DFG-out analogs to bind kinases with non-Thr gatekeeper residues is responsible for the observed slight loss of selectivity compared to dasatinib. On the basis of the similar selectivity obtained for all Type I and Type II analogs, the hinge binder is primary determinant for selectivity with these analogs. This has two important implications: 1) These data are in agreement with recent analyses that proposed that the DFG-out conformation is conserved across the kinome,7 and 2) Kinome-wide selectivity analyses using inhibitor sets are likely driven by the selectivity of the hinge binder.

Interestingly, there have been recent publications claiming that the gatekeeper residue is a primary determinant for a kinase’s ability to bind a Type II inhibitor.57 Specifically, it has been proposed that non-Thr gatekeeper residues can prevent a kinase’s ability to bind a Type II inhibitor. Our data clearly demonstrates that kinases with non-Thr gatekeeper residues can be inhibited by Type II inhibitors. In fact, in our panels many such kinases (e.g., FLT1, RET, TIE2) are only inhibited by the Type II analogs (Figure 4).

We found that both of the dasatinib CHO analogs (DAS-CHO-I and DAS-CHO-II) are more selective than dasatinib. Several kinases are bound potently by both dasatinib and the CHO analogs (e.g., c-Src, c-Abl, LIMK1), however, there are many kinases that dasatinib potently binds to which the CHO analogs cannot bind (e.g., EPHB2, PDGFRA, and TXK) (Figure 4B; Supplemental Table S3). The inability of certain kinases, including the entire Ephrin family, to bind the CHO inhibitors is responsible for the increase in selectivity for the CHO analogs. We did not identify any kinases that can accommodate the CHO analog that do not also potently bind the Type I analog. These results are intriguing and suggest that invoking the CHO inactive conformation could be a useful method to improve inhibitor selectivity, provided that the target kinase can adopt this inactive conformation. Furthermore, it suggests that the CHO inactive conformation is less conserved across protein kinases than the DFG-out inactive conformation (in contrast to the DFG-out conformation which is conserved kinome-wide).

Since the FDA-approval of imatinib in 2001, extensive effort has focused on the development of kinase inhibitors that target the inactive conformation(s) of kinases. On the basis of imatinib’s binding properties, many (incorrect) theories about kinase inhibitor were established, many of which are still widely believed.29 In an effort to evaluate how kinase inhibitor binding mode impacts selectivity, and target binding, we designed and characterized the first set of kinase inhibitor analogs that bind the active and inactive conformations (DFG-out and αC-helix out).

We have demonstrated that conversion of dasatinib to a Type II analog can decrease kinome-wide selectivity. The diminished selectivity observed with the Type II binding mode is a result of these analogs potently inhibiting non-Thr gatekeeper kinases (in contrast to the Type I analog). We also demonstrate that Type II inhibitors do not inherently prefer to bind the un-activated kinase state in biochemical assays. Our series of inhibitors represent the first set of kinase inhibitors that bind the active, DFG-out inactive, and αC-helix out conformations and represent a useful compound series to interrogate how kinase conformation impacts inhibitor binding and selectivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inhibitors

Dasatinib was purchased from LC Labs. DAS-DFGO-I, DAS-DFGO-II, DAS-CHO-I, DAS-CHO-II, DAS-BODIPY,58 DAS-DFGO-I-BODIPY, DAS-DFGO-II-BODIPY and DAS-CHO-II-BODIPY were synthesized as described in the Supplemental Data and prepared as 10 mM DMSO stock solutions

Protein Purification and Crystallization Conditions

Wild type chicken c-Src kinase domain (residues 251–533) and human c-Abl kinase domain (residues 229–512) in pET28a, modified with a TEV protease cleavable N-terminal 6x-His tag were provided by M. Seeliger (SUNY, Stony Brook) and J. Kuriyan (UC Berkeley). Cell growth and expression and protein purification were performed using modified literature protocols for expression of wild-type c-Src and c-Abl kinase domain.59 Briefly, the plasmid containing the kinase (pET28a) was transformed into E. Coli BL21DE3 cells already containing YopH phosphatase (pCDFDuet-1 plasmid) and plated on LB agar with kanamycin (50 µg/mL, kan) and streptomycin (50 µg/mL, SM) and grown overnight at 37 °C. A single colony was picked for a starter culture (LB containing kan/SM) and subsequently grown overnight at 37 °C. The next day, scaled up cultures (TB containing kan/SM) were grown to an OD600nm of 1.2 at 37 °C and cooled to 18 °C with shaking prior to induction for 16 h at 18 °C with 0.2 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested by 20 min centrifugation at 4,000 rpm at 4 °C and resuspended in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 25 mM imidazole (buffer A) supplemented with 0.1 mM PMSF for immobilized Ni metal affinity chromatography. Cells were lysed via sonication and insoluble protein and cell debris was sedimented through a 50-min centrifugation at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C. The clear supernatant was loaded onto the Ni-NTA agarose affinity column (batch, QIAGEN) column. The resin was washed with 50 column volumes of buffer A and five column volumes (3X) of buffer QB (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 1 M NaCl). Protein was eluted with five column volumes (4X) of buffer B (buffer A plus 0.5 M imidazole). The buffer B fractions were pooled together and cleaved with 0.1 mg of TEV per 2.5 mg of crude kinase. Cleaved protein was loaded onto an anion exchange column (Q Sepharose, Fast Flow, GE Healthcare Life sciences) equilibrated with buffer QA (buffer QB without 1 M NaCl). Proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0–35% buffer QB and peak fractions were combined (based on kinase activity assay) and concentrated down in order to be loaded onto a size-exclusion column (HiLoad Superdex S75, GE Healthcare Life sciences) equilibrated with buffer D (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT). Pure fractions via SDS-PAGE were combined and concentrated down to a concentration of ~8 mg/mL (~260 µM).

Kinase-inhibitor complexes were formed in solutions of 163 μM kinase domain, 250 μM inhibitor, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) DMSO and 5–6% (v/v) glycerol. Crystals grew overnight at 20 °C using hanging-drop vapor diffusion. Drops contained 1 μL of complex + 1 μL well solution (0.1 M MES (pH 6.5), 16–22% (w/v) PEG 3350 and 100–420 mM sodium acetate). Prior to data collection, crystals were cryoprotected in well solution plus 20% (v/v) glycerol. X-ray diffraction data for both c-Src complexes were collected at 100 K and at a wavelength of 0.9787 Å at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratories on the 21-ID-F beamline. Data for the c-Abl complex was collected at 100 K and at a wavelength of 0.9793 Å on the 21-ID-D beamline.

Structure Determination of Kinase-Inhibitor Complexes

For the three protein-inhibitor complexes, diffraction data were processed and scaled with HKL2000.60 The structures were solved by molecular replacement using PHASER.61 The inactive conformation of the kinase domain of chicken c-Src (PDB code 2OIQ21; residues 260–520 and PDB code 4DGG12; residues 266–519) without the αC-helix (residues 298–310) and the activation loop (residues 400–425) were the search models for the Src–DAS-DFGO-I and Src–DAS-CHO-I structures, respectively. The inactive conformation of the kinase domain of human c-Abl (PDB code 2G1T39; residues 232–502) without the αC-helix (residues 275–287) and the activation loop (residues 377–402) was the search model for the Abl–DAS-CHO-I complex. The structures were built with iterative rounds of electron density fitting in Coot62 and refinement in autoBUSTER.63 After the initial refinement, clear Fo-Fc density was visible for each compound in the ATP pocket of the protein. Three-dimensional coordinates and restraint files for each ligand were generated using smiles string in GRADE64 employing the mogul+qm option. The structures were analyzed with Molprobity65 and EDS server.66 Results are listed in Supplemental Data.

BODIPY Proble Kd Determination

An endpoint fluorescence assay49 was used to determine Kd values. Reaction volumes of 50 µL were used in 96-well plates. 34 µL of buffer A 1X (100 mM Tris pH 8, 10 mM MgCl2) was added to a single row, followed by 15 µL of enzyme (3.3X concentration) in buffer A with 3-fold dilutions (typically 125 nM, 42, 14, 4.6, 1.5, 0.5, 0.17, 0.06, 0.02, 0.01 and 0 µM final well concentration in buffer A). Then 1 µL of a 500 nM stock of the appropriate dasatinib analog BODIPY probe in DMSO was added (2% DMSO final). Wells were incubated at rt for 30 minutes prior to end point read (ex/em 485/535 nm). Reactions had final concentrations of 10 nM BODIPY-probe, 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 8) and 10 mM MgCl2. For Kd determination, the values were obtained directly from the nonlinear regression one-site binding curves (using normalized data) in the presence of various concentrations of the enzyme. The equation Y = (Bmax * X)/(Kd + X); was used in the nonlinear regression. All 4 runs were averaged together for each reported value.

Inhibitor Off-rate Determination

A multiple time point read fluorescence assay49 was used to determine dasatinib analog BODIPY off-rates. Briefly, 60 µL of total volume with 700 nM enzyme and 500 nM probe in buffer A 1X (Master Mix) was incubated at rt for 4 h along with 60 µL of 500 nM probe alone in buffer A 1X (Blank Mix). Following this incubation period, 4 µL of the master mix was added into 5 wells and 4 µL of the blank mix was added into 2 wells via multichannel pipette into 116 µL of buffer A 1X containing 5 µM (final concentration) unlabeled dasatinib (120 µL total, 30-fold dilution). Additionally, 4 µL of master mix was added into a single well of 116 µL of buffer A 1X containing 100 nM (final concentration) probe to maintain consistent plate reader gain values over the course of the fluorescent reads. Master mix dilutions with competitor had final concentrations of 23 nM enzyme, 17 nM BODIPY-probe, 5 µM unlabeled dasatinib, 100 mM Tris buffer pH 8 and 10 mM MgCl2. Reads (ex/em 485/535 nm) were taken every 10 minutes for the first 2 h, then every 20 min for next two hours and finally every 30 min for the remainder of the assay (12 h total). The values for koff determination were obtained directly from the nonlinear regression fits for one-phase decay curves (using blanked data). The equation Y = (Y0 − Plateau)*exp(−K*X) + Plateau; was used in the nonlinear regression. An average of 5 wells at each time point was utilized for the final fit values produced.

Kinome-wide Inhibitor Profiling

Inhibitor selectivity profiles were obtained through Luceome Biotechnologies (Tuscon, AZ). Each inhibitor was screened at 0.5 µM against a panel of 124 wt kinases.55,56

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank J. Kuriyan (UC Berkeley) for providing c-Src and c-Abl expression plasmids. We thank Daniel Trieber and Jeremy Hunt (DiscoverX, San Diego, CA) for assistance with KinomeScan Kd assays using phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated c-Abl constructs. The University of Michigan College of Pharmacy and the Kathy Bruk Pearce Research Fund of the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center financially supported this research. A National Institutes of Health Chemistry-Biology Interface Training Grant (GM008597) supported, in part, F.E.K. A National Institutes of Health Cellular Biotechnology Training Grant (GM008353) supported, in part, T.K.J. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02–06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817).

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

Crystallographic coordinates for the DAS-DFGO-I:c-Src, DAS-CHO-I:c-Src and DAS-CHO-I:c-Abl complexes have been deposited at the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 4YBJ, 4YBK, 4YC8 (respectively).

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Data include five figures and three tables and can be found with this article online.

REFERENCES

- (1).Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, and Sudarsanam S (2002) The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 298, 1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research. (2015) USFDA approved protein kinase inhibitors compiled by Robert Roskoski Jr http://www.Brimr.Org/PKI/PKIs.htm

- (3).Breen ME, Steffey ME, Lachacz EJ, Kwarcinski FE, Fox CC, and Soellner MB (2014) Substrate activity screening with kinases: discovery of small-molecule substrate-competitive c-Src inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 53, 7010–7013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wang Q, Zorn JA, and Kuriyan J Chapter Two. (2014) A structural atlas of kinases inhibited by clinically approved drugs. Methods In Enzymology 548, 23–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wu P, Nielsen TE, and Clausen MH (2015) FDA-approved small-molecule kinase inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 36, 422–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Zhang J, Yang PL, and Gray NS (2009) Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 28–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zhao Z, Wang L, Liu Y, Knapp S, Liu Q, and Gray NS (2014) Exploration of type II binding mode: a privileged approach for kinase inhibition focused drug discovery? ACS Chem. Biol 9, 1230–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sicheri F, Moarefi I, and Kuriyan J (1997) Crystal structure of the Src family tyrosine kinase Hck. Nature 385, 602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Xu W, Harrison SC, and Eck MJ (1997) Three-dimensional structure of the tyrosine kinase c-Src. Nature 385, 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jura N, Zhang X, Endres NF, Seeliger MA, Schindler T, and Kuriyan J (2011) Catalytic control in the EGF receptor and its connection to general kinase regulatory mechanisms. Mol. Cell 42, 9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Georghiou G, Kleiner RE, Pulkoski-Gross M, Liu DR, and Seeliger MA (2012) Highly specific, bisubstrate-competitive Src inhibitors from DNA-templated macrocycles. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 366–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Krishnamurty R, Brigham JL, Leonard SE, Ranjitkar P, Larson ET, Dale EJ, Merritt EA, and Maly DJ (2013) Active site profiling reveals coupling between domains in SRC-family kinases. Nat. Chem. Biol 9, 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Capdeville R, Buchdunger E, Zimmermann J, and Matter A Glivec (STI571, imatinib), a rationally developed, targeted anticancer drug. (2002) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 1, 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Sawyers CL (2002) Disabling Abl-perspectives on Abl kinase regulation and cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell 1, 13–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Mol CD, Fabbro D, and Hosfield DJ (2004) Structural insights into the conformational selectivity of STI-571 and related kinase inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel 7, 639–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Backes AC, Zech B, Felber B, Klebl B, and Müller G (2008) Small-molecule inhibitors binding to protein kinase. Part II: the novel pharmacophore approach of type II and type III inhibition. Expert Opin. Drug Discov 3, 1427–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Morphy R (2010) Selectively nonselective kinase inhibition: striking the right balance J. Med. Chem 53, 1413–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zuccotto F, Ardini E, Casale E, and Angiolini M (2010) Through the “gatekeeper door”: exploiting the active kinase conformation. J. Med. Chem 53, 2681–2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Hari SB, Merritt EA, and Maly DJ (2013) Sequence determinants of a specific inactive protein kinase conformation. Chem. Biol 20, 806–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Deininger M, Buchdunger E, and Druker BJ (2005) The development of imatinib as a therapeutic agent for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 105, 2640–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Seeliger MA, Nagar B, Frank F, Cao X, Henderson MN, and Kuriyan J (2007) c-Src binds to the cancer drug imatinib with an inactive Abl/c-Kit conformation and a distributed thermodynamic penalty. Structure 15, 299–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Cowan-Jacob SW, Fendrich G, Manley PW, Jahnke W, Fabbro D, Liebetanz J, and Meyer T (2005) The crystal structure of a c-Src complex in an active conformation suggests possible steps in c-Src activation. Structure 13, 861–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Dar AC, Lopez MS, and Shokat KM (2008) Small molecule recognition of c-Src via the Imatinib-binding conformation. Chem. Biol 15, 1015–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Seeliger MA, Ranjitkar P, Kasap C, Shan Y, Shaw DE, Shah NP, Kuriyan J, and Maly DJ (2009) Equally potent inhibition of c-Src and Abl by compounds that recognize inactive kinase conformations. Cancer Research 69, 2384–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Simard JR, Klüter S, Grütter C, Getlik M, Rabiller M, Rode HB, and Rauh D (2009) A new screening assay for allosteric inhibitors of cSrc. Nat. Chem. Biol 5, 394–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hari SB, Perera BGK, Ranjitkar P, Seeliger MA, and Maly DJ (2013) Conformation-selective inhibitors reveal differences in the activation and phosphate-binding loops of the tyrosine kinases Abl and Src. ACS Chem. Biol 8, 2734–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Davis MI, Hunt JP, Herrgard S, Ciceri P, Wodicka LM, Pallares G, Hocker M, Treiber DK, and Zarrinkar PP (2011) Comprehensive analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat. Biotechnol 29, 1046–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Namboodiri HV, Bukhtiyarova M, Ramcharan J, Karpusas M, Lee Y, and Springman EB (2010) Analysis of imatinib and sorafenib binding to p38alpha compared with c-Abl and b-Raf provides structural insights for understanding the selectivity of inhibitors targeting the DFG-out form of protein kinases. Biochemistry 49, 3611–3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Fabbro D, Cowan-Jacob SW, and Moebitz H (2015) Ten things you should know about protein kinases: IUPHAR Review 14. Brit. J. Pharmacol 172, 2675–2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Pan Z, Scheerens H, Li SJ, Schultz BE, Sprengeler PA, Burrill LC, Mendonca RV, Sweeney MD, Scott KC, Grothaus PG, Jeffery DA, Spoerke JM, Honigberg LA, Young PR, Dalrymple SA, and Palmer JT (2007) Discovery of selective irreversible inhibitors for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. ChemMedChem 2, 58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Bollag G, Tsai J, Zhang J, Zhang C, Ibrahim P, Nolop K, and Hirth P (2012) Vemurafenib: The first drug approved for BRAF-mutant cancer. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 11, 873–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Liu Y and Gray NS (2006) Rational design of inhibitors that bind to inactive kinase conformations. Nat. Chem. Biol 2, 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lombardo LJ, Lee FY, Chen P, Norris D, Barrish JC, Behnia K, Castaneda S, Cornelius LA, Das J, Doweyko AM, Farichild C, Hunt JT, Inigo I, Johnston K, Kamath A, Kan D, Klei H, Marathe P, Pang S, Peterson R, Pitt S, Schieven GL, Schmidt RJ, Tokarski J, Wen ML, Wityak J, and Borzilleri RM (2004) Discovery of N-(2-chloro-6-methyl-phenyl)-2-(6-(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)- piperazin-1-yl)-2-methylpyrimidin-4-ylamino)thiazole-5-carboxamide (BMS-354825), a dual Src/Abl kinase inhibitor with potent antitumor activity in preclinical assays. J. Med. Chem 47, 6658–6661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Tokarski JS, Newitt JA, Chang CY, Cheng JD, Wittekind M, Kiefer SE, Kish K, Lee FY, Borzillerri R, Lombardo LJ, Xie D, Zhang Y, and Klei HE (2006) The structure of dasatinib (BMS-354825) bound to activated ABL kinase domain elucidates its inhibitory activity against imatinib-resistant ABL mutants. Cancer Res 66, 5790–5797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Okram B, Nagle A, Adrián FJ, Lee C, Ren P, Wang X, Sim T, Xie Y, Wang X, Xia G, Spraggon G, Warmuth M, Liu Y, and Gray NS (2006) A general strategy for creating ‘‘inactive-conformation’’ Abl inhibitors. Chem. Biol 13, 779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).van Linden OPJ, Kooistra AJ, Leurs R, de Esch IJP, and de Graaf C (2014) KLIFS: a knowledge-based structural database to navigate kinase-ligand interaction space. J. Med. Chem 57, 249–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wood ER, Truesdale AT, McDonald OB, Yuan D, Hassell A, Dickerson SH, Ellis B, Pennisi C, Horne E, Lackey K, Alligood KJ, Rusnak DW, Gilmer TM, and Shewchuk L (2004) A unique structure for epidermal growth factor receptor bound to GW572016 (Lapatinib): Relationships among protein conformation, inhibitor off-rate, and receptor activity in tumor cells. Cancer Research 64, 6652–6659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hari SB, Merritt EA, and Maly DJ (2014) Conformation-selective ATP-competitive inhibitors control regulatory interactions and noncatalytic functions of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Chem. Biol 21, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Levinson NM, Kuchment O, Shen K, Young MA, Koldobskiy M, Karplus M, Cole PA, and Kuriyan J (2006) A Src-like inactive conformation in the Abl tyrosine kinase domain. PLOS Biology 4, 753–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Fabian MA, Biggs WH, Treiber DK, Atteridge CE, Azimioara MD, Benedetti MG, Carter TA, Ciceri P, Edeen PT, Floyd M, Ford JM, Galvin M, Gerlach JL, Grotzfeld RM, Herrgard S, Insko DE, Insko MA, Lai AG, Lelias J-M, Mehta SA, Milanov ZV, Velasco AM, Wodicka LM, Patel HK, Zarrinkar PP, and Lockhart DJ (2005) A small-molecule-kinase interaction map for clinical kinase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol 23, 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Schindler T, Bornmann W, Pellicena P, Miller WT, Clarkson B, and Kuriyan J (2000) Structural mechanism for STI-571 inhibition of abelson tyrosine kinase. Science 289, 1938–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Nagar B, Bornmann WG, Pellicena P, Schindler T, Veach DR, Miller WT, Clarkson B, and Kuriyan J (2002) Crystal structures of the kinase domain of c-Abl in complex with the small molecule inhibitors PD173955 and imatinib (STI-571). Cancer Res 62, 4236–4243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Wodicka LM, Ciceri P, Davis MI, Hunt JP, Floyd M, Salerno S, Hua XH, Ford JM, Armstrong RC, Zarrinkar PP, and Treiber DK (2010) Activation state-dependent binding of small molecule kinase inhibitors: structural insights from biochemistry. Chem. Biol 17, 1241–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Weisberg E, Manley PW, Breitenstein W, Bruggen J, Cowan-Jacob SW, Ray A, Huntly B, Fabbro D, Fendrich G, Hall-Meyers E, Kung AL, Mestan J, Daley GQ, Callahan L, Catley L, Cavazza C, Azam M, Neuberg D, Wright RD, Gilliland DG, and Griffin JD (2005) Characterization of AMN107, a selective inhibitor of native and mutant Bcr-Abl. Cancer Cell 7, 129–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, Eide CA, Rivera VM, Wang F, Adrian LT, Zhou T, Huang W, Xu Q, Metcalf CA III, Tyner JW, Loriaux MM, Corbin AS, Wardwell S, Ning Y, Keats JA, Wang Y, Sundaramoorthi R, Thomas M, Zhou D, Snodgrass J, Commodore L, Sawyer TK, Dalgarno DC, Deininger MWN, Druker BJ, and Clackson T (2009) AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell 16, 401–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Chan WW, Wise SC, Kaufman MD, Ahn YM, Ensinger CL, Haack T, Hood MM, Jones J, Lord JW, Lu WP, Miller D, Patt WC, Smith BD, Petillo PA, Rutkoski TJ, Telikepalli H, Vogeti L, Yao T, Chun L, Clark R, Evangelista P, Gavrilescu LC, Lazarides K, Zaleskas VM, Stewart LJ, Van Etten RA, and Flynn DL (2011) Conformational control inhibition of the BCRABL1 tyrosine kinase, including the gatekeeper T315I mutant, by the switch-control inhibitor DCC-2036. Cancer Cell 19, 556–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Pargellis C, Tong L, Churchill L, Cirillo PF, Gilmore T, Graham AG, Grob PM, Hickey ER, Moss N, Pav S, and Regan J (2002) Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase by utilizing a novel allosteric binding site. Nat. Struct. Biol 9, 268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Sullivan JE, Holdgate GA, Campbell D, Timms D, Gerhardt S, Breed J, Breeze AL, Bermingham A, Pauptit RA, Norman RA, Embrey KJ, Read J, VanScyoc WS, and Ward WHJ (2005) Prevention of MKK6-dependent activation by binding to p38α MAP kinase. Biochemistry 44, 16475–16490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Ranjitkar P, Brock AM, and Maly DJ (2010) Affinity reagents that target a specific inactive form of protein kinases. Chem. Biol 17, 195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Agafonov RV, Wilson C, Otten R, Buosi V, and Kern D (2014) Energetic dissection of Gleevec’s selectivity toward human tyrosine kinases. Nat. Mol. Struc. Biol 21, 848–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Wilson C, Agafonov RV, Hoemberger M, Kutter S, Zorba A, Halpin J, Buosi V, Otten R, Waterman D, Theobald DL, and Kern D (2015) Using ancient protein kinases to unravel a modern cancer drug’s mechanism. Science 347, 882–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Aleksandrov A and Simonson T (2010) Molecular dynamics simulations show that conformational selection governs the binding preferences of imatinib for several tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem 285, 13807–13815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Lovera S, Sutto L, Boubeva R, Scapozza L, Dölker N, and Gervasio FL (2012) The different flexibility of c-Src and c-Abl kinases regulates the accessibility of a druggable inactive conformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 2496–2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Lin Y-L, Meng Y, Jiang W, and Roux B (2013) Explaining why Gleevec is a specific and potent inhibitor of Abl kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 110, 1664–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Jester BW, Cox KJ, Gaj A, Shomin CD, Porter JD, and Ghosh I (2010) A coiled-coil enabled split-luciferase three-hybrid system: applied toward profiling inhibitors of protein kinases. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 11727–11735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Jester BW, Gaj A, Shomin CD, Cox KJ, and Ghosh I (2012) Testing the promiscuity of commercial kinase inhibitors against the AGC kinase group using a split-luciferase screen. J. Med. Chem 55, 1526–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Bosc N, Wroblowski B, Aci-Sèche S, Meyer C, and Bonnet P (2015) A proteometric analysis of human kinome: insight into discriminant conformation-dependent residues. ACS Chem. Biol. ASAP DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Vetter ML, Zhang Z, Shuai L, Wang J, Cho H, Zhang J, Zhang W, Gray NS, and Yang PL (2014) Fluorescent Visualization of Src by Using Dasatinib-BODIPY. ChemBioChem 15, 1317–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Seeliger MA, Young M, Henderson MN, Pellicena P, King DS, Falick AM, and Kuriyan J (2005) High yield bacterial expression of active c-Abl and c-Src tyrosine kinases. Protein Sci. 14, 3135–3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Otwinowski Z and Minor W (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, and Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Cryst 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Bricogne G, Blanc E, Brandl M, Flensburg C, Keller P, Paciorek W, Roversi P, Sharff A, Smart OS, Vonrhein C, and Womack TO (2011) Buster version 2.10.0 Ed, Global Phasing Ltd., Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Smart OS, Womack TO, Sharff A, Flensburg C, Keller P, Paciorek W, Vonrhein C, and Bricogne G (2011) GRADE version 1.1.1.

- (65).Chen VB, Arendall WB III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, and Richardson DC (2010). MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallographica D66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (66). Obtained from PDB validation report.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.