Abstract

Steeper rates of temporal discounting—the degree to which smaller-sooner (SS) rewards are preferred over larger-later (LL) ones—have been associated with impulsive and ill-advised behaviors in adolescence. Yet, the underlying neural systems remain poorly understood. Here we used a well-established temporal discounting paradigm and functional MRI (fMRI) to examine engagement of the striatum—including the caudate, putamen, and ventral striatum (VS)—in early adolescence (13–15 years; N=27). Analyses provided evidence of enhanced activity in the caudate and VS during impulsive choice. Exploratory analyses revealed that trait impulsivity was associated with heightened putamen activity during impulsive choices. A more nuanced pattern was evident in the cortex, with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex mirroring the putamen and posterior parietal cortex showing the reverse association. Taken together, these observations provide an important first glimpse at the distributed neural systems underlying economic choice and trait-like individual differences in impulsivity in the early years of adolescence, setting the stage for prospective-longitudinal and intervention research.

Introduction

Adolescents are more likely than adults to prefer immediate gratification over delayed rewards—a tendency that can result in behavioral choices with harmful long-term consequences, including drug and alcohol misuse and unsafe sex (Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008). Although these ill-advised behavioral tendencies are most often examined in older adolescents, there is growing evidence that early adolescents are also prone to short-sighted behavioral choices, including using nicotine (e.g. e-cigarettes) and drinking alcohol (Miech, Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Patrick, 2019; Rew, Horner, & Brown, 2011; Sikora, 2016). Adolescence is not a unitary period of development and it is unclear whether inferences drawn from studies of older adolescents apply to early adolescents. In particular, there is an urgent need to develop a deeper understanding of the neurocomputational processes underlying impulsive choices in early adolescence. Of these, temporal discounting—the degree to which real or hypothetical future rewards are devalued relative to those that are immediately available as a function of their delay in time—has been most intensely scrutinized (Bickel & Marsch, 2001; Green & Myerson, 2004; Hamilton, et al., 2015). Steeper rates of temporal discounting (i.e., a greater tendency to prefer smaller-sooner [SS] to larger-later [LL] rewards) have been associated with a broad spectrum of potentially harmful behaviors (e.g., substance use) in cross-sectional and prospective-longitudinal studies of adults and adolescents (Amlung, Vedelago, Acker, Balodis, & MacKillop, 2017; Lee, et al., 2014; Moody, Franck, Hatz, & Bickel, 2016). Among adults, neuroimaging studies have consistently implicated ventral and dorsal striatal and posterior parietal regions in temporal decision-making, with some studies also implicating lateral prefrontal control regions (Frost & McNaughton, 2017; Kable & Glimcher, 2007; McClure, Ericson, Laibson, Loewenstein, & Cohen, 2007; McClure, Laibson, Loewenstein, & Cohen, 2004; Scheres, de Water, & Mies, 2013). The striatum in particular is thought to be critically involved in steeper temporal discounting in adults. Enhanced activation in the striatal subdivisions (i.e., ventral striatum [VS], caudate, and putamen) has been associated with more frequent selection of SS options in adult temporal discounting studies (Kim & Im, 2018; Luo, Ainslie, Giragosian, & Monterosso, 2009; McClure, et al., 2007; McClure, et al., 2004). Further, adult studies provide evidence for specific contributions of the striatal subdivisions, with the VS signaling preference and predicting rewards and the caudate evaluating competing reward options during temporal decision-making (Frost & McNaughton, 2017; Kim & Im, 2018).

Yet the relevance of these discoveries to adolescents remains unclear. A substantial body of work provides evidence of functional differences between the brains of adults and adolescents, reflecting the rapid neurodevelopment that occurs during the adolescent period (e.g., Casey, Getz, & Galvan, 2008; Rubia, 2013). To date, few neuroimaging studies have examined temporal discounting in adolescents—with even fewer focused on early adolescents—and many questions remain about its underlying neurobiology (e.g., (van den Bos, Rodriguez, Schweitzer, & McClure, 2015)). Moreover, the age ranges of the adolescent participants have varied across the existing studies, and much of this work has relied on atypical (e.g., adolescents in substance abuse treatment, adolescents in the juvenile justice system) or all-male (Christakou, Brammer, & Rubia, 2011; Gardiner, et al., 2018; Stanger, et al., 2013). As described in more detail in Table 1, a handful of studies in typically-developing adolescents suggest a role for the striatum in adolescent temporal discounting (Christakou, et al., 2011; de Water, et al., 2017). In the study by Christakou and colleagues (2011), in an all-male sample of adolescents between 12 and 17 years and adults between 18 and 31 years, younger age was associated with steeper discounting and increased activation in the ventral striatum/caudate head during immediate choices. In the study by de Water and colleagues (2017) in early adolescents, VS activity was positively correlated with a steeper rate of temporal discounting in the VS (de Water, et al., 2017). Given adult work suggesting functional differences across striatal subdivisions in temporal decision-making (Frost & McNaughton, 2017; Kim & Im, 2018), there may be value in examining the specific contributions of the striatal subdivisions to temporal decision-making in adolescents. However, to date, differences among striatal subdivisions have not yet been rigorously examined in adolescents, precluding an understanding of their specific contributions to temporal decision-making. Examining the specific contributions of each striatal subdivision to temporal decision-making would inform our understanding of specific processes that underlie temporal discounting in early adolescents.

Table 1.

Studies of temporal discounting in typically-developing adolescents

| de Water et al., 2017 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 27 | 19 (and 21 adults) | 58 |

| Female (%) | 52 | 0 | 53 |

| M Age in Years (range) | 14.0 (13–15) | n.r. (12–17) | 14.5 (12–16) |

| Scanner (headcoil) | 3T (32-channel) | 3 T (quadrature) | 1.5 T (32 channel) |

| EPI Resolution (mm) | 3.00 × 3.00 × 3.00 | 3.75 × 3.75 × 5.00 | n.r. |

| Smoothing (mm) | 6 | 8.82 | 5 |

| Normalization | diffeomorphic | affine | n.r. |

| Imaging Approach | whole brain, anatomically defined VS, caudate, putamen | whole brain | whole brain, functionally defined spheres in VS |

| Activation magnitude/direction in striatal and parietofrontal regions | similar | opposite | similar |

Note: A number of other studies have examined temporal discounting in atypical adolescent samples (e.g., Chantiluke et al., 2014; Gardiner et al., 2018; Stanger et al., 2013). n.r. = “not reported”

The goal of the present study was to investigate neural activity during temporal discounting in early adolescents. To maximize sensitivity and specificity, we used a combination of region-of-interest (ROI) and voxelwise analyses. Probabilistic anatomical ROIs included the three major subdivisions of the striatum: the caudate, putamen, and VS (i.e., nucleus accumbens). We anticipated that impulsive choices (SS vs. LL) would be associated with amplified activity in the caudate, putamen, and VS, and that LL choices would be associated with amplified activity in the parietofrontal cortex (de Water, et al., 2017; McClure, et al., 2007; Plichta & Scheres, 2014). We also explored relations between neural function and individual differences in temporal discounting. Based on a meta-analysis of 25 imaging studies of temporal discounting in adults (Schüller, Kuhn, Jessen, & Hu, 2019) and an investigation of temporal discounting in early adolescents (de Water, et al., 2017; Gardiner, et al., 2018), we hypothesized that temporal discounting rate would be positively associated with task-related BOLD signal in striatal subdivisions and parietofrontal regions during reward-related decision-making (SS + LL - baseline).

To generate hypotheses for future research, we also explored relations between neural function and trait-like individual differences in impulsivity. Trait impulsivity reflects a tendency toward immediate action with diminished consideration of future consequences (Moeller, Barratt, Dougherty, Schmitz, & Swann, 2001). Recent adult neuroimaging research suggests that trait (i.e., dispositional) impulsivity is associated with elevated striatal activity to reward (Herbort, et al., 2016; van der Laan, Barendse, Viergever, & Smeets, 2016). For example, trait impulsivity has been associated with increased VS activity during the anticipation of monetary reward (Herbort, et al., 2016) and increased pallidum activity during the presentation of photographs of high-reward junk food (van der Laan, et al., 2016). These adult observations motivate the prediction that adolescents with higher levels of trait impulsivity will show enhanced striatal response during SS compared to LL choices, and perhaps more generally across all trials of the reward decision-making task.

Method

Participants

Thirty racially diverse adolescents were recruited from a larger ongoing study examining problematic and potentially harmful behaviors (e.g., substance use, unsafe sex) in typically developing adolescents. Inclusion criteria required that participants be between the ages of 13 and 15, right-handed, and fluent in English with normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, MRI contraindications, self-reported current psychiatric or lifetime neurological conditions, or current use of psychoactive medication. Three participants were excluded from fMRI analyses: one because of an incidental neurological finding, and two because they rarely chose the SS option (<8%), precluding a meaningful temporal discounting estimate (k; see below). The final sample included 27 early adolescents (14 girls; M = 14 years old, SD = 0.72; 41% Caucasian, and 59% Black/African-American). Guardians provided informed written consent and participants provided written assent. Adolescents and parents were compensated with $50 and a $5 gift card, respectively, for their participation. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland.

General Procedures

Foam inserts were used to minimize potential movement. During scanning, visual stimuli were digitally projected onto a screen mounted at the head-end of the scanner bore and viewed using a mirror mounted on the head-coil. The task was performed using an MRI-compatible, fiber-optic response pad (MRA, Washington, PA). Participant status was continuously monitored from the control room using an MRI-compatible eye-tracker (data not recorded; Eyelink 1000; SR Research, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). Questionnaires were completed after scanning.

Temporal Discounting Paradigm

The fMRI temporal discounting task was adapted from prior work in youth (Christakou, et al., 2011; Hoyle, Stephenson, Palmgreen, Lorch, & Donohew, 2002; Rubia, Halari, Christakou, & Taylor, 2009) and validated in multiple studies (Carlisi, et al., 2016; Carlisi, et al., 2017; Chantiluke, et al., 2014). Experimenters instructed the participants on how to complete the task prior to the first scan. Participants were told that questions would appear on the screen about receiving hypothetical amounts of money in a set amount of time (e.g., $100 in 1 year), with one option on the right and the other option on the left side of the screen. Participants were instructed to indicate their preferred option using a response pad. Participants completed up to 3 scans of the task (20 trials/scan), and usable behavioral and imaging data were available for at least 2 scans for every participant. On each trial, participants selected one of two hypothetical options: a small-immediate reward (‘SS;’ e.g., $63 now) or a larger-delayed reward (‘LL;’ e.g., $100 in 1 year). The magnitude of the SS option was variable and was always available “now.” In contrast, the magnitude of the LL option was fixed at $100, and was available following delays of one week, one month, or one year. SS and LL options were always presented for a maximum of 4 s on the left and right sides of the screen, respectively, to minimize sensorimotor load (Christakou, et al., 2011). After the selected option was indicated, the unselected option disappeared and the selected alternative remained on the screen for 0.5 s. During the inter-trial interval, a fixation cross was presented for 8 – 11.5 s. An adaptive testing algorithm was used to identify the amount at which participants are equally likely to choose the SS and LL options (i.e., the indifference point) (Richards, Mitchell, de Wit, & Seiden, 1997). The algorithm was identical to that employed by Christakou and colleagues (2011) and adjusted the magnitude of the SS option based on the participant’s prior choice for one week, one month, and one year LL delays. The algorithm narrowed the range of the SS magnitude, converging toward the indifference point (Christakou, et al., 2011; Richards, et al., 1997).

Using a well-established hyperbolic discounting function (Mazur, 1987), temporal discounting rates were defined as: k = [(a/v)-1]/d, in which v is the subjective present value of a reward (i.e., the indifference point), a is the reward amount, and d is the delay. The indifference point for each delay was calculated by averaging the two SS trials with the largest immediate option values and the two LL trials with the smallest immediate option values. Individual differences in temporal discounting were estimated by averaging across delay-specific values of k. Higher values of k indicate a steeper rate of delay discounting (i.e., favoring immediate gratification at the expense of greater expected return). All participants showed systematic discounting behavior, as indexed by Johnson and Bickel’s (2008) criteria. A Winsor transformation (5th and 95th percentiles) was used to normalize the distribution of k after excluding a single scan in which the participant failed to respond at least 3 times to each trial type1.

Self-Reported Trait Impulsivity

Trait-like individual differences in impulsivity were assessed using the 19-item I7 Impulsivity Scale (α = 0.78) (Eysenck, Eysenck, & Barrett, 1985). Representative items include “Do you generally do and say things without stopping to think?” and “Do you often buy things on impulse?” Missing data for one participant was imputed using the sample mean. A Winsor transformation (5th and 95th percentiles) was used to normalize the distribution.

MRI Data Acquisition

MRI data were acquired using a Siemens TIM Trio 3 Tesla scanner and 32-channel head-coil. Sagittal T1-weighted anatomical images were acquired using a magnetization-prepared, rapid-acquisition, gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR=1,900 ms; TE=2.32 ms; inversion time=900 ms; flip angle=9°; slice thickness=0.9 mm; in-plane resolution=0.449 × 0.449 mm; matrix=512 × 512; field-of-view=230 × 230). A standard sequence was used to collect oblique-axial (~20° below the AC-PC plane) echo planar imaging (EPI) volumes during three scans of the temporal discounting task (TR=2,200 ms; TE=24 ms; flip angle=78°; slice thickness=3 mm; gap= 0.5 mm; in-plane resolution=3 × 3 mm; matrix=64 × 64; field-of-view=192 × 192; 110 volumes/scan; 4’:08”/scan). To enable fieldmap correction, two oblique-axial spin echo (SE) images were collected in each of two opposing phase-encoding directions (rostral-to-caudal and caudal-to-rostral) at the same location and resolution as the functional volumes (i.e., co-planar; TR=7,220 ms; TE=73 ms).

MRI Data Processing

Anatomical Data Processing.

Methods are similar to those described in recent reports by our group (Hur, et al., 2018; Smith, Monterosso, Wakslak, Bechara, & Read, 2018; Tillman, et al., 2018) and others (Meyer, Padmala, & Pessoa, 2017; Najafi, Kinnison, & Pessoa, 2017) and are only briefly summarized here. T1-weighted images were inhomogeneity-corrected using N4 (Tustison, et al., 2014), brain-extracted, and spatially normalized to the 1-mm MNI152 template using the high-precision diffeomorphic approach implemented in ANTS (Avants, Epstein, Grossman, & Gee, 2008; Avants, et al., 2011; Avants, et al., 2010; Iglesias, Liu, Thompson, & Tu, 2011). Each dataset was visually inspected before and after processing for quality assurance. Fieldmaps were created using FSL (Andersson, Skare, & Ashburner, 2003).

Functional Data Processing.

All volumes were written to standard orientation using FSL and de-spiked and slice-time corrected using AFNI (Cox, 1996). Recent methodological work indicates that de-spiking is more effective than ‘scrubbing’ (Greve & Fischl, 2009; Jo, et al., 2013; Power, Schlaggar, & Petersen, 2015; Siegel, et al., 2014) for attenuating motion-related artifacts. For co-registration of the functional and anatomical images, an average EPI image was created using two-pass motion correction in AFNI. The average image was simultaneously co-registered with the corresponding T1-weighted image in native space and corrected for geometric distortions using the boundary-based cost function implemented in FSL and the fieldmap. The spatial transformations for each volume were concatenated and applied in a single step to minimize incidental spatial smoothing. The transformed images were re-sliced to 2-mm3 (5th-order splines) and spatially smoothed (6-mm FWHM) within the brain mask using AFNI.

fMRI Modeling

fMRI data were modeled using SPM12 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm)) and in-house MATLAB code. At the first level (single-subject), the temporal discounting task was modeled using 3 predictors (SS, LL, and non-response) convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function with latency and dispersion derivatives. Reaction time was used to determine trial duration. Activity during the inter-trial interval served as the implicit baseline. Nuisance variates included 19 estimates of motion (rostral-caudal, dorsal-ventral, left-right, pitch, roll, and yaw lagged by 0–2 volumes; and the final value of the cost function minimized during rigid-body motion correction [negative mutual information with the mean EPI]) and 2 estimates of physiological noise. To attenuate potential physiological nose, white matter (WM) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) signals were identified by thresholding the tissue priors distributed with FSL, as in prior work by our group (Birn, et al., 2014; Tillman, et al., 2018) and others (Coulombe, Erpelding, Kucyi, & Davis, 2016). EPI time-series were orthogonalized with respect to the first 3 right eigenvectors of the data covariance matrix from the WM and CSF compartments (Behzadi, Restom, Liau, & Liu, 2007). Volumes showing significant displacement (volume-to-volume >0.66 mm) were censored. The overall BOLD response was computed by combining coefficients from the canonical HRF and its derivatives (Lindquist & Wager, 2007). The inter-quartile range (IQR) of motion for each scan was calculated and scans an IQR >3 SD (8.6%) were excluded from second-level modelling. In addition, we excluded a single scan in which the participant failed to respond at least 3 times to each trial type.

Hypothesis Testing Strategy

The major aim of the present study was to test the hypothesis that the BOLD signal would be enhanced on trials associated with SS compared to LL choices in the subdivisions of the striatum (i.e., caudate, putamen, and VS) in early adolescents. In addition, we tested the hypothesis that BOLD signal during trials associated with SS compared to LL choices would be enhanced in the parietal cortex and reduced in the lateral prefrontal cortex. Given the integral role of the striatum in temporal discounting and trait impulsivity, hypothesis testing focused on unbiased, anatomically defined, probabilistic striatal ROIs— caudate, VS, and putamen (Tziortzi, et al., 2014)—maximizing statistical power and reproducibility (Poldrack, et al., 2017). The first eigenvalue was extracted separately for each ROI for each hemisphere and then averaged across hemispheres. This enabled us to examine activity associated with monetary decision-making (SS + LL vs. baseline) as well as activity specific to trials associated with impulsive choices (SS - LL) for each sub-region of the striatum. The main task effect was examined using one-sample t-tests. Analyses used standard repeated-measures general linear models (GLMs). Significant interactions were decomposed using focal tests. SPSS v.24 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for ROI and behavioral analyses. Using SPM12, a parallel series of whole-brain voxelwise analyses was performed. Voxelwise analyses were thresholded at p<.05, whole-brain corrected for cluster extent using Gaussian Random Field Theory and a cluster-defining threshold of p=.001 (Eklund, Nichols, & Knutsson, 2016). Clusters were labeled using the Harvard–Oxford and Mai atlases (Desikan, et al., 2006; Frazier, et al., 2005; Mai, 2015; Makris, et al., 2006).

Exploratory Analyses of Individual Differences

We explored relations between k, trait impulsivity, and task-related activity (SS + LL vs. baseline; SS - LL) using both ROI and whole-brain approaches. Standard GLMs were used to examine associations of hemodynamic activity with k and trait impulsivity.

Results

Behavioral Results

The mean rate of temporal discounting on the fMRI temporal discounting task was k=.020 (range= .0011 to .0734). Mean k values from the imaging session were not significantly correlated with self-reported trait impulsivity (r[26]=0.15, p=0.452).

fMRI Results

Reward decision-making activity (SS + LL vs. baseline)

The temporal discounting paradigm elicited robust striatal and cortical activity.

Striatal ROIs.

Consistent with prior work in adults and adolescents, ROI analyses revealed that temporal decision-making (SS + LL vs. baseline) was associated with increased activity in the caudate (t[26]=5.56, p<0.001) and putamen (t[26]=3.65, p=.001). A similar trend was evident in the VS (t[26]=1.80, p=.084). Across the striatum there was a significant effect of subdivision (F[2,52]=7.844, p=.001), with the caudate showing the greatest decision-making activity. Decision-making activity in the caudate was significantly greater than decision-making in the VS (t[26]=3.436, p=.002) and in the putamen (t[26]=3.616, p=.001). Decision-making activity did not differ between the VS and putamen (t[26]=.904, p>.05) (Supplementary Figure 1).

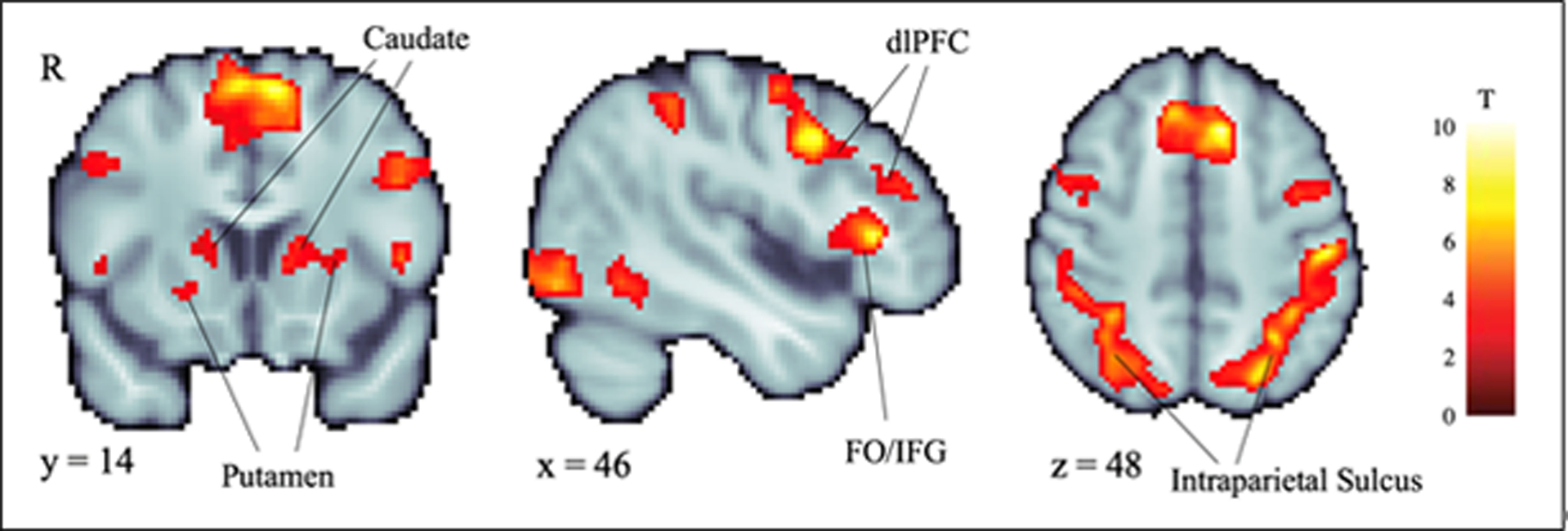

Whole-brain.

As shown in Figure 1, whole-brain voxelwise analyses indicated that reward decision-making (SS + LL vs. baseline) was associated with significantly enhanced activity (p<.05, whole-brain corrected) in several regions, including the caudate, putamen, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), frontal operculum/inferior frontal gyrus, and the cortex surrounding the intraparietal sulcus (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Whole-brain voxelwise analyses indicated that reward decision-making (SS + LL vs. baseline) was associated with significantly enhanced activity (p<.05, whole-brain corrected) in several regions, including the caudate, putamen, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), frontal operculum/inferior frontal gyrus (FO/IFG), and intraparietal sulcus. See Table 2 for detailed results.

Table 2.

Significant whole-brain voxelwise results for overall decision-making activity (SS + LL vs. baseline), p<.05, whole-brain corrected.

| FWE-corrected p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 963 | 44 | 28 | 6 | 10.73 | <0.001 |

| Left Superior Frontal Gyrus | 2,150 | −10 | 22 | 48 | 9.49 | <0.001 |

| Right Middle Frontal Gyrus | 715 | 48 | 8 | 38 | 8.67 | <0.001 |

| Left Posterior Cingulate Gyrus | 100 | −8 | −24 | 34 | 5.88 | 0.001 |

| Right Posterior Cingulate Gyrus | 150 | 8 | −30 | 32 | 6.23 | 0.003 |

| Cerebellum | 136 | 0 | −54 | −36 | 8.41 | 0.005 |

| Right Cerebellum | 128 | 12 | −58 | −48 | 5.56 | 0.007 |

| Right Lateral Occipital Cortex | 22,284 | 34 | −90 | −6 | 13.57 | <0.001 |

Impulsive choice activity (SS – LL)

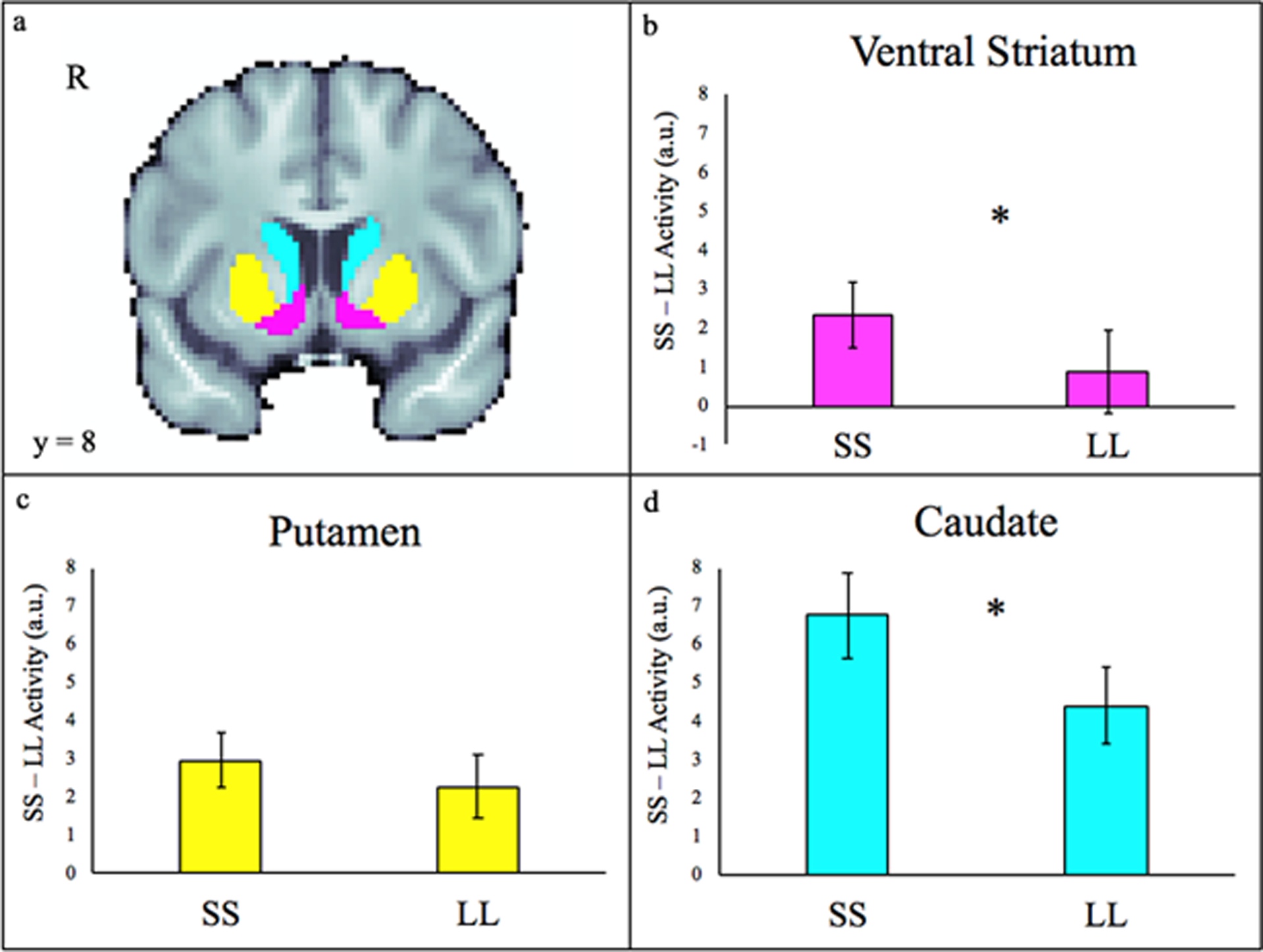

Striatal ROIs.

There was a significant effect of choice type in the striatum, in which activity was greater during impulsive (SS) choices than delayed (LL) choices (F[1,26]=10.552, p=0.003). There also was a significant effect of subdivision (F[2,52]=7.844, p=.001), with the greatest activity in the caudate. As shown in Figure 2, activity associated with SS and LL choices was significantly different in the caudate (t[26]=3.462, p=.002) and in the VS (t[26]=2.211, p=.036). Activity associated with SS and LL choices did not differ significantly in the putamen (t[26]=1.288, p>.05). During impulsive (SS) choices, the caudate showed significantly more activity than the VS (t[26]=3.599, p=.001) and the putamen (t[26]=4.390, p<.001). Activity during SS choices did not differ significantly between the VS and putamen (t[26]=.578, p>.05). During delayed (LL) choices, the caudate showed significantly more activity than the VS (t[26]=2.989, p=.006) and the putamen (t[26]=2.359, p=.026). Activity during LL choices did not differ significantly between the VS and putamen (t[26]=1.075, p>.05).

Figure 2.

ROI results. a. Striatal ROIs are displayed in panel a. The caudate is depicted in cyan, the putamen in yellow, and the VS (nucleus accumbens) in magenta. On average, trials marked by impulsive choices (SS) were associated with significantly greater activity (p<.05) than trials marked by the delay of gratification (LL) in the ventral striatum (b) and the caudate (d), but not in the putamen (c). Error bars depict the standard error of the mean.

Whole-brain.

Whole-brain voxelwise analyses did not detect any regions showing a significant whole-brain corrected effect of choice (SS - LL).

Exploratory analyses of individual differences in temporal discounting (k)

Individual differences in temporal discounting (k) were not significantly associated with task-related activity in either ROI or whole-brain regression analyses.

Exploratory analyses of individual differences in trait impulsivity

Striatal ROIs.

ROI analyses did not detect significant relations between trait impulsivity and variation in decision-making activity (SS + LL vs. baseline), p>0.05.

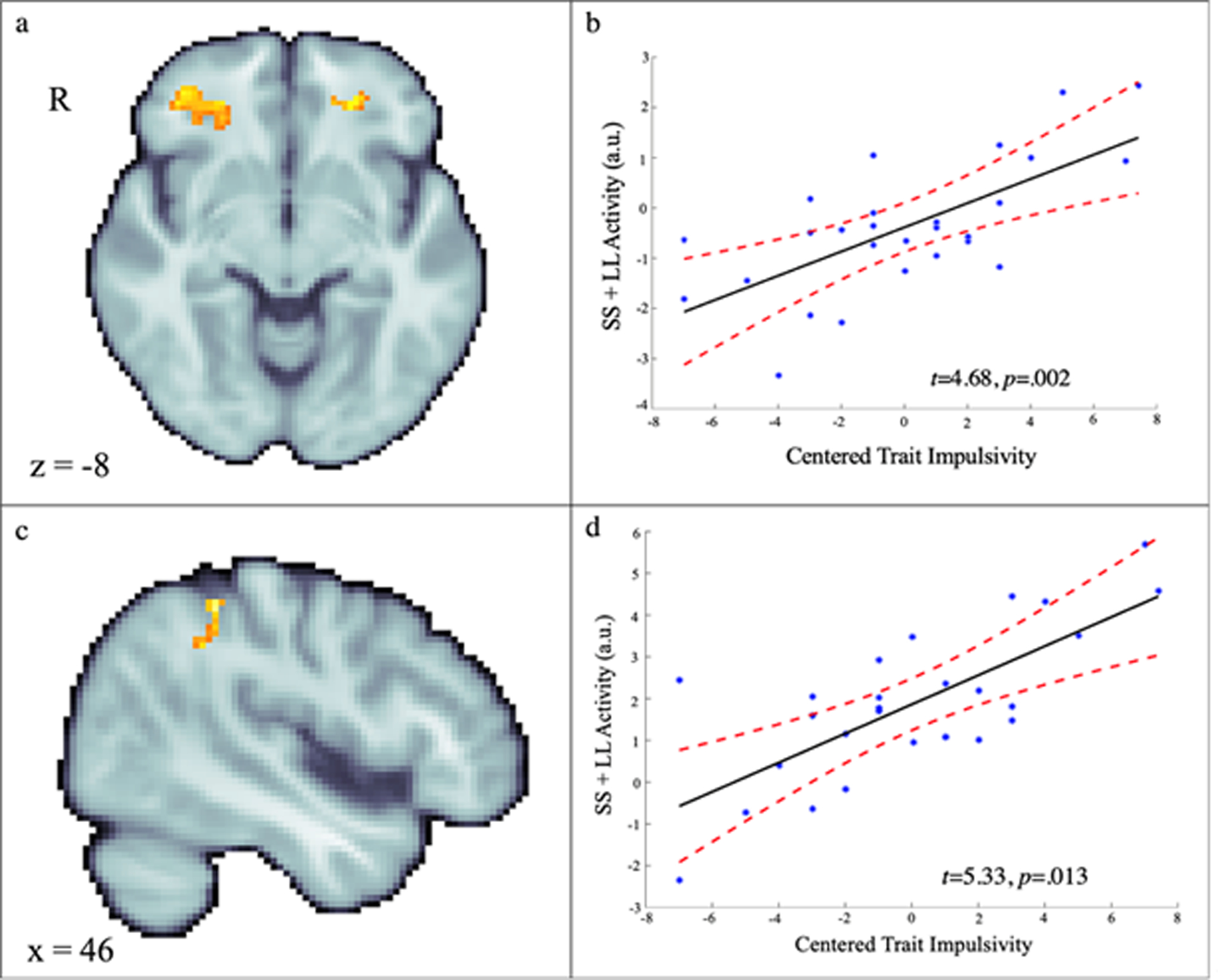

Whole-brain.

Whole-brain voxelwise regression analyses revealed that adolescents who view themselves as generally more impulsive show heightened decision-making activity (SS + LL vs. baseline) in the bilateral orbitofrontal cortex and right supramarginal gyrus (Figure 3 and Table 3).

Figure 3.

Voxelwise relations between self-reported trait impulsivity and reward decision-making activity (SS + LL vs. baseline). Adolescents with higher levels of trait impulsivity showed greater activity in bilateral anterior orbital gyrus (a, b) and right supramarginal gyrus (c, d). The scatterplots depict relations at the peak voxels for illustrative purposes. See Table 3 for detailed results.

Table 3.

Significant voxelwise relations with trait impulsivity, p<.05, whole-brain corrected.

| FWE-corrected p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS + LL vs. Baseline | |||||||

| Left Anterior Orbital Gyrus | 124 | −24 | 42 | −4 | 5.92 | 0.008 | |

| Right Anterior Orbital Gyrus | 160 | 26 | 30 | −10 | 4.68 | 0.002 | |

| Right Supramarginal Gyrus | 114 | 46 | −40 | 50 | 5.33 | 0.013 | |

| SS - LL | |||||||

| Right Middle Frontal Gyrus | 136 | 42 | 12 | 52 | 5.77 | 0.003 | |

| Right Inferior Parietal Cortex | 105 | 42 | −36 | 34 | −4.79 | 0.015 | |

| Left Inferior Parietal Cortex | 141 | −42 | −40 | 28 | −5.85 | 0.003 |

Exploratory analyses of individual differences in trait impulsivity

Striatal ROIs.

ROI analyses indicated that more dispositionally impulsive adolescents showed enhanced activity in the putamen during impulsive decision-making (SS - LL; ß=.425, t[25]=2.30, p=0.03). When controlling for k, the association between trait impulsivity and putamen activity remained significant (p=.03). Significant relations were not evident for the caudate or VS, p>.05 (Figure 2).

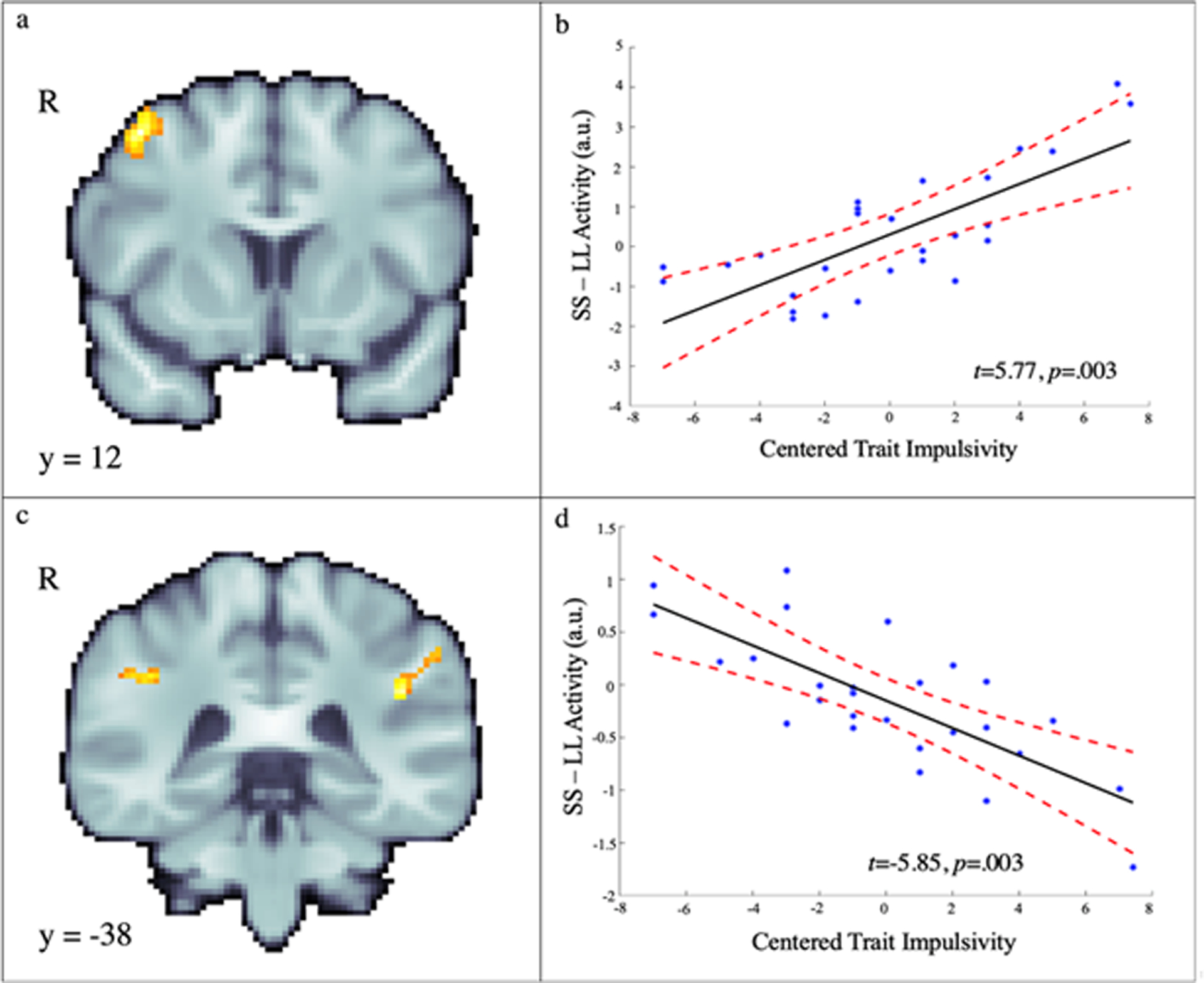

Whole-brain.

Whole-brain voxelwise regression analyses showed that dispositionally impulsive adolescents tended to show amplified activity in the right dlPFC (middle frontal gyrus) and attenuated activity in the parietal cortex (supramarginal gyrus) when selecting immediate compared to delayed reward (SS – LL; Figure 4 and Table 3).

Figure 4.

Voxelwise relations between trait impulsivity and choice-related activity (SS-LL). Adolescents who endorsed higher levels of trait impulsivity showed significantly greater activity in the right middle frontal gyrus (i.e., dlPFC) during SS choices (a, b) and significantly greater activity in the bilateral supramarginal gyrus during LL choices (c, d). The scatterplots depict relations at the peak voxels for illustrative purposes. See Table 3 for detailed results.

Discussion

Steeper rates of temporal discounting contribute to maladaptive choices, including drug and alcohol use and unsafe sex (Amlung, et al., 2017; Lee, et al., 2014; Moody, et al., 2016)—yet, there is a relative paucity of research examining neurocomputational processes in adolescence (Casey, Jones, et al., 2008; Steinberg, 2008) (Table 1). Here we leveraged a well-established fMRI paradigm to rigorously examine striatal engagement during temporal decision-making in early adolescents. ROI analyses revealed significantly greater hemodynamic activity in the VS and caudate when early adolescents made impulsive choices. Furthermore, adolescents who indicated that they were more impulsive in their daily lives tended to show greater BOLD response in the putamen when selecting immediate compared to delayed reward (SS – LL). Finally, trait impulsivity was associated with greater activation during SS choices in the dlPFC, and with greater activation during LL choices in the supramarginal gyrus, a region of the parietal cortex. We discuss each of the main findings below.

First, our finding that BOLD response was greater in the VS and caudate during SS compared to LL choices supports our a priori hypothesis and is consistent with previous research in adults and adolescents (e.g., (Christakou, et al., 2011; Kim & Im, 2018; McClure, et al., 2007; McClure, et al., 2004)). Although striatal activation during temporal-decision-making was evident in the whole-brain analyses in our study, the significant effect of choice type (SS-LL) was only evident in the striatal ROI analyses—a discrepancy that likely reflects the greater power afforded by the ROI approach.

Work in adults demonstrates roles for the VS in signaling preference and predicting rewards (Frost & McNaughton, 2017; Kim & Im, 2018). Compared to the VS, the dorsal striatum’s role in temporal discounting has been relatively understudied to date (Kim & Im, 2018). Research attention has recently shifted towards examining the role of the dorsal striatum in temporal discounting, which may provide a new avenue for understanding the construct (Kim & Im, 2018). The dorsal striatum has been implicated in action selection in decision-making studies, with the caudate subdivision contributing to flexible goal-directed actions and the putamen subdivision contributing to habitual actions (Balleine, Delgado, & Hikosaka, 2007; Kim & Im, 2018; Yin & Knowlton, 2006). During temporal decision-making, the caudate subdivision may contribute to the valuation of competing reward options (i.e. SS, LL; (Kim & Im, 2018)). The greater activation observed in our study during SS choices compared to LL choices in the VS and caudate may suggest that SS rewards are more strongly preferred and highly valued in early adolescents. As such, our study provides insight into associations between impulsive choices and striatal subdivision activation in early adolescents.

Second, the positive association between trait impulsivity and greater activation during SS trials in the bilateral putamen (SS – LL) is consistent with previous work in adults demonstrating greater putamen activation during the anticipation of SS rewards relative to LL rewards (Kim & Im, 2018; Luo, et al., 2009). Work in adults indicates that the putamen is involved in habit formation and the transition to habitual decisions that are insensitive to outcomes (Kim & Im, 2018). The present finding may suggest that a habitual decision-making process contributes to SS choices in early adolescents with higher trait impulsivity. Interestingly, the association between dispositional impulsivity and activation during SS choices was specific to the putamen, a subdivision underlying habitual decisions, while the effect of choice type (SS-LL) was specific to the VS and caudate subdivisions, which underlie preference signaling and reward valuation, respectively. Therefore, the specificity of our findings with respect to temporal discounting and trait impulsivity are concordant with the putative roles of each striatal subdivision in decision-making. Some studies in adults suggest that activation in the putamen during temporal discounting may be similar to activation in the caudate (Kim & Im, 2018; Prevost, Pessiglione, Metereau, Clery-Melin, & Dreher, 2010; Wittmann, Leland, & Paulus, 2007), although more research is needed to differentiate the roles of the dorsal striatal subdivisions. Our findings may suggest that the striatal subdivisions are associated with distinct aspects of impulsive decisions in early adolescents; VS and caudate may contribute to a greater preference and valuation of SS choices, while putamen may contribute to a habitual decision-making process in more impulsive early adolescents.

Last, we report that trait impulsivity was positively associated with greater activation during LL choices in the supramarginal gyrus region of the parietal cortex and with greater activation during SS choices in the middle frontal gyrus (i.e., dlPFC). Our finding that trait impulsivity was associated with greater relative parietal cortex activation during LL trials is consonant with the correlation between temporal discounting rate and parietal cortex activation reported by de Water and colleagues in adolescents (2017). Work in adults shows that greater engagement of the parietal cortex during temporal discounting tasks is associated with aspects of delay consideration (Frost & McNaughton, 2017), including imagining the future (i.e., mental time travel (Boyer, 2008; Schacter, et al., 2012), representing the subjective value of the delayed reward (Prevost, et al., 2010), and choosing the delayed reward (Christakou, et al., 2011; Wittmann, et al., 2007). Activation in the supramarginal gyrus region of the parietal cortex during temporal decision-making may reflect the relative subjective value of the chosen reward (Massar, Libedinsky, Weiyan, Huettel, & Chee, 2015). A negative correlation between supramarginal gyrus activation and a tendency to choose immediate rewards was reported in previous research with adults (e.g. (Boettiger, et al., 2007)). Our finding that trait impulsivity was positively associated with greater activation in the supramarginal gyrus during LL choices may suggest that dispositionally impulsive adolescents require more effort to delay gratification. Activity in the middle frontal gyrus has been associated with the subjective value of offered gains and delayed (i.e., LL) choices (Hare, Hakimi, & Rangel, 2014), as well as with engagement in temporal decision-making, regardless of choice type (Blain, Hollard, & Pessiglione, 2016; Frost & McNaughton, 2017). Our finding that trait impulsivity was positively associated with greater activation in the middle frontal gyrus (i.e., dlPFC) during SS choices could suggest that early adolescents who view themselves as more impulsive tend to value immediate rewards more than delayed ones.

The competing neurobehavioral decision systems (CDNS) theory (Bickel, Snider, Quisenberry, Stein, & Hanlon, 2016) posits that choice results from the relative control between two opposing systems—the impulsive decision system (which includes the striatum) and the executive decision system (which includes the parietal lobes). In this view, the positive association between trait impulsivity and activation in a component of the executive system (i.e., the supramarginal gyrus) may suggest that delaying gratification requires more effort in early adolescents with higher levels of trait impulsivity. Broadly, we observed a more similar, rather than opposing, pattern of activation between the impulsive and executive systems in our study, which likely reflects the young age of our early adolescent sample. The imbalance model of brain development proposes that reward-related subcortical brain regions and connections develop earlier than do connections supporting prefrontal control, resulting in a greater reliance on motivational subcortical regions during adolescence (Somerville & Casey, 2010). Despite the cross-sectional nature of our study, the greater striatal activation evident during smaller-sooner choices in our early adolescent sample is consistent with this model. Our findings suggest that trait impulsivity may augment this imbalance.

Limitations and Future Challenges

The present results provide preliminary insights into the neural systems underlying reward-related choice in early adolescence. A limitation of the study is its relatively small sample size (Poldrack, et al., 2017; Schönbrodt & Perugini, 2013). A key challenge for the future will be to assess the reproducibility of these discoveries in larger and more diverse samples, which also would have the statistical power to examine whether the effects are moderated by gender, race/ethnicity, and family income. Prospective-longitudinal designs and research examining neurobiological changes underlying interventions that reduce impulsive behaviors (e.g., personality-targeted interventions (Conrod, 2016)) will be necessary to clarify the causal contribution of the regions highlighted by our results to the emergence of impulsive and harmful behaviors in adolescence. Prospective work will be necessary to fully understand how this pattern of brain function develops and matures across the lifespan.

Conclusions

In sum, our results provide an important first glimpse at the distributed neural circuitry underlying impulsive decision making in early adolescence. Our results demonstrate significantly greater striatal engagement during impulsive choices, compared to deferred gratification, in early adolescents. Our results also demonstrate a positive association between trait impulsivity and greater activation during SS choices in bilateral putamen and a more nuanced pattern in cortex, with activation in the dlPFC (i.e., middle frontal gyrus) mirroring striatum, and activation in supramarginal gyrus showing the opposite effect. These results suggest that trait impulsivity is associated with activity during temporal decision-making in regions that contribute to habitual decisions, reward valuation, and delay consideration in early adolescence. More research is needed to determine whether and how trait impulsivity impacts temporal discounting; our preliminary findings suggest several fruitful avenues to explore in future prospective studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge critical feedback and assistance from the reviewers, J. Blanchard, J. Kinnison, J. Soldinger, and personnel from the Maryland Neuroimaging Center. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R00DA038589, DA040717, and MH107444) and University of Maryland.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

KR has received grants from Takeda (prior Shire) pharmaceuticals for another project. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Data Sharing

Key statistical maps have been or will be uploaded to NeuroVault.org.

Exploratory analyses revealed robust relations between k and self-reported discounting (r[25]=.69, p<.001) on the Monetary Choice Questionnaire (Kirby, Petry, & Bickel, 1999), underscoring the validity of our approach.

References

- Amlung M, Vedelago L, Acker J, Balodis I, & MacKillop J (2017). Steep delay discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis of continuous associations. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 112, 51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JL, Skare S, & Ashburner J (2003). How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage, 20, 870–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, & Gee JC (2008). Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med Image Anal, 12, 26–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, & Gee JC (2011). A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage, 54, 2033–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants BB, Yushkevich P, Pluta J, Minkoff D, Korczykowski M, Detre J, & Gee JC (2010). The optimal template effect in hippocampus studies of diseased populations. Neuroimage, 49, 2457–2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, Delgado MR, & Hikosaka O (2007). The role of the dorsal striatum in reward and decision-making. J Neurosci, 27, 8161–8165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzadi Y, Restom K, Liau J, & Liu TT (2007). A component based noise correction method (CompCor) for BOLD and perfusion based fMRI. Neuroimage, 37, 90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, & Marsch LA (2001). Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction, 96, 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Snider SE, Quisenberry AJ, Stein JS, & Hanlon CA (2016). Competing neurobehavioral decision systems theory of cocaine addiction: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Prog Brain Res, 223, 269–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birn RM, Shackman AJ, Oler JA, Williams LE, McFarlin DR, Rogers GM, Shelton SE, Alexander AL, Pine DS, Slattery MJ, Davidson RJ, Fox AS, & Kalin NH (2014). Evolutionarily conserved prefrontal-amygdalar dysfunction in early-life anxiety. Mol Psychiatry, 19, 915–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blain B, Hollard G, & Pessiglione M (2016). Neural mechanisms underlying the impact of daylong cognitive work on economic decisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 113, 6967–6972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettiger CA, Mitchell JM, Tavares VC, Robertson M, Joslyn G, D’Esposito M, & Fields HL (2007). Immediate reward bias in humans: fronto-parietal networks and a role for the catechol-O-methyltransferase 158(Val/Val) genotype. J Neurosci, 27, 14383–14391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer P (2008). Evolutionary economics of mental time travel? Trends Cogn Sci, 12, 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisi CO, Chantiluke K, Norman L, Christakou A, Barrett N, Giampietro V, Brammer M, Simmons A, & Rubia K (2016). The effects of acute fluoxetine administration on temporal discounting in youth with ADHD. Psychol Med, 46, 1197–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisi CO, Norman L, Murphy CM, Christakou A, Chantiluke K, Giampietro V, Simmons A, Brammer M, Murphy DG, Mataix-Cols D, & Rubia K (2017). Comparison of neural substrates of temporal discounting between youth with autism spectrum disorder and with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychol Med, 47, 2513–2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Getz S, & Galvan A (2008). The adolescent brain. Dev. Rev, 28, 62–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, & Hare TA (2008). The Adolescent Brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1124, 111–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantiluke K, Christakou A, Murphy CM, Giampietro V, Daly EM, Ecker C, Brammer M, Murphy DG, Consortium MA, & Rubia K (2014). Disorder-specific functional abnormalities during temporal discounting in youth with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism and comorbid ADHD and Autism. Psychiatry Res, 223, 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakou A, Brammer M, & Rubia K (2011). Maturation of limbic corticostriatal activation and connectivity associated with developmental changes in temporal discounting. Neuroimage, 54, 1344–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ (2016). Personality-Targeted Interventions for Substance Use and Misuse. Curr Addict Rep, 3, 426–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe MA, Erpelding N, Kucyi A, & Davis KD (2016). Intrinsic functional connectivity of periaqueductal gray subregions in humans. Hum Brain Mapp, 37, 1514–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW (1996). AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res, 29, 162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Water E, Mies GW, Figner B, Yoncheva Y, van den Bos W, Castellanos FX, Cillessen AHN, & Scheres A (2017). Neural mechanisms of individual differences in temporal discounting of monetary and primary rewards in adolescents. Neuroimage, 153, 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, & Killiany RJ (2006). An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage, 31, 968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund A, Nichols TE, & Knutsson H (2016). Cluster failure: Why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 7900–7905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SB, Eysenck HJ, & Barrett P (1985). A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Personality and individual differences, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier JA, Chiu S, Breeze JL, Makris N, Lange N, Kennedy DN, Herbert MR, Bent EK, Koneru VK, Dieterich ME, Hodge SM, Rauch SL, Grant PE, Cohen BM, Seidman LJ, Caviness VS, & Biederman J (2005). Structural brain magnetic resonance imaging of limbic and thalamic volumes in pediatric bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry, 162, 1256–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R, & McNaughton N (2017). The neural basis of delay discounting: A review and preliminary model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 79, 48–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner CK, Karoly HC, Thayer RE, Gillman AS, Sabbineni A, & Bryan AD (2018). Neural activation during delay discounting is associated with 6-month change in risky sexual behavior in adolescents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52, 356–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, & Myerson J (2004). A Discounting Framework for Choice With Delayed and Probabilistic Rewards. Psychological bulletin, 130, 769–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve DN, & Fischl B (2009). Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage, 48, 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton KR, Mitchell MR, Wing VC, Balodis IM, Bickel WK, Fillmore M, Lane SD, Lejuez CW, Littlefield AK, Luijten M, Mathias CW, Mitchell SH, Napier TC, Reynolds B, Schutz CG, Setlow B, Sher KJ, Swann AC, Tedford SE, White MJ, Winstanley CA, Yi R, Potenza MN, & Moeller FG (2015). Choice impulsivity: Definitions, measurement issues, and clinical implications. Personal Disord, 6, 182–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare TA, Hakimi S, & Rangel A (2014). Activity in dlPFC and its effective connectivity to vmPFC are associated with temporal discounting. Front Neurosci, 8, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbort MC, Soch J, Wustenberg T, Krauel K, Pujara M, Koenigs M, Gallinat J, Walter H, Roepke S, & Schott BH (2016). A negative relationship between ventral striatal loss anticipation response and impulsivity in borderline personality disorder. Neuroimage Clin, 12, 724–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, & Donohew RL (2002). Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personality and individual differences, 32, 401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Hur J, Kaplan CM, Smith JF, Bradford DE, Fox AS, Curtin JJ, & Shackman AJ (2018). Acute alcohol administration dampens central extended amygdala reactivity. Scientific reports, 8, 16702–16702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias JE, Liu CY, Thompson PM, & Tu Z (2011). Robust brain extraction across datasets and comparison with publicly available methods. IEEE Trans Med Imaging, 30, 1617–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo HJ, Gotts SJ, Reynolds RC, Bandettini PA, Martin A, Cox RW, & Saad ZS (2013). Effective Preprocessing Procedures Virtually Eliminate Distance-Dependent Motion Artifacts in Resting State FMRI. Journal of Applied Mathematics, 2013, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable JW, & Glimcher PW (2007). The neural correlates of subjective value during intertemporal choice. Nat Neurosci, 10, 1625–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, & Im HI (2018). The role of the dorsal striatum in choice impulsivity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, & Bickel WK (1999). Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental psychology: general, 128, 78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FS, Heimer H, Giedd JN, Lein ES, Šestan N, Weinberger DR, & Casey BJ (2014). Mental health. Adolescent mental health--opportunity and obligation. Science (New York, N.Y.), 346, 547–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist MA, & Wager TD (2007). Validity and power in hemodynamic response modeling: a comparison study and a new approach. Hum Brain Mapp, 28, 764–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Ainslie G, Giragosian L, & Monterosso JR (2009). Behavioral and neural evidence of incentive bias for immediate rewards relative to preference-matched delayed rewards. J Neurosci, 29, 14820–14827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai K, Majtanik M, Paxinos G (2015). Atlas of the Human Brain (4th edition ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Makris N, Goldstein JM, Kennedy D, Hodge SM, Caviness VS, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT, & Seidman LJ (2006). Decreased volume of left and total anterior insular lobule in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res, 83, 155–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massar SA, Libedinsky C, Weiyan C, Huettel SA, & Chee MW (2015). Separate and overlapping brain areas encode subjective value during delay and effort discounting. Neuroimage, 120, 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur J (1987). An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement (Vol. 5). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Ericson KM, Laibson DI, Loewenstein G, & Cohen JD (2007). Time discounting for primary rewards. J Neurosci, 27, 5796–5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Laibson DI, Loewenstein G, & Cohen JD (2004). Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Science, 306, 503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer C, Padmala S, & Pessoa L (2017). Tracking dynamic threat imminence. bioRxiv, 183798. [Google Scholar]

- Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Patrick ME (2019). Trends in Adolescent Vaping, 2017–2019. N Engl J Med, 381, 1490–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, & Swann AC (2001). Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am. J. Psychiatry, 158, 1783–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody L, Franck C, Hatz L, & Bickel WK (2016). Impulsivity and polysubstance use: A systematic comparison of delay discounting in mono-, dual-, and trisubstance use. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol, 24, 30–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi M, Kinnison J, & Pessoa L (2017). Dynamics of Intersubject Brain Networks during Anxious Anticipation. Front Hum Neurosci, 11, 552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plichta MM, & Scheres A (2014). Ventral-striatal responsiveness during reward anticipation in ADHD and its relation to trait impulsivity in the healthy population: a meta-analytic review of the fMRI literature. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 38, 125–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Baker CI, Durnez J, Gorgolewski KJ, Matthews PM, Munafo MR, Nichols TE, Poline JB, Vul E, & Yarkoni T (2017). Scanning the horizon: towards transparent and reproducible neuroimaging research. Nat Rev Neurosci, 18, 115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Schlaggar BL, & Petersen SE (2015). Recent progress and outstanding issues in motion correction in resting state fMRI. Neuroimage, 105, 536–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevost C, Pessiglione M, Metereau E, Clery-Melin ML, & Dreher JC (2010). Separate valuation subsystems for delay and effort decision costs. J Neurosci, 30, 14080–14090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rew L, Horner SD, & Brown A (2011). Health-risk behaviors in early adolescence. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs, 34, 79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JB, Mitchell SH, de Wit H, & Seiden LS (1997). Determination of discount functions in rats with an adjusting-amount procedure. J Exp Anal Behav, 67, 353–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K (2013). Functional brain imaging across development. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22, 719–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Halari R, Christakou A, & Taylor E (2009). Impulsiveness as a timing disturbance: neurocognitive abnormalities in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder during temporal processes and normalization with methylphenidate. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 364, 1919–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Addis DR, Hassabis D, Martin VC, Spreng RN, & Szpunar KK (2012). The future of memory: remembering, imagining, and the brain. Neuron, 76, 677–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, de Water E, & Mies GW (2013). The neural correlates of temporal reward discounting. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci, 4, 523–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönbrodt FD, & Perugini M (2013). At what sample size do correlations stabilize? J Res Pers, 47, 609–612. [Google Scholar]

- Schüller CB, Kuhn J, Jessen F, & Hu X (2019). Neuronal correlates of delay discounting in healthy subjects and its implication for addiction: an ALE meta-analysis study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 45, 51–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JS, Power JD, Dubis JW, Vogel AC, Church JA, Schlaggar BL, & Petersen SE (2014). Statistical improvements in functional magnetic resonance imaging analyses produced by censoring high-motion data points. Hum Brain Mapp, 35, 1981–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikora R (2016). Risk behaviors at late childhood and early adolescence as predictors of depression symptoms. 17, 173. [Google Scholar]

- Smith BJ, Monterosso JR, Wakslak CJ, Bechara A, & Read SJ (2018). A meta-analytical review of brain activity associated with intertemporal decisions: Evidence for an anterior-posterior tangibility axis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 86, 85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, & Casey BJ (2010). Developmental neurobiology of cognitive control and motivational systems. Curr Opin Neurobiol, 20, 236–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Elton A, Ryan SR, James GA, Budney AJ, & Kilts CD (2013). Neuroeconomics and adolescent substance abuse: individual differences in neural networks and delay discounting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 52, 747–755 e746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev. Rev, 28, 78–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman RM, Stockbridge MD, Nacewicz BM, Torrisi S, Fox AS, Smith JF, & Shackman AJ (2018). Intrinsic functional connectivity of the central extended amygdala. Hum Brain Mapp, 39, 1291–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tustison NJ, Cook PA, Klein A, Song G, Das SR, Duda JT, Kandel BM, van Strien N, Stone JR, Gee JC, & Avants BB (2014). Large-scale evaluation of ANTs and FreeSurfer cortical thickness measurements. Neuroimage, 99, 166–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tziortzi AC, Haber SN, Searle GE, Tsoumpas C, Long CJ, Shotbolt P, Douaud G, Jbabdi S, Behrens TE, Rabiner EA, Jenkinson M, & Gunn RN (2014). Connectivity-based functional analysis of dopamine release in the striatum using diffusion-weighted MRI and positron emission tomography. Cereb Cortex, 24, 1165–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bos W, Rodriguez CA, Schweitzer JB, & McClure SM (2015). Adolescent impatience decreases with increased frontostriatal connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, E3765–E3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan LN, Barendse MEA, Viergever MA, & Smeets PAM (2016). Subtypes of trait impulsivity differentially correlate with neural responses to food choices. Behav Brain Res, 296, 442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Leland DS, & Paulus MP (2007). Time and decision making: differential contribution of the posterior insular cortex and the striatum during a delay discounting task. Experimental Brain Research, 179, 643–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HH, & Knowlton BJ (2006). The role of the basal ganglia in habit formation. Nat Rev Neurosci, 7, 464–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.