Highlights

-

•

Better MRI sequences and technology increase its utility in early stage lung cancer.

-

•

MRI can also provide functional data to aid in diagnosis and response evaluation.

-

•

MRI-guidance can improve radiotherapy in lung cancer despite physical challenges.

-

•

Real-time tracking and better soft tissue contrast also facilitate adaptive therapy.

Keywords: Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging, Lung neoplasms, Magnetic resonance imaging, Radiotherapy, Image-guided

Abstract

Despite magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) being a mainstay in the oncologic care for many disease sites, it has not routinely been used in early lung cancer diagnosis, staging, and treatment. While MRI provides improved soft tissue contrast compared to computed tomography (CT), an advantage in multiple organs, the physical properties of the lungs and mediastinum create unique challenges for lung MRI. Although multi-detector CT remains the gold standard for lung imaging, advances in MRI technology have led to its increased clinical relevance in evaluating early stage lung cancer. Even though positron emission tomography is used more frequently in this context, functional MR imaging, including diffusion-weighted MRI and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, are emerging as useful modalities for both diagnosis and evaluation of treatment response for lung cancer. In parallel with these advances, the development of combined MRI and linear accelerator devices (MR-linacs), has spurred the integration of MRI into radiation treatment delivery in the form of MR-guided radiotherapy (MRgRT). Despite challenges for MRgRT in early stage lung cancer radiotherapy, early data utilizing MR-linacs shows potential for the treatment of early lung cancer. In both diagnosis and treatment, MRI is a promising modality for imaging early lung cancer.

1. Introduction

Despite many recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer, it remains the most common cause of cancer death worldwide; accounting for 18% of cancer-related deaths [1]. Much work has been done to diagnose these malignancies early due to the wide discrepancy in survival between early stage and locally advanced lung cancer [2]. Low dose computed tomography (CT) is currently the standard of care in screening patients at high risk for lung cancer. Such programs have been implemented with moderate success, leading to adoption in the United States [3] and further consideration in Europe [4]. In addition to the refinement of CT technology, the acquisition of functional information in the form of positron emission tomography (PET) has become an indispensable adjunct to complete staging and diagnosis [5]. Despite the fact that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become a mainstay in the imaging of other disease sites [6], MRI has not routinely been used as a part of the workflow in early lung cancer diagnosis, staging, treatment, or surveillance. In this paper, we will discuss the potential role of MRI in the diagnosis and treatment of early stage lung cancer.

2. Barriers to lung MRI

While in other body sites MRI provides excellent soft tissue contrast not achievable with computed tomography (CT), the physical properties of the lungs and mediastinum create unique challenges in the use of diagnostic MRI (Fig. 1). First, the low tissue density and high air content of the lung drastically reduces the signal to noise ratio (SNR) because the MR signal is directly proportional to proton density [7]. Using a higher magnetic field (B0) can theoretically improve SNR, but unfortunately it would exacerbate susceptibility artifacts due to magnetic field inhomogeneities caused by omnipresent microscopic tissue-air interfaces smaller than standard voxel sizes [7].

Fig. 1.

Overview of challenges and advantages for the use of lung MRI in early lung cancer diagnosis and radiotherapy. CT = computed tomography; PET = positron-emission tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

In addition, motion from both the cardiac and respiratory cycles may cause ghosting artifacts on the MR images. Respiratory-induced image degradation can be ameliorated by breath-holding, however limiting acquisition time to encompass a breath-hold may compromise other parameters, such as spatial resolution. In addition, patients with lung cancer may have other comorbidities making breath-hold difficult. To provide adequate image quality, certain sequences require a longer acquisition time than would be practical for a patient to hold their breath (around 20 s). The alternative of splitting such sequences into multiple breath-holds is also fraught with the addition of more artifacts from the need to combine potentially mismatching images from non-reproducible breath-holds [8]. Breath-hold reproducibility can be improved by using respiratory monitoring, patient coaching to achieve a displayed respiratory level, or active breathing control devices which can induce breath-holds at predetermined respiratory volumes. However, these devices may also require modifications for MR application [9]. Respiratory gating using bellows systems or navigator techniques can reduce breathing artifacts, while electrocardiogram (ECG) or pulse oximeter gating can reduce artifacts due to cardiac motion. Nevertheless, application of these techniques may substantially increase patient scanning time [10]. In addition to the physical limitations of MRI, many competing protocols exist without standardization, complicating both the acquisition and interpretation of lung MRIs [11]. Some patients may also not be eligible for MRIs due to the presence of non-compatible implants. Lastly, many patients also have difficulties with extended breath holds, the length of studies, and claustrophobia.

Because MRI utilizing lower static magnetic field strength presents theoretical advantages to lung imaging by reducing susceptibility artifacts despite theoretical reductions in SNR, some work has been done investigating lung MRI at lower magnetic fields [12]. With the evolution of image correction algorithms, open low-field MRIs have been shown to provide adequate images for radiation treatment planning in multiple disease sites, including in lung [13].

3. Advances in MRI technology

Despite the above barriers, MRI presents advantages over the current regimen of CT and PET/CT, including the ability to forgo the radioactive contrast agent administration necessary in PET/CT [14]. Advances in MRI technology have allowed for its increased clinical relevance in evaluating lung cancer. For example, turbo-spin echo (TSE) is a fast MRI sequence which is robust to susceptibility differences between air and lung tissues and allows for equivalent malignant nodule detection rate to MDCT [15]. A Half-Fourier single-shot TSE (HASTE) sequence, which improves scan times further by taking advantage of certain “mirror-image” properties of the raw MR data (k-space) reduces the influence of respiratory and cardiac motion artifact [16]. Although short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences with TSE (turbo STIR) for fat signal suppression is typically used for better delineation of soft tissue and local tumor spread, it can be employed to enhance contrast for pulmonary lesions without unreasonably prolonging breath hold times. However, these sequences remain susceptible to flow artifact from significant blood flow throughout the lungs, which can additionally be mitigated by the use of black-blood sequences by using a double recovery sequence, especially when cardiac gating is inadequate [17]. Aside from TSE-based sequences, other groups have shown the viability of volumetric interpolated breath-hold examinations (VIBE), which is a radio-frequency spoiled 3D gradient recall echo (GRE) sequences. Its application has presented less motion artifacts, but may miss smaller lesions [18].

Further MR sequences (e.g., ultra-short echo time (UTE) and balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP)) address the challenge resulting from the very short T2* time of the lung parenchyma (1–2 ms at 1.5 T). UTE uses very short echo times, radial sampling of k-space and techniques to increase signals of tissues with very short T2/T2* times (e.g., lung parenchyma, cortical bone) for better visualization. bSSFP uses extremely short repetition times that prevent relaxation of magnetization, generating an almost constant “steady-state” signal, and “balanced” gradients which cause no net dephasing over a repetition time TR [19].

In a recent review, Biederer et al. explored MR data, including UTE and bSSFP, outlining the diagnostic challenges of using MRI for detection, primary or otherwise, of small malignant lesions [20]. The authors discussed potential scenarios in which MRI could play a role moving forward, from no contribution to an adjunct or replacement to CT, depending on further validation of diagnostic quality and cost. They ultimately concluded that while technical feasibility has been achieved, validation of better patient outcomes with MRI are still lacking [20]. Despite these limitations, for lesions near the chest wall, vertebral body, or near the mediastinum, MRI can provide more accurate staging due to its improved soft tissue contrast compared to CT and ability to identify local invasion of adjacent structures, including the mediastinum, ribs, nerve roots, pleura, which provide crucial information for staging [21] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Lung tumor delineation and treatment with MR-guided radiotherapy. A TRUFI sequence obtained on the MRIdian system (Mountain View, CA) for a central non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). MR-guided radiotherapy allows for daily adaptive therapy to decrease dose to nearby organs at risk (Aorta-Yellow; Esophagus-Blue; Spinal Cord-Green) while maintaining dose to the tumor (GTV (Gross Tumor Volume)-Orange). This patient was treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) 60 Gy in 8 fractions and has no evidence of progression of disease at 6 months. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Lastly, other sequences and encoding algorithms may allow for free breathing image acquisition by overcoming image quality sensitivity to motion. In contrast to standard Cartesian k-space acquisition, radial and spiral acquisitions can reduce ghosting and motion artifacts, at the cost of introducing streak artifacts and increasing the acquisition time. Kumar et al. demonstrated that such a sequence (StarVIBE) is feasible with free breathing and intermediate anatomic assessment between compliant breath hold VIBE and noncompliant breath hold VIBE [22]. StarVIBE was also successful in outperforming standard DCE for functional assessments in the setting of motion [22]. Although a full analysis of the utility of whole-body MRI to assess potential metastatic disease is beyond the scope of this review, significant motion artifacts have traditionally limited utility [23]. However, emerging data suggest the technological improvements noted above have improved the viability of whole-body MRI for initial staging [24].

4. Lung functional imaging

Drawing from data in other disease sites, functional MRI sequences are being applied to the lung. One example, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), detects restricted diffusion of water as signal attenuation, enabling hypercellular areas (tumors) to be distinguished from areas of higher diffusivity. In DWI, diffusion is quantified as an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) [25]. In lung cancer, DWI has been shown to more effectively delineate gross tumor volumes within atelectatic lung than CT or PET/CT, a commonly difficult clinical scenario [26]. DWI can also provide additional information over CT, including intratumor vasculature, lymph node involvement, and effusions (Fig. 3). However, DWI may suffer from geometric distortions, mainly induced by susceptibility differences between air and tissue interfaces in the lungs, which may require additional technical solutions [27]. Aside from DWI, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE) also provides functional information in the form of blood flow and vascular permeability, further elucidating patterns of tumor vascularity [28]. This has been successfully investigated in other disease sites, including the prostate (differentiating between malignant tissue and benign hyperplastic tissue) [29] and the brain (differentiating between primary brain malignancies and multiple metastatic histologies) [30], [31]. In the lung, its utility was initially limited by degradation in image quality from respiratory motion [32]. However, within the lung, both the transfer constant derived from DCE-MRI and the apparent diffusion coefficient derived from the intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) DWI model have shown the potential to differentiate lung cancers from solitary pulmonary nodules [33], but this is not currently in clinical use. DCE-MRI has also been compared head-to-head with PET-CT and found to have correlations between the median absolute deviation (MAD) of peak enhancement and standardized uptake value (SUV) for lung cancer [34]. Both DWI and DCE do suffer from suboptimal spatial resolution, especially in the context of respiratory and cardiac motion, although respiratory/cardiac gating and faster temporal acquisition helps mitigate this uncertainty [27], [32].

Fig. 3.

Comparison between CT (a) and diffusion-weighted MR (b) images of the lungs (b-value = 200 smm−2). DWI detected hypointense intratumor vasculature (red arrow) and hyperintense small volume pleural effusion (green arrow), which were not discernible on CT. From the CT images it is unclear if the observed mediastinal lymph node was affected. Nevertheless, its increased signal intensity on DWI (yellow arrow) suggests its involvement. (Adapted from Kaza E. et al. Lung tumor radiotherapy treatment response assessment using Active Breathing Coordinated (ABC) Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Poster presentation at ISMRM 2016.) (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Taking functional imaging one step further, some investigators have combined PET with MRI in an attempt to take the best of both worlds. Unlike PET/CT image acquisition which must be done sequentially, PET/MR can be done simultaneously, improving co-localization of imaging data; combined with improved motion correction algorithms (both for PET correction using simultaneous MR data, and MR correction using other algorithms), PET/MR has the potential to improve detection of small pulmonary nodules and to better delineate regions of disease [35]. In a prospective comparison between PET/CT and PET/MR, the latter successfully staged lung cancer without a statistically significant difference in accuracy from the former [36]. Another prospective study showed equal efficacy in determinations of resectability of lung cancer between PET/CT and PET/MRI [37]. Motion correction algorithms are still dependent on reproducible respiratory motion, which may not be very consistent [35].

Newer developments in MRI technology, including use of hyperpolarized gases and oxygen-enhancement, allow for enhanced contrast and better characterization of function, including regional ventilation, which can reduce radiation toxicity by reducing the volume of functional lung that is being irradiated. Nonetheless, hyperpolarized gases like 129Xe and 3He are quite expensive, the setup is more technically demanding and oxygen-enhanced sequences are both more complex to deliver and come with increased scan times, potentially causing misregistration of images from different points in the respiratory cycle [38]. Further non-contrast enhanced techniques for assessing lung perfusion and ventilation such as arterial spin labeling (ASL) and Fourier decomposition (FD) method can be affected by respiratory motion and low signal [39]. Knowing regional differences in ventilation can aid in radiation planning to avoid dose to relatively high functioning areas in patients with reduced lung function [40].

Aside from pretreatment staging assessments, MRI may also be useful in predicting responses to treatment. In multiple other cancers, DWI has been investigated as an early predictor of tumor response to radiotherapy [41], [42]. In one DWI study in lung cancers > 2 cm, Weller et al demonstrated satisfactory test–retest repeatability and reproducibility of ADC measurements in lung tumor during free breathing and suggest that a change in ADC > 21.9% will reflect treatment-related change [43]. A prospective study by Huang et al. examined patients prior to and after stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) with DCE-MRI/PET and was able to show that changes in MR parameters, including those that are proxies for vascularity and blood flow, can provide early predictions for treatment response [44]. Others have demonstrated the utility of DCE in detecting radiation-induced lung injury [45], while both preclinical [46] and clinical studies [47] using MRI in conjunction with hyperpolarized gases may also help identify this toxicity.

While most data examining the use of MRI in lung cancer diagnosis and treatment response has been retrospective, technical improvements in lung MRI may make this a promising technology for early lung cancer.

5. MRI in radiation treatment

In parallel with the emergence of MRI technologies and techniques for lung imaging, the superior soft tissue contrast and the ability to take advantage of real-time imaging has spurred the integration of MRI into radiation treatment (RT) delivery in the form of devices combining MRI and linear accelerators (MR-linacs). Two main MR-linac commercial systems have emerged: the Elekta MR-linac (Stockholm, Sweden) with a 1.5 T magnet [48] and the ViewRay MRIdian (Oakwood Village, OH) with a 0.35 T magnet [49]. The former was successfully used in prototype form in seven centers [50], [51] and received FDA 510(k) approval in December 2018 with 39 units ordered to date [52]. The latter was FDA-approved in 2017 and is now in use in 18 centers in the United States and around the world [53]. Washington University in St. Louis has reported on their experience utilizing an MR-linac to optimize tumor gating with cine-MRI, particularly important for tumors with significant motion, such as lung cancer [54] (Fig. 4). The same center has used an MR-linac for online adaptive radiotherapy, which allows for the radiation plan to account for day-to-day changes in anatomy and changes in target [55].

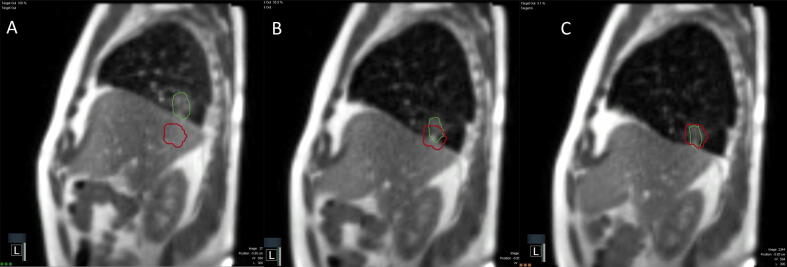

Fig. 4.

MRI CINE and gating for MR-guided stereotactic body radiotherapy. A MRI CINE via the MRIdian System (Mountain View, CA) of a patient undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) to a tumor in the right lower lobe. The CINE runs at 4 frames/second and the tumor (green) is tracked by the MRIdian system. Treatment is not triggered until the tumor moves into the gating structure (red). We typically set the threshold of 95% of the tumor within the gating structure to activate treatment. There may be significant motion of lower lobe tumors when comparing expiration (A) to mid-breath (B) to inspiration (C). We perform the majority of treatments with deep inspiratory breath hold secondary to patient comfort and reproducibility. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The development of the MR-linac is particularly relevant to early stage lung cancer because stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has become a mainstay of therapy for this disease. SBRT involves a high dose per fraction, which may lead to significant normal tissue toxicities and/or higher rates of locoregional recurrence with inappropriate targeting. SBRT for the treatment of early lung cancer requires image-guidance, in the form of cone-beam CT (CBCT), or in the form of kV x-ray on Cyberknife (Accuray, Sunnyvale, California, USA). MR-linac adds an alternative image-guidance modality: MRI. Challenges for MR-guided SBRT include Lorentz forces, MRI geometric distortion, MRI to radiation isocenter uncertainty, multi-leaf collimator (MLC) position error, and uncertainties with voxel size and/or tracking. In the lung, MR-guided SBRT is faced with the additional challenges presented by lung anatomy and physiology (Fig. 1).

Despite these challenges, MR-linac offers advantages to SBRT delivered with most standard linacs including the ability for online adaptive replanning and real-time image guidance. Although this capability is lacking in most standard linacs, technologies like ETHOS (Varian, Palo Alto, California, USA) also allows for similar adaptive replanning. In a simulation study of 10 patients with oligometastatic or primary unresectable disease in the central thorax or non-liver abdomen planned to receive SBRT, MRI-based adaptive planning utilizing anatomy of the day allowed for increased dose in 11 of 15 fractions; in 8 of those fractions, replanning the radiation treatment each day actually decreased dose to organs at risk (esophagus, heart, trachea, brachial plexus, total lung, and spinal cord) [56]. By using the real time visualization and online adaptive capability of MR-guided treatments to maintain planning target volume (PTV) coverage while reducing organ-at-risk (OAR) doses, the MR-linac has the potential to reduce toxicities related to the treatment of early stage lung cancer [57], [58], [59].

Initial data shows promise for use of MR-linac in early stage lung cancer. In a Phase I prospective trial of MR-guided SBRT in the treatment of oligometastatic or unresectable ultracentral thoracic tumors, 5 patients underwent SBRT to a planned dose of 50 Gy in 5 fractions and 10 out of 25 fractions were adapted. Despite not meeting the planned endpoint of feasibility, the investigators were able to improve target coverage over non-adaptive SBRT plans while correcting 100% of OAR constraint violations. No grade 3–5 toxicities occurred within the first 6 months. However, one grade 3 esophageal stricture occurred at 15 months, and one grade 4 pericardial effusion could not be ruled out as possibly related to radiation at 8 months. Lastly, local progression free survival was 100% up to 6 months and 80% at 12 months with an overall survival of 100% up to 6 months and 60% at 12 months [60]. More recent reports have demonstrated the utility of adaptive MRgSBRT for high risk lung tumors, including central lesions, reirradiation, and in patients with interstitial lung disease, resulting in low rates of acute toxicity and promising initial local control [61]. Single fraction MRgSBRT to a total dose of 34 Gy has also been shown to be feasible, with a median delivery time of 39 minutes and a median in-room procedure time of 120 minutes [62].

MR-guided RT is not without challenges. Adding a magnetic field in the setting of radiation treatment creates dosimetric challenges with secondary electrons with an asymmetric penumbra and surface hot spots caused by Lorentz forces [63]. These distortions are increased in the setting of higher magnetic fields, small air cavities, and for tissue-air interfaces (critical for lung), but become less affected by field strength for large air cavities and large fields [64]. Looking specifically at dosimetric effects in the lung, the presence of a longitudinal magnetic field as opposed to a transverse field, radial spread of secondary electrons outside of the photon field were significantly minimized in low density tissues with better dose to the planning target volume (PTV) and better dose homogeneity [65]. Even within a transverse magnetic field up to 1.5 T, these changes in dose distributions can be adequately managed by intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) planning algorithms taking into account the Lorentz forces and have been shown to reduce an initial change of 15% in the max dose (Dmax) down to only 1.6% [66]. In another study of an inline magnetic field, dose enhancement was demonstrated at the target for smaller lesions (up to 23% for at the PTV for gross tumor volumes (GTV) of < 1 cm3), leading to potentially more conformal treatments compared to radiotherapy systems without a magnetic field [67]. In the locally advanced setting, Bainbridge et al. demonstrated a negating of increased skin dose from the Lorentz force by reducing the PTV margin and also were able to isotoxically dose-escalate in the reduced PTV MR-linac-based plan [68]. In a study of lung SBRT patients in a 1.5 T magnetic field, investigators were able to demonstrate an increased skin dose of only 1.4 Gy; with the addition of tumor tracking, they were also able to reduce the mean lung dose by 0.3 Gy without compromising dose to the target [69].

Additional studies have been conducted with Viewray’s previous system with three rotating 60Co sources instead of a linear accelerator (linac), finding similar dosimetry and conformality to traditional linac-based IMRT and VMAT plans. In one comparison to Pinnacle-based IMRT planning, the MRIdian plans demonstrated an average of 4% increase in heterogeneity and differences in conformity of < 1–3% when compared to linac-based plans; the latter also produced better organ at risk (OAR) sparing those with mean doses < 20 Gy, but similar sparing for those with mean doses > 20 Gy [70].

Additional studies have found acceptable results with SBRT planning in addition to conventional planning. When examining SBRT in the lung, Park at al. demonstrated no considerable differences between OAR doses, but some inferiority of 60Co plans when compared to VMAT plans with respect to conformity for PTV volumes < 10 cc, yet still within acceptable levels [71]. Some of the first clinical experiences with MR-guided SBRT have recently been published and indicate appropriate targeting and tracking of tumors that leads to low toxicity and appropriate local control [72]. Wojcieszynski et al. conducted a dosimetric comparison between MRIdian with three 60Co heads and traditional 4D-CT/VMAT plans in 10 patients with early stage NSCLC getting SBRT. No significant differences were found in OAR constraints and target coverage between the two plans, but the MRIdian plans had a lesser conformity index, attributed to the increased penumbrae of the cobalt sources and the larger multi-leaf collimators (MLCs). Despite these shortcomings, all plans were deemed to be clinically acceptable [73].

In addition to the previously discussed soft tissue contrast advantages, both MR-linacs also allow for real time tracking of tumor volumes and normal tissues for bona fide adaptive treatment. Standard linear accelerators utilizing on-board cone beam CT (CBCT) can account for inter-fractional target motion, but not intra-fractional motion. Additionally, unlike MRI, CBCTs involve additional exposure to ionizing radiation to normal tissues not accounted for in the planning process. In two different studies, additional radiation dose has been measured up to 3.5 cGy, 8.3 cGy, and 9.75 cGy for each CBCT [74], [75].

Real-time tumor tracking has been validated in multiple studies. Cerviño et al. demonstrated a mean tracking error of 0.6 mm with free breathing cine-MRI, but their model deteriorated with irregular breathing [76]. More recent studies in tracking have demonstrated more favorable outcomes. Al-Ward et al. were able to reduce mean doses to the heart (3.0 Gy) and lung (1.9 Gy), while lowering the lung V12.5 Gy by 300 cc with 4D MRI tracking when compared to a traditional internal target volume approach (ITV) [77]. In another study of SBRT to lung, pancreas, and adrenal tumors with MR-guided breath-hold and visual feedback, mean GTV geometric areas encompassed during beam-on times was 94–95%, depending on disease site [78]. Overall, the goal is adaptive radiotherapy, in particular dose escalation and isotoxic treatment regimens to optimize tumor control. However, onboard MR images are limited to 2D cine and can only currently track in a single plane at a time. MR images also lack electron density and attenuation coefficient data, unlike CTs, making dose determinations difficult, especially in the lung [79]. To address these issues, studies are ongoing, including one by Wang et al. which evaluated the feasibility of using synthetic CT images from MRI scans for lung cancer radiation treatment planning, demonstrating dose differences<1% for both target coverage and OARs [80]. Despite these challenges, attenuation correction modeling has been improving to enable fully MR-based radiation planning [81].

MR-guided adaptive radiotherapy brings real-time tumor tracking to early stage lung cancer radiotherapy. In addition, due to its improved soft tissue contrast, MRI holds promise for the treatment of ultracentral early lung cancers with MR-guided SBRT.

6. Conclusion

As MRI is making inroads into functional assessment, response to treatment and treatment guidance for a variety of cancers, including brain [82] and prostate [83], MRI use in lung cancer has lagged behind because of inherent barriers arising from the physics of the lung itself. However, with new MR sequences and the application of functional MRI, utility for lung MRI is emerging in the early detection, staging, and surveillance of early stage lung cancer. One major limitation for lung MRI when compared with MDCT remains the detection of subcentimeter nodules. In addition, when applied to radiation treatment, MRI provides excellent soft tissue contrast for tumor and normal tissue delineation and the opportunity for true real-time adaptive therapy. Current data on MR-guided SBRT in early lung cancer are limited, but early results are promising, opening the door for dose escalation, improved normal tissue visualization and normal tissue sparing, improved motion management, and potentially improved outcomes for patients with early stage lung cancer treated with radiotherapy.

7. Funding source

No source of funding was used in this study or in the preparation of this manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Austin J. Sim, Email: austin.sim@moffitt.org.

Evangelia Kaza, Email: ekaza1@bwh.harvard.edu.

Lisa Singer, Email: Lisa_Singer@dfci.harvard.edu.

Stephen A. Rosenberg, Email: Stephen.Rosenberg@moffitt.org.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstraw P., Chansky K., Crowley J. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thoracic Oncol: Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2016;11(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aberle D.R., Adams A.M., Berg C.D. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. New Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker N., Motsch E., Gross M.L. Randomized Study on Early Detection of Lung Cancer with MSCT in Germany: Results of the First 3 Years of Follow-up After Randomization. J Thoracic Oncol: Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2015;10(6):890–896. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.EToloza EM, Harpole L, McCrory DC. Noninvasive staging of non-small cell lung cancer: a review of the current evidence. Chest. 2003 Jan;123 (1 Suppl): 137s-146s. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Murphy G., Haider M., Ghai S. The expanding role of MRI in prostate cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201(6):1229–1238. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wild J.M., Marshall H., Bock M. MRI of the lung (1/3): methods. Insights Imaging. 2012;3(4):345–353. doi: 10.1007/s13244-012-0176-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puderbach M, Hintze C, Ley S, et al. MR imaging of the chest: a practical approach at 1.5T. Eur J Radiol. 2007 Dec;64(3):345–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kaza E., Dunlop A., Panek R. Lung volume reproducibility under ABC control and self-sustained breath-holding. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2017;18(2):154–162. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biederer J., Reuter M., Both M. Analysis of artefacts and detail resolution of lung MRI with breath-hold T1-weighted gradient-echo and T2-weighted fast spin-echo sequences with respiratory triggering. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(2):378–384. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boiselle P.M., Biederer J., Gefter W.B. Expert opinion: why is MRI still an under-utilized modality for evaluating thoracic disorders? J Thorac Imaging. 2013;28(3):137. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31828cafe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller C.J., Loffler R., Deimling M. MR lung imaging at 0.2 T with T1-weighted true FISP: native and oxygen-enhanced. J Magn Resonance Imaging: JMRI. 2001;14(2):164–168. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krempien R.C., Schubert K., Zierhut D. Open low-field magnetic resonance imaging in radiation therapy treatment planning. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(5):1350–1360. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H.S., Lee K.S., Ohno Y. PET/CT versus MRI for diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of lung cancer. J Magn Resonance Imaging: JMRI. 2015;42(2):247–260. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koyama H., Ohno Y., Kono A. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of non-contrast-enhanced pulmonary MR imaging for management of pulmonary nodules in 161 subjects. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(10):2120–2131. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatabu H., Gaa J., Tadamura E. MR imaging of pulmonary parenchyma with a half-Fourier single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE) sequence. Eur J Radiol. 1999;29(2):152–159. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(98)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamashita Y., Yokoyama T., Tomiguchi S. MR imaging of focal lung lesions: elimination of flow and motion artifact by breath-hold ECG-gated and black-blood techniques on T2-weighted turbo SE and STIR sequences. J Magn Resonance Imaging : JMRI. 1999;9(5):691–698. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199905)9:5<691::aid-jmri11>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruegel M., Gaa J., Woertler K. MRI of the lung: value of different turbo spin-echo, single-shot turbo spin-echo, and 3D gradient-echo pulse sequences for the detection of pulmonary metastases. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2007;25(1):73–81. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller G.W., Mugler J.P., 3rd, Sa R.C. Advances in functional and structural imaging of the human lung using proton MRI. NMR Biomed. 2014;27(12):1542–1556. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biederer J., Ohno Y., Hatabu H. Screening for lung cancer: Does MRI have a role? Eur J Radiol. 2017;86:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raptis CA, McWilliams SR, Ratkowski KL, et al. Mediastinal and Pleural MR Imaging: Practical Approach for Daily Practice. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2018 Jan-Feb;38(1):37–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kumar S., Rai R., Stemmer A. Feasibility of free breathing Lung MRI for Radiotherapy using non-Cartesian k-space acquisition schemes. Br J Radiol. 2017;90(1080):20170037. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen G., Lan Y., Zhang K. Comparison of 18F-FDG PET/CT and DWI for detection of mediastinal nodal metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor S.A., Mallett S., Ball S. Diagnostic accuracy of whole-body MRI versus standard imaging pathways for metastatic disease in newly diagnosed non-small-cell lung cancer: the prospective Streamline L trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(6):523–532. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harders S.W., Balyasnikowa S., Fischer B.M. Functional imaging in lung cancer. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2014;34(5):340–355. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X., Fu Z., Gong G. Implementation of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in target delineation of central lung cancer accompanied with atelectasis in precision radiotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(3):2677–2682. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leibfarth S., Winter R.M., Lyng H. Potentials and challenges of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in radiotherapy. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2018;13:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broncano J., Luna A., Sanchez-Gonzalez J. Functional MR Imaging in Chest Malignancies. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2016;24(1):135–155. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren J., Huan Y., Wang H. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic carcinoma: correlation with angiogenesis. Clin Radiol. 2008;63(2):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung B.C., Arevalo-Perez J., Lyo J.K. Comparison of glioblastomas and brain metastases using dynamic contrast-enhanced perfusion MRI. J Neuroimag: Off J Am Soc Neuroimaging. 2016;26(2):240–246. doi: 10.1111/jon.12281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatzoglou V., Tisnado J., Mehta A. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI perfusion for differentiating between melanoma and lung cancer brain metastases. Cancer Med. 2017;6(4):761–767. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin W., Guo J., Rosen M.A. Respiratory motion-compensated radial dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE)-MRI of chest and abdominal lesions. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(5):1135–1146. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan M., Zhang Y.D., Zhu C. Comparison of intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted MR imaging with dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for differentiating lung cancer from benign solitary pulmonary lesions. J Magn Resonance Imaging : JMRI. 2016;43(3):669–679. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S.H., Rimner A., Gelb E. Correlation between tumor metabolism and semiquantitative perfusion magnetic resonance imaging metrics in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boada F.E., Koesters T., Block K.T. Improved detection of small pulmonary nodules through simultaneous MR/PET imaging. PET Clinics. 2018;13(1):89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirchner J., Sawicki L.M., Nensa F. Prospective comparison of (18)F-FDG PET/MRI and (18)F-FDG PET/CT for thoracic staging of non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Messerli M., Barbosa F., Marcon M. Value of PET/MRI for assessing tumor resectability in NSCLC - intra-individual comparison with PET/CT. Br J Radiol. 2018;13:20180379. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20180379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kruger S.J., Nagle S.K., Couch M.J. Functional imaging of the lungs with gas agents. J Magn Resonance Imaging: JMRI. 2016;43(2):295–315. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauman G., Eichinger M. Ventilation and perfusion magnetic resonance imaging of the lung. Polish J Radiol. 2012;77(1):37–46. doi: 10.12659/pjr.882579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai J, McLawhorn R, Altes TA, et al. Helical tomotherapy planning for lung cancer based on ventilation magnetic resonance imaging. Medical Dosimetry: Off J Am Assoc Med Dosimetrists. 2011 Winter;36(4):389–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Pasquier D., Hadj Henni A., Escande A. Diffusion weighted MRI as an early predictor of tumor response to hypofractionated stereotactic boost for prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10407. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28817-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobs L., Intven M., van Lelyveld N. Diffusion-weighted MRI for early prediction of treatment response on preoperative chemoradiotherapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer: a feasibility study. Ann Surg. 2016;263(3):522–528. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weller A., Papoutsaki M.V., Waterton J.C. Diffusion-weighted (DW) MRI in lung cancers: ADC test-retest repeatability. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(11):4552–4562. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-4828-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang Y.S., Chen J.L., Hsu F.M. Response assessment of stereotactic body radiation therapy using dynamic contrast-enhanced integrated MR-PET in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Magn Resonance Imaging: JMRI. 2018;47(1):191–199. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogasawara N., Suga K., Karino Y. Perfusion characteristics of radiation-injured lung on Gd-DTPA-enhanced dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 2002;37(8):448–457. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200208000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zanette B., Stirrat E., Jelveh S. Detection of regional radiation-induced lung injury using hyperpolarized (129)Xe chemical shift imaging in a rat model involving partial lung irradiation: Proof-of-concept demonstration. Advances in radiation oncology. Jul-Sep. 2017;2(3):475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ireland R.H., Din O.S., Swinscoe J.A. Detection of radiation-induced lung injury in non-small cell lung cancer patients using hyperpolarized helium-3 magnetic resonance imaging. Radiother Oncol: J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2010;97(2):244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lagendijk J.J., Raaymakers B.W., van Vulpen M. The magnetic resonance imaging-linac system. Seminars Radiat Oncol. 2014;24(3):207–209. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mutic S., Dempsey J.F. The ViewRay system: magnetic resonance-guided and controlled radiotherapy. Seminars Radiat Oncol. 2014;24(3):196–199. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kerkmeijer L.G., Fuller C.D., Verkooijen H.M. The MRI-linear accelerator consortium: evidence-based clinical introduction of an innovation in radiation oncology connecting researchers, methodology, data collection, quality assurance, and technical development. Front Oncol. 2016;6:215. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raaymakers BW, Jurgenliemk-Schulz IM, Bol GH, et al. First patients treated with a 1.5 T MRI-Linac: clinical proof of concept of a high-precision, high-field MRI guided radiotherapy treatment. Physics in medicine and biology. 2017 Nov 14;62(23):L41-l50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Elekta. Interim report May-January 2018/19 [3/23/19]. Available from: https://www.elekta.com/meta/press-all.html?id=ABA38BC44EA38145.

- 53.ViewRay. MRIdian Locator [12/7/18]. Available from: https://viewray.com/mridian-locator/.

- 54.Fischer-Valuck B.W., Henke L., Green O. Two-and-a-half-year clinical experience with the world's first magnetic resonance image guided radiation therapy system. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2017;2(3):485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henke L.E., Contreras J.A., Green O.L. Magnetic Resonance Image-Guided Radiotherapy (MRIgRT): A 4.5-Year Clinical Experience. Clin Oncol (Royal College of Radiologists (Great Britain)) 2018;30(11):720–727. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henke L., Kashani R., Yang D. Simulated Online Adaptive Magnetic Resonance-Guided Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for the Treatment of Oligometastatic Disease of the Abdomen and Central Thorax: Characterization of Potential Advantages. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(5):1078–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Timmerman R., McGarry R., Yiannoutsos C. Excessive toxicity when treating central tumors in a phase II study of stereotactic body radiation therapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4833–4839. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Timmerman R., Paulus R., Galvin J. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1070–1076. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tekatli H., Haasbeek N., Dahele M. Outcomes of hypofractionated high-dose radiotherapy in poor-risk patients with “ultracentral” non-small cell lung cancer. J Thoracic Oncol: Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2016;11(7):1081–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henke L., Kashani R., Robinson C. Phase I trial of stereotactic MR-guided online adaptive radiation therapy (SMART) for the treatment of oligometastatic or unresectable primary malignancies of the abdomen. Radiother Oncol : J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2018;126(3):519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Finazzi T., Haasbeek C.J.A., Spoelstra F.O.B. Clinical outcomes of stereotactic MR-guided adaptive radiation therapy for high-risk lung tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107(2):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Finazzi T., van Sornsen de Koste J.R., Palacios M.A. Delivery of magnetic resonance-guided single-fraction stereotactic lung radiotherapy. Phys Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2020;14:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.phro.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kirkby C., Stanescu T., Rathee S. Patient dosimetry for hybrid MRI-radiotherapy systems. Med Phys. 2008;35(3):1019–1027. doi: 10.1118/1.2839104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raaijmakers A.J., Raaymakers B.W., Lagendijk J.J. Magnetic-field-induced dose effects in MR-guided radiotherapy systems: dependence on the magnetic field strength. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53(4):909–923. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/4/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kirkby C., Murray B., Rathee S. Lung dosimetry in a linac-MRI radiotherapy unit with a longitudinal magnetic field. Med Phys. 2010;37(9):4722–4732. doi: 10.1118/1.3475942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen X., Prior P., Chen G.P. Technical Note: Dose effects of 1.5 T transverse magnetic field on tissue interfaces in MRI-guided radiotherapy. Med Phys. 2016;43(8):4797. doi: 10.1118/1.4959534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oborn B.M., Ge Y., Hardcastle N. Dose enhancement in radiotherapy of small lung tumors using inline magnetic fields: A Monte Carlo based planning study. Med Phys. 2016;43(1):368. doi: 10.1118/1.4938580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bainbridge H.E., Menten M.J., Fast M.F. Treating locally advanced lung cancer with a 1.5T MR-Linac - Effects of the magnetic field and irradiation geometry on conventionally fractionated and isotoxic dose-escalated radiotherapy. Radiotherapy and oncology. J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2017;125(2):280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Menten M.J., Fast M.F., Nill S. Lung stereotactic body radiotherapy with an MR-linac - Quantifying the impact of the magnetic field and real-time tumor tracking. Radiother Oncol: J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2016;119(3):461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wooten H.O., Green O., Yang M. Quality of Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy Treatment Plans Using a 60Co Magnetic Resonance Image Guidance Radiation Therapy System. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92(4):771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park J.M., Park S.Y., Kim H.J. A comparative planning study for lung SABR between tri-Co-60 magnetic resonance image guided radiation therapy system and volumetric modulated arc therapy. Radiother Oncol : J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2016;120(2):279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosenberg S.A., Henke L.E., Shaverdian N. A multi-institutional experience of MR-Guided liver stereotactic body radiation therapy. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wojcieszynski A.P., Hill P.M., Rosenberg S.A. Dosimetric comparison of real-time MRI-guided tri-cobalt-60 versus linear accelerator-based stereotactic body radiation therapy lung cancer plans. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017;16(3):366–372. doi: 10.1177/1533034617691407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Song W.Y., Kamath S., Ozawa S. A dose comparison study between XVI and OBI CBCT systems. Med Phys. 2008;35(2):480–486. doi: 10.1118/1.2825619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Y., Netherton T., Nitsch P.L. Normal tissue doses from MV image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) using orthogonal MV and MV-CBCT. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2018;19(3):52–57. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cervino L.I., Du J., Jiang S.B. MRI-guided tumor tracking in lung cancer radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56(13):3773–3785. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/13/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Al-Ward S.M., Kim A., McCann C. The development of a 4D treatment planning methodology to simulate the tracking of central lung tumors in an MRI-linac. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2018;19(1):145–155. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Sornsen de Koste JR, Palacios MA, Bruynzeel AME, et al. MR-guided Gated Stereotactic Radiation Therapy Delivery for Lung, Adrenal, and Pancreatic Tumors: A Geometric Analysis. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2018 May 29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Menten MJ, Wetscherek A, Fast MF. MRI-guided lung SBRT: Present and future developments. Physica medica : PM : an international journal devoted to the applications of physics to medicine and biology : official journal of the Italian Association of Biomedical Physics (AIFB). 2017 Dec;44:139-149. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Wang H., Chandarana H., Block K.T. Dosimetric evaluation of synthetic CT for magnetic resonance-only based radiotherapy planning of lung cancer. Radiat Oncol (London, England) 2017;12(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13014-017-0845-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bayisa F.L., Liu X., Garpebring A. Statistical learning in computed tomography image estimation. Med Phys. 2018;45(12):5450–5460. doi: 10.1002/mp.13204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cao Y, Tseng CL, Balter JM, et al. MR-guided radiation therapy: transformative technology and its role in the central nervous system. Neurooncology 2017 Apr 1;19(suppl_2):ii16-ii29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Pathmanathan A.U., van As N.J., Kerkmeijer L.G.W. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided adaptive radiation therapy: a “game changer” for prostate treatment? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100(2):361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]