The outbreak of the 2019 new coronavirus pneumonia has caught worldwide attention. Since December 2019, several pneumonia cases of unknown origin have been found in hospitals in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. The Chinese epidemic prevention authorities have quickly organised laboratories to conduct pathogen tests on alveolar lavage fluid, throat swabs, blood and other samples by methods of virus isolation, nucleic acid testing and genome sequencing, among others. On 7 January 2020, a novel coronavirus, previously undetected in humans, was isolated and its full genome sequence was decoded [1]. On 12 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially named this new coronavirus causing the outbreak of pneumonia in Wuhan the “2019 new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).”

Short abstract

The first case of #COVID19 in Foshan provides a reference for the treatment of severe #SARSCoV2 pneumonia https://bit.ly/3eD81qj

To the Editor:

The outbreak of the 2019 new coronavirus pneumonia has caught worldwide attention. Since December 2019, several pneumonia cases of unknown origin have been found in hospitals in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. The Chinese epidemic prevention authorities have quickly organised laboratories to conduct pathogen tests on alveolar lavage fluid, throat swabs, blood and other samples by methods of virus isolation, nucleic acid testing and genome sequencing, among others. On 7 January 2020, a novel coronavirus, previously undetected in humans, was isolated and its full genome sequence was decoded [1]. On 12 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially named this new coronavirus causing the outbreak of pneumonia in Wuhan the “2019 new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).”

Since the end of December 2019, the number of cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection has increased rapidly. As of 24:00 h on 13 February, there were 63 946 confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 acute respiratory disease in China and 162 confirmed cases in 26 other countries. WHO has classified this outbreak as a public health emergency of international concern. The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 seriously endangers human health and life, affects the social order, and causes substantial economic losses.

Currently, there are no effective drugs for SARS-CoV-2, and its primary treatment is only symptomatic and supportive. Critically ill patients are in danger at any time. Timely measures to prevent the occurrence of severe pneumonia and the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are the key to the treatment of SARS-CoV-2. Although the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 is unclear, its molecular mechanism of infecting human respiratory epithelial cells through the Spike protein is the same as that of SARS-CoV-1 and the symptoms caused by its infection are similar to those of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). At the end of 2002, our hospital had hospitalised and cured the world's first SARS patient, and the total number of these cases admitted and confirmed would surpass 110. No hospitalised patients died and all were eventually discharged. Our hospital has gained meaningful experience in the treatment of severe pneumonia caused by coronavirus infection. To provide a reference for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2, we report the detailed history, onset, disease evolution, diagnosis and treatment of the first case of SARS-CoV-2 in Foshan, China.

This patient was a 40-year-old man with no underlying disease other than hypertension. The patient had no recent travel history to Hubei Province or Wuhan but his wife had recently travelled to Wuhan and returned to Foshan City (Guangdong Province) on 6 January 2020. During her trip, she had a low fever and cough but symptoms were relieved within 1 week without any treatments. The patient went to Guangzhou South railway station, a crowded high-speed rail hub, to pick up his wife. On 10 January 2020, the patient began to get sick, with fever as the initial symptom. There was no discernible pattern of fever, and the highest temperature was 39.0°C, accompanied by chills and intermittent dry cough. However, the patient did not take the disease seriously until ∼1 week later, when his symptoms gradually worsened with shortness of breath, and then he went to the local community hospital for treatment. Test results showed high procalcitonin and hypoxia. The local physicians treated him for bacterial pneumonia but the symptoms did not improve, as he still had a fever, worsened shortness of breath and diarrhoea. Considering that he recently had been in close contact with people from the epidemic area, the local physicians thought he might have SARS-CoV-2. Because his shortness of breath gradually worsened and given the risk of progression to ARDS, he was transferred to our hospital for further treatment.

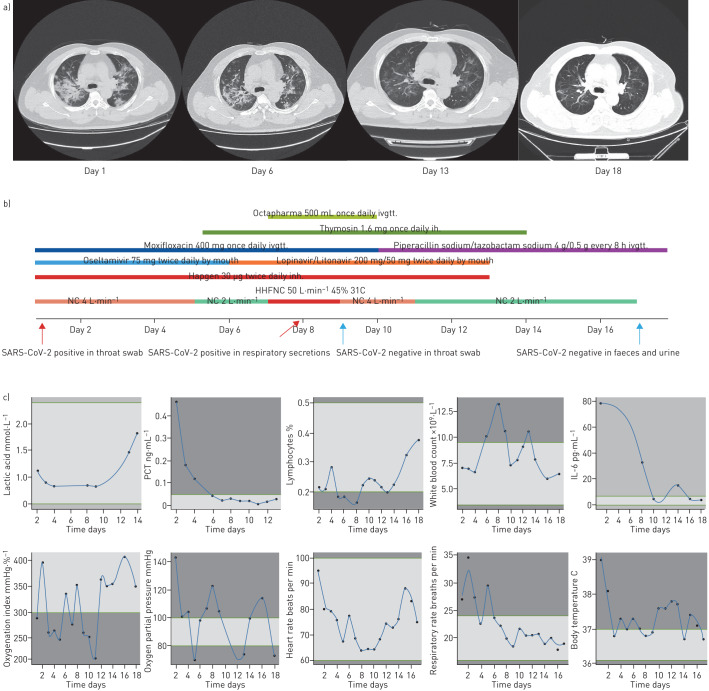

When the patient was admitted to our hospital on 20 January 2020, he was quarantined as a suspected patient, and strict protective measures were taken for his attending doctors and nurses. On that day, he had a chest computed tomography (CT) scan and the result indicated multiple inflammatory exudation in both lungs, mainly interstitial pneumonia (figure 1a). At the same time, a throat swab obtained from the patient was sent to Foshan Centre for Disease Control for the SARS-CoV-2 assay. ∼12 h later, the result was positive for the SARS-CoV-2 sequence detected by RT-PCR assay. The patient was diagnosed as suffering from SARS-CoV-2. The patient had a rapid respiratory rate (>30 breaths per min), respiratory distress and chest CT showed multiple lobar lesions (figure 1a). The patient was in critical condition. On hospital days 1–5, we treated the patient with normal nasal cannula oxygen therapy (4 L·min−1). On days 5 and 6, nasal cannula oxygen therapy was changed to 2 L·min−1. However, on day 7, the patient's oxygenation index decreased to 278 mmHg·%−1, SOFA (Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment) score 2 and CURB-65 score 0. The patient developed acute respiratory failure but did not progress to ARDS. We began to treat him with humidified high-flow nasal cannula (HHFNC) oxygen therapy (31°C, 50 L·min−1, 45% oxygen concentration) for 48 h. The patient's symptoms were beginning to relieve by day 9, and we continued ordinary nasal cannula oxygen therapy at 4 L·min−1 on days 9–14 and 2 L·min−1 on days 14–17. The antivirus therapy was as follow: oseltamivir was administered orally at 75 mg twice daily from day 1 to day 6; lopinavir/litonavir orally at 200 mg/50 mg twice daily from day 7 to day 13; and hapgen atomised 30 µg every 12 h from day 1 to day 14. To enhance immunity, the patient was hypodermically injected with thymosin 1.6 mg once daily from day 3 to day 14. To prevent bacterial infection, the patient was given moxifloxacin intravenous drip 400 mg once daily from day 1 to 10 and piperacillin sodium/tazobactam sodium (8/1) 4.5 g every 8 h ivgtt from day 11 to day 18. From day 7 to day 10, the patient was given 20% human serum albumin (Octapharma) intravenous drip 50 mL once daily. Full drugs, therapies and RT-PCR test results were shown in figure 1b. During the treatment, blood gas analysis, liver function, inflammation indicators, blood routine indicators and other parameters were checked regularly (figure 1c). On day 9, the result of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test from his throat swab sample was negative and the two subsequent tests on day 17 were also negative for SARS-CoV-2 from patient's faeces and urine. At the same time, his fever and shortness of breath were significantly relieved, and his oxygenation improved. Oxygen therapy was no longer required, and the patient was declared clinically cured and discharged from hospital in day 18 (6 February 2020). Glucocorticoids were not used throughout the treatment.

FIGURE 1.

Treatments and test results. a) Computed tomography results on days 1, 6, 13 and 18. b) Drug treatments and RT-PCR test results along. c) Patient status tracking during treatment, including lactic acid level, procalcitonin (PCT) level, lymphocyte percentage value, white blood cell count, interleukin (IL)-6 level, oxygenation index level, oxygen partial pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and body temperature. Green lines represent the limits of normal values and light shading represents the normal range. HHNFC: humidified high-flow nasal cannula; NC: nasal cannula; ivgtt: intravenous glucose drip; ih: hypodermic injection; inh inhalation.

The infection source of the patient deserves our attention. Before the illness onset, the patient had no travel history to the epidemic area (Wuhan) with community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and had no contact with confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection. His illness began after he went to a high-speed train station to pick up his wife, who had returned from the epidemic area of Wuhan. His wife developed a low fever cough on 4 January and her body temperature decreased to normal values after returning to Foshan. She was also admitted to the hospital for isolation on 2 January; the result of chest examination was normal and the results of two throat swabs (which were obtained at an interval of 24 h) tested for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid by RT-PCR assays were both negative. Although the patient's wife cannot be ruled out as the direct source of infection, the infection source may have also come from other SARS-CoV-2 carriers from the epidemic area of Wuhan in the crowded high-speed railway station. In conclusion, this patient is a typical case of human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Other relatives who had close contact with the patient were not infected during the isolation period. The patient is the earliest confirmed case of human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection outside the epidemic area in China. When the patient was diagnosed, the provinces and cities in China also rapidly started implementing major public health measures to prevent further spread of SARS-CoV-2.

The patient had multiple organ damage and the main target organ was the lung. After 14 days of the course of the disease, there were still changes in the pulmonary imaging progress when the respiratory nucleic acid had begun to turn negative, and the other organs had also recovered from the damage. The pulmonary imaging progress might be related to the incomplete clearance of the virus. The nucleic acid of respiratory secretions, in this case, turned negative around the 16th day of the course of the disease, which was accompanied by the improvement of pulmonary imaging. The clinical symptoms of the disease were not consistent with the imaging changes but more consistent with the respiratory nucleic acid conversion to negative. According to the disease development of this patient, the natural course of the severe case was as long as 18 days and the disease did not enter the progressive stage until 1 week after the onset of the disease.

The patient's body temperature returned to normal before the use of lopinavir and ritonavir tablets but the respiratory secretions still tested positive for the nucleic acid RT-PCR test 2 days after the use of lopinavir and ritonavir tablets. The dynamics of the recovery of the lung and other organ damage probably reflected the natural progression taking into account the point at which the respiratory nucleic acid tests began to turn negative. Therefore, there is no evidence that patients respond well to treatment, and there is no apparent advantage in the antiviral clinical effect of lopinavir and ritonavir tablets.

On day 7 after the onset of the disease, the patient started to have acute respiratory failure, which lasted for ∼1 week. However, after HHFNC oxygen therapy, intermittent noninvasive ventilation and other supportive treatment, the condition of the patient gradually stabilised, and thus invasive mechanical ventilation therapy was avoided. Studies have shown that HHFNC oxygen therapy can reduce the intubation rate of patients with acute respiratory failure, which can not only improve the symptoms of hypoxia and avoid carbon dioxide retention but also provide some positive end-expiratory pressure to avoid atelectasis [2]. When the patients have obvious shortness of breath that cannot be alleviated by ordinary oxygen therapy, active and full respiratory support should be applied. HHFNC oxygen may be the most valuable for lung protection and recovery. Meanwhile, active atomisation treatment may also be beneficial in improving the condition, which has been reported in Germany for SARS-CoV-2 [3]. In this case of pneumonia, the characteristics of lung lesions were different from ARDS caused by traditional community-acquired pneumonia and the tissue functions of noninvolved lung were basically normal, so there were mild symptoms and serious lung imaging changes [4].

Notably, regarding the blood analysis, SARS-CoV-2 is mainly characterised by low numbers of both white blood cells and lymphocytes. Thymosin a1-a, as a widely used immunomodulatory agent, was given to the patient to enhance his immunity during the treatment [5]. After injection, the number of lymphocytes and the lymphocyte percentage of the patient returned to normal, and no drug-related fever or allergic reactions were detected. After this treatment, the serum interleukin (IL)-6 of the patient decreased gradually and his clinical symptoms were relieved, which was consistent with the nature of ARDS, an acute inflammatory clinical syndrome per se [6]. The patient's leukocyte count was low and IL-6 was high at the early stage, but his overall serum inflammatory level was less severe than those of patients with bacterial sepsis or ARDS.

The pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 is unknown but its molecular mechanism for infecting human respiratory epithelial cells through Spike protein is the same as that of SARS-CoV-1 and the infection symptoms are similar to those of SARS. The overall mortality of SARS was ∼11%, whereas the mortality of SARS-CoV-2 is ∼2%. However, the total number of SARS-CoV-2 cases has exceeded that of the entire SARS crisis. In comparison with SARS-CoV-1, the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 has increased but the virulence has weakened. The reason why SARS-CoV-2 caused the severe epidemic is directly related to the large number of patients with mild illness. Because it is a new coronavirus, people unconsciously compared it with SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV, and thus felt “deceived” and panicked. The recovery of this patient with severe pneumonia is relatively close to a natural outcome and the antiviral drugs may be ineffective. The characteristics of pulmonary lesions caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection are different from ARDS caused by traditional acquired pneumonia. The normal lung tissues could provide fine functional compensation, resulting in mild symptoms and serious pulmonary imaging changes, which should be taken seriously in following a coping strategy.

SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted among human beings. Compared with SARS-CoV-1, its infectivity is higher but its virulence is weaker; hence, its response to conventional treatment may be relatively better. There may be a latent transmission of SARS-CoV-1 and people without any symptoms can also transmit the virus. Timely and sufficient noninvasive respiratory support and atomisation are effective to mitigate the respiratory distress. Immunomodulatory drugs can be applied appropriately in the absence of excessive inflammation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: L. Zhou has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: W. Wen has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H. Bai has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: F. Wang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H. Yan has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Li has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Liang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Zhong has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Shao has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T. Yu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Qiang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Mao has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Z. Guan has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Ye has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: W. Luo has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu Z, Li Y, Zhou J, et al. High-flow nasal cannula in adults with acute respiratory failure and after extubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res 2018; 19: 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 970–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, et al. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Radiology 2020; 295: 202–207. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang FY, Fang B, Qiang XH, et al. The efficacy and immunomodulatory effects of ulinastatin and thymosin α1 for sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 9508493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012; 307: 2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]